Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

RCBC vs. Ca

Enviado por

Jhenjhen GandaDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

RCBC vs. Ca

Enviado por

Jhenjhen GandaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

FIRST DIVISION

its account representative, all remaining checks outstanding as of the

date the account was forwarded were no longer presented for payment.

[G.R. No. 133107. March 25, 1999.]

RIZAL COMMERCIAL BANKING CORPORATION, Petitioner, v.

COURT OF APPEALS and FELIPE LUSTRE, Respondents.

DECISION

KAPUNAN, J.:

A simple telephone call and an ounce of good faith on the part of

petitioner could have prevented, the present controversy.

On March 10, 1993, private respondent Atty. Felipe Lustre purchased a

Toyota Corolla from Toyota Shaw, Inc. for which he made a down payment

of P164,620.00, the balance of the purchase price to be paid in 24 equal

monthly installments. Private respondent thus issued 24 postdated

checks for the amount of P14,976.00 each. The first was dated April 10,

1991; subsequent checks were dated every 10th day of each succeeding

month.

To secure the balance, private respondent executed a promissory note 1

and a contract of chattel mortgage 2 over the vehicle in favor of Toyota

Shaw, Inc. The contract of chattel mortgage, in paragraph 11 thereof,

provided for an acceleration clause stating that should the mortgagor

default in the payment of any installment, the whole amount remaining

unpaid shall become due. In addition, the mortgagor shall be liable for

25% of the principal due as liquidated damages.

On March 14, 1991, Toyota Shaw, Inc. assigned all its rights and interests

in the chattel mortgage to petitioner Rizal Commercial Banking

Corporation (RCBC).

All the checks dated April 10, 1991 to January 10, 1993 were thereafter

encashed and debited by RCBC from private respondents account,

except for RCBC Check No. 279805 representing the payment for August

10, 1991, which was unsigned. Previously, the amount represented by

RCBC Check No. 279805 was debited from private respondents account

but was later recalled and re-credited to him. Because of the recall, the

last two checks, dated February 10, 1993 and March 10, 1993, were no

longer presented for payment. This was purportedly in conformity with

petitioner banks procedure that once a clients account was forwarded to

On the theory that respondent defaulted in his payments, the check

representing the payment for August 10, 1991 being unsigned,

Petitioner, in a letter dated January 21, 1993, demanded from private

respondent the payment of the balance of the debt, including liquidated

damages. The latter refused, prompting petitioner to file an action for

replevin and damages before the Pasay City Regional Trial Court (RTC).

Private respondent, in his Answer, interposed a counterclaim for

damages.

After trial, the RTC 3 rendered a decision disposing of the case as

follows:chanrob1es virtual 1aw library

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, judgment is hereby rendered as

follows:chanrob1es virtual 1aw library

I. The complaint, for lack of cause of action, is hereby DISMISSED and

plaintiff RCBC is hereby ordered,

A. To accept the payment equivalent to the three checks amounting to a

total of P44,938.00, without interest

B. To release/cancel the mortgage on the car . . . upon payment of the

amount of P44,938.00 without interest.

C. To pay the cost of suit

II. On The Counterclaim

A. Plaintiff RCBC to pay Atty. Lustre the amount of P200,000.00 as moral

damages.

B. RCBC to pay P100,000.00 as exemplary damages.

C. RCBC to pay Atty. Obispo P50,000.00 as Attorneys fees. Atty. Lustre is

not entitled to any fee for lawyering for himself.

All awards for damages are subject to payment of fees to be assessed by

the Clerk of Court, RTC, Pasay City.

SO ORDERED.

