Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Medicine Between Science and Religion Chapter1b

Enviado por

mamun310 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

31 visualizações2 páginasThe document discusses the complex interactions between Tibetan medicine and biomedicine over time. It describes three waves of encounters: (1) Early modern encounters in the late 19th/early 20th century as Tibetan practitioners incorporated some Western medical knowledge and technologies; (2) Intensive interactions from the 1950s onward as China introduced biomedical resources and reformed Tibetan medicine; (3) A third wave beginning in the early 21st century marked by globalization efforts like new factories/colleges and more rigorous scientific research on Tibetan medicines. The document emphasizes that Tibetan medicine has always been composite and integrative, in ongoing conversation with other medical traditions.

Descrição original:

A book on healing

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoThe document discusses the complex interactions between Tibetan medicine and biomedicine over time. It describes three waves of encounters: (1) Early modern encounters in the late 19th/early 20th century as Tibetan practitioners incorporated some Western medical knowledge and technologies; (2) Intensive interactions from the 1950s onward as China introduced biomedical resources and reformed Tibetan medicine; (3) A third wave beginning in the early 21st century marked by globalization efforts like new factories/colleges and more rigorous scientific research on Tibetan medicines. The document emphasizes that Tibetan medicine has always been composite and integrative, in ongoing conversation with other medical traditions.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

31 visualizações2 páginasMedicine Between Science and Religion Chapter1b

Enviado por

mamun31The document discusses the complex interactions between Tibetan medicine and biomedicine over time. It describes three waves of encounters: (1) Early modern encounters in the late 19th/early 20th century as Tibetan practitioners incorporated some Western medical knowledge and technologies; (2) Intensive interactions from the 1950s onward as China introduced biomedical resources and reformed Tibetan medicine; (3) A third wave beginning in the early 21st century marked by globalization efforts like new factories/colleges and more rigorous scientific research on Tibetan medicines. The document emphasizes that Tibetan medicine has always been composite and integrative, in ongoing conversation with other medical traditions.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 2

The Complexity of Encounters: Tibetan Medicine meets Biomedicine

The idea that Tibetan medicine, as a unitary or singular system, is

encountering biomedicine, as a separate system or tradition, is as

problematic as assuming a simple dichotomy of science/religion. The heuristic use of

biomedicine and Tibetan medicine in these pages is overwritten by ethnographic and

historical evidence which shows that there is a continuum of mutual interaction between

these varied traditions that makes it impossible to see them as entirely discrete systems of

medicine today. Indeed, the Tibetan medicine that we see today is nearly always

already in conversation with a variety of other traditions, and it is itself an

inherently integrative, composite set of diverse medical knowledge and

practices to begin with (Dummer 1988, Meyer 1981, Pordie 2008, Samuel

2001). Tibetan medicine continues to be an assemblage, a result of sociocultural

processes of accretion, borrowing and change. These chapters show

the unstable terrain of empiricism and epistemology in this process, in the

sense of there being ongoing translations back and forth from history and

in the present between medical traditions of many sorts.

Nevertheless, we need a way to account both for history and for the idea

that Tibetan medical practitioners have had to become self-conscious of

their differences as well as their commonalities with biomedicine.

Biomedicine demands this kind of self-reflexivity, as is classically true of

modernity (Langford 2002). Pordie writes that one finds a certain

neotraditionalism at work among those who want to claim the space for a

traditional Tibetan medicine, by which he means a revival of tradition as a

self-conscious claim to traditional versus modern Tibetan medicine (2008:

7). In this volume we often see that Tibetan medicine is not organized

around such a strategic essentialism, but rather around a dynamism of form

and technique, and even around theorizing about how to be efficacious.

We sense a more grounded and practical engagement with biomedicine

that subordinates debates about what constitutes authentic Tibetan

medicine for more pragmatic discussions about what cures work the best

to heal patients in specific contexts or with specific diseases.

