Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Warranty Cases

Enviado por

Erica NolanDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Warranty Cases

Enviado por

Erica NolanDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

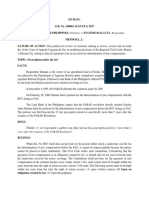

WARRANTIES CASES

PRUDENTIAL GUARANTEE v TRANS-ASIA SHIPPING

LINES

FACTS:

Plaintiff [TRANS-ASIA] is the owner of the vessel

M/V Asia Korea. In consideration of payment of

premiums, defendant [PRUDENTIAL] insured M/V

Asia Korea for loss/damage of the hull and

machinery arising from perils, inter alia, of fire and

explosion for the sum of P40 Million, beginning

[from] the period [of] July 1, 1993 up to July 1, 1994.

This is evidenced by Marine Policy No. MH93/1363

(Exhibits "A" to "A-11").

On October 25, 1993, while the policy was in force,

a fire broke out while [M/V Asia Korea was]

undergoing repairs at the port of Cebu.

NOTICE OF CLAIM. On October 26, 1993 plaintiff

[TRANS-ASIA] filed its notice of claim for damage

sustained by the vessel. This is evidenced by a

letter/formal claim of even date (Exhibit "B").

Plaintiff [TRANS-ASIA] reserved its right to

subsequently notify defendant [PRUDENTIAL] as to

the full amount of the claim upon final survey and

determination by average adjuster Richard Hogg

International (Phil.) of the damage sustained by

reason of fire.

Plaintiff [TRANS-ASIA] executed a document

denominated "Loan and Trust receipt. TRANS-ASIA

received P3M as a loan w/o interest from Prudential

Prudential denied Trans Asias claim due to alleged

breach of warranty.

COMPLAINT. TRANS-ASIA filed a complaint for sum

of money against Prudential w/ the RTC seeking the

amount of more then P8M upon the insurance

policy of P11M.

DEFENSE: breach of insurance policy conditions:

WARRANTY VESSEL CLASSED AND CLASS

MAINTAINED.

RTC: in favor of Prudential and return the P3M

loaned amt; determination of the parties liabilities

hinged on whether TRANS-ASIA violated and

breached the policy conditions on WARRANTED

VESSEL CLASSED AND CLASS MAINTAINED. It

interpreted the provision to mean that TRANS-ASIA

is required to maintain the vessel at a certain class

at all times pertinent during the life of the policy.

According to the court a quo, TRANS-ASIA failed to

prove compliance of the terms of the warranty, the

violation thereof entitled PRUDENTIAL, the insured

party, to rescind the contract.

CA: reversed; Pay amt of remaining P8M; it should

be Prudential who has the burden of proof to show

that TRANS-ASIA breached its warranty w/c burden

it failed to discharge. Prudential CANNOT rely on the

lack of cert. to the effect that TRANS-ASIA was

CLASSED AND CLASS MAINTAINED

I

ISSUE: W/N the court of appeals erred in holding

that there was no violation by trans-asia of a

material warranty, namely, warranty clause no. 5, of

the insurance policy

HELD:

PRUDENTIAL failed to establish that TRANS-ASIA

violated and breached the policy condition on

WARRANTED VESSEL CLASSED AND CLASS

MAINTAINED, as contained in the subject insurance

contract.

The warranty condition CLASSED AND CLASS

MAINTAINED was explained by PRUDENTIALs Senior

Manager of the Marine and Aviation Division, Lucio

Fernandez

A classification society is an organization which sets

certain standards for a vessel to maintain in order to

maintain their membership in the classification

society. So, if they failed to meet that standard, they

are considered not members of that class, and thus

breaching the warranty, that requires them to

maintain membership or to maintain their class on

that classification society. And it is not sufficient that

the member of this classification society at the time

of a loss, their membership must be continuous for

the whole length of the policy such that during the

effectivity of the policy, their classification is

suspended, and then thereafter, they get reinstated,

that again still a breach of the warranty that they

maintained their class (sic). Our maintaining team

membership in the classification society thereby

maintaining the standards of the vessel (sic).

We sustain the findings of the Court of Appeals that

PRUDENTIAL was not successful in discharging the

burden of evidence that TRANS-ASIA breached the

subject policy condition on CLASSED AND CLASS

MAINTAINED.

Foremost, PRUDENTIAL, through the Senior Manager

of its Marine and Aviation Division, Lucio Fernandez,

made a categorical admission that at the time of the

procurement of the insurance contract in July 1993,

TRANS-ASIAs vessel, "M/V Asia Korea" was properly

classed by Bureau Veritas,

NOT TANTAMOUNT TO BREACH. We are in accord

with the ruling of the Court of Appeals that the lack

of a certification in PRUDENTIALs records to the

effect that TRANS-ASIAs "M/V Asia Korea" was

CLASSED AND CLASS MAINTAINED at the time of the

occurrence of the fire cannot be tantamount to the

conclusion that TRANS-ASIA in fact breached the

warranty contained in the policy.

WARRANTY. We are not unmindful of the clear

language of Sec. 74 of the Insurance Code which

provides that, "the violation of a material warranty,

or other material provision of a policy on the part of

either party thereto, entitles the other to rescind." It

is generally accepted that "[a] warranty is a

statement or promise set forth in the policy, or by

reference incorporated therein, the untruth or nonfulfillment of which in any respect, and without

reference to whether the insurer was in fact

prejudiced by such untruth or non-fulfillment,

renders

the

policy

VOIDABLE

by

the

insurer."However, it is similarly indubitable that for

the breach of a warranty to avoid a policy, the same

must be duly shown by the party alleging the same.

We cannot sustain an allegation that is unfounded.

IN THE CASE AT BAR: Consequently, PRUDENTIAL,

not having shown that TRANS-ASIA breached the

warranty condition, CLASSED AND CLASS

MAINTAINED, it remains that TRANS-ASIA must be

allowed to recover its rightful claims on the policy.

