Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Essays

Enviado por

Kimberly NgDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Essays

Enviado por

Kimberly NgDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

of ancient Malacaang Palace, in the symbolic

act of possession and racial vindication.

I Am A Filipino by Carlos Romulo

I am a Filipino,

I am a Filipino - inheritor of a glorious past,

hostage to the uncertain future. As such I must

prove equal to a two-fold task- the task of

meeting my responsibility to the past, and the

task of performing my obligation to the future.

I sprung from a hardy race - child of many

generations removed of ancient Malayan

pioneers. Across the centuries, the memory

comes rushing back to me: of brown-skinned

men putting out to sea in ships that were as frail

as their hearts were stout. Over the sea I see

them come, borne upon the billowing wave and

the whistling wind, carried upon the mighty

swell of hope- hope in the free abundance of

new land that was to be their home and their

children's forever.

This is the land they sought and found. Every

inch of shore that their eyes first set upon,

every hill and mountain that beckoned to them

with a green and purple invitation, every mile of

rolling plain that their view encompassed, every

river and lake that promise a plentiful living and

the fruitfulness of commerce, is a hollowed spot

to me.

By the strength of their hearts and hands, by

every right of law, human and divine, this land

and all the appurtenances thereof - the black

and fertile soil, the seas and lakes and rivers

teeming with fish, the forests with their

inexhaustible wealth in wild life and timber, the

mountains with their bowels swollen with

minerals - the whole of this rich and happy land

has been, for centuries without number, the

land of my fathers. This land I received in trust

from them and in trust will pass it to my

children, and so on until the world no more.

I am a Filipino. In my blood runs the immortal

seed of heroes - seed that flowered down the

centuries in deeds of courage and defiance. In

my veins yet pulses the same hot blood that

sent Lapulapu to battle against the alien foe

that drove Diego Silang and Dagohoy into

rebellion against the foreign oppressor.

That seed is immortal. It is the self-same seed

that flowered in the heart of Jose Rizal that

morning in Bagumbayan when a volley of shots

put an end to all that was mortal of him and

made his spirit deathless forever; the same that

flowered in the hearts of Bonifacio in

Balintawak, of Gergorio del Pilar at Tirad Pass,

of Antonio Luna at Calumpit; that bloomed in

flowers of frustration in the sad heart of Emilio

Aguinaldo at Palanan, and yet burst fourth

royally again in the proud heart of Manuel L.

Quezon when he stood at last on the threshold

The seed I bear within me is an immortal seed.

It is the mark of my manhood, the symbol of

dignity as a human being. Like the seeds that

were once buried in the tomb of Tutankhamen

many thousand years ago, it shall grow and

flower and bear fruit again. It is the insigne of

my race, and my generation is but a stage in

the unending search of my people for freedom

and happiness.

I am a Filipino, child of the marriage of the East

and the West. The East, with its languor and

mysticism, its passivity and endurance, was my

mother, and my sire was the West that came

thundering across the seas with the Cross and

Sword and the Machine. I am of the East, an

eager participant in its struggles for liberation

from the imperialist yoke. But I also know that

the East must awake from its centuried sleep,

shape of the lethargy that has bound his limbs,

and start moving where destiny awaits.

For, I, too, am of the West, and the vigorous

peoples of the West have destroyed forever the

peace and quiet that once were ours. I can no

longer live, being apart from those world now

trembles to the roar of bomb and cannon shot.

For no man and no nation is an island, but a

part of the main, there is no longer any East

and West - only individuals and nations making

those momentous choices that are hinges upon

which history resolves.

At the vanguard of progress in this part of the

world I stand - a forlorn figure in the eyes of

some, but not one defeated and lost. For

through the thick, interlacing branches of habit

and custom above me I have seen the light of

the sun, and I know that it is good. I have seen

the light of justice and equality and freedom and

my heart has been lifted by the vision of

democracy, and I shall not rest until my land

and my people shall have been blessed by

these, beyond the power of any man or nation

to subvert or destroy.

