Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?

Enviado por

jaykhan85Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?

Enviado por

jaykhan85Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Vol. 0, No. 0, xxxxxxxx 2016, pp.

113

ISSN 1059-1478|EISSN 1937-5956|16|00|0001

DOI 10.1111/poms.12549

2016 Production and Operations Management Society

What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The

Retailing Functions?

Jia Li

Krannert School of Management, Purdue University, 403 West State Street, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA, jial@purdue.edu

Tat Y. Chan

Olin Business School, Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1133, St. Louis, Missouri 63130-4899, USA,

chan@wustl.edu

Michael Lewis

Goizueta Business School, Emory University, 1300 Clifton Road, Atlanta, Georgia 30322, USA, mike.lewis@emory.edu

his study examines the effects of a relatively new channel structure on prices and sales in a large department store,

which in recent years has switched the management of many of its product categories from a traditional retailer-managed system to a manufacturer-managed system. We find that the change caused overall retail prices to decrease. However, there was significant heterogeneity in the response across brands. In the cell phone category, brands with high

market shares and inelastic demand did not change prices. In the watch category, the retail prices of relatively low-end

brands decreased while the prices of premium brands increased substantially after the switch. In addition to sales

increases due to lower prices, we find that the channel structure change further caused sales to increase by 910% in the

cell phone category and by 1117% in the watch category. These results are consistent with previous theoretical predictions. We believe that our results provide important academic and managerial implications due to the increasing prevalence of manufacturer-managed systems in the retail industry.

Key words: retailing; channel management; decision delegation; empirical study; marketing

History: Received: January 2015; Accepted: December 2015 by Amiya Chakravarty, after three revisions.

1. Introduction

In a traditional retail channel structure, a retailer

typically sells multiple differentiated products produced by multiple manufacturers. Manufacturers

determine wholesale prices and the retailer selects

order quantities, sets retail prices, conducts in-store

promotions and manages the sales staff. We refer to

this traditional structure as a retailer-managed retail

(RMR) system because the retailer determines and

manages the marketing environment faced by consumers. This structure may be advantageous

because retailers typically have better information

about consumer demand in the local market and

possess core competencies in retailing activities such

as merchandising and promotion planning. In addition, previous research (Coughlan 1985, McGuire

and Staelin 1983) has found that using a retailer as

an intermediary may reduce competition between

manufacturers and may thereby be preferable for

manufacturers whose products are highly substitutable. However, RMR suffers from well-known

channel coordination issues such as double-margin-

alization (Spengler 1950) and information distortion

(Lee et al. 1997). These coordination challenges

make it difficult for manufacturers and retailers to

resolve their conflicting interests and maximize the

total channel profit (Cachon 2003).

Recently, manufacturer-managed retailing (MMR)

systems have become increasingly popular. For example, in all major U.S. department stores, categories

such as jewelry, cosmetics, and apparel have been

managed under MMR. In contrast to RMR, in a MMR

system manufacturers set up selling counters and hire

their own sales staff to sell their products inside a

retail store. In return, the retailer is paid a percentage

of the total sales revenue generated in the store. MMR

has gained popularity because it has the potential to

reduce channel conflicts and can thereby benefit both

retailers and manufacturers. First, because manufacturers sell their own products and decide their own

retail prices under MMR, the double-marginalization

problem is eliminated. Second, MMR systems may

also reduce the frequency of stock-outs and the bullwhip effect for manufacturers with high demand

variability.

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

However, MMR may have its own potential issues.

On one hand, if negotiations between retailers and

manufacturers result in retailers claiming excessively

high shares of sales revenues, manufacturers may

have to set prices above the level that optimizes total

channel profits. On the other hand, in MMR the direct

competition between manufacturers within a store

can potentially result in more intensive price competition that leads to lower retail prices. Because of these

two conflicting forces, it is not entirely clear if retail

prices will be lower under MMR. In addition, revenue-sharing between the retailer and manufacturers

may lead to distortions in non-price promotional and

selling efforts from both parties. For example, since

the retailer does not retain all sales revenues it is

likely to have less incentive to push in-store promotions. Thus, it is also not clear if MMR will generate

higher retail sales than RMR. Better understanding

the consequences of RMR and MMR requires empirical investigation, which is the purpose of the current

study.

Our study utilizes data from a Chinese department

store that shifted from RMR to MMR in many product

categories. Although confined to a single retailer, this

type of quasi-experiment enables us to conduct direct

tests of the impact of the channel structure change.

This before-and-after analysis provides significant

advantages relative to a cross-sectional study. In this

study, we focus on two categories: cell phones1 and

watches. The nature of the shifts from MMR to RMR

differed across these two categories. In the cell phone

category all brands were first sold under RMR and

then were simultaneously switched to MMR. This

one-time policy change enables a clean comparison of

the whole category under the two channel structures.

In contrast, in the watch category, brands were

switched one by one from RMR to MMR over time. In

addition to the two focal categories, we also obtained

data from the same time period for another two product categories sold in the same department store,

and data from another department store located in

the same area that did not change channel structure

during the sample period. This enables us to use

controls to rule out alternative explanations that the

observed impacts of the channel structure change

were due to demand or cost shocks at the market or

store level.

Our results show that after switching to MMR the

average retail prices across all brands decrease in both

the cell phone category and the watch category by

10.7% and 3.34.3%, respectively. The magnitude of

the price decrease reflects the intensified price competition among manufacturers under MMR. The price

decreases drive higher sales. After controlling for

price effects, we find an additional 910% sales

increase in the cell phone category, and an 1117%

sales increase in the watch category. Although we

cannot identify from the data the exact factors that

drive the additional sales increase, the store management indicated that manufacturers increased the size

of sales staffs and offered a higher commission. We

further explored how the effects of switching to MMR

differ across brands using a latent class regression

approach. Results show that in the cell phone category the effects are the strongest for brands with

small market shares and for those with more elastic

demand. In the watch category, relatively low-end

brands cut prices while premium brands increase

prices after the channel structure change. Both types

of brands still experience sales growth. The increase

in prices of the high-end brands is a surprising result

since competition generally increases in a MMR

system.

2. Literature Review

Our research contributes to the operations and marketing literature on channel management. The current

literature does not provide adequate analysis of the

increasingly popular phenomenon in practice, that is,

MMR. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

empirical study to directly test the consequences of

MMR systems.

Our research is closely related to the vertical relationship and channel coordination literatures. As previously mentioned, a widely recognized channel

coordination issue is the double-marginalization

problem, that is, retailers charge higher retail prices

than the optimal level which maximizes total channel

profits (Shepard 1993, Spengler 1950). Numerous theoretical studies have focused on how to use various

transfer pricing schemes or other formal agreements

to improve channel coordination (e.g., see Cachon

2003, Cachon and Lariviere 2005). Policies such as

implicit understanding (Shugan 1985), formation of

conjectures (Jeuland and Shugan 1988) and category

captainship (Kurtulus et al. 2014, Subramanian et al.