ASSUMING ARGUENDO THAT THERE WAS A

VIOLATION OF WARRANTY: PRUDENTIAL made a

valid waiver of the same.

WAIVER. Third, after the loss, Prudential renewed

the insurance policy of Trans-Asia for two (2)

consecutive years, from noon of 01 July 1994 to

noon of 01 July 1995, and then again until noon of

01 July 1996. This renewal is deemed a waiver of any

breach of warranty.

RULING: PAY P8M REPRESENTING THE BAL. OF THE

LOSS SUFFERED BY TRANS-ASIA

YOUNG v MIDLAND TEXTILE INSURANCE

FACTS:

The plaintiff conducted a candy and fruit store on

the Escolta, in the city of Manila, and occupied a

building at 321 Calle Claveria, as a residence

and bodega.

The defendant, in consideration of the payment of a

premium of P60, entered into a contract of

insurance with the plaintiff (policy No. 509105) by

the terms of which the defendant company, upon

certain conditions, promised to pay to the plaintiff

the sum of P3,000, in case said residence

and bodega and contends should be destroyed by

fire.

WARRANTY. On the conditions of said contract of

insurance is found in "warranty B" and is as follows:

"Waranty B. It is hereby declared and agreed

that during the pendency of this policy no

hazardous goods stored or kept for sale, and no

hazardous trade or process be carried on, in the

building to which this insurance applies, or in any

building connected therewith

The

plaintiff

placed

in

said

residence

and bodega three boxes, 18 by 18 by 20 inches

measurement, which belonged to him and which

were filed with fireworks.

FIRE. On the 18th day of March, q913, said residence

and bodega and the contents thereof were partially

destroyed by fire.

ALLEGATION: Said fireworks had been given to the

plaintiff by the former owner of the Luneta Candy

Store; that the plaintiff intended to use the same in

the celebration of the Chinese new year; that the

authorities of the city of Manila had prohibited the

use of fireworks on said occasion, and that the

plaintiff then placed the same in said bodega, where

they remained from the 4th or 5th of February,

1913, until after the fire of the 18th of March, 1913.

Said fireworks were found in part of the bldg NOT

destroyed by fire

RTC: In favor of the plaintiff

ISSUE: Whether or not the placing of said fireworks

in the building insured, under the conditions above

enumerated, they being "hazardous goods," is a

violation of the terms of the contract of insurance

and especially of "warranty B"

HELD:

"Warranty B" provides that "no hazardous goods

be stored" in the building insured. It is admitted by

both parties that the fireworks are "hazardous

goods."

Both the plaintiff and defendant agree that if they

were "hazardous goods," and if they were "stored,"

then the act of the plaintiff was a violation of the

terms of the contract of insurance and the

defendant was justified in repudiating its liability

thereunder.

This leads us to a consideration of the meaning of

the accord "stored" as used in said "warranty B."

While the word "stored" has been variously defined

by authors, as well as by courts, we have found no

case exactly analogous to the present.

DEPENDS ON THE INTENTION OF THE PARTIES.

Whether a particular article is "stored" or not must,

in some degree, depend upon the intention of the

parties. The interpretation of the word "stored" is

quite difficult, in view of the many decisions upon

the various conditions presented. Nearly all of the

cases cited by the lower court are cases where the

article was being put to some reasonable and actual

use, which might easily have been permitted by the

terms of the policy, and within the intention of the

parties, and excepted from the operation of the

warranty, like the present.

STORE. The author of the Century Dictionary

defines the world "store" to be a deposit in a store

or warehouse for preservation or safe keeping; o

place in a warehouse or other place of deposit for

safe keeping. See also the definitions given by the

Standard Dictionary, to the same effect.

Said definitions, of course, do not include a deposit

in a store, in small quantities, for daily use. "Daily

use" precludes the idea of a deposit for preservation

or safe keeping, as well as a deposit for future

consumption, or safe keeping.

IN THE CASE AT BAR: In the present case no claim is

made that the "hazardous goods" were placed in

the bodega for present or daily use. It is admitted

that they were placed in the bodega "for future

use," or for future consumption, or for safe keeping.

The plaintiff makes no claim that he deposited

them there with any other idea than "for future

use" for future consumption. It seems clear to us

that the "hazardous goods" in question were

"stored" in the bodega, as that word is generally

defined. That being true, suppose the defendant had

made an examination of the premises, even in the

absence of a fire, and had found he "hazardous

goods" there, under the conditions above described,

would it not have been justified, then and there, in

declaring the policy null and of no effect by reason

of a violation of its terms on he par of the plaintiff?

The compliance of the insured with the terms of the

contract is a condition precedent to the right of

recovery. If the insured has violated or failed to

perform the conditions of the contract, and such a

violation or want of performance has not been

waived by the insurer, then the insured cannot

recover.

The violation of the terms of the contract, by virtue

of the provisions of the policy itself, terminated, at

the election of either party, he contractual relations.

The plaintiff paid a premium based upon the risk at

the time the policy was issued. Certainly it cannot be

denied that the placing of the firecrackers in the

building insured increased the risk. The plaintiff had

not paid a premium based upon the increased risk,

neither had the defendant issued a policy upon the

theory of a different risk. The plaintiff was enjoying,

if his contention may be allowed may be allowed,

the benefits of an insurance policy upon one risk,

whereas, as a matter of fact, it was issued upon an

entirely different risk. The defendant had neither

been paid nor had issues a policy to cover the

increased risk. An increase of risk which is

substantial and which is continued for a

considerable period of time, is a direct and certain

injury to the insurer, and changes the basis upon

which the contract of insurance rests.

RULING: DEFENDANT-INSURER RELIEVED FROM

LIAB.

AMERICAN HOME ASSURANCE

TANTUCO ENTERPRISES, INC.

