Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Applied Ethology - It's Task and Limits in Veterinary Practice

Enviado por

Francesca TeeDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Applied Ethology - It's Task and Limits in Veterinary Practice

Enviado por

Francesca TeeDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Applied Animal Behaviour Science 59 1998.

3948

Applied ethologyits task and limits in veterinary

practice

H.H. Sambraus

Department for Animal Husbandry and Animal Behaiour of the Technical Uniersity of Munich, D-85350

Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany

Abstract

In the animal welfare laws of several European countries terms such as appropriate for the

animals behaviour and freedom of movement for the activity needs of the animals occur. When

a veterinarian has to decide whether the conditions in a husbandry system are animal specific or

not, he first looks at the hygienic conditions. The reason is: the veterinarian has learned about

hygiene, but not about ethology. Ethology has 2 aspects. It is, like anatomy and physiology, part

of the biology of an animal and like these subjects, it should be taught at the beginning of the

veterinary curriculum. The amount of teaching in ethology should be similar to that of anatomy

and physiology. In this part of the course the ethograms of all domesticated species should be

considered. There is also a quantitative component that includes questions like: how often can a

bull mate in a day? Or: how often does a calf suck from its mother in a day? In this part of his

course the veterinarian-to-be must also learn how to handle animals. In the clinical part of the

study of veterinary medicine abnormal behaviour and its therapy should be considered. An

abnormal behaviour is a substantial and continuing deviation from the behavioural norm. Such

deviations may include: altered behaviour patterns, actions at non-adequate objects, actions

without object vacuum activity.; and apathy. Some examples are mentioned, where abnormal

behaviour patterns occur in different function circles. Despite a clear definition in some cases it is

impossible to decide whether a behaviour pattern is abnormal or if it is an adaptation to a special

situation. As an example, food flinging in cattle is mentioned. q 1998 Elsevier Science B.V. All

rights reserved.

Keywords: Behaviour; Ethology; Abnormal behaviour; Animal welfare; Analogy

1. Ethology and veterinary medicine

Experienceat least in central Europeshows the following: when a veterinarian

has to decide whether the conditions in a husbandry system are species specific or not,

he first looks at the hygienic conditions. Although they appear in many European animal

welfare laws, the following conditions seems to be of lesser importance.

0168-1591r98r$19.00 q 1998 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

PII S 0 1 6 8 - 1 5 9 1 9 8 . 0 0 1 1 9 - 1

40

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

Is the husbandry system appropriate for the animals behaviour?

Is there enough freedom of movement for the activity needs of the animals?

The reasons for this rather one-sided judgement is that the veterinarian has learned

about hygiene but not about ethology. This may have been the extreme in past

generations of veterinarians, but it is generally not the case for those trained in recent

years. However, these rather unflattering views of ethology cannot be put aside.

Let us review the importance of ethology in the education of veterinary science. In

Germany, behaviour science ethology. and animal welfare are examination subjects.

Students are tested on these subjects at the very end of the study. Naturally the

appropriate lectures are given at the end of the course and they are included in a package

of subjects, including animal epidemics, judicial veterinary medicine, animal welfare,

behaviour science and vocational science. Sixty hours are provided for all these subjects

combined. Dividing these into equal hours allows only 12 h each for ethology and

animal welfare.

Two things seem to be badly structured here: first the scope of behavioural science

and animal welfare and secondly, their placement at the end of the course of study.

Ethology is concerned with behaviour patterns of animals. Together with anatomy

and physiology, ethology gives comprehensive and complete picture of the biology of an

animal. This knowledge of the biological being is the basis of veterinary science. It is

self-evident at all places of veterinary education, that anatomy with histology and

embryology. and physiology with biochemistry and physiology of nutrition. are taught

at the beginning of the curriculum. Likewise it should be self-evident that the teaching

of ethology should also occur at that time of study.

Also, the amount of teaching in ethology should orientate towards anatomy and

physiology. After the German certified system440 h are taught in the fields of

anatomy, histology and embryology. The subjects of physiology, biochemistry and

physiology of nutrition are taught for another 300 h. No one should demand a few

hundred hours of study in ethology also without further thought. The extent of the study

should be dependent upon: the volume of the entire special knowledge and its importance to the specific trainee for the veterinary profession.

In the pre-clinical part of the study, 2 aspects of ethology should be covered:

fundamental principles and ethograms of the individual species.