2010) have also been studied. However, those models

are seldom empirically tested in the marketplace due

to the lack of data. Moreover, the majority of studies

in this literature focuses on the case of a monopoly

manufacturer.

In reality, retailers such as the department store in

our data, typically sell multiple differentiated products. McGuire and Staelin (1983) show that in a market with duopoly manufacturers, vertical integration

is a stable equilibrium channel structure when interbrand substitutability is low, though it does not necessarily maximize the total profit for the channel. When

products are highly substitutable, however, independent retailers provide a buffer that reduces the price

competition between manufacturers. Coughlan (1985)

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

generates similar conclusions for a wide set of

demand functions. Moorthy (1987) derives some general conditions under which this type of decentralized

channel structure is a Nash equilibrium. Choi (1991)

studies a similar case with two competing manufacturers selling substitutable products through a common independent retailer. Rey and Stiglitz (1995)

propose that in markets with imperfect competition,

vertical restraints such as exclusive territories can be

used to reduce the degree of inter-brand competition.

On the other hand, a single manufacturer may sell its

product through not only independent retailers but

also its own stores, leading to a dual channel structure. Consequently, competition can arise between

the independent retailer and the manufacturer-owned

store, a phenomenon often referred to as supplier

encroachment (Arya et al. 2007, Li et al. 2014, Wang

et al. 2009). Arya et al. (2007) show that while introducing competition between the supplier and the

retailer, supplier encroachment can mitigate double

marginalization and thus benefit both sides, if the

retailer is more efficient in the retail process. Our

study provides a comparison between the outcomes

when manufacturers sell through a retailer (RMR)

and when they directly integrate with the retail

activities and compete on the same retail floor

(MMR). These empirical results are complementary to

the above theoretical literature.

This study also complements the growing body of

empirical research on channel management. Some

researchers have identified and quantified the vertical

relationship between retailers and manufacturers.

Kadiyali et al. (2000), for example, measure the power

of channel members by looking at how channel profits are divided. They find that greater channel power

results in greater share of the total channel profit.

Sudhir (2001) studies competition among manufacturers under alternative assumptions of vertical interactions with one retailer. Villas-Boas (2007) extends the

work by allowing for multiple retailers. These studies

focus on the more traditional channel structure, that

is, RMR. In addition, they use cross-market or crossstore data and rely on structural assumptions of vertical strategic interactions between manufacturers and

retailers. The current study provides empirical testing

of the economic consequences of two channel systems

using a quasi-experiment within a retail store.

Previous empirical research has also examined various methods such as information sharing, synchronized replenishment and collaborative product

design that could facilitate the coordination between

manufacturers and retailers. Clark and Hammond

(1997) study the use of continuous replenishment programs (CRP) in the grocery products supply chain.

They find that implementing CRP improves the channel performance to a substantially greater degree than

using electronic data interchange (EDI) alone. Lee

et al. (1999) examine the CRP used by Campbells and

its retailers and document performance improvements in terms of inventory efficiency and stock-out

reduction.

Vendor-managed inventory (VMI) is a popular system for facilitating channel coordination. In a VMI

system, retailers provide manufacturers with access

to their real-time inventory levels and let them decide

inventory replenishments (Aviv and Federgruen

2003, Mishra and Raghunathan 2004). Cachon and

Fisher (1997) identify the benefits of VMI for Campbells but argue that these benefits are achieved

through information sharing. Dong et al. (2014), however, show that the transfer of inventory decision

making from the retailer to the manufacturer under

VMI also significantly improves channel performance. Direct-Store-Delivery (DSD) is another

method to facilitate channel coordination, where

upstream manufacturers are responsible for delivering product to retail stores, managing store shelf

space and inventory, and planning and executing instore merchandising (Kurtulus and Savaskan 2013).

Chen et al. (2008) empirically examine the economic

efficiency of DSD systems using cross-market data.

MMR is similar to VMI and DSD in the sense that

manufacturers also have autonomy in controlling

inventory and product delivery. Under MMR, however, the retailer also delegates many other decisions,

including pricing and sales staff management, to

manufacturers. This leads to many economic consequences that have not been explored in the empirical

literature. For example, since manufacturers also set

retail prices and manage product selling within

stores, competition in pricing and service provision

may be intensified. In recent work, Jerath and Zhang

(2010) use a theoretical model to study the storewithin-a-store phenomenon, which essentially is the

same as MMR. They show that the increased competition drives down retail prices but manufacturers

enjoy higher profits. Consequently, manufacturers

have a greater incentive to invest in providing better

customer services. Our study provides empirical tests

for their analytical results. Furthermore, their model

assumes that retailers charge manufacturers an

up-front fixed rent, which is different from a MMR

system under which retailers charge manufacturers a

percentage of sales revenue. We also investigate the

possibility of heterogeneous responses to MMR across

manufacturer brands, and find several interesting

results that are not predicted by Jerath and Zhang

(2010). In another related study, Abhishek et al.

(2015) theoretically examine the price implications

when an online retailer changes from the traditional

reselling arrangement (i.e., RMR) to agency

selling (similar to MMR) in a multi-channel retailing

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

exit. Many new brands were only available in the

store for 1 or 2 years before pulling out, or being

replaced by the store with a new brand. In the empirical analysis, we focused on brands with a consistent

presence for the entire 4 year period. We further

excluded from the analysis two brands that merged in

the third year. We also followed a suggestion from

the store management to drop another brand that dramatically altered its brand position and marketing

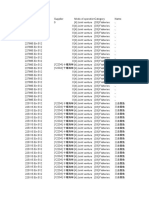

strategy. Table 1 provides some summary statistics of

the remaining 10 brands.

Overall, the 10 brands dominated category sales

throughout the sample period with an average total

market share of 82%. We compared the pricing and

sales trends for the 10 brands with the overall category and did not find any significant difference.

Hence, we believe that the exclusion of other brands

should not have a major impact on the empirical

results. Prior to the switch to MMR, prices and sales

of the cell phone category in the store had been

declining over time. This was consistent with the

managements observation that the store was facing

more and more competition from the new emerging

cell phone specialty stores in the market. Table 1

shows that there are two clear segments among the 10

brands brands 14 have much larger market shares

(based on quantity sales) and annual sales revenues

than brands 510. Prices are also quite different as the

average price of brand 4 is the highest at US$297.28,

while brand 6 is the lowest at $142.59. However, since

there is a large within-brand price variation across

models (comparing the minimum and the maximum

prices in Table 1) depending on the functionality,

attributes, and model introduction date, there is no

obvious segmentation between brands based on

price.

For the watch category, there are 14 brands in our

data. We excluded one that only had a short presence

in the store. Table 2 presents summary statistics for

the remaining 13 brands. Over the sample period

environment (online and offline) in which sales in one

channel may have an impact on sales in another channel. Due to data limitations our study only focuses on

a single channel.