COMPANY

FACTS:

Respondent Tantuco Enterprises, Inc. is engaged in

the coconut oil milling and refining industry. It

owns two oil mills. Both are located at factory

compound at Iyam, Lucena City.

The two oil mills were separately covered by fire

insurance policies issued by petitioner American

1

Home Assurance Co., Philippine Branch. The first

oil mill was insured for three million pesos

(P3,000,000.00) under Policy No. 306-7432324-3 for

2

the period March 1, 1991 to 1992. The new oil mill

was insured for six million pesos (P6,000,000.00)

under Policy No. 306-7432321-9 for the same

3

term. Official receipts indicating payment for the

full amount of the premium were issued by the

4

petitioner's agent.

FIRE. A fire that broke out in the early morning of

September 30,1991 gutted and consumed the new

oil mill.

NOTICE OF CLAIM. Respondent immediately

notified the petitioner of the incident. The latter

then sent its appraisers who inspected the burned

premises and the properties destroyed. Thereafter,

in a letter dated October 15, 1991, petitioner

rejected respondent's claim for the insurance

proceeds on the ground that no policy was issued

by it covering the burned oil mill. It stated that the

description of the insured establishment referred to

another building thus: "Our policy nos. 3067432321-9 (Ps 6M) and 306-7432324-4 (Ps 3M)

extend insurance coverage to your oil mill under

Building No. 5, whilst the affected oil mill was under

Building No. 14.

COMPLAINT. For specific perf. filed w/ RTC.

RTC: petitioner liable

ISSUE: W/N the CA erred in its interpretation of Fire

ext. Appliances Warranty

HELD:

The Petition is devoid of merit.

The primary reason advanced by the petitioner in

resisting the claim of the respondent is that the

burned oil mill is not covered by any insurance

policy.

However, it argues that this specific boundary

description clearly pertains, not to the burned oil

mill, but to the other mill. In other words, the oil mill

gutted by fire was not the one described by the

specific boundaries in the contested policy.

CONTENTIONS UNTENABLE.

In construing the words used descriptive of a

building insured, the greatest liberality is shown by

11

the courts in giving effect to the insurance. In view

of the custom of insurance agents to examine

buildings before writing policies upon them, and

since a mistake as to the identity and character of

the building is extremely unlikely, the courts are

inclined to consider that the policy of insurance

covers any building which the parties manifestly

intended to insure, however inaccurate the

description may be.

Notwithstanding, therefore, the misdescription in

the policy, it is beyond dispute, to our mind, that

what the parties manifestly intended to insure was

the new oil mill. This is obvious from the categorical

statement embodied in the policy, extending its

protection:

"On machineries and equipment with complete

accessories usual to a coconut oil mill including

stocks of copra, copra cake and copra mills whilst

contained in the new oil mill building, situate (sic) at

UNNO. ALONG NATIONAL HIGH WAY, BO. IYAM,

LUCENA CITY UNBLOCKED.

ALLEGED BREACH OF WARRANTY. The said warranty

provides:

"WARRANTED that during the currency of this Policy,

Fire Extinguishing Appliances as mentioned below

shall be maintained in efficient working order on the

premises to which insurance applies.

CONTENTION: Petitioner argues that the warranty

clearly obligates the insured to maintain all the

appliances specified therein. The breach occurred

when the respondent failed to install internal fire

hydrants inside the burned building as warranted.

This fact was admitted by the oil mill's expeller

operator, Gerardo Zarsuela.

NEED NOT PROVIDE FOR ALL. Again, the argument

lacks merit. We agree with the appellate court's

conclusion that the aforementioned warranty did

not require respondent to provide for all the fire

extinguishing appliances enumerated therein.

Additionally, we find that neither did it require that

the appliances are restricted to those mentioned in

the warranty. In other words, what the warranty

mandates is that respondent should maintain in

efficient working condition within the premises of

the insured property, fire fighting equipments such

as, but not limited to, those identified in the list,

which will serve as the oil mill's first line of defense

in case any part of it bursts into flame.

taken out with the Springfield Fire & Marine

Insurance Company. The warehouse was destroyed

by fire on January 11, 1928, while the policy issued

by the latter company was in force.

COMPLAINT. Predicated on this policy the plaintiff

instituted action in the Court of First Instance of

Manila against the defendant to recover a

proportional part of the loss coming to P8,170.59.

Four special defenses were interposed on behalf of

the insurance company, one being planted on a

violation of warranty F fixing the amount of

hazardous goods which might be stored in the

insured building

RTC: Against insurer

WARRANTY F

To be sure, respondent was able to comply with the

warranty. Within the vicinity of the new oil mill can

be found the following devices: numerous portable

21

fire

extinguishers,

two

fire

hoses, fire

22

23

hydrant, and an emergency fire engine. All of

these equipments were in efficient working order

when the fire occurred.

It ought to be remembered that not only are

warranties strictly construed against the insurer, but

they should, likewise, by themselves be reasonably

24

interpreted. That reasonableness is to be

ascertained in light of the factual conditions

prevailing in each case. Here, we find that there is

no more need for an internal hydrant considering

that inside the burned building were: (1) numerous

portable fire extinguishers, (2) an emergency fire

engine, and (3) a fire hose which has a connection

to one of the external hydrants.

RULING: PETITION DISMISSED.

ANG GIOK CHIP v SPRINGFILED FIRE AND MARITIME

INSURANCE CO.

FACTS:

Ang Giok Chip, doing business under the name and

style of Hua Bee Kong Si, was formerly the owner of

a warehouse situated at No. 643 Calle Reina

Regente, City of Manila. The contents of the

warehouse were insured with the three insurance

companies for the total sum of P60,000. One

insurance policy, in the amount of P10,000, was

It is hereby declared and agreed that during the

currency of this policy no hazardous goods be stored

in the Building to which this insurance applies or in

any building communicating therewith, provided,

always, however, that the Insured be permitted to

stored a small quantity of the hazardous goods

specified below, but not exceeding in all 3 per cent

of the total value of the whole of the goods or

merchandise contained in said warehouse, viz; . . . .

