Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Evaluacion de Screening para Disfagia en Niños

Enviado por

Sebastián Andrés ContrerasTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Evaluacion de Screening para Disfagia en Niños

Enviado por

Sebastián Andrés ContrerasDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Brain & Development 37 (2015) 508514

www.elsevier.com/locate/braindev

Original article

Assessment of feeding and swallowing in children: Validity

and reliability of the Ability for Basic Feeding and Swallowing

Scale for Children (ABFS-C)

Anri Kamide a,, Keiji Hashimoto a, Kohei Miyamura b, Manami Honda a

a

Division of Rehabilitation Medicine and Developmental Evaluation Center, National Center for Child Health and Development, Japan

b

Tokyo Metropolitan Ohtsuka Hospital, Japan

Received 21 April 2014; received in revised form 14 August 2014; accepted 18 August 2014

Abstract

Objective: The purpose was to devise a dysphagia scale for disabled children that could be applied by various medical professionals, family members, and personnel in treatment and education institutions and facilities for disabled children and to assess the

validity and reliability of that scale, Ability for Basic Feeding and Swallowing Scale for Children (ABFS-C). Methods: Subjects

were 54 children (aged 2 months to 14 years and 7 months, median 14 months) who visited the National Center for Child Health and

Development from January 2012 to December 2013. They were examined using the Fujishimas Grade of Feeding and Swallowing

Ability (Fujishimas Grade), the Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM) and the ABFS-C composed of 5 items

(wakefulness, head control, hypersensitivity, oral motor and saliva control). Validity was evaluated according to correlations of the

ABFS-C with Fujishimas Grade or WeeFIM. To assess interrater reliability, 17 children were assessed by a doctor and occupational

therapist independently. Results: The ABFS-C scores and Fujishimas Grade were correlated using Spearman rank correlation coefcients. Fujishimas Grade was signicantly correlated with saliva control (R = 0.470) and the total ABFS-C scores (R = 0.322) but

not with wakefulness (R = 0.014), head control (R = 0.122), hypersensitivity (R = 0.009), or oral motor (R = 0.139). In addition,

the total ABFS-C scores had a signicant correlation with the total score of the WeeFIM (R = 0.562), motor WeeFIM (R = 0.451),

cognitive WeeFIM (R = 0,478), and the eating subscore of the WeeFIM (R = 0.460). Interrater reliability was demonstrated for all

items except hypersensitivity. Conclusions: There were signicant correlations between the total ABFS-C scores and Fujishimas

Grade and WeeFIM, which suggested the need for comprehensive assessments rather than assessments of individual feeding and

swallowing functions. To improve the reliability for hypersensitivity, the assessment process for hypersensitivity should be reviewed.

2014 The Japanese Society of Child Neurology. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Dysphagia; Children; ABFS-C; Clinical assessment scale

1. Introduction

Dysphagia rehabilitation in our country involves

multiple professions engaged in the treatment of primar-

ily physically disabled children with cerebral palsy or

neuromuscular disease. Recently, however, a wider

range of conditions such as developmental disorders

and tube-feeding dependency have to be addressed

Corresponding author. Address: National Center for Child Health and Development, 10-1, Okura 2-chome, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 157-8535,

Japan. Fax: +81 (3) 3416 2222, +81 (3) 3416 0181.

E-mail address: kamide-a@ncchd.go.jp (A. Kamide).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2014.08.005

0387-7604/ 2014 The Japanese Society of Child Neurology. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

A. Kamide et al. / Brain & Development 37 (2015) 508514

[1,2]. Childrens feeding and swallowing function is

developed not only through functional and morphological growth of oropharyngeal organs but also through

the development of other organs and psychophysiological functions. Consequently, children with dysphagia

can be pathogenetically classied into those aected by

retardation of functional development and those

aected by a reduction of acquired function. Features

of disability are thus so complicated that multiple assessments not only limited to the disease have to be

performed.