On appeal by petitioner, the Court of Appeals affirmed the decision of the

RTC, thus:chanrob1es virtual 1aw library

We . . . concur with the trial courts ruling that the Chattel Mortgage

contract being a contract of adhesion that is, one wherein a party,

usually a corporation, prepares the stipulations in the contract, while the

other party merely affixes his signature or his "adhesion" thereto . . . is

to be strictly construed against appellant bank which prepared the form

Contract . . . Hence . . . paragraph 11 of the Chattel Mortgage contract

[containing the acceleration clause] should be construed to cover only

deliberate and advertent failure on the part of the mortgagor to pay an

amortization as it became due in line with the consistent holding of the

Supreme Court construing obscurities and ambiguities in the restrictive

sense against the drafter thereof . . . in the light of Article 1377 of the

Civil Code.

In the case at bench, plaintiff-appellants imputation of default to

defendant-appellee rested solely on the fact that the 5th check issued by

appellee . . . was recalled for lack of signature. However, the check was

recalled only after the amount covered thereby had been deducted from

defendant-appellees account, as shown by the testimony of plaintiffs

own witness Francisco Bulatao who was in charge of the preparation of

the list and trial balances of bank customers . . . . The "default" was

therefore not a case of failure to pay, the check being sufficiently funded,

and which amount was in fact already debitted [sic] from appellees

account by the appellant bank which subsequently re-credited the

amount to defendant-appellees account for lack of signature. All these

actions RCBC did on its own without notifying defendant until sixteen (16)

months later when it wrote its demand letter dated January 21, 1993.

Clearly, appellant bank was remiss in the performance of its functions for

it could have easily called the defendants attention to the lack of

signature on the check and sent the check to, or summoned, the latter to

affix his signature. It is also to be noted that the demand letter contains

no explanation as to how defendant-appellee incurred arrearages in the

amount of P66,255.70, which is why defendant-appellee made a protest

notation thereon.

Notably, all the other checks issued by the appellee dated subsequent to

August 10, 1991 and dated earlier than the demand letter, were duly

encashed. This fact should have already prompted the appellant bank to

review its action relative to the unsigned check. . . 4

We take exception to the application by both the trial and appellate

courts of Article 1377 of the Civil Code, which states:chanrob1es virtual

1aw library

The interpretation of obscure words or stipulations in a contract shall not

favor the party who caused the obscurity.

It bears stressing that a contract of adhesion is just as binding as

ordinary contracts. 5 It is true that we have, on occasion, struck down

such contracts as void when the weaker party is imposed upon in dealing

with the dominant bargaining party and is reduced to the alternative of

taking it or leaving it, completely deprived of the opportunity to bargain

on equal footing. 6 Nevertheless, contracts of adhesion are not invalid

per se; 7 they are not entirely prohibited. 8 The one who adheres to the

contract is in reality free to reject it entirely; if he adheres, he gives his

consent. 9

While ambiguities in a contract of adhesion are to be construed against

the party that prepared the same, 10 this rule applies only if the

stipulations in such contract are obscure or ambiguous. If the terms

thereof are clear and leave no doubt upon the intention of the

contracting parties, the literal meaning of its stipulations shall control. 11

In the latter case, there would be no need for construction. 12

Here, the terms of paragraph 11 of the Chattel Mortgage Contract 13 are

clear. Said paragraph states:chanrob1es virtual 1aw library

11. In case the MORTGAGOR fails to pay any of the installments, or to pay

the interest that may be due as provided in the said promissory note, the

whole amount remaining unpaid therein shall immediately become due

and payable and the mortgage on the property (ies) herein-above

described may be foreclosed by the MORTGAGEE, or the MORTGAGEE

may take any other legal action to enforce collection of the obligation

hereby secured, and in either case the MORTGAGOR further agrees to

pay the MORTGAGEE an additional sum of 25% of the principal due and

unpaid, as liquidated damages, which said sum shall become part

thereof. The MORTGAGOR hereby waives reimbursement of the amount

heretofore paid by him/it to the MORTGAGEE.

The above terms leave no room for construction. All that is required is the

application thereof.

Petitioner claims that private respondents check representing the fifth

installment was "not encashed," 14 such that the installment for August

1991 was not paid. By virtue of paragraph 11 above, petitioner submits

that it "was justified in treating the entire balance of the obligation as

due and demandable." 15 Despite demand by petitioner, however,

private respondent refused to pay the balance of the debt. Petitioner, in

sum, imputes delay on the part of private Respondent.

