Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Climacteric Symptoms in Women

Enviado por

Amira Fatmah QuilapioDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Climacteric Symptoms in Women

Enviado por

Amira Fatmah QuilapioDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CLIMACTERIC 2009;12:404409

Climacteric symptoms in women

undergoing risk-reducing bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy

A. Benshushan, N. Rojansky, M. Chaviv, S. Arbel-Alon, A. Benmeir, T. Imbar and

A. Brzezinski

The Hebrew-University Hadassah Medical School, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Jerusalem, Israel

Key words: MENOPAUSE, RISK-REDUCING BILATERAL SALPINGO-OOPHORECTOMY, CLIMACTERIC SYMPTOMS

ABSTRACT

Background The most effective strategy for prevention of ovarian and breast cancer in

high-risk women is bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The inevitable consequence of the

procedure is early menopause with the associated climacteric symptoms. Little is known

about the nature of the symptoms in women who undergo risk-reducing bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy.

Objectives To compare the nature, frequency, severity, duration, and overall effects of

climacteric symptoms in a group of women who underwent preventive bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy as compared to women who experienced natural menopause.

Methods Forty-eight women at high risk for ovarian cancer who had risk-reducing

bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were compared to 60 postmenopausal women who

had natural menopause. The participants were interviewed about their climacteric

complaints, thoughts and feelings regarding the surgical procedure and their general

well-being. The climacteric symptoms were evaluated by a modified Greene Climacteric

Scale.

Results Surgical menopause, as compared to natural menopause, was associated with

more severe psychological, vasomotor and somatic climacteric symptoms (total score

17.36 vs. 8.65, respectively, p 5 0.001) and more significant sexual dysfunction (1.848

vs. 0.900, respectively, p 5 0.01). On a 010 scale, the satisfaction rate from the

surgical procedure was 8.23 + 2.21. The surgery did not affect the perceived quality of

life (p 0.347) and decreased the score of anxiety and cancer fear (from 7.75 + 3.31

preoperatively to 2.94 + 3.08 postoperatively, p 5 0.001).

Conclusions Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as compared to natural

menopause is associated with more severe climacteric symptoms. However, the

procedure does not interfere with the overall perceived quality of life and improves

the perception of cancer risk.

Correspondence: Professor A. Brzezinski, Hadassah University Hospital, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, EinKerem, Jerusalem, 91120 Israel

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

2009 International Menopause Society

DOI: 10.1080/13697130902780846

Received 29-10-2008

Revised 22-01-2009

Accepted 27-01-2009

Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and climacteric symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Climacteric symptoms adversely affect womens

quality of life and occupational functioning during

the menopause transition1,2. Vasomotor symptoms (i.e. hot flushes, night sweats and palpitations), psychological symptoms (i.e. dysphoria,

anxiety, irritability, instability, sleep disorders and

decreased libido) and urogenital atrophic symptoms are the early signs of estrogen deficiency.

Most women experience some climacteric symptoms (predominantly vasomotor symptoms) for 6

months to 2 years3,4. During natural menopause,

the onset of these menopausal symptoms is often

gradual over a period of a few months and they

resolve in 8590% of women within 45 years5. It

is a common clinical observation that, following

surgical menopause, these symptoms appear

abruptly and may be more severe in their intensity

and frequency, but this clinical observation has

not been adequately validated. There is also not

enough information about the attitudes and

tolerance of the climacteric symptoms by women

who undergo prophylactic bilateral salpingooophorectomy (BSO) as a measure to prevent

reproductive malignant tumors. We therefore

examined retrospectively the type, severity and

duration of climacteric symptoms in a group of

women who had preventive BSO as compared to

women who underwent natural menopause.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

One hundred and eight women were included in

this retrospective analytic study. We have compared a group of patients who underwent riskreducing BSO at The Hadassah-Hebrew

University Medical Center to a group of women

with natural menopause who attended the

menopause clinic in the same time period.

The study group consisted of 48 women who

underwent risk-reducing BSO and who agreed to

participate in the study. Thirty-three of them were

premenopausal at the time of risk-reducing BSO

and 15 were postmenopausal. The control group

included 60 postmenopausal women who visited

our gynecologic menopause clinic for various

climacteric complaints or for routine check-up

and had been amenorrheic for at 6 months.