Neither here nor abroad, no satisfactory assessment

scale for childhood dysphagia has been established that

applies a clinical assessment based on an interview and

observation with an auxiliary diagnosis using imaging

methods [3]. Items found in textbooks for clinical assessment are wide-ranging, specialized, and timeconsuming. It is, therefore, desirable to develop an

assessment scale that would allow those with diverse

roles, varying from family members to personnel in

medical treatment institutions and welfare facilities such

as those facilities serving disabled children to arrive at a

shared understanding of dysphagia in disabled children.

We developed a feeding and swallowing function version of the Ability for Basic Movement Scale for

Children (ABMS-C) [4], which we had developed to

briey assess the ability for movement in children. In

addition, we veried the validity and reliability of the

new instrument.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Subjects

From January 2012 to December 2013, 54 pediatric

patients with dysphagia at the National Center for Child

Health and Development newly received rehabilitation.

There were 24 males and 30 females, and their median

age was 14 months (aged 2 months to 14 years and

7 months). They were classied according to the primary

pathogenesis as follows: organic, 17 (4, malignant disease; 3, laryngeal paralysis; 3, laryngomalacia; 2, cheilognathopalatoschisis; 2, gastroesophageal reux; 1, cleft

tongue; 1, multiple malformation; 1, esophageal atresia);

neurological, 28 (6, chromosome or genetic abnormality; 3, cerebral palsy; 3, hydrocephalus; 3, history of living donor liver transplantation; 3, extremely low birth

weight; 2, brain tumor; 2, epilepsy; 2, multiple malformation; 1, cerebrovascular disease; 1, encephalitis; 1,

hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; 1, history of cardiac

surgery); psychobehavioral, 5 (2, anorexia; 2, developmental disorder; 1 tube-feeding dependency after

operations); and developmental, 4 (3, tube-feeding

dependency due to inammatory bowel disease; 1,

history of cardiac surgery). They were classied

by swallowing phases as follows: postural control

509

preparation phase, 6; oral preparatory phase, 10; oral

phase, 4; pharyngeal phase, 32; and esophageal phase, 2.

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the National Center for Child Health and

Development. Informed consent was obtained from

family members of all of the children.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Ability for Basic Feeding and Swallowing Scale

(ABFS-C)

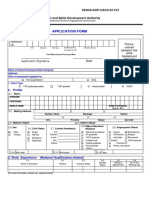

The ABFS-C is composed of 5 items pertaining to a

childs feeding and swallowing ability, i.e. wakefulness,

head control, hypersensitivity, oral motor ability, and

saliva control. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale

from 0 to 3. Fig. 1 shows assessment contents of the

ABFS-C.

Wakefulness is an index of food recognizability

reecting the patients general status prior to a feeding

and swallowing act. It is rated according to the Glasgow

Coma Scale as 0 in the case of failure to respond to pain

stimulation, as 1 if the patient is awakened by swaying

of the body, as 2 if the patient is awakened by speech,

or as 3 if the patient is awake without any stimulation.

Head control provides information on the patients

development of motor activity in the feeding posture or

the severity of neurological symptoms. As in the case of

the Ability for Basic Movement Scale for Children, [4]

head control is graded as 0 if the neck is completely

unstable, as 1 if the neck follows when both shoulders

are raised to 45 degrees, as 2 if the neck follows but stays

xed for less than 10 s when both shoulders are raised to

90 degrees, and as 3 if the neck is perfectly stable.

Hypersensitivity is a type of pediatric-specic

dysesthesia and is an index of the degree of lack of experience with feeding and swallowing. The patient is examined for such dysesthesia by slow movement of the

examiners palm while touching the patients body surface in the order of the upper and lower limbs from

the periphery to the center, the face, and around the lips

and oral cavity. Observation of changes in the patients

facial expression determines whether or not hypersensitivity is present. It is graded as 0 if hypersensitivity is

present all over the body, as 1 if it is present around

the lips, as 2 if it is present in the oral cavity, and as 3

if there is no hypersensitivity.

