Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Rabkin On Books

Enviado por

Ernesto ContrerasTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Rabkin On Books

Enviado por

Ernesto ContrerasDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Fam Proc 11:107-112, 1972

BOOKS

RABKIN ON BOOKS

The recent governmental decline in the funding of research may give search a chance. We may see novelty and

originality again, qualities that have not predominated in federally sponsored scientific studies. Characteristically, research

proposals submitted to the National Institutes of Health and allied agencies are so thoroughly worked out that they closely

resemble the papers published at the conclusion of the project, except that the results anticipated in the proposal are

presumably confirmed in the final paper. In the Preface to his new work, The War with Words: Structure and

Transcendance (Mouton, 1971), Harley Shands has charged that most of the agencies to which he had applied for support

were conservative, inflexible, and elitist in the sense of requiring membership in a professional guild. In his introductory

remarks he indulges in a type of bitter nose-thumbing at those agencies which wouldn't fund his work because it wasn't

research but "only" search, or speculative inquiry as he calls it. His feelings, while slightly too sensitive, are easily shared.

In spite of all the calls from government sources for imaginative research, maverick research, creative research, there is

never any hint that these agencies realize that what they are actually referring to is just plain search. Established institutions

seldom willingly support a big risk. A formal research proposal itself precludes this. It would be like asking Columbus for a

detailed map of the area he wished to explore. With the government now reducing its level of research support, the climate

may change in favor of those who are involved in speculative endeavors. The history of scientific discoveries is the history

of how scientists got around the restrictions on their speculative drives.

The Empirical Structural Coincidence

One of the most interesting ways in which men stumble on scientific finds is through a coincidence, a particular type of

configuration leading to an accidental glimpse of certain underlying relationships that differ from prevailing views. As

examples, let us consider events in three areas: genetics, ecology, and family therapy from a systems point of view.

Gregor Mendel published his great work in 1866, which was written in the clearest possible manner, but was ignored

during his lifetime basically because scientists of the time were so busily researching Darwin's work. Evolution as a

concept oriented them to look for areas that would reconfirm Darwin's idea that a series of subtle and slight variations

gradually led to the emergence of new species. Unlike his peers, Mendel was dealing with big differences, and so his ideas

went unnoticed until 1900 when men with non-Darwinian interests went looking back through the literature. How then did

Mendel manage to work so effectively in an unpopular domain? No doubt many processes contributed, but one of them was

the happy coincidence between the empirical material (in this case, pea plants) and the underlying structure being studied

(in this case, genes). If he had chosen another plant, whose phenotypical characteristics were involved with several genes

not as nicely separated as they were on the chromosomes of pea plants, he would never have arrived at correct conclusions.

Another example concerns lakes. Originally botanists regarded the material in a lake as merely an aggregation of several

distinct species: floating plants, bottom plants, etc. The associated animals were considered the biotic factor. Physics and

chemistry were simply overlooked. The botanist was interested in classification, in the inner anatomy of the plant, and in its

sex life, so to speak. If he happened to meet a zoologist while at a lake, he would not be surprised to find that the zoologist

thought of animals as aggregations also: bottom animals, surface animals, etc. Perhaps the botanist would feel slightly hurt

to find his entire field of study being relegated, in the eyes of the zoologist, to the status of "the habitat." At some point in

the development of science, the contradictions in this earlier view were resolved by introducing the concept of a

communitya floating community and a bottom community that included both animals and plants.

In the final theoretical step, the lake itself began to take on unexpected dimensions, being seen as the main object to

study. It became difficult to determine the status of slowly dying pondweeds covered with periphytes, some of which were

also continually dying, since the non-living ooze into which they sank was rapidly reincorporated through dissolved

nutrients back into the living animals and plants. Was this mass living or dead, animal, plant, mineral? It was hard to

distinguish the biological in a contrasting sense from the physicochemical. Allee (1) in 1934 first expressed the view of the

lake as a whole by using the metaphor of a superorganism. Tansley (2), in 1935, rejected the notion of superorganism and

proposed instead that of ecosystem. I think this was possible and occurred in the study of lakes, instead of other places such

as deserts, because the underlying living structure, the ecosystem in the case of the lake, happened to coincide conveniently

with the empirical material. Thus, even in the old days of aggregations, the botanist realized that he was developing a

specialty, limnology, that had to do with lakes, while when he was collecting his plants on a desert, he just knew the

environment was hot and dry. Just as Mendel was fortunate to "use" peas to discover genetics, these men were fortunate to

"use" lakes to discover the new ecology.

