Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Michael Polanyi e Tacito Relativista Cognitivo

Enviado por

kkadilsonDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Michael Polanyi e Tacito Relativista Cognitivo

Enviado por

kkadilsonDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

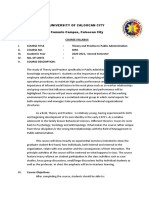

HeyJ XLII (2001), pp.

463479

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT

COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

STRUAN JACOBS

Deakin University at Geelong, Victoria, Australia

Michael Polanyi had a profound effect on the prominent theorists of

science, Feyerabend and Kuhn1 and, given the common apprehension of

these two thinkers as cognitive relativists, it may be wondered whether

Polanyi was himself a relativist. The topic is perhaps no less significant

for theology and the philosophy of religion than it is for philosophy of

science, Polanyi having exerted influence in each of these areas. In

theology, for example, Dulles, has observed that Polanyis

doctrine of the fiduciary component in human knowledge has immense significance

According to Polanyi, all acts of comprehensive knowledge either are or depend

upon faith, in the sense of a free commitment to that which could conceivably be

false If this thesis is true, theology, as the work of faith seeking understanding,

is not an anomaly among the cognitive disciplines. Religious ideas are acquired,

developed, tested, and reformed by methods at least analogous to those pursued in

the natural and social sciences.2

Turning to cognitive relativism, we find that Tillich has written of its

vogue in all forms of thought and life today. He observes relativism

rising to prominence in the most sacred and perhaps most problematic

of all realms, that of religion. It is visible today in the encounter of

religions all over the world and in the secularist criticism of religion.3

Poirier,4 Sanders5 and Echeverria6 have examined whether Polanyi was

a cognitive relativist, but I disagree with the conclusions reached by the

first two of these commentators, while my material and approach differ

appreciably from Echevarrias. It is argued below that Polanyi was an

unwitting relativist. His express rejection of relativism is contradicted

by the implications of his analysis of conceptual frameworks, and of the

gap between, and controversies concerning, frameworks.

POIRIERS VIEW

Poirier believes there are fundamental differences between the

theories of knowledge and reality of Polanyi and Kuhn, contrasting

The Editor/Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford, UK and Boston, USA.

464

STRUAN JACOBS

Polanyis realism with Kuhns relativism. In Polanyis view, Poirier

explains,

A theory is the product of insight into the real. To the extent that this insight is

truly about what is real, it is a wager that the insight will uncover more of that

order than is presently known. And, if more of the order is uncovered, then it is held

that the original contact with reality was true, since it eventually brought more

of the the true order, existing independently of man, into the ken of men.

We cannot avoid drawing attention to the fact that, for Polanyi, man the scientist

does not experience himself as being in charge of the constituents of his insight. He

is not inventor of his vision, as is the case for Thomas Kuhn. Rather, he comes

upon it, so that it might be said that he is responding to the beckoning of the real

Given all of this, how can anyone claim that Polanyi is ontologically a relativist?7

Poiriers Polanyi rejects ontological relativism or the view that groups of

people inhabit different realities. Poirier finds Polanyi affirming the

oneness or singularity of physical reality, with truth understood as bearing on that reality. Polanyian truth is an objective condition of correspondence between frameworks and the one reality. The truth of propositions

in Poiriers interpretation of Polanyi is not relative to, and variable

between, social groups or their cultures.

On at least one occasion in Personal Knowledge Polanyi explicitly

denies cognitive relativism.8 It is this strand of Polanyis thinking that

Poirier highlights. There is indirect evidence of Polanyis non-relativism

in his depiction of the controversy between Hegel and astronomers over

Bodes Law, Polanyi denying that Hegels Naturphilosophie and the

astronomers frameworks of belief were equally valid in their own terms.

Even if Bodes Law is duly shown to be a mere coincidence without

any rational foundation, Polanyi argues that the astronomers were

right and Hegel was wrong for the reason that the astronomers guess

lay within a conceivable scientific system, and was a competent guess

; while Hegels inference was altogether unscientific, incompetent.9

In another expression of non-relativism, Polanyi notes that Aristotelians

and Copernicans agreed on what they meant by true; namely, that

truth lies in the achievement of a contact with reality I believe

accordingly [writes Polanyi] in view of the subsequent history of

astronomy that the Copernicans were right in affirming the truth of the

new system, and the Aristotelians and theologians wrong in conceding

to it merely a formal advantage.10

CHARACTERIZATION OF COGNITIVE RELATIVISM

The characterization of cognitive relativism offered here largely follows

Hollis and Lukess influential formulation.11 As a major first step

toward such relativism, Hollis and Lukes identify two related

propositions.

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

(a1)

(a2)

465

Perception is not determined by its objects.

Perception is conditioned by language.

As a result:

(a3) Facts have to be perceived and identified before they can settle disputes and

by then they are already impregnated.

The crucial further step to cognitive relativism Hollis and Lukes take

to be the relativizing of truth as follows.

(b1) What people accept as true descriptions of the world is relative to their

respective semantic structures (conceptual schemes).

(b2) There is no common stock of non-relative observational truths which serve

to anchor communication, so conceptual schemes are incommensurable.

(b3) Each conceptual scheme contributes to the constitution of its own world.

Following these theses, which tie true descriptions to conceptual schemes

and affirm multiple realities and incommensurable frameworks, the final

step to full fledged cognitive relativism involves standards of rationality.

(c3) Standards for good reasons for holding beliefs cannot themselves be ranked

as they also are relative to conceptual schemes. By way of illustration,

Galileo consulted observation and experiment, Bellarmine the scriptures; EvansPritchard the available evidence of causal connections, Azande the poison oracle.

Each is equally enmeshed in a web of reasons, properly woven by its own standards

from within but finally incapable of support from without.12

Two further formulations of relativism, simpler than, but consonant

with, that of Hollis and Lukes, may be noted. For Popkin, relativism

affirms that cultural, religious and other views have to be assessed

relative to the cultures that give rise to them, there being no overall criterion for judging views true or false.13 Cunningham suggests that cognitive relativism is the denial of a governing principle such as could

ground a comparative evaluation of frameworks as approximations to

truth.14 I submit that Polanyis thought is a species of cognitive relativism by any of these standards.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

Polanyis essay, The Stability of Beliefs,15 published in 1952 and substantially reproduced in his magnum opus, Personal Knowledge (1958),

exhibits a defining tendency in his thinking.

Setting the scene, Polanyi summarizes for his readers the epistemology

he had presented in Science, Faith and Society (1946) and Scientific

Beliefs (1951). He explains that discovery, verification and falsification

of propositions in science do not obey any definite rule but proceed

with the aid of maxims which elude both precise formulation and

466 STRUAN JACOBS

rigorous evaluation. The maxims are premisses or beliefs embodied

in the tradition of science. Sustained by this tradition, science is

governed by the coherent opinion of its practitioners who converse

through the idiom of science in which its interpretative framework is

expressed.16 Scientists accept the truth of their tradition as a matter of

personal conviction, beyond empirical proof.