We do not subscribe to petitioners theory.

Article 1170 of the Civil Code states that those who in the performance of

their obligations are guilty of delay are liable for damages. The delay in

the performance of the obligation, however, must be either malicious or

negligent. 16 Thus, assuming that private respondent was guilty of delay

in the payment of the value of the unsigned check, private respondent

cannot be held liable for damages. There is no imputation, much less

evidence, that private respondent acted with malice or negligence in

failing to sign the check. Indeed, we agree with the Court of Appeals

finding that such omission was mere "inadvertence" on the part of

private Respondent. Toyota salesperson Jorge Geronimo testified that he

even verified whether private respondent had signed all the checks and

in fact returned three or four unsigned checks to him for

signing:chanrob1es virtual 1aw library

Atty. Obispo:chanrob1es virtual 1aw library

After these receipts were issued, what else did you do about the

transaction?

A: During our transaction with Atty. Lustre, I found out when he issued to

me the 24 checks, I found out 3 to 4 checks are assigned and I asked him

to sign these checks.

Atty. Obispo:chanrob1es virtual 1aw library

What did you do?

A: I asked him to sign the checks. After signing the checks, I reviewed

again all the documents, after I reviewed all the documents and found

out that all are completed and the downpayments was completed, we

released to him the car. 17

Even when the checks were delivered to petitioner, it did not object to

the unsigned check. In view of the lack of malice or negligence on the

part of private respondent, petitioners blind and mechanical invocation

of paragraph 11 of the contract of chattel mortgage was unwarranted.

Petitioners conduct, in the light of the circumstances of this case, can

only be described as mercenary. Petitioner had already debited the value

of the unsigned check from private respondents account only to re-credit

it much later to him. Thereafter, petitioner encashed checks

subsequently dated, then abruptly refused to encash the last two. More

than a year after the date of the unsigned check, Petitioner, claiming

delay and invoking paragraph 11, demanded from private respondent

payment of the value of said check and that of the last two checks,

including liquidated damages. As pointed out by the trial court, this

whole controversy could have been avoided if only petitioner bothered to

call up private respondent and ask him to sign the check. Good faith not

only in compliance with its contractual obligations, 18 but also in

observance of the standard in human relations, for every person "to act

with justice, give everyone his due, and observe honesty and good faith,"

19 behooved the bank to do so.chanroblesvirtuallawlibrary

Failing thus, petitioner is liable for damages caused to private

Respondent. 20 These include moral damages for the mental anguish,

serious anxiety, besmirched reputation, wounded feelings and social

humiliation suffered by the latter. 21 The trial court found that private

respondent was

[a] client who has shared transactions for over twenty years with a bank .

. . The shabby treatment given the defendant is unpardonable since he

was put to shame and embarrassment after the case was filed in Court.

He is a lawyer in his own right, married to another member of the bar. He

sired children who are all professionals in their chosen field. He is known

to the community of golfers with whom he gravitates. Surely, the filing of

the case made defendant feel bad and bothered.

To deter others from emulating petitioners callous example, we affirm

the award of exemplary damages. 22 As exemplary damages are

warranted, so are attorneys fees. 23

We, however, find excessive the amount of damages awarded by the trial

court in favor of private respondent with respect to his counterclaims

and, accordingly, reduce the same as follows:chanrob1es virtual 1aw

library

(a) Moral damages from P200,000.00 to P100,000.00,

(b) Exemplary damages from P100,000.00 to P75,000.00,

(c) Attorneys fees from P50,000.00 to P30,000.00.

WHEREFORE, subject to these modifications, the decision of the Court of

Appeals is AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

Davide, Jr., C.J., Melo and Pardo, JJ., concur.

RCBC VS. CA

G.R. No. 133107 March 25, 1999

FACTS: Private respondent Atty. Felipe Lustre purchased a Toyota Corolla

from Toyota Shaw, Inc. He made a down payment of P164,620.00. He

issued 24 postdated checks amounting to P14,976.00 each in order to

pay the remaining balance of the purchase.