3. Data and Channel Structure Changes

Our data is sourced from one of the largest department stores in China. We collected information on

transaction-level sales, prices and promotional discounts for a period of four calendar years. In addition,

we also obtained data on store advertising and counter locations of each brand inside the store. In interviews, the store management expressed their view

that, like other big retailers in China, the department

store had significant channel power as manufacturers

need the store to reach consumers in the local market

(manufacturer-owned stores were not as common as

in the United States.).

The retailer initially used traditional RMR but since

1990s has gradually switched its categories to MMR.

The management stated that historically categories

with low profits to the store were believed to be prime

candidates for MMR. The major reasons were that,

firstly, they believed there was a strong incentive for

manufacturers with poor sales to improve service and

hence sales. Secondly, MMR helps improve the financial liquidity of the store. Under RMR the store has to

pay manufacturers up-front for shipments. The managers also emphasized that they had the bargaining

power to make these manufacturers agree to the new

contracts lest they would not sell in the store. During

our data collection window about 90% of products

were managed under MMR.

In this study, we focus on the cell phone and watch

categories. The number of cell phone brands varied

from 56 to 65 in our data. During this period, government policy was to allow easy access to the telecommunications market. As a result, competition within

the industry was intense with significant entry and

Table 1 Cell Phone Category Summary Statistics

Annual market share

(%)

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Annual sales revenue

(US$1000)

Weekly retail price

(US$)

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Average

weekly

feature ad.

19.46

17.90

12.83

12.03

6.18

4.58

4.21

2.13

1.40

1.88

15.72

11.92

8.26

9.87

3.17

1.03

1.88

1.29

0.75

0.56

25.99

25.82

22.77

16.37

8.42

6.49

5.95

4.64

2.60

2.49

3980

3292

1207

2724

636

464

789

380

329

258

3367

2959

992

2519

625

407

759

347

297

217

4394

3712

1539

2995

654

494

824

413

356

297

199.51

216.67

174.75

297.28

153.83

142.59

293.58

196.42

191.36

147.90

128.64

148.02

112.30

222.10

105.93

73.46

100.49

124.32

104.94

91.85

437.90

339.88

253.28

402.84

216.71

208.40

594.81

246.67

320.12

207.28

0.19

0.19

0.29

0.15

0.27

0.25

0.14

0.15

0.21

0.13

Average

no. of

models

49

55

33

15

15

13

21

12

19

22

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

Table 2 Watch Category Summary Statistics

Annual market share

(%)

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

Brand

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Annual sales revenue

(US$)

Weekly retail price

(US$)

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Average

weekly

feature ad.

1.01

1.29

2.46

8.02

10.22

2.71

2.10

10.17

13.73

11.05

15.48

7.26

16.94

0.45

0.33

1.07

6.69

7.66

1.19

1.29

8.50

10.52

9.15

9.71

1.54

13.56

2.07

1.92

4.64

10.28

11.02

4.44

3.23

11.56

18.83

12.63

19.21

11.62

24.66

141,048

103,767

73,235

33,439

21,354

14,948

10,266

11,139

11,501

7591

5440

2965

2724

76,809

68,916

56,963

30,735

17,376

11,891

3853

10,237

10,063

6527

2511

1232

1938

30,3613

132,301

110,476

35,839

26,607

16,798

13,305

12,392

13,232

9222

7653

3984

4770

6632.75

2399.07

1988.06

736.65

514.72

376.07

290.33

278.52

277.32

171.17

95.31

89.31

55.64

2603.25

1301.63

1126.41

400.50

255.32

190.24

127.66

154.19

85.11

125.78

37.30

40.55

20.38

22,528.16

10,438.05

3379.22

1752.07

833.46

650.81

600.75

455.78

429.90

570.71

312.89

261.58

140.39

0.008

0.005

0.013

0.069

0.074

0.060

0.074

0.078

0.129

0.083

0.092

0.069

0.079

average retail prices increased as the result of increasing commodity prices. However, this price change

did not result in a decrease in sales. Similar to the cell

phone category, there is also significant heterogeneity

across brands. Average prices in the category range

from US$56 for brand 13 to $6633 for brand 1. The difference is so substantial that brand 1 generates the largest annual sales revenue even though its market

share in terms of quantity sales is only 1%. In contrast,

brand 13 has the largest quantity sales but its annual

revenue is the smallest in the store.

As noted, a key feature of the data is a switch from

RMR where the store determined retail prices, managed the inventory, and hired and managed sales

staff. Following the change to MMR all of these

responsibilities were shifted to individual manufacturers. For the cell phone category, the switch was

abrupt and applied to the whole category at the same

time. Prior to April of the fourth year all brands were

under RMR. At the end of February in that year, the

store made the decision to switch to MMR. Negotiation of revenue sharing contracts with individual

manufacturers began in March and the first brand

started switching to MMR in the middle of April. By

the end of April, all brands had switched to the new

retailing system.

In contrast, the switch to MMR in the watch category was a gradual process. Six major brands operated using MMR at the beginning of the data

collection period. One brand (brand 12) switched

from RMR to MMR in September of the first year. This

was followed by changes for brands 7 and 5. In

September of the third year, brand 1, the most expensive brand, was switched to MMR. The store then

switched brand 4, another high-end brand, in April of

year 4. At the end of the fourth year (the end of our

data collection period), only brands 2 and 3 were still

operated as retailer-managed brands.

Average

no. of

models

83

130

118

116

96

156

102

139

77

105

54

82

55

The store management stated that no major events

such as sudden changes in production and selling

costs, or entry and exit among manufacturers, had

driven the shift toward MMR. Rather, the adoption of

MMR was viewed as a method for dealing with the

long term trend of growing competition that was

common to all department stores in the market. In

particular, discount and specialty stores had been

emerging as important competitors for many categories including cell phones and watches. The general

view of the retailer is that MMR is a means for reducing competitive pressures and for shifting risk to

manufacturers. Such rationale is consistent with the

arguments made by Jerath and Zhang (2010). We

therefore make an important identification assumption in our empirical tests. That is, after controlling for

observed factors in data, the channel structure

changes are independent from unobserved demand

shocks in the market or cost shocks experienced by

manufacturers. To check the validity of this assumption and rule out potential endogeneity concerns, we

collected two additional types of data from the same

time period. The first was data from another two categories of products sold by the focal store on the same

floor next to either the cell phone counters or the

watch counters. The second was data from the watch

category from another department store located in the

same city that did not experience a policy change during the sample period. Details are provided in the

next section.

4. Empirical Tests: Overall Changes in

Prices and Sales

In this section, we develop hypotheses regarding how

the change in channel structure will impact key managerial metrics. We then discuss our modeling

approach and present our estimation results for the

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

two categories in our data. Finally, we discuss how

we use additional data as controls and also use a

short time window before and after the change to rule

out alternative explanations of our results.

