Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

RLCL 5584 Final Paper

Enviado por

Spenser D. SloughDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

RLCL 5584 Final Paper

Enviado por

Spenser D. SloughDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Models of Heritage Building &

Proliferation:

Christiansburg Industrial Institute, Museum

Interpretation, and Recommendations for Future

Success

Spenser D. Slough

RLCL 5584: Museum Interpretation

Final Paper

May 2016

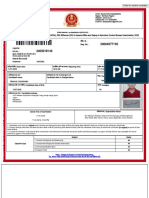

Edward A. Long

on the campus of

Christiansburg

Institute. Photo

(February 2016).

Building (1927),

the former

Industrial

by author

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

INTRODUCTION

On a partly sunny afternoon in March my classmates and I sat patiently at the lot off

Scattergood Drive. We were waiting to have one of the elders of the Christiansburg Institutea

former all-black school and campus in Christiansburg, VA to meet with us to open the

smokehousea rehabilitated, brick structure once used as an early twentieth-century

smokehouse on the campus now used as a small museum. As she slowly approached our group,

we could tell she was not having a good day. She grudgingly unlocked the smokehouse and we

began photographing the small museum. As we began, we could not help but hear her murmur:

Pictures, yall always take them pictures and yet we never seen nothing come of it.

Assigned to the Christiansburg Institute as a museum interpretation intern tests the bonds

of the public with the academic, the local with the institutional, the forgotten with narrators. As

one of the few remaining vestiges of African American post-antebellum education centers in

southwest Virginia, the Christiansburg Industrial Institute (CI) sits in the midst of national issues

of museum interpretation, preservation, and public engagement. In previous decades concerns of

preserving heritage sites such as CI seemed nonexistent. In 2016, the concern is present, yet the

action taken remains scant if nonexistent. CI has for several years received grants, interns,

artifact donations, and support from a major state university. As a result, CI has small museum

with a maximum capacity of 10 guests, an emptied two-story and a half former school building, a

foundation with inconsistent objectives and means, and an alumni base wary of assistance. In

sum, it is an oncoming public historians gold mine. Seriously.

My experience as a CI intern demonstrates the enormous value of seeing not only the

hidden histories of people but also the obscured relationships within the realm of public history.

Abundant resources, impassioned students, an established foundation, and alumni recognition

could have not produced, as of today, anywhere near a final product. Students typically witness

scenarios such as these with pessimism and contempt. I argue that doing so veils a public

2

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

historian from the overwhelming pervasive realities faced by museums across the nation. While

the majority of my contributions centered on finding existing similar corollaries, I nevertheless

witnessed the extant logistical shortcomings and culture present within CI. This essay paints an

introspective of CI and suggests several courses of action based on mine and my internship

teams observations and proven tactics implemented by museums across the nation.

CHRISTIANSBURG INDUSTRIAL INSTITUTE-OVERVIEW

The history of the Christiansburg Industrial Institute (CI) can be traced to just the closing

of the American Civil War. At the wars end a national program for educating newly-freed

African Americans commenced under the auspices of the Freedmens Bureau. In 1866, Union

army officer and assistant superintendent of the Freedmens Bureau, Capt. Charles S. Schaeffer

chartered CI as a primary school for primary-aged African American men and women. CIs

founding is significant as it opened five years before the establishment of public schools in

Montgomery County. Shortly after CIs founding, Schaeffer opened the Christiansburg African

Baptist Church. In 1873 oversaw the building of the first building solely dedicated for school

purposes. By 1885 the structures attendees outgrew the building, and a two and one-half-story

school was built along with a Memorial Church.

In 1895 the Friends Freedmens Association, a Philadelphia-based organization of the

Society of Friends and lifelong supporter of CI, convinced Booker T. Washington to take over the

supervision of the school, resulting in expanded curriculum similar to that of Tuskegee and

Hampton. CI continued to grow over time and necessitated the purchasing of 87 acres of land on

the north bank of Crab Creek. Tuskegee Institute graduate, Edgar A. Long became principal of

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

CI in 1906 and would oversee the school having the highest ranking of schools evaluated by

