Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Residuary Powers of Legislation

Enviado por

Christina ShajuTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Residuary Powers of Legislation

Enviado por

Christina ShajuDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

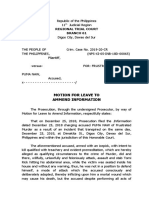

NATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY,

BHOPAL

In partial fulfilment of the requirement of the project on the subject of Constitutional Law-III

of B.A., L.L.B (Hons.), Fifth Trimester

ACADEMIC YEAR: 2015-16

Submitted on 5th November 2015

Residuary Powers of Legislation in the Indian Constitution and a

Comparative Study of other Federal Constitutions of the World

Submitted to:

Ms. Kuldeep Kaur

Barrister-at-Law,

Lincoln's Inn, London.

Submitted by:

Udyan Arya Shrivastava

(2014 BALLB 98)

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

On completion of this Project it is my present privilege to acknowledge my profound gratitude

and indebtedness towards my teachers for their valuable suggestions and constructive criticism.

Their precious guidance and unrelenting support kept me on the right track throughout the

project. I gratefully acknowledge my deepest sense of gratitude to:

Prof. (Dr.) S.S. Singh, Director, National Law Institute University, Bhopal for providing us with

the infrastructure and the means to make this project;

Our Constitutional Law teacher, Ms. Kuldeep Kaur, who provided me this wonderful

opportunity and guided me throughout the project work;

Im also thankful to the library and computer staffs of the University for helping me find and

select books from the University library.

Finally, Im thankful to my family members and friends for the affection and encouragement

with which doing this project became a pleasure.

Udyan Arya Shrivastava

(2014 BALLB 98)

[2]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1) TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. 3

2) INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 4

a) THE NATURE OF RESIDUARY POWER ....................................................................................... 4

3) RESIDUARY POWERS CLAUSE IN THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION ................ 5

a) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT, 1935 AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF LEGISLATIVE POWERS . 5

b) VESTING OF RESIDUARY POWERS .............................................................................................. 7

c) SCOPE OF RESIDUARY POWER ..................................................................................................... 7

4) PROVISIONS FOR RESIDUARY LEGISLATIVE POWERS IN OTHER

FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONS OF THE WORLD .................................................... 9

a)

b)

c)

d)

U.S.A. .............................................................................................................................................. 9

CANADA ........................................................................................................................................ 11

AUSTRALIA.................................................................................................................................... 12

SWITZERLAND .............................................................................................................................. 13

5) CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................ 14

6) BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 15

a) BOOKS ........................................................................................................................................... 15

b) WEBSITES ...................................................................................................................................... 15

[3]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

INTRODUCTION

The Constitution of India, enacted in 1950, is of relatively recent origin and artificial

construction when compared with the constitutions of other leading federations of the world.

Most of the provisions of the Constitution, especially those dealing with the federal structure and

distribution of legislative powers, are based not on shared experiences in the working of a

republic but were drafted by the Constituent Assembly after studying the constitutions of other

leading federations of the world.

The nature of Residuary Power

One of the hallmarks of the federal system is distribution of legislative powers between the

centre and the states (or federating units). This distribution of legislative powers can lead to

unforeseen circumstances as it is humanly not possible to foresee every possible activity and

assign it to one List or the other. In such circumstances the question of residuary powers arises.

Who will have the legislative competence to legislate on residual subjects, i.e., subjects not

mentioned in any of the Lists? It is quite impossible for constitution makers to provide an

exhaustive list of powers: something is bound to be forgotten or new fields of jurisdiction are

likely to appear in the future. Thus, it becomes necessary to provide some blanket clause which

will determine which of the two levels of government shall get those new powers. Most federal

constitutions of the world envisage such a difficulty and make a special provision for either the

centre or the states to legislate on residuary matters. This provision is known as the residuary

powers clause and such power to legislate is known as residuary legislative power.

In this project Ill attempt to dissect the residuary powers clause in the Indian Constitution,

understand its scope and then undertake a comparative study with other leading federal

constitutions of the world, namely U.S.A., Australia, Canada and Switzerland.

[4]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

RESIDUARY POWERS CLAUSE IN THE INDIAN

CONSTITUTION

Article 248 of the Indian Constitution, which vests residuary power in the Parliament, states,

248. Residuary powers of legislation.

(1) Parliament has exclusive power to make any law with respect to any matter not

enumerated in the Concurrent List or State List.

(2) Such power shall include the power of making any law imposing a tax not mentioned in

either of those Lists.

To fully understand this provision its important to appreciate its context and evolution, which is

discussed as follows.

