Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

GG

Enviado por

Ana Faith Ortega Ortiz-OlamitTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

GG

Enviado por

Ana Faith Ortega Ortiz-OlamitDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

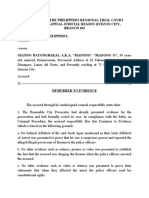

EXECUTION OF COMPROMISE AGREEMENT; DELAY BY ONE PARTY

JUSTIFIES EXECUTION

MANILA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY VS. ALA INDUSTRIES

CORPORATION

G.R. No. 147349. February 13, 2004

Facts: The contract for the structural repair and waterproofing of the IPT and ICT

building of the NAIA airport was awarded, after a public bidding, to respondent

ALA. Respondent made the necessary repair and waterproofing.

After submission of its progress billings to the petitioner, respondent received

partial payments. Progress billing remained unpaid despite repeated demands by

the respondent. Meanwhile petitioner unilaterally rescinded the contract on the

ground that respondent failed to complete the project within the agreed completion

date.

Respondent objected to the rescission made by the petitioner and reiterated its

claims. The trial court directed the parties to proceed to arbitration. Both parties

executed a compromise agreement and jointly filed in court a motion for judgment

based on the compromise agreement. The Court a quo rendered judgment

approving the compromise agreement.

For petitioners failure to pay within the period stipulated, respondent filed a

motion for execution to enforce its claim. Petitioner filed a comment and attributed

the delays to its being a government agency. The trial court denied the respondents

motion. Reversing the trial court, the CA ordered it to issue a writ of execution to

enforce respondents claim. The appellate court ratiocinated that a judgment

rendered in accordance with a compromise agreement was immediately executory,

and that a delay was not substantial compliance therewith.

Issues: 1) Whether or not decision based on compromise agreement is final and

executory.

2) Whether or not delay by one party on a compromise justifies execution.

Held: 1) A compromise once approved by final orders of the court has the force of

res judicata between the parties and should not be disturbed except for vices of

consent or forgery. Hence, a decision on a compromise agreement is final and

executory. Such agreement has the force of law and is conclusive between the

parties. It transcends its identity as a mere contract binding only upon the parties

thereto, as it becomes a judgment that is subject to execution in accordance with the

Rules. Judges therefore have the ministerial and mandatory duty to implement and

enforce it.

2. The failure to pay on the date stipulated was clearly a violation of the Agreement.

Thus, non-fulfillment of the terms of the compromise justified execution. It is the

height of absurdity for petitioner to attribute to a fortuitous event its delayed

payment. Petitioners explanation is clearly a gratuitous assertion that borders

callousness.

BPI vs. Casa Montessori Internationale, G. R.

No. 149454 & 149507, May 28, 2004

Post under case digests, Civil Law at Tuesday, January 31, 2012 Posted by Schizophrenic Mind

Facts: CASA Montessori International opened an account

with BPI, with CASAs President as one of its authorized

signatories. It discovered that 9 of its checks had been

encashed by a certain Sonny D. Santos whose name turned

out to be fictitious, and was used by a certain Yabut, CASAs

external auditor. He voluntarily admitted that he forged the

signature and encashed the checks.

RTC granted the Complaint for Collection with Damages

against BPI ordering to reinstate the amount in the account,

with interest. CA took account of CASAs contributory

negligence and apportioned the loss between CASA and

BPI, and ordred Yabut to reimburse both.

BPI contends that the monthly statements it issues to its

clients contain a notice worded as follows: If no error is

reported in 10 days, account will be correct and as such, it

should be considered a waiver.

Issue:Whether or not waiver or estoppel results from failure

to report the error in the bank statement

Held: Such notice cannot be considered a waiver, even if

CASA failed to report the error. Neither is it estopped from

questioning the mistake after the lapse of the ten-day

period.

This notice is a simple confirmation or "circularization" -- in

accounting parlance -- that requests client-depositors to

affirm the accuracy of items recorded by the banks. Its

purpose is to obtain from the depositors a direct

corroboration of the correctness of their account balances

with their respective banks.

Every right has subjects -- active and passive. While the

active subject is entitled to demand its enforcement, the

passive one is duty-bound to suffer such enforcement. On

the one hand, BPI could not have been an active subject,

because it could not have demanded from CASA a

response to its notice. CASA, on the other hand, could not

have been a passive subject, either, because it had no

obligation to respond. It could -- as it did -- choose not to

respond.

Estoppel precludes individuals from denying or asserting, by

their own deed or representation, anything contrary to that

established as the truth, in legal contemplation. Our rules on

evidence even make a juris et de jure presumption that

whenever one has, by ones own act or omission,

intentionally and deliberately led another to believe a

particular thing to be true and to act upon that belief, one

cannot -- in any litigation arising from such act or omission -be permitted to falsify that supposed truth.