Hormone therapy (HT) users were excluded from

this survey since women at risk for ovarian cancer

mainly avoid the use of HT, due to concern about

a possible additional risk of breast cancer.

We constructed a questionnaire which included

demographic and gynecologic data, information

Climacteric

Benshushan et al.

on the results of the surgery, and menopausal

symptoms at four time points: 1 month, 6 months,

and 1 year after the surgery or the womans last

menstrual period, and at the time of interview. We

have used a modified Greene Climacteric Scale6,7

for this evaluation. The questionnaires were

completed at an interview (performed by a

qualified single interviewer) after obtaining

informed consent for the survey. A few of

the questionnaires were filled via telephone

interview.

Statistical analysis

The w2 test was used to compare qualitative or

categorical variables. The T test was used for the

quantitative variables. The paired T test was used

to compare variables before and after within each

group. For evaluation of climacteric symptoms

over time, we used repetitive measures based on

the Greene Climacteric Scale7. The menopausal

symptoms were divided into three subgroups:

vasomotor symptoms, psychological symptoms,

and somatic symptoms (e.g. vaginal dryness).

The Greene Climacteric Scale score for each

subgroup at a given time was calculated by a

summation of grades given for each variable (0,

no symptoms; 1, mild symptoms; 2, moderate

symptoms; 3, severe symptoms). The results

presented for each subgroup are an evaluation of

the severity of the symptoms.

The data were analyzed using the Statistical

Package for Social Science (SPSS Base).

RESULTS

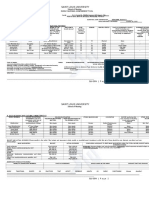

The demographic and clinical characteristics of

the study and the control groups are presented in

Table 1. These characteristics varied significantly

between the groups (e.g. mean age, time from last

menstrual period, personal and family history of

breast/ovarian cancer, and percent of BRCA

mutation carriers).

Fifteen women were excluded from the symptoms analysis due to being postmenopausal at the

time of risk-reducing BSO. Table 2 presents the

summary of the overall incidence of climacteric

symptoms in the study group and in the controls.

The psychological symptom scores were significantly higher in the study group at all time

points as compared to the control group (at time

of interview: 9.0606 vs. 3.9167, respectively,

p 0.001) (Table 3 and Figure 1).

The somatic symptoms were significantly different at 6 months (after cessation of menses or

405

Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and climacteric symptoms

Benshushan et al.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study and control groups. Data are given as

mean + standard deviation or percentage

Age (years)

Number of children

Time since LMP (years)

