Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Flexible Arq 2

Enviado por

rojasrosasre67Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Flexible Arq 2

Enviado por

rojasrosasre67Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

theory

How might flexible housing be achieved? Determinate and

indeterminate approaches are examined using twentiethcentury examples

Flexible housing: the means to the end

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

Introduction1

The first paper (arq 9/2, pp. 157166) has already

made the arguments as to why flexible housing is a

relevant, even essential, part of future housing

provision on grounds of social, economic and

environmental sustainability. This paper examines

ways in which flexible housing may be achieved,

using examples from twentieth-century housing.

It is first necessary to define what we mean by

flexible housing. Our definition determines flexible

housing as housing that can adapt to the changing

needs of users. This definition is deliberately broad.

It includes the possibility of choosing different

housing layouts prior to occupation as well as the

ability to adjust ones housing over time. It also

includes the potential to incorporate new

technologies over time, to adjust to changing

demographics, or even to completely change the

use of the building from housing to something else.

So flexible housing in our definition is a wider

category than that of adaptable housing, which is

the term generally used to denote housing that can

adapt to users changing physical needs, in

particular as they grow older or lose full mobility.2

With such a broad definition, it is maybe not

surprising that there are multiple methods of

achieving flexibility. The approach in this paper is

not prescriptive and does not attempt to organise

these different approaches into an overall

methodology. Instead it explores flexibility through

the issue of determinate and indeterminate design,

or as we identify hard and soft systems. This differs

from the previous approaches of categorising

flexibility, most notably that derived out of the

open building movement. Kendall and Teichers

Residential Open Building is probably the most

comprehensive and rigorous analysis of flexible

housing of recent years.3 However, while the social

intents and economic rationale are admirable,

the method tends towards suggesting an all-ornothing approach that is eventually technically

determined. This is potentially off-putting to the

housing designer or provider. Our approach starts

with some basic principles and then suggests

alternative methods of achieving flexibility that

allow anything from wholesale change down to

quite discreet, but potentially extremely useful

alterations.

Built-in obsolescence

The basic principles of flexibility start with its

opposite namely that inflexibility should be

designed out. As noted in the first paper, the UK

building industry tends to build in obsolescence, but

this can be avoided in three manifestly simple, and

non-costly, ways. First, through the consideration of

the construction; most directly through the

reduction of loadbearing or solid internal partitions

but also through the avoidance of forms of roof

construction (i.e. trussed rafters) that close down the

possibility of future expansion. Second, through

technological considerations and in particular the

reduction of non-accessible or non-adaptable

services. Third, through consideration of the use of

space, i.e. through the elimination of tight-fit

functionalism and rooms that can be used or

accessed in only one way.

While these three relatively simple principles

would go some way to avoid inflexibility, one other

aspect also needs to be addressed. To move from

avoiding inflexibility to building-in flexibility it is

useful to look to see if we can find generic principles

in two building types that are often described as

inherently flexible, the English terraced house and

the speculative office.

The terraced house

In the course of our research by far the most

commonly mentioned example of flexibility was the

London terraced house, in particular the late

eighteenth-/early nineteenth-century examples

which are typically flat-fronted and three or four

stories, plus basement. Over the course of the years,

these have been added both horizontally (at the

back) and vertically (the ubiquitous loft extension),

knocked through, divided, joined up again and used

for countless other purposes.4 It is worth, therefore,

analysing the aspects of these houses that give them

their inherent flexibility. The first is the relatively

generous space provision in relation to

theory

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

287

288

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

theory

contemporary standards. This has allowed

subdivision both horizontally and vertically;

typically the front room might be divided to provide

a kitchen next to the living room, or a bathroom

might be inserted between the first floor front and

back rooms; vertically the generous height allows

false ceilings for services where necessary. Second,

their construction repeats a small number of simple

techniques, allowing the use of relatively unskilled

labour (the infamous and probably mythical firm of

Bodgit and Creepaway comes to mind). Finally, the

basic layout, and in particular the placing of the

staircase allows additions to be made at the rear of

the building in a flexible and infinitely variable

manner (the ubiquitous back extension).

While not all these aspects of the terraced house

can be transferred directly to the contemporary

context, they do begin to suggest some generic

principles for flexible housing. These are:

1 Space: There is a correlation between amount of

space and amount of flexibility. Some recent

schemes have exploited this correlation by

providing more space but at lower specification,

arguing that flexibility in the occupation of space

is of more importance than the niceties of having a

fitted kitchen or fully decorated rooms. One such

is the Nemausus scheme in Nmes, France (1985)

designed by Jean Nouvel. Here undivided space

with double-height areas was handed over in a

semi-finished state for the tenants to fit out,

though their ultimate choice was restricted by a

number of impositional rules that dictated things

like the colour of their curtains.5 This is also

essentially the approach of the loft developer,

where an excess of undefined space is handed over

to the tenant to use as they will. The corollary of

the space-flexibility correlation is that limited

space may be seen to limit flexibility, but at the

same time there are often demands to use that

space in multiple ways; in these cases you have to

work harder to achieve flexibility through other

design methods.

2 Construction: There is a relationship between

construction techniques and flexibility. The

specialist and multi-headed approach to housing

construction, particularly in the UK, limits future

flexibility in so much as one needs specialised and

multiple skills to make any adaptations. Against

this, following the example of the terraced house,

many of the most successful contemporary

flexible housing schemes rely on simple and

robust construction techniques, which allow

future intervention, or at least place the specialist

elements such as services in easily accessible and

separate zones so that only one set of specialists is

needed to make changes. This latter strategy is in

contrast to standard construction when just to

update, say, wiring one needs to get, in addition to

the electrician, a carpenter to lift floors, a plasterer

to patch the ceiling and a decorator to make good

in addition to the electrician.

3 Design for adaptation: Simple, but considered

design moves such as the placing of staircases,

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

Flexible housing: the means to the end

service cores or entrances allow future flexibility at

no extra cost. However, for this approach to be

successful the designer has to project future

scenarios and adaptations onto the plan to see

what can be accommodated. Exemplary of this

approach is the work of the architect Peter

Phippen in the UK, with the development of his

wide frontage house with a central service and

staircase core. This plan form allows free

disposition of rooms around the edges, as well the

possibility to make additions to the rear of the

property.