Oral motor ability serves as an index of the developmental degree of tongue and lip motor function and

the severity of neurological symptoms. Around the time

that a child acquires food-holding ability, he/she can

open or close the lips. Later, the child can move the tongue back and forth or up and down, and then from side

to side. Subsequently, the child becomes able to voluntarily protrude the tongue beyond the lips. Consequently, 0 represents the inability to close the lips or

move the tongue, 1 indicates lack of ability to move

510

A. Kamide et al. / Brain & Development 37 (2015) 508514

score

no response

wakefulness

to pain

no head control

head control

whole body

hypersensitivity

hypersensitive

to touch

oral motor

wakes up

when shaken

stimulus

or move tongue

can hold head up in line with can hold head up but not for

body when both

10 sec when

shoulders are

both shoulders

raised 45

are raised

degrees

90 degrees

does not like objects

does not like objects

touching lips

touching inside

or mouth area

the mouth

but cannot move

tongue

saliva control

constantly drooling

awake

when called to

can move lips

cannot close lips

wakes up

constant throat

can hold head up for

10 sec when both

shoulders are raised

90 degrees

not hypersensitive

can close lips

can close lips

and can move

and can stick

tongue inside

tongue outside

the mouth only

the mouth

throat gurgling

no throat gurgling

after stimulation

after stimulation

inside the mouth

inside the mouth

gurgling

Fig. 1. ABFS-C: Ability for Basic Feeding and Swallowing Scale for Children.

the tongue but the ability to close the lips, 2 denotes that

tongue movement is limited to the inside of the oral cavity, and 3 signies voluntary movement of the tongue

beyond the lips.

Saliva control is a risk index for aspiration that is

surmised from saliva control and the amount of food residue in the pharynx. It is graded as 0 if the child is always

unable to swallow saliva, resulting in overow of saliva

that has pooled in the oral cavity from the lips; as 1 if

pharyngeal secretions always make a gurgling sound,

as 2 if pharyngeal secretions make a gurgling sound only

after oral stimulation (stimulation is selected from gum

rubbing, gustatory stimuli, presentation of usual food,

etc. depending on the childs condition), and as 3 if there

are no gurgling sounds of pooled pharyngeal secretions

after oral stimulation.

2.2.2. Validity

To explore the validity of the ABFS-C, we assessed

the patients feeding and swallowing ability, and which

was scored according to the Fujishimas Grade of Feeding and Swallowing Ability (Fujishimas Grade) [5] and

the Food Intake LEVEL Scale (FILS) [6]. These scales

measure the severity of dysphagia by examining to what

degree patients take food orally. They are primarily

applied to adults and are used all over Japan. As these

instruments did not include factors related to childhood

growth and development, we modied them so that they

described how the child took food in a form that corresponded to that by a normally developed child of the

patients age.

Fujishimas Grade determines the severity of a swallowing disorder as necessary by using a videouoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) or a beroptic endoscopic

evaluation of swallowing (FEES). Severity is rated as

follows: Grade 1, diculty in swallowing or inability

to swallow, no indication for swallow training; Grade

2, indication only for basic swallow training; Grade 3,

aspiration occurs less often when conditions are right,

swallow training is feasible; Grade 4, feeding can be

enjoyable; Grade 5, oral intake is partially possible (1

or 2 meals); Grade 6, oral intake of 3 meals is possible

but alternative nutritional therapy is required; Grade

7, oral intake of easy-to-swallow food is possible at 3

meals; Grade 8, oral intake is possible at 3 meals unless

food is particularly hard to swallow; Grade 9, oral

intake of regular meals is possible under clinical watch

and guidance; and Grade 10, normal feeding and swallowing ability.

FILS determines the severity of dysphagia by judgment based on food forms and ratios of oral intakes

on a daily basis. Ratings are as follows: Level 1, no swallowing training is performed except for oral care; Level

2, swallowing training not using food is performed;

Level 3, swallowing training using a small quantity of

food is performed; Level 4, easy-to-swallow food less

than the quantity of a meal is ingested orally; Level 5,

easy-to-swallow food is orally ingested in one to two

meals, but alternative nutrition (non-oral nutrition such

as tube feeding and drip infusion) is also given; Level 6,

the patient is supported primarily by ingestion of easyto-swallow food in three meals, but alternative nutrition

is used as a complement; Level 7, easy-to-swallow food

is orally ingested in three meals and no alternative nutrition is given; Level 8, the patient eats three meals by

excluding food that is particularly dicult to swallow;

Level 9, there is no dietary restriction, and the patient

ingests three meals orally, but medical considerations

A. Kamide et al. / Brain & Development 37 (2015) 508514

are given; and Level 10, there is no dietary restriction,

and the patient ingests three meals orally (normal). In

the above assessment, we had the patient ingest regular

food consumed by normally developed children of the

same age (i.e. milk for a 3-mon-old baby, soft solid food

for an 8-mon-old baby).