To secure the balance, private respondent executed a promissory note

and a contract of chattel mortgage over the vehicle in favor of Toyota

Shaw, Inc. which provided for an acceleration clause. It was stipulated

that should the mortgagor default in the payment of any installment, the

whole amount remaining unpaid shall become due. In addition, the

mortgagor shall be liable for 25% of the principal due as liquidated

damages.

The checks were encashed and debited by RCBC from private

respondents account, except for RCBC Check No. 279805 representing

the payment for August 10, 1991, which was unsigned. Previously, the

amount represented by RCBC Check No. 279805 was debited from

private respondents account but was later recalled and re-credited to

him. Because of the recall, the last two checks, dated February 10, 1993

and March 10, 1993, were no longer presented for payment. This was

purportedly in conformity with petitioner banks procedure that once a

clients account was forwarded to its account representative, all

remaining checks outstanding as of the date the account was forwarded

were no longer presented for payment.

On the theory that respondent defaulted in his payments, the check

representing the payment for August 10, 1991 being unsigned,

petitioner, in a letter dated January 21, 1993, demanded from private

respondent the payment of the balance of the debt, including liquidated

damages. The latter refused.

Issue: Whether or not the private respondents refusal to pay the

balance of the debt constitute delay on his part.

Ruling: No. Article 1170 of the Civil Code states that those who in the

performance of their obligations are guilty of delay are liable for

damages. The delay in the performance of the obligation, however, must

be either malicious or negligent. Thus, assuming that private respondent

was guilty of delay in the payment of the value of the unsigned check,

private respondent cannot be held liable for damages. There is no

imputation, much less evidence, that private respondent acted with

malice or negligence in failing to sign the check. The omission was mere

inadvertence on the part of private respondent.

Você também pode gostar

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionNo EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Dishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintNo EverandDishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- RCBC V CADocumento6 páginasRCBC V CAAra Lorrea MarquezAinda não há avaliações

- RCBC Vs CADocumento6 páginasRCBC Vs CAhernan paladAinda não há avaliações

- RCBC v. CaDocumento2 páginasRCBC v. CaRAINBOW AVALANCHEAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 133107 March 25, 1999 Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation, Petitioner, COURT OF APPEALS and FELIPE LUSTRE, RespondentsDocumento50 páginasG.R. No. 133107 March 25, 1999 Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation, Petitioner, COURT OF APPEALS and FELIPE LUSTRE, RespondentsRomel MedenillaAinda não há avaliações

- Oblicon Quiz2Documento71 páginasOblicon Quiz2Dawn JessaAinda não há avaliações

- Rizal BankingDocumento3 páginasRizal BankingMariaAinda não há avaliações

- Oblicon Quiz2Documento93 páginasOblicon Quiz2Dawn Jessa GoAinda não há avaliações

- 5-Rizal Commercial Banking Corp. vs. CA.Documento9 páginas5-Rizal Commercial Banking Corp. vs. CA.Angelie FloresAinda não há avaliações

- RIZAL COMMERCIAL BANKING CORPORATION, Petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and FELIPE LUSTREDocumento5 páginasRIZAL COMMERCIAL BANKING CORPORATION, Petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and FELIPE LUSTREMarlon DizonAinda não há avaliações

- RCBC vs. Ca Kapunan, J. - G.R. No. 133107 - March 25, 1999 FactsDocumento2 páginasRCBC vs. Ca Kapunan, J. - G.R. No. 133107 - March 25, 1999 FactsMark Hiro NakagawaAinda não há avaliações

- RCBC vs. CADocumento2 páginasRCBC vs. CAFairyssa Bianca SagotAinda não há avaliações

- RCBC Vs CADocumento4 páginasRCBC Vs CALeizl A. VillapandoAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 133107 - RCBC v. Court of AppealsDocumento8 páginasG.R. No. 133107 - RCBC v. Court of AppealsCharlotte GalineaAinda não há avaliações