History of regular periods

Family history of ovarian/breast cancer

Family history of colon/uterine cancer

Personal history of breast cancer

BRCA mutation carriers

Hysterectomy

Study

Control

p Value

50.83 + 7.52

2.96 + 1.5

5.63 + 5.53

83.30%

79.20%

27.10%

50.00%

52.10%

50.00%

58.06 + 5.43

2.8 + 1.07

7.879 + 5.78

95%

26.70%

13.30%

6.70%

0%

8.30%

50.001

0.540

0.053

0.059

50.001

0.073

50.001

50.001

50.001

LMP, last menstrual period; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

Table 2 Overall prevalence of menopausal symptoms

in the risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

group and the controls. Data are given as % of the total

number of women in each group

Symptom

Study Control p Value

Heart beating

quickly/strongly

Feeling tense or nervous

Difficulty in sleeping

Excitable

Attacks of panic

Difficulty in

concentrating

Feeling tired/lack of energy

Loss of interest in

most things

Feeling unhappy

or depressed

Crying spells

Irritability

Feeling dizzy or faint

Pressure/tightness

in head/body

Parts of body feel

numb/tingle

Headaches

Muscle and joint pains

Loss of feeling in

hands or feet

Breathing difficulties

Hot flushes

Sweating at night

Loss of interest in sex

Vaginal dryness

Urinary incontinence

18.8

30.0

0.321

68.8

87.9

25.0

18.8

37.5

49.2

60.0

18.6

8.5

35.6

0.072

0.005

0.590

0.185

1.000

75.8

56.3

55.0

28.8

0.048

0.013

59.4

28.8

0.007

43.8

50.0

28.1

31.3

16.9

30.5

28.8

28.8

0.006

0.075

1.000

0.814

15.6

18.6

0.781

43.8

25.0

15.6

22.0

25.4

13.6

0.030

1.000

0.764

15.6

87.9

97.0

84.4

69.7

18.8

6.8

78.0

71.7

54.2

57.6

28.8

0.269

0.277

0.002

0.005

0.273

0.325

the risk-reducing BSO) (0.9483 for the study

group vs. 2.5455 for the control group, p 0.025)

and 1 year (1.1034 for the study group vs. 2.5938

406

for the control group, p 0.038) (Table 3 and

Figure 2).

The vasomotor symptom scores were significantly more severe in the risk-reducing BSO group

as compared to the controls (at time of interview:

3.94 vs. 2.05, respectively, p 5 0.001) (Table 3

and Figure 3).

We noticed a statistically significant difference

in sexual dysfunction at all time points in favor of

the control group (e.g. at time of interview: 1.85

vs. 0.90, respectively, p 5 0.01) (Table 3 and

Figure 4).

Data on the quality of life and satisfaction from

the risk-reducing BSO surgical procedure are

presented in Table 4. In 10.4% of the cases, there

were complications (mostly minor, e.g. local

infections, fever and minor bleeding). One case of

postoperative deep vein thrombosis was noted. The

overall satisfaction rate (on a 010 scale) was 8.23.

The perceived quality of life of the women

undergoing the operation decreased after the

surgical procedure (8.08 as compared to 8.52

preoperatively), but this difference did not reach

statistical significance (p 0.34).

As expected, the concern about ovarian cancer

decreased significantly after surgery (2.94 vs. 7.75

preoperatively, p 5 0.001) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

These results indicate that risk-reducing BSO as

compared to natural menopause is associated with

significantly higher prevalence and severity of

menopausal symptoms, which appear more

abruptly. Women who underwent the surgical

procedure and who were premenopausal at the

time of the operation were particularly vulnerable

to psychological distress; however, risk-reducing

BSO caused a significant decrease in anxiety and

fear of cancer risk.

Climacteric

Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and climacteric symptoms

Benshushan et al.

Table 3 The scores in the Greene Climacteric Scale

over time in the two groups

Mean score

Time after

LMP/surgery

Control

group

Study

group

p Value

Psychological score

At 1 month

At 6 months

At 1 year

Time of interview

2.389

3.551

3.896

3.916

4.697

8.818

9.687

9.060

0.022

0.001

50.001

0.001

Somatic score

At 1 month

At 6 months

At 1 year

Time of interview

0.694

0.948

1.103

1.783

1.151

2.545

2.593

2.515

0.206

0.025

0.038

0.290

Vasomotor score

At 1 month

At 6 months

At 1 year

Time of interview

2.220

2.724

2.551

2.050

2.363

4.181

4.451

3.939

0.772

0.003

50.001

50.001

Sexual dysfunction score

At 1 month

0.186

At 6 months

0.241

At 1 year

0.568

Time of interview

0.900

0.727

1.515

1.806

1.848

50.01

50.01

50.01

50.01

8.940

17.061

18.539

17.364

0.034

50.001

50.001

50.001

Total score

At 1 month

At 6 months

At 1 year

Time of interview

5.491

7.465

8.120

8.650

Figure 2 The somatic scores in the Greene Climacteric

Scale of the two groups

LMP, last menstrual period

Figure 3 The vasomotor symptom scores in the Greene

Climacteric Scale of the two groups

Figure 1 The psychological scores in the Greene

Climacteric Scale for the two groups

Figure 4 The sexual dysfunction scores in the Greene

Climacteric Scale of the two groups

Some of our results are consistent with previous

reports. Madalinska and colleagues8 reported

that women who underwent risk-reducing BSO

had worse somatic symptoms (p 5 0.001) and

increased sexual dysfunction (p 5 0.05) than

matched controls. Similar to our findings, riskreducing BSO was associated with fewer breast