ISSUE: W/N there was violation of Warranty F?

HELD:

"Every express warranty, made at or before the

execution of a policy, must be contained in the

policy itself, or in another instrument signed by the

insured and referred to in the policy, as making a

part of it."

As the Philippine law was taken verbatim from the

law of California, in accordance with well settled

canons of statutory construction, the court should

follow in fundamental points, at least, the

construction placed by California courts on a

California law. Unfortunately the researches of

counsel reveal no authority coming from the courts

of California which is exactly on all fours with the

case before us. However, there are certain

consideration lying at the basis of California law and

certain indications in the California decisions which

point the way for the decision in this case

The law says that every express warranty must be

"contained in the policy itself." The word

"contained," according to the dictionaries, means

"included,"

inclosed,"

"embraced,"

"comprehended," etc. When, therefore, the courts

speak of a rider attached to the policy, and thus

"embodied" therein, or of a warranty "incorporated"

in the policy, it is believed that the phrase

"contained in the policy itself" must necessarily

include such rider and warranty.

This policy of insurance witnesseth, that E. M.

Bachrach, esq., Manila (hereinafter called the

insured), having paid to the undersigned, as

authorized agent of the British American Assurance

Company (hereinafter called the company), the

sum of two thousand pesos Philippine currency

(premium), for insuring against loss or damage by

fire, as hereinafter mentioned, the property

hereinafter described, in the sum of several sums

following, viz:

RIDER WARRANTY F. In other words, the rider,

warranty F, is contained in the policy itself, because

by the contract of insurance agreed to by the parties

it is made to form a part of the same, but is not

another instrument signed by the insured and

referred to in the policy as forming a part of it.

Ten thousand pesos Philippine currency, on goods,

belonging to a general furniture store, such as iron

and brass bedsteads, toilet tables, chairs, ice boxes,

bureaus, washstands, mirrors, and sea-grass

furniture (in accordance with warranty "D" of the

tariff attached hereto) the property of the assured,

in trust, on commission or for which he is

responsible, whilst stored in the ground floor and

first story of house and dwelling No. 16 Calle

Martinez, district 3, block 70, Manila, built, ground

floor of stone and or brick, first story of hard wood

and roofed with galvanized iron bounded in the

front by the said calle, on one side by Calle David

and on the other two sides by buildings of similar

construction and occupation.

We are given to understand, and there is no

indication to the contrary, that we have here a

standard insurance policy. We are further given to

understand, and there is no indication to the

contrary, that the issuance of the policy in this case

with its attached rider conforms to well established

practice in the Philippines and elsewhere. We are

further given to understand, and there is no

indication to the contrary, that there are no less

than sixty-nine insurance companies doing business

in the Philippine Islands with outstanding policies

more or less similar to the one involved in this case,

and that to nullify such policies would place an

unnecessary hindrance in the transaction of

insurance business in the Philippines. These are

matters of public policy. We cannot believe that it

was ever the legislative intention to insert in the

Philip.

VALID AND SUFFICIENT RIDER. We have studied this

case carefully and having done so have reached the

definite conclusion that warranty F, a rider attached

to the face of the insurance policy, and referred to in

contract of insurance, is valid and sufficient under

section 65 of the Insurance Act.

RULING: PETITION DISMISSED.

The Company agrees that the insured will be paid

NOT exceeding P10,000 upon a condition that the

insured shall have paid to the company. The policy

includes the Calalac automobile of petitioner;

permission was thereby granted for the use of the

gas for the above automobile while contained in the

reservoir of the car

FIRE. That the plaintiff, on the 18th of April, 1908,

and immediately preceding the outbreak of the

alleged fire, willfully placed a gasoline can containing

10 gallons of gasoline in the upper story of said

building in close proximity to a portion of said goods,

wares, and merchandise, which can was so placed by

the plaintiff as to permit the gasoline to run on the

floor of said second story, and after so placing said

gasoline, he, the plaintiff, placed in close proximity

to said escaping gasoline a lighted lamp containing

alcohol, thereby greatly increasing the risk of fire.

QUAJ CHEE GAN v LAW UNION ROCK

BACHRACH v BRITISH AMERICAN ASSURANCE

CORP.

COMPLAINT.Plaintiff filed a complaint claiming

recovery of sums due upon the insurance policy.

RTC: defendant liable to plaintiff

FACTS:

ISSUE: W/N the keeping of gasoline is in violation of

the policy

HELD:

It is claimed that either gasoline or alcohol was kept

in violation of the policy in the bodega containing

the insured property.

The property insured consisted mainly of household

furniture kept for the purpose of sale. The

preservation of the furniture in a salable condition

by retouching or otherwise was incidental to the

business. The evidence offered by the plaintiff is to

the effect that alcohol was used in preparing varnish

for the purpose of retouching, though he also says

that the alcohol was kept in store and not in

the bodega where the furniture was. It is well settled

that the keeping of inflammable oils on the

premises, though prohibited by the policy, does not

void it if such keeping is incidental to the business

insurer CANNOT avoid payment of loss, though

the keeping of benzene is expressly prohibited.

It may be added that there was no provision in the

policy prohibiting the keeping of paints and

varnishes upon the premises where the insured

property was stored. If the company intended to rely

upon a condition of that character, it ought to have

been plainly expressed in the policy.

It does not positively appear of record that the

automobile in question was not included in the other

policies. It does appear that the automobile was

saved and was considered as a part of the salvaged.

It is alleged that the salvage amounted to P4,000,

including the automobile. This amount (P4,000) was

distributed among the different insurers and the

amount of their responsibility was proportionately

reduced. The defendant and appellant in the present

case made no objection at any time in the lower

court to that distribution of the salvage. The claim is

now made for the first time. No reason is given why

the objection was not made at the time of the

distribution of the salvage, including the automobile,

among all of the insurers.

