Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

OD Apr15 CorporateLaws V2

Enviado por

Chandra ClarkDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

OD Apr15 CorporateLaws V2

Enviado por

Chandra ClarkDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

upfront

Corporate Laws

Michael Carabash Michael James Moeller

BSc MA

BA LLB MBA

Nicholas Dunn

BSc MBA

Policy Brief:

Dental Professional Corporation Laws

in Canada

Historically, Canadian dentists delivered patient care

through various legal entities and business arrangements

be it as sole proprietors or in partnership, association or

through cost-sharing with other dentists. Dentists could

not, however, practise through a corporation due to a general prohibition; this was meant to protect the public by

making it impossible for non-dentists to control dental

practices owned by corporations. This remained the status

quo in Canada for many years until dentists, seeking the

same tax benefits enjoyed by non-professionals who owned

and operated corporations, successfully lobbied the provincial governments to enact legislation to allow them to practise through a dentistry professional corporation1 (DPC).

What follows is a brief legal overview regarding who can

own a DPC in Canada.

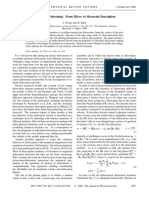

Table 1.

Laws Governing Ownership of DPCs in Canada

Province

Who Can Own Voting Shares?

2

Who Can Own Non-Voting Shares?

British Columbia

Dentists, their legal representative (e.g. executor/administer of

their estate or trustee in bankruptcy), or a holding company

whose voting shares are owned only by a dentist and whose nonvoting shares are owned by a Permitted Shareholder (see right).

A dentist or his or her spouse, child, parent, sibling or other relative, or someone who resides with the

dentist (each a Permitted Shareholder),4 or a holding company whose shares are entirely owned only by a

Permitted Shareholder or are held in trust by a Canadian resident on behalf of a Permitted Shareholder.

Alberta5

Dentists.

A dentist who also owns voting shares (a Voting Dentist) or his or her spouse, common-law partner or

child, or a trust, the beneficiaries of which are a Voting Dentists minor children.

Saskatchewan6

Dentists or their legal representative (e.g. executor/administer

of their estate or trustee in bankruptcy).

A Voting Dentist or his or her spouse, child or parent, a holding corporation whose shares are owned

by an aforementioned individual, or a trust, the beneficiaries of which are aforementioned individuals.

Manitoba7

Dentists or a Manitoba DPC.

A Voting Dentist or his or her spouse, common-law partner or child, or a holding

corporation whose shares are owned by an aforementioned individual.

Ontario8

Dentists.

A dentist or a Voting Dentists family member (i.e. spouse, child or parent) or one or more individuals,

as trustees, in trust for a Voting Dentists minor children.

Quebec9

At least one (1) dentist or a legal person, trust or other

enterprise, the voting shares of which are owned by a dentist.

At least one (1) dentist, a relative (either by direct or indirect line of descent) or spouse of a Voting

Dentist, or a legal person, trust or other enterprise whose voting shares are owned by an aforementioned

individual.

Nova Scotia10

A majority of the voting shares must be owned by a dentist.

There is no restriction on who can own non-voting shares.

New Brunswick11

A majority of the voting shares must be owned by one or

more dentists.

A dentist or a member of his or her extended family, a trust, all of the beneficiaries of which are a dentist

or a member of his or her extended family, or a holding company whose shares are owned by an

aforementioned person.

Newfoundland

and Labrador12

Dentists.

Natural persons (i.e. individual human beings), including a dentist providing dental services through the

DPC, or someone with an apparently familial or personal (i.e. non-commercial) relationship with a dentist

providing dental services through the DPC.13

Prince Edward

Island14

Dentists.

There is no restriction on who can own non-voting shares.

32

Ontario Dentist April 2015

Corporate Laws

Kester Ng

BHSc

Carlos Quionez

DMD MSc PhD FRCD(C)

Who Can Legally Own a DPC?