Government of India Act, 1935 and the Distribution of Legislative Powers

The federal scheme in the Constitution of India is adopted from the Government of India Act,

1935. The said Act made an innovation upon several precedents to make a treble enumeration of

powers, in order to make it as exhaustive as possible and also to minimize judicial intervention

and litigation. The three legislative lists (I, II and III) respectively enumerated the powers vested

in the Federal Legislature, the Provincial Legislature and to both of them concurrently (Section

100). If however, a matter was not covered by any of the three Lists that would be treated as a

residuary power of the Federal Parliament (Section 104) and Section 107 provided for

predominance of federal law in case of inconsistency with a Provincial Law, in the concurrent

sphere.1

Thus, under the Government of India Act, 1935, the residuary power of legislation was given

neither to the Federal Legislature nor to the provincial legislatures. It was left to the discretion of

the Governor-General to assign these powers to either Legislature. It was only when all

categories in the three Lists were absolutely exhausted that one could think of falling back upon

the residuary powers.2 But the Lists under the Act were so exhaustive that they left little or

nothing in the residuary field. It is to be noted that the only reported occasion for the application

1

2

Re. C.P. Motor Spirit Taxation, AIR 1939 FC 1(5); Prafulla v. Bank of Commerce, (1947) 51 CWN 599 (610) (PC).

Governor- General v. Province of Madras, AIR 1945 PC 98: 1945 FCR 179.

[5]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

of the residuary power of the legislation under the Government of India Act, 1935 was as

regards the power to provide for acquisition of a commercial or industrial undertaking.3

Borrowing the pattern of treble enumeration from the Government of India Act, 1935, the

Constitution of India makes a three-fold division of powers namely;

a) List I or the Union List It contains subjects over which the Union shall have exclusive

powers of legislation, including 97 items. These include defence, foreign affairs,

banking, currency and coinage; union duties and taxes and the like.

b) List II or the State List It comprises of 66 items or entries over which the State

Legislature shall have exclusive power of legislation, such as public order and police,

local Government, public health and sanitation, agriculture, forests and fisheries,

education, State taxes and duties, and the like.

c) List III or the Concurrent List It gives concurrent powers to the Union and the State

Legislatures over 47 items, such as Criminal Law and procedure, Civil Procedure,

marriage, contracts, torts, trusts, welfare of labour, social insurance, economic and

social planning.

Thus the framers of the Indian Constitution attempted to exhaust the whole field of legislation

as they could comprehend, into numerous items, narrowing down the scope for filling up the

details by the judicial process of amplifying the given items. Besides, wherever any conflict could

be anticipated, the Constitution has given predominance to the Union jurisdiction, so as to give

the federal system a strong central bias. Similarly, in all the cases which have come up to the

Supreme Court, the Court has upheld the jurisdiction of the Union Parliament. Thus, in case of

overlapping, the power of the State Legislature to legislate with respect to matters enumerated in

the State List has been made subject to the power of the Union Parliament to legislate in respect

of matters enumerated in the Union and Concurrent Lists, and the entries in the State List have

to be interpreted accordingly.4 Similarly, in the concurrent sphere, in case of repugnancy between

a Union and a State law relating to the same subject, the former prevails. If, however, the State

law was reserved for the assent of the President and has received such assent, the State law may

Rajahmundry Electric Supply Co. v. State of Andhra, (1954) S.C.A. 272.

K.S.E.Bd. v. Indian Aluminium, AIR 1976 SC 1031 (1036-37); I.T.C. v. State of Karnataka, (1985) Supp SCC 476

(para. 19).

3

4

[6]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

prevail notwithstanding such repugnancy, but it would still be competent for Parliament to

override such State law by subsequent legislation {Article 254(2)}.5

Vesting of Residuary Powers

The Constitution of India vests the residuary power, i.e., the power to legislate with respect to

any matter not enumerated in anyone of the three Lists, in the Union Legislature (Article 248).

The vesting of residual power under the Constitution follows the precedent of Canada, for it is

given to the Union instead of the States as in USA and Australia.

Our Constitution has bodily adopted the concept of Residuary Powers of the Legislation from

the scheme of Government of India Act, 1935.In India the residuary powers of the legislation

have been vested in the Centre so as to incline towards the fabric of the Indian federal system

which thus makes the Centre stronger. As was stated in the Constituent Assembly by Pt. Jawahar

Lal Nehru, Chairman of the Union Powers Committee:

We think that Residuary Powers should remain with the Centre. In view of the

exhaustive nature of the three lists drawn upon by us, the residuary subjects could only

relate to matters which, while they may claim recognition in future are not identifiable and

cannot be included now in the Lists.6

Although under the present Constitution, the scheme of the Three Lists has been taken over

with the difference that although the three lists has been greatly enlarged and is made exhaustive

in nature, but the residue power has been conferred on the centre. In adopting the scheme of the

Government of India Act, 1935 our Constitution had the benefit of the innovations which the

Act had introduced in the distribution of legislative power as the lists contained very little

overlapping of issues.

However, the final determination as to whether a particular matter falls under the residuary

power or not is that of the Courts.7

Scope of Residuary Power

It can be easily pointed out that the aim of the Indian Constitution, like that of the Government

of India Act, 1935, is to make the Legislative Lists as exhaustive as possible. The three lists

U.P.E.S. v. Shukla, AIR 1970 SC 237(239).

B. Shiva Rao, The Framing of Indias Constitution, Vol. II, p. 777.

7 Union of India v. Dhillon, AIR 1972 SC 1061.

5

6

[7]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

which were exhaustive as to leave little or nothing for the residual field was said for the

Government of India Act, 1935 is even more pertinent to the present Constitution as it contains

97 as against 59 entries in the List I, 66 entries as against 54 in list II and even List III is larger in

the present Constitution. Hence, the resort to the residual power should be the last refuge was

held for Government of India Act, 1935 still prevails with the present Constitution.