For studying families, or thinking about institutions from the point of view of systems, the same sort of empirical,

1

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

structural coincidences occurred. Families and institutions just "happened" to be like large networks or collections of

objects related in some functional sense. For example, in a family therapy session many members might take a position in

the room analogous to positions in the underlying family structure; they might move around and change rapidly enough for

the systems nature of the underlying structure to be brought to awareness. In a parenting-sibling system (3) in which an

older sibling takes on many parental duties with regard to the younger siblings, its operation can be made evident by

sending the parenting sibling out of the room. Following this, a remarkable shifting of positions might occur with someone

who looks mentally deficient at one moment sparkling at the next, while someone else takes the role of "dummy." This

empirical food for thought might not be present in a verbal report such as might be offered in individual psychotherapy.

Structuralism

If, as I am suggesting, progress in science occurs by speculation that is frequently aided by a coincidental isomorphism

between the empirical material and something called an underlying structure, it pays to think about what we mean by the

term ecosystem, or structure. Furthermore, what is it that prevents us from looking for structures directly? Piaget's two

recent books, Structuralism (Basic Books, 1970) and Genetic Epistemology (Norton, 1971), as well as Michael Lane's

Introduction to Structuralism (Basic Books, 1970), attempt to give some idea of what an underlying structure is. While

their books are difficult reading because they were not designed for psychotherapists, they are valuable to workers in this

field. A structure (for instance, a family from a systems point of view) is characterized by three things:

1. Wholeness. Gestaltists speak of the whole being more than the sum of its parts and, therefore, of a family as being more

than the individual people. This is not structuralism. A structure is independent of its parts. What is primary for a structure

is the arrangement, not the elements; the relationships may, as Piaget suggests, have an objective, independent existence. In

the case of the structure called a family, this relationship is kept going with people related by blood, by inducting the

therapist into the system, by buying dogs, houses, etc. to promote the integrity of the family structure.

2. Transformations. A structure is a system of transformations, or as the modern artist would put it, a happening. The best

examples come from myths. When the princess kisses the frog, she transforms him into a prince. Marriage, to pick a less

mythical example, is also a powerful transformation. Suddenly, if the magic is performed correctly, you are husband and

wife. (While some people might argue that marriage is on the way out and is as mythic as the princess and the frog story,

and still others might argue it is merely legal, a piece of paper. I, for one, can testify that it changed me, transformed me,

personally at least, as much from a frog to a prince, or a prince to a frog.)

3. Homeostatic Processes. Family homeostasis was one of the earliest observations to be made in systems-oriented family

therapy. On a bleak January day in 1954, Don Jackson gave a lecture at the Palo Alto VA hospital on the topic of family

homeo-stasis. Gregory Bateson was in the audience and felt this topic was closely related to the "double-bind" project on

which he was working with Jay Haley and John Weakland. The resulting collaboration created the Mental Research

Institute and indirectly, with the help of Nathan Ackerman's Family Institute, this journal.

Perhaps now we can consider what prevents scientists from looking for structures. Structuralists believe in the

supernatural, perpetual motion, and something like teleologyall highly taboo subjects for scientists. Ecosystems and

structures are not empirical entities but reside on a plane or in a sphere that the ordinary man cannot reach or touch.

Therefore, one could say that they are supernatural. The concept of transformations takes the place of the notion that work

must be paid for with energy, that change takes work. It defies the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Homeostatic processes

can sustain the notion of purpose in a system without having to rely on the idea of motives. In short, a mother's influence

does not fall off by the inverse of the square root of the distance It defies the law of gravity. Until the systems points of view

regarding purpose, perpetual motion, and magic and the supernatural are widely known, it will be much too

unconventional, and even eccentric, to think directly about structures, and progress may have to wait for coincidences.

Constructionism and Social Design

The clinical arm of systems theory and structuralism is yet another jaw-breaking, ugly term: constructionism. It appears

in Piaget's two books when he discusses development and, by implication, clinical issues. If we take courting or getting

married as an example, different approaches reveal three different clinical models: empirical, nativist, and constructionist.