In addition, we assessed the patients disability status

using the Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM). It is an 18-item, 7-level ordinal scale

instrument that measures a childs consistent performance of essential daily functional skills. The 18 items

are organized into 6 subscales of self-care (including eating), sphincter control, transfers, locomotion, communication, and social cognition. Total score of the motor

WeeFIM consists of scores for the subscales of self-care,

sphincter control, transfers, and locomotion. Total

scores of the cognitive WeeFIM consist of scores for

the subscales of communication and social cognition.

The Spearman rank method was employed to explore

correlations between items on the ABFS-C or total

scores of the ABFS-C and Fujishimas Grade or the

FILS in 54 pediatric patients. We similarly examined

the strength of the association between items on the

ABFS-C or total scores of the ABFS-C and the total

scores of WeeFIM, motor WeeFIM, and cognitive

WeeFIM and the eating subscore in the motor WeeFIM

in 31 children (12 boys, 19 girls; aged 2 months to

7 years and 8 months, median 11 months). Statistical

software used was SPSS Statistics 20.

2.2.3. Interrater reliability

Interrater reliability was evaluated employing examination of 17 of the above-mentioned children (8 boys, 9

girls; aged 3 months to 38 months, median 7 months).

Assessment was made separately by a doctor and an

occupational therapist using the ABFS-C at the rst

examination to seek weighted k coecients of resultant

data on individual items using the above-mentioned

software. Assessment dates diered at most by 1 week

511

between the doctor and occupational therapist involved

in the assessment. They were kept unaware of their

counterparts assessment scores during the study period.

2.2.4. Internal consistency

Internal consistency of the 5 items comprising the

ABFS-C was checked by Cronbachs coecient alpha

(Cronbachs A) in 54 pediatric patients.

3. Results

3.1. Validity

Whereas there was a signicant correlation between

Fujishimas Grade and saliva control (R = 0.470) or

the total score of the ABFS-C (R = 0.322), no obvious

correlation was found between Fujishimas Grade and

wakefulness (R = 0.014), head control (R = 0.122),

hypersensitivity

(R = 0.009)

or

oral

motor

(R = 0.134). Additionally, FILS had no signicant correlation with total scores or each item of the ABFS-C

(Table 1).

Results of the correlation coecient analysis that

compared scores of the ABFS-C and WeeFIM are

shown in Table 2. The total score of the ABFS-C

signicantly correlated with the total score of the WeeFIM (R = 0.562), motor WeeFIM (R = 0.451), cognitive WeeFIM (R = 0.478), and the eating subscore of

WeeFIM (R = 0.460). In addition, the total score of

the WeeFIM had a signicant correlation with head

control (R = 0.423) and oral motor (R = 0.440), and

the eating subscore of WeeFIM had a signicant correlation with oral motor (R = 0.373).

3.2. Interrater reliability

Scores on wakefulness and head control indicated

almost perfect interrater reliability (weighted k = 1.0,

weighted k = 0.889) while oral motor and saliva control

Table 1

Correlations of total scores of the ABFS-C with Fujishimas Grade or with FILS.

N = 54

Wakefulness

Head control

Hypersensitivity

Oral motor

Saliva control

Total score of ABFS-C

Grade

Level

Grade

Median

Range

3.00

3.00

3.00

0.00

2.00

11.00

4.00

5.00

03

03

03

03

03

015

110

110

ABFS-C: Ability for Basic Feeding and Swallowing Scale for Children.

Fujishimas Grade: Fujishimas Grade of Feeding and Swallowing Ability.