I am a Filipino, and this is my inheritance. What

pledge shall I give that I may prove worthy of

my inheritance? I shall give the pledge that has

come ringing down the corridors of the

centuries, and it shall be compounded of the

joyous cries of my Malayan forebears when

they first saw the contours of this land loom

before their eyes, of the battle cries that have

resounded in every field of combat from Mactan

to Tirad pass, of the voices of my people when

they sing:

Land of the Morning,Child of the sun

returning...Ne'er shall invadersTrample thy

sacred shore.

Out of the lush green of these seven thousand

isles, out of the heartstrings of sixteen million

people all vibrating to one song, I shall weave

the mighty fabric of my pledge. Out of the songs

of the farmers at sunrise when they go to labor

in the fields; out of the sweat of the hard-bitten

pioneers in Mal-ig and Koronadal; out of the

silent endurance of stevedores at the piers and

the ominous grumbling of peasants Pampanga;

out of the first cries of babies newly born and

the lullabies that mothers sing; out of the

crashing of gears and the whine of turbines in

the factories; out of the crunch of ploughs

upturning the earth; out of the limitless patience

of teachers in the classrooms and doctors in the

clinics; out of the tramp of soldiers marching, I

shall make the pattern of my pledge:

"I am a Filipino born of freedom and I shall not

rest until freedom shall have been added unto

my inheritance - for myself and my children's

children - forever.

A Letter To His Parents by Jose Rizal

My dear Parents, Brothers, and Sisters:

The love I have always borne you

dictates the step I am about to take. Only the

future will show whether it is well and wisely

taken or not. Whatever may be the result, it

can, it should be said that it was my sense of

duty that forced me to act. Should I perish in

what I contemplate doing, that will make, should

make, no difference.

I know I have caused you one and all

to suffer match, but I do not repent having done

so; and should it be given me to begin my life

all over again, I would not change my conduct.

It has all been inspired by my appreciation of

my duty. I am starting now, and gladly, to

expose myself to perils and to the dangers that

may be awaiting me, not as an expiation of my

faults, for in this direction at least I do not think I

have committed any, but I am going to crown

my work, to bear witness by personal example,

to the truth of that which I have always

preached.

A man should die for his convictions

and in the performance of his duty as he sees

it. I beg you to believe that I still maintain all the

ideas which I have proclaimed in regard to the

present state and the future of my country; and

I shall gladly die for my country more gladly

still if I might thereby secure for you all the

justice and tranquility which has been wanting.

It is indeed with pleasure that I risk my

life to save so many innocents, so many

nephews and nieces, to safeguard the children

of friends as well as the children of those who

are not my friends but who have been or are

now suffering for me. For what am I? Alone,

single man almost without family and quite

without illusions as to life. I have suffered many

deceptions, and what the future has in store for

me is obscure; and it would be still more

obscure were it not illuminated by the dawning

light, the aurora of my fatherland.

Jose Rizal

Inertia, I suppose, and the sort of reality we

moderns know make falling in love with my

immediate neighbors often a matter of severe

strain and effort to me.

The World in a Train

Francisco B. Icasiano

One Sunday I entrained for Baliwag, a town in

Bulacan which can well afford to hold two

fiestas a year without a qualm.

Let me give a sketchy picture of the little world

whose company Mang Kiko shared in moments

which soon passed away affecting most of us.

I took the train partly because I am prejudiced

in favor of the government-owned railroad,

partly because I am allowed comparative

comfort in a coach, and finally because trains

sometimes leave and arrive according to

schedule.

First, there came to my notice three husky

individuals who dusted their seats furiously with

their handkerchiefs without regard to hygiene or

the brotherhood of men. It gave me no little

annoyance that on such a quiet morning the

unpleasant aspects in other people's ways

should claim my attention.

In the coach I found a little world, a section of

the abstraction called humanity whom we are

supposed to love and live for. I had previously

arranged to divide the idle hour or so between

cultivating my neglected Christianity and

smoothing out the rough edges of my nature

with the aid of grateful sights without - the

rolling wheels, the flying huts and trees and

light-green palay seedlings and carabaos along

the way.

Then there was a harmless-looking middleaged man in green camisa de chino with rolled

sleeves who must have entered asleep. When I

noticed him he was already snugly entrenched

in a corner seat, with his slippered feet

comfortably planted on the opposite seat, all the

while his head danced and dangled with the

motion of the train. I could not, for the love of

me, imagine how he would look if he were

awake.