In a case where two constructions are possible, one of which will avoid resort to the residuary

power and the other which will necessitate such resort, the former must be preferred. This does

not mean, however, that in order to avoid falling back upon the residual power, the Court would

be justified in straining the language of any of the Entries or to render the residuary entry

altogether meaningless. This article, i.e., Art. 248(1) applies to the Union vis a vis the States. So

far as the Union Territories are concerned, Parliament has unlimited power under the article 246

(4). Nonetheless great care with which the various Entries in the three lists given under the

seventh schedule of our Constitution have been framed, there may be some legislative or taxing

power which does not come under any of these Entries. In such a case, it is the Union

Parliament which shall have the power to legislate with regard to such matter of taxation, by

virtue of Art. 248(2). Art 248(2) has reference to the distribution of legislative powers between

the centre and the states as it provides that in respect of matters not enumerated in the Lists

including taxation. It is the Parliament that has power to enact laws for which provision is given

under Art. 248(2) read with Art. 246(4) of the Indian Constitution. This Residuary Power of

legislation has also been explained in Entry 97 of the Union List (List I) as follows:

Any other matter not enumerated in List II or List III including any tax

not mentioned in either of those Lists.

[8]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

PROVISIONS FOR RESIDUARY LEGISLATIVE POWERS

IN OTHER FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONS OF THE WORLD

U.S.A.

In USA, there is a single enumeration of powers, which signifies that the Constitution simply

enumerates the powers specially assigned to the Federal Legislature and leaves the entire

unremunerated residue to the State Legislatures. Woodrow Wilson stated that the State

Governments are the ordinary governments of the country; the federal government is its

instrument only for the particular purposes.8 The Constitution of the USA makes the division

of powers between the Federation and the States by the following four provisions:

1. Powers of the Union - The Federal Congress has no general power to make laws for the

people; it has got only enumerated powers. These powers are enumerated in Article. I, Section 8

to declare war, raise armies, coin money, regulate foreign commerce etc. As to the powers of the

national government, Marshall, C.J. said in the case of Gibbons v. Ogden9 that the genius and

character of the whole government seem to be, that its action is to be applied to all the external

concerns of the nation, and to those internal concerns which affect the States generally, but not

to those which are completely within a particular State, which do not affect other States, and

with which it is not necessary to interfere for the purpose of executing some of the general

powers of the national Government

2. Powers of the States The powers of the States are not enumerated by the Constitution.

However, according to the Tenth Amendment, the powers not delegated to the United States by

the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or the

people. Thus, the residuary powers are given to the States. The reserved rights of the States inter

alia includes the right to pass laws, to give effect to laws through executive action, to administer

justice through the Courts, and to employ all necessary agencies for legitimate purposes of State

Government.

3. Limitations on Union Powers Congress is prohibited from taxing exports or giving

preference to particular States in the exercise of its Commerce powers, namely; No Tax or

Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State and no preference shall be given by any

8

9

Woodrow Wilson, Constitutional Government, quoted in New York v. United States, (1946) 326 US 572 (592).

(1824) 9 Wh (195).

[9]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

Regulation of Commerce or Revenue to the Ports of one State over those of another, nor shall

Vessels bound to or from, one State, be obliged to enter, clear or pay Duties in another by

Clauses. (5) and (6) of Article I, Section 9 respectively.

4. Limitation on States Powers Though all powers not expressly given to the Union were

reserved to the States (10th Amendment), the Constitution at the same time imposed certain

limitations upon the exercise of those reserved powers so that their exercise might not interfere

with the exercise of the powers conferred upon the National Government. These limitations are:

a. Taxation No State may, without the consent of Congress, lay any tax on tonnage or on

imports and exports beyond what may be necessary for enforcing its inspection laws

under Article I, Section 10(3) and Section 10(2) respectively.

b. Monetary Under Article 1 Section 10(1), no State shall coin money, emit bills of credit;

make anything but gold and silver coin a tender in payment of debts. Thus, the power

over currency and coin given to the National Government is exclusive.10 Actually, it is

essential in the commercial and economic interests of the Union to have a uniform

monetary system.

c. Foreign and Inter-State Agreements As per Article I, Section 10 no State shall enter

into any treaty or confederation..No State shall, without the consent of Congress, enter

into any agreement or compact with another State or with a foreign power. The

prohibition against foreign agreements supplements the provisions regarding treaties

{Article II, Section 2(2)} in favour of the National Government. The power is made

exclusive by prohibiting the States to enter into that field11 and the prohibition against the

inter-State compacts without the consent of Congress is, obviously, meant to prevent the

growth of political combinations which may encroach upon the supremacy of the United

States.12 In practice, however, the Clause has made possible inter-state co-operation on

common problems with the approval of the National Government.

Subject to the above limitations, the States have full sovereign powers over all persons and things

within their respective territorial limits with respect to all matters which are not delegated to

Congress by the Constitution, expressly or by necessary implication.13

University of Illinois v. U.S., (1933) 289 US 48.