The laws governing ownership of DPCs are presented in

Table 1. Importantly, they differ (sometimes widely)

throughout Canada.

Policy Rationale

These laws attempt to strike a balance between two objectives. The first objective, and that which has always been

paramount, is to protect the public. That is why, although

corporations generally limit the personal liability of shareholders, a DPC will not shield a dentist personally from

claims of professional negligence. Furthermore, since only

dentists can own voting shares and act as directors and officers, they alone control the DPC.15 This authority gives

dentists unfettered professional independence when it

comes to treating patients; it also allows them to avoid (actual or perceived) conflicts of interest which could have existed had they been accountable to, or in business with,

commercially driven non-dentist investors.

The second objective of the law is to allow dentists to

defer or avoid paying taxes by practising through a DPC. In

this regard, commonly used techniques include:

leaving money in the DPC to be taxed at a lower rate, resulting in less tax being paid than if the dentist had

earned the income personally;

income-splitting by paying discretionary dividends to

family members taxed in lower income-tax brackets;

using the lifetime capital gains exemption on the sale of

shares of a DPC to avoid paying capital gains taxes (and

perhaps even multiplying the lifetime capital gains exemption by using family members);

having a shareholder borrow and repay a loan from the

DPC without paying taxes;

having a corporate will and a non-corporate will to save

on estate administration taxes; and

having an employment agreement between the DPC and

the dentist that includes $10,000 tax-free death benefits.16

Are DPC Laws Becoming Less Relevant?

Notwithstanding these worthy objectives, the laws governing who can own shares in a DPC may be becoming less

relevant. The lure of above-average returns has led sophisticated and resourceful non-dentists to effectively own and

operate a dental practice without needing to own shares in

a DPC. In Ontario, for example, this first came to public

light in the 2012 case of Smilecorp Inc. v. Pesin.17 That case

involved a contractual dispute between Smilecorp Inc.

(non-dentist) and Dr. Daniel Pesin (dentist). Of note is how

they had structured their business relationship. Pursuant

to a management agreement, Smilecorp Inc. had licensed

Dr. Pesin to provide dental services to patients at its dental

practice. The history of that practice was such that, when

a dentist left, he or she left the patient charts behind for

the next incoming dentist. Although the management

agreement stipulated that Dr. Pesin was supposed to pay

fixed amounts to Smilecorp Inc. for renting premises and

using equipment, 55 percent of Dr. Pesins billings were

going to Smilecorp Inc. In essence, Smilecorp Inc. owned

and operated the dental practice.

All of this raises important questions, such as: What does

it mean to practise dentistry? Who can legally own the assets that make up a dental practice (and specifically dental

records)? How do non-dentists get paid if dentists are prohibited from fee-splitting with them? Stay tuned. These issues will be discussed in a future Ontario Dentist article.

Michael Carabash is an Ontario dental lawyer with his own

law firm DMC Law. His websites are www.DentistLawyers.ca,

www.DentistLegalForms.com, and www.DentalPlace.ca. He

can be reached at michael@dentistlawyers.ca or 647-6809530.

Michael James Moeller holds an MA in public administration

and is a DDS candidate at the Faculty of Dentistry, University

of Toronto.

Nicholas Dunn holds an MBA and is a DDS candidate at the

Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

Kester Ng is a DDS candidate at the Faculty of Dentistry,

University of Toronto, with interests in dental economics and

dental technology.

Dr. Carlos Quionez is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of

Dentistry, University of Toronto, and Editor of Ontario Dentist.

He may be reached at cquinonez@oda.ca or 416-979-4908.

Sources page 34

April 2015 Ontario Dentist

33

Corporate Laws

Sources

1

And similarly named corporations.

Health Professions Act, R.S.B.C., 1996, c. 183, Part 4.

References to a dentist in this article shall mean an individual who is licensed to practise dentistry in that particular

province.