A few contemporary architects have specifically

followed these principles, most notably Caruso St.

Johns project for terraced housing in Berlin (2001)

which draws on the plan form of the traditional uk

terraced house, but provides still further flexibility

by making all the internal walls non-loadbearing.6

The scheme is at the same time simple and

sophisticated.

The speculative office

The second type of accommodation that is often

mentioned as inherently flexible is speculative

commercial offices. These are designed with no

specific tenant in mind and allow continual

adaptations to be made to the basic shell to suit the

occupants at any given time.7 Importantly, they also

allow upgrading and easy relocation of services.

Again, we can identify generic principles that can be

transferred to flexible housing;

4 Layers: The clear identification of layers of

construction from structure, skin, services,

internal partitions to finishes. This allows

increasing control (and so flexibility) as one goes

through the layers.8

5 Typical plan: The speculative office is the classic

shell and core structure. The external shell is

relatively inflexible; the core provides access and

services. In between the space is indeterminate,

with large spans and open plans allowing nonloadbearing partitions to be put in and removed at

will. The speculative office, almost by definition,

provides generic space, in contrast to the highly

specific and determined space that one finds in

most housing. It is what Rem Koolhaas denotes the

typical plan zero degree architecture,

architecture stripped of all traces of uniqueness or

specificity.9

6 Services: The disposition of services in the

speculative office is carefully considered to allow

future change and upgrading. Vertical services are

marshalled into easily accessible ducts.

Horizontally, raised floors and/or dropped ceilings

allow endless permutations in the eventual

disposition of service outlets.

Some of these principles from the speculative office

have already been exploited in schemes such as

Immeubles Lods in France (1972) which explicitly

used office building technology and planning

principles to give maximum flexibility in the

theory

housing (1970). The obverse is also becoming quite

common, with 1960s and 70s office buildings, which

no longer have the floorplates or storey height to

deal with contemporary office needs and servicing,

lending themselves to be converted into housing.

Using these six principles of inherent flexibility

from the terraced house and the speculative office

you can begin to enter the territory of designing

specifically for flexibility in housing. The next stage

of our research, and this paper, attempts to develop a

more comprehensive classification of methods by

which flexibility may be achieved in housing. Our

classification draws on some previous approaches,10

and while it attempts to cover most conditions of

flexibility, it does not intend to be prescriptive in

setting out a set of rigid rules for potential designers.

Our classification works in two directions. First,

through investigating flexibility at different scales of

housing (from the block, through the building and

unit, to the individual room), and second, by

indicating methods by which flexibility has been or

may be achieved. The rest of the paper concentrates

on the latter; we propose two broad categories, use

and technology. Use refers generally to the way that

the design affects the way that housing is occupied

over time, and generally refers to flexibility in plan.

Technology deals with issues of construction and

servicing, and the way that these affect the potential

for flexibility. We then subdivide each of these two

categories into soft and hard techniques.

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

Hard and soft

Soft refers to tactics which allow a certain

indeterminacy, whereas hard refers to elements

that more specifically determine the way that the

design may be used. In terms of use it may appear a

contradiction that flexibility can be achieved

through being either very indeterminate in plan

form or else very determinate, but historically both

approaches have developed in parallel throughout

the twentieth century. Soft use allows the user to

adapt the plan according to their needs, the designer

effectively working in the background.11 With hard

use, the designer works in the foreground,

determining how spaces can be used over time. As we

shall see, soft use generally demands more space,

even some redundancy, and is based on a relaxed

approach to both planning and technology, whereas

hard use is generally employed where space is at a

premium and a room has to be multifunctional.

Soft use

The notion of soft use is embedded in the vernacular

house. As Paul Oliver, the key historian of vernacular

architecture notes, with the growth of families,

whether nuclear or extended, the care of young

children and the infirm, and the death of the aged,

the demands on the dwelling to meet a changing

family size and structure are considerable.12 In

vernacular housing, the range of responses to these

issues is then oriented by culture and climate,

1 Britz Housing, Berlin

(1925) by Taut and

Wagner. Typical plan

from the

horseshoe block

Flexible housing: the means to the end

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

289

290

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

theory

2 Letn apartment

block, Prague (1935)

by Eugene

Rosenberg. Typical

plans

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

3 Hellmutstrasse,

Zurich (1991), by

ADP Architektur und

Planung: possible

arrangements

Flexible housing: the means to the end

ranging from the single space used for the whole

gamut of family rituals to the simple division of the

traditional cottage. Clearly, the intervention of the

expert designer removes such approaches from the

realm of the vernacular, but nonetheless the

principles of soft use remain. Some of the pioneering

examples of Modernist housing explicitly use the

notion of indeterminacy as a response to the

housing shortage crisis in the 1920s and 30s, arguing

that a flexible approach could cater for a wider range

of occupants. Typical of these is the Britz Project in

Berlin (192531) designed by Taut and Wagner. The

design provides three similarly sized rooms (denoted

on the plan simply as Zimmer room) off a central

hallway, with the services (bathroom and kitchen) in

a separate zone. The occupation of the rooms is

thereby left open to the interpretation by various

possible user groups [1].

A more refined version of this strategy can be

found in one of the classic projects of Czech

Modernism, the Letn project in Prague (1935) by

Eugene Rosenberg in which each floor typically

comprises two apartments of different size.13 Within

the individual apartments, rooms are of an equal

size and can be accessed separately from a central

lobby, while the services are contained in a separate

zone [2].

This indeterminacy approach is also beautifully

exploited in the Hellmutstrasse scheme in Zurich

(1991) by ADP Architektur und Planung, which is one

of the most sophisticated flexible housing schemes

of recent years. The project arose out of a community

led approach with all members of a housing

cooperative contributing to the design process. The

design is spilt into three distinct horizontal zones. At

the top is a line of similarly sized rooms divided by

loadbearing partitions, and with the possibility of

inserting non-loadbearing partitions to define

circulation. Below this there is a row of serviced

spaces that can be either bathrooms or kitchens.