In the instant case, CASA never made any deed or

representation that misled BPI. The formers omission, if

any, may only be deemed an innocent mistake oblivious to

the procedures and consequences of periodic audits. Since

its conduct was due to such ignorance founded upon an

innocent mistake, estoppel will not arise. A person who has

no knowledge of or consent to a transaction may not be

estopped by it. "Estoppel cannot be sustained by mere

argument or doubtful inference x x x." CASA is not barred

from questioning BPIs error even after the lapse of the

period given in the notice.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- School Climate QuestionnaireDocumento1 páginaSchool Climate QuestionnaireAnna-Maria BitereAinda não há avaliações

- CorpLaw 2014 Outline and CodalDocumento73 páginasCorpLaw 2014 Outline and CodalNori LolaAinda não há avaliações

- Approved Complaint SheetsDocumento4 páginasApproved Complaint SheetsAndrew SalamatAinda não há avaliações

- T8 Students DisciplineDocumento27 páginasT8 Students DisciplineDhiahVersatil100% (1)

- Complex Crime of Parricide with Unintentional AbortionDocumento2 páginasComplex Crime of Parricide with Unintentional AbortionAnonymous NqaBAyAinda não há avaliações

- Yolanda Mercado Vs AMA, DigestDocumento1 páginaYolanda Mercado Vs AMA, DigestAlan Gultia100% (1)

- PASSFAIL Checklist ComputerDocumento2 páginasPASSFAIL Checklist ComputerNiño Bryan AceroAinda não há avaliações

- Pestillos vs. GenerosoDocumento2 páginasPestillos vs. GenerosoKing BadongAinda não há avaliações

- WWWQDocumento2 páginasWWWQAna Faith Ortega Ortiz-OlamitAinda não há avaliações

- Mortem Examination On 11 December 1974. The Lower Court Allowed The Son of TheDocumento6 páginasMortem Examination On 11 December 1974. The Lower Court Allowed The Son of TheAna Faith Ortega Ortiz-OlamitAinda não há avaliações

- IIDocumento20 páginasIIAna Faith Ortega Ortiz-OlamitAinda não há avaliações

- Pryce vs PAGCOR Dispute Over Casino ClosureDocumento18 páginasPryce vs PAGCOR Dispute Over Casino ClosureAna Faith Ortega Ortiz-OlamitAinda não há avaliações

- LTA LOGISTICS Vs Enrique Varona (Varona Request of Production For Discovery)Documento4 páginasLTA LOGISTICS Vs Enrique Varona (Varona Request of Production For Discovery)Enrique VaronaAinda não há avaliações

- Succession Cases 7Documento64 páginasSuccession Cases 7Jo-Al GealonAinda não há avaliações

- Path of The Assassin v04 (Dark Horse)Documento298 páginasPath of The Assassin v04 (Dark Horse)Francesco CapelloAinda não há avaliações

- In Re - Genentech IncDocumento2 páginasIn Re - Genentech Incviva_33Ainda não há avaliações

- Dela Pena v. Dela Pena DigestDocumento2 páginasDela Pena v. Dela Pena DigestkathrynmaydevezaAinda não há avaliações

- Suntay vs. PeopleDocumento2 páginasSuntay vs. Peoplewiggie27Ainda não há avaliações

- Demurrer To EvidenceDocumento4 páginasDemurrer To EvidenceYanilyAnnVldzAinda não há avaliações

- Saudi Arabian Oil Company: Centrifugal Pump Data Sheet For Horizontal Pumps and Vertical In-Line PumpsDocumento6 páginasSaudi Arabian Oil Company: Centrifugal Pump Data Sheet For Horizontal Pumps and Vertical In-Line PumpsAnshu K MuhammedAinda não há avaliações

- HeadlessDocumento4 páginasHeadlessLupita1999Ainda não há avaliações

- Table Des Matières: de La LXXVII Année (2019/1-2) ArticlesDocumento2 páginasTable Des Matières: de La LXXVII Année (2019/1-2) ArticlesDumitru PrisacaruAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Procedure CasesDocumento10 páginasCivil Procedure CasesRam BeeAinda não há avaliações

- Eng Passive Voice - SoalDocumento8 páginasEng Passive Voice - SoalFiaFallen0% (1)

- Hindu LawDocumento8 páginasHindu LawSARIKAAinda não há avaliações

- ComplaintDocumento2 páginasComplaintKichelle May N. BallucanagAinda não há avaliações

- Read PDFDocumento6 páginasRead PDFRachel LopezAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal OwenDocumento21 páginasJurnal OwenJohan LeperteryAinda não há avaliações

- Gregory Alan Smith Wire Fraud Guilty PleaDocumento2 páginasGregory Alan Smith Wire Fraud Guilty PleaKHOUAinda não há avaliações

- The Sniper by Liam ODocumento2 páginasThe Sniper by Liam OWasif ZaAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Felix Pena-Jaquez, 3rd Cir. (2014)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Felix Pena-Jaquez, 3rd Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Relative ClausesDocumento1 páginaRelative ClausesValeria MirandaAinda não há avaliações

- Essay - The Downfall of The Iroquois ConfederacyDocumento2 páginasEssay - The Downfall of The Iroquois ConfederacyAsep Mundzir100% (1)

- Philippine National Oil Company vs. Court of AppealsDocumento121 páginasPhilippine National Oil Company vs. Court of AppealsMark NoelAinda não há avaliações