Note: these individuals must be related to, or reside with, a

dentist who is also a shareholder.

Health Professions Act, R.S.A., 2000, c. H-7, s. 109(1).

The Professional Corporations Act, c. P-27.1, s. 6(1).

The Dental Association Act, C.C.S.M., c. D30, s. 23.3(1).

Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991, S.O. 1991, c. 18 and

Certificates of Authorization, O. Reg. 39/02, s. 1(1)2.2.

Regulation respecting the practice of the dental profession within

a limited liability partnership or a joint-stock company, c. D-3,

r.9, Division II.

10

Dental Act, S.N.S. 1992, S. 40 and Professional Corporations

Regulations (Regulation 5), N.S. Reg. 186/93, s. 4(e).

11

An Act Respecting The New Brunswick Dental Society, Part IV, s.

21(2) and By-Law No. 22 of The New Brunswick Dental

Society.

12

Dental Act, 2008, S.N.L., c. D-6.1.

13

Newfoundland and Labrador Dental Board Advisory,

Professional Dental Corporations, point #11.

14

As per an email from Dr. Ray Wenn, Registrar of the Dental

Council of PEI, to Michael Carabash dated February 4, 2014.

15

More specifically: only dentists can vote in the board of

directors (who must also be dentists), who in turn appoint

the officers (who must also be dentists), who in turn hire or

engage others (e.g. employees, associates, suppliers, etc.) to

operate the dental practice on a day-to-day basis.

16

Note: this is a deduction to the DPC and a windfall to the

beneficiaries.

17

[2012] ONCA 853.

DCY PROFESSIONAL CORP

1/2 H AD

B&W

(REF AD # 19)

34

Ontario Dentist April 2015

Você também pode gostar

- Textbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 8, Corporate Practice of Medicine and Other Legal ImpedimentsNo EverandTextbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 8, Corporate Practice of Medicine and Other Legal ImpedimentsAinda não há avaliações

- Dentists: What You Need to Know Before Choosing a DentistNo EverandDentists: What You Need to Know Before Choosing a DentistAinda não há avaliações

- Limiting Private Equity Dentistry: A Report by Michael Davis, DDSDocumento107 páginasLimiting Private Equity Dentistry: A Report by Michael Davis, DDSDentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- Schneiderman's Settlement With Aspen Dental ManagementDocumento40 páginasSchneiderman's Settlement With Aspen Dental Managementrobertharding22100% (1)

- Waller Lansden Ad To Be Dental Management Companies Top FirmDocumento2 páginasWaller Lansden Ad To Be Dental Management Companies Top FirmDentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- DSO Organizational Chart - by Michael W. Davis, DDSDocumento1 páginaDSO Organizational Chart - by Michael W. Davis, DDSDentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- Arduin Kool Smiles Publichealth House TXDocumento24 páginasArduin Kool Smiles Publichealth House TXDentist The Menace100% (1)

- DR Jose Cazares Handout 10-15-2012Documento2 páginasDR Jose Cazares Handout 10-15-2012Dentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- List of BDA Advice SheetsDocumento6 páginasList of BDA Advice SheetsAmirah786100% (1)

- Metlife - Dental Ppo 12 15Documento3 páginasMetlife - Dental Ppo 12 15api-252555369Ainda não há avaliações

- Unitedhealthcare Dental Dental Glossary of TermsDocumento1 páginaUnitedhealthcare Dental Dental Glossary of TermsDarshilAinda não há avaliações

- Eportfolio Business AnalysisDocumento5 páginasEportfolio Business Analysisapi-546628554Ainda não há avaliações

- Laffer Associates DSO StudyDocumento17 páginasLaffer Associates DSO StudyDentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- 2015-16 Delta PPO Plan HighlightsDocumento2 páginas2015-16 Delta PPO Plan HighlightsamberarunAinda não há avaliações

- The Rapid Rise of DSOsDocumento4 páginasThe Rapid Rise of DSOsPhilip TohAinda não há avaliações