FILS: Food Intake LEVEL Scale.

*

p < 0.05.

**

p < 0.01.

Level

p

0.014

0.122

0.009

0.134

0.470**

0.322*

0.918

0.378

0.951

0.335

0.000

0.018

0.803**

0.000

p

0.225

0.001

0.086

0.043

0.331*

0.098

0.803**

0.102

0.992

0.535

0.760

0.014

0.480

0.000

512

A. Kamide et al. / Brain & Development 37 (2015) 508514

Table 2

Correlations of total scores of the ABFS-C with WeeFIM.

N = 31

Wakefulness

Head control

Hypersensitivity

Oral motor

Saliva control

Total score of

ABFS-C

Wee FIM

Total score

Motor WeeFIM

r

Median

Range

3.00

3.00

3.00

2.00

2.00

11.00

03

03

03

03

03

015

0.106

0.423*

0.071

0.440*

0.222

0.562**

0.570

0.018

0.705

0.013

0.231

0.001

0.089

0.354

0.004

0.359*

0.281

0.451*

Cognitive WeeFIM

Eating subscore of motor

WeeFIM

0.635

0.051

0.984

0.047

0.125

0.011

0.098

0.389*

0.029

0.375*

0.147

0.478**

0.601

0.031

0.878

0.038

0.429

0.007

p

0.089

0.354

0.009

0.373*

0.288

0.460**

0.634

0.051

0.964

0.039

0.116

0.009

ABFS-C: Ability for Basic Feeding and Swallowing Scale for Children.

WeeFIM: Functional Independence Measure for Children.

*

p < 0.05.

**

p < 0.01.

Table 3

Inter-rater reliability of each ABFS-C item by doctor and occupational

therapist (OT).

N = 17

Wakefulness

Head control

Hypersensitivity

Oral motor

Saliva control

*

**

Doctor

OT

Doctor

OT

Doctor

OT

Doctor

OT

Doctor

OT

Reliability

Median

Range

Weighted j

3.00

3.00

3.00

3.00

3.00

0.00

3.00

3.00

1.00

1.00

03

03

03

03

03

03

03

03

03

03

1.0*

0.000

0.889**

0.000

0.016

0.879

0.500*

0.006

0.502*

0.001

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

had moderate correlations (weighted k = 0.500,

weighted k = 0.502). On the other hand, hypersensitivity

showed no signicant interrater reliability (weighted

k = 0.016) (Table 3).

3.3. Internal consistency

The 5 items on the ABFS-C had appropriate internal

consistency (Cronbachs A = 0.974).

4. Discussion

The prevalence of childhood dysphagia is estimated

to fall between 25% and 45% in typically developing

children and between 33% and 80% of children with

developmental disability, [7] with an upward trend

currently in place. There are more than a few very

complicated and diversied structural, neurological

and psychobehavioral abnormalities that occur in the

process of growth and development [8]. Moreover, close

collaboration is required among disciplines to manage

disabled children since a variety of professions as well

as facilities become engaged in their management in

accordance with changes that take place from infancy/

childhood to school age/adulthood [1,2]. Consequently,

an assessment scale is desired that can easily identify the

whole picture of dysphagia in a child so that information can be shared among disciplines. At present,

however, in our country, individual facilities or communities assess dysphagia in their own distinctive ways.

Decision tables for dysphagia rehabilitation levels

and aspiration risks, which are being used in some pediatric rehabilitation centers, are the easiest to use but

they have not been satisfactorily veried for reliability

and validity [9]. An assessment approach proposed by

Murayama et al. [10] was aimed at detecting aspiration

in children with cerebral palsy and is therefore inappropriate for assessment of children with other disabilities.

A number of assessment methods for children have been

reported abroad [3,1115]. A systematic review of 27

papers published before 2012 [16] cited the Schedule

for Oral Motor Assessment (SOMA) [17] as an excellent

assessment method with regard to reliability, validity,

and clinical usefulness. This method was aimed at

assessing oral motor function and distinguishes between

normal and abnormal function by determining whether

feeding status for each of 5 food forms exceeded the

minimum level. However, it is not commonly used in

actual examinations because it is suitable only for dysphasic children with issues of the oral phase. Thus, the

reality is that there is no assessment method that is standardized for comprehensive assessment and severity

classication with substantiation of reliability and validity [11].