Still, it is worth noting that there is a point to the heuristic distinction

which Pordie highlights, insofar as there have been and still are different

levels of historical engagement with biomedicine and with concepts of the

traditional within sowa rigpa practice; the degree of this engagement has

varied, depending on the type of practitioner, the location of practice and

the purpose of their work. Today, Tibetan medical ideas and techniques

are engaging with Western biomedicine at a number of levels and locations:

from the public health practices and pharmacies housed in rural Tibetan

clinics to the design and implementation of randomized controlled trials

(RCT) on Tibetan therapies to be conducted in China, India or Western

locales. These engagements are different still from those emerging at the

turn of the twentieth century, as McKay details. We might consider, in fact,

three successive waves of Tibetan encounters with biomedicine, while

remembering that biomedicine does not constitute an essential, uniform

set of practices or knowledge. Let us elaborate on each of these waves.

The First Wave

The turn of the twentieth century saw Tibetan practitioners travelling to

foreign lands and delivering medical services in these new locations in

conversation with, and sometimes absorbing features of, scientific medicine,

as it was understood at that time. These initial modern encounters constitute

the first wave. This was of course in the context of historical engagements

with other medical traditions (particularly Ayurvedic practitioners in

northern India and Chinese medical practitioners at the edges of the Tibetan

frontier). Similarly, early Western medical encounters occurred in Tibet by

way of the British as well as some missionaries, the latter being an area which

is less explored in existing scholarship (see McKay 2007). Although there

may not have been a deep intellectual engagement between biomedicine

and Tibetan medicine during the colonial British encounter (yet this may

have been more true in modernist Russia), we are shown that a transfer of

technology and knowledge was occurring. The first section of this volume

covers much of this ground.

The Second Wave

We demarcate the second wave of intensive interaction with scientific

medical models as the period from the 1950s onwards, when political

changes orchestrated by Chinese socialism brought with them a wide

variety of biomedical resources to Tibetan areas. Hospitals, clinics, the

barefoot doctor movement, and new medicines and technologies were all

introduced directly into urban and rural Tibetan communities over a fiftyyear

period. These reforms also included a direct revision of Tibetan

medicine through Chinese biomedicalization, the re-training of Tibetan

physicians as barefoot doctors, the attempt to eliminate important parts of

the theory of Tibetan medicine on the grounds that it contained religious

or superstitious elements, and the structuring of a hospital system that was

modelled on the biomedical resources emerging throughout China (Janes

1995, 1999). The initial experiences of Tibetan displacement and exile in

India, on the heels of Indias independence, and at a time when the country

itself was reframing medicine and public health in post-colonial terms, also

came to bear on how the Men-Tsee-Khang, reestablished in Dharamsala

in 1961, began to interact with biomedicine and Western science.

The Third Wave

A third wave of interaction with biomedicine began near the turn of the

twenty-first century. This period is marked by a simultaneous attempt to

revitalize and globalize Tibetan medicine through actions like the building

of new pharmaceutical factories and new colleges, and new kinds of

engagements with Western scientific models for research. In some ways

this last wave is marked by the trends that are more generally and

universally emerging in global health, particularly the growing emphasis on

pharmaceutical research and the market driven nature of Tibetan

medicines travels to areas beyond the Tibeto-Asian sphere. The third wave

is expansive, vast and certainly not uniform but has the appearance of being

totalizing in this expansiveness (from clinical trials on the efficacy of

meditation to the effectiveness of empowering medicines for a clinical

trial). The deep intellectual engagement between practitioners that was

missing from the early colonial and missionary encounters with

biomedicine is today a fundamental premise for the work that is

documented in the chapters in this volume

Você também pode gostar

- Culture, Health and Illness: An Introduction for Health ProfessionalsNo EverandCulture, Health and Illness: An Introduction for Health ProfessionalsAinda não há avaliações

- Musculoskeletal 20,000 Series CPT Questions With Answers-CpcDocumento16 páginasMusculoskeletal 20,000 Series CPT Questions With Answers-Cpcanchalnigam25100% (7)

- Jean-Pierre Wybauw - Fine Chocolates 2 - Great Ganache Experience-Lannoo (2008)Documento209 páginasJean-Pierre Wybauw - Fine Chocolates 2 - Great Ganache Experience-Lannoo (2008)Mi na100% (1)