The petitioner is the owner of Norman's Mart

located in the public market of San Francisco,

Agusan del Sur. On 22 December 1989, he obtained

from the private respondent fire insurance policy for

P100,000.00. The period of the policy was from 22

December 1989 to 22 December 1990 and covered

the following: "Stock-in-trade consisting principally

of dry goods such as RTW's for men and women

wear and other usual to assured's business."

The petitioner declared in the policy under the

subheading entitled CO-INSURANCE that Mercantile

Insurance Co., Inc. was the co-insurer for

P50,000.00. From 1989 to 1990, the petitioner had

in his inventory stocks amounting to P392,130.50.

A fire of accidental origin broke out at around 7:30

p.m. at the public market of San Francisco, Agusan

del Sur. The petitioner's insured stock-in-trade were

completely destroyed prompting him to file with

the private respondent a claim under the policy. On

28 December 1990, the private respondent denied

the claim because it found that at the time of the

loss the petitioner's stocks-in-trade were likewise

covered by fire insurance policies No. GA-28146

and No. GA-28144, for P100,000.00 each, issued by

the Cebu Branch of the Philippines First Insurance

3

Co., Inc. (hereinafter PFIC). These policies indicate

that the insured was "Messrs. Discount Mart (Mr.

Armando Geagonia, Prop.)" WITH A MORTGAGE

CLAUSE:

MORTGAGE: Loss, if any shall be payable to Messrs.

Cebu Tesing Textiles, Cebu City as their interest

may appear subject to the terms of this policy. COINSURANCE DECLARED: P100,000

The basis of the private respondent's denial was the

petitioner's alleged violation of Condition 3 of the

policy.

COMPLAINT.Petitioner filed a complaint against

respondent w/ the Insurance Commission for the

recovery of P100,000.00 under the fire insurance

policy.

RULING: JUDGMENT AFFIRMED.

GEAGONIA v CA

FACTS:

CONTENTION OF PETITIONER: No knowledge of the

provisions in the COI that he needed to inform the

insurer of the prior policies; the said reqt was NOT

mentioned to him by the private respondents agent

INSURANCE COMMISSION: Pay P100,000.00.

Petitioner did NOT violate the said Condition as he

had no knowledge of the existence of the two fire

insurance policies obtained from the PFIC; that it

was Cebu Tesing Textiles which procured the PFIC

policies without informing him or securing his

consent; and that Cebu Tesing Textile, as his

creditor, had insurable interest on the stocks.

Petitioner came to know of the PFIC policies only

when he filed his claim with the private respondent

and that Cebu Tesing Textile obtained them and

paid for their premiums without informing him

thereof.

CA: Reversed; petitioner knew of the existence of

the 2 other policies issued by PFIC: the insurance

was taken in the name of private respondent

[petitioner herein]. The policy states that "DISCOUNT

MART (MR. ARMANDO GEAGONIA, PROP)" was the

assured and that "TESING TEXTILES" [was] only the

mortgagee of the goods.

The premiums on both policies were paid for by

private respondent, not by the Tesing Textiles which

is alleged to have taken out the other insurance

without the knowledge of private respondent. In

both invoices, Tesing Textiles is indicated to be only

the mortgagee of the goods insured but the party

to which they were issued were the "DISCOUNT

MART (MR. ARMANDO GEAGONIA)."

ISSUES:

(a) Whether the petitioner had prior knowledge of

the two insurance policies issued by the PFIC when

he obtained the fire insurance policy from the

private respondent, thereby, for not disclosing such

fact, violating Condition 3 of the policy, and (b) if he

had, whether he is precluded from recovering

therefrom.

HELD:

1. The SC agreed w/ CA. His letter of 18 January 1991

to the private respondent conclusively proves this

knowledge. His testimony to the contrary before the

Insurance Commissioner and which the latter relied

upon cannot prevail over a written admission

made ante litem motam. It was, indeed, incredible

that he did not know about the prior policies since

these policies were not new or original. Policy No.

GA-28144 was a renewal of Policy No. F-24758,

while Policy No. GA-28146 had been renewed

twice, the previous policy being F-24792.

NOTE: Condition 3 is NOT proscribed by law. This is

allowed by the Insurance Code which provides that

"[a] policy may declare that a violation of specified

provisions thereof shall avoid it, otherwise the

breach of an immaterial provision does not avoid the

policy." Such a condition is a provision which

invariably appears in fire insurance policies and is

intended to prevent an increase in the moral hazard.

It is commonly known as the additional or "other

insurance" clause and has been upheld as valid and

as a warranty that no other insurance exists. Its

violation

would

thus

avoid

the

policy.

In order to constitute a violation, the other

insurance MUST be upon same subject matter, the

same interest therein, and the same risk.

MORTGAGE. As to a mortgaged property, the

mortgagor and the mortgagee have each an

independent insurable interest therein and both

interests may be one policy, or each may take out a

separate policy covering his interest, either at the

18

same or at separate times. The mortgagor's

insurable interest covers the full value of the

mortgaged property, even though the mortgage

debt is equivalent to the full value of the

19

property. The mortgagee's insurable interest is to

the extent of the debt, since the property is relied

upon as security thereof, and in insuring he is not

insuring the property but his interest or lien

thereon. His insurable interest is prima facie the

value mortgaged and extends only to the amount

of the debt, not exceeding the value of the

20

mortgaged property. Thus, separate insurances

covering different insurable interests may be

obtained by the mortgagor and the mortgagee.