- RCBC V CADocumento2 páginasRCBC V CAhmn_scribdAinda não há avaliações

- Facts: Private Respondent Atty. Felipe Lustre Purchased A Toyota Corolla FromDocumento2 páginasFacts: Private Respondent Atty. Felipe Lustre Purchased A Toyota Corolla FromJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Oblicon MidtermsDocumento73 páginasOblicon MidtermsErianne DuAinda não há avaliações

- 30-Villanueva vs. Nite 496 SCRA 549 (2006)Documento4 páginas30-Villanueva vs. Nite 496 SCRA 549 (2006)Ronald Alasa-as AtigAinda não há avaliações

- Oblicon Articles 1231-1250Documento52 páginasOblicon Articles 1231-1250luismisaAinda não há avaliações

- Oblicon Articles 1231-1250Documento52 páginasOblicon Articles 1231-1250luismisaAinda não há avaliações

- Payment Spouses Deo Agner and Maricon Agner, Petitioners, Bpi Family Savings Bank, Inc., RespondentDocumento41 páginasPayment Spouses Deo Agner and Maricon Agner, Petitioners, Bpi Family Savings Bank, Inc., RespondentMarry SuanAinda não há avaliações

- 2017 Case Digests - Mercantile LawDocumento84 páginas2017 Case Digests - Mercantile LawedreaAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Marquez v. Elisan Credit Corp.Documento14 páginas2 Marquez v. Elisan Credit Corp.Sarah C.Ainda não há avaliações

- Buenaventura Vs MetropolitanDocumento40 páginasBuenaventura Vs MetropolitanMadz Rj MangorobongAinda não há avaliações

- Article 1370 Civil Code JurisprudenceDocumento16 páginasArticle 1370 Civil Code JurisprudenceKatherine OlidanAinda não há avaliações

- Oblicon Chapter2 DigestDocumento57 páginasOblicon Chapter2 DigestEzekiel Japhet Cedillo EsguerraAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 161865Documento8 páginasG.R. No. 161865Maine FloresAinda não há avaliações

- 2 - Magdalena Estates Inc Vs RodriguezDocumento3 páginas2 - Magdalena Estates Inc Vs RodriguezLariza Aidie100% (1)

- Deed of AssgnmentDocumento15 páginasDeed of Assgnmentjasmin torionAinda não há avaliações

- Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Felipe Lustre, Respondents. G.R. No. 133107, March 25, 1999Documento2 páginasRizal Commercial Banking Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Felipe Lustre, Respondents. G.R. No. 133107, March 25, 1999hmn_scribdAinda não há avaliações

- ROMAN CATHOLIC BISHOP OF MALOLOS, INC., Petitioner, v. INTERMEDIATE APPELLATE COURT, and ROBES-FRANCISCO REALTY AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, Respondents.Documento9 páginasROMAN CATHOLIC BISHOP OF MALOLOS, INC., Petitioner, v. INTERMEDIATE APPELLATE COURT, and ROBES-FRANCISCO REALTY AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, Respondents.Ro CheAinda não há avaliações

- Second Div Tan Vs CA 2001Documento8 páginasSecond Div Tan Vs CA 2001Jan Veah CaabayAinda não há avaliações

- Negotiable Instruments Law CasesDocumento4 páginasNegotiable Instruments Law CasesElineth AguilarAinda não há avaliações

- Lo vs. KJS Eco-Formwork System Phil., Inc., G.R. No. 149420, 08 Oct 2003Documento4 páginasLo vs. KJS Eco-Formwork System Phil., Inc., G.R. No. 149420, 08 Oct 2003info.ronspmAinda não há avaliações

- 171577-2015-Marquez v. Elisan Credit Corp PDFDocumento14 páginas171577-2015-Marquez v. Elisan Credit Corp PDFMonicaSumangaAinda não há avaliações