We therefore developed the ABFS-C to provide a

simple scale that could easily assess pediatric dysphagia

in daily life. One of the most useful points of the

A. Kamide et al. / Brain & Development 37 (2015) 508514

ABFS-C in comparison with other scales is that we can

easily record comprehensive ability regardless of dierent phases of feeding and swallowing, and then can

monitor the progress of the childs ability without a

VFSS or FEES.

Our results showed that total scores of the ABFS-C

had a signicant correlation with Fujishimas Grade,

total scores of the WeeFIM, motor WeeFIM, cognitive

WeeFIM, and the eating subscore of the WeeFIM. The

5 items on the ABFS-C had also appropriate internal

consistency. On the other hand, regarding items on the

ABFS-C, saliva control had a signicant correlation with

Fujishimas Grade but wakefulness, head control, hypersensitivity, and oral motor did not. In addition, there

were signicant correlations between total scores of the

WeeFIM and head control and oral motor. Oral motor

had the only signicant correlation with the eating subscore of the WeeFIM. Consequently, it was suggested

that severity assessment required a more comprehensive

assessment including not only individual swallowing

functions but also consciousness levels, sensation disorders and gross motor functions. FILS had no signicant

correlation with total scores of the ABFS-C or each of its

items except saliva control. This dierence from our ndings with Fujishimas Grade was because Fujishimas

Grade indicated how much the patient can do based

on a VFSS or FEES whereas FILS reected the patients

actual feeding action according to the direction by

their primary doctor [18]. Therefore, FILS was not

always determined with food forms suitable to the

patients feeding and swallowing ability probably resulting in a discrepancy between those levels and ABFS-C

scores. Moreover, since subjects diered in the causes

of dysphagia, including causative diseases and disorders

of the swallowing stages, it was suggested that the ABFSC had the potential to be used to assess disabled children

in general. Based on these results, we believe that the

ABFS-C is an eective assessment scale that reects the

severity of pediatric dysphagia.

Interrater reliability of the ABFS-C was veried in 4

items: wakefulness, head control, oral motor and saliva

control. On the other hand, such reliability was not

demonstrated in hypersensitivity, which may have been

because we do not have a good scale for evaluating

hypersensitivity in the body, lips and oral cavity. An

examiner whom the patient doesnt know has diculty

distinguishing between hypersensitivity and psychological refusal, so there might have been dierences in rating

between examiners. Since a past unpleasant experience,

a fear of strangers, or emotional insecurity due to a long

hospitalization may cause psychological refusal, it

seemed necessary to revise results of the assessment after

hearing about the patients responses when touched by a

family member. In addition, since dierent sensory stimuli other than touching with the examiners ngers,

including touching with a pacier, toothbrush or cup,

513

taste stimulus and thermal stimulus, may elicit dierent

responses, examiners might have faced diculty in decision making. We thought that there was yet room for

improvement in the assessment procedure, including

unication of kinds of sensory stimuli.

Finally, several limitations of this study should be

mentioned. First, it remains necessary to explore the

clinical utility of each item of the ABFS-C. We would

like to use the SOMA for validation in pediatric patients

with oral phase problems, and explore whether or not

scores are properly allocated to each item and whether

or not developing processes are reected in each age category using other international development evaluation

scales such as the Ages & Stages Questionnaires (ASQ)

or the Kinder Infant Development Scale (KIDs).

Second, we have to revise the assessment procedure

for hypersensitivity and its wording. Finally, it is necessary to evaluate interrater reliability between professionals and non-professionals. Then, we plan to accumulate

further cases and further revise this assessment tool.

References

[1] Mukai Y. History of developmental studies on eating function [in

Japanese]. Dental Med Res 2013;33:2334.

[2] Nagai S, Koike J. Rehabilitation for pediatric dysphagia. Sogo

Rehabil 2011;39:2317 [in Japanese].