There are innumerable understandings of the world, Polanyi citing

Azande witchcraft, Marxism and psychoanalysis, besides science. These

conceptual frameworks are, for Polanyi, expressed in the use of, and

upheld by, their corresponding languages which form idioms of belief.17

Polanyi attributes this view to Lvy-Bruhl and he finds it confirmed in

Evans-Pritchards investigation of Azande witchcraft. Azande belief is

embedded in an idiom which interprets all relevant facts in terms of

witchcraft and oracular powers.18 Evans-Pritchard had been struck by

how effectively the Azande reason in the idiom of their beliefs and he

pointed out that they cannot reason outside, or against, their beliefs

because they have no other idiom in which to express their thoughts.19

Polanyi went on to develop a general account of the linguistic embodiment of belief systems, contending that each language has a worldview implicit in its vocabulary and structure. A vocabulary is likened

by Polanyi to the theory of chemical compounds in as much as a

vocabulary is a definite theory of all subjects that can be talked about

and a vocabulary ascribes these subjects with recurrent features to

which the words refer.20 Each such worldtheory includes certain conceptions while ruling out many others. A language permits only certain

questions to be formulated, and Polanyi writes that answers to them

inevitably confirm the theory that is implicit in the vocabulary and

structure of the language.

The thesis of worldviews as embodied in languages foreshadowing

the content of Whorfs fascinating essay-collection (1956) is repeated

by Polanyi in Personal Knowledge.21 With reference to Evans-Pritchard

and Lvy-Bruhl, Polanyi explains in Personal Knowledge that each

descriptive term of ordinary language implies a generalization affirming the stable or otherwise recurrent nature of some feature to which it

refers, and together these recurrent features constitute a theory of

the universe which is amplified by the grammatical rules according to

which the terms can be combined to form meaningful sentences.22

Polanyi says that frameworks of belief cannot be evaluated from

within. Using a given language to challenge its embodied theory produces self-contradictions. His point is that you affirm particular subjects

with specific properties in the very act of using a language; so you

contradict yourself if you use the language to deny its subjects or their

properties. A worldview can be questioned only when its language has

been surrendered for another language.23 A new idiom has to be taken

up for the expression of ideas before one can criticize the previous

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

467

framework. Polanyi quotes from Koestler and Horney who at one time

had regarded the interpretative powers of their respective Marxian and

Freudian language-frameworks as evidence of [their] truth. When

their faith collapsed, the two thinkers came to view the powers of the

systems as excessive and specious.24 The crux of Polanyis argument in

1952 was that worldviews are immanent or indwelling in languages

which are shapers as well as instruments of thought.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SCIENTIFIC CONTROVERSIES

An analysis of scientific controversy in Polanyis most important work,

Personal Knowledge, will be revealing for us. Polanyi sees controversy

as shaping the content, values and methods of science; and, at the meta

level, his analysis of scientific controversy informs his extensive argument against objectivism.25 A bloodless caricature of science, objectivism, for Polanyi, affirms that the content of scientific statements is

entirely determined by observation and logic, exclusive of personal

factors.26 Were objectivism true, Polanyi argues, scientists would settle

their differences by way of facts, reasoned argument and external criteria, by systematic and dispassionate empirical investigations.27 In

fact, says Polanyi, scientific controversies arouse intense emotions and

defy rational negotiated settlements. Objectivism is at a loss to account

for scientific controversies.

In analysing scientific controversy, Polanyi applies ideas expressed in

his 1952 paper on global frameworks to developments in science itself.

(Polanyis remarks about divergences between scientific frameworks

apply a fortiori to the even more pronounced divergences between global

frameworks such as modern science, Azande witchcraft, Marxism, and

Christianity.)

In a Polanyian scientific controversy, supporters of a heterodox conceptual framework endeavour to wrest scientific value (legitimacy)

away from orthodoxy and its upholders. Among conceptual frameworks

cited by Polanyi in this context are Freuds psychology, Eddingtons a

priori system of physics, Rhines Reach of the Mind, Lysenkos biology,

the astronomical theories of Ptolemy and Copernicus, Pasteurs account

of alcoholic fermentation as a living function of yeast, the view of

Whler, Liebig and Berzelius that yeast in fermentation is a chemical

precipitate, extra-sensory perception, epiphenomenalism and volitional

neurology.28

Polanyi says a good deal about scientists passionate commitment to

established conceptual frameworks and he attributes great malleability

to those frameworks. It is remarkable in this light that new conceptual

frameworks arise, much less that some of them eventually oust established ones from science. Orthodoxy can explain most of the evidence

468

STRUAN JACOBS

but never all of it, yet adherents, impressed by their frameworks coherence, set aside for the time being facts, or alleged facts, which it

cannot interpret.29 Supporters expect these pieces of evidence eventually to be explained, or else be explained away as spurious facts.30

Polanyi stresses frameworks resistance to, and the lack of interest of

protagonists in subjecting their frameworks to, criticism. He writes of

discrepancies often being classed as anomalies, a classic case being

the perturbations of the planetary motions that were observed during

60 years preceding the discovery of Neptune.31 These recordings were

set aside for explanation in the future, and the majority of astronomers

never viewed them as impairing the Newtonian framework.32

A scientific framework undergoes what Polanyi describes as programmatic development, its conceptions assimilating, and adapting to,

unprecedented instances the scientists tacit art of simultaneously

applying and reshaping conceptions.33 A case in point is Ureys addition

of deuterium to the isotopes of hydrogen, against the vain objection of

Soddy that this violated the meaning of isotope which required isotopes of an element to be chemically inseparable from each other. A

Polanyian framework also develops through the unfolding of its theoretical implications, with new facets of reality discovered.34 In illustration, the ancient atomists, seventeenth-century corpuscularians and John

Dalton beheld and described the dim outline of a reality which modern

atomic physics has since disclosed in detail.35

Although the theme of commitment to orthodoxy is pronounced in

Polanyis discussion, he does say that anomalies may lead to frameworks being questioned. He believes that every system of thought has

some loose ends tucked away Yet it is a fact that time and again

men have become exasperated with the loose ends of current thought

and have changed over to another system, heedless of similar deficiencies within that new system.36 Otherwise Polanyi has little to say concerning the circumstances that arouse scientists affirmative and conative

intellectual passions, urging scientists to discover frameworks and

prompting others to switch their allegiance to the new.

Going to the core of his understanding of scientific controversies,

Polanyi writes that

two conflicting systems of thought are separated [or segregated] by a logical

gap Formal operations relying on one framework of interpretation cannot

demonstrate a proposition to persons who rely on another framework. Its advocates

may not even succeed in getting a hearing from these, since they must first teach

them a new language, and no one can learn a new language unless he first trusts that

it means something.37

The idea of the logical gap between frameworks controls Polanyis

understanding of scientific controversy. He believes that conceptual

frameworks in a controversy have this logical gap in the same sense as

a problem is separated from the discovery which solves the problem.38

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

469

The logical gap between a problem and its undiscovered solution consists for Polanyi in the fact that no rule or logical procedure leads from

existing knowledge to the solution which is by its very nature unpredictable. (Maxims, being inherently vague, can only afford limited assistance to a discoverer trying to cross the gap.) As Polanyi explains it, the

logical gap between a problem and its solution has to be crossed heuristically, by the enquirer trying to guess right.39 The first-ever crossing

occurs in an intellectual leap of originality. Discontinuous with previous

knowledge, the solution combines a Gestalt mental reorganization with

emotional upheaval.

Polanyi uses the analogy of a gap between a problem and its solution

to elucidate his idea of a logical gap or disconnection between conceptual frameworks in a scientific controversy. The separation between

the contents of such frameworks is such that no relation of entailment,

contradiction or disjunction exists between them. A new framework is

not an inductive generalization, nor a deductive inference, from a

traditional one, nor does it enlarge and correct an existing framework.