The empiricist believes that when Mr. Right comes along, Miss Lonely will get married. Although few clinicians support

this view, certainly various social clubs, dating bars, mixers, and so forth, do. In contrast, the nativist concentrates on inner

space. He favors the right time rather than the right person. When Miss Lonely finally is ready for marriage, when she

overcomes her inner blocks and lets it happen, she will get married. Most clinicians fit in here. Both of these approaches

treat marriage as an already known event. The constructionist or systems therapist, on the other hand, thinks of marriage as

a project, probably taking ten to fifteen years to complete involving as many as four generations with the possibility of

several alternative designs. Marriage, in this view, is not a known event, but a unique, one-of-a-kind construction or

structure. Helping with such projects is, therefore, the task of social design, which I would define as the modification,

stabilization, renovation, construction, and/or dismantling of human social systems.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The social systems to which such help may be applied can vary from a two-person relationship to that of a new town.

The systems therapist's task of social design is closely allied with other design professionals, particularly architectual

planners and legislative reformers. The ultimate concern of social design is for the total ecology or environment. Its

scientific roots lie in comparative ecology, a relatively new field, that has encouraged several family therapists to take an

interest in animal "families." One of the few articles on the subject is by Ito entitled "Groups and Family Bonds in Animals

in Relation to Their Habitat," which appeared in Development and Evolution of Behavior (4). In this article he offers the

provocative idea that only the crow, the wolf, probably some apes, and man have sufficient mental development in relation

to the problems presented by the environment to allow for a family group to develop without sacrificing the larger group, or

vice versa. Environmental problems, however, may be too complex now for man to continue to be in that elite company.

We could probably manage with the problems presented to crows and wolves, even some apes, but can we manage the

problems presented to man? Ito's book Comparative Ecology has not yet been translated from the Japanese, although his

article is in excellent English.

Another source of material for social design comes from the study of single cases such as Herbst's book, Behavioral

Worlds (Barnes and Noble, 1971). By making the assumption that each social organization is unique, he arrives at

constructionism from a methodologist's point of view. In his forthcoming book entitled Socio-Technical Theory and

Design he asks many of the same questions that tantalize those interested in social design.

Here in the United States there are few advocates of structuralism, systems theory, constructionism, comparative

ecology, and social design. In France Piaget reports the opposite problem. Structuralism is so fashionable he must

apologize for its popularity at cocktail parties. Perhaps now that research monies are not so abundant, these intriguing,

controversial disciplines will attract more pioneers. Perhaps speculative inquiry will become as popular as it is in France.

Dr. Shands, take heart.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

Allee, W. C., Concerning The Organization of Marine Coastal Communities, Ecological Monographs, 4,

541-554, 1934.

Tansley, A. G., The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms, Ecology, 16, 284-307, 1935.

Rabkin, J. and Rabkin, R., "Delinquency And The Laterial Boundary of the Family," in P. Graubard (Ed.)

Children Against Schools, Chicago, Follett, 1969.

Aronson, L. R., Tobach, E., Leurman, D. S. and Rosenblatt, J. S., Development and Evolution of Behavior,

Essays in Memory of T. C. Schneirla, San Francisco, W. H. Freeman and Co., 1970.

Beginning with this note, in addition to book reviews, this section will include general reviews of publishing

houses of interest to readers.

Research Press Company, 2612 North Mattis Avenue, Champaign, Illinois 61820 catalog available.

Robert W. Parkinson writes: "We contracted for Living With Children when Research Press was no more than a husband

and wife enterprise in which my wife typed invoices and I packed books on the kitchen table. In two very short years we

have grown to a staff of twenty people with a 6000 sq. ft. building of our own and a sales volume of approximately $85,000

per month. That is what Living With Children has done for the economy"what has it done for families of children?

"Everyday we receive some very positive form of reinforcement from a parent or from those who work with parents.

Often the letters are written on colorful, flavored stationery telling of the gratifying behavioral changes in a child which the

lovely ladies attribute to a reading of Living With Children. The steady flow of domestic orders attests to the flavor Living

With Children has found among professionals. And, the fact that it is under license to firms in Brazil, Mexico, Munich,

Quebec, and Holland attests to the universality of the message of this primer in behavior modification.