Julius Rosenwald, businessman and philanthropist.1

At the time of Longs death in 1924, CIs campus included the school, Baily-Morris Hall,

a hospital, and a farmers cottage. Abraham M. Walker would succeed Principal Long in 1925,

and it was under his tenure plans for a new school building commenced. In honor of Principal

Longs contributions to CI, the new schoolhouse was erected and named the Edgar A. Long

Building. The Long Building opened for classes in December 1928. In addition to typical courses

of a rounded curriculum, building also offered classroom space for instruction in sewing,

cooking, and agriculture. Throughout the years several additional buildings would house these

vocational courses, in addition to providing formal housing for students.2

21ST-CENTURY MUSEUM & HERITAGE SITE

In 1976, the Christiansburg Institute Alumni Association (CIAA) formed to gather alumni and

preserve the legacy of their alma mater, and in 1996, founded Christiansburg Institute, Inc. (CII)

to manage the property and buildings remaining from the campus, donated by Christiansburg

businessman Jack Via in support of CIAAs dream to create a museum and cultural center at the

site. CIAA and CII sponsor four annual events together for fellowship and fundraising. Today,

both CIAA and CII work together to craft a vision for the museum, use and operation of its

buildings, and gain broad public recognition of their goals and services.

Anyone visiting Christiansburg today, however, would hardly notice the monstrous,

classical revival-inspired Edward A. Long building or the smokehouse on Scattergood Drive; the

two sole structures remaining from the original campus. Physicality of these aboveground

1 National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), Edgar A. Long Building, Christiansburg, Montgomery

County, Virginia, National Register #1545008 (2001)

http://dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Counties/Montgomery/1545008_EdgarA.Long_Building_2001_Final_Nomination.pdf (Accessed on 5/1/16).

2 Ann Swain, Christiansburg Institute: From Freedmans Bureau Enterprise to Public High School,

Masters Thesis, Radford College (Radford, VA, 1975).

4

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

structures notwithstanding, there are several other issues plaguing CII in producing a viable

heritage museum. For one, public recognition of CI is almost entirely concentrated within

Montgomery County residents, local town leaders, and the near dozen academics from Virginia

Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) that have partnered with CII for

fundraising, technological pursuits, and museum consultation. As mentioned, the sole public

exhibit displaying CIs history is confined to the former campus smokehouse: today an adaptive

reuse venue stuffed with memorabilia, didactics, photos, a large guest book, and the conventional

museum glass cases, all within a max ten- person capacity space. Similarly, the smokehouse is

not regularly staffed nor does it have announced hours of accessibility.

Similar shortcomings are present within CIs social networking, communication, and

digital outreach. A ca. 2010 website, as of today (christiansburginstitute.org), has lost its domain

rights to Word Press blog. A seemingly up-to-date Facebook website is the by the far the most

readily accessible means of internet-based information and orientation to CI and the museum.

Nevertheless, Christiansburg Institute: Revitalizing a Legacy, has not received updated

statuses, comments, or administrative changes since September 30, 2015. The sole silver lining

in digital breakthroughs for CI rest in recent developments in augmented reality-based

technologywhere the users view of the real world is enhanced with additional objects and

information on a viewing screen.3

This was the museum industry that I and my project teamJenny Nehrt, Jeffrey Attridge, and

Mikhelle Taylorinherited and worked with throughout Spring 2016. Originally, we all believed

we would be involved in the rotation of the smokehouse exhibits materials, update or even

temporarily manage the Facebook site, and possibly even present CII and/or CIAA with some

proposals for future fundraising. We soon discovered that doing such typical museum

3 See New mobile app uses augmented reality to enhance learning experiences at historic sites, VTNEWS (May 5,

2014): https://vtnews.vt.edu/articles/2014/05/050514-engineering-historyappcburg.html.