The extent of the logical gap is underscored by Polanyi with the proposition that, compared to followers of an established scientific framework, supporters of a new system think differently, speak a different

language, live in a different world.40

Conceptual frameworks are needed in order to make sense of experience, each one presenting a unique vision of reality.41 Adherents

of frameworks in a controversy belong to the same material universe

but they conceptualize and experience different worlds.42 Ontologies of

frameworks being radically different, frameworks on either side of a

logical gap may have no facts in common.43

The great gap between frameworks is traced by Polanyi to their

premisses, by which he means their presuppositions. These premisses

are tacit in the minds and actions of researchers, and they constitute

objects of fiduciary commitment. An explicit statement of a scientists

premisses, Polanyi writes, serves only to disclose the premisses behind

past scientific achievements. The actual premisses of science, at the

moment of writing, are present only in the yet unformed discoveries

maturing in the minds of scientific investigators intent on their work.44

Essential elements of scientific research are embodied in these premisses:

substantive claims, principles of procedure, appreciations of cognitive

value (derived from past controversies), indications as to questions that

it should be reasonable and interesting to explore and the kind of conceptions and empirical relations that deserve to be upheld as plausible.45

(Kuhns idea of paradigms as disciplinary matrixes is redolent of Polanyis

depiction of premisses.) Formal and substantive elements of knowledge, express and tacit, are inextricably bound together in premisses.

The rules of scientific procedure which we adopt, and the scientific beliefs and

valuations which we hold, are mutually determined. For we proceed according to

470

STRUAN JACOBS

what we expect to be the case and we shape our anticipations in accordance with the

success which our methods of procedure have met with. Beliefs and valuations have

accordingly functioned as joint premisses in the pursuit of scientific inquiries.46

Polanyi goes on to say that Formal operations relying on one framework

of interpretation cannot demonstrate a proposition to persons who rely

on another framework.47 Arguments from premisses in support of a

proposition appear wholly specious from the adversarys point of view.48

In 1874 vant Hoff explained optical isomerism in terms of asymmetric

molecules, their atoms tetrahedrically arranged around a carbon atom.

Kolbe, whose conceptual framework ascribed a high valuation to experimentalism, dismissed vant Hoffs work as a tissue of fancies. It was

impossible, Kolbe decided, to argue rationally with such wild ideas.49

Premisses for Polanyi also determine what is to count as credible

evidence. Predictive successes and confirmations within a framework

have no evidential worth for scientists who are antipathetic to the framework. Polanyi notes how the nineteenth-century controversy over alcoholic fermentation dragged on for almost forty years. From 1835 several

scientists on the basis of microscopic observations were suggesting that

fermentation is a product of live yeast cells. The dominant conceptual

framework indicated that yeast as the initial cause of alcoholic fermentation is a chemical agent. Whler, Liebig and Berzelius attacked the

experimentation conducted in support of the live yeast theory as

unreliable. Supporting the conceptual framework of reductionist explanation to physics and chemistry, Whler and his allies disparaged the

other framework as vitalist.50

Because premisses differ so profoundly between conceptual frameworks, forming accounts of different worlds, even when scientists are

prepared to learn a rival frameworks language, its concepts and terms

will not suffice for an independent assessment of the comparative merits

of the heterodox and the orthodox systems. There is no neutral vantage

point from which scientists can evaluate substantive claims, evidence

and arguments, which helps to explain why scientific disagreements, in

Polanyis view, are often deep, acrimonious and long lasting. Arguments

and evidence, being internal to conceptual frameworks, do little to

restrain currents of intellectual passion. Choices between frameworks in

science are animated by passion, with no absolute, framework-independent resources to guide them.51

Adversaries in scientific controversies justify their comprehensive

rejection of the other framework by depicting it as altogether unreasonable. They resort to ad hominem attacks, denigrating the opponent as

a fool, a crank or a fraud.52 Controversies in science remind Polanyi

of ideological clashes between Marxists, Nazis and their enemies. And

once we are out to establish such charges we shall readily go on to expose

our opponent as a metaphysician, a Jesuit, a Jew, or a Bolshevik,

as the case may be.53

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

471

Notwithstanding the hostility they provoke, new conceptual frameworks may attract support. For this to occur, however, proponents of a

new system must first win others intellectual sympathy for a doctrine

they have not yet grasped.54 To understand an alien framework, scientists have to develop an empathic respect for it, for only then can the terms

of the foreign language be learned on the trusting assumption that they

have meaning. (Kolbe made no such concession to vant Hoff and his

allies, referring to them as weeds of a trivial and empty Philosophy

of Nature.)55 Protagonists of a conceptual framework use rhetorical

devices to persuade doubters of its merits. When a previously incredulous or hostile scientist becomes convinced of a new frameworks

truth, she undergoes a conversion that leads her into the ranks of the

disciples who form a school.56 In time, a new framework may entirely

replace an old orthodoxy in science.

POLANYIAN FRAMEWORKS AND THE CRITERIA OF

COGNITIVE RELATIVISM

Polanyis analysis of conceptual frameworks and of the logical gap

between such frameworks satisfies Hollis and Lukes criteria of cognitive relativism. According to propositions (a1) and (a2) in the characterization of relativism, perception is undetermined by its objects and

conditioned by language. Polanyi specifically says that frameworks

are necessary for making sense of experience, each being embodied in

its own language which conditions perceptions and beliefs about the

material universe to such an extent that followers of different frameworks live in different worlds.57 (a3) as a part of relativism asserts that

facts are biased in conflicts over frameworks. Polanyi understands

conceptual frameworks to be embedded in their own languages which

interpret all relevant facts. Each language-with-framework marks out

its own realm of subjects that can be talked about.58 For Polanyi, there is

no neutral ground from which, and no unprejudiced facts with which, to

assess frameworks in scientific controversies.

According to the relativist proposition (b1), empirical descriptions are

accepted as true only in the context of a conceptual scheme. (b2) denies

the possibility of non-relative observational truths and infers to the

incommensurability of conceptual structures and to communication

failure. The vivid impression gained from reading Polanyi is that observations and observational truths are framework-based, and that demonstrations and evidence are relative to frameworks.

Proposition (c3) in cognitive relativism describes standards for assessing reasons for beliefs as varying between conceptual frameworks.

Polanyi maintains that mutually conditioning standards, rules and valuations inhere in premisses, which are peculiar to each framework.

472

STRUAN JACOBS

Polanyis thought accords with Hollis and Lukes criteria of cognitive

relativism. In the case of global frameworks (modern science, Marxism,

Azande magic, astrology), and in scientific controversies, classifications

of objects, facts, evidence and observations are relative to frameworks.

Characteristically in scientific controversies, a whole class of alleged

facts affirmed by a new framework is at issue.59 Scientists reject any

proof that is given in the framework to which they are opposed; they

are incredulous about the objects being argued for and, a fortiori, about

the evidential support for those objects.