"Research Press first published Living With Children in the fall of 1968. It was not long before we found it to be a most

worthy book to launch our firm. The cash flow generated by sales has been adequate to fund publication of How to Use

Contingency Contracting in the Classroom, Trick or Treatment, and most of the current list. Aside from giving Research

Press meaning and vigor, Living With Children has established itself as an historic volume; a classic introduction to social

learning theory and the behavioral methods derived from it.... No weighty tomes for us. We wish to translate good research

into usable form for people who need it."

The Psychiatric Disorders of Childhood., 2nd ed. Charles R. Shaw, M.D. and Alexander R. Lucas, M.D, New York,

Appleton-Century Crofts (Meredith Corp.), 1970. 480 pp. $12.

Readers of Family Process may be interested in William M. Bolman's observations of this book published in the

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

American Journal of Psychiatry October 1971 (Vol 128, No 4. page 505):

Family therapy is presented as "a special type of group therapy espoused mainly by Ackerman," which should be

avoided in a pathologic family group because of the risk of dangerous repercussions

R. R

Você também pode gostar

- Cultural Transmission and Evolution A QuantitativeDocumento4 páginasCultural Transmission and Evolution A QuantitativeΡΟΥΛΑ ΠΑΠΑΚΩΣΤΑAinda não há avaliações

- The Story of the Living Machine: A Review of the Conclusions of Modern Biology in Regard / to the Mechanism Which Controls the Phenomena of Living / ActivityNo EverandThe Story of the Living Machine: A Review of the Conclusions of Modern Biology in Regard / to the Mechanism Which Controls the Phenomena of Living / ActivityAinda não há avaliações

- Soto & Sonnenschein (2018) - Reductionism, Organicism, and Causality in The BiomedicalDocumento15 páginasSoto & Sonnenschein (2018) - Reductionism, Organicism, and Causality in The BiomedicalDimitris HatzidimosAinda não há avaliações

- Body, Discourse, and The Turn To Matter: Jason GlynosDocumento20 páginasBody, Discourse, and The Turn To Matter: Jason GlynospierdayvientoAinda não há avaliações

- Book Reviews: Humanity and Nature: Ecology, Science and Society by Y. Haila & R. Levins. LondonDocumento4 páginasBook Reviews: Humanity and Nature: Ecology, Science and Society by Y. Haila & R. Levins. LondonMosor VladAinda não há avaliações

- The University of Chicago Press The History of Science SocietyDocumento4 páginasThe University of Chicago Press The History of Science SocietyGertrudaAinda não há avaliações

- The New Biology: A Battle between Mechanism and OrganicismNo EverandThe New Biology: A Battle between Mechanism and OrganicismAinda não há avaliações

- 2001EthologyDaan PDFDocumento3 páginas2001EthologyDaan PDFNsangwaAinda não há avaliações

- Essays: Scientific, Political, & Speculative (Vol. 1-3): Complete EditionNo EverandEssays: Scientific, Political, & Speculative (Vol. 1-3): Complete EditionAinda não há avaliações

- University of GroningenDocumento3 páginasUniversity of GroningenNsangwaAinda não há avaliações

- (Hypatia Vol. 19 Iss. 1) JOSEPH ROUSE - Barad's Feminist Naturalism (2004) (10.1111 - j.1527-2001.2004.tb01272.x) - Libgen - LiDocumento20 páginas(Hypatia Vol. 19 Iss. 1) JOSEPH ROUSE - Barad's Feminist Naturalism (2004) (10.1111 - j.1527-2001.2004.tb01272.x) - Libgen - LiJosh SofferAinda não há avaliações

- Conceptual ThinkingDocumento9 páginasConceptual ThinkingGuaguanconAinda não há avaliações

- Problems of Life and Mind. Second SeriesDocumento430 páginasProblems of Life and Mind. Second Seriesprates.sammAinda não há avaliações

- Entangled Worlds: Religion, Science, and New MaterialismsNo EverandEntangled Worlds: Religion, Science, and New MaterialismsAinda não há avaliações

- Rouse On Barad Agenital RealismDocumento20 páginasRouse On Barad Agenital RealismZehorith MitzAinda não há avaliações

- The Song of the Cell: An Exploration of Medicine and the New HumanNo EverandThe Song of the Cell: An Exploration of Medicine and the New HumanNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (78)