Included in these fundamental concepts, in which the veterinarian is often confronted

in practice, are terms like: key stimulus, vacuum activity, accumulation of action

specific energy and releasing mechanism.

Such fundamental principles should be taught in their own lecture. I believe 30 h of

study to be sufficient.

With the ethograms of the individual species, all functional circles are to be

considered, including: social behaviour, sexual behaviour, mother-infant-behaviour, etc.

Every student of veterinary science should know, however, before entering the

clinical part of his study where he has direct contact with the animal. which motor

patterns belong to the normal behaviour of each animal species.

In social behaviour, for example, he must not only know how the animals fight with

each other; he must also understand the behavioural patterns of the conflict. An animal

never attacks without previous notification and it shows aspects of expressive behaviour

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

41

prior to the attack. Only those who understand and take notice of this expressive

behavioure.g., threateningcan avoid an attack in future confrontations with the

animal.

This is an example of the qualitative part of ethology. There is also a quantitative

component that includes questions like: how often can a bull mate in a day? How often

does a calf suck from its mother in a day?

Consider the problems of fertility in a herd of cattle. There could be more questions

raised about fertility when a bull is mating than when one is not. The reason for reduced

fertility in the latter case is easy to explain. When decreased fertility occurs when a bull

is mating, the problem could be that the bull has a restrained libido. The bulls libido is

dependent on its breed, age, nutrition, condition of health and the husbandry conditions.

The bulls of beef breed mate essentially fewer times a day than those of the dual-purpose breeds. In a herd of 50 cows, it is very possible that there are 5 or 6 cows in heat in

a day. An AberdeenAngus bull would encounter too much in such a situation, leading

to too many breedings and decreased fertility; however, a Simmenthal bull would not.

The veterinarian-to-be should, for example, also know that a calf sucks 68 = from

its mother a day in the first months of its life. If calves are raised without a mother, they

only get milk replacer twice a day. By deviating from the biological norm, problems

concerning health can appear. For these aspects of ethology, I reckon 30 h of study to be

sufficient.

There is a third aspect to consider. The veterinarian-to-be must not only know the

behaviour of the animal. He must also be able to handle it. He must know how to

approach an animal and know how to calm it down. He must know in which order to

treat the animals when treating the whole group. The theoretical knowledge is insufficient here. One must have practical experience of at least one time, to learn and

memorise the reactions of the animals.

Today, such things are discussed in the propaedeutic parts of veterinary courses. It

should be stressed here the ethological conceptions also must be conveyed. In the

clinical part of the study of veterinary practice, all ethological aspects should be covered

already, apart from that which is pathological, like abnormal behaviour or behavioural

disorders and their therapy.

It is equally difficult to define the term behavioural disorders as is to define the

term illness. One could make it easy and say that a behavioural disorder is a

substantial and continuing deviation from the behavioural norm. This means that we

must know what the normal behaviour is. This may be taken for granted, as the

recognition and understanding of normal behaviour is covered in the pre-clinical part of

the study. Still, it is not always easy to say whether a specific behaviour is disturbed or

whether one must accept the behaviour as adaptation.

It is especially difficult to set quantitative boundaries to normal behaviour. One

should see it as being normal, that every dog being a beast of prey. will bite in some

situations. However, if it nearly always biteswhich means that the threshold of

irritation to bite is extremely lowthen the dog is disturbed in this aspect of its

behaviour. But where is the boundary? It is very difficult to say.

Another example: everyone knows that outside of batteries. hens scratch for food.

When we feed hens, they will scratch relatively little. This little scratching is obviously

42

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

not a behavioural disturbance, but rather an adaptation. Obviously the judgement in such

cases is highly dependent on how one defines the norm, and under which circumstances one accepts a norm.

It is easier to define a behavioural structure as a disturbance when it is a deviation

from the norm in a qualitative way, for example when it deviates from the norm in:

behaviour pattern, actions at non-adequate objects, actions without object vacuum

activity., and apathy.

Usually behavioural disturbances are equated with stereotypy. In English-speaking

countries especially, behavioural disorder and stereotypy are almost synonymous. I am

not happy with this definition. After all, movement characteristics of standard animal

behaviour, such as rumination and locomotion, are often stereotypical.

To further illustrate:

a. Cattle usually stand on the hind limbs first and then on the front. In boxes close to

the wall or when tethered too tightly the opposite occurs: the cattle stand up on their

front legs first and then on their hind.

b. When pigs get only a small amount of concentrates, then this is devoured quickly.