Ibid.

12 Virginia v. Tennessee, (1893) 148 US 503.

13 Carter v. Cater Coal Co., (1936) 298 US 238.

10

11

[ 10 ]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

Thus, there is no Concurrent List in the American Constitution. However, a concurrent sphere

has resulted from the judicial interpretation that there is a sphere, where a State can legislate so

long as Congress does not occupy the field or the State legislation does not conflict with a

federal legislation.14 Nevertheless, it seems that each government, national and State, is supreme

within their own sphere. In other words neither Government can exercise its powers in such

manner as to obstruct the free exercise of power by another.

The position on paper today is that Congress itself cannot under any device; exercise any power

which is not granted to it expressly or by necessary implication. But the area of concern is

implied power founded inter alia, upon the necessary and proper clause clause in Article I,

Section 8(18) which signifies that the Courts have helped in the expansion of the federal power

to an extent undreamt of by the fathers of the Constitution and hence the Congress may legislate

on matters under the pretext of necessary and proper which though not comes under their

domain.

Canada

In Canada, the residuary powers were allocated to the federal government. The Fathers of

Confederation wanted to avoid the "weaknesses" of the American constitution which had left all

residual powers in the hands of the constituting states. The conditions prevalent in British North

America, at the time of Confederation seemed to dictate the creation of a strong federal

government endowed with sufficiently large powers to withstand American pressures and create

a strong national economy. Residuary powers would assure, in the future, the continued strength

of the Dominion government.

In a strict sense the whole of s.91 of the Constitution Act, 1867 is the residuary clause since the

federal government was granted the power to legislate "for the Peace, Order and good

Government of Canada, in relation to all Matters not coming within the classes of Subjects by

this Act assigned exclusively to the Legislature of the Provinces." (my emphasis) In other words,

the Provinces were given a list of specified fields of jurisdiction and the federal government was

given the rest. The list of powers (ss. 1-29) given in s. 91 was only an "illustrative list" of the

types of powers granted to the federal government and was included "for greater Certainty, but

not so as to restrict the generality of the foregoing Terms of this Section."

14

Gibbons v. Ogden, (1824) 9 Wh (195).

[ 11 ]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

On the face of it, there were then only two types of powers granted in the Constitution Act,

1867: 1) the specified list of the provincial governments; 2) the rest that went to the federal

government.

However, matters are not as simple as they first appear: the provincial list contained two clauses

which were not easily defined unless reference was made to the 29 categories of s. 91; these two

clauses were 92-13 ("Property and Civil Rights") and 92-16 ("Generally all Matters of a merely

local or private Nature in the Province"). Thus, instead of two, three compartments of powers

eventually appeared in the Constitution Act: 1) s.92; 2) the illustrative list of s .91 and 3) the

residuary clause which came into play only if powers could not be allocated through No. 1 or

No.2.

Thus, part of the residuary clause came to rest in s. 92-13 and in 92-16 since the definition of

Property and Civil Rights could only be gathered by removing from it the 29 classes found under

s.91; matters were to fall under the federal residuary clause if it was proven that the disputed

powers were undoubtedly of a general rather than a local nature and could not be linked to one

of the listed powers under s. 91 or s. 92.

Australia

When the six Australian colonies joined together in Federation in 1901, they became the original

States and ceded some of their powers to the new Commonwealth Parliament. Before

Federation, each colony had its own set of powers. At Federation some of these powers were

handed over to the Commonwealth (s 51). The remaining powers stayed with the states (s 108);

they are called the residual powers and only the states can make laws based on these powers.

Section 51 of the Constitution of Australia grants legislative powers to the Australian

(Commonwealth) Parliament only when subject to the constitution. There are 39 subsections to

section 51, each of which describes a "head of power" under which the Parliament has the power

to make laws.

The Commonwealth legislative power is limited to that granted in the Constitution. Powers not

included in section 51 are considered "residual powers", and remain the domain of the states,

unless there is another grant of constitutional power (e.g. Section 52 and Section 90 prescribe

[ 12 ]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

additional powers). Matters covered in section 51 may be legislated on by the states, but the

legislation will be ineffective if inconsistent with or in a field 'covered by' Commonwealth

legislation (by virtue of s109 inconsistency provision).

Switzerland

Switzerlands federal constitution, adopted in 1848 after a civil war, was a compromise that

sought to accommodate both the liberals (mainly Protestants) promoting a unitary state and the

conservatives (mainly Roman Catholics) defending the former Confederation. Based on a highly

decentralized federalism, the Cantons (the constituent units of the federation) maintained their

far-reaching original autonomy, now as self-rule within a federation, and continued to share their

sovereignty with the federation.

The constitutional concept of Switzerlands distribution of powers reflects a bottom-up

construction of the federation and depends, finally, on the residual powers of the Cantons and,

in some instances, even municipalities. As a logical consequence the Swiss Constitution does not

distribute the powers between the Confederation and the Cantons in a final list, and it does not

provide powers for the Cantons. In principle it determines exclusively the powers delegated to

the Confederation. Where new powers are delegated to the federal government, they are

formulated carefully so that, even within a delegated power, the Cantons still retain some part of

their sovereignty.