- JONAS, Hans. The Phenomenon of Life Towards A Philosophical BiologyDocumento6 páginasJONAS, Hans. The Phenomenon of Life Towards A Philosophical BiologyMarco Antonio GavérioAinda não há avaliações

- The Languages of Nature - When Nature Writes to ItselfNo EverandThe Languages of Nature - When Nature Writes to ItselfAinda não há avaliações

- Edward Wilson - Sociobiology. The New Synthesis (25th Anniversary Edition)Documento910 páginasEdward Wilson - Sociobiology. The New Synthesis (25th Anniversary Edition)Javier Sánchez100% (5)

- Return to the Brain of Eden: Restoring the Connection between Neurochemistry and ConsciousnessNo EverandReturn to the Brain of Eden: Restoring the Connection between Neurochemistry and ConsciousnessNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (2)

- On Human Nature by E.O. WilsonDocumento138 páginasOn Human Nature by E.O. Wilsonjayg76100% (5)

- Turning To Ontology in Studies of Distant Sciences: Nicholas JardineDocumento25 páginasTurning To Ontology in Studies of Distant Sciences: Nicholas JardineronaldotrindadeAinda não há avaliações

- Book Reviews: PW.W . Indwid. Dill. Vol. 4. No. 5. Pp. 575-580. 1983 PergamonDocumento1 páginaBook Reviews: PW.W . Indwid. Dill. Vol. 4. No. 5. Pp. 575-580. 1983 PergamonJuan Carlos Sanchez JimenezAinda não há avaliações

- Who Needs ParadigmsDocumento14 páginasWho Needs ParadigmseugeniaAinda não há avaliações

- Helmuth Plessner and The Presuppositions of Philosophical NaturalismDocumento8 páginasHelmuth Plessner and The Presuppositions of Philosophical NaturalismJan GulmansAinda não há avaliações

- Theoretical Entities StatusDocumento25 páginasTheoretical Entities StatusJoel J. LorenzattiAinda não há avaliações

- Belief Language and Experience - Rodney PDFDocumento6 páginasBelief Language and Experience - Rodney PDFjanlorenzAinda não há avaliações

- Wallace The Farce of Physics 1994Documento98 páginasWallace The Farce of Physics 1994asdf12123Ainda não há avaliações

- Book Review: Basic and Applied Ecology 15 (2014) 720-721Documento2 páginasBook Review: Basic and Applied Ecology 15 (2014) 720-721TatendaAinda não há avaliações

- Darwin's Entangled Bank: Pluralism vs Fundamentalism in EvolutionDocumento12 páginasDarwin's Entangled Bank: Pluralism vs Fundamentalism in EvolutionJosé Luis Gómez RamírezAinda não há avaliações

- The New Naturalism and its Impact on Our Understanding of HumannessDocumento5 páginasThe New Naturalism and its Impact on Our Understanding of HumannessSiervo Inutil LianggiAinda não há avaliações

- Para - Dek-: Wid-Es-Ya-, Suffixed Form of RootDocumento30 páginasPara - Dek-: Wid-Es-Ya-, Suffixed Form of RootPavlo RybarukAinda não há avaliações

- FinalDocumento12 páginasFinalFlorencito RivasAinda não há avaliações

- The Heavy Burden of Proof for Ontological NaturalismDocumento23 páginasThe Heavy Burden of Proof for Ontological NaturalismMir MusaibAinda não há avaliações

- BOAS - The Limitation of The Comparative Method in AnthropologyDocumento8 páginasBOAS - The Limitation of The Comparative Method in AnthropologyVioletta PeriniAinda não há avaliações

- Wallace Ethics and Sociology 1898Documento30 páginasWallace Ethics and Sociology 1898fantasmaAinda não há avaliações

- 2084470Documento3 páginas2084470diaAinda não há avaliações

- Folk Biology and The Anthropology of Science Cognitive Universals and Cultural ParticularsDocumento63 páginasFolk Biology and The Anthropology of Science Cognitive Universals and Cultural ParticularsGaby ArguedasAinda não há avaliações

- Srhepaper PDFDocumento20 páginasSrhepaper PDFZain BuhariAinda não há avaliações

- Bonner, Evolution of Culture, Introduction, 3-11Documento19 páginasBonner, Evolution of Culture, Introduction, 3-11bogusia.przybylowskaAinda não há avaliações