and ovarian cancer worries (p 5 0.001) and more

Climacteric

407

Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and climacteric symptoms

Table 4 Pre- and postoperative attitudes and perceptions of 48 women who had risk-reducing bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy (on a 010 scale). Data are

given as mean + standard deviation

Satisfaction

Regret

Pre-operative quality of life

Postoperative quality of life

Pre-operative ovarian cancer worry

Postoperative ovarian cancer worry

8.23 + 2.21

0.77 + 2.25

8.52 + 2.59

8.08 + 2.88*

7.75 + 3.31

2.94 + 3.08**

*, No significant difference from pre-operation,

p 0.34; **, significantly different from pre-operation,

p 5 0.001

favorable cancer risk perception (p 5 0.05).

Eighty-six percent of the women in that study

would choose risk-reducing BSO again, and 63%

would recommend it to a friend with familial risk

of ovarian cancer. Fry and colleagues9 also found

that preventive BSO was associated with poorer

emotional and social functioning as compared to a

group of women who chose to have routine

screening follow-up and to avoid BSO. There

was also a trend towards more significant somatic

menopausal symptoms. Our study adds important

information to these findings by indicating that the

increased climacteric symptoms in women who

undergo risk-reducing BSO do not seem to

interfere with their overall perceived quality of life.

Meiser and colleagues10 found that, when performed postmenopausally, preventive BSO had no

negative impact on the womens libido and sexual

function. The participants reported that the procedure had decreased concern about cancer risk.

Consistent with our findings, Elit and colleagues11 and Robson and colleagues12 also reported

that the perceived risk for developing ovarian

cancer decreased significantly after surgery. However, Robson and colleagues12 reported that a

significant proportion of women who had riskreducing BSO (20.7%) continued to report

ovarian cancer-specific worries despite surgery.

As indicated, our patients were not using HT.

One report evaluated the effects of HT on similar

group of women. Madalinska and colleagues13

evaluated through a questionnaire, the endocrine

Benshushan et al.

symptoms and sexual functioning of 450 high-risk

women who had participated in a nationwide,

cross-sectional, observational study. They report

that 36% of the women had undergone riskreducing BSO and 64% had opted for conservative

follow-up. In the risk-reducing BSO group, 47% of

the women were current HT users. They found

significantly fewer vasomotor symptoms than in

non-users (p 5 0.05). However, compared with

premenopausal women who preferred follow-up,

oophorectomized HT users were more likely to

report vasomotor symptoms (p 5 0.01). HT users

and non-users reported comparable levels of sexual

functioning. They concluded that, although HT has

a positive impact on surgically induced vasomotor

symptoms, it may be less effective than is often

assumed. Symptom levels remain well above those

of premenopausal women undergoing screening,

and sexual discomfort is not alleviated by HT.

We are aware that our study has certain

limitations which necessitate further investigation

of the subject. The main limitations of study are

its retrospective analysis and the fact that the data

on climacteric symptoms were self-reported and

thus affected by recall bias. This may cause underor over-estimation of prevalence and severity of

the symptoms. However, we believe that this bias

may only marginally affect our results since

women usually remember vividly their climacteric

symptoms. This assumption was recently validated by the demonstration of strong correlations

between most estrogen exposure indices and selfreports14.

In conclusion, risk-reducing BSO as compared

to natural menopause is associated with more

severe somatic as well as psychological climacteric

symptoms. However, the surgical procedure does

not seem to interfere with the overall perceived

quality of life and improves the perception of

cancer risk which most women find worth the

burden of the symptoms.

Conflict of interest

Nil.

Source of funding

Supported in part by a

private donation from Mrs Rosalind Bassin of

Long Beach, CA, USA.

References

1. McKinlay SM, Brambilla DJ, Posner J. The

normal menopause transition. Maturitas 1992;

14:10315

408

2. Bachmann GA. Vasomotor flushes in menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:

S31216

Climacteric

Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and climacteric symptoms

3. Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, et al.

Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife

women. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:23040

4. Woods NF. Symptoms during the perimenopause: prevalence, severity, trajectory, and significance in womens lives. Am J Med 2005;

118:S1424

5. Kronenberg F. Hot flashes: epidemiology and

physiology. Ann NY Acad Sci 1990;592:5286

6. Greene JG. A factor analytic study of climacteric

symptoms. J Psychosom Res 1976;20:42530

7. Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric

scale. Maturitas 1998;29:2531

8. Madalinska JB, Hollenstein J, Bleiker E, et al.

Quality-of-life effects of prophylactic salpingooophorectomy versus gynecologic screening

among women at increased risk of hereditary

ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:68908

9. Fry A, Busby-Earle C, Rush R, Cull A. Prophylactic oophorectomy versus screening: psychosocial

outcomes in women at increased risk of ovarian

cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2001;10:23141

Climacteric

Benshushan et al.

10. Meiser B, Tiller K, Butow P, et al. Psychological

impact of prophylactic oophorectomy in

women at increased risk for ovarian cancer: a

prospective study. Psycho-Oncology 2000;9:

496503

11. Elit L, Epslen MJ, Butler K, Narod S. Quality of

life and psychosexual adjustment after prophylactic oophorectomy for a family history of

ovarian cancer. Familial Cancer 2001;1:14956

12. Robson M, Hensley M, Barakat R, et al. Quality

of life in women at risk for ovarian cancer who

have undergone risk-reducing oophorectomy.

Gynecol Oncol 2003;89:2817

13. Madalinska JB, van Beurden M, Bleiker EM,

et al. The impact of hormone replacement

therapy on menopausal symptoms in younger

high-risk women after prophylactic salpingooophorectomy. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3576

82

14. Lord C, Duchesne A, Pruessner JC, Lupien SJ.

Measuring indices of lifelong estrogen exposure:

self-report reliability. Climacteric 2009;12:387

94

409

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Pharmacology Alphabet AllDocumento4 páginasPharmacology Alphabet Allsflower85Ainda não há avaliações

- Pediatric G.I Disorders FinalDocumento53 páginasPediatric G.I Disorders FinalRashid Hussain0% (1)

- Yoga Therapy For Teachers D1 PDFDocumento18 páginasYoga Therapy For Teachers D1 PDFAndreea Simona CosteAinda não há avaliações

- BinatbatanDocumento5 páginasBinatbatanAmira Fatmah Quilapio89% (9)

- Community Health NursingDocumento2 páginasCommunity Health NursingAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- FootDocumento59 páginasFootAnmar Hamid Abd AlmageedAinda não há avaliações

- Pott's DiseaseDocumento8 páginasPott's DiseaseBij HilarioAinda não há avaliações

- Health Teaching Nursery BGHDocumento7 páginasHealth Teaching Nursery BGHAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- английский для психологовDocumento43 páginasанглийский для психологовTatianaAinda não há avaliações

- Informed Consent and Request For Cesarean SectionDocumento2 páginasInformed Consent and Request For Cesarean SectionkckejamanAinda não há avaliações

- Depression Among College StudentsDocumento17 páginasDepression Among College StudentsEqui TinAinda não há avaliações

- Eclampsia and Hellp SyndromeDocumento22 páginasEclampsia and Hellp SyndromeDr-Fouad ElmaadawyAinda não há avaliações

- 101 Questions About RIzalDocumento7 páginas101 Questions About RIzalAmira Fatmah Quilapio83% (24)