The animals are food satiated but they still have the urge for mouth activity.

Single-held pigs then demonstrate bar-biting.

c. Cattle on pasture are known to pull a clump of food into their mouth with their

tongues. When roughage is fed, for example corn silage, the tongue isnt used enough.

The animals then demonstrate tongue movements as a vacuum activity, which we call

tongue rolling.

d. Every behaviour pattern on the ethogram should be shown at least in special

situations, and there should be a recognisable specific activity. If this is not the case,

then it is also a deviation of the typical species behaviour. For example, hens do not

scratch for food in cages.

In some cases, even with great carefulness, we still cannot recognize whether specific

behaviour is a disturbance or an adaptation, meaning a somewhat significant act. Here I

especially think of food flinging. Some cows in the stable take the given fodder in their

mouth and toss it backwards with abrupt movement Fig. 1.. A part of the fodder thus

lands on the back of the animal. The majority, however, lands on the equipment of the

stable or on the ground. Often the slits in the slatted floor become filled and so lose their

drainage function.

We know there are differences between breeds with respect to this behaviour. The

amount of fodder flinging is higher in Brown Swiss than in Simmenthal cattle. We know

that this activity is strongly present at the beginning of the feeding, and then gradually

becomes less. We also know that this food-flinging activity is strongly correlated with

the frequency of eyelid beating. The frequency of eyelid beating is known to be an

indicator of an animals state of excitement Wittke and Bartsch, 1967.. Thus the

flinging of food could be associated with the level of excitement of the animal.

Owners try various things to stop this activity. For example, they place a halter on the

head of the animal with a sort of hammer on it Fig. 2.. Each time the animal flings its

head back, it is punished with a knock on the head. But whether this food-flinging is a

significant behaviour for the animal in any way, we still do not know.

Scientists have the urge to put everything in a system. This can be done in a

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

43

Fig. 1. Food flinging.

convenient way for behavioural disorders also. One can order them by functional circles,

thus grouping disturbances as: feeding behaviour, resting behaviour, and locomotion and

so forth.

In some cases the grouping can go one step further still. The feeding characteristics

can be subdivided into: food intake, preparation of fodder chewing., and swallowing.

There are behavioural disturbances in each of these three fields. As an example for

the assimilation of fodder, consider the previously mentioned tongue rolling of cows.

The behaviour also appears with giraffes, the only kind of mammal next to cattle who

use their tongues for food intake.

With respect to the preparation of the fodder, consider the empty chewing of the

breeding sow, which should be judged similarly to the bar-biting of single-kept sows.

For swallowing, consider cribbing of horses as a swallowing movement.

Behavioural disorders are significant for 2 reasons: they can have consequences we

do not wish, and they can have causes we do not wish. The consequences may be of the

economical kind, but they may also be animal-welfare problems. With respect to the

causes, we must always reckon that they are relevant to animal welfare. That is why one

should always try to treat these disorders of behaviour.

But this is where animal behaviour science reaches its limits. In former times, the

opinion was that the reasons for disorders were to be found in that functional circle

44

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

Fig. 2. Cow head with a halter.

from which the problem must have appeared. It is striking for example, that the most

disorders appear in those groups that have been most changed or reduced with farm

animals: feeding behaviour and locomotion.

Still we would say that behavioural disturbances only have their reason in the same

group of functional circles as where they appear. Feeding behaviour and locomotion are

2 very important functional circles for the animal. They are easily activated. It even

seems to be the case, that a frustration is easily manifested inside them.

Then, however, we have quickly reached the boundaries of behavioural science. The

search for the reasons becomes difficult. Let us take cannibalism among pigs. Due to the

pattern of movement, it is beyond doubt associated with feeding behaviour. However,

the reason for this disturbance seldom lies in feeding behaviour. Reasons could be: too

large groups, too high density of occupation, endo- or ectoparasites, breakdown of water

supply, irregular feeding, high levels of noise, or high concentration of poisonous gas in

the stables air NH 3 , H 2 S etc...

All these reasons have something in common, they excite the animals. The pigs thus

want to abrogate their excitement. In strawed stables, the available straw is used. In

stables with a slatted floor and therefore no bedding, this abreaction occurs towards a

next of kin Fig. 3..

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

45

Fig. 3. An extreme case of cannibalism in pigs.