- Sociobiology The New Synthesis Twenty Fifth Anniversary Edition 2nd Edition Ebook PDFDocumento62 páginasSociobiology The New Synthesis Twenty Fifth Anniversary Edition 2nd Edition Ebook PDFryan.riley589100% (39)

- Thesis 07 SimpleDocumento26 páginasThesis 07 SimpleYimeng WangAinda não há avaliações

- New Ontologies? Reflections On Some Recent Turns' in STS, Anthropology and PhilosophyDocumento21 páginasNew Ontologies? Reflections On Some Recent Turns' in STS, Anthropology and Philosophypedro luisAinda não há avaliações

- Hugh Drummond (Auth.), Paul Patrick Gordon Bateson, Peter H. Klopfer (Eds.) - Perspectives in Ethology - Volume 4 Advantages of Diversity (1981, Springer US)Documento253 páginasHugh Drummond (Auth.), Paul Patrick Gordon Bateson, Peter H. Klopfer (Eds.) - Perspectives in Ethology - Volume 4 Advantages of Diversity (1981, Springer US)Mauro AraújoAinda não há avaliações

- Archaeus 2Documento105 páginasArchaeus 2charlesfortAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Science in Anthropology?Documento5 páginasWhat Is Science in Anthropology?ArannoHossainAinda não há avaliações

- Roger TriggDocumento18 páginasRoger TriggRusu Loredana-IulianaAinda não há avaliações

- Book Review: The Cambridge Companion To The Philosophy of Biology.-EditedDocumento2 páginasBook Review: The Cambridge Companion To The Philosophy of Biology.-EditedAizen SousukeAinda não há avaliações

- Evolution - September 1957 - Nitecki - WHAT IS A PALEONTOLOGICAL SPECIESDocumento3 páginasEvolution - September 1957 - Nitecki - WHAT IS A PALEONTOLOGICAL SPECIESHormaya ZimikAinda não há avaliações

- Oliver Sacks The Ecology of Writing ScienceDocumento19 páginasOliver Sacks The Ecology of Writing Sciencesandroalmeida1Ainda não há avaliações

- Physical Anthropology Research Paper IdeasDocumento5 páginasPhysical Anthropology Research Paper Ideasafnkjdhxlewftq100% (1)

- Dawkins and Biological DeterminismDocumento4 páginasDawkins and Biological DeterminismdennistrilloAinda não há avaliações

- Genetics and EugenicsDocumento518 páginasGenetics and EugenicsTapuwa ChizunzaAinda não há avaliações