- Cranial Nerve Test & Testing KitsDocumento1 páginaCranial Nerve Test & Testing Kitsmamun31100% (1)

- Tibetan Medicine and Subjectivity: An Exploration of Tibetan Corporeality and Chinese State PolicyDocumento83 páginasTibetan Medicine and Subjectivity: An Exploration of Tibetan Corporeality and Chinese State PolicyFloyd Miller100% (1)

- Nursing Care of A Family With An InfantDocumento26 páginasNursing Care of A Family With An InfantJc GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Venera - Khalikova 2021 Medical - Pluralism CeaDocumento21 páginasVenera - Khalikova 2021 Medical - Pluralism CeaSilvana Citlalli Torres CampoyAinda não há avaliações

- Venera - Khalikova 2021 Medical - Pluralism CeaDocumento21 páginasVenera - Khalikova 2021 Medical - Pluralism CeaBernadett SmidAinda não há avaliações

- C M: N C T Paul U. Unschuld: Hinese Edicine Ature Versus Hemistry and EchnologyDocumento8 páginasC M: N C T Paul U. Unschuld: Hinese Edicine Ature Versus Hemistry and EchnologymaggieAinda não há avaliações

- The Transmission and Practice of Chinese MedicineDocumento10 páginasThe Transmission and Practice of Chinese MedicineJumboAinda não há avaliações

- Schrempf 2007Documento454 páginasSchrempf 2007bodhi86Ainda não há avaliações

- Women and Gender in Tibetan MedicineDocumento263 páginasWomen and Gender in Tibetan MedicineLuz GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Herbs, Laboratories, and RevolDocumento15 páginasHerbs, Laboratories, and Revolhung tsung jenAinda não há avaliações

- History of Medicine 1Documento7 páginasHistory of Medicine 1pssinghal180Ainda não há avaliações

- Comparative Studies of Health Care SystemsDocumento14 páginasComparative Studies of Health Care SystemsszeonAinda não há avaliações

- AHS 548B (Unit2) Sakshi Garg MSC 4th SemDocumento7 páginasAHS 548B (Unit2) Sakshi Garg MSC 4th SemSakshi GargAinda não há avaliações

- Nepal: Asian EthnologyDocumento2 páginasNepal: Asian Ethnologyain_94Ainda não há avaliações

- Medicine, Anthropology, Community...Documento6 páginasMedicine, Anthropology, Community...Gretel PeltoAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Anthropology NoteDocumento37 páginasMedical Anthropology NoteKeyeron DugumaAinda não há avaliações

- The History of Chinese Medicine in The People S Republic of China and Its GlobalizationDocumento21 páginasThe History of Chinese Medicine in The People S Republic of China and Its GlobalizationJumboAinda não há avaliações

- 1 - 23 and 1 - 25 KleinmanDocumento19 páginas1 - 23 and 1 - 25 KleinmanLeilaVoscoboynicovaAinda não há avaliações

- Multicultural Approa of Tibetan WindDocumento7 páginasMulticultural Approa of Tibetan Windxin chenAinda não há avaliações

- Combining Stories: Reading Tibetan Medicine As A Western Narrative of HealingDocumento87 páginasCombining Stories: Reading Tibetan Medicine As A Western Narrative of HealingDevin Gonier100% (1)

- British Colonial Health Care Development and The Persistence of Ethnic Medicine in Peninsular Malaysia and SingaporeDocumento21 páginasBritish Colonial Health Care Development and The Persistence of Ethnic Medicine in Peninsular Malaysia and SingaporeAr AmirAinda não há avaliações

- Deepak Kumar-Indian Medicin AurvedaDocumento19 páginasDeepak Kumar-Indian Medicin Aurvedavivek555555Ainda não há avaliações

- JRV 054Documento5 páginasJRV 054Corvus CoraxAinda não há avaliações

- History of Health EducationDocumento6 páginasHistory of Health EducationCorrine Ivy100% (2)