- SEC 25 Full CaseDocumento189 páginasSEC 25 Full CaseKhristine ArellanoAinda não há avaliações

- 3rd Case DigestDocumento3 páginas3rd Case DigestNoela Glaze Abanilla DivinoAinda não há avaliações

- Republic V PNB - Fncbny, G.R. No. L-16106, December 30, 1961Documento2 páginasRepublic V PNB - Fncbny, G.R. No. L-16106, December 30, 1961Jona Myka DugayoAinda não há avaliações

- MANILA-BANKING-V-TEODORO DigestDocumento4 páginasMANILA-BANKING-V-TEODORO DigestLau NunezAinda não há avaliações

- SONNY LO v. KJS ECO-FORMWORK SYSTEM (OBLI)Documento5 páginasSONNY LO v. KJS ECO-FORMWORK SYSTEM (OBLI)SOEDIV OKAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 158635 December 9, 2005 Magna Financial Services Group, Inc., Petitioner, ELIAS COLARINA, RespondentDocumento4 páginasG.R. No. 158635 December 9, 2005 Magna Financial Services Group, Inc., Petitioner, ELIAS COLARINA, RespondentBibi JumpolAinda não há avaliações

- Spouses Agner V BPI, G.R. No. 182963, June 3, 2013Documento3 páginasSpouses Agner V BPI, G.R. No. 182963, June 3, 2013Lyle BucolAinda não há avaliações

- Obli Con - Article 1169Documento23 páginasObli Con - Article 1169Manilyn Beronia Pascioles0% (1)

- LBP Vs Monet's Export & MFG Corp 161865 J. Ynares-Santiago First Division DecisionDocumento9 páginasLBP Vs Monet's Export & MFG Corp 161865 J. Ynares-Santiago First Division DecisionjonbelzaAinda não há avaliações

- Oh vs. Court of Appeals, 403 SCRA 300Documento11 páginasOh vs. Court of Appeals, 403 SCRA 300Chanyeol ParkAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 194642 - Marquez vs. Elisan Credit CorpDocumento17 páginasG.R. No. 194642 - Marquez vs. Elisan Credit Corpstudybuds2023Ainda não há avaliações

- Supreme CourtDocumento6 páginasSupreme CourtRyannCabañeroAinda não há avaliações

- Republic of The Philippines Supreme Court Manila Third DivisionDocumento22 páginasRepublic of The Philippines Supreme Court Manila Third DivisionJelina MagsuciAinda não há avaliações

- Notice: Republic of The Philippines Supreme CourtDocumento5 páginasNotice: Republic of The Philippines Supreme CourtAllanis Rellik PalamianoAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 157309 Velasquez Vs SolidBankDocumento9 páginasG.R. No. 157309 Velasquez Vs SolidBankJessie AncogAinda não há avaliações

- Landl and Co Vs MetrobankDocumento10 páginasLandl and Co Vs MetrobankJephraimBaguyoAinda não há avaliações

- DigestDocumento105 páginasDigestJohn Robert BautistaAinda não há avaliações

- Ynares-Santiago, J.Documento9 páginasYnares-Santiago, J.Anida DomiangcaAinda não há avaliações

- SALES and LEASE5 - GR NO 214752 - Equitable Savings Bank V PalcesDocumento3 páginasSALES and LEASE5 - GR NO 214752 - Equitable Savings Bank V PalcesMacky CaballesAinda não há avaliações

- Fernandez Law Office and Millar and Esguerra For Petitioner. Francisco de La Fuente For RespondentsDocumento4 páginasFernandez Law Office and Millar and Esguerra For Petitioner. Francisco de La Fuente For RespondentsVeraNataaAinda não há avaliações