- Books: Family Therapy: Full-Length Case Studies, PEGGY PAPP (Ed.), M.S.W., For The American OrthopsychiatricDocumento6 páginasBooks: Family Therapy: Full-Length Case Studies, PEGGY PAPP (Ed.), M.S.W., For The American OrthopsychiatricErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 08.a Review of Family TherapyDocumento6 páginas08.a Review of Family TherapyErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 13.a Family Systems Approach To Illness-Maintaining Behaviors in Chronically III Adolescents - FreyDocumento7 páginas13.a Family Systems Approach To Illness-Maintaining Behaviors in Chronically III Adolescents - FreyErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 07.the War With WordsDocumento7 páginas07.the War With WordsErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 10.a ReviewDocumento11 páginas10.a ReviewErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Journal Note: F. Peter LaqueurDocumento1 páginaJournal Note: F. Peter LaqueurErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 07.A Re-AppraisalDocumento7 páginas07.A Re-AppraisalErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Abstracts of Literature: Abstracted by Ira D. GlickDocumento2 páginasAbstracts of Literature: Abstracted by Ira D. GlickErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 08.rae Weiner - WaltersDocumento1 página08.rae Weiner - WaltersErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Hawking's Paper on Conservation of Matter in GRDocumento6 páginasHawking's Paper on Conservation of Matter in GRErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 07.the Use of Teaching StoriesDocumento3 páginas07.the Use of Teaching StoriesErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Family Process Volume 23 Issue 2 1984 (Doi 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1984.00216.x) - Rejoinder To Scott by Michael A. HarveyDocumento4 páginasFamily Process Volume 23 Issue 2 1984 (Doi 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1984.00216.x) - Rejoinder To Scott by Michael A. HarveyErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Rald H. Zuk - Family Therapy For The "Truncated" Nuclear FamilyDocumento7 páginasRald H. Zuk - Family Therapy For The "Truncated" Nuclear FamilyErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 05.mordecai KaffmanDocumento15 páginas05.mordecai KaffmanErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Rald H. Zuk - Value Systems and Psychopathology in Family TherapyDocumento19 páginasRald H. Zuk - Value Systems and Psychopathology in Family TherapyErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 06.florence Kaslow Bernard Cooper Myrna Linsenberg - Family Therapist Authenticity As A Key Factor in OutcomeDocumento16 páginas06.florence Kaslow Bernard Cooper Myrna Linsenberg - Family Therapist Authenticity As A Key Factor in OutcomeErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Abstracts: Fam Proc 10:365-372, 1971Documento5 páginasAbstracts: Fam Proc 10:365-372, 1971Ernesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 05.cary E. Lantz - Strategies For Counseling Protestant Evangelical FamiliesDocumento15 páginas05.cary E. Lantz - Strategies For Counseling Protestant Evangelical FamiliesErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 03.the ShadowDocumento10 páginas03.the ShadowErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Family-Based HIV Prevention ModelDocumento16 páginasFamily-Based HIV Prevention ModelErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Family Process Volume 44 Issue 2 2005 Michal Shamai - Personal Experience in Professional Narratives - The Role of Helpers' Families in Their Work With TerrorDocumento13 páginasFamily Process Volume 44 Issue 2 2005 Michal Shamai - Personal Experience in Professional Narratives - The Role of Helpers' Families in Their Work With TerrorErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding How Early Marital Representations Predict Later ConflictDocumento14 páginasUnderstanding How Early Marital Representations Predict Later ConflictErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Family Process Volume 46 Issue 4 2007 (Doi 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00230Documento20 páginasFamily Process Volume 46 Issue 4 2007 (Doi 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00230Ernesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Me 43 IssDocumento15 páginasMe 43 IssErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Complex Love As Relational Nurturing: An Integrating Ultramodern ConceptDocumento15 páginasComplex Love As Relational Nurturing: An Integrating Ultramodern ConceptErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Doi 10.1111/j.1545Documento17 páginasDoi 10.1111/j.1545Ernesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Volume 37 IssDocumento22 páginasVolume 37 IssErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Family Process Volume 52 Issue 4 2013 Tseliou, Eleftheria - A Critical Methodological Review of Discourse and Conversation Analysis Studies of Family TherapyDocumento20 páginasFamily Process Volume 52 Issue 4 2013 Tseliou, Eleftheria - A Critical Methodological Review of Discourse and Conversation Analysis Studies of Family TherapyErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Books Received in Family Process JournalDocumento2 páginasBooks Received in Family Process JournalErnesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Process Volume 36Documento13 páginasProcess Volume 36Ernesto ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- 2021 CATALOG: Wood BetonyDocumento92 páginas2021 CATALOG: Wood BetonyDaveAinda não há avaliações

- Unit-3 KOE-076 PDFDocumento93 páginasUnit-3 KOE-076 PDFAnjaliAinda não há avaliações

- Bari SP FinalDocumento3 páginasBari SP Finalmosaddiq rahaman rahiAinda não há avaliações

- Bignoniaceae I PDFDocumento133 páginasBignoniaceae I PDFBrandon CruzAinda não há avaliações

- The Fungi Which Cause Plant DiseasesDocumento776 páginasThe Fungi Which Cause Plant DiseasesRosales Rosales Jesús100% (1)

- Botanical Pharmacognosy of AndrographisDocumento4 páginasBotanical Pharmacognosy of AndrographisNongton DeBitAinda não há avaliações

- Philippines Crop Statistics Report 2017-2021Documento45 páginasPhilippines Crop Statistics Report 2017-2021Erika Ruth LabisAinda não há avaliações

- Farm Tools and Equipment GuideDocumento7 páginasFarm Tools and Equipment GuideSherry GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- ArecanutDocumento51 páginasArecanutApooAinda não há avaliações

- DLL-AGRICROP 2NDQ-9th-weekDocumento8 páginasDLL-AGRICROP 2NDQ-9th-weekAve AlbaoAinda não há avaliações