- Tidwell 2019 Cancer and TM CorrelatesDocumento60 páginasTidwell 2019 Cancer and TM CorrelatesCezar SampaioAinda não há avaliações

- Intercultural Health in Ecuador An Asymmetrical and Incomplete ProjectDocumento18 páginasIntercultural Health in Ecuador An Asymmetrical and Incomplete ProjectRicardo JumboAinda não há avaliações

- Aztec Medicine, Health, and NutritionDocumento4 páginasAztec Medicine, Health, and NutritionNoelle SpitzAinda não há avaliações

- Medicine Between Science and Religion: Explorations on Tibetan GroundsNo EverandMedicine Between Science and Religion: Explorations on Tibetan GroundsAinda não há avaliações

- Lysander Nesamoni 198909 MPhilF Thesis PDFDocumento137 páginasLysander Nesamoni 198909 MPhilF Thesis PDFAnjani KumarAinda não há avaliações

- The Origin of Medical PracticeDocumento53 páginasThe Origin of Medical PracticejoeAinda não há avaliações

- PDFDocumento25 páginasPDFJudas FK TadeoAinda não há avaliações

- History of NaturopathyDocumento5 páginasHistory of Naturopathyglenn johnstonAinda não há avaliações

- Beyond Medicalisation - N. RoseDocumento3 páginasBeyond Medicalisation - N. RoseManuel Guerrero Antequera100% (1)

- AHS 547B (Unit4) Sakshi Garg MSC 4thDocumento5 páginasAHS 547B (Unit4) Sakshi Garg MSC 4thSakshi GargAinda não há avaliações

- Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture: An Exploration of the Borderland between Anthropology, Medicine, and PsychiatryNo EverandPatients and Healers in the Context of Culture: An Exploration of the Borderland between Anthropology, Medicine, and PsychiatryNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (4)

- How Tibetan Medicine in Exile Became A "Medical System"Documento16 páginasHow Tibetan Medicine in Exile Became A "Medical System"Tenzin TashiAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence 1 - Comparison Between Two Traditional Medical SystemsDocumento8 páginasEvidence 1 - Comparison Between Two Traditional Medical SystemsMafe WoAinda não há avaliações

- Christian TCMDocumento12 páginasChristian TCMapi-585321630100% (1)

- China's State Council Information Office On Dec. 6 Issued A White Paper On The Development of Traditional Chinese MedicineDocumento12 páginasChina's State Council Information Office On Dec. 6 Issued A White Paper On The Development of Traditional Chinese MedicineLeigh aliasAinda não há avaliações

- LeslieDocumento3 páginasLesliepriyadarshineepratikshya5Ainda não há avaliações

- Chinese Medicine Outside of ChinaDocumento8 páginasChinese Medicine Outside of ChinaRudi SitumorangAinda não há avaliações

- Foucault and The Medicalisation Critique: Deborah LuptonDocumento17 páginasFoucault and The Medicalisation Critique: Deborah LuptonLorena MariñoAinda não há avaliações

- How Tibetan Medicine in Exile Became A "Medical System"Documento15 páginasHow Tibetan Medicine in Exile Became A "Medical System"tahuti696Ainda não há avaliações

- Ahs - 547B (Unit-Iii & Iv) Cultural Disease and IllnessDocumento8 páginasAhs - 547B (Unit-Iii & Iv) Cultural Disease and IllnessSakshi GargAinda não há avaliações

- Untitled 1Documento69 páginasUntitled 1Nikhil BisuiAinda não há avaliações

- The Cultural Context of Health Illness and Medicine PDFDocumento287 páginasThe Cultural Context of Health Illness and Medicine PDFarollings100% (1)

- Alavi Islam Healing MasDocumento46 páginasAlavi Islam Healing MasCheriCheAinda não há avaliações

- Preguntas Historia de La Medicina 2013Documento47 páginasPreguntas Historia de La Medicina 2013Jaime MatarredonaAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding and Exploring Illness and Disease in South Africa: A Medical Anthropology ContextDocumento10 páginasUnderstanding and Exploring Illness and Disease in South Africa: A Medical Anthropology ContextEarmias GumanteAinda não há avaliações