- Metrobank Vs CA 1999Documento2 páginasMetrobank Vs CA 1999Al DrinAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 93176Documento5 páginasG.R. No. 93176Demi Lynn YapAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digest - ROMAN CATHOLIC BISHOP OF MALOLOS Vs IACDocumento4 páginasCase Digest - ROMAN CATHOLIC BISHOP OF MALOLOS Vs IACMaricris GalingganaAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsNo EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- RCBC vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 133107, March 25, 1999 305 SCRA 449Documento1 páginaRCBC vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 133107, March 25, 1999 305 SCRA 449Jhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Dr. Fernando Periquet, Jr. vs. The Court of Appeals G.R. No. L-69996 DECEMBER 5, 1994Documento1 páginaDr. Fernando Periquet, Jr. vs. The Court of Appeals G.R. No. L-69996 DECEMBER 5, 1994Jhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Racquel-Santos V. Ca G.R. No. 174986 July 7, 2009Documento2 páginasRacquel-Santos V. Ca G.R. No. 174986 July 7, 2009Jhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- State Investment House Inc. vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 115548 MARCH 5, 1996Documento1 páginaState Investment House Inc. vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 115548 MARCH 5, 1996Jhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Tayag vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 96053 MARCH 3, 1993Documento1 páginaTayag vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 96053 MARCH 3, 1993Jhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- DecisionDocumento1 páginaDecisionJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Jacinto Tanguilig vs. Court of Appeals and Vicente Herce Jr. G.R. No. 117190 JANUARY 2, 1997Documento1 páginaJacinto Tanguilig vs. Court of Appeals and Vicente Herce Jr. G.R. No. 117190 JANUARY 2, 1997Jhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Teknolohiya para Sa Mamamayan (AGHAM) and Sining Maria RosaDocumento2 páginasTeknolohiya para Sa Mamamayan (AGHAM) and Sining Maria RosaJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Commission, We Said That: "Salary" Means A Recompense or Consideration Made To ADocumento1 páginaCommission, We Said That: "Salary" Means A Recompense or Consideration Made To AJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- SynopsisDocumento2 páginasSynopsisJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- NascentDocumento1 páginaNascentJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- 40Documento1 página40Jhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- MercenariesDocumento1 páginaMercenariesJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- DecisionDocumento1 páginaDecisionJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Cralaw Virtua1aw LibraryDocumento2 páginasCralaw Virtua1aw LibraryJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Chanrob1es Virtual 1aw Library: Separate OpinionsDocumento2 páginasChanrob1es Virtual 1aw Library: Separate OpinionsJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Chanrob1es Virtual 1aw LibraryDocumento2 páginasChanrob1es Virtual 1aw LibraryJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Chanrob1es Virtual 1aw LibraryDocumento2 páginasChanrob1es Virtual 1aw LibraryJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Chanrob1es Virtual 1aw LibraryDocumento4 páginasChanrob1es Virtual 1aw LibraryJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Chanrob1es Virtual 1aw LibraryDocumento3 páginasChanrob1es Virtual 1aw LibraryJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Cralaw Virtua1aw LibraryDocumento2 páginasCralaw Virtua1aw LibraryJhenjhen GandaAinda não há avaliações

- Rent Control JudgmentsDocumento30 páginasRent Control JudgmentsArun SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Great Asian Sales Center V CA (2002)Documento2 páginasGreat Asian Sales Center V CA (2002)chavit321Ainda não há avaliações

- 08 G.R. No. 160242Documento2 páginas08 G.R. No. 160242Mabelle ArellanoAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitDocumento23 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Kings Bench Division Court of Appeal All England Report (1932) Volume 2Documento4 páginasKings Bench Division Court of Appeal All England Report (1932) Volume 2EljabriAinda não há avaliações

- Case Name Antonio Geluz, Petitioner, vs. The Hon. Court of Appeals and OSCAR LAZO, Respondents. Case No. - Date Ponente FactsDocumento1 páginaCase Name Antonio Geluz, Petitioner, vs. The Hon. Court of Appeals and OSCAR LAZO, Respondents. Case No. - Date Ponente FactsKim B.Ainda não há avaliações