Finally, at the lowest level, there is a zone containing

what is usually a kitchen and living space, but which

can also be used as a self-contained studio

apartment. All apartments are accessed from an

external staircase and shared balconies. The overall

arrangement allows multiple arrangements to be

achieved, from large groups of single people living

together right down to self-contained one-person

studio apartments. The zoning also allows future

changes to be made with ease, though in practice

this would require neighbouring apartments to

simultaneously agree to changes in terms of

expansion and contraction [3].

If one approach to soft use depends on the

designer providing a physically fixed, but socially

flexible, layout, a more common solution is to

provide raw space that can then be divided according

to the needs of the occupants. This is not as

straightforward as it may sound. Provision of open

space alone does not suffice, or at least it may be

inefficient in terms of space usage. The designer has

to carefully consider the best points for access

(generally in the centre of the plan), the position of

servicing (either in specific zones or else widely

theory

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

This approach to indeterminate open space was

facilitated by the new constructional systems

available to the early Modernist architects, which

allowed larger span structures and light infill

partitions. Some of the earliest examples can

therefore be found in classic Modernist housing

schemes such as the model housing at the

Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart (1927). In the block

designed by Mies van der Rohe, a simple framed

structure allows the residents to divide their

apartments up as they wish, though the final layout

is limited by the positioning of columns; the

provision of the servicing is also minimal by todays

standards [4].

A more developed approach can be found in

schemes such as that at Montereau-Surville in France

(1971) designed by Les Frres Arsne-Henry, or the

Jrnbrott Experimental Housing in Sweden (1953). In

a 10-storey building at Montereau, only the central

service core is fixed with the remainder left open as

in a speculative office. The scheme is designed to a

900mm module, allowing WCs and bathrooms (900,

distributed) and the most efficient module size (a

standard module allows repetition in structural

division and components but should not limit

options for subdivision). To ensure an efficient and

flexible use of space, designers will often use

hypothetical layouts to test their access, servicing

and module strategies.

4 Weissenhofsiedlung,

Stuttgart (1927) by

Mies van der Rohe.

Generic layout

(bottom), typical

plans (top)

Flexible housing: the means to the end

5 Montereau-Surville

(1971): Les Frres

Arsne-Henry:

empty plans

prior to internal

division

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

291

292

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

theory

6 Maison Loucheur

(19289) by Le

Corbusier: day plan

(left) and night

plan (right)

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

7 Kleinwohnung

project (1931) by

Carl Fieger: day

plan (left) and

night plan (right)

Flexible housing: the means to the end

theory

1800), bedrooms (1800, 2700 and 3600) and living

rooms (2700, 3600 and 4500) to be accommodated.

The architects designed 10 hypothetical layouts, but

in the end none of these was taken up; the

prospective tenants quickly learned to plan on a

squared grid, especially if this exercise was done in

the actual spaces. The modular system extended to

the treatment of the external facades, so that the

exterior appearance was dependent on the tenants

chosen internal layout and positioning of panels, a

rare example of architects passing over aesthetic

control to others [5].14

The Jrnbrott Experimental Housing is one of the

few flexible housing schemes to have been properly

evaluated after occupation.15 Again it works on the

principle of an open plan space with fixed

bathrooms and kitchens, and tenants being shown

alternative layouts. A survey carried out 10 years after

completion found that the majority of changes had

been made within the smaller units. This finding

supports a common theme from our research

interviews, namely that the provision of more space

in itself provides a certain degree of flexibility, while

smaller units are exactly the ones that require the

most flexibility to be built in.

Hard use

The notion of soft space lends itself in particular to a

participative approach to design, allowing a degree

of tenant control at both design stages and over the

life of the building. In contrast, hard use is use that is

largely determined by the architect. To this extent

hard use is consistent with the typical desire of the

architect to keep control, and it is therefore maybe

not surprising that hard use is associated with some

of the twentieth centurys iconic architects. Thus in

the Maison Loucheur (19289) designed by Le

Corbusier, a combination of folding furniture and

sliding walls allows different configurations for day

and night. Le Corbusier, in typically polemical style,

argues that the purchaser is paying for 46m2 of space

but through the cleverness of the design is actually

getting 71m2 of effective space [6].

This scheme identifies some of the common

features of hard use. First, the way it operates best

where space is at a premium. Second, the use of

moving or folding components. Third, the highly

specific nature of the configurations produced.

Classic examples of hard use such as Lawn Road

apartments (1934) by Wells Coates, the seminal

Schrder Huis (1924) by Rietveld, and

Kleinwohnung project (1931) by Carl Fieger,

all use these strategies [7].

There are comparatively few hard use flexible

housing schemes in relation to the continuing

interest in soft use approaches; they are generally

confined to demonstration or one-off projects, and

usually accompanied by a rhetorical stance which

may be at odds with the real needs of the users, for

whom the discipline of moving walls and folding

beds on a daily basis is likely to be over-onerous. The

fate of Lawn Road is instructive here. Originally the

scheme was occupied by a group of young

intellectuals, including Marcel Breuer, Lszl

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

Moholy-Nagy, and Agatha Christie, who were

sympathetic with the ideology of the project. As they

moved on, the apartments became increasingly

difficult to rent out, and eventually the empty

scheme fell into disrepair. Following its recent

renovation, Lawn Road now houses a mixture of

government keyworkers in shared ownership

tenure (nurses, teachers and so on who would

otherwise not be able to afford London house prices)

and young professionals, apparently attracted by the

lifestyle choice that the apartments offered, though

not put off by the very high cost per square metre of

the leasehold apartments.16 The minimal space

standards and discipline associated with hard use

may thus have a future relevance for two groups of

people, one of which has no other choice but accept

small, the other which sees small as a beautiful

lifestyle accessory.

Technology

If one method of achieving flexibility in housing is

through a consideration of use through design in

plan, another is through the deployment of

technology.17 Clearly these two approaches are not

mutually exclusive. We have seen how the

development of long span structures allowed the

elimination of loadbearing partitions, which in turn

allows soft use. However, in other schemes it is the

chosen technology rather than the specifics of the

plan that is seen as the primary means of achieving

flexibility. Technology here encompasses

construction techniques, structural solutions, and

servicing strategies, or a combination of these

approaches. Again we have divided these approaches

into hard and soft.

Hard technology

By hard technologies we mean those technologies

that are developed specifically to achieve flexibility,

and which are the determining feature of the

scheme. Of all these, the approach that has been most

systematically developed is that of the open building

movement. This grew out of John Habrakens research

and his book Supports: an alternative to mass housing.