- DR - Adi Setia Islamic Medicine ColloquiumDocumento11 páginasDR - Adi Setia Islamic Medicine ColloquiumIlham NurAinda não há avaliações

- Asian Medical SystemsDocumento12 páginasAsian Medical SystemsReggie ThorpeAinda não há avaliações

- Complementary and Alternative MedicineDocumento10 páginasComplementary and Alternative MedicineSuneel Kotte100% (1)

- Gender, Medicine, and Society in Colonial India: Women's Health Care in Nineteenth-And Early Twentieth-Century Bengal Sujata MukherjeeDocumento1 páginaGender, Medicine, and Society in Colonial India: Women's Health Care in Nineteenth-And Early Twentieth-Century Bengal Sujata MukherjeeSohail KhakwaniAinda não há avaliações

- 10 - Chapter 1 PDFDocumento34 páginas10 - Chapter 1 PDFRajeshAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S0140673621010035 MainDocumento2 páginas1 s2.0 S0140673621010035 MainSergio OrihuelaAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Anthropology A ReviewDocumento20 páginasMedical Anthropology A ReviewAsef AntonioAinda não há avaliações

- Medical AnthropologyDocumento5 páginasMedical Anthropologyankulin duwarahAinda não há avaliações

- Queer Theory and Biomedical Practice The BiomedicaDocumento15 páginasQueer Theory and Biomedical Practice The BiomedicaAbdullah Al MashoodAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Pharmacology Cheat Sheet: by ViaDocumento2 páginasIntroduction To Pharmacology Cheat Sheet: by Viamamun31100% (1)

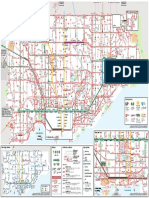

- TTC SystemMap 2021-11Documento1 páginaTTC SystemMap 2021-11Nava NavaAinda não há avaliações

- Chinese Ear PointsDocumento2 páginasChinese Ear Pointsmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Pharmacology 2 Cheat Sheet: by ViaDocumento5 páginasPharmacology 2 Cheat Sheet: by Viamamun31100% (2)

- TCM MicrosystemsDocumento2 páginasTCM Microsystemsmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 101 110Documento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 101 110mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 171 177Documento7 páginasAcupuncture For Body 171 177mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- PharmacologyDocumento11 páginasPharmacologymamun31100% (1)

- Acupuncture For Body 141 150Documento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 141 150mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 161 170Documento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 161 170mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Imaging 101 110 PDFDocumento10 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 101 110 PDFmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Key Muscle Locations and MovementsDocumento6 páginasKey Muscle Locations and Movementsmamun31100% (1)

- Acupuncture For Body 101 110 PDFDocumento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 101 110 PDFmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Imaging 111 125Documento15 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 111 125mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body, Mind and Spirit: Huo - FireDocumento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body, Mind and Spirit: Huo - Firemamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 91 100Documento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 91 100mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 11 20Documento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 11 20mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 31 40Documento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 31 40mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 41 50Documento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 41 50mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Imaging 101 110 PDFDocumento10 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 101 110 PDFmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Imaging 91 100 PDFDocumento10 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 91 100 PDFmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Imaging 91 100 PDFDocumento10 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 91 100 PDFmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 41 50 PDFDocumento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 41 50 PDFmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture For Body 1 10Documento10 páginasAcupuncture For Body 1 10mamun310% (1)

- Acupuncture Imaging 91 100Documento10 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 91 100mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Imaging 101 110Documento10 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 101 110mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Imaging 71 80Documento10 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 71 80mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Placebo Capacity, or Can Hinder It Severely!: Bodymind-Energetic Palpation 67Documento10 páginasPlacebo Capacity, or Can Hinder It Severely!: Bodymind-Energetic Palpation 67mamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Imaging 71 80 PDFDocumento10 páginasAcupuncture Imaging 71 80 PDFmamun31Ainda não há avaliações