Naturally, the causes referred to and the example of the slatted floor are exogenous

factors and must, hence, be categorised as releasers in the ethologists eyes. But there

are further factors: cannibalism did not occur with earlier types of swine, being the more

phlegmatic old type of lard hog, but instead with the more modern meat hog. And

female animals are more affected than castrates.

Thus endogenous components are also present. The endogenous components are

surely also present with many other kinds of behaviour disorders. In the past, one

reckoned that some substance was missing in the fodder if the animal showed some

abnormality in its feeding behaviour. This is surely wrong. A reality is that reactionary

behavioural disorders, being caused by the conditions of husbandry, is only one of

several categories of disturbance.

2. Ethology and analogy in assessment of animal suffering

It has become clear over recent years that of all scientific disciplines, behavioural

science has the strongest bond with animal protection. Based on existing morphological

and physiological factors, one can obviously accept the relevance of animal protection,

but the ethologists feel particularly responsible for it. This is a risky business. Firstly,

until recently, while always caring for the well-being of the animals, many veterinarians

felt that the striving for animal protection quickly went too far. The second restriction

will be explained hereinafter.

The difficulty lies in the essence of animal protection. All things against which we try

to protect the animals are sensations: pain, suffering, fear, hunger, thirst, etc. Actual

damages are often associated with these, but only those which are allied with pain and

suffering. Damaged fur or plumage of an exhibition animal can be viewed as damage to

its owner, but no one would ever consider such damage in the context of animal welfare.

46

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

We can prove none of the sensations named above. But we cannot deny that animals

can have negative, animal-protection-related sensations. Animal protection is always

sensation protection.

The exercise now is the search for sensation indicators. What must be particularly

stressed is the fact that we can no more than indicate the indicators. From these

indicators, we must suspect pain, suffering, fear, etc.

This is surely an exceptional procedure in science, moving away from the usually

procedures of exact science. This method is subject to much criticism. And as this

method is mainly used by ethologists, they are observed most critically. To avoid

misunderstandings: not the seizing of objective criteria is being criticized, but rather the

subsequent conclusion regarding sensations. But this cannot be avoided, asI repeat

animal protection only deals with sensations.

A recent publication Hemsworth et al., 1995. begins as follows: The problem in

objectively assessing welfare from any standpoint is the inherent inadequacy of the

abstract concept of welfare. This problem is difficult to solve when definitions of

welfare include well-being, suffering or other subjective feelings.

I say in reply to this: animal protection is only affected when dealing with the

well-being, suffering, pain or other subjective feelings. Animal protection is sensation

protection, nothing else.

It is impossible to methodically objectivise sensations. Sometimes we must delay

solving problems regarding animal protection until methods are found to objectively

evaluate sensations. This must be contradicted by saying that such is scientifically

impossible. Sensations are bonded to the individual. All that we can measure and count

may be correlated with feelings like pain, well-being or suffering, but it is neer the

actual sensation itself.

Where we cannot record the animals sensations, how can we assume that animals

possess sensation at all? The answer is: by the analogy-conclusion of mankind Sambraus,

1981, 1995..

The following happens in this respect: it is heard from time to time that research is

not advanced enough to portray sensation. If more exact instruments for measurement

were available, one could probably be more precise about it, because the sensation could

be registered directly. The problem then becomes a scientific-theoretical question. Of

course one could measure accompanying phenomenons even more precisely but such

would be completely superfluous.. But sensations can only be perceived by the

individual itself. They are not measurable and never will be.

There is another aspect in this context: every person should be ethically obliged to be

confronted with animals sensation. Due to his job, this aspect is particularly relevant for

the veterinarian, because in Germany, through the Federal license to practice for

veterinarians, every certified veterinarian is appointed, to presere the animals from,

reliee them and to heal them of suffering and illness. If veterinary medicine takes its

responsibility seriously, and there is no doubt it does, then it must find a way to make

suffering thus sensations. recognizable. As a matter of fact, every veterinarian does this

daily in hisrher practice. It also applies to responsible owners of animals. It is just that

sensations are not consciously ascertained, but rather noticed through indications.

Now every person knows feelings of most distinct kinds. He knows how it is to feel

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

47

pain. He knows fear, he has been dizzy before and he has felt hunger or thirst or cold.

Each human being knows his own reactions towards such sensations. The scientist, and

not only him, can discover through verbal contact, that such feelings are not unique to

himself, but occur in others as well.