The book is based around a critique of mass housing,

arguing that mass housing reduces the dwelling to a

consumer article and the dweller to consumer.18

Habraken argues for an alternative in which the user

is given control over the processes of dwelling. The

bold move in the book is then to harness this social

programme to a technical solution. The basic

principles are straightforward, namely that housing

should be considered as a structure of supports and

infills. The supports provide the basic infrastructure

and are designed as a long-life permanent base. The

infills are shorter life, user determined and

adaptable. The support and infill approach also

implies different levels of involvement on the part of

the user and professional, with professionals

relinquishing complete control, particularly at the

level of the infills. So far so good. Reading the sections

on supports forty years after they were first written,

one is struck by their polemical and open-ended

nature; they should be seen as a challenge to

Flexible housing: the means to the end

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

293

294

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

theory

flexible housing, but can be traced in the course of

twentieth-century attitudes to technology.23

8 Genter Strasse,

Munich (1972) by

Otto Steidle with

Doris and Ralph

Thut; frame and infill

9 Diagoon Houses,

Delft (1971) by

Herman

Hertzberger.

normative ways of thinking, but have instead been

taken on as a more determinist orthodoxy under the

flag of open building.

In the few examples of open building that have

actually been constructed, the emphasis has shifted

to the technical and constructional aspects and away

from the more socially grounded implications of

flexible housing. So it is not surprising that the

initial interest in open building in the early 1970s

waned because of the dearth of available technical

solutions such as suitable infill systems.19 One of the

few UK projects constructed at the time (the so-called

PSSHAK scheme at Adelaide Road, 1979) has hardly

been changed over the intervening years despite the

explicit flexible intent of the constructional

technique; the main reason is apparently that the

instructions as to how the infill kit could be adapted

were not passed on to subsequent tenants.20

The main outlet for open building has been in

Japan where the Ministry of Construction has

funded a number of experimental projects, most of

which have been driven by a technically determined

agenda.21 This is not to deny that the essential

principles of open building do address the needs of

flexible housing. However, there is a danger in these

and other open building projects of getting obsessed

by the techniques, and in this the technology

becomes an end in itself rather than a background

means to an end. This determinist aspect of hard

technology22 is not, of course, limited to the field of

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

Flexible housing: the means to the end

Soft technology

Architects are notoriously susceptible to siren calls of

technology as a means (but quickly becoming the

ends) of denoting presumed progress. The

foregrounding of hard technology allows these

delusions to be perpetuated. This suggests that in

flexible housing, as in other architecture, one

should move from the determinism of hard

technology to the enabling background of soft

technology. Soft technology is the stuff that enables

flexible housing to unfold in a manner not

completely controlled by the foreground of

construction techniques. In flexible housing this

approach can be seen in a number of schemes, many

of which exploit the layering principles of open

building, but in a more relaxed and less determinist

manner. So in the Genter Strasse scheme in Munich

(1972) designed by Otto Steidle with Doris and Ralph

Thut, a prefabricated frame can be filled according to

users needs and wants.24 Over the last 30 years,

volume, interiors, and uses have changed

considerably [8].

This scheme, and others like it, exploits soft

technology in the form of a structural system that

allows changes to be made at a future date. This

system may be in the form of an expressed frame, as

in the Genter Strasse scheme, or else simply a grid

structure that does away with the need for

loadbearing internal partitions, as in the

Brandhfchen scheme, Frankfurt (1995) designed by

Rdiger Kramm in which the structures only

loadbearing elements are beams and columns; none

of the internal walls is loadbearing, meaning that

even party walls can be removed to combine two

smaller units into one large unit. Small service cores

are located on each grid line (at the north facade),

allowing for a range of connection possibilities.

The provision of services, as in the Brandhfchen

scheme, is another aspect to be considered in the soft

technology approach. This can be achieved in three

ways. First, through the strategic placing of service

cores to allow kitchens and bathrooms to be placed

within specific zones but not to be permanently

fixed. Second, through the ability to access services

so that they can be updated at a later date. Third,

through the distribution of services across the

floorplate so that they can be accessed in any plan

arrangement. The way that most housing is serviced,

and in particular the wiring, remains an obstacle to

flexible housing. The incorporation of electrical

outlets into internal partitions is often necessary to

meet standards of provision or disability

requirements, but this also limits future change. The

distribution of services through raised floors

following office design principles gets over the first

but not the second of these problems; it is also

potentially more expensive. An alternative solution

to the servicing problem is the living wall concept

developed by PCKO Architects, in which services are

concentrated along a linear service wall, which is

easily accessed from the outside (to allow service

theory

providers to make changes with minimal disruption)

as well as internally (when internal layouts are

changed).

Conclusion

It will be seen from the above that our sympathies lie

with a soft approach to the design of flexible

housing. As noted, soft use and soft technology are by

no means mutually exclusive, and in the best

examples the social and technical aspects of the

project support each other, as in the Diagoon

Houses, Delft (1971) by Herman Hertzberger. The

principle behind the houses is based on the idea of

the incomplete building; meaning that a basic

frame leaves space for the personalised

interpretation of the user, i.e. number of rooms,

positioning, functional uses. The occupants

themselves will be able to decide how to divide the

space and live in it, where they will sleep and where

they will eat. If the composition of the family

changes, the house can be adjusted, and to a certain

extent enlarged. The structural skeleton is a halfproduct which everyone can complete according to

his own needs. The interiors show a fine balance

Notes

1. This paper is based on a research

project, The Past, Present and

Future of Flexible Housing,

funded by the Arts and

Humanities Research Council.

2. Caitriona Carroll, Julie Cowans

and David Darton, Meeting Part M

and Designing Lifetime Homes (York:

Joseph Rowntree Foundations,

1999).

Julie Brewerton and David Darton,

Designing Lifetime Homes (York:

Joseph Rowntree Foundations,

1997).

Christian Woetmann Nielsen and

Ivor Ambrose, Lifetime Adaptable

Housing in Europe, in Technology

and Disability 10, pt. 1 (1999), 1120.

3. Stephen Kendall and Jonathan

Teicher, Residential Open Building

(London and New York: E & FN

Spon, 2000).