It was the presumption of Whler and Liebig against the idea that fermentation was

due to living cells which made them disregard the evidence in its favour. The kind

of evidence produced by vant Hoff for the asymmetrical carbon atom was condemned by Kolbe as worthless by the very nature of its argumentation. Pasteurs

evidence for the absence of spontaneous generation was rejected by his opponents

by interpreting it in their own way, and Pasteur admitted that this possibility could

not be excluded.60

Facts in one framework are dismissed as spurious by scientists

supporting another framework. Polanyi does not indicate that there is a

possibility of translation and comparison between what he in effect

suggests are incommensurable frameworks. There is no systematic and

dispassionate empirical procedure to assist with framework-choice.61 In

his Stability of Beliefs paper Polanyi says that to use an idiom is to

reaffirm and confirm its theory, and that the only alternative to this is to

learn a new theory-in-idiom. This does in fact happen when primitive

people who believe in witchcraft, etc., are gradually converted to the

European conception of universal causation.62 Likewise, proponents of

a new framework for science will not be listened to unless the orthodox

are prepared to learn a new language, and no one can learn a new

language unless he first trusts that it means something.63

SANDERSS ATTEMPT TO SHOW THAT POLANYI IS NOT A

COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

Poirier makes no mention of Polanyis Stability of Beliefs and he has

little to say regarding the doctrines of Polanyi that we have been discussing. Sanders on the other hand closely examines Polanyi on

scientific controversy and on the logical gap between frameworks, but

his Polanyi is not a cognitive relativist.

In an unpromising start to his argument, Sanders notes that Polanyi

foreshadows elements of the strong (relativist) programme in the

sociology of knowledge developed by the BarnesBloor circle at

Edinburgh University. Sanders refers to Polanyis anthropologically

flavoured approach to science and culture as when Polanyi puts Zande

magical beliefs and the beliefs of Western scientists on a par in respect

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

473

to their stability, scope, coherence and credibility.64 Nevertheless,

Polanyis explicit presentation of truth as a transcendent, obligatory

ideal, which is impossible to achieve, and his explicit insistence that

though every person may believe something different to be true, there

is only one truth convinces Sanders that Polanyi is no cognitive

relativist.65

I agree with Sanders that Polanyian truth is unitary and absolute, not

plural, so that Polanyi is not a relativist as regards the ideal of truth. But

what Sanders needs to show if he is to clinch his case that Polanyi is not

a cognitive relativist is that Polanyi provides good reasons for cognitive

choices. Does Sanders show that Polanyi has non-arbitrary grounds for

believing that frameworks are not on a par and are able to be graded as

approximations to the ideal of truth? Or perhaps Polanyi has a good

reason to say that there are some true propositions over and above those

that are true only for participants in their frameworks; some, in other

words, that are true between frameworks. If Sanders finds no convincing

arguments to these effects in Polanyi, that will secure my case that

Polanyi is a cognitive relativist according to the HollisLukess criteria.

The fact that Polanyi in discussing scientific controversies writes that

adherents of a conceptual framework think differently, speak a different

language, [and] live in a different world from supporters of another

framework does not, as Sanders recognizes, prevent Polanyi from

affirming in Personal Knowledge that science is true whereas systems

such as astrology (or Azande witchcraft) are not.66

This twofold claim about astrology and science suggests to me that

Polanyi (and Sanders) believes that on his own premisses astrology and

science are incompatible and cannot both be true, so that, believing

science to be true, Polanyi feels entitled to infer that astrology is false.

This means that Polanyi (and Sanders) fails to appreciate the force of his

doctrine of the logical gap and of his analysis of scientific controversies.

The logical gap between frameworks in scientific controversies, and a

fortiori between global systems of belief such as modern science and

astrology, effectively means that they are incommensurable or, as Polanyi

describes it, segregated. Being mutually indifferent, Polanyian frameworks

are not alternative accounts of the same subject matter; they are not

mutually incompatible descriptions of the same objects. I reiterate that

while Polanyi understands all people to live in the same reality, supporters of various frameworks are regarded by him as occupying different

theoretically organized and populated worlds. There is no relation of

contradiction/exclusion between Polanyian frameworks separated by a

logical gap. Polanyis argument from his belief in the truth of science to

astrology as being false is illicit. If Polanyi is to show that non-scientific

frameworks such as astrology and Azande witchcraft are false, his idea

of the logical gap effectively requires that he do so by way of an argument that privileges no framework, that is framework-independent.

474

STRUAN JACOBS

The very terms in which Polanyi conducts his discussion of intellectual controversies and framework-switches suggest that reasons for

preferring one conceptual framework are formulated within it and, as a

result, are question-begging to supporters of the other framework. This,

according to Polanyi, is why shifts from one framework or world picture

to another conversions are moved by non-rational forces of polemics,

browbeating, and passion; non-rational in that arguments and facts can

never justify the choice.67 A new framework involves a new way of

reasoning and it lacks suasive power for the opposition. Conversely, if

the heterodox formulate their critical argument within their [opponents]

framework, that will carry no conviction either. Demonstration must

be supplemented, therefore, by forms of persuasion which can induce a

conversion.68

Realizing that criteria of cognitive value in science are internal to it69

(and, one might add, variable within it), Polanyi appreciates that he

cannot use them to argue for the superiority of science over other systems; to use these criteria in argument is to accept the conclusion in

advance. Sanderss Polanyi principally grounds his belief in the truth of

science in convictional faith: faith in the tradition of science.70 Sanders

considers that Polanyi is correct in believing that faith in the tradition

of science serves to establish science as cognitively superior to nonscientific systems. But I would point out that science is not peculiar in

respect of its resting on faith; believers in Azande witchcraft or in

astrology have faith in their respective traditions. Faith, for Polanyi, is

involved in every framework: Augustine taught that all knowledge was

a gift of grace, for which we must strive under the guidance of antecedent belief No intelligence, however critical or original, can operate

outside a fiduciary framework.71

Moreover, Polanyis fallacy, noted above, in arguing from the (alleged)

truth of science to the (alleged) falsity of astrology is repeated in his

invocation of faith. Even were Polanyis fiduciary belief accepted as

establishing the truth of science, given his understanding of logical gaps,

that truth is indifferent with respect to astrology. Astrology and other frameworks may be true in their own terms, generating their own knowledge

claims, standards, arguments and evidence. A separate argument is needed

to show that the framework of astrology is false, and Sanderss Polanyi

fails to provide it.

Having argued (unsuccessfully) against classifying Polanyi as a

cognitive relativist, Sanders proposes that Polanyis position be

designated as reliabilism, to reflect what Sanders says is Polanyis

belief that science is the most reliable guide to new knowledge and

truth about nature.72 For Polanyi, Sanders argues,

Science is reliable and trustworthy in a twofold sense. First, in accordance with

the doctrine of tacit knowing, science functions at a subsidiary level in modern

mans search for new and, it is hoped, ever better [how can this hold for Polanyian

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

475

frameworks, separated from each other by a logical gap?] knowledge of nature. In

fact, he cannot but rely on it Second, the conditioning role of a culture and

concomitant conceptual schemes [is so strong that] completely divesting oneself

from them is impossible.73

Contrary to Sanders, neither consideration in this passage is an argument for science as providing the most reliable guide to nature. What

Sanders gives are pragmatic considerations as to why science is typically relied on in modernity. He notes that at times Polanyi appears to be

saying that science is simply a form of life and that any justification of

it has to be put in terms of that life, so that Polanyi may seem to be

suggesting on a more general level that believers in any given framework are entitled to say that it is reliable and truthful.74 All such

systems would, on this interpretation of Polanyi, be in the same boat

where truth/falsity are concerned. Were this indeed Polanyis view,

Sanders agrees, one would have to conclude that he is a radical

relativist.75

Echeverria proposes an interpretation of Polanyi according to which

the beliefs of a frame of reference defined entirely in its own native

terms are uncriticizable ab externo.76 Sanders admits that there are some

prima facie grounds for [this] interpretation, including Polanyis

emphasis on persuasion in deciding scientific controversies, his contention that different interpretative frameworks divide men into groups

which cannot understand each others way of seeing things and acting

upon them and, finally, his idea that a real dialogue can only occur

between participants [belonging] to a community accepting on the

whole the same teaching and traditions for judging their own affirmations.