[ 13 ]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

CONCLUSION

Federalism leads to the setting up of a composite institution where there is a separate and

distinct union government, and state governments. The pattern of relationship is never rigidly

defined in the Indian Constitution. The fact that the relationship is based on an elastic set of

norms has always gone to the advantage of successive powerful union governments.

The concept of federalism in India is built upon the substructure of power sharing in a setup of

parliamentary democracy. In speaking about the concept of federalism-in-practice, we should be

sharply aware of the fact that from the moment the Constitution started to be drafted, the

concept of unity rather than diversity had a marked influence on the process of federalism. The

drive to create an indestructible union was also accompanied by the urge to foster and foist on

the nation, a driving supremacy of the Union over the State, in matters that concerned the

nations interests. Residuary Power of the Legislation is one such concept introduced in the

Indian Constitution by the framers of the Constitution who were able to perceive the future

legislative needs which would arise in future through there far sightedness has proved to be a

boon in keeping the federal character of our Constitution intact with a stronger Centre.

Unlike India, in the U.S.A. and in Australia, residuary powers are vested in the competent States,

while in Canada they belong to the Centre as the framers of the Canadian Constitution supposed

that the American system of vesting residuary powers in the state resulted in weakness of the

Federal Government and so they reversed the process, by leaving the residue to the Dominion

Parliament and conferring only those powers on the Provincial Legislatures which are required

for local purposes.

The comparison with other federal constitutions should provide some context to the residuary

powers clause in the Indian Constitution and help in better understanding it.

[ 14 ]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

N ATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, B HOPAL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Basu, D.D. Shorter Constitution of India, 11th edition. LexisNexis Butterworth.

Jain, M.P. Indian Constitutional Law. 7th ed. 2014.

Mehdi, Ali. Residuary Legislative Powers in India Retrospect & Prospects. Deep & Deep

Publications. 1990.

Rao, B. Shiva. The Framing of Indias Constitution, Vol. II.

Shukla, V.N. Constitution of India. Revised by Mahendra P. Singh; 10th Edition, Eastern

Book Company.

Websites

www.legalservicesindia.com

www.indiankanoon.com

[ 15 ]

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-III

RESIDUARY POWERS OF LEGISLATION

Você também pode gostar

- Residuary Power of The UnionDocumento12 páginasResiduary Power of The UnionDheeresh Kumar Dwivedi100% (2)

- Constitutional Law Project 3rd TriDocumento21 páginasConstitutional Law Project 3rd TriRadha CharpotaAinda não há avaliações

- IMPACT OF NATIONAL EMERGENCY ON FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IN INDIADocumento18 páginasIMPACT OF NATIONAL EMERGENCY ON FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IN INDIANarayanaAinda não há avaliações

- Parliamentary PrivilageDocumento34 páginasParliamentary PrivilageAmarendraKumarAinda não há avaliações

- Afspa: Legalising Violation of Human Rights?: Manvi Khanna & Nehal JainDocumento14 páginasAfspa: Legalising Violation of Human Rights?: Manvi Khanna & Nehal Jainvikas rajAinda não há avaliações

- Cooperative Federalism and Its Activity: Submitted By: Shubham Saini ROLL NO: R154216103Documento30 páginasCooperative Federalism and Its Activity: Submitted By: Shubham Saini ROLL NO: R154216103SHUBHAM SAINIAinda não há avaliações

- Constitution ProjectDocumento13 páginasConstitution ProjectMegha ChauhanAinda não há avaliações

- Maharashtra National Law University, Aurangabad: Constitutional Law II ProjectDocumento11 páginasMaharashtra National Law University, Aurangabad: Constitutional Law II ProjectSoumiki GhoshAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional LawDocumento17 páginasConstitutional LawShailesh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis of PHD in LAWDocumento49 páginasThesis of PHD in LAWKrishnaKousikiAinda não há avaliações

- Anubhav - 120 - Centre State RelationsDocumento12 páginasAnubhav - 120 - Centre State Relationshimanshu vermaAinda não há avaliações

- Judges Transfer CaseDocumento37 páginasJudges Transfer CaseSajal Singhai100% (1)

- Legislative Relations B/W Union & StateDocumento19 páginasLegislative Relations B/W Union & StateAnkush KhyoriaAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Federalism fINAL DRAFTDocumento9 páginasIndian Federalism fINAL DRAFTBharat JoshiAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Law Project On Death Penalty.Documento14 páginasConstitutional Law Project On Death Penalty.Shashank Shekhar Bhatt100% (2)

- Critical Evaluation of Preventive Detention Laws in IndiaDocumento18 páginasCritical Evaluation of Preventive Detention Laws in IndiaAshish Kumar LammataAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial Activism in IndiaDocumento10 páginasJudicial Activism in IndiaJAYA MISHRAAinda não há avaliações

- Relation Between Adminstrative Law and Constitutional LawDocumento18 páginasRelation Between Adminstrative Law and Constitutional LawRadha CharpotaAinda não há avaliações