4.1 Research Hypotheses

Jerath and Zhang (2010) offer testable hypotheses on

how switching from RMR to MMR may impact retail

prices and sales. They use an analytical model to

show that the increased manufacturer competition

drives down retail prices. Based on their results we

propose Hypothesis 1:2

HYPOTHESIS 1. Retail prices will decrease when a brand

is shifted from RMR to MMR. These price decreases will

result in increased sales.

Jerath and Zhang (2010) also consider how nonprice factors such as the in-store service level will be

different under the alternative systems. They argue

that because manufacturers make a higher profit margin under MMR, there is a greater incentive for them

to provide service to consumers. In our empirical context, other non-price factors such as counter design,

brand advertising and product assortment may also

influence demand. These increases in selling efforts in

a MMR system may lead to increased store traffic and

hence higher sales. In addition to the selling effort,

direct management of inventory by manufacturers

may also reduce stock-outs (Cachon 2003). Based on

this discussion we propose Hypothesis 2:

HYPOTHESIS 2. In addition to the effect of price decreases

on sales there will be a net increase in retail sales when a

brand is shifted from RMR to MMR.

4.2 The Effects of the Channel Structure Change

on Retail Prices

We first test the effects of the channel structure

change on the overall retail price by estimating a price

regression model. For brand i in week t, we specify

pit di Z0it q hsit tit ;

where pit is the log of the average retail price

weighted by aggregate sales of each SKU in the total

sample period of brand i in week t. The variable sit

is a binary variable that indicates whether the brand

is retailer-managed (sit = 0) or manufacturer-managed (sit = 1). The coefficient di is a brand fixed effect

used to account for the differences in quality and

production costs across brands. We use a vector of

observables, Zit, to control for new model introductions and time trends. New models are defined as

those products whose first sale is observed in the

preceding 30 days. We use two specifications to

control for time effects. The first specification

includes yearly (Year 2 to Year 4) and monthly

(February to December) indicators (Model 1) while

the second one uses the number of weeks since the

start of the sample period (Model 2) as a covariate.

A comparison of these specifications provides a test

of the robustness of our regression results. Finally it

is an error term.

Key results for the cell phone category are reported

at columns 1 and 2 of Table 3. The negative coefficients for the time variables reflect the fact that prices

of cell phones in the department store are decreasing

in general due to outside competitions. The estimated

coefficient for sit in both specifications implies that

retail prices drop by 10.7% on average after the channel structure change. Given that the average retail

price for all brands in our sample is roughly US$200,

this is a significant change as manufacturers markups

in this category may be as low as $10 under RMR.

Key results for the watch category are reported at

columns 3 and 4 of Table 3. Coefficients for the yearly

dummies or the weekly time trend are significantly

positive. The estimated coefficient for sit varies from

%0.03 to %0.04, depending on the model specification.

Since the average retail price of the watch category is

around US$1000, this represents a price decrease of

$30 to $40. Overall, the results of both categories are

consistent with Hypothesis 1 that MMR intensifies

price competitions among manufacturers.

4.3 The Effects of the Channel Structure Change

on Retail Sales

We next evaluate the effects of the channel structure

change on sales. In particular, we are interested in

sales growth that is not explained by the downward

movement of prices. We first study the cell phone category by estimating a (log) sales regression model.

For brand i in week t,

qit bi Xit0 v c1i pit c2 cpit dsit nit ;

where qit is the log of quantity sales of brand i in

week t, and the parameter bi represents the brand

Table 3 Estimation Results of Price Change due to the Channel

Structure Change

Cell phone category

Parameters

Channel

structure change

Year 2

Year 3

Year 4

Weekly

time trend

Model 1

Model 2

%0.107***

%0.107***

%0.019***

%0.126***

%0.186***

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

%0.001*

Watch category

Model 1

%0.043*

0.171***

0.341***

0.515***

N/A

Model 2

%0.033**

N/A

N/A

N/A

0.003***

*, **, ***significant at 0.10, 0.05, 0.01 level.

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

fixed effect on sales. The channel structure switch

indicator sit is the same as in the price regression

model. We also include brand is own price, pit, and

a competitive price term, cpit. The latter is represented by the average retail price of other brands in

the same week, weighted by the aggregate sales of

each brand throughout the sample period. Xit is a

vector of observed factors that may affect retail sales

including the following: (1) time effects again we

use two specifications, yearly (Year 2 to Year 4) and

monthly (February to December) indicators, and the

number of weeks since the start of the sample period; (2) the stores feature advertising, which is a

dummy variable, equal to 1 if any product under is

brand name is featured in the stores weekly ad of

week t, and 0 otherwise; (3) the number of new

models of brand i in week t; and (4) two location

indicators. Selling counters for cell phones were

relocated twice during the sample period. The first

relocation occurred in the third year when the store

decided to renovate the floor where selling counters

were located and the second location change

occurred in the fourth year.

The parameter c2 in the equation denotes the crossprice elasticity, which for simplicity is assumed to be

the same across brands. The parameter c1i is a brandspecific own-price elasticity. The indirect effect of the

channel structure change on retail sales due to price

changes is equal to c1i for each brand multiplied by h

in Equation (1). In addition to this indirect effect, d in

Equation (2) captures the net gain of retail sales due

to the channel structure change. Finally, it is an error

term representing unobserved demand shocks.

Next we consider the watch category. The sparseness of sales in the category means we do not observe

brand sales in some weeks of data. When sales occur,

we also need to account for the discreteness of the

quantity sold in our model. To account for these data

issues, we assume that observed sales are generated

from a negative binomial distribution function. The

expected quantity sold is specified as

Eqit j Xit ; pit ; cpit ; sit '

bi Xit0 v c1i pit c2 cpit dsit nit ;

where all parameters and variables are defined in

the same way as in Equation (2), with the only difference being that there is no relocation of the watch

category in our data.