4. Stefan Muthesius, The English

Terraced House (New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1982).

Michael Thompson, Rubbish Theory:

The Creation and Destruction of Value

(Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1979).

5. Lionel Duroy, Le Quartier

Nemausus, in Architecture

daujourdhui 252 (1987) 2-10.

Jacques Lucan, Nemausus 1,

Wohnberbauung mit Lofts,

Nmes, 1985, in werk, bauen +

wohnen 77/44 pt. 3 (1990), 5658.

6. Caruso St. John, Terraced House,

in a+t 13 (1999), 4447.

7. Bea Sennewald, Flexibility by

Design, in Architecture (AIA) 76, pt. 4

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

between order and chaos, the architecture accepting

but not getting overwhelmed by the vicissitudes and

changes of everyday life [9].

While most of the examples given have been at the

scale of the individual apartment, it is important to

note that our approach to flexible housing can and

should be applied at all scales. At the scale of the

whole building, soft use and/or technology will allow

both a variety of sizes in housing provision, as well as

the potential for mixed use. At the scale of the room,

flexibility can be considered through both use and

technology, the former in the consideration of how a

single room may be used for a variety of purposes,

the latter through the incorporation of flexible

components. At whatever scale, it is clear that

flexible housing can be achieved through a careful

consideration of use and technology and without

significant, if any, additional cost; it does not rely on

an overt display of formal or technological

gymnastics. In this, the soft approach to flexible

housing assumes a background role which, while

not necessarily according to the tendencies of

progressive display that architecture often adopts,

weaves itself into the heart of social empowerment.

(1987) 8994 (p. 90).

8. John Habraken, Supports: an

alternative to mass housing (London:

Architectural Press, 1972).

9. Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, S, M,

L, XL (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers,

1995), p. 325.

10. Hugo Priemus, Flexible housing:

fundamentals and background,

in Open House International 18, pt. 4

(1993), 1926.

Alexander Henz and Hannes Henz,

Anpassbare Wohnungen (Zrich: ETH

Wohnforum, 1997).

Stephen Kendall and Jonathan

Teicher, Residential Open Building

(London and New York: E & FN

Spon, 2000).

11. The term soft is drawn from

Jonathan Rabans seminal book on

urban culture, Soft City: the city

goes soft; it awaits the imprint of

an identity. For better or worse, it

invites you to remake it, to

consolidate it into a shape you can

live in.

Jonathan Raban, Soft City (London:

Hamilton, 1974), p. 11.

12. Paul Oliver, Dwellings: The Vernacular

House Worldwide (London: Phaidon,

2003), pp. 1667.

13. Rostislav Svcha, The Architecture of

New Prague 18951945 (Cambridge

MA: MIT Press, 1995), pp. 524.

14. Harald Deilmann, Jrg C.

Kirschenmann and Herbert

Pfeiffer, Wohnungsbau. The Dwelling.

Lhabitat. (Stuttgart: Karl Krmer

Verlag, 1973), pp. 378.

15. Statens institut for

byggnadsforskning, Flexible Flats:

an investigation in an experimental

block of flats in Jrnbrott, Gothenburg

(Stockholm: Statens institut for

byggnadsforskning, 1966).

16. Richard Carr, Lawn Road Flats,

(2004), from http://www.studiointernational.co.uk/architecture/

lawn_road_flats_7_6_04.htm

[accessed May 2005]

17. Alice Friedman makes it clear that

the divisible open plan design was

conceived in close collaboration

with the client for the house,

Truus Schrder, and so not the

whim of the architect as

controller.

Alice Friedman, Women and the

Making of the Modern House (New

York: Abrams, 1998), p. 71.

18. Habraken, p. 11.

19. Andrew Rabeneck, David Sheppard

and Peter Town, Housing

flexibility? Architectural Design 43,

pt. 11 (1973), 698727 (p. 701).

20. Rebecca Pike and Christopher

Powell, Housing Flexibility

Revisited in MADE 1 (2004), 6471

(p. 66).

21. Seiji Sawada and John Habraken,

Experimental Apartment

Building, Osaka, Japan, in Domus

819 (1999), 1825 (p. 21).

S. Kendall and J. Teicher, Residential

Open Building (London and New

York: E & FN Spon, 2000), pp. 245.

22. Open building is by no means

the only example of hard

technology in the flexible

housing sphere. Others include

the Danish Flexibo system and the

Optima housing system designed

Flexible housing: the means to the end

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

295

296

arq . vol 9 . nos 3/4 . 2005

theory

by Cartwright Pickard for the UK

market. See respectively:

Fllestegnestuen Flexibo,

Amager: Arkitekter:

Fllestegnestuen, with Viggo

Mller-Jensen, Tyge Arnfred and

Jrn Ole Srensen, in Arkitektur

DK 23, pt. 6 (1979), 2329 and D.

Littlefield, DIY for Architects, in

Building Design 1643 (2004) 201.

23. It should be noted that a few

schemes also consider the section

as means of allowing flexible use

over time. For example, the

unbuilt Projekt Wohnhaus (1984)

by Anton Schweighofer is based

on an unfinished double-height

space which the occupants would

grow into through the addition

of floors and walls. Anton

Schweighofer, A central space

as a kitchen studio: changeable

flats: projects and buildings;

Architects: Anton Schweighofer,

in werk, bauen + wohnen 71/38, pt. 3

Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider

(1984), 28-35.

24. Otto Steidle, Anpassbarer

Wohnungsbau, Baumeister 74, pt.

12 (1977), 11636.

Illustration credits

arq gratefully acknowledges:

Authors, 12, 47

ADP Architektur und Planung,

Zrich, 3

Steidle Architekten, Munich, 8

Herman Hertzberger, 9

Biographies

Jeremy Till is an architect and

Professor and Director of Architecture

at the University of Sheffield where he

has established an international

reputation in educational theory and

practice. His widely published written

work includes Architecture and

Participation and the forthcoming

Architecture and Contingency. He is a

Director in Sarah Wigglesworth

Architects, Chair of RIBA Awards Group

Flexible housing: the means to the end

and will represent Britain at the 2006

Venice Architecture Biennale.