- Right to Education in India: Provisions, Purpose and ProspectsDocumento17 páginasRight to Education in India: Provisions, Purpose and ProspectsGhanashyam RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of the Supreme Court judgement in Sarat Chandra Rabha v. Khagendra NathDocumento23 páginasAnalysis of the Supreme Court judgement in Sarat Chandra Rabha v. Khagendra NathNidhi PrakritiAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial IndependenceDocumento16 páginasJudicial IndependenceKunal SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Law ProjectDocumento18 páginasConstitutional Law Project17183 JOBANPREET SINGHAinda não há avaliações

- Capital PunishmentDocumento4 páginasCapital PunishmentMaheshkv MahiAinda não há avaliações

- Digital India and The Censor LawsDocumento18 páginasDigital India and The Censor LawsAayush TamrakarAinda não há avaliações

- Constitution Research Paper NewDocumento22 páginasConstitution Research Paper NewSARIKAAinda não há avaliações

- Women Equality and The Constitution of IndiaDocumento14 páginasWomen Equality and The Constitution of Indiarajendra kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison of Presidential and Parliamentary Forms of GovernmentDocumento22 páginasComparison of Presidential and Parliamentary Forms of GovernmentutkarshAinda não há avaliações

- Emergency Provisions in National Constitutions A ComparisonDocumento33 páginasEmergency Provisions in National Constitutions A ComparisonUriahAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Law 2 ProjectDocumento22 páginasConstitutional Law 2 ProjectRadheyAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Study of Judicial Pronouncements on Affirmative Action in India and the USDocumento14 páginasComparative Study of Judicial Pronouncements on Affirmative Action in India and the USanimes prustyAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Law ProjectDocumento11 páginasConstitutional Law ProjectAvinash UttamAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial Review of Preventive DetentionDocumento24 páginasJudicial Review of Preventive DetentionNiharika BhatiAinda não há avaliações

- Constitution's Preamble Role and AmendabilityDocumento3 páginasConstitution's Preamble Role and Amendabilityabhishek kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow: SynopsisDocumento3 páginasDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow: SynopsisHimanshi RaghuvanshiAinda não há avaliações

- Constitution Project FinalDocumento20 páginasConstitution Project FinalranzymanzyAinda não há avaliações

- Communal Violence and Counter Measures: A Juristic StudyDocumento23 páginasCommunal Violence and Counter Measures: A Juristic StudyRaju PatelAinda não há avaliações

- Constitution ProjectDocumento22 páginasConstitution ProjectDeepali SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Rule of Law and Separation of Powers: A Comparative StudyDocumento33 páginasRule of Law and Separation of Powers: A Comparative StudyShardul Vikram SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Reservatioin Policy in India and The Affirmative Actions in UsDocumento38 páginasReservatioin Policy in India and The Affirmative Actions in UssamAinda não há avaliações

- Relationship of Fundamental Rights and Human Rights.... Human RightsDocumento24 páginasRelationship of Fundamental Rights and Human Rights.... Human Rightsmohd suhail siddiquiAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Law (Federalism), Ishu Deshmukh, Semester-II, Roll No.-025Documento27 páginasConstitutional Law (Federalism), Ishu Deshmukh, Semester-II, Roll No.-025ishuAinda não há avaliações

- Affirmative Final Drfat MargaretDocumento14 páginasAffirmative Final Drfat MargaretMargaret RoseAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Law IDocumento17 páginasConstitutional Law Ilokesh chandra ranjanAinda não há avaliações

- National Law Institute University Bhopal: Subject: Affirmative Action Law Project On TopicDocumento19 páginasNational Law Institute University Bhopal: Subject: Affirmative Action Law Project On TopicKapil KaroliyaAinda não há avaliações

- Doctrine of Territorial Nexus in Indian LegislationDocumento16 páginasDoctrine of Territorial Nexus in Indian Legislationgaurav singh0% (2)

- Right To Food PDFDocumento77 páginasRight To Food PDFNishant AwasthiAinda não há avaliações

- Constitution Research PaperDocumento13 páginasConstitution Research PaperVivek GargAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Law FinalDocumento22 páginasConstitutional Law FinalNatasha SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Contempt of Court and Freedom of Speech A Dispute of Rights and Dignity Astha LaviDocumento11 páginasContempt of Court and Freedom of Speech A Dispute of Rights and Dignity Astha LaviLaw Colloquy100% (1)

- Right To Information As A Part of Freedom of Speech and Expression in India)Documento17 páginasRight To Information As A Part of Freedom of Speech and Expression in India)Razor RockAinda não há avaliações

- Sem. - X, Nishtha Shrivastava, Cr. L Socio Economic Offences Hons. I ProjectDocumento19 páginasSem. - X, Nishtha Shrivastava, Cr. L Socio Economic Offences Hons. I ProjectNISHTHA SHRIVASTAVAAinda não há avaliações

- India's Delegated LegislationDocumento14 páginasIndia's Delegated LegislationAkarsh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Ashok Kumar Thakur v. Union of IndiaDocumento10 páginasAshok Kumar Thakur v. Union of Indiashashank saurabhAinda não há avaliações

- Discover Fraud Types in Securities MarketsDocumento18 páginasDiscover Fraud Types in Securities MarketsUday ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial Review ComparisonDocumento20 páginasJudicial Review ComparisonVipin VermaAinda não há avaliações