When animals scream and shiver in some situation, when they have widely opened

eyes and have profuse perspiration, then there can be no doubt that they have sensations.

This conclusion becomes even more plausible when we realize that the sensation is

biologically useful, even an absolute necessity.

To make it clear again; the conclusion of analogy means the following: 1. Man has

sensations. He feels pain, hunger and thirst, and knows fear and nausea. 2. Such

sensations are accompanied by objectively observable accompanying phenomena. They

can be the cause of the sensation, for example, an injury when in pain or an intensive

search for food when hungry. In some cases physiological changes are demonstrable,

like a low level of sugar in the blood or high levels of adrenalin. 3. Deviations from the

morphological, physiological and ethological norm are also known with animals.

Furthermore, it can be proved that these distortions appear in distinct situations. 4. Thus

one can assume the presence of sensations. It is a conclusion in which man plays a

leading role.

To avoid misunderstandings, one thing must be stressed here: this is not about a

trivial analogy, e.g., because I do not want to spend the night on a pole, a hen does not

get one either. Of course the species-specific and natural behaviour of the animals are

taken into consideration. The conclusion of analogy only relates to very basic biological

phenomenon. The aim here in no way is a humanization of the animals.

Basically, the conclusion of analogy is something very general and usual. It is

imaginable that animal protection is traditioned in some aspects and happens unconsciously. Someone who has studied veterinary medicine, zoology or agriculture must

learn where to set his limits in distinct situations, and how to notice where these limits

are, for the protection of the animal. But he wont get very far with this knowledge, as

the problems are too diverse.

It is apparent that everyone, mostly unintentionally and unconsciously, uses analogy

to answer questions of animal protection. Thus, we recognize that the cries of an animal

are noted as pain and widely opened eyes are noted as fear. The examples in this paper

should have made clear that these reactions of the animals can be clear indications of

pain; but they are still no more than symptoms.

To use analogy in questions of animal welfare is not new. Thirty years ago the

Report of the Technical Committee to Inquire into the Welfare of Animals kept under

Intensive Livestock Husbandry Systems was created in Great Britain better known

under the name Brambell Report.. In chapter 4 of this report the following was

written: Nobody can experience the feelings of another individual, however well that

person may be known to them. They can be evaluated only by analogy with ones own

feelings, from what that person tells us, and from ones own observation of his looks,

behaviour, and health. The evaluation of the feelings of an animal similarly must rest on

analogy with our own and must be derived from observation of the cries, expressions,

reactions, behaviour, health and productivity of the animal.

Analogies can be made in anatomy, physiology and ethology. The analogy of

48

H.H. Sambrausr Applied Animal Behaiour Science 59 (1998) 3948

behaviour is recognized most easily, and is most understandable for the layman. So,

concerning problems in animal protection, the ethologist must stress and interpret the

ethological peculiarities, even if he is risking being seen as unscientific in doing so.

The partly insecure assertions of ethology are products of the modest research

intensity in this scientific discipline. More exact, and more numerous results can only be

expected, if the subject applied ethology becomes a more significant one at all colleges

of veterinarian medicine. This would also have a positive effect on the study and thus

knowledge of the practicing veterinarian.

References

Hemsworth, P.H., Barnett, J.L., Beverdige, L., Matthews, L.R., 1995. The welfare of extensively managed

dairy cattle: a review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 42, 161182.

Sambraus, H.H., 1981. Tierschutz, Tierhaltung und Tierarzt Dtsch. Tierarzteblatt

29:252262, 342346.

Sambraus, H.H., 1995. Befindlichkeiten und Analogieschlu. KTBL-Schrift 370, 3139.

Wittke, G., Bartsch, W., 1967. Der Lidschlag als Erregungs-symptom beim Rinde. Zbl. Vet. Med. A. 14,

222229.

Você também pode gostar

- Diagnosis of Welfare in CattleDocumento10 páginasDiagnosis of Welfare in CattleJULIANA PAOLA MARTINEZ ACUÑAAinda não há avaliações

- Social Predation: How Group Living Benefits Predators and PreyNo EverandSocial Predation: How Group Living Benefits Predators and PreyAinda não há avaliações

- Animal HappyDocumento9 páginasAnimal HappyTô Yến VyAinda não há avaliações

- 1.4 Components of Ethology: InstinctDocumento7 páginas1.4 Components of Ethology: InstinctAndreea BradAinda não há avaliações