A child of six in the next seat must have shared

with me in speculating about the dreams of this

sleeping man in green. Was he dreaming of the

Second World War or the price of eggs? Had he

any worries about the permanent dominion

status or the final outcome of the struggles of

the masses, or was it merely the arrangement

of the scales on a fighting roaster's legs that

brought that frown on his face?

But the party that most engaged my attention

was a family of eight composed of a short but

efficient father, four very young children,

mother, grandmother, and another woman who

must have been the efficient father's sister.

They distributed themselves on four benches you know the kind of seats facing each other so

that half the passengers travel backward. The

more I looked at the short but young and

efficient father the shorter his parts looked to

me. His movements were fast and short, too.

He removed his coat, folded it carefully and

slung it on the back of his seat. Then he pulled

out his wallet from the hip pocket and counted

his money while his wife and the rest of his

group watched the ritual without a word.

Then the short, young, and efficient father stood

up and pulled out two banana leaf bundles from

a bamboo basket and spread out both bundles

on one bench and log luncheon was ready at

ten o'clock. With the efficient father leading the

charge, the children (except the baby in his

grandmother's arms) began to dig away with

little encouragement and aid from the elders. In

a short while the skirmish was over, the enemy shrimps, omelet, rice and tomato sauce - were

routed out, save for a few shrimps and some

rice left for the grandmother to handle in her

own style later.

Then came the water-fetching ritual. The father,

with a glass in hand, led the march to the train

faucet, followed by three children whose faces

still showed the marks of a hard-fought-battle.

In passing between me and a person, then

engaged in a casual conversation with me, the

short but efficient father made a courteous

gesture which is still good to see in these

democratic days; he bent from the hips and,

dropping both hands, made an opening in the

air between my collocutor and me - a gesture

which in unspoiled places means "Excuse Me."

In one of the stations where the train stopped, a

bent old woman in black

boarded the train. As it moved away, the old

woman went about the coach,

begging holding every prospective Samaritan

by the arm, and stretching forth her

gnarled hand in the familiar fashion so

distasteful to me at that time. There is

something in begging which destroys some

fiber in most men. "Every time you

drop a penny into a beggar's palm you help

degrade a man and make it more

difficult for him to rise with dignity. . ."

There was something in his beggar's eye which

seemed to demand. "Now do

your duty." And I did. Willy-nilly I dropped a coin

and thereby filled my life with

repulsion. Is this Christianity? "Blessed are the

poor . . ." But with what speed did

that bent old woman cross the platform into the

next coach!

While thus engaged in unwholesome thought, I

felt myself jerked as the train made a curve to

the right. The toddler of the family of eight lost

his balance and caught the short but efficient

father off-guard. In an instant all his efficiency

was

employed in collecting the shrieking toddler

from under his seat. The child had, in

no time, developed two elongated bumps on

the head, upon which was applied a

moist piece of cloth. There were no reproaches,

no words spoken. The discipline

in the family was remarkable, or was it because

they considered the head as a

minor anatomical appendage and was therefore

nor worth the fuss?

Occasionally, when the child's crying rose

above the din of the locomotive and

the clinkety-clank of the wheels on the rails, the

father would jog about a bit without

blushing, look at the bumps on his child's head,

shake his own, and move his lips

saying, "Tsk, Tsk." And nothing more.

Fairly tired of assuming the minor

responsibilities of my neighbors in this little

world in motion, I looked into the distant horizon

where the blue Cordilleras merged

into the blue of the sky. There I rested my

thoughts upon the billowing silver and grey

of the clouds, lightly remarking upon their being

a trial to us, although they may not

know it. We each would mind our own business

and suffer in silence for the littlest

mistakes of others; laughing at their ways if we

happened to be in a position to suspend our

emotion and view the whole scene as a god

would; or, we could weep for other men if we

are the mood to shed copious tears over the

whole tragic aspect of a world thrown out of

joint.

It is strange how human sympathy operates.