But, argues Sanders, In my view it is a mistake to understand these

Polanyian ideas as deep and normative epistemological insights. Rather,

they should be interpreted in a descriptive sense; they point out practical,

though relevant, difficulties in the actual practice of understanding,

criticising and the like.77

Sanders is correct in regarding Polanyis points as descriptive, but

Sanders cites no text (and the present author has failed to find primary

material) to support his (false) suggestion that inter-framework misunderstandings and disagreements are, for Polanyi, tractable by fact and

argument, not insurmountable.78 Sanderss suggestion flies in the face of

all that Polanyi writes on scientific controversies.

The criticism of another framework must, according to Sanderss

Polanyi, proceed in light of our own local standards and ideals which

are, in fact, the only standards and ideals available to us.79 Sanders

further remarks that it is mainly on account of modern science and its

concomitant naturalistic outlook, qualified by ideals like truth, justice

and charity, that Polanyi takes our local culture as superior.80 Neither of

these claims shows that Polanyi is not a cognitive relativist, and the

second claim (superiority) is question-begging. Neither claim serves to

476 STRUAN JACOBS

clear Polanyi of the charge of cognitive relativism since neither claim

amounts to a framework-independent argument that science, or any of its

constituent frameworks, more closely approximates the ideal end of truth

than do other global frameworks, and neither provides a frameworkindependent criterion or argument for judging propositions as true or

false. Polanyis premisses the nature of frameworks, logical gaps, and

controversies involving frameworks prevent him from providing these

things. We are, Polanyi believes, fated to operate in some framework or

other and there is a circularity, he says, in making use of any framework,

as for example when he self-consciously distinguishes competent from

incompetent thought in light of his own interpretative framework.81

Sanders concludes that Polanyi was certainly no advocate of radical

relativism, nor does his position entail the theoretical or practical

impossibility of criticism.82 A more penetrating question that Sanders

should have asked (but failed to) is not whether Polanyi expressly

advocates or denies relativism, nor whether criticism is possible

(Polanyis highlighting of the logical gap indicates that inter-framework

critical argument will always be beside the point),83 but whether Polanyis

account of frameworks of belief, of the logical gap and scientific controversy implies cognitive relativism. The argument of this article is that

his account does indeed carry this implication.

EPILOGUE

Polanyi admits of no general framework-independent criterion nor any

neutral argument for regarding one conceptual framework with its

standards, propositions, evidence and arguments as true in a non-relative

sense. Further, the possibility of comparatively grading frameworks

according to their approximation to the ideal of truth is excluded by

Polanyis logical gap idea. Polanyian frameworks separated by a logical

gap are not competing approximations to the truth.84 One acquires a

framework, in Polanyis account, either by learning or by passionate

adoption, rather than by a reasoned argument showing it is the best

available approximation to the truth.

An upshot of my argument in this article is that Christian theologians

and philosophers who accept that Christianity is a repository of absolute

truth need to exercise caution when it comes to making constructive use

of Polanyis ideas. They must properly appreciate what his doctrines

affirm and imply. By analogical extension from his view of scientific

frameworks, separated by a logical gap, it would follow that the framework of, say, Roman Catholicism has its own mutually determining

beliefs, language, methods, rules and valuations; and that truth, facts and

evidence are relative to to this framework which is open to no independent appraisal. Arguments within the framework would be circular,

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

477

while comparison of this framework to others with regard to the truth

would be out of the question.85

Notes

1 I document this claim in my Polanyis Presagement of the Incommensurability Concept,

forthcoming in Studies in History and Philosophy of Science.

2 Avery Dulles, Faith, Church, and God: Insights from Michael Polanyi, Theological Studies

45 (1984), p. 537. Other works by philosophers of religion and theologians informed by Polanyi

include the following: T. F. Torrance (ed.), Belief in Science and in Christian Life: The Relevance

of Michael Polanyis Thought for Christian Faith and Life (Edinburgh: Handsel Press, 1980);

Martin Moleski, Self-Emptying Knowledge: The Tacit Apprehension of Mysteries in Science and

Religion in R. Gelwick (ed.), From Polanyi to the 21st Century (Biddeford, ME: University of New

England, 1997), pp. 41434; and see also the essays by Neidhardt, Crewdson and Apczynski in the

same volume; and Echeverrias works as cited in note 6 below. The journals, Appraisal and

Tradition & Discovery often include discussion of Polanyis religious ideas and implications of his

thought for theology. Several studies of religion drawing from Polanyis thought are cited by

Richard Allen, Polanyi (London: The Claridge Press, 1990), p. 78.

3 Paul Tillich, My Search for Absolutes (New York: Simon and Shuster, 1964), pp. 646; and

12443. Further indications of cognitive relativisms importance for religion appear in Michael

Krausz (ed.), Relativism (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1989), pp. 18, 1301,

2645, 3026, 3223, and 3812.

4 Maben Poirier, A Comment on Polanyi and Kuhn, The Thomist 53 (1991), pp. 25979.

5 Andy Sanders, Michael Polanyis Post-Critical Epistemology (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1988).

6 Eduardo Echeverria, Polanyi on Truth and Justification in R. Gelwick (ed.), From Polanyi to

the 21st Century, pp. 83040; and Eduardo Echeverria, Criticism and Commitment (Amsterdam:

Rodopi, 1981), pp. 59ff. Echeverria concentrates on the Azande worldview or global framework

and its relation (or lack thereof) to science, whereas I also find striking evidence of Polanyis

implied cognitive relativism within the global system to which Polanyi devotes most attention,

science itself.

7 Poirier, Comment pp. 2712; cf. Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge (London: Routledge

& Kegan Paul, 1958), pp. 56, 64.

8 Polanyi, ibid., pp. 31516.

9 Ibid., pp. 1545.

10 Ibid., p. 147, and see also pp. 12, 1489.

11 Martin Hollis and Steven Lukes, Introduction in Hollis and Lukes (eds.), Rationality and

Relativism (Oxford: Blackwell, 1982), pp. 811, emphasis added. Neither of these authors, it

should be noted, is a cognitive relativist.

12 Ibid., p. 10.

13 Richard Popkin, Relativism, The Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 12 (New York: Macmillan,

1987), p. 274.

14 R. L. Cunningham, Relativism, New Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 13 (New York: McGrawHill, 1967), p. 223.

15 Michael Polanyi, The Stability of Beliefs, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science

3 (1952), pp. 21732.

16 Ibid., pp. 21819.

17 Ibid., p. 220.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid., p. 221, emphasis added.

20 Ibid.

21 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, pp. 80, 94, 112, 287, 289.

22 Ibid., p. 94.

23 Polanyi Stability of Beliefs, pp. 2212.

24 Ibid., p. 218.

25 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, pp. 159, 170 and references to objectivism in the Index.