Tatjana Schneider studied

architecture in Kaiserslautern,

Germany and Glasgow, Scotland. She

practised in Munich and Glasgow, and

researched a PhD at Strathclyde

University. Now a Research Associate

at Sheffield University, she is cowriting with Professor Jeremy Till a

book on Flexible Housing for

publication by Architectural Press.

Authors address

Professor Jeremy Till

Dr Tatjana Schneider

School of Architecture

University of Sheffield

Western Bank

Sheffield

s10 2tn

uk

j.till@sheffield.ac.uk

t.schneider@sheffield.ac.uk

Você também pode gostar

- Flagg's Small Houses: Their Economic Design and Construction, 1922No EverandFlagg's Small Houses: Their Economic Design and Construction, 1922Ainda não há avaliações

- Theory: Flexible Housing: The Means To The EndDocumento10 páginasTheory: Flexible Housing: The Means To The Ende_o_fAinda não há avaliações

- New Life for Old Houses: A Guide to Restoration and RepairNo EverandNew Life for Old Houses: A Guide to Restoration and RepairNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (2)

- Flexible Housing: The Means To The EndDocumento11 páginasFlexible Housing: The Means To The EndtvojmarioAinda não há avaliações

- Shipping Container Homes: A Guide on How to Build and Move into Shipping Container Homes with Examples of Plans and DesignsNo EverandShipping Container Homes: A Guide on How to Build and Move into Shipping Container Homes with Examples of Plans and DesignsAinda não há avaliações

- Flexible Housing The Means To The EndDocumento10 páginasFlexible Housing The Means To The EndhollysymbolAinda não há avaliações

- Till Schneider 2005 As Published PDFDocumento11 páginasTill Schneider 2005 As Published PDFRoxana ManoleAinda não há avaliações

- Arq - Flexible Housing The Means To The EndDocumento11 páginasArq - Flexible Housing The Means To The EndSABUESO FINANCIEROAinda não há avaliações

- Arq Flexible Housing The Means To The EndDocumento11 páginasArq Flexible Housing The Means To The EndjosefbolzAinda não há avaliações

- Jeremy Till - Flexible Housing (1999, Paper)Documento21 páginasJeremy Till - Flexible Housing (1999, Paper)Roger KriegerAinda não há avaliações

- The Opportunities of Flexible HousingDocumento19 páginasThe Opportunities of Flexible HousinghollysymbolAinda não há avaliações

- Theory: Flexible Housing: Opportunities and LimitsDocumento10 páginasTheory: Flexible Housing: Opportunities and Limitse_o_fAinda não há avaliações

- The Opportunities of Flexible HousingDocumento18 páginasThe Opportunities of Flexible HousingdrikitahAinda não há avaliações

- Flexible Housing: Opportunities and LimitsDocumento5 páginasFlexible Housing: Opportunities and LimitsdrikitahAinda não há avaliações

- Cib DC28229Documento7 páginasCib DC28229Nishigandha RaiAinda não há avaliações

- 96 101 ISrael NagoreDocumento6 páginas96 101 ISrael NagoreDavid Mesa CedilloAinda não há avaliações

- Des4 Research CondoDocumento27 páginasDes4 Research CondoShaina May FlorizaAinda não há avaliações

- Freedom of Space - A STUDYDocumento40 páginasFreedom of Space - A STUDYMidhun RaviAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 4: Design For FlexibilityDocumento25 páginasUnit 4: Design For FlexibilityDr. R.L SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Adaptable Housing or Adaptable People - BeisiDocumento24 páginasAdaptable Housing or Adaptable People - BeisiGustavo GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- The Case For Flexible HousingDocumento18 páginasThe Case For Flexible HousingVolodymyr BosyiAinda não há avaliações

- Flexible HousingDocumento244 páginasFlexible HousingAdrian Blazquez Molina100% (1)

- Multi Storey Building ReviewedDocumento30 páginasMulti Storey Building ReviewedAbdulyekini AhmaduAinda não há avaliações

- Ibs BimDocumento15 páginasIbs BimZULKEFLE ISMAILAinda não há avaliações

- The Case For Flexible HousingDocumento18 páginasThe Case For Flexible HousingMariaIliopoulouAinda não há avaliações

- Enhancing Air Movement by Passive Means in Hot Climate BuildingsDocumento9 páginasEnhancing Air Movement by Passive Means in Hot Climate BuildingsAmirtha SivaAinda não há avaliações

- Interview With Anne Lacaton Lacaton andDocumento16 páginasInterview With Anne Lacaton Lacaton andsaba azaAinda não há avaliações

- Flexible ArchitectureDocumento53 páginasFlexible ArchitectureAr Reshma100% (3)

- Assignment No. 1 Current Housing Condition in The PhilippinesDocumento10 páginasAssignment No. 1 Current Housing Condition in The Philippinesgeraldine marquezAinda não há avaliações

- 1617 TW Brandini-Memoire SP16 PDFDocumento47 páginas1617 TW Brandini-Memoire SP16 PDFNabi KataAinda não há avaliações

- Flexible Living Through Space Optimization PDFDocumento22 páginasFlexible Living Through Space Optimization PDFAesthetic ArchAinda não há avaliações

- Concrete Centre Basements For HousingDocumento24 páginasConcrete Centre Basements For HousingFree_Beating_Heart100% (1)

- Flexible HousingDocumento184 páginasFlexible HousingvineethAinda não há avaliações

- HI TECH (Histroy) Presented by Smit PatelDocumento10 páginasHI TECH (Histroy) Presented by Smit PatelSmit PatelAinda não há avaliações

- Flexibility and Adaptability of The Living SpaceDocumento8 páginasFlexibility and Adaptability of The Living SpaceJobernjay GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- The Development of A Strategy For The Implementation of Adaptability in Building StructuresDocumento5 páginasThe Development of A Strategy For The Implementation of Adaptability in Building StructuresJayita ChakrabortyAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation Report False CeilingDocumento42 páginasDissertation Report False CeilingSomya Singh67% (3)

- Learning Pack 1 - Building Adapt & Conserv PrinciplesDocumento26 páginasLearning Pack 1 - Building Adapt & Conserv PrinciplesantonyaldersonAinda não há avaliações