We assume an attitude of complete

indifference to utter strangers whom we have

seen but not met. We claim that they are the

hardest to fall in love with in the normal exercise

of Christian charity. Then a little child falls from

a seat, or a beggar stretches forth a gnarled

hand, or three husky men dust their seats; and

we are, despite our pretensions, affected. Why

not? If even a sleeping man who does nothing

touches our life!

hard on the back. Looking behind, I saw my

father. He was annoyed because I had

disturbed his siesta. I picked up a pillow at my

feet, gave it to him, and went back to our mat.

The two other children were fast asleep. The

sight of the whip, symbol of parental authority,

hanging on the posts, gave me no other choice

but to lie down.

The ayuntamiento of Manila or the commander

of the regiment in Intramuros did well in

ordering the closing of the gates during the

siesta hour. Once, the Chinese living in Parian,

just a short way from the Walled City, timed the

beginning of one of their revolts by attacking at

two o'clock in the afternoon. They were sure

that the dons, including the guards and

sentinels, were having their siesta. They felt

that they would be more successful if the attack

came at siesta time.

Siesta

Leopoldo Serrano

When I was a boy, one of the rules at home that

I did not like at all was to be made to lie on the

bare floor of our sala after lunch. I usually lay

side by side with two other children in the

family. We were forced to sleep by my mother.

She watched us as we darned old dresses,

read an awit, or hammed a cradle song in

Tagalog.

She always reminded us that sleeping at noon

enables children to grow fast like the grass in

our yard. In this way, in most Filipino homes

many years ago, children made to understand

what the siesta was. Very often I had to pretend

to be asleep by closing my eyes.

Once while my mother was away, I tries to

sneak out of the house during the siesta hour. I

had not gone far when I felt something hit me

During my childhood, whenever we had house

guests, my mother never failed to put mats and

pillows on the floor of our living room after the

noonday meal. Then she would invite our

guests to have their siesta. Hospitality and good

taste demanded that this be not overlooked.

The custom of having a siesta was introduces

in our country by the Spaniards. Indee, during

the Spanish times, the Philippines was the land

of the fiesta the novena, and the siesta.

Many foreigners have noted this custom among

our people. Some believe that even the guards

at the gates of Intramuros had their siesta. It

was a commonly known fact that every

afternoon the gates of the city were closed for

fear of a surprise attack.

Even today visits to Filipino homes are not

usually made between one o'clock and two

o'clock in the afternoon. It is presumed that the

people in the house are having their siesta. It is

not polite to have them awakened from their

noonday nap to accommodate visitors. There is

well-known saying believed by many of our

people: "You may joke with a drunkard but not

one who has been disturbed during his siesta."

Our custom of having our siesta has not been

greatly affected by American influence. We

have not learned the Yankee's bustle and

eagerness of endurance for continuous work

throughout the day.

But if only for its health -giving effects, we

should be grateful to the Spaniards for the

siesta, especially during the hot weather, for the

siesta serves to restore the energy lost while

working under a hot climate.

as they delighted the palate. Here, the papaya

stretched out its broad leaves and tempted the

birds with its enormous fruit; there the langka,

the coffee and the orange trees perfumed the

air with the aroma of their flowers. On this side

is the iba, , thebalimbing, the pomegranate with

its abundant foliage and its lovely flowers

bewitched the senses; while here and there

rose the majestic palm trees loaded with huge

nuts, swaying their proud tops and graceful

branches, queens of the forests. I should never

end where I to number all our trees and amuse

myself identifying them.

panorama of twilight, thoughts that are long

gone renew them with nostalgic eagerness.

Came then the night to unfold her mantle,

somber at times, for all its stars, when the

chaste Diana failed to course through the sky in

pursuit of her brother Apollo. But when she

appeared, a vague brightness was to be

discerned in the clouds; then seemingly they

would crumble; and little she was to be seen,

lovely, grave, and silent, rising like an immense

globe which an invisible and omnipotent hand

drew through space.

My Home

Dr. Jose Rizal

I have nine sisters and one brother. My father, a

model of fathers, had given us and education in

proportion to our modest means. By dint of

frugality, he was able to build a stone house, to

buy another, and to raise a small nipa hut in the

midst of a groove we had, under the shade of

the banana and other trees.