Key results of the sales regression for both of the

categories are reported in Table 4. Coefficients for the

time variables (yearly dummies or weekly time

trends) are significantly negative for the cell phone

category, reflecting the fact that the department store

is facing increased competition from discount and

specialty stores. Coefficients for the two relocation

Table 4 Estimation Results of Sales Change due to the Channel

Structure Change

Cell phone category

Watch category

Parameters

Model 1

Model 2

Model 1

Model 2

Channel

structure change

Log(Own Price)

Brand 1

Brand 2

Brand 3

Brand 4

Brand 5

Brand 6

Brand 7

Brand 8

Brand 9

Brand 10

Brand 11

Brand 12

Brand 13

Log(Cross Price)

Advertising

New Models

Relocation 1

Relocation 2

Year 2

Year 3

Year 4

Weekly

Time Trend

0.102***

0.085**

0.111***

0.171***

%0.075***

%0.095***

%0.168*

%0.246***

%0.232**

%0.263**

%0.277***

%0.477***

%0.401**

%0.631***

%0.681***

%0.545***

%0.954***

0.071**

0.206***

N/A

N/A

N/A

0.076

%0.042

0.158

N/A

%0.185***

%0.112***

%0.277*

%0.382***

%0.390***

%0.331***

%0.469***

%0.507***

%0.544***

%0.829***

%0.953***

%0.816***

%1.450***

0.087***

0.223***

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

%0.001

%0.564***

%1.091***

%1.458***

%0.641***

%1.693***

%1.648***

%1.240***

%1.399***

%1.560***

%2.150***

N/A

N/A

N/A

0.227*

0.148***

0.022***

0.097***

%0.191***

%0.074***

%0.143***

%0.233***

N/A

%0.520***

%1.181***

%1.413***

%0.672***

%1.671***

%1.703***

%1.264***

%1.340***

%1.576***

%2.256***

N/A

N/A

N/A

0.04

0.157***

0.029***

0.074***

%0.225***

N/A

N/A

N/A

%0.001***

*, **, ***significant at 0.10, 0.05, 0.01 level.

indicators for the cell phone category are significant,

showing the impact of moving counters on sales. For

both categories own-price coefficients are all significantly negative while cross-price coefficients are significantly positive (with the exception of the cell

phone category in Model 2). These estimates are consistent with our expectations. In the cell phone category, demand for brands 1 and 4 is significantly less

elastic to price changes than demand for other brands.

In the watch category, own-price coefficients are closely related to price and sales. The least price-elastic

brands (13) consist of premium brands with the

highest prices and largest sales revenues, while the

most price-elastic brands (1013) are low-end brands

with lower annual sales revenues.

For the cell phone category, the coefficient for the

channel structure change implies that the shift to MMR

directly caused retail sales to increase by an additional

910% above the effects due to lower prices. For the

watch category, we also find significant gains in sales

as the coefficient is 0.11 in Model 1 and 0.17 in Model

2. These results support Hypothesis 2. There are various reasons that may explain this net sales increase.

First, under RMR sales representatives were store

employees, while after the change they worked

directly for manufacturers. Sales representatives from

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

manufacturers may have better product knowledge

since they specialize in selling products for a single

brand. By focusing on selling their own brands, manufacturers may benefit from greater salesperson specialization. We were also told by the store management

that the number of sales representatives increased by

about 10% following the shift to MMR and that

employees were also offered a higher commission from

manufacturers. These changes suggest that manufacturers invested more in service provision, consistent

with the findings in Jerath and Zhang (2010).

Advertising is another important factor that may

affect sales. The net sales gain might also be explained

if the store increased its feature advertising for the

category after the channel structure change. Since we

have included feature advertising in the sales regression, increased advertising should not be the primary

reason. Manufacturers might also have increased

their own advertising spending in the local market.

Given that the shift to MMR occurred in a single store,

we do not believe that this was the case. Another possibility is that other non-price factors (e.g., counter

design and selling space) inside the store were

improved. However, we do not have data to test this

explanation. Another possible reason for the sales

increase is that the shift to MMR led to stock-out

reductions. Mishra and Raghunathan (2004), for

example, show that manufacturers have an incentive

to keep a higher stock of their own brand under VMI.

In addition, Mahajan and van Ryzin (2001) show that

when firms are providing substitutable goods, there

is a bias toward overstocking caused by the competition. As a proxy for stock-outs, we checked the ratio

of the number of days with zero levels of inventory to

the total number of days when the category was

under RMR. For the cell phone category the ratio varies from 1% (brand 1) to 5.5% (brand 8), indicating

that stock-outs might have significantly lowered store

sales. There is no evidence of stock-outs in the watch

category. We do not have access to inventory data

after the channel structure was shifted to MMR hence

we are unable to make direct comparisons.

Finally, there may be changes in the product offerings after the switch. For example, manufacturers

might offer greater variety when they directly manage

their own counters. It is also possible that after the

channel structure change, manufacturers put their

newest models on the counter shelf. To evaluate these

possibilities we examined the total number of cell

phone models sold in store for the 2 months before

and after the switch but did not find significant differences in the total number of models sold in the store.

However, 7 out of 10 brands did sell more new models after the channel structure change. For the watch

category the number of SKUs of each brand is very

stable over the entire sample period.

4.4 Robustness Checks and Alternative

Explanations

The above results are consistent with our hypotheses

1 and 2. In this section, we conduct further robustness

checks of our results. In addition, we also provide further evidence to rule out some alternative explanations to our empirical results.

4.4.1. Robustness to Model Specifications. We

estimated two types of GLS price regressions as a

robustness check of our main model on prices. The

first one allows for a potential correlation of the error

terms in the price regression across brands and the

second one allows for a potential correlation of the

error terms across weeks under the AR(1) assumption. We also repeat the same procedure for the sales

regression model. All of the results are similar to what

we report in Tables 3 and 4, showing that our results

are robust to model specifications.

In addition to the actual prices paid by consumers

we also observe listed prices in the data. Listed prices

may be different from the final retail prices for two

reasons. First, occasional price promotions occur

under both RMR and MMR. Second, salespeople have

the authority to offer small discounts to certain customers. For manufacturers, occasional price promotions or offering reduced prices to specific customers

may help to avoid a full-scale price war with competitors. We ran another set of price regressions using the

log of listed prices as the dependent variable in the

regression. Again we find that most of the results are

similar to those in the preceding analysis. However,

we also find that the probability of price discounts

(i.e., final retail prices are lower than list prices) is, in

general, higher after the channel structure change. On

average, the promotion frequency in the cell phone

category increased from 36.6% to 70.7%. In the watch

category, the brands that experienced a shift to MMR

also tended to increase promotional activity (Brand 1

is an exception).

4.4.2. Demand and Cost Shocks. There are some

potential alternative explanations to our price and

sales results. One alternative explanation is that our

findings and the switch to MMR are both caused by

demand or cost shocks in the local market. Although

the management stated that this was not the reason

for switching to MMR, we consider it important to

rule out such alternative explanations from the data.

To achieve this purpose we collected data on prices

and retail sales for the watch category from another

department store located in the same city.3 This store

is independent from our focal store and targets similar customers in the market. Its annual sales revenue

is about one-fourth that of our focal retailer, but is still

ranked among the top 100 department stores in the

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

we did using the data from the control store. The idea

is that if a shock occurred within the store, it would

impact all categories on the same retail floor in the

same way. The results are reported in Panel (2) and

Panel (3) of Table 5, respectively. None of the results

is significant, and three out of the four coefficients for

the sales regression are negative.4

country. In the watch category, this store has 11 major

brands, 8 of which are also available in our focal store.