- Frame and Generic Space AbstractDocumento9 páginasFrame and Generic Space AbstractGustavo GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- The Polyvalent Dwelling: B.A.J.LeupenDocumento5 páginasThe Polyvalent Dwelling: B.A.J.LeupenpianoAinda não há avaliações

- Litreture Study On APARTMENTDocumento7 páginasLitreture Study On APARTMENTbarnali_dev100% (2)

- Book 1 - Adaptables 2006 - The NetherlandsDocumento385 páginasBook 1 - Adaptables 2006 - The NetherlandsLUIS ALBERTO MARROQUIN RIVERAAinda não há avaliações

- Paper Futurability - Pakhuis Meesteren RotterdamDocumento14 páginasPaper Futurability - Pakhuis Meesteren RotterdamSarah HaazenAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1.2 1Documento15 páginasChapter 1.2 1Adrian Yaneza TorteAinda não há avaliações

- National University: M.F. Jhocson, Sampaloc, ManilaDocumento42 páginasNational University: M.F. Jhocson, Sampaloc, ManilaSean Ferry Dela CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Design ToolsDocumento7 páginasDesign ToolsKevin Acosta100% (1)

- Containers ArchitectureDocumento23 páginasContainers Architecturearie.nugrahaAinda não há avaliações

- Canepa 2017 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 245 052006Documento11 páginasCanepa 2017 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 245 052006Mabe CalvoAinda não há avaliações

- Design 8: University of Nueva Caceres J.hernadez Avenue Naga City College of Engineering and ArchitectureDocumento10 páginasDesign 8: University of Nueva Caceres J.hernadez Avenue Naga City College of Engineering and ArchitectureJayson OlavarioAinda não há avaliações

- Full Text 01Documento64 páginasFull Text 01Donia NaseerAinda não há avaliações

- Flexible Architecture-1Documento10 páginasFlexible Architecture-1vrajeshAinda não há avaliações

- Active House Concept Versus Passive House:, IncludingDocumento9 páginasActive House Concept Versus Passive House:, IncludingDeux ArtsAinda não há avaliações

- Microliving: Several Reasons For Micro LivingDocumento5 páginasMicroliving: Several Reasons For Micro LivingRajapandianAinda não há avaliações

- P4 Reflection Paper - Judith Stegeman - 15-03-2018: Problem: Families vs. Amsterdam and Unsuitable Family DwellingsDocumento7 páginasP4 Reflection Paper - Judith Stegeman - 15-03-2018: Problem: Families vs. Amsterdam and Unsuitable Family DwellingsRoxana ManoleAinda não há avaliações

- Polyvalence, A Concept For The Sustainable Dwelling: Bernard LeupenDocumento9 páginasPolyvalence, A Concept For The Sustainable Dwelling: Bernard LeupenkautukAinda não há avaliações

- 5 PuntosDocumento3 páginas5 PuntosAna Mae ArozarenaAinda não há avaliações

- Le Corbusier/Pierre Jeanneret: Five Points Towards A New ArchitectureDocumento2 páginasLe Corbusier/Pierre Jeanneret: Five Points Towards A New ArchitectureMuvida AlhasniAinda não há avaliações

- Tropical Architecture: Basic Design PrinciplesDocumento27 páginasTropical Architecture: Basic Design PrinciplesChristian Villena100% (3)

- Research Paper 4580761 Mengran WangDocumento17 páginasResearch Paper 4580761 Mengran WangdhanAinda não há avaliações

- Planning of BuildingDocumento11 páginasPlanning of BuildingVasant DhawaleAinda não há avaliações

- Digital Proceedings Criticall III #Un-ThologyDocumento105 páginasDigital Proceedings Criticall III #Un-ThologyunomasarquitecturasAinda não há avaliações

- FABRICACIONES Moma Catalogue 199 300199462Documento133 páginasFABRICACIONES Moma Catalogue 199 300199462rojasrosasre67Ainda não há avaliações

- Barbara and Michael Leisgen at ARCO Madrid 2016 Beta Pictoris Gallery Stand 9D11Documento8 páginasBarbara and Michael Leisgen at ARCO Madrid 2016 Beta Pictoris Gallery Stand 9D11rojasrosasre67Ainda não há avaliações

- Barbara and Michael Leisgen at ARCO Madrid 2016 Beta Pictoris Gallery Stand 9D11Documento8 páginasBarbara and Michael Leisgen at ARCO Madrid 2016 Beta Pictoris Gallery Stand 9D11rojasrosasre67Ainda não há avaliações

- GFRC vs. Green Wall Systems: Which Works More Efficiently?Documento26 páginasGFRC vs. Green Wall Systems: Which Works More Efficiently?Elanur MayaAinda não há avaliações

- Beautiful HomesDocumento13 páginasBeautiful HomesAqua Lake100% (1)

- Structural DrawingsDocumento1 páginaStructural DrawingserniE抖音 AI Mobile Phone Based MovieAinda não há avaliações

- Sheet Title: Part Plan of Toilet: Working DrawingDocumento1 páginaSheet Title: Part Plan of Toilet: Working DrawingAditiAinda não há avaliações

- Update Daily Activity 28-2Documento19 páginasUpdate Daily Activity 28-2Bayu BiroeAinda não há avaliações

- Transmaterial 2 PDFDocumento18 páginasTransmaterial 2 PDFSulman KhalidAinda não há avaliações

- Contoh CV ArchitectDocumento6 páginasContoh CV ArchitectSena SyahmirazAinda não há avaliações

- Artu K List Price 2022: With Effective From 10 June 2022Documento16 páginasArtu K List Price 2022: With Effective From 10 June 2022Pramod PatilAinda não há avaliações

- Climatic Analysis of A Haveli in Shekhawati Region, RajasthanDocumento7 páginasClimatic Analysis of A Haveli in Shekhawati Region, Rajasthanchirag100% (1)

- Floor and Joist ReplacementDocumento8 páginasFloor and Joist ReplacementShristina ShresthaAinda não há avaliações

- Elemental Cost AnalysisDocumento4 páginasElemental Cost AnalysisadamAinda não há avaliações

- LECTURE 9 - DE STIJL and EXPRESSIONISM ARCHITECTUREDocumento22 páginasLECTURE 9 - DE STIJL and EXPRESSIONISM ARCHITECTUREIzzul FadliAinda não há avaliações