There the delicious atis displayed its delicate

fruit and lowered its branches as if to save me

from trouble of reaching out for them. The

sweet santol, the scented and mellow tampoy,

the pink makopa vie for my favor. Farther away,

the plum tree, the harsh but flavorous casuy,

the beautiful tamarind pleases the eye as much

In the twilight, innumerable birds gathered from

everywhere and I, a child of three years at

most, amused myself watching them with

wonder and joy. The yellow kuliawan, themaya

in all its varieties, the kulae, the maria karpa,

the martin, all the species of pipitjoined the

pleasant harmony and raised in varied chorus a

farewell hymn to the sun as it vanished behind

the tall mountains of my town.

Then the clouds, through a caprice of nature,

combined in a thousand shapes, which would

suddenly dissolve, leaving me with only the

slightest recollections. Even now, when I look

out of the window of our house at a splendid

At such time, my mother gathered us all

together to say the rosary. Afterward, we would

go to the azotea or to some window where the

moon could be seen, and my ayah would tell us

stories, sometimes lugubrious and at other

times gay, which in skeletons, buried treasures,

and trees that bloomed with diamonds mingled

in confusion. All of them born of an imagination

wholly Oriental. Sometimes she told us that

men lived on the moon, which we could

perceive on it, were nothing else than the

woman who was forever weaving.

Você também pode gostar

- Archivetempattack On Titan - PremiumDocumento9 páginasArchivetempattack On Titan - PremiumKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

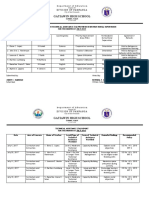

- Number of Vaccinated Students Grade Level and SectionDocumento1 páginaNumber of Vaccinated Students Grade Level and SectionKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Gatiawin High School: Division of PampangaDocumento3 páginasGatiawin High School: Division of PampangaKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

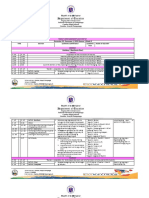

- Department of Education: Month: NOVEMBERDocumento2 páginasDepartment of Education: Month: NOVEMBERKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Review Related Literature?Documento17 páginasWhat Is Review Related Literature?Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Summary of Academic and CoDocumento1 páginaSummary of Academic and CoKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- 3RD Quarter Grade 8 PeDocumento11 páginas3RD Quarter Grade 8 PeKath Leen100% (3)

- THESIS (Depression)Documento13 páginasTHESIS (Depression)Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Group 9 EnglishDocumento35 páginasGroup 9 EnglishKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Research AddictionDocumento6 páginasResearch AddictionKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Ways On How Teenagers Cope Up With Thenegative Effects of Social MediaDocumento16 páginasWays On How Teenagers Cope Up With Thenegative Effects of Social MediaKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- JoshuaDocumento18 páginasJoshuaKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Group 6 10 - IsaiahDocumento10 páginasGroup 6 10 - IsaiahKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Baby Thesis For English 10Documento31 páginasBaby Thesis For English 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Music 8: Guided Learning Activity SheetsDocumento17 páginasMusic 8: Guided Learning Activity SheetsDonalyn Veruela Abon100% (1)

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento5 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento5 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Documento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Name: Jemilyn P. Dela Cruz Grade Level: Grade 10 Learning Area: ESP 10Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Writing The Research Conclusion: GroupDocumento13 páginasWriting The Research Conclusion: GroupKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Group 1 EnglishDocumento9 páginasGroup 1 EnglishKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Summative Test in Music 8Documento2 páginasDepartment of Education: Summative Test in Music 8Kimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Practicum Portfolio: LDM 2 Course FORDocumento20 páginasPracticum Portfolio: LDM 2 Course FORKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- Practicum Portfolio - Airish Joan GatusDocumento16 páginasPracticum Portfolio - Airish Joan GatusKimberly NgAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Research Final (Repaired)Documento29 páginasResearch Final (Repaired)vincent100% (1)

- Bahanajarcertaintykd1 131112085740 Phpapp02Documento5 páginasBahanajarcertaintykd1 131112085740 Phpapp02Buds PantunAinda não há avaliações