26 Ibid., pp. 1517, 214.

27 Ibid., p. 159.

28 Ibid., pp. 1518.

29 Ibid., p. 151.

478

STRUAN JACOBS

30 Ibid., pp. 13, 47, 51, 138, 158, 167.

31 Ibid., p. 20, emphasis added.

32 Ibid.; Michael Polanyi, Scientific Beliefs, Ethics 61 (1950), p. 29.

33 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, pp. 1056.

34 Ibid., pp. 5, 104, 147, 160.

35 Ibid., p. 104.

36 Ibid., p. 18. At times (e.g., ibid., p. 147) Polanyi loses sight of this cautionary note,

pronouncing on certain frameworks as though they are categorically true.

37 Ibid., p. 151.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid., pp. 125, 143.

40 Ibid., p. 151 emphasis added.

41 Ibid., pp. 60, 135, 150.

42 Ibid., pp. 47, 151.

43 Ibid., pp. 47, 158, 167. The Ptolemaic and Copernican frameworks could both account for the

known facts (ibid., p. 152), but Polanyi appears to regard this case as exceptional. Typically,

controversies over factual evidence disclose to Polanyi the power of theory over facts: the two

sides do not accept the same facts as facts, and still less the same evidence as evidence For

within two different conceptual frameworks the same range of experience takes the shape of

different facts and different evidence. Indeed, one side may disregard some of the evidence

altogether in the confident expectation that it will somehow turn out to be false (ibid., p. 167).

44 Ibid., pp. 59, 165.

45 Ibid., pp. 135, 15861, 170.

46 Ibid., p. 161 emphasis added.

47 Ibid., p. 151.

48 Ibid., p. 158.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid., pp. 1567.

51 Ibid., p. 152.

52 Ibid., p. 151 emphasis added.

53 Ibid., pp. 1512.

54 Ibid., p. 151.

55 Ibid., p. 155.

56 Ibid., p. 151.

57 Ibid., pp. 47, 60, 1501.

58 Polanyi, Stability of Beliefs, pp. 2201; also Personal Knowledge, p. 150.

59 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, p. 150; also pp. 97 and 296.

60 Ibid., p. 275.

61 Ibid., p. 159 and p. 150. For rule-proving exceptions see p. 157, n. 4.

62 Polanyi, Stability of Beliefs, p. 222.

63 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, p. 151.

64 Sanders, Post-Critical Epistemology, p. 186.

65 Ibid., p. 187 quoting Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, p. 315, and also referring to Personal

Knowledge, p. 245; and Michael Polanyi, Science, Faith and Society (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1963), pp. 71ff.

66 It is not entirely clear what Polanyi intends in describing the (entire) tradition of science as

true, when he also indicates that not all frameworks in the history of that tradition are true. My best

guess is that he means, at the minimum, that the tradition of science is cognitively superior to, has

greater truth content than, other traditions.

67 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, pp. 157 and 167.

68 Ibid., p. 151; see also p. 159.

69 Ibid., p. 160.

70 Sanders, Post-Critical Epistemology, pp. 198201, 2045.

71 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, p. 266, emphasis added.

72 Sanders, Post-Critical Epistemology, p. 202.

73 Ibid., emphasis added.

74 Ibid., p. 203. See Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, p. 171 for text suggesting that Polanyian

science is a form of life. The same, I have argued in effect in this article, is true of frameworks

within science.

75 Sanders, Post-Critical Epistemology, p. 203.

MICHAEL POLANYI, TACIT COGNITIVE RELATIVIST

479

76 Sanders, ibid., p. 204, quoting Echeverria, Criticism and Commitment, p. 75.

77 Sanders, ibid., p. 204, quoting Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, pp. 112 and 378.

78 Ibid., p. 204.

79 Ibid., p. 205.

80 Ibid., pp. 2078.

81 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, pp. 299, 31819.

82 Sanders, Post-Critical Epistemology, p. 208.

83 Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, pp. 1578, reminding us that controversies in science are seen

by Polanyi as animated and settled by passion, which is inevitable as the adversaries have no

common framework within which a more impersonal procedure could be followed.

84 The underlying issue is well explained by Anthony OHear, An Introduction to the Philosophy

of Science (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), pp. 68, 735. See also John Preston, Feyerabend

(Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997), pp. 74, 193ff.

85 As usual, my research owes a great deal to the efficiency with which members of the Deakin

University Library, Geelong particularly Christine Oughtred and the Inter-library-loans staff

have obtained essential works for me. I thank Dr Mike Leahy most sincerely for his detailed and

acute comments on this article in draft, and for his having drawn my attention to some instructive

secondary sources.

Você também pode gostar

- Polanyi and RealismDocumento9 páginasPolanyi and RealismCubanMonkeyAinda não há avaliações

- Essay Concerning Human Understanding (SparkNotes Philosophy Guide)No EverandEssay Concerning Human Understanding (SparkNotes Philosophy Guide)Ainda não há avaliações

- Michael Polanyi and Thomas KuhnDocumento12 páginasMichael Polanyi and Thomas KuhnPEDRO HENRIQUE CRISTALDO SILVAAinda não há avaliações

- Contact with Reality: Michael Polanyi’s Realism and Why It MattersNo EverandContact with Reality: Michael Polanyi’s Realism and Why It MattersNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Michael Polanyi and Alvin Plantinga Help From Beyond The Walls-1Documento21 páginasMichael Polanyi and Alvin Plantinga Help From Beyond The Walls-1Pedro Henrique Cristaldo SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- The Reach of The Aesthetic and Religious Naturalism: Peircean and Polanyian ReflectionsDocumento20 páginasThe Reach of The Aesthetic and Religious Naturalism: Peircean and Polanyian ReflectionsparlateAinda não há avaliações

- An Essay Concerning Human UnderstandingDocumento6 páginasAn Essay Concerning Human UnderstandingKrishnaAinda não há avaliações

- Is Science Very Different From Religion? A Polanyian PerspectiveDocumento13 páginasIs Science Very Different From Religion? A Polanyian PerspectiveMarcelo DutraAinda não há avaliações

- Some Answered QuestionsDocumento125 páginasSome Answered QuestionsFábio LamimAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 1 - Nat Sci Vs Soc SciDocumento31 páginasLecture 1 - Nat Sci Vs Soc Scivera obfanAinda não há avaliações

- Ul21ba037 - IPP ProjectDocumento9 páginasUl21ba037 - IPP Projectpriyanshukumarsingh191Ainda não há avaliações

- AssignmentDocumento2 páginasAssignmentAkula ModyAinda não há avaliações

- QUINE. TWO DOGMAS OF EMPIRICISMdocxDocumento16 páginasQUINE. TWO DOGMAS OF EMPIRICISMdocxBankong EmmanuelAinda não há avaliações

- Ee For Ib ServerDocumento19 páginasEe For Ib ServerIvanCoHe (IvanCoHe)Ainda não há avaliações

- Propositional Logic, Also Known As Sentential Logic and Statement Logic, Is The Branch of Logic ThatDocumento4 páginasPropositional Logic, Also Known As Sentential Logic and Statement Logic, Is The Branch of Logic ThatMuhammad TariqAinda não há avaliações

- Normative Reasoning and Moral Argumentation in Theory and PracticeDocumento26 páginasNormative Reasoning and Moral Argumentation in Theory and PracticenobugsAinda não há avaliações

- Popper, The Logic of Scientific DiscoveryDocumento4 páginasPopper, The Logic of Scientific DiscoveryManuelAinda não há avaliações

- Com Preens ÃoDocumento19 páginasCom Preens ÃoWellington CastanhaAinda não há avaliações