- Working of MivanDocumento5 páginasWorking of MivanAnuja JadhavAinda não há avaliações

- AISI Section 092600 - Metal Framing For Gypsum Board AssembliesDocumento6 páginasAISI Section 092600 - Metal Framing For Gypsum Board AssembliesĐường Nguyễn ThừaAinda não há avaliações

- B.INGGRIS KELAS 7 PERTEMUAN 17 (UH) - Muhar ResmiraDocumento4 páginasB.INGGRIS KELAS 7 PERTEMUAN 17 (UH) - Muhar ResmiraramaAinda não há avaliações

- RFI 0001 - Steel Specification Changes For Anchor RodsDocumento4 páginasRFI 0001 - Steel Specification Changes For Anchor Rodsjose Carlos Franco ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Heramb Marathe-Folded Structures ReportDocumento25 páginasHeramb Marathe-Folded Structures ReportHeramb MaratheAinda não há avaliações

- Metsec Steel Framing SystemDocumento46 páginasMetsec Steel Framing Systemleonil7Ainda não há avaliações

- Concrete Compressive Strength: As Per IS: 516Documento4 páginasConcrete Compressive Strength: As Per IS: 516Subas ChandAinda não há avaliações

- 8 Feb 180 SQ Bungalow Drawing RepairedDocumento29 páginas8 Feb 180 SQ Bungalow Drawing Repairedhazara naqsha naveesAinda não há avaliações

- EQc2 1 - Occupant-Comfort-Survey Results - SAMPLEDocumento5 páginasEQc2 1 - Occupant-Comfort-Survey Results - SAMPLEtran huu anh tuanAinda não há avaliações

- Tunnel FormworkDocumento14 páginasTunnel FormworkMohammed HajaraAinda não há avaliações

- Insulated FormworkDocumento2 páginasInsulated FormworkhimanshuAinda não há avaliações

- Pack 1B 1. Texts For Studying The Architectural VocabularyDocumento12 páginasPack 1B 1. Texts For Studying The Architectural VocabularyHustiuc RomeoAinda não há avaliações

- Literature and Data CollectionDocumento17 páginasLiterature and Data CollectionShaili83% (6)

- An Auditorium Case Study: Veer Savarkar Auditorium, Shivaji ParkDocumento15 páginasAn Auditorium Case Study: Veer Savarkar Auditorium, Shivaji Parkram shreevastavAinda não há avaliações

- NCR Log Sheet (CBPL)Documento6 páginasNCR Log Sheet (CBPL)lavekushAinda não há avaliações

- 3RD B Rev Chrystal East 1143 Renovation ProjectDocumento15 páginas3RD B Rev Chrystal East 1143 Renovation ProjectJaime Bolivar RoblesAinda não há avaliações

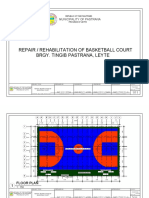

- Repair Rehabilitation of Basketball Court PlanDocumento11 páginasRepair Rehabilitation of Basketball Court PlanRezealf Ullasini AlferezAinda não há avaliações

- Frequently Asked QuestionsDocumento6 páginasFrequently Asked QuestionsChimmy GonzalezAinda não há avaliações

- House Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetNo EverandHouse Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetAinda não há avaliações

- Scary Smart: The Future of Artificial Intelligence and How You Can Save Our WorldNo EverandScary Smart: The Future of Artificial Intelligence and How You Can Save Our WorldNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (55)

- ChatGPT Side Hustles 2024 - Unlock the Digital Goldmine and Get AI Working for You Fast with More Than 85 Side Hustle Ideas to Boost Passive Income, Create New Cash Flow, and Get Ahead of the CurveNo EverandChatGPT Side Hustles 2024 - Unlock the Digital Goldmine and Get AI Working for You Fast with More Than 85 Side Hustle Ideas to Boost Passive Income, Create New Cash Flow, and Get Ahead of the CurveAinda não há avaliações

- Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human DecisionsNo EverandAlgorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human DecisionsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (722)

- Defensive Cyber Mastery: Expert Strategies for Unbeatable Personal and Business SecurityNo EverandDefensive Cyber Mastery: Expert Strategies for Unbeatable Personal and Business SecurityNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Generative AI: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewNo EverandGenerative AI: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (2)

- Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyNo EverandDigital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (51)

- ChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindNo EverandChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindAinda não há avaliações

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisNo EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (49)

- Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon ValleyNo EverandChaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon ValleyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (111)

- The Intel Trinity: How Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove Built the World's Most Important CompanyNo EverandThe Intel Trinity: How Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove Built the World's Most Important CompanyAinda não há avaliações

- Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About ItNo EverandCyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About ItNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (66)

- Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of PhilosophyNo EverandReality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of PhilosophyNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (24)

- The Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumNo EverandThe Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (12)

- ChatGPT Millionaire 2024 - Bot-Driven Side Hustles, Prompt Engineering Shortcut Secrets, and Automated Income Streams that Print Money While You Sleep. The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide for AI BusinessNo EverandChatGPT Millionaire 2024 - Bot-Driven Side Hustles, Prompt Engineering Shortcut Secrets, and Automated Income Streams that Print Money While You Sleep. The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide for AI BusinessAinda não há avaliações

- AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World OrderNo EverandAI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World OrderNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (398)

- A Place of My Own: The Architecture of DaydreamsNo EverandA Place of My Own: The Architecture of DaydreamsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (242)

- System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can RebootNo EverandSystem Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can RebootAinda não há avaliações

- The Simulated Multiverse: An MIT Computer Scientist Explores Parallel Universes, The Simulation Hypothesis, Quantum Computing and the Mandela EffectNo EverandThe Simulated Multiverse: An MIT Computer Scientist Explores Parallel Universes, The Simulation Hypothesis, Quantum Computing and the Mandela EffectNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (20)

- The Things We Make: The Unknown History of Invention from Cathedrals to Soda CansNo EverandThe Things We Make: The Unknown History of Invention from Cathedrals to Soda CansAinda não há avaliações

- Chip War: The Quest to Dominate the World's Most Critical TechnologyNo EverandChip War: The Quest to Dominate the World's Most Critical TechnologyNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (227)