- Veterinary Ethics - Case Studies - Animals As Tools - Frank BuschDocumento2 páginasVeterinary Ethics - Case Studies - Animals As Tools - Frank BuschFrank BuschAinda não há avaliações

- 1xx - Parte LibroDocumento4 páginas1xx - Parte LibroKat Jara VargasAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Behaviour 2Documento17 páginasAnimal Behaviour 2OwodunniOluwatosinTaofeekAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Conceptos Basicos Alimentacion PDFDocumento5 páginas1 Conceptos Basicos Alimentacion PDFLauraMercadoIzquierdoAinda não há avaliações

- Depression in Caged Animals: A Study at The National Zoo, Kuala Lumpur, MalaysiaDocumento12 páginasDepression in Caged Animals: A Study at The National Zoo, Kuala Lumpur, MalaysiaSilvina PezzettaAinda não há avaliações

- Efficient Livestock Handling: The Practical Application of Animal Welfare and Behavioral ScienceNo EverandEfficient Livestock Handling: The Practical Application of Animal Welfare and Behavioral ScienceAinda não há avaliações

- EMRA™ Intelligence: The revolutionary new approach to treating behaviour problems in dogsNo EverandEMRA™ Intelligence: The revolutionary new approach to treating behaviour problems in dogsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (2)

- The Welfare of DogsDocumento287 páginasThe Welfare of Dogspatrysib100% (3)

- JK Black Shaw Whole BookDocumento102 páginasJK Black Shaw Whole BookMartha Isabel100% (1)

- ETHICSDocumento4 páginasETHICSKristine MangilogAinda não há avaliações

- The Waltham Book of Human-Animal Interaction: Benefits and Responsibilities of Pet OwnershipNo EverandThe Waltham Book of Human-Animal Interaction: Benefits and Responsibilities of Pet OwnershipI. RobinsonAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Research Ethics DilemmaDocumento4 páginasAnimal Research Ethics DilemmaSergiu MindruAinda não há avaliações

- Slide Presentation of Bioethical Issues Concerning Animal Testing in ResearchDocumento17 páginasSlide Presentation of Bioethical Issues Concerning Animal Testing in ResearchCt Shahirah100% (1)

- Geriatric Feline MedicineDocumento9 páginasGeriatric Feline Medicineapi-27393094Ainda não há avaliações

- 50 Homeopathic First-Aid Medicines for Animals: Benefits and UsesNo Everand50 Homeopathic First-Aid Medicines for Animals: Benefits and UsesAinda não há avaliações

- SSRR Studyguide Las1006216-Def-website v2Documento15 páginasSSRR Studyguide Las1006216-Def-website v2Ulises VictoriaAinda não há avaliações

- Fraser 2003. AW Science and ValuesDocumento11 páginasFraser 2003. AW Science and ValuesMonica ListAinda não há avaliações

- Euthanasia of Experimental AnimalsDocumento24 páginasEuthanasia of Experimental AnimalsAkhmad PanduAinda não há avaliações

- Homeopathic First Aid for Domestic Fowl: Accidents, Emergencies and Common AilmentsNo EverandHomeopathic First Aid for Domestic Fowl: Accidents, Emergencies and Common AilmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Concepts in Animal Welfare'': A Syllabus in Animal Welfare Science and Ethics For Veterinary SchoolsDocumento3 páginasConcepts in Animal Welfare'': A Syllabus in Animal Welfare Science and Ethics For Veterinary SchoolsGINA ALEXANDRA VELÁSQUEZ SÁNCHEZAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Vigilance: Monitoring Predators and CompetitorsNo EverandAnimal Vigilance: Monitoring Predators and CompetitorsAinda não há avaliações

- Swiss ethics guidelines for animal experimentsDocumento6 páginasSwiss ethics guidelines for animal experimentsBibhu PandaAinda não há avaliações

- TM-4 Use of Animals in Research and EducationDocumento37 páginasTM-4 Use of Animals in Research and EducationAnita Maulinda Noor100% (1)

- Care and Handling of Experimental AnimalDocumento1 páginaCare and Handling of Experimental AnimalDebashis ChaudhuriAinda não há avaliações

- M1 SA Introduction To Animal WelfareDocumento4 páginasM1 SA Introduction To Animal Welfarefsuarez113Ainda não há avaliações

- What Is Animal Behavior?: College Teaching and Research - Most Animal Behaviorists Teach And/or Do IndependentDocumento3 páginasWhat Is Animal Behavior?: College Teaching and Research - Most Animal Behaviorists Teach And/or Do IndependentChole LeAinda não há avaliações