- Ethnobotany Study of Medicinal Plants Used by Wolio Sub-Ethnic PeopleDocumento12 páginasEthnobotany Study of Medicinal Plants Used by Wolio Sub-Ethnic Peoplechairunnisa syafa ainaAinda não há avaliações

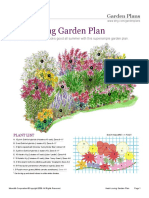

- Heat-Loving Garden PlanDocumento3 páginasHeat-Loving Garden PlanIulia Radu100% (1)

- Set-Up 1A: Control (Uncontaminated)Documento10 páginasSet-Up 1A: Control (Uncontaminated)AuraPayawanAinda não há avaliações

- Biological Sciencepunnet SquareDocumento5 páginasBiological Sciencepunnet Squarehendrix obcianaAinda não há avaliações

- Apples - Botany, Production, and Uses (2004)Documento2 páginasApples - Botany, Production, and Uses (2004)smb 09Ainda não há avaliações

- The Cry Violet, an extinct endemic plant species from FranceDocumento6 páginasThe Cry Violet, an extinct endemic plant species from FranceSanket PunyarthiAinda não há avaliações

- Decimal code charts growth stages of cerealsDocumento7 páginasDecimal code charts growth stages of cerealsLuis DíazAinda não há avaliações

- Maryland Using Native Plants For Butterfly GardensDocumento2 páginasMaryland Using Native Plants For Butterfly GardensFree Rain Garden ManualsAinda não há avaliações

- CPT 103 - Lecture5Documento72 páginasCPT 103 - Lecture5Esperanza CañaAinda não há avaliações

- How To Farm BetterDocumento96 páginasHow To Farm Bettercdwsg254100% (4)

- 2021 Tennessee Weed Control GuideDocumento111 páginas2021 Tennessee Weed Control GuideAllanAinda não há avaliações

- Feasibility of Aloe Vera (Sip)Documento2 páginasFeasibility of Aloe Vera (Sip)Paupau Tolentino100% (3)

- Beekeeping Bee Pasturage in IndiaDocumento9 páginasBeekeeping Bee Pasturage in Indiarpgmanjeri100% (3)

- Bio CH6 F5 StudywithadminDocumento7 páginasBio CH6 F5 StudywithadminRathi MalarAinda não há avaliações

- Extending The Shelf Life of Cut Rose.Documento7 páginasExtending The Shelf Life of Cut Rose.April DalloranAinda não há avaliações

- Reproduction in Flowering Plants: "Imperfect or Incomplete Flowers"Documento7 páginasReproduction in Flowering Plants: "Imperfect or Incomplete Flowers"Luz ClaritaAinda não há avaliações

- PPrt172 3-5 Plant Pathogen AntagonistsDocumento26 páginasPPrt172 3-5 Plant Pathogen AntagonistsJohannah Marie ParejaAinda não há avaliações

- 2020-03-01 BBC Gardeners WorldDocumento180 páginas2020-03-01 BBC Gardeners WorldrossAinda não há avaliações

- Log Phase: Test Taker's AnswerDocumento4 páginasLog Phase: Test Taker's AnswerCpdineshAinda não há avaliações

- Edible NutsDocumento209 páginasEdible Nutsalfa158955Ainda não há avaliações

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNo EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNo EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (13)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementNo EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (40)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesNo EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (34)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeAinda não há avaliações

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingNo EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsNo EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityNo EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNo EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (78)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsNo EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.No EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (110)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsAinda não há avaliações

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsAinda não há avaliações

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsNo EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (169)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaNo EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeNo EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (253)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassNo EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (23)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNo EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (8)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessNo EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (327)

- Recovering from Emotionally Immature Parents: Practical Tools to Establish Boundaries and Reclaim Your Emotional AutonomyNo EverandRecovering from Emotionally Immature Parents: Practical Tools to Establish Boundaries and Reclaim Your Emotional AutonomyNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (201)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryNo EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (44)

- Nonviolent Communication by Marshall B. Rosenberg - Book Summary: A Language of LifeNo EverandNonviolent Communication by Marshall B. Rosenberg - Book Summary: A Language of LifeNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (49)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossNo EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (4)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingNo EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1138)