A mortgagor may, however, take out insurance for

the benefit of the mortgagee, which is the usual

practice. The mortgagee may be made the beneficial

payee in several ways. He may become the

ASSIGNEE of the policy with the consent of the

insurer; or the mere PLEDGEE without such consent;

or the original policy may contain a mortgage clause;

or a rider making the policy payable to the

mortgagee "as his interest may appear" may be

attached; or a "standard mortgage clause,"

containing a collateral independent contract

between the mortgagee and insurer, may be

attached; or the policy, though by its terms payable

absolutely to the mortgagor, may have been

procured by a mortgagor under a contract duty to

insure for the mortgagee's benefit, in which case

the mortgagee acquires an equitable lien upon the

proceeds,

IN CASE AT BAR: In the policy obtained by the

mortgagor with loss payable clause in favor of the

mortgagee as his interest may appear, the

MORTGAGEE IS ONLY A BENEFICIARY under the

contract, and recognized as such by the insurer but

NOT made a party to the contract himself. Hence,

any act of the mortgagor which defeats his right

22

will also defeat the right of the mortgagee. This

kind of policy covers only such interest as the

23

mortgagee has at the issuing of the policy.

On the other hand, a mortgagee may also procure a

policy as a contracting party in accordance with the

terms of an agreement by which the mortgagor is

24

to pay the premiums upon such insurance. It has

been noted, however, that although the mortgagee

is himself the insured, as where he applies for a

policy, fully informs the authorized agent of his

interest, pays the premiums, and obtains on the

assurance that it insures him, the policy is in fact in

the form used to insure a mortgagor with loss

payable clause.

The fire insurance policies issued by the PFIC name

the petitioner as the assured and contain a

mortgage clause: Loss, if any, shall be payable to

MESSRS. TESING TEXTILES, Cebu City as their interest

may appear subject to the terms of this policy.

This is clearly a simple loss payable clause,

NOT a standard mortgage clause.

CARDINAL RULE: It is to be interpreted liberally in

favor of the insured and strictly against the

company, the reason being, undoubtedly, to afford

the greatest protection which the insured was

endeavoring to secure when he applied for

insurance. It is also a cardinal principle of law that

forfeitures are not favored and that any

construction which would result in the forfeiture of

the policy benefits for the person claiming

thereunder, will be avoided, if it is possible to

construe the policy in a manner which would permit

recovery, as, for example, by finding a waiver for

such forfeiture.

ERGO, Condition 3 of the subject policy is NOT

totally free from ambiguity and must, perforce, be

meticulously analyzed. Such analysis leads us to

conclude that (a) the prohibition applies only to

double insurance, and (b) the nullity of the policy

shall only be to the extent exceeding P200,000.00

of the total policies obtained.

DOUBLE INSURANCE. The first conclusion is

supported by the portion of the condition referring

to other insurance "covering any of the property or

properties consisting of stocks in trade, goods in

process and/or inventories only hereby insured,"

and the portion regarding the insured's declaration

on the subheading CO-INSURANCE that the coinsurer is Mercantile Insurance Co., Inc. in the sum of

P50,000.00.

A double insurance exists where the same person is

insured by several insurers separately in respect of

the same subject and interest. As earlier stated, the

insurable interests of a mortgagor and a mortgagee

on the mortgaged property are distinct and

separate. Since the two policies of the PFIC do not

cover the same interest as that covered by the

policy of the private respondent, no double

insurance exists. The non-disclosure then of the

former policies was NOT fatal to the petitioner's

right to recover on the private respondent's policy.

OVERINSURANCE. Condition 3 itself that such

condition shall not apply if the total insurance in

force at the time of loss does not exceed

P200,000.00, the private respondent was amenable

to assume a co-insurer's liability up to a loss not

exceeding P200,000.00. What it had in mind was to

discourage over-insurance. Indeed, the rationale

behind the incorporation of "other insurance" clause

in fire policies is to prevent over-insurance and thus

avert the perpetration of fraud.

EFFECT: When a property owner obtains

insurance policies from two or more

insurers in a total amount that exceeds the

property's value, the insured may have an

inducement to destroy the property for the

purpose of collecting the insurance. The

public as well as the insurer is interested in

preventing a situation in which a fire would

be profitable to the insured.

RULING: GRANTED. INSURANCE

DECISION REINSTATED.

COMMISSION

UNITED MERCHANTS CORP. v COUNTRY BANKERS

INSURANCE

used by the Insured or anyone acting in his behalf to

obtain any benefit under this Policyshall be

forfeited.

COMPLAINT. Filed a complaint before the RTC of

Manila w/ a cert. from the Fire Bureau

FACTS:

RTC: in favor of plaintiff

Petitioner United Merchants Corporation (UMC) is

engaged in the business of buying, selling, and

manufacturing Christmas lights. UMC leased a

warehouse at 19-B Dagot Street, San Jose

Subdivision, Barrio Manresa, Quezon City, where

UMC assembled and stored its products.

CA: reversed; fire was intentional hence, policy was

void.

UMCs General Manager Alfredo Tan insured UMCs

stocks in trade of Christmas lights against fire with

defendant Country Bankers Insurance Corporation

(CBIC) for P15,000,000.00. The Fire Insurance Policy

No. F-HO/95-576 (Insurance Policy) and Fire Invoice

No. 12959A, valid until 6 September 1996.

HELD:

UMC and CBIC executed Endorsement F/96-154 and

Fire Invoice No. 16583A to form part of the

Insurance Policy. Endorsement F/96-154 provides

that UMCs stocks in trade were insured against

additional perils, to wit: "typhoon, flood, ext. cover,

and full earthquake." The sum insured was also

increased toP50,000,000.00 effective 7 May 1996 to

10 January 1997. On 9 May 1996, CBIC issued

Endorsement F/96-157 where the name of the

assured was changed from Alfredo Tan to UMC.

FIRE. A fire gutted the warehouse rented by UMC.

CBIC designated CRM Adjustment Corporation (CRM)

to investigate and evaluate UMCs loss by reason of

the fire. CBICs reinsurer, Central Surety, likewise

requested the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI)

to conduct a parallel investigation. On 6 July 1996,

UMC, through CRM, submitted to CBIC its Sworn

Statement of Formal Claim, with proofs of its loss.