- House Hearing, 112TH Congress - The Health Care Reform Law: Its Present and Future Impact On Small Businesses and Job CreationDocumento50 páginasHouse Hearing, 112TH Congress - The Health Care Reform Law: Its Present and Future Impact On Small Businesses and Job CreationScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- DR Richard Black Handout 10-15-2012Documento4 páginasDR Richard Black Handout 10-15-2012Dentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- Delta Dental of California - Dental Ppo 12Documento2 páginasDelta Dental of California - Dental Ppo 12api-252555369Ainda não há avaliações

- Ethics in Dentistry b1Documento62 páginasEthics in Dentistry b1Jimena Chavez100% (4)

- Supporting Pupils at School With Medical Conditions: No. 276 September 2014Documento8 páginasSupporting Pupils at School With Medical Conditions: No. 276 September 2014Cornwall and Isles of Scilly LMCAinda não há avaliações

- Delta Dental PlanDocumento42 páginasDelta Dental PlanTaylorAinda não há avaliações

- The Houston Fill June 2014Documento12 páginasThe Houston Fill June 2014UTSD HoustonASDAAinda não há avaliações

- US Healthcare System Analysis v2-0Documento31 páginasUS Healthcare System Analysis v2-0Achintya KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Locum Tenens Guide - 080123Documento6 páginasLocum Tenens Guide - 080123Tom ThumbAinda não há avaliações

- CT Dental ComplaintDocumento16 páginasCT Dental ComplaintGregory Flap ColeAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocumento12 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- HHS Report - Indiana Questionable Pediatric Dental Mediciad Billing November 2014Documento25 páginasHHS Report - Indiana Questionable Pediatric Dental Mediciad Billing November 2014Dentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- Delta Dental of California - Ppo Plan 3 40 120 2000 Max 01Documento2 páginasDelta Dental of California - Ppo Plan 3 40 120 2000 Max 01api-252555369Ainda não há avaliações

- David R. Wilson President & CEO of CSHM - Small Smiles Dental Payor Letter 03-12-2014Documento2 páginasDavid R. Wilson President & CEO of CSHM - Small Smiles Dental Payor Letter 03-12-2014Dentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- The Editor'S Corner: Direct Reimbursement RevisitedDocumento2 páginasThe Editor'S Corner: Direct Reimbursement RevisitedAly OsmanAinda não há avaliações

- Pharmacists Family Planning: 5.5 Off-InvoiceDocumento2 páginasPharmacists Family Planning: 5.5 Off-InvoicepharmacydailyAinda não há avaliações

- BlueDental Copayment QF Plan BrochureDocumento4 páginasBlueDental Copayment QF Plan BrochureJoshua JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- Top 10 Regulatory Challenges in The Healthcare EnvironmentDocumento3 páginasTop 10 Regulatory Challenges in The Healthcare EnvironmentNicki BombezaAinda não há avaliações

- Our Dental Plan For Individuals and FamiliesDocumento4 páginasOur Dental Plan For Individuals and Familiesapi-41207808Ainda não há avaliações

- Dental Practitioners Amendment Bill 2019 Second Reading BriefDocumento4 páginasDental Practitioners Amendment Bill 2019 Second Reading BriefBernewsAdminAinda não há avaliações

- Questionable Billing For Medicaid Pediatric Dental Services in New York - March 2014Documento21 páginasQuestionable Billing For Medicaid Pediatric Dental Services in New York - March 2014Dentist The Menace100% (1)

- General Counsel Regulatory Compliance in Washington DC Metro Resume Mary Elizabeth LynchDocumento4 páginasGeneral Counsel Regulatory Compliance in Washington DC Metro Resume Mary Elizabeth LynchMary Elizabeth LynchAinda não há avaliações