The entire watch category was under MMR during

the sample period hence there was no change in the

control store. To evaluate the possibility of unobserved demand shocks we created an artificial channel structure switch dummy for the periods during

which a shift occurred in our focal store, and ran the

price and sales regressions using data from the control store. If channel structure switches were driven

by demand or cost shocks at the market level, significant changes would also be observed at the control

store during those periods.

Key results are presented in Table 5, Panel (1). In

the price regression, the coefficient for the artificial

channel structure switch is negative using yearly and

monthly dummies (1(a)) but positive using a weekly

time trend (1(b)). Neither is statistically significant. If

there were a market-level cost shock or demand shock

that caused the price drops in the watch category in

the focal department store, we would observe the

same result in the other store. The coefficients in the

sales regression under both time specifications are

also insignificant. Furthermore, while the effect of the

channel structure switch on sales is positive in our

analysis, the coefficients for the artificial dummy are

negative in the control store. These results help rule

out the explanation that the observed price and sales

changes of the watch category in the focal store are

due to cost or demand shocks in the local market.

It is also possible that there were demand or cost

shocks that affected only the focal store, and those

shocks were concurrent with the switch to MMR. As

we discussed previously, however, the store management stated that no such shocks existed. To further

rule out this explanation, we collected additional data

on other categories sold by the store. We chose the

clothing category that was sold on the same floor as

the cell phone counters, and the gold and jewelry category that was located on the same floor as the watch

counters. We then re-ran the price and sales regressions with an artificial channel structure switch

dummy for the two new categories, similar to what

4.4.3. Competitive Environment. Another potential explanation for our results is that the price and

sales changes were driven by changes in the competitive environment inside and outside the department

store over time. For example if there were more

entrant brands than exit brands in the store we might

expect a more intensive within-store competition in

the later part of our sample period. This type of effect

could also produce a negative coefficient for the channel structure change parameter in the price regression. In the data there were 62 brands in the cell

phone category before the switch, and only five small

brands (average annual market share of the largest of

these brands is 0.8%, and the total market share of the

five brands is 2.4%) left after the switch. It is unlikely

that these five small brands would have significant

impact on the intensity of competition in the category.

Furthermore a reduction in the total number of

brands should mitigate rather than increase competitive pressures. For the watch category, the total number of brands was stable before and after the switches

so again it does not explain the observed price

changes.

Competition outside the store that is not captured

by the time variables in the regressions may be

another factor. A decrease in competition might

explain why the coefficient for the channel structure

change is positive in our sales regressions. We explore

this possibility by selecting data from 1 month before

and 1 month after the changes to MMR in the cell

phone and watch categories to run the price and sales

regressions again. This practice is similar to the regression-discontinuity approach in the literature.

The logic is that while outside competition may have

changed over time, if the change was continuous and

Table 5 Main Results of Price and Sales Regressions for Control Store and Categories

(1)

Regression

Control

variables

Artificial switch

dummy

(2)

(3)

Log (Price)

Sales

Yearly and monthly

dummies

Log (Price)

Sales

Weekly time

trend

Log (Price)

Sales

Yearly and monthly

dummies

Log (Price)

Sales

Weekly time

trend

Log (Price) Sales

Yearly and monthly

dummies

Log (Price) Sales

Weekly time

trend

%0.092

%0.131

0.141

%0.156

0.012

%0.048

0.014

%0.053

0.067

0.058

0.072

0.062

Note: None of the estimates in the table is statistically significant.

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

10

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

smooth, outside competition should remain stable

within the short time window before and after the

channel structure change. Results are reported in

Table 6. The effects of the channel structure change

(first two rows in the table) are similar to the price

and sales regression results in Tables 3 and 4, though

the coefficients for the watch category are insignificant because the number of observations is much

smaller in these regressions.

In summary, our empirical results are consistent

with the prediction that sales will increase due to

manufacturers increasing service provision under

MMR as suggested by Jerath and Zhang (2010). However, due to data limitations we cannot completely

rule out all of the alternative explanations including

retailer specific effects that are unobserved by the

researchers.

5. Empirical Tests: Heterogeneity in

Reponses across Brands

For analytical tractability Jerath and Zhang (2010) do

not consider heterogeneity across manufacturers. In

reality, manufacturers may have different competitive

strengths and their products may target different consumer segments. As a result of these differences, manufacturers may face different competitive pressures

and may respond differently to a shift from RMR to

MMR.

To explore this possibility, we estimated a latent

class regression model as follows. We assumed that

there exist C latent classes of brands. For brand i, the

probability that it belongs to class c is pic. The effects

Table 6 Price and Sales Regression 1 Month Before and After the

Channel Structure Change

Parameters

(1) Price regression

Channel structure change

(2) Sales regression

Channel structure change

Log(Own Price)

Brand 1

Brand 2

Brand 3

Brand 4

Brand 5

Brand 6

Brand 7

Brand 8

Brand 9

Brand 10

Brand 11

Brand 12

Brand 13

Log(Cross Price)

Cell phone category

%0.078***

0.082**

%0.739

%1.398

%1.505***

%0.875**

%2.463**

%2.553***

%1.702***

%1.654***

%3.140***

%3.264***

N/A

N/A

N/A

0.493

*, **, ***significant at 0.10, 0.05, 0.01 level.

Watch category

%0.032

0.054

%0.032

%0.177***

%0.180***

%0.294*

%0.461***

%0.358***

%0.537***

%0.576***

%0.567***

%0.624***

%1.219***

%0.833***

%2.084***

0.043

of the channel structure change on prices and sales

are class-specific. That is, we re-specify Equation (1)

as

C

X

di Z0it qc hc sit tcit ( 1 fi belongs to class cg

pit

c1

10

and Equation (2) as

qit

C

X

bi Xit0 vc cc1 pit cc2 cpit dc sit ncit

c1

( 1fi belongs to class cg;

20

where 1{} is an indicator function that is equal to 1

if the expression inside the bracket is true, and zero

otherwise. The heterogeneity in the effects of the

channel structure change across brands is captured

by the class-specific parameters hc and dc in the

above equations.

We estimated the price and sales functions simultaneously using the maximum likelihood method. The

maximum likelihood function is

N

X

log

i1

C

X

c1

(ff qit % bi %

Pci (

T

Y

t1

Xit0 vc

ft pit % di % Z0it qc % hc sit

cc1 pit

cc2 cpit

!

% d sit ;

c

in which f and ff are the density functions for the

error terms and , respectively, where we assume

t ) N0; r2ct and n ) N0; r2cn . The parameters to be

estimated include pic, qc, hc, vc, c1c, c2c, dc, r2ct and r2cn

(where c = 1, . . ., C), as well as fixed effects di and bi.