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

internships tasks would neither be sufficient nor worthwhile, as deep entrenched issues and

politics proved our efforts would soon be forgotten and have an ephemeral legacy. In short, all

four of us came to the consensus that doing the typical semester-long internship work would be

a disservice and would belie our mandate and principle as public scholars. As exemplified in our

April 2016 poster at VT Engage:

As we began to work on the project and reflect on what we were learning from the course,

however, we started to better understand the demands of ethical curatorship when working with

the memories and artifacts that are precious to individuals as a part of their identity and

community history.4

CHRISTIANSBURG INSTITUTE EVALUATION & GOALS

Our teams preliminary evaluation of CIs museum initiatives revealed a history of overambitious goals and timelines, brokered communication, and conflicts of shared and unshared

authority. Since CII began formulizing a heritage museum in honor of the CIs outstanding

historical regional significance almost all energies, fundraising, and passions have aimed toward

the restoration of the Edgar A. Long Building. In 1995 CII funded and contracted an architectural

survey and study of the former school building to determine the approximate financial costs to

fully rehabilitate or restore the structure as a heritage museum space. The results of the 1995

survey indicated that at least $1.5 million would be needed to renovate the Long building. The

first major fundraising initiatives from 1995 to 1996 raised over $15,000, that subsequently

remitted the costs to conduct further architectural and environmental studies of the building and

its landscape. From 1997 to 1998 over $41,000 were raised from grants, Virginia Tech donation,

and individual giving. While well far beyond their monetary goals, funds were spent to conduct

more surveys to have the Long building listed on the National Register of Historic Places

4 Jeffery Attridge, Jenny Nehrt, Spenser Slough, and Mikhelle Taylor, PreSERVation: Community

Partnership and Curatorship in Local Museum Development, Poster Presentation (April 26, 2016).

6

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

(NRHP) in 2001. Even on the application to NRHP CIs goal remained clear that plans were to

use it as a museum and community learning center.5

Learning the history behind the museums efforts to restore the Long building led us to a set of

concerns. The difference between timelines and outcome expectations between the different

organizational partnerships necessary for the realization of CIIs dream has overwhelmed the

alumnis role and voice in developing the museum, especially since the restoration of the Edgar

A. Long Building would require substantial outside funding. Making matters worse, good

intentions from outside partners have caused heated debates over authority and ownership. Since

becoming the superintendent of Montgomery County Public Schools, Dr. Mark Miear has sought

to publicly recognize and exhibit CIs history. Supposedly, Dr. Miear has secured several

thousand dollars for such an initiative. However, he envisions that Christiansburg High School,

located a mile away from the CI campus, would be the venue of choice to serve as the museums

home. Not only would this relegate the original campus site into a state of irrelevance, Dr.

Maiers proposal has been constructed almost entirely without the primary stakeholders: CII and

CIAA. Symbolically, this repositioning of an African American, Jim Crow-era educational

centers history would be tantamount to the historical conditions that precipitated the eventual

demise of CI after desegregation.

Based on these mentioned concerns and issues, our team began to rethink our semester

goals. Most of all, we wished to provide a tangible result from our participation, one that CI feels

is beneficial to their work and preserves their ownership and authority in the final outcomes.

Thus, each of us decided to focus on individual aspects to meet these tangible outcomes: 1) a

reformatted digital museum with an easier, user-friendly platform for future staff and volunteers,

2) short-term grant guidance to identify smaller stepping stone grants, 3) public relations

5 Christiansburg Institute, Where the Past and the Future Learn from Each Other.; NRHP, Edgar A.

Long Building, 1.

7

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

materials aimed toward providing potential donors with broad information packets, and 4)

research, analyze, and compile information, strategies, and tactics used by extant surrounding

heritage museums that also emphasize African-American educational history. The fourth

individual project was my initiative, and is described in the remainder of this paper. In

completing each of our four initiatives, our group operated under some guiding theoretical

frameworks of museum interpretation we studied throughout the semester. We identified two

major theoretical framework themes to guide our interpretation and completion of our initiatives:

power & authority and community & memory.

MUSEUM INTEPRETATION FRAMEWORKS

The American museum is a creature of the people while staff are the transmitters of

peoples will. As such, the museum is a construct contingent upon temporal and spatial changes

in use and attitudes over time, predominately circling around questions of power and authority.

Since WWII the museum entity in America has progressed from collection to educational space,

from homogeneous to heterogeneous in narrative perspectives, and from insular to expansive in

the places that museums can reach out to through a variety of medias. Yet, these

transformations have not been smooth nor immediate. Rather, transformations in the role and

place of museums has rested on the engagement and contribution of visitors. As a result, a

delicate balance between power holders and authority figures in public service and cultural/

historic preservation.6

Museums of today, argues Steve Dubin, are hotbeds for conflicts over who controls

history and culture of the community. National conversations over revising history or preserving

cultural heritage persisted over time, yet museums and institutions continued to solidify culture,

6 Stephen Weil, From Being About Something to being for Somebody: The Ongoing Transformation of

the American Museum, in Reinventing the Museum: The Evolving Conversation on the Paradigm Shift.