CLAIM. On 20 November 1996, UMC demanded for

at least fifty percent (50%) payment of its claim from

CBIC. On 25 February 1997, UMC received CBICs

letter, dated 10 January 1997, rejecting UMCs claim

due to breach of Condition No. 15 of the Insurance

Policy. Condition No. 15 states:

If the claim be in any respect fraudulent, or if any

false declaration be made or used in support

thereof, or if any fraudulent means or devices are

ISSUE: Whether UMC is entitled to claim from CBIC

the full coverage of its fire insurance policy.

In the present case, CBICs evidence did not prove

that the fire was intentionally caused by the

insured. First, the findings of CBICs witnesses,

Cabrera and Lazaro, were based on an investigation

conducted more than four months after the fire. The

testimonies of Cabrera and Lazaro, as to the boxes

doused with kerosene as told to them

by barangay officials,

are

hearsay

because

the barangay officials were not presented in court.

Cabrera and Lazaro even admitted that they did not

conduct a forensic investigation of the warehouse

28

nor did they file a case for arson. Second, the

Sworn Statement of Formal Claim submitted by

UMC, through CRM, states that the cause of the fire

was "faulty

electrical

wiring/accidental

in

nature." CBIC is bound by this evidence because in

its Answer, it admitted that it designated CRM to

evaluate UMCs loss. Third, the Certification by the

Bureau of Fire Protection states that the fire was

accidental in origin.

In the present case, arson and fraud are two

separate grounds based on two different sets of

evidence, either of which can void the insurance

claim of UMC. The absence of one does not

necessarily result in the absence of theother. Thus,

on the allegation of fraud, we affirm the findings of

the Court of Appeals.

Condition No. 15 of the Insurance Policy provides

that all the benefits under the policy shall be

forfeited, if the claim be in any respect fraudulent, or

if any false declaration be made or used in support

thereof, to wit:

policy. Mere filing of such a claim will exonerate the

insurer.

15. If the claim be in any respect fraudulent, or if any

false declaration be made or used in support

thereof, or if any fraudulent means or devices are

used by the Insured or anyone acting in his behalf to

obtain any benefit under this Policy; or if the loss or

damage be occasioned by the willful act, or with the

connivance of the Insured, all the benefits under this

Policy shall be forfeited.

Considering that all the circumstances point to the

inevitable conclusion that UMC padded its claim and

was guilty of fraud, UMC violated Condition No. 15

of the Insurance Policy. Thus, UMC forfeited

whatever benefits it may be entitled under the

Insurance Policy, including its insurance claim.

INVOICES NOT GENUINE. The invoices, however,

cannot be taken as genuine. The invoices reveal that

the stocks in trade purchased for 1996 amounts

to P20,000,000.00 which were purchased in one

month. Thus, UMC needs to prove purchases

amounting to P30,000,000.00 worth of stocks in

trade for 1995 and prior years. However, in the

Statement of Inventory it submitted to the BIR,

which is considered an entry in official

34

records, UMC stated that it had no stocks in trade

as of 31 December 1995. In its defense, UMC alleged

that it did not include as stocks in trade the raw

materials to be assembled as Christmas lights, which

it had on 31 December 1995. However, as proof of

its loss, UMC submitted invoices for raw materials,

knowing that the insurance covers only stocks in

trade.

NOTE: It has long been settled that a false and

material statement made with an intent to deceive

42

or defraud voids an insurance policy. In Yu Cua v.

43

South British Insurance Co., the claim was fourteen

times bigger than the real loss; in Go Lu v. Yorkshire

44

Insurance Co, eight times; and in Tuason v. North

45

China Insurance Co., six times. In the present case,

the claim is twenty five times the actual claim

proved. there was DELIBERATE intent to demand

from insurer payment for indemnity of goods NOT

existing at the time of the fire.

On UMCs allegation that it did not breach any

warranty, it may be argued that the discrepancies do

not, by themselves, amount to a breach of warranty.

However, the Insurance Code provides that "a

policy may declare that a violation of specified

49

provisions thereof shall avoid it." Thus, in fire

insurance policies, which contain provisions such as

Condition No. 15 of the Insurance Policy, a

fraudulent discrepancy between the actual loss and

that claimed in the proof of loss voids the insurance

RULING: PETITION DENIED.

Você também pode gostar

- Eminent Domain and TaxationDocumento11 páginasEminent Domain and TaxationErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- NUISANCE CANDIDATE DISQUALIFICATIONDocumento29 páginasNUISANCE CANDIDATE DISQUALIFICATIONErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Appeal CasesDocumento25 páginasAppeal CasesErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Crim DigestDocumento4 páginasCrim DigestErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Land ownership dispute case between competing claimsDocumento5 páginasLand ownership dispute case between competing claimsErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Action in Case of BreachDocumento25 páginasAction in Case of BreachErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- RecallDocumento18 páginasRecallErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Estate Settlement Venue and Capacity RulesDocumento2 páginasEstate Settlement Venue and Capacity RulesNap GonzalesAinda não há avaliações

- Recall 1Documento30 páginasRecall 1Erica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Arogante V DeliarteDocumento5 páginasArogante V DeliarteErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Credit CasesDocumento8 páginasCredit CasesErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Sem 3Documento7 páginasSem 3Erica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Wages CasesDocumento23 páginasWages CasesErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Land ownership dispute case between competing claimsDocumento5 páginasLand ownership dispute case between competing claimsErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- LTD CasesDocumento8 páginasLTD CasesErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Military Court Martial Proceedings Regarding 1989 CoupDocumento4 páginasMilitary Court Martial Proceedings Regarding 1989 CoupErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Insurrection, Have Created A State ofDocumento9 páginasInsurrection, Have Created A State ofErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- CONSTI 2 ReviewerDocumento30 páginasCONSTI 2 ReviewerMaria Diory Rabajante100% (43)