- Hayvan HaklarıDocumento19 páginasHayvan HaklarıAyşe Menteş GürlerAinda não há avaliações

- Canine Atopy and How to Reboot Your Allergic Dog's HealthNo EverandCanine Atopy and How to Reboot Your Allergic Dog's HealthAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Rights PaperDocumento8 páginasAnimal Rights PaperDawn OwensAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Training and ImplicationsDocumento12 páginasAnimal Training and ImplicationsBarbaraAinda não há avaliações

- Final PaperDocumento4 páginasFinal PaperHarsh BhatoaAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Animal WelfareDocumento14 páginasIntroduction To Animal WelfareALYANA RAMONETE ACERAAinda não há avaliações

- Homeopathic First-Aid for Horses & Ponies : Emergencies and Common AilmentsNo EverandHomeopathic First-Aid for Horses & Ponies : Emergencies and Common AilmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Animals Make Us Human: Creating the Best Life for AnimalsNo EverandAnimals Make Us Human: Creating the Best Life for AnimalsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (221)

- M1 LN Introduction To Animal WelfareDocumento14 páginasM1 LN Introduction To Animal Welfarefsuarez113100% (1)

- Animal ModelsDocumento21 páginasAnimal ModelsSudarshan UpadhyayAinda não há avaliações

- The Welfare of CatsDocumento297 páginasThe Welfare of CatsVanessa Versiani100% (1)

- Module 1 Introduction To Pet PsychologyDocumento7 páginasModule 1 Introduction To Pet Psychologyk.magdziarczykAinda não há avaliações

- The Exotic Pet Consultation: History TakingDocumento3 páginasThe Exotic Pet Consultation: History TakingDavid PGAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Animal ResearchDocumento10 páginas3 Animal ResearchMaelAinda não há avaliações

- Cell Organism Stimulation Species Natural Selection VariationDocumento1 páginaCell Organism Stimulation Species Natural Selection VariationZhalliaAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture-7: Ethics in Animal Subjects: Sherif H. El-Gohary, PHDDocumento40 páginasLecture-7: Ethics in Animal Subjects: Sherif H. El-Gohary, PHDMustafa EliwaAinda não há avaliações

- Animal ExperimentationDocumento80 páginasAnimal Experimentationडा. सत्यदेव त्यागी आर्य100% (3)

- Don't Have The Wool Pulled Over Your Eyes: Humane Society of The United States As Their Stated GoalDocumento4 páginasDon't Have The Wool Pulled Over Your Eyes: Humane Society of The United States As Their Stated GoalMariana FelippeAinda não há avaliações

- ContoversiesDocumento6 páginasContoversiesMolly CrombieAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Behaviour WDocumento154 páginasAnimal Behaviour Wdawitdafe4Ainda não há avaliações

- Title: Healing Paws and Feathers: A Comprehensive Exploration of A Career in Veterinary MedicineDocumento3 páginasTitle: Healing Paws and Feathers: A Comprehensive Exploration of A Career in Veterinary MedicineDelia Maria VisanAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Main Characteristics of AnimalsDocumento4 páginas5 Main Characteristics of AnimalsHildegard HallasgoAinda não há avaliações

- Animal ResearchDocumento4 páginasAnimal Researchikitan20050850Ainda não há avaliações

- Experimental PharmacologyDocumento70 páginasExperimental PharmacologyPhysiology by Dr Raghuveer90% (77)

- Animal Welfare CourseDocumento42 páginasAnimal Welfare CourseDr-Rmz RabadiAinda não há avaliações

- EthologyDocumento6 páginasEthologyDheeraj K VeeranagoudarAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Research Essay ThesisDocumento8 páginasAnimal Research Essay Thesiskatieboothwilmington100% (2)

- Veterinarians Rough DraftDocumento3 páginasVeterinarians Rough Draftapi-213776337Ainda não há avaliações

- Oet Writing Exercise AnswersDocumento10 páginasOet Writing Exercise AnswersLia Angulo-Estrada95% (22)

- Student Materia MedicaDocumento9 páginasStudent Materia Medicaa_j_sanyal259Ainda não há avaliações

- Care Plan #1 - June 2012Documento4 páginasCare Plan #1 - June 2012Meghan Equality ShalvoyAinda não há avaliações