Ed. Gail Anderson, (Lanham, Md: AltaMira Press, 2012):170-190

8

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

endow it with a tangibility.7 As centers of learning rather than shrines, museums of today are

public forums for debating the ideas that emanate from the objects exhibited So, why are

museums so controversial? Ironically, says in Dubin in Displays of Power, the further museums

sought to better represent, chronicle, revise, and display the past the more controversial they

became.8

Whether in local historical societies, culture heritage centers, house museums, the proper

purpose of museums has shifted over time. In many of these institutes battles have ensued over

balancing ideas and things, while also aiming to avoid replicating the features for which

museums have been critiqued. In other words, museums aim to strike the proper balance

between memory and community involvement. How can museum staff like those at CI create

historic spaces and interpretation rooms depicting African-American heritage through

educational history as one of pride and resistance but still within the context of Jim Crow Era? Is

it possible to utilize material culture to challenge historic racial norms using the same artifacts

that reinforced racial inequality? Not all components of national history espouse uplifting,

patriotic tunes National tragedies are memorialized and eventually incorporated into museum

settings. Yet, says James Gardner and Sarah Henry, how if at all do museums collect stuff

pertinent to a national disaster? Memorializing the tragedy of September 11, 2001, for instance,

raises not only the question of whether to collect, but if authenticity is and can be preserved

when skirted against ethical concerns. Unlike artifices created in Boston to memorial Holocaust

victims, a proposed museum in New York City, itself touched in every aspect by the historical

events of 9/11, would require collecting, conserving, and teaching through quotidian items:

7 Steven C. Dubin, Display of Power, Power: Memory and Amnesia in the American Museum, (New

York: New York University Press, 1999): 2.

8

9

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

clothes, architectural fragments, faxes, and scorched staircase signs. Additional concern is

whether memorial-based museums constitute classification as a history museum or memorial.

Where does memory end and history begin, or, if neither have an exact point of existence, how

can, if at all, history compliment memory and vice versa? The stuff museums collect, conserve,

and exhibit raise many of these inquiries, but all relate back to what and whose history is being

told and whether it is represented authentic.9

As Kim Christensen points out, the material world of past peoples is not a mere

reflection of meaning, but also the multiple ways those meanings are processed and changed

over time. So, perhaps the stuff we collect and preserve in museums are not always supposed to

align. It is why the alternate meanings imbued to material culture through practice, are

poignant. They affirm a key foundation of museums as contemplative spaces, says museum

director Nina Simon. In her work The Participatory Museum she affirms that the role of local

contributions is vital, if not a prerequisite to for a successful museum. From handwritten

placards, to self-documentation reports, small murals, or even craft corners and workshops, the

involvement of the public within contained and outdoor spaces ensures a diversity of opinions

and affirmation that peoples voices are valued. This is where true power and authority lies.

Institutional leaders only retain such clout and respect once the public accepts this transference.10

STUDY & ANALYSIS OF HERITAGE CENTERS

In order to provide CI with the most holistic evaluation of how other heritage sites operate and

function, I selected three Virginia heritage sites to analyze based on self-selected criteria. One,

9 James B. Gardner and Sarah M. Henry, September 11 and the Mourning After: Reflections on

Collecting and Interpreting the History of Tragedy, The Public Historian 24 (2002): 41, 52.

10 Dan L. Monroe, and Echo-Hawk, Walter. Deft Deliberations. in Reinventing the Museum:

Historical Conversations on the Paradigm Shift. Ed. Gail Anderson. 325-330; Nina Simon, Open Letter

to Ariana Huffington, Edward Ruthstein, and Many Other Museum Critics. (2011); Reinventing the

Museum: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on the Paradigm Shift (Lanham, MD: AltaMira

Press, 2002): 108-110.

10

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

the site must have been affiliated at one point as an educational center for African-Americans.