- Salzman 2001Documento28 páginasSalzman 2001Anna Carolina BarrosAinda não há avaliações

- Handout Berkeley First DialogueDocumento14 páginasHandout Berkeley First DialoguebezimenostAinda não há avaliações

- Thopbs 1Documento10 páginasThopbs 1Valentina CoyAinda não há avaliações

- 3 2+transcriptDocumento2 páginas3 2+transcriptPedro Borges Do AmaralAinda não há avaliações

- A Reduction of Doxastic Logic To ActionDocumento19 páginasA Reduction of Doxastic Logic To ActionetiembleAinda não há avaliações

- Barnes en Bloor - NieuwDocumento14 páginasBarnes en Bloor - NieuwpietpaaltjenAinda não há avaliações

- Reconciling Psychoanalytic Ideas With Attachment Theory: Provided by UCL DiscoveryDocumento66 páginasReconciling Psychoanalytic Ideas With Attachment Theory: Provided by UCL DiscoveryAmrAlaaEldinAinda não há avaliações

- READING RESPONSE: Bonjour's "A Critique of Foundationalism"Documento5 páginasREADING RESPONSE: Bonjour's "A Critique of Foundationalism"Patrick Shannon100% (2)

- αὐτάρκης in Stoicism and Phil 4.11Documento20 páginasαὐτάρκης in Stoicism and Phil 4.11Alexander BurgaAinda não há avaliações

- Broad 1915 Review Proceedings AristotelianDocumento3 páginasBroad 1915 Review Proceedings AristotelianStamnumAinda não há avaliações

- SEMINAR TOPIC PRESENTATION EditedDocumento21 páginasSEMINAR TOPIC PRESENTATION Editedfavourclems123.comAinda não há avaliações

- April 2014: Student: Tim Earney-543195 Course: Independent Study Project-157400023 Lecturer: DR Cosimo ZeneDocumento23 páginasApril 2014: Student: Tim Earney-543195 Course: Independent Study Project-157400023 Lecturer: DR Cosimo ZeneMarcia BorbaAinda não há avaliações

- Neoplatonism and The Bahá'í Writings: Ian KlugeDocumento53 páginasNeoplatonism and The Bahá'í Writings: Ian KlugeBVILLARAinda não há avaliações

- RUDDER - The Falsification Fallacy PDFDocumento21 páginasRUDDER - The Falsification Fallacy PDFKary QuintellaAinda não há avaliações

- Summary of Kohlberg (1971) From Is To Ought: How To Commit The Naturalistic Fallacy and Get Away With It in The Study of Moral DevelopmentDocumento25 páginasSummary of Kohlberg (1971) From Is To Ought: How To Commit The Naturalistic Fallacy and Get Away With It in The Study of Moral DevelopmentTopher HuntAinda não há avaliações

- FalsifiabilityDocumento38 páginasFalsifiabilityjavim8569Ainda não há avaliações

- Paul and The PersonDocumento12 páginasPaul and The PersonNeacsu MihaiAinda não há avaliações

- Hume'S Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion: Proseminarska Naloga Pri Predmetu EmpirizemDocumento11 páginasHume'S Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion: Proseminarska Naloga Pri Predmetu EmpirizemFrojdovski OpažajAinda não há avaliações

- Dewey Between Hegel and DarwinDocumento17 páginasDewey Between Hegel and DarwinVitaly KiryushchenkoAinda não há avaliações

- Alkon Gunjevic PDFDocumento19 páginasAlkon Gunjevic PDFJuan Manuel CabiedasAinda não há avaliações

- Rorty 1966Documento5 páginasRorty 1966Erik Novak RizoAinda não há avaliações

- Quantum Physics, Philosophy, and The Image of God: Insights From Wolfgang Paul1Documento14 páginasQuantum Physics, Philosophy, and The Image of God: Insights From Wolfgang Paul1Raúl Rojas MejíasAinda não há avaliações

- Martin Mahner and Mario Bunge PDFDocumento11 páginasMartin Mahner and Mario Bunge PDFTiago SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Comments and Queries The Ambivalence of Psychology Toward Philos 1968Documento3 páginasComments and Queries The Ambivalence of Psychology Toward Philos 1968Remy ZeroAinda não há avaliações

- Epistemic Relativism: Mark Eli Kalderon November 22, 2006Documento13 páginasEpistemic Relativism: Mark Eli Kalderon November 22, 2006Carolina MircinAinda não há avaliações

- Developing Critical Thinking: Needs To Be Aware of Other Paradigms Than TheirsDocumento5 páginasDeveloping Critical Thinking: Needs To Be Aware of Other Paradigms Than TheirsturgayozkanAinda não há avaliações

- Freud EpistemologijaDocumento7 páginasFreud EpistemologijaMateja PavlicAinda não há avaliações

- Innatism, Empiricism and MysticismDocumento13 páginasInnatism, Empiricism and MysticismGabriel RossiAinda não há avaliações

- WPIAAD Vol1 RosenbergDocumento12 páginasWPIAAD Vol1 RosenbergmhdstatAinda não há avaliações

- Final Finals FinalsDocumento3 páginasFinal Finals FinalsEmmanuel John CochingAinda não há avaliações

- Idealism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Documento95 páginasIdealism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)GitauAinda não há avaliações

- Kebenaran IlmuDocumento10 páginasKebenaran IlmuutiarahmahAinda não há avaliações

- ¿La Intuición Es Central en La Filosofìa?Documento16 páginas¿La Intuición Es Central en La Filosofìa?Diego MontoyaAinda não há avaliações

- Foucault TodayDocumento31 páginasFoucault TodayCalypsoAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Documento25 páginasEvidence (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)juanAinda não há avaliações

- Schopenhauer On Idealism, Indian and European (Christopher Ryan)Documento19 páginasSchopenhauer On Idealism, Indian and European (Christopher Ryan)Neel PODDERAinda não há avaliações

- Ocr Philosophy A Level Revision PackDocumento22 páginasOcr Philosophy A Level Revision PackHubert SelormeyAinda não há avaliações

- Swabey Locke Theory of IdeasDocumento22 páginasSwabey Locke Theory of IdeasFaber Tenorio AlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- Can't Say All Neg Interps Counter Interps, Rob That Includes ADocumento20 páginasCan't Say All Neg Interps Counter Interps, Rob That Includes ATanish KothariAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To The Philosophy of Human PersonDocumento5 páginasIntroduction To The Philosophy of Human PersonJoelina ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy of Mind - Locke's Arguments Against Innate Ideas and KnowledgeDocumento5 páginasPhilosophy of Mind - Locke's Arguments Against Innate Ideas and KnowledgeVictoria Ronco57% (7)