- Code of Professional ResponsibilityDocumento7 páginasCode of Professional ResponsibilityKatherine Aplacador100% (1)

- Incapacity Case DigestsDocumento2 páginasIncapacity Case DigestsErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Extinguishment of Sale1Documento17 páginasExtinguishment of Sale1Erica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Accommodation Party CasesDocumento4 páginasAccommodation Party CasesErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Republic vs. Lim DigestDocumento2 páginasRepublic vs. Lim DigestMara Odessa Ali100% (1)

- Ex Post FactoDocumento7 páginasEx Post FactoErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Small Voices. Heavenly Praises: Molino Unida Christian FellowshipDocumento1 páginaSmall Voices. Heavenly Praises: Molino Unida Christian FellowshipErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Wala Kang Katulad ChordsDocumento1 páginaWala Kang Katulad ChordsErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- What Can Be Said of Education? Declare That ProclaimDocumento2 páginasWhat Can Be Said of Education? Declare That ProclaimErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Due Process and Equal ProtectionDocumento11 páginasDue Process and Equal ProtectionErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Right of ConfrontationDocumento2 páginasRight of ConfrontationErica NolanAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- 135 Babst V. National Intelligence Board FactsDocumento1 página135 Babst V. National Intelligence Board Factsadee0% (1)

- BetweenDocumento13 páginasBetweenBrian ChukwuraAinda não há avaliações

- Life and Works of P.N.Bhagwati: Hidayatullah National Law University Uparwara, New Raipur, C.GDocumento16 páginasLife and Works of P.N.Bhagwati: Hidayatullah National Law University Uparwara, New Raipur, C.GSaurabh BaraAinda não há avaliações

- Ex Parte Order PDFDocumento2 páginasEx Parte Order PDFAliciaAinda não há avaliações

- Rights of The Accused CasesDocumento108 páginasRights of The Accused CasesMaginarum MamiAinda não há avaliações

- IPay Clearing Services Private Limited V ICICI Bank LimitedDocumento21 páginasIPay Clearing Services Private Limited V ICICI Bank LimitedArunjeet SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Order Denying Defendant's Motion To DismissDocumento7 páginasOrder Denying Defendant's Motion To DismissDavid GrecoAinda não há avaliações

- Better Mouse Company v. Giga-Byte Technology Et. Al.Documento5 páginasBetter Mouse Company v. Giga-Byte Technology Et. Al.PriorSmartAinda não há avaliações

- Lim Vs LazaroDocumento2 páginasLim Vs LazaroeAinda não há avaliações

- Torts Battery Essay OutlineDocumento5 páginasTorts Battery Essay OutlineKMAinda não há avaliações

- Conciliation: About The Conciliation ProcessDocumento2 páginasConciliation: About The Conciliation ProcessSuleimanRajabuAinda não há avaliações

- People vs. Simon, G.R. No. 93028Documento17 páginasPeople vs. Simon, G.R. No. 93028LASAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Terminologies in Business LawDocumento13 páginasLegal Terminologies in Business LawAlberto NicholsAinda não há avaliações

- 7 Peltan Development VS CaDocumento2 páginas7 Peltan Development VS CaRonnie Garcia Del RosarioAinda não há avaliações

- Ale Lie Position PaperDocumento19 páginasAle Lie Position PaperAlelie BatinoAinda não há avaliações

- Distinction of Actions For Recovery of PropertyDocumento2 páginasDistinction of Actions For Recovery of PropertyZyrel Joy C. ZARAGOSAAinda não há avaliações

- Election Protest Decision SampleDocumento14 páginasElection Protest Decision SampleMailyn Castro-VillaAinda não há avaliações

- Belgian Overseas v. Phil First InsuranceDocumento1 páginaBelgian Overseas v. Phil First InsuranceRain HofileñaAinda não há avaliações

- Everett Steamship Corporation Case DigestDocumento2 páginasEverett Steamship Corporation Case Digestalexredrose0% (1)

- Civ2 1st Half 2017 CasesDocumento160 páginasCiv2 1st Half 2017 CasesAudreyAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Court Documents Object to Evidence in Drug CasesDocumento4 páginasPhilippine Court Documents Object to Evidence in Drug CasesDraei DumalantaAinda não há avaliações

- Topic: Consent Freely Given Acts: Case Facts Issues RulingDocumento1 páginaTopic: Consent Freely Given Acts: Case Facts Issues RulingA M I R AAinda não há avaliações

- Sanatan Pandey Vs State of Uttar Pradesh LL 2021 SC 568 1 402290 PDFDocumento5 páginasSanatan Pandey Vs State of Uttar Pradesh LL 2021 SC 568 1 402290 PDFArmaan SidAinda não há avaliações

- Contract Assignment - Incapacity To ContractDocumento17 páginasContract Assignment - Incapacity To Contractaditf14100% (3)

- People - S Broadcasting v. SecretaryDocumento2 páginasPeople - S Broadcasting v. SecretaryRaymund CallejaAinda não há avaliações

- MOD 11 and 12Documento16 páginasMOD 11 and 12Frances Rexanne AmbitaAinda não há avaliações

- BILL No. 27 of 2021 TNDocumento4 páginasBILL No. 27 of 2021 TNMala deviAinda não há avaliações

- Group 4 Final Case DigestDocumento17 páginasGroup 4 Final Case DigestRewsEnAinda não há avaliações

- Philippines Supreme Court Case on Compensability of School Principal's DeathDocumento6 páginasPhilippines Supreme Court Case on Compensability of School Principal's DeathSheena ValenzuelaAinda não há avaliações

- LicenseDocumento2 páginasLicenseahadwebAinda não há avaliações