Second, a center must still be in continuous operation and have consistent operational hours,

days, and/or seasons. Last, I sought to choose the closest sites in proximity to Christiansburg, as

this would provide my analyses the most accurate geospatial context. For sources, I consulted

websites and when possible had direct communication with staff members and volunteers. In my

evaluations, I based my analyses on the two theoretical themes of power & authority and

community & memory. The remaining pages provide a detail evaluation of the two most optimal

examples of success, while Appendix A provides a convenient chart that breaks down each sites

strengths, organized by columns in accordance with which theoretical theme they relate to.

Josephine School Community Museum

Based in Clarke County, VA in the town of Berryville is the Josephine School

Community Museum and Clarke County African-American Cultural Center. The museum is

housed in an 1882 rectangular, one-story, frame-building approximately 40ft. long and 30ft.

wide. The founders of the school were former slaves and freed persons of color who sought after

a grade school for children. In its formative years, it primarily provided basic reading, writing,

and arithmetic lessons. Under the leadership of Rev. Edward Johnson, a new building addition

was completed in 1930 to expand the student population. In addition, students at that time were

also provided high school education and the center was officially renamed the Clarke County

Training School. From 1949 to 1966, the school was known as Johnson-Williams High School.

Unlike Christiansburg Institute the school did not immediately shut down once Virginia schools

desegregated. After the integration of the public schools, it became the Johnson-Williams

Intermediate School and served students of all races from 1966 until it closed in 1987. In 1992

11

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

the county converted all remaining post-1930 structures on the school complex grounds into

senior citizen apartments. 11

In 1990, efforts by surviving alumni concentrated into creating the Josephine City School into a

museum and cultural heritage center. The newly created foundation raised enough money, near

$12,000 to conduct basic architectural and landscape surveys and historic restoration of the

school. Their efforts led to the schoolhouse being listed onto the NRHP and the Virginia

Landmarks Register in 1994. Before beginning any services or museum practices the foundation

ensured that their schoolhouse was renovated and that enough capital secured to support

educational and public outreach efforts. This ensured, according to acting museum director

Norma L. Johnson, that enough money was available to pursue smaller grants over time, while

still maintaining enough capital to begin providing a service.12 A takeaway that CII and CIAA

could extrapolate from this narrative is that museums can only operate once fully committed and

financially buttressed in all sectors. While many believed the museum could have opened in

1998, the foundation continued to pursue smaller grants to demonstrate the organizational

efficacy of their board, which contributed to their receiving much larger grants from the Virginia

General Assembly and the Clarke County Board of Supervisors. Only then, did the museum

officially open to the public on July 12, 2003. The building and center remains consistently open

to public Sundays 1 to 3 PM and open for other calendared events every year. According to their

website, the museum and centers mission statement is: is to create and manage a living

museum dedicated to restoring our original 1882 school house and sharing the people, objects,

11 "Josephine School Community Museum." History -. Accessed May 05, 2016.

http://www.millertek.net/JSCM/history.html.

12 Conversations with Norma L. Johnson, March- April 2016.

12

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

and stories that form the continuing legacy of Clarke County's

African American history

and heritage.13

Evaluation of the Josephine School

and cultural center reveals how a

small, low-cost museum can operate

and serve their public through a

wide variety of services. In power

and authority resources the museum

maintains a board of

local citizens that do not profess to specialty experts but just impassioned people who all want

the same things: preserve and serve. While museum and center maintain a board that directs

operations costs, overhead, and planning, the schoolhouse and center is largely an embodiment

of the wishes of its volunteers, visitors and guests; an integral component of what Nina Simon

has envisioned as a participatory museum where shared authority is maintained. For instance, the

most recent history and genealogical meetings on April 25th were led entirely by volunteers. The

product was three large poster boards of newly charted genealogies of some of the schoolhouses

earliest graduates. This is the museums version of rotating exhibit, but is one inherently the

product of the guests. In fact, the only permanent exhibit is an interactive school room with

original and replacement 1930s period school furniture and supplies. Last, it should be noted that

only the director is paid a salary for. The rest of the ten-person board and twenty-some docents

are volunteers.

The Josephine Museum and centers memory and community resources similarly mirror

the power and authority dynamics. Typical community events based on their (regularly updated)

calendar of events range from a monthly book club, Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebrations

13 "Josephine School Community Museum. Mission -. Accessed May 05, 2016.

http://www.millertek.net/JSCM/mission.html.