[3] Arvedson JC, Brodsky L. Pediatric swallowing and feeding:

assessment and management. 2nd ed. New York: Singular Pub

Group Press; 2002.

[4] Miyamura K, Hashimoto K, Honda M. Validity and reliability

of Ability for Basic Movement Scale for Children (ABMS-C)

in disabled pediatric patients. Brain Dev 2011;33:

50811.

[5] Fujishima I. Rehabilitation for swallowing disorders associated

with stroke [in Japanese]. 2nd ed. Tokyo: Ishiyaku Publishers

Inc.; 1998.

[6] Kunieda K, Ohno T, Fujishima I, Hojo K, Morita T. Reliability

and validity of a tool to measure the severity of dysphagia: the

Food Intake LEVEL Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage

2013;46:2016.

[7] Lefton-Greif MA. Pediatric Dysphagia. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N

Am 2008;19:83751.

[8] Groher ME, Crary MA. Dysphagia: clinical management in

adults and children. 1st ed. St. Louis: Mosby Inc; 2009.

[9] Yokoyama M. Risk of rehabilitation in patients with profound

intellectual and multiple disease. Sogo Rehabil 2012;40:13742 [in

Japanese].

[10] Murayama K, Kanda T, Kondo I, Kitazumi E, Kodama K.

Assessment of dysphagia in the patient with cerebral palsy a

chart to estimate the possibility of aspiration in patients with

severe motor and intellectual disabilities. Jpn J Dysphagia

Rehabil 2004;8:14355 [in Japanese].

[11] Nishio M. Recent international trends in rehabilitation of

pediatric dysphagia. Jpn J Dysphagia Rehabil 2008;12:119 [in

Japanese].

[12] Stratton M. Behavioral assessment scale of oral functions in

feeding. Am J Occup Ther 1981;35:71921.

[13] Ottenbacher K, Dauck BS, Gevelinger M, Grahn V, Hassett C.

Reliability of the behavioral assessment scale of oral functions in

feeding. Am J Occup Ther 1985;39:43640.

[14] Cintas HL, Parks R, Don S, Gerber L. Brief assessment of

motor function: content validity and reliability of the upper

514

A. Kamide et al. / Brain & Development 37 (2015) 508514

extremity gross motor scale. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr

2011;31:44050.

[15] Sheppard JJ. Using motor learning approaches for treating

swallowing and feeding disorders: a review. Lang Speech Hear

Serv Sch 2008;39:22736.

[16] Benfer KA, Weir KA, Boyd RN. Clinimetrics of measures of

oropharyngeal dysphagia for preschool children with cerebral

palsy and neurodevelopmental disabilities: a systematic review.

Dev MedChild Neurol 2012;54:78495.

[17] Ko MJ, Kang MJ, Ko KJ, Ki YO, Chang HJ, Kwon JY. Clinical

usefullness of schedule for oral-motor assessment (SOMA) in

children with dysphagia. Ann Rehabil Med 2011;35:47784.

[18] Fujishima I, Oono T, Takahashi H, Katagiri H, Kuroda Y,

Ishibashi A, et al. Development of the scale of feeding and

swallowing: the Food Intake Level Scale. Jpn J Rehabil Med

2006;43:S249 [in Japanese].

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Cdev 2 Child and Adolescent Development 2Nd Edition Spencer A Rathus Full ChapterDocumento51 páginasCdev 2 Child and Adolescent Development 2Nd Edition Spencer A Rathus Full Chapterdarrell.pace172100% (18)

- Learning For Success (LFS) : Sajeevta FoundationDocumento5 páginasLearning For Success (LFS) : Sajeevta FoundationGautam Patel100% (1)

- Assignment Stuff AssignmentsDocumento11 páginasAssignment Stuff Assignmentsapi-302207997Ainda não há avaliações

- 002LLI Castillo LTDocumento6 páginas002LLI Castillo LTJohnny AbadAinda não há avaliações