- Teaching Plan For Proper Breast Feeding Begh ErDocumento7 páginasTeaching Plan For Proper Breast Feeding Begh ErAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Palliative Care and Cardiovascular Disease and StrokeDocumento29 páginasPalliative Care and Cardiovascular Disease and StrokeAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- What Is It?Documento3 páginasWhat Is It?Amira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Content ServerDocumento3 páginasContent ServerAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Executive Summary Per Barangay in A Semester For CHN For FacultyDocumento5 páginasExecutive Summary Per Barangay in A Semester For CHN For FacultyAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Diarrhea CareplanDocumento6 páginasDiarrhea CareplanAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- MucusDocumento2 páginasMucusAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Gumbao, Y. (2014, August) - Slideshare. Retrieved From 7 Effects of Spanish Colonization in The Philippines: Colonization-In-The-PhilippinesDocumento1 páginaGumbao, Y. (2014, August) - Slideshare. Retrieved From 7 Effects of Spanish Colonization in The Philippines: Colonization-In-The-PhilippinesAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Natural/Artificial Family Planning (Philippines)Documento1 páginaNatural/Artificial Family Planning (Philippines)Amira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Greece:Hellenistic Civilization: ReferenceDocumento2 páginasGreece:Hellenistic Civilization: ReferenceAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Family Nursing Care PlanDocumento26 páginasFamily Nursing Care PlanAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Rosita A. Caspillan-Patrico: Career ObjectiveDocumento2 páginasRosita A. Caspillan-Patrico: Career ObjectiveAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- Saint Louis University: School of Nursing Family Nursing Assessment ToolDocumento3 páginasSaint Louis University: School of Nursing Family Nursing Assessment ToolAmira Fatmah QuilapioAinda não há avaliações

- My Top Resources (Summer 08) Adult StammeringDocumento1 páginaMy Top Resources (Summer 08) Adult StammeringSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeAinda não há avaliações

- 1246 PDFDocumento4 páginas1246 PDFPrima RiyandiAinda não há avaliações

- Annual Agreement TemplateDocumento4 páginasAnnual Agreement TemplateAngie CrutchfieldAinda não há avaliações

- V.93-3-Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Sethanne Howard and Mark CrandalllDocumento18 páginasV.93-3-Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Sethanne Howard and Mark CrandalllLori Hines ColeAinda não há avaliações

- Class Notes On Questionnaires For Pharmacology in The Gastrointestinal TractDocumento12 páginasClass Notes On Questionnaires For Pharmacology in The Gastrointestinal TractMarqxczAinda não há avaliações

- Center For Neuroacoustic Research, LLC: Some Comments About Bio-Tuning®Documento3 páginasCenter For Neuroacoustic Research, LLC: Some Comments About Bio-Tuning®oscarnineAinda não há avaliações

- Spacers Vs Nebulizers in Children With Acute AsthmaDocumento3 páginasSpacers Vs Nebulizers in Children With Acute AsthmaRichard ChandraAinda não há avaliações

- HenryDocumento21 páginasHenryEvans rizqanAinda não há avaliações

- Kasus AsmaDocumento5 páginasKasus AsmaHananun Zharfa0% (3)

- The 4th Jordanian & 3rd Pan Arab Congress in Physical Medicine, Arthritis & RehabilitationDocumento132 páginasThe 4th Jordanian & 3rd Pan Arab Congress in Physical Medicine, Arthritis & RehabilitationMedicsindex Telepin Slidecase100% (5)

- Part I سنه القمله 2016Documento20 páginasPart I سنه القمله 2016Aloah122346Ainda não há avaliações

- The Serotonin Hypothesis of Major DepressionDocumento16 páginasThe Serotonin Hypothesis of Major DepressionLorensia Fitra DwitaAinda não há avaliações

- Ilase UM PDFDocumento31 páginasIlase UM PDFVijay Prabu GAinda não há avaliações

- PL1101E - Chapter 6 NotesDocumento3 páginasPL1101E - Chapter 6 NotesMichael BAinda não há avaliações

- Tablet Splitting - To Split or Not To SplitDocumento2 páginasTablet Splitting - To Split or Not To Splitcarramrod2Ainda não há avaliações

- DrugsDocumento5 páginasDrugsVal Ian Palmes SumampongAinda não há avaliações

- 05 Abpc3303 T1Documento10 páginas05 Abpc3303 T1ڤوتري جنتايوAinda não há avaliações

- Urological Technology, Where We Will Be in Next 20 YearsDocumento8 páginasUrological Technology, Where We Will Be in Next 20 YearswanggaAinda não há avaliações

- Medicare CMS Prevention QuickReferenceChart 1Documento8 páginasMedicare CMS Prevention QuickReferenceChart 1jpmed13Ainda não há avaliações

- Psychiatric MisadventuresDocumento10 páginasPsychiatric MisadventuresRob_212Ainda não há avaliações

- Skan Respiro PlusDocumento3 páginasSkan Respiro PlusAparajitaSaha100% (1)