13

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

through folk songs and small-scale film festivals, history research groups, high school and

community college scholarship awards, picnics, and dramatic reading contests. To the typical

museum visitor these events may not seem essential to a heritage sites operation. Nevertheless,

it is important to realize they are events that foster community spirit and remembrance of the

sites historical significance as an educational center. While CII and CIAA is deadest on

reopening the Long building as a grand venue to serve as a regional center of history and culture,

it would not hurt for considerations, at least in the short-term, be geared toward temporary

bookings of community spaces in Christiansburg to host events like the ones just mentioned.

Wytheville Training School Cultural Center

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS FOR SUCCESS

Appendix A: Studied Heritage Centers

CENTER

Josephine School

Community Museum

(Berryville, VA)

HISTORY

AUTHORITY & POWER

RESOURCES

COMMUNITY &

MEMORY RESOURCES

-Founded 1882 as

grade school for

former slaves

-Non-Freedmans

Bureau affiliated

-Converted to

museum in 2003

-Brick structure built

Virginia Randolph

Cottage Museum

(Glen Allen, VA)

Wytheville Training

School Cultural Center

(Wytheville, VA)

1937 for Virginia

Randolph Training

Center

-Converted into a

museum in 1980s

-Founded in 1883

with Freedmans

Bureau assistance

-WTCC founded in

2001 as heritage and

14

S. Slough (2016)

Models of Heritage Building & Proliferation

cultural center and

educational conduit

Bibliography of Consulted Literature

Anderson, Gail, ed. Reinventing the Museum: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on the

Paradigm Shift. New York: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Black, Graham. Transforming Museums in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Routledge,

2012.

Boesen, Elizabeth. Peripheral Memories: Public and Private Forms of Experiencing and

Narrating the Past. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2012.

Cameron, Catherine M. and John B. Gatewood. Excursions into the Un-Remembered Past:

What People Want from Visits to Historical Sites. The Public Historian 22 (2000): 107127.

Dubin, Steven C. Displays of Power: Memory and Amnesia in the American Museum. New York:

New York University Press, 1999.

Falk, John H. and Lynn D. Dierking. The Museum Experience Revisited. Walnut Creek, CA: Left

Coast Press, Inc., 2013.

Gardner, James B. Contested Terrain: History, Museums, and the Public. The Public Historian

26 (2004): 11-21.

_______ and Sarah M. Henry. September 11 and the Mourning After: Reflections on Collecting

and Interpreting the History of Tragedy. The Public Historian 24 (2002): 37-52.

Simon, Nina. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0, 2010.

Wallace, Mike. Mickey Mouse History and Other Essays on American Memory. Philadelphia:

Temple University Press.

Weil, Stephen E. Making Museums Matter. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2002.

15

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Public History Cert., Internship Reflection Essay (2014)Documento11 páginasPublic History Cert., Internship Reflection Essay (2014)Spenser D. SloughAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Digital and Portable Museum in AppalachiaDocumento139 páginasThe Digital and Portable Museum in AppalachiaSpenser D. SloughAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Wythe County CraftsmenDocumento28 páginasWythe County CraftsmenSpenser D. SloughAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Wythe County Material CultureDocumento19 páginasWythe County Material CultureSpenser D. SloughAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- 20% DEVELOPMENT UTILIZATION FOR FY 2021Documento2 páginas20% DEVELOPMENT UTILIZATION FOR FY 2021edvince mickael bagunas sinonAinda não há avaliações

- Blueprint For The Development of Local Economies of SamarDocumento72 páginasBlueprint For The Development of Local Economies of SamarJay LacsamanaAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- European Gunnery's Impact on Artillery in 16th Century IndiaDocumento9 páginasEuropean Gunnery's Impact on Artillery in 16th Century Indiaharry3196Ainda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Drought in Somalia: A Migration Crisis: Mehdi Achour, Nina LacanDocumento16 páginasDrought in Somalia: A Migration Crisis: Mehdi Achour, Nina LacanLiban SwedenAinda não há avaliações