- English: Quarter 4 - Module 4: Reading Graphs, Tables, and PictographsDocumento23 páginasEnglish: Quarter 4 - Module 4: Reading Graphs, Tables, and PictographsResica BugaoisanAinda não há avaliações

- Lab 3Documento3 páginasLab 3bc040400330737Ainda não há avaliações

- CE Section - Docx 1.docx EDIT - Docx ReqDocumento7 páginasCE Section - Docx 1.docx EDIT - Docx ReqEdzel RenomeronAinda não há avaliações

- Advice To Young SurgeonsDocumento3 páginasAdvice To Young SurgeonsDorelly MartinezAinda não há avaliações

- Neha Ajay UpshyamDocumento2 páginasNeha Ajay UpshyamSantoshKumarAinda não há avaliações

- Cover LetterDocumento1 páginaCover Letterapi-282527049Ainda não há avaliações

- Shade T' If The Statement Is True and Shade F' If The Statement Is False in The True/false Answer Sheet ProvidedDocumento6 páginasShade T' If The Statement Is True and Shade F' If The Statement Is False in The True/false Answer Sheet ProvidedMUHAMMAD IKMAL HAKIM ABDULLAH100% (1)

- A General Inductive Approach For Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation DataDocumento11 páginasA General Inductive Approach For Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation DataThủy NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Biodentine: The Dentine in A Capsule or More?Documento12 páginasBiodentine: The Dentine in A Capsule or More?Razvan DumbraveanuAinda não há avaliações

- Explicit TeachingDocumento8 páginasExplicit TeachingCrisanta Dicman UedaAinda não há avaliações

- Research Process: Presented By:-Aditi GargDocumento12 páginasResearch Process: Presented By:-Aditi Gargpllau33Ainda não há avaliações

- National Strength and Conditioning Association.1Documento19 páginasNational Strength and Conditioning Association.1Joewin EdbergAinda não há avaliações

- 3 - U2L1-The Subject and Content of Art-AAPDocumento5 páginas3 - U2L1-The Subject and Content of Art-AAPFemme ClassicsAinda não há avaliações

- Form Ac17-0108 (Application Form) NewformDocumento2 páginasForm Ac17-0108 (Application Form) NewformEthel FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- 54819adb0cf22525dcb6270c PDFDocumento12 páginas54819adb0cf22525dcb6270c PDFEmaa AmooraAinda não há avaliações

- Key Data Extraction and Emotion Analysis of Digital Shopping Based On BERTDocumento14 páginasKey Data Extraction and Emotion Analysis of Digital Shopping Based On BERTsaRIKAAinda não há avaliações

- Ogl 320 FinalDocumento4 páginasOgl 320 Finalapi-239499123Ainda não há avaliações

- Analytical Solution For A Double Pipe Heat Exchanger With Non Adiabatic Condition at The Outer Surface 1987 International Communications in Heat and MDocumento8 páginasAnalytical Solution For A Double Pipe Heat Exchanger With Non Adiabatic Condition at The Outer Surface 1987 International Communications in Heat and MDirkMyburghAinda não há avaliações

- Differentiated LearningDocumento27 páginasDifferentiated LearningAndi Haslinda Andi SikandarAinda não há avaliações

- The Fourteen Domains of Literacy in The Philippines MTB-MLE CurriculumDocumento32 páginasThe Fourteen Domains of Literacy in The Philippines MTB-MLE CurriculumKaren Bisaya100% (1)

- Topic 9 Remedial and EnrichmentDocumento13 páginasTopic 9 Remedial and Enrichmentkorankiran50% (2)

- 7 Habits in Short 1Documento30 páginas7 Habits in Short 1api-3725164Ainda não há avaliações

- Report DPDocumento4 páginasReport DPHeryien SalimAinda não há avaliações

- Modified Lesson PlanDocumento6 páginasModified Lesson Planapi-377051886Ainda não há avaliações

- Life Skills Lesson 7 Respect Others LessonDocumento4 páginasLife Skills Lesson 7 Respect Others LessonAnonymous QmyCp9Ainda não há avaliações

- MTM Proposal Template (WordDocumento6 páginasMTM Proposal Template (Wordccp16Ainda não há avaliações