- Puji Nur Khasanah BAB IIDocumento4 páginasPuji Nur Khasanah BAB IIWindhy HaningAinda não há avaliações

- Penn Shoulder Score 3Documento2 páginasPenn Shoulder Score 3Izemari SwartAinda não há avaliações

- Theories of Pain - From Specificity To Gate Control - 2013Documento8 páginasTheories of Pain - From Specificity To Gate Control - 2013Angelica RamirezAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Pain Nursing Care PlanDocumento3 páginasAcute Pain Nursing Care PlanTipey Segismundo100% (1)

- Staged Approach For Rehabilitation ClassificationDocumento10 páginasStaged Approach For Rehabilitation ClassificationCambriaChicoAinda não há avaliações

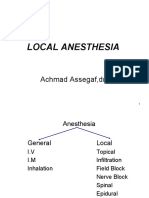

- Local Anesthesia: Achmad Assegaf, DR., SP - AnDocumento48 páginasLocal Anesthesia: Achmad Assegaf, DR., SP - AnDesty ArianiAinda não há avaliações

- Focus On Diagnosis of Acute Compartment Syndrome PDFDocumento8 páginasFocus On Diagnosis of Acute Compartment Syndrome PDFMuthia DewiAinda não há avaliações

- Difficult Patient Encounters: Assessing Pediatric Residents' Communication Skills Training NeedsDocumento19 páginasDifficult Patient Encounters: Assessing Pediatric Residents' Communication Skills Training NeedsJesse M. MassieAinda não há avaliações

- Led Light Therapy GuideDocumento23 páginasLed Light Therapy GuidePeter Freimann100% (4)

- How Do Magnets WorkDocumento9 páginasHow Do Magnets WorkDelAinda não há avaliações

- Pediatrics Nursing L5Documento89 páginasPediatrics Nursing L5MaxAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of Cancer RehabilitationDocumento22 páginasThe Role of Cancer RehabilitationLizeth ArceAinda não há avaliações

- TSU Nursing Performance Evaluation ChecklistDocumento7 páginasTSU Nursing Performance Evaluation ChecklistKatKat Bognot100% (2)

- Pain RehabilitationDocumento34 páginasPain RehabilitationHusnul MubarakAinda não há avaliações

- Dutton Chapter 11 Manual TherapiesDocumento24 páginasDutton Chapter 11 Manual Therapiesmaria_dani100% (1)

- Shawa - Patients Perceptions Regarding Nursing Care in The General Surgical Wards at Kenyatta National Hospital - NinisannnDocumento103 páginasShawa - Patients Perceptions Regarding Nursing Care in The General Surgical Wards at Kenyatta National Hospital - Ninisannnnoronisa talusobAinda não há avaliações

- Healing With The Arts - ExcerptDocumento28 páginasHealing With The Arts - ExcerptBeyond Words Publishing100% (7)

- Cauze Emotionale Boli Louise HayDocumento10 páginasCauze Emotionale Boli Louise Haymarimira_2004Ainda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Hypnosis Knowledge Among Dentists: A Cross Sectional StudDocumento9 páginasAssessment of Hypnosis Knowledge Among Dentists: A Cross Sectional StudSri Mulyani DjunaidiAinda não há avaliações

- POS Questionnaire v1 Patient EN-22-08-2011Documento2 páginasPOS Questionnaire v1 Patient EN-22-08-2011StefiSundaranAinda não há avaliações

- Iabetic Europathy: DR Saumya H Mittal Neurologist Sharda Hospital & Health CityDocumento39 páginasIabetic Europathy: DR Saumya H Mittal Neurologist Sharda Hospital & Health CityGhea SugihartiAinda não há avaliações

- Nejmcp 2032396Documento10 páginasNejmcp 2032396juan carlosAinda não há avaliações

- How To Write A SOAP Note-3-10Documento2 páginasHow To Write A SOAP Note-3-10mohamed_musaferAinda não há avaliações

- Cause Effect ParagraphDocumento4 páginasCause Effect ParagraphZineb AmelAinda não há avaliações

- Physiological Mechanisms of PainDocumento7 páginasPhysiological Mechanisms of PainZAFFAR QURESHIAinda não há avaliações

- NCP Chronic PainDocumento4 páginasNCP Chronic Painkentkrizia100% (3)

- Transcutaneous Nerve StimulationDocumento6 páginasTranscutaneous Nerve StimulationARGAinda não há avaliações