- Entrevista Com Francesco BertoDocumento7 páginasEntrevista Com Francesco BertokkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Bigaj Essentialism and Modern PhysicsDocumento32 páginasBigaj Essentialism and Modern PhysicskkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Gustavo Barros Herbert A. Simon e o Conceito de RacionalidadeDocumento18 páginasGustavo Barros Herbert A. Simon e o Conceito de RacionalidadekkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Emotion and UnderstandingDocumento9 páginasEmotion and UnderstandingkkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- A Priori Intuitions Analytic or SynthetiDocumento26 páginasA Priori Intuitions Analytic or SynthetikkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Facts Values and ObjectivityDocumento44 páginasFacts Values and ObjectivitykkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Revolutionary Insight Daniele Moyal-ShaDocumento9 páginasRevolutionary Insight Daniele Moyal-ShakkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Bigaj Causation Without InfluenceDocumento26 páginasBigaj Causation Without InfluencekkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- What in A Mental Picture Updated VersionDocumento16 páginasWhat in A Mental Picture Updated VersionkkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Abduction Versus Inference To The Best ExplanationDocumento3 páginasAbduction Versus Inference To The Best ExplanationkkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Renata Zieminska Two Notions or Internal Ea Epistemic Externalism GoldamnDocumento6 páginasRenata Zieminska Two Notions or Internal Ea Epistemic Externalism GoldamnkkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Begaj Introduction To Metaphysics in Contemporanea FísicaDocumento16 páginasBegaj Introduction To Metaphysics in Contemporanea FísicakkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Hegel 5Documento18 páginasHegel 5kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- The Epistemological Status of Managerial Knowledge and The Case MethodDocumento11 páginasThe Epistemological Status of Managerial Knowledge and The Case MethodkkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 11Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 11kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 8Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 8kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Hegel'S Theory of Mental Activity: An Introduction To Theoretical SpiritDocumento21 páginasHegel'S Theory of Mental Activity: An Introduction To Theoretical SpiritkkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Hegel 3Documento15 páginasHegel 3kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Science, Teleology, and .InterpretationDocumento17 páginasScience, Teleology, and .InterpretationkkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 9Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 9kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 6Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 6kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 8Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 8kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 7Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 7kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 3Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 3kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 6Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 6kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 4Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 4kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 2Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 2kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy 136 Handout 1Documento2 páginasPhilosophy 136 Handout 1kkadilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Glenn StockwellDocumento6 páginasGlenn Stockwellbatoula aloeveraAinda não há avaliações

- Secondary UnitDocumento36 páginasSecondary Unitapi-649553832Ainda não há avaliações

- A Cognitive and Social Perspective On The Study of Interactions - Emerging Communication - Studies in New Technologies and PRDocumento280 páginasA Cognitive and Social Perspective On The Study of Interactions - Emerging Communication - Studies in New Technologies and PRariman_708100% (1)

- Mapping Research Methods: Kevin O'Gorman and Robert MacintoshDocumento25 páginasMapping Research Methods: Kevin O'Gorman and Robert MacintoshsugunaAinda não há avaliações

- Drives by Gary PattersonDocumento6 páginasDrives by Gary Pattersonapi-208346542Ainda não há avaliações

- Maqa Id and The Renewal by Rezart Beka-1Documento43 páginasMaqa Id and The Renewal by Rezart Beka-1Rezart BekaAinda não há avaliações

- Syllabus in Theory and Practice in Public AdministrationDocumento6 páginasSyllabus in Theory and Practice in Public AdministrationLeah MorenoAinda não há avaliações

- Judit - Teachers' Professional Development On Problem SolvingDocumento141 páginasJudit - Teachers' Professional Development On Problem SolvingSella Ayu NindyaAinda não há avaliações

- Master Thesis Lindsay Vogelzang 11736925Documento89 páginasMaster Thesis Lindsay Vogelzang 11736925hana fentaAinda não há avaliações

- Pages 20-23 From (13 Peter Newmark - Textbook of Translation)Documento4 páginasPages 20-23 From (13 Peter Newmark - Textbook of Translation)Eliane MasonAinda não há avaliações

- A Student Guide To Writing Research Reports Papers Theses and DissertationsDocumento235 páginasA Student Guide To Writing Research Reports Papers Theses and DissertationsaghowelAinda não há avaliações

- Approaches Key Concepts and Ideas Strengths Weakness: Sikolohiyang PilipinoDocumento1 páginaApproaches Key Concepts and Ideas Strengths Weakness: Sikolohiyang PilipinoJaneAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Issues in International Management Research: An Agenda For Future AdvancementDocumento16 páginasCritical Issues in International Management Research: An Agenda For Future AdvancementNhat Nhan NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Gary Kilehofner MohoDocumento6 páginasGary Kilehofner MohoDanonino12Ainda não há avaliações

- Schelling Concept of Self OrganizationDocumento21 páginasSchelling Concept of Self OrganizationGustavo Adolfo DomínguezAinda não há avaliações

- Socionics Scalability of Complex Social SystemsDocumento322 páginasSocionics Scalability of Complex Social SystemsEseoghene EfekodoAinda não há avaliações

- Takis Kayalis, Anastasia Natsina - Teaching Literature at A Distance - Open, Online and Blended Learning-Continuum (2010) PDFDocumento219 páginasTakis Kayalis, Anastasia Natsina - Teaching Literature at A Distance - Open, Online and Blended Learning-Continuum (2010) PDFAhlemLouatiAinda não há avaliações

- Rob Cover - Identity and Digital Communication - Concepts, Theories, Practices-Routledge (2023)Documento193 páginasRob Cover - Identity and Digital Communication - Concepts, Theories, Practices-Routledge (2023)Betül Önay DoğanAinda não há avaliações

- Notes On Deconstructing The Popular NotesDocumento2 páginasNotes On Deconstructing The Popular NotesRajkumari ShrutiAinda não há avaliações

- Media Economics: Presented by Majid Heidari PHD Student Media MangementDocumento43 páginasMedia Economics: Presented by Majid Heidari PHD Student Media MangementangenthAinda não há avaliações

- CT Observ 2 GravityDocumento3 páginasCT Observ 2 Gravityapi-300485205Ainda não há avaliações

- Reading TestDocumento8 páginasReading TestLan NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Brummel 2021Documento33 páginasBrummel 2021franzAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis On Knowledge Management in Higher EducationDocumento8 páginasThesis On Knowledge Management in Higher EducationJoe Andelija100% (1)

- Physics Dissertation IdeasDocumento7 páginasPhysics Dissertation IdeasCanSomeoneWriteMyPaperForMeSaltLakeCity100% (1)

- Metopen Artikel Design Research NotesDocumento9 páginasMetopen Artikel Design Research NotesTondy DmrAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Research Part 2Documento6 páginasLegal Research Part 2shubham kumarAinda não há avaliações

- A Semantic:Syntactic Approach To Film Genre - RICK ALTMAN - COMMENTDocumento5 páginasA Semantic:Syntactic Approach To Film Genre - RICK ALTMAN - COMMENTpepegoterayalfmusicAinda não há avaliações

- Tree of PhilosophyDocumento400 páginasTree of PhilosophyJimmy100% (2)

- Research Methodology For Economic Sciences - 1Documento22 páginasResearch Methodology For Economic Sciences - 1Givemore ChiwanzaAinda não há avaliações

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNo EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (7)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionNo EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (51)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (30)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosNo Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (207)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYNo EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (4)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyNo EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (7)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessNo EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (85)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentNo EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (17)

- Meditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionNo EverandMeditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (15)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNo EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (4)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsNo EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (9)

- A Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to WittgensteinNo EverandA Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to WittgensteinNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklNo EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (101)

- Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and EnlightenmentNo EverandWhy Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and EnlightenmentNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (753)

- There Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindNo EverandThere Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (71)

- Knocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldNo EverandKnocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (64)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessNo EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (60)

- You Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsNo EverandYou Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (6)

- Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemNo EverandMoral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (115)

- The Jew in the Lotus: A Poet's Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist IndiaNo EverandThe Jew in the Lotus: A Poet's Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist IndiaAinda não há avaliações