- Consti 4th SemDocumento15 páginasConsti 4th SemDarpan MaganAinda não há avaliações

- Residuary Power of The UnionDocumento12 páginasResiduary Power of The Unionvijaya choudharyAinda não há avaliações

- Residuary Power of The UnionDocumento12 páginasResiduary Power of The UnionDeepak RavAinda não há avaliações

- Doctrine of Colourable LegislationDocumento15 páginasDoctrine of Colourable LegislationUditanshu MisraAinda não há avaliações

- Uttara Foods and Feeds Private Limited vs. Mona Pharmachem (13th Nov 2017)Documento3 páginasUttara Foods and Feeds Private Limited vs. Mona Pharmachem (13th Nov 2017)Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Lokhandwala Kataria Construction Pvt. Ltd. Vs Nisus Finance and Investment Manager, LLPDocumento3 páginasLokhandwala Kataria Construction Pvt. Ltd. Vs Nisus Finance and Investment Manager, LLPChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Key legal differences between past regime and IBCDocumento4 páginasKey legal differences between past regime and IBCChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Model Answer KeyDocumento5 páginasModel Answer KeyChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- IBC Cases SummaryDocumento7 páginasIBC Cases SummaryChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Prowess International Pvt. Ltd. vs. Parker Hannifin India Pvt. Ltd. (18th Aug 2017)Documento17 páginasProwess International Pvt. Ltd. vs. Parker Hannifin India Pvt. Ltd. (18th Aug 2017)Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Sterling Biotech Limited (5th Apr 2019)Documento8 páginasSterling Biotech Limited (5th Apr 2019)Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Swiss Ribons JudgementDocumento150 páginasSwiss Ribons JudgementVrind JainAinda não há avaliações

- Supreme Court Judgment on Time Limit for Curing Defects in Insolvency ApplicationDocumento32 páginasSupreme Court Judgment on Time Limit for Curing Defects in Insolvency ApplicationradhakrishnaAinda não há avaliações

- Prowess International Pvt. Ltd. vs. Parker Hannifin India Pvt. Ltd. (18th Aug 2017)Documento17 páginasProwess International Pvt. Ltd. vs. Parker Hannifin India Pvt. Ltd. (18th Aug 2017)Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Sanjeev Shriya vs. LML Ltd. & Ors. (20th Aug 2018)Documento2 páginasSanjeev Shriya vs. LML Ltd. & Ors. (20th Aug 2018)Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- InnoventiveDocumento88 páginasInnoventiveMandira PrakashAinda não há avaliações

- State Bank of India Vs V. Ramakrishna & Anr Civil Appeal No. 3595-2018Documento41 páginasState Bank of India Vs V. Ramakrishna & Anr Civil Appeal No. 3595-2018Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Bank recovery proceedings against guarantors can continue despite moratorium under IBCDocumento29 páginasBank recovery proceedings against guarantors can continue despite moratorium under IBCChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Moserbaer Writ Article 32 WP PDFDocumento53 páginasMoserbaer Writ Article 32 WP PDFVaibhav RatraAinda não há avaliações

- Supreme Court ruling on triggering insolvency for operational debtsDocumento92 páginasSupreme Court ruling on triggering insolvency for operational debtsSanket SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Refugee Laws and Judicial Decisions in IndiaDocumento37 páginasRefugee Laws and Judicial Decisions in IndiaChristina Shaju100% (1)

- 15th Dec 2017 in The Matter of Macquarie Bank Limited vs. Shilpi Cable Technologies Ltd. Civil Appeal No. 15135-2017 - 2017!12!19 10-25-23Documento74 páginas15th Dec 2017 in The Matter of Macquarie Bank Limited vs. Shilpi Cable Technologies Ltd. Civil Appeal No. 15135-2017 - 2017!12!19 10-25-23Praveen NairAinda não há avaliações

- Dr. V. Vijayakumar NLIU - B.A.LL.B (Hons) Electives - Refugee Law 2019Documento50 páginasDr. V. Vijayakumar NLIU - B.A.LL.B (Hons) Electives - Refugee Law 2019Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson-VII-RefugeeLawsinIndiaDocumento64 páginasLesson-VII-RefugeeLawsinIndiaChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- 2018 Judgement 02-Apr-2019 PDFDocumento84 páginas2018 Judgement 02-Apr-2019 PDFRaghav AgarwalAinda não há avaliações

- Arcelormittal India Private Limited Vs Satish Kumar Gupta & Ors. Civil Appeal Nos. 9402-9405 - 2018 PDFDocumento154 páginasArcelormittal India Private Limited Vs Satish Kumar Gupta & Ors. Civil Appeal Nos. 9402-9405 - 2018 PDFChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- UNHCR FactsheetSept2018Documento7 páginasUNHCR FactsheetSept2018Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- PART - VI - Durable SolutionsDocumento32 páginasPART - VI - Durable SolutionsChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Part-Ii-UnhcrDocumento17 páginasPart-Ii-UnhcrChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Part-IV-ASYLUMorREFUGEDocumento29 páginasPart-IV-ASYLUMorREFUGEChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- The Sources of International Law Relating To RefugeesDocumento18 páginasThe Sources of International Law Relating To RefugeesChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- (Constance Jordan, Karen Cunningham) The Law in Shakespeare (Early Modern Literature in History, 2007)Documento297 páginas(Constance Jordan, Karen Cunningham) The Law in Shakespeare (Early Modern Literature in History, 2007)Christina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Cultural PsychologyDocumento5 páginasCultural PsychologyYAMUNA BINDU 1833185Ainda não há avaliações