- Tigist ProposalDocumento41 páginasTigist ProposalTigist TameneAinda não há avaliações

- Reaction Paper: Katutubo (Memory of Dances)Documento2 páginasReaction Paper: Katutubo (Memory of Dances)Avatar KimAinda não há avaliações

- DeforestationDocumento14 páginasDeforestationHimanshu AmbeAinda não há avaliações

- Revised HOA Architectural Guidelines For CommentDocumento18 páginasRevised HOA Architectural Guidelines For CommentSan DeepAinda não há avaliações

- MA Catalogue2014 WEBDocumento44 páginasMA Catalogue2014 WEBCalujnaiAinda não há avaliações

- Durham Boat: Historic Use On The Delaware RiverDocumento2 páginasDurham Boat: Historic Use On The Delaware Riverrazeemship0% (1)

- DDEX32 ShacklesBloodDocumento34 páginasDDEX32 ShacklesBloodGdawg100% (1)

- 1 NREL ReviewerDocumento16 páginas1 NREL Reviewer'Joshua Crisostomo'Ainda não há avaliações

- AfforestationDocumento4 páginasAfforestationGeorgel MateasAinda não há avaliações

- NGP Assessment-Pidsdps1627Documento99 páginasNGP Assessment-Pidsdps1627Melitus NaciusAinda não há avaliações

- Acesorios DesbrozadoraDocumento49 páginasAcesorios DesbrozadoraAnonymous xvNiqFpVVpAinda não há avaliações

- Agriculture MeaningDocumento3 páginasAgriculture MeaningEmil BuanAinda não há avaliações

- Design - Construction Magazine (January To March 2020)Documento104 páginasDesign - Construction Magazine (January To March 2020)Renz ManaloAinda não há avaliações

- Paint Specifications and Product Data SheetsDocumento6 páginasPaint Specifications and Product Data SheetsAmir ShaikAinda não há avaliações

- Fruit Fly Control Products-1Documento1 páginaFruit Fly Control Products-1pamor2337Ainda não há avaliações

- Castlegar Slocan Valley Pennywise Apr 17Documento56 páginasCastlegar Slocan Valley Pennywise Apr 17Pennywise PublishingAinda não há avaliações

- Polillo Conservation DataDocumento20 páginasPolillo Conservation DatamgllacunaAinda não há avaliações

- Denevan Mito Prístino - MARCADO2Documento17 páginasDenevan Mito Prístino - MARCADO2Micaela RendeAinda não há avaliações

- Sampoerna Kayoe E-CATALOG PLYWOOD INGDocumento13 páginasSampoerna Kayoe E-CATALOG PLYWOOD INGReinardus RakkitasilaAinda não há avaliações

- Highway Bridge StructuresDocumento52 páginasHighway Bridge StructuresJaireAinda não há avaliações

- GK Questions On AgricultureDocumento8 páginasGK Questions On AgricultureAvinash GamitAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Forest Management (PEFC ST 1003:2010)Documento16 páginasSustainable Forest Management (PEFC ST 1003:2010)PEFC InternationalAinda não há avaliações

- Sloping Agricultural Land TechnologyDocumento12 páginasSloping Agricultural Land TechnologyBe ChahAinda não há avaliações

- Fr. Patangan RD., Sta. Filomena, Dipolog City 7100: DMC College Foundation Integrated SchoolDocumento3 páginasFr. Patangan RD., Sta. Filomena, Dipolog City 7100: DMC College Foundation Integrated SchoolPidol MawileAinda não há avaliações

- Eng-Oromo2Documento43 páginasEng-Oromo2aelemoo100% (2)

- Breeding Plan For SheepDocumento12 páginasBreeding Plan For SheepSuraj_Subedi100% (2)

- Sandalwood Essential OilDocumento5 páginasSandalwood Essential OilSpetsnaz DmitriAinda não há avaliações

- Study On Extraction of Bamboo Fibres From Raw Bamboo Fibres Bundles Using Different Retting TechniquesDocumento6 páginasStudy On Extraction of Bamboo Fibres From Raw Bamboo Fibres Bundles Using Different Retting TechniquesSEP-PublisherAinda não há avaliações