- Trials - Archive (19, Jan. 2005) To (27, April. 2005Documento127 páginasTrials - Archive (19, Jan. 2005) To (27, April. 2005nadia boxAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Matrix PDFDocumento611 páginasComparative Matrix PDFTin LicoAinda não há avaliações

- Ong-Chia-v-Republic-DigestDocumento1 páginaOng-Chia-v-Republic-DigestZimply Donna LeguipAinda não há avaliações

- Disini Jr. V. Secretary of Justice Facts:: Section 4 (A) (1) On Illegal AccessDocumento9 páginasDisini Jr. V. Secretary of Justice Facts:: Section 4 (A) (1) On Illegal AccessAleezah Gertrude RegadoAinda não há avaliações

- Dismissal of The Complaint Not Case Does Not Result To The Dismissal of Counterclaim Which May Be Prosecuted in The Same ActionDocumento16 páginasDismissal of The Complaint Not Case Does Not Result To The Dismissal of Counterclaim Which May Be Prosecuted in The Same ActionRommel TottocAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Mejia, 309 F.3d 67, 1st Cir. (2002)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Mejia, 309 F.3d 67, 1st Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

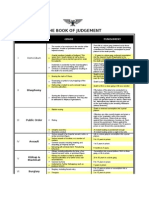

- Book of Judgement - SummaryDocumento3 páginasBook of Judgement - SummaryJon CokerAinda não há avaliações

- 1 G.R. No. L 37379 PDFDocumento1 página1 G.R. No. L 37379 PDFMaricar MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- Bhim Singh MLA Vs State of J&KDocumento4 páginasBhim Singh MLA Vs State of J&KSajid Sheikh100% (1)

- Group Insurance Enrollment/Change Form: (For Internal Use)Documento4 páginasGroup Insurance Enrollment/Change Form: (For Internal Use)Jennifer WrightAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 145226 February 06, 2004 LUCIO MORIGO y CACHO, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines, Respondent. Second Division DecisionDocumento3 páginasG.R. No. 145226 February 06, 2004 LUCIO MORIGO y CACHO, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines, Respondent. Second Division DecisionChielsea CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Quantum of Evldencelproof in Administrative CasesDocumento162 páginasQuantum of Evldencelproof in Administrative CasesJillen SuanAinda não há avaliações

- Immigration Consequences of Criminal Convictions in VirginiaDocumento22 páginasImmigration Consequences of Criminal Convictions in VirginiaBrandon Jaycox100% (1)

- Justification of Non-Availability of CerDocumento2 páginasJustification of Non-Availability of Ceranon_794869624100% (1)

- Lc249 Liability For Psychiatric IllnessDocumento137 páginasLc249 Liability For Psychiatric Illnessjames_law_11Ainda não há avaliações

- Topic 8 Ordinances & ResolutionsDocumento27 páginasTopic 8 Ordinances & ResolutionsMay AnascoAinda não há avaliações

- Himmler v. Brodbeck Et Al - Document No. 3Documento3 páginasHimmler v. Brodbeck Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digests CompilationDocumento26 páginasCase Digests CompilationAnne Laraga LuansingAinda não há avaliações

- Latogan v. PeopleDocumento16 páginasLatogan v. PeoplecitizenAinda não há avaliações

- The Indian Legal System An Enquiry 1St Edition Mahendra Pal Singh Download 2024 Full ChapterDocumento47 páginasThe Indian Legal System An Enquiry 1St Edition Mahendra Pal Singh Download 2024 Full Chapterjames.scholtens848100% (11)

- Sitaram Motiram Vs Keshav Ramchandra On 18 September, 1945Documento13 páginasSitaram Motiram Vs Keshav Ramchandra On 18 September, 1945RainhatAinda não há avaliações

- Enriquez v. The Mercantile Insurance Co., IncDocumento16 páginasEnriquez v. The Mercantile Insurance Co., IncJohn FerarenAinda não há avaliações

- BRFDocumento9 páginasBRFNeha KillaAinda não há avaliações

- Practical Training PDFDocumento14 páginasPractical Training PDFMariya Mujawar100% (2)