- Exercise 3 ASC0304 - 2019-1Documento2 páginasExercise 3 ASC0304 - 2019-1Nuraina NabihahAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Odor From A Landfill Site On Surrounding Areas: A Case Study in Ho Chi Minh City, VietnamDocumento11 páginasImpact of Odor From A Landfill Site On Surrounding Areas: A Case Study in Ho Chi Minh City, VietnamNgọc HảiAinda não há avaliações

- Recipe Booklet PRINT VERSIONDocumento40 páginasRecipe Booklet PRINT VERSIONjtsunami815100% (1)

- Urie BronfenbrennerDocumento27 páginasUrie Bronfenbrennerapi-300862520100% (1)

- of Biology On Introductory BioinformaticsDocumento13 páginasof Biology On Introductory BioinformaticsUttkarsh SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Dowry SystemDocumento10 páginasDowry SystemBhoomejaa SKAinda não há avaliações

- OSCE Pediatric Dentistry Lecture-AnswersDocumento40 páginasOSCE Pediatric Dentistry Lecture-AnswersR MAinda não há avaliações

- Astm c126 Jtvo9242Documento5 páginasAstm c126 Jtvo9242Nayth Andres GalazAinda não há avaliações

- HRM Report CIA 3Documento5 páginasHRM Report CIA 3SUNIDHI PUNDHIR 20221029Ainda não há avaliações

- Baseline Capacity Assessment For OVC Grantee CSOsDocumento49 páginasBaseline Capacity Assessment For OVC Grantee CSOsShahid NadeemAinda não há avaliações

- Plumber PDFDocumento68 páginasPlumber PDFshehanAinda não há avaliações

- Fishing Broken Wire: WCP Slickline Europe Learning Centre SchlumbergerDocumento23 páginasFishing Broken Wire: WCP Slickline Europe Learning Centre SchlumbergerAli AliAinda não há avaliações

- TQM Assignment 3Documento8 páginasTQM Assignment 3ehte19797177Ainda não há avaliações

- Father of Different Fields of Science & Technology PDFDocumento3 páginasFather of Different Fields of Science & Technology PDFJacob PrasannaAinda não há avaliações

- National Step Tablet Vs Step Wedge Comparision FilmDocumento4 páginasNational Step Tablet Vs Step Wedge Comparision FilmManivannanMudhaliarAinda não há avaliações

- Elephantgrass Bookchapter PDFDocumento22 páginasElephantgrass Bookchapter PDFMuhammad rifayAinda não há avaliações

- Government of Canada Gouvernement Du CanadaDocumento17 páginasGovernment of Canada Gouvernement Du CanadaSaman BetkariAinda não há avaliações

- Publication PDFDocumento152 páginasPublication PDFAlicia Mary PicconeAinda não há avaliações

- Pipe TobaccoDocumento6 páginasPipe TobaccoVictorIoncuAinda não há avaliações

- FPSB 2 (1) 56-62oDocumento7 páginasFPSB 2 (1) 56-62ojaouadi adelAinda não há avaliações

- Registration of Hindu Marriage: A Project On Family Law-IDocumento22 páginasRegistration of Hindu Marriage: A Project On Family Law-Iamit dipankarAinda não há avaliações

- PAP and PAPE ReviewDocumento9 páginasPAP and PAPE ReviewYG1Ainda não há avaliações

- JAMB Biology Past Questions 1983 - 2004Documento55 páginasJAMB Biology Past Questions 1983 - 2004Keith MooreAinda não há avaliações

- Banco de Oro (Bdo) : Corporate ProfileDocumento1 páginaBanco de Oro (Bdo) : Corporate ProfileGwen CaldonaAinda não há avaliações

- Bagmati River Rejuvenation.1.0Documento27 páginasBagmati River Rejuvenation.1.0navonil.senAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4. Acid Base Problem Set: O O CH CH OH O O-H CH CH ODocumento2 páginasChapter 4. Acid Base Problem Set: O O CH CH OH O O-H CH CH Osnap7678650Ainda não há avaliações

- Commented (JPF1) : - The Latter Accused That Rizal HasDocumento3 páginasCommented (JPF1) : - The Latter Accused That Rizal HasLor100% (1)