- Dylan and The Last Love Song of The American LeftDocumento9 páginasDylan and The Last Love Song of The American LeftChristina ShajuAinda não há avaliações

- Alfon Vs RepublicDocumento20 páginasAlfon Vs RepublicDenee Vem MatorresAinda não há avaliações

- Consti Digest 03.09.21Documento3 páginasConsti Digest 03.09.21Cecilia Alexandria GodoyAinda não há avaliações

- Ashley Withers ResumeDocumento1 páginaAshley Withers ResumeAshley Danielle DobsonAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Journalists, Inc. vs. Thoenen 477 Scra 482 (2005)Documento1 páginaPhilippine Journalists, Inc. vs. Thoenen 477 Scra 482 (2005)Syed Almendras IIAinda não há avaliações

- Mechanics of Corruption in Indian JudiciaryDocumento102 páginasMechanics of Corruption in Indian JudiciaryNagaraja Mysore Raghupathi100% (1)

- Legal EthicsDocumento222 páginasLegal EthicsJohn100% (1)

- Telmo V RepublicDocumento8 páginasTelmo V RepublicadeeAinda não há avaliações

- Enrollment ConformeDocumento1 páginaEnrollment ConformeIvan Gonzales100% (1)

- Kwin Transcripts - Consti - Until June 27 DiscussionDocumento112 páginasKwin Transcripts - Consti - Until June 27 DiscussionFerdinandopoeAinda não há avaliações

- Monitor Workplace Health and Safety with Regular InspectionsDocumento3 páginasMonitor Workplace Health and Safety with Regular InspectionsAan DaisyAinda não há avaliações

- Paderanga v. DrilonDocumento2 páginasPaderanga v. DrilonKrizzia GojarAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Procedure Exam NotesDocumento146 páginasCivil Procedure Exam Noteskazza91Ainda não há avaliações

- Supreme Court Rules on Qualified Theft CasesDocumento20 páginasSupreme Court Rules on Qualified Theft CasesAtty Richard TenorioAinda não há avaliações

- Investigation of house break-insDocumento4 páginasInvestigation of house break-insVenkanna UppulaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Ledesma Vs ClimacoDocumento11 páginas1 Ledesma Vs Climacojm bernalAinda não há avaliações

- Van Leeuwen v. Van Leeuwen, Ariz. Ct. App. (2014)Documento7 páginasVan Leeuwen v. Van Leeuwen, Ariz. Ct. App. (2014)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- RA 9344 As Amended by RA 10630 Juvenile JusticeDocumento63 páginasRA 9344 As Amended by RA 10630 Juvenile JusticeJoan Dymphna Saniel100% (4)

- Importance of Family Planning in IndonesiaDocumento2 páginasImportance of Family Planning in IndonesiaIchvan MeisyAinda não há avaliações

- Showlag V MansourDocumento14 páginasShowlag V MansourChelsea AzubuikeAinda não há avaliações

- Motion to Amend Charges in Frustrated Murder CaseDocumento3 páginasMotion to Amend Charges in Frustrated Murder CaseGenalyn Española Gantalao DuranoAinda não há avaliações

- PRIL Text Index PDFDocumento14 páginasPRIL Text Index PDFShavi Walters-SkeelAinda não há avaliações

- Dangerous Liaisons - Critical International Theory and ConstructivismDocumento37 páginasDangerous Liaisons - Critical International Theory and ConstructivismIan RonquilloAinda não há avaliações

- I-04 Cooperation AgreementDocumento9 páginasI-04 Cooperation AgreementGeorgio RomaniAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial Branch: Supreme Court of The United StatesDocumento12 páginasJudicial Branch: Supreme Court of The United StateslosangelesAinda não há avaliações

- Nrega FormatDocumento3 páginasNrega Formatrajt_26Ainda não há avaliações

- Moot Memorial R-33Documento21 páginasMoot Memorial R-33Karan singh RautelaAinda não há avaliações

- Abrams v. United States - 250 U.S. 616 PDFDocumento10 páginasAbrams v. United States - 250 U.S. 616 PDFBrigette MerzelAinda não há avaliações

- S V Dewani - S174 Application - Defence Heads of ArgumentDocumento127 páginasS V Dewani - S174 Application - Defence Heads of ArgumenteNCA.com75% (8)

- 10-05-18 Cal Law: Countrywide Staff Indicted On Mortgage FraudDocumento2 páginas10-05-18 Cal Law: Countrywide Staff Indicted On Mortgage FraudHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)Ainda não há avaliações

- Reference - Adequacy Audit ChecklistDocumento7 páginasReference - Adequacy Audit Checklistnoor prayoga mokogintaAinda não há avaliações