To determine the number of classes, we repeatedly

estimated the model with C = 2, 3, 4, and 5. As shown

in the first two columns in the upper panel of Table 7,

Table 7 Results of Selecting the Number of Latent Classes

The value of

information criteria

Number of

latent classes

AIC

Cell phone category

2

1387.71

3

1647.98

4

1757.43

5

1832.30

Watch category

2

5451.26

3

5250.46

4

5327.14

5

5536.53

The p-value of

statistical test

BIC

Bootstrapped parametric

likelihood ratio test

975.98

1174.21

1266.74

1324.69

0.00

0.00

1.00

1.00

5869.87

5722.13

5817.51

5982.94

0.00

0.00

0.23

1.00

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

11

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

Table 8 Estimation Results of the 3-Class Model

Cell phone category

Parameters

Channel structure change on prices

Channel structure change on sales

Log(Own Price)

Log(Cross Price)

Advertising

New models

The belonging of each brand based

on the highest probability

Class 1

%0.259***

0.109***

%1.983***

1.338***

0.382***

0.097***

5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Watch category

Class 2

Class 3

Class 1

Class 2

Class 3

%0.030

0.063**

%1.228***

0.713**

0.034

0.010

4

%0.048*

0.025**

%1.178***

0.237

0.213***

0.135***

1, 2, 3

%0.275***

0.216***

%1.515***

1.096***

0.215***

N/A

11, 12, 13

%0.069***

0.141***

%0.470***

0.024

0.113**

N/A

4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

0.212***

0.118***

%0.272

0.012

0.204***

N/A

1, 2, 3

*, **, ***significant at 0.10, 0.05, 0.01 level.

the two commonly used model selection criteria,

Akaikes Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian

Information Criterion (BIC), suggest that two classes

are sufficient to describe the heterogeneity in the cell

phone category. The recently developed Bootstrapped

Parametric Likelihood Ratio Test (the third column),

which tests the model with C classes to a model with

C % 1 classes, however, suggests that the 3-class

model significantly captures more brand heterogeneity based on the p-value (0.00). For safetys sake we

choose the 3-class model.

The left panel (the first three columns) in Table 8

reports the key estimation results for the 3-class case

of the cell phone category. The last row shows which

brands belong to each of the three classes, based on

the estimated probability pic. For Class 1, the coefficient of the channel structure change on prices is significantly negative, and the effect on sales is

significantly positive. For Class 2, the effect on sales is

significantly positive but the effect on prices is

insignificant. The effect on sales is also positive and

significant for Class 3, but the magnitude is the smallest among the three classes. The effect on prices for

Class 3 is negative and marginally significant. Overall, the results show substantive differences between

the various classes of brands. The effect of the channel

structure change are the strongest for Class 1 brands.

Table 1 shows that brands in this class (brands 510)

have a much smaller market share than brands 14,

which belong to Classes 2 and 3. The estimated intercepts of brands 510 in the sales regression (not

reported) are also significantly smaller. Furthermore,

Table 8 shows that the demand of Class 1 brands is

more price sensitive and greatly impacted by competitors prices.5

We then applied the same latent class regression to

the watch category. As shown in the lower panel of

Table 7, AIC, BIC, and the Bootstrapped Parametric

Likelihood Ratio Test all suggest the 3-class model

best fits the data. The right panel (Columns 46) in

Table 8 reports the key estimation results. Similar to

the cell phone category, there are significant variances

across the classes. The sales increases and price

decreases are the largest for Class 1. In comparison to

the other two classes, brands in this class (brands

1113) have the smallest share in terms of sales revenue (see Table 2). Table 8 also shows that the

demand for these brands is more price sensitive and

greatly impacted by competitors prices. It is interesting that the prices of Class 3 brands (brands 13)

increase after the channel structure change. One possible reason is that these brands are very luxurious

and conspicuous products (as the average retail prices

of these three brands are significantly higher than that

of other brands); thus, the manufacturers may be concerned with the maintenance of brand equity and

therefore be reluctant to engage in price promotions

under MMR. This finding is consistent with industry

evidence (OConnell and Dodes 2009, Dodes and Passariello 2011).

The heterogeneous responses across brands are

fairly consistent between the cell phone and the watch

categories. In general, brands with higher own-price

and cross-price elasticities lower price more after the

channel structure switch. Their sales also grow more

due to increased service. To understand how these

findings can be generalized to other categories and

markets, it is important to explore analytically why

these demand factors lead to the asymmetry in manufacturers responses. Given that our research focus is

empirical, we leave this task to future research.

6. Conclusions

MMR has become a prevalent retailing system in Asia

and is growing in popularity in other parts of the

world including the United States. Under this system,

retailers delegate many decisions, including inventory management, pricing and sales staff hiring, to

manufacturers. MMR has been proposed as a potential solution for channel conflicts between retailers

and manufacturers.

We empirically study the effects of a switch from

RMR to MMR on retail prices and sales in the cell

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

12

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

phone and watch categories within a leading Chinese

department store. We find that after changing to

MMR the average retail price across all brands

decreases by about 11% in the cell phone category

and by 34% in the watch category. These price

decreases lead to increased sales. Beyond the price

driven demand effect, we also find an additional 9

10% net gain in retail sales for the cell phone category

and 1117% for the watch category. These results are

consistent with the analytical results of Jerath and

Zhang (2010) that manufacturers are incentivized to

provide better in-store service.

We use data from another department store and

from other categories in the same store as controls.

We also adopt the regression-discontinuity

approach to test our findings. These additional analyses help exclude several alternative explanations. We

further use a latent class model to study how brand

heterogeneity may lead manufacturers to respond differently to the change in channel structure. For the cell

phone category, we find that while the results are consistent across most brands, there are no significant

price cuts for major and price-inelastic brands. For the

watch category, while low-tier brands cut prices,

high-tier brands increase prices after the channel

structure change.

To our knowledge this is the first study that provides direct empirical comparisons between RMR

and MMR systems. There have been many theoretical

works in marketing, operations and economics

research focusing on channel coordination issues

under various types of manufacturer-retailer contracts. We consider it important from an academic

perspective to empirically test the predictions generated from different theories. We also believe that our

findings are important for managers outside China

(e.g. in the U.S.) since the MMR systems are becoming

more prevalent in the retail industry.

There are a few notable limitations to this study.

We have not considered the impact of this new type

of retailing system on retailer competition and on

market structure. It would also be interesting to examine who benefits most from the channel structure

change, manufacturers, the retailer, or consumers?

Recent work by Li and Moul (2015) addresses those

questions with a structural modeling approach. In

addition, while we find that MMR leads to increases

in sales above and beyond what can be explained by

price changes, due to data limitations we are unable

to disentangle the various factors that cause the

changes. Further scrutiny of the role and impact of

the revenue sharing contract between manufacturer

and retailer is also warranted (Wang et al. 2004).

Finally, we find substantive asymmetric effects across

different types of brands. It is important to develop a

theoretical model to formally study what are the

important factors that lead to such asymmetric

effects.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the Department Editor and the

Senior Editor for their invaluable guidance, and the two

anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. We also

thank participants at 2008 Marketing Science Conference

and Marketing Scholar Forum VIII, and seminar participants at Fudan University and University of Minnesota for

their thoughtful comments on previous versions of this

article.