- Cruise LetterDocumento23 páginasCruise LetterSimon AlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- Schneider ACB 2500 amp MVS25 N - Get Best Price from Mehta Enterprise AhmedabadDocumento7 páginasSchneider ACB 2500 amp MVS25 N - Get Best Price from Mehta Enterprise AhmedabadahmedcoAinda não há avaliações

- Call LetterDocumento1 páginaCall Letterஉனக்கொரு பிரச்சினைனா நான் வரேண்டாAinda não há avaliações

- URP - Questionnaire SampleDocumento8 páginasURP - Questionnaire SampleFardinAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Solution Manual For Fundamentals of Modern Manufacturing 6Th Edition by Groover Isbn 1119128692 9781119128694 Full Chapter PDFDocumento24 páginasSolution Manual For Fundamentals of Modern Manufacturing 6Th Edition by Groover Isbn 1119128692 9781119128694 Full Chapter PDFsusan.lemke155100% (11)

- Ngulchu Thogme Zangpo - The Thirty-Seven Bodhisattva PracticesDocumento184 páginasNgulchu Thogme Zangpo - The Thirty-Seven Bodhisattva PracticesMario Galle MAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Fortianalyzer v6.2.8 Upgrade GuideDocumento23 páginasFortianalyzer v6.2.8 Upgrade Guidelee zwagerAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- School Form 10 SF10 Learners Permanent Academic Record For Elementary SchoolDocumento10 páginasSchool Form 10 SF10 Learners Permanent Academic Record For Elementary SchoolRene ManansalaAinda não há avaliações

- The Slow Frog An Intraday Trading Strategy: A Rules Based Intra-Day Trading Strategy (Ver 1.0)Documento17 páginasThe Slow Frog An Intraday Trading Strategy: A Rules Based Intra-Day Trading Strategy (Ver 1.0)ticman123Ainda não há avaliações

- La Fuerza de La Fe, de La Esperanza y El AmorDocumento2 páginasLa Fuerza de La Fe, de La Esperanza y El Amorandres diazAinda não há avaliações

- How To Get The Poor Off Our ConscienceDocumento4 páginasHow To Get The Poor Off Our Conscience钟丽虹Ainda não há avaliações

- English The Salem Witchcraft Trials ReportDocumento4 páginasEnglish The Salem Witchcraft Trials ReportThomas TranAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Organizational ChartDocumento1 páginaOrganizational ChartPom tancoAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- Remembering Sivaji Ganesan - Lata MangeshkarDocumento4 páginasRemembering Sivaji Ganesan - Lata MangeshkarpavithrasubburajAinda não há avaliações

- Homework 2.Documento11 páginasHomework 2.Berson Pallani IhueAinda não há avaliações

- Fs 6 Learning-EpisodesDocumento11 páginasFs 6 Learning-EpisodesMichelleAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Human Resource Management in HealthDocumento7 páginasHuman Resource Management in HealthMark MadridanoAinda não há avaliações

- James M Stearns JR ResumeDocumento2 páginasJames M Stearns JR Resumeapi-281469512Ainda não há avaliações

- Important PIC'sDocumento1 páginaImportant PIC'sAbhijit SahaAinda não há avaliações

- LectureSchedule MSL711 2022Documento8 páginasLectureSchedule MSL711 2022Prajapati BhavikMahendrabhaiAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- 1 292583745 Bill For Current Month 1Documento2 páginas1 292583745 Bill For Current Month 1Shrotriya AnamikaAinda não há avaliações

- STAFF SELECTION COMMISSION (SSC) - Department of Personnel & TrainingDocumento3 páginasSTAFF SELECTION COMMISSION (SSC) - Department of Personnel & TrainingAmit SinsinwarAinda não há avaliações

- SYD611S Individual Assignment 2024Documento2 páginasSYD611S Individual Assignment 2024Amunyela FelistasAinda não há avaliações

- ECC Ruling on Permanent Disability Benefits OverturnedDocumento2 páginasECC Ruling on Permanent Disability Benefits OverturnedmeymeyAinda não há avaliações

- Aclc College of Tacloban Tacloban CityDocumento3 páginasAclc College of Tacloban Tacloban Cityjumel delunaAinda não há avaliações

- Electronic Green Journal: TitleDocumento3 páginasElectronic Green Journal: TitleFelix TitanAinda não há avaliações