Notes

1

During our sample period, the store only sold cell phone

hardware. Consumers had to subscribe to wireless

services from wireless communications service providers

separately.

2

Their model assumes that retailers charge manufacturers an up-front fixed rent, which is different from the

MMR system under which retailers charge manufacturers a percentage of sales revenue. We develop an analytical model where two (symmetric) manufacturers sell

to one retailer. The retailer initiates a revenue-sharing

contract to manufacturers under the constraint that manufacturers profits are positive. We find that the equilibrium retail prices under MMR are always lower than

that under RMR. Since this model set-up is similar to

theirs, we choose not to include it in this study to save

space. Detailed results are available from the authors

upon request.

3

The store does not carry cell phones so we cannot compare for the category.

4

That said, we cannot rule out the possibility that the

demand or cost shocks are specific for the store and for

the cell phone and watch categories only.

5

To investigate whether these results are driven by revenue-sharing in contracts, we further collect information

on revenue sharing for the cell phone category. There are

variations across brands. Brands 1, 2, and 4 pay 22.5% revenues to the store. Brands 3 and 7 pay 25%, and the rest

of five smaller brands pay 26%. If the price changes were

only caused by the revenue sharing contract, brands 1, 2

and 4 would lower prices more than other brands after

the channel structure switch, since they pay less to the

store. Results from Table 8, however, show that Class 1

brands (brands 510) lower prices the most after the

switch. This suggests that revenue sharing contracts and

price changes may be simultaneously driven by brandspecific factors: Since Class 1 brands have small market

shares (see Table 1), they have lower bargaining power

when negotiating the contract with the department store.

Also, since the price sensitivity of those brands is higher

than for other brands (see Table 8), they have greater

incentive to lower prices to compete for market share

shares after the channel structure switch. Had the revenue

shares been fixed to be the same for all brands, Class 1

brands would have lowered prices even more than in the

results in Table 8.

Please Cite this article in press as: Li, J., et al. What Happens When Manufacturers Perform The Retailing Functions?. Production and

Operations Management (2016), doi 10.1111/poms.12549

Li, Chan, and Lewis: Manufacturers Performing the Retailing Functions

Production and Operations Management 0(0), pp. 113, 2016 Production and Operations Management Society

References

Abhishek, V., K. Jerath, Z. J. Zhang. 2015. Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Management

Sci. forthcoming.

13

Kurtulus, M., R. C. Savaskan. 2013.Drivers and implications of

direct-store-delivery in distribution channel. Working paper,

Owen Graduate School of Management, Vanderbilt University.

Arya, A., B. Mittendorf, D. E. M. Sappington. 2007. The bright

side of supplier encroachment. Mark. Sci. 26(5): 651659.

Kurtulus, M., A. Nakkas, S. Ulku. 2014. The value of category

captainship in the presence of manufacturer competition.

Prod. Oper. Manag. 23(3): 420430.

Aviv, Y., A. Federgruen. 2003. The operational benefits of information sharing and vendor managed inventory programs.

Working Paper, Olin Business School, Washington University,

St. Louis.

Lee, H. L., P. Padmanabhan, S. Whang. 1997. Distortion in a supply

chain: The bullwhip effect. Management Sci. 43(4): 546558.

Lee, H. G., T. Clark, K. Y. Tam. 1999. Can EDI benefit adopters?

Inf. Syst. Res. 10(2): 186195.

Cachon, G. P. 2003.Supply chain coordination with contracts. de

Kok A. G., S. C. Graves, eds. Supply Chain Management:

Design, Coordination and Operation. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, North-Holland, 229339.

Li, J., C. C. Moul. 2015. Vertical contract, customer service, and

social welfare in a chinese mobile phone market. Int. J. Ind.

Organ. 39(March): 2943.

Cachon, G. P., M. Fisher. 1997. Campbell soups continuous

replenishment program: Evaluation and enhanced inventory

decision rules. Prod. Oper. Manag. 6(3): 266276.

Li, Z., S. M. Gilbert, G. Lai. 2014. Supplier encroachment under

asymmetric information. Management Sci. 60(2): 449462.

Mahajan, S., G. van Ryzin. 2001. Stocking retail assortments under

dynamic consumer substitution. Oper. Res. 49(3): 334351.

Cachon, G. P., M. A. Lariviere. 2005. Supply chain coordination

with revenue-sharing contracts: Strengths and limitations.

Management Sci. 51(1): 3044.

Chen, X., G. John, O. Narasimhan. 2008. Assessing the consequences of a channel switch. Mark. Sci. 27(3): 398416.

Mishra, B. K., S. Raghunathan. 2004. Retailer- vs. vendor-managed

inventory and brand competition. Management Sci. 50(4): 445

457.

Choi, S. C. 1991. Price competition in a channel structure with a

common retailer. Mark. Sci. 10(4): 271296.

Moorthy, K. S. 1987. Managing channel profits: Comments. Mark.

Sci. 6(4): 375379.

Clark, T. H., J. Hammond. 1997. Reengineering channel reordering processes to improve total supply chain performance.

Prod. Oper. Manag. 6(3): 248265.

Rey, P., J. Stiglitz. 1995. The role of exclusive territories in producers competition. Rand J. Econ. 26(Autumn): 431451.

Shepard, A. 1993. Contractural form, retail price, and asset characteristics in gasoline retailing. Rand J. Econ. 24(Spring): 5877.

Coughlan, A. 1985. Competition and cooperation in marketing

channel choice: Theory and application. Mark. Sci. 4(2): 110

129.

OConnell V., R. Dodes. 2009.Saks upends luxury market with

strategy to slash price. Wall Street Journal, February 9, 2009.

Available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB12341353248676

1389 (accessed date November 9, 2015).

Dodes, R., C. Passariello.2011.Luxury brands stake out new department store turf. Wall Street Journal, May 4, 2011. Available at

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704740604576

301113906906234 (accessed date November 9, 2015).

Dong, Y., M. Dresner, Y. Yao. 2014. Beyond information sharing:

An empirical analysis of vendor-managerd inventory. Prod.

Oper. Manag. 23(5): 817828.

Jerath, K., Z. J. Zhang. 2010. Store-within-a-store. J. Mark. Res.

47(4): 748763.

Jeuland, A., S. Shugan. 1988. Channel of distribution profits when

channel members form conjectures. Mark. Sci. 7(2): 202210.

Kadiyali, V., P. Chintagunta, N. Vilcassim. 2000. Manufacturerretailer channel interactions and implications for channel

power: An empirical investigation of pricing in a local market. Mark. Sci. 19 (2): 127148.

McGuire, T. W., R. Staelin. 1983. An industry equilibrium analysis