- Dental Evolving Medical Scene: Care in The CareDocumento5 páginasDental Evolving Medical Scene: Care in The Carecarlina_the_bestAinda não há avaliações

- Marketing Plan DENTALDocumento21 páginasMarketing Plan DENTALCleriana CiorneiAinda não há avaliações

- Health Care Advocacy in The Managed Care EnvironmentDocumento45 páginasHealth Care Advocacy in The Managed Care Environmentnerd_fetishAinda não há avaliações

- OHIP Dental Coverage and Free Dental Care Ontario in 2022Documento1 páginaOHIP Dental Coverage and Free Dental Care Ontario in 2022Nishtha KumarAinda não há avaliações

- A Sample Hospital Business Plan Template - ProfitableVentureDocumento15 páginasA Sample Hospital Business Plan Template - ProfitableVentureMacmilan Trevor Jamu100% (1)

- Senor Citizens ActDocumento3 páginasSenor Citizens ActshogoyakuzaAinda não há avaliações

- James VadenDocumento4 páginasJames VadenAllison Roman RomanAinda não há avaliações

- Guide To Starting Your Dental Practice (The ADA Practical Guide Series) - American Dental Association (January 12, 2011)Documento128 páginasGuide To Starting Your Dental Practice (The ADA Practical Guide Series) - American Dental Association (January 12, 2011)Tea MetaAinda não há avaliações

- The Business of Dental PracticeDocumento5 páginasThe Business of Dental PracticeVasile FlorinAinda não há avaliações

- Guide NbdeDocumento36 páginasGuide NbdeLeShaggy DonatelloAinda não há avaliações

- 24/7 STAT Ambulance Services Diploma CourseDocumento13 páginas24/7 STAT Ambulance Services Diploma CourseMhakeeh ParkerAinda não há avaliações

- Patient Consent in DentistryDocumento5 páginasPatient Consent in DentistryJASPREETKAUR0410Ainda não há avaliações

- Practice Management Dental Insurance: A Broad Overview Laurie A. Evans, M.B.ADocumento12 páginasPractice Management Dental Insurance: A Broad Overview Laurie A. Evans, M.B.AChase ThorpeAinda não há avaliações

- CommuniK 2004.V4.1 FeesDocumento4 páginasCommuniK 2004.V4.1 FeesAlireza GoodarziAinda não há avaliações

- Generic Supplier: Now Is The Time To Join The Generic's New Generation. 308 Pharmacies Have Already JoinedDocumento4 páginasGeneric Supplier: Now Is The Time To Join The Generic's New Generation. 308 Pharmacies Have Already JoinedpharmacydailyAinda não há avaliações

- Marc Kealey's Solutions in Drug Plan ManagementDocumento18 páginasMarc Kealey's Solutions in Drug Plan ManagementMarc KealeyAinda não há avaliações

- Other Dental Consolidation TrendsDocumento1 páginaOther Dental Consolidation Trendsthomas ardaleAinda não há avaliações

- Ingle's EndodonticsDocumento19 páginasIngle's EndodonticsAndrei AntipinAinda não há avaliações

- Cue CardsDocumento8 páginasCue CardsScott Frey100% (2)

- Dental Insurance Policy-WordingDocumento10 páginasDental Insurance Policy-WordingAnthony GuoAinda não há avaliações

- 6 CDMO CDET Craig and Carl Bahr V Comfort Dental-Crag Bahr Declaration 04-04-2014Documento9 páginas6 CDMO CDET Craig and Carl Bahr V Comfort Dental-Crag Bahr Declaration 04-04-2014Dentist The MenaceAinda não há avaliações

- Real World Medicine: What Your Attending Didn't Tell You and Your Professor Didn't KnowNo EverandReal World Medicine: What Your Attending Didn't Tell You and Your Professor Didn't KnowAinda não há avaliações

- Professionalism and Ethics: A guide for dental care professionalsNo EverandProfessionalism and Ethics: A guide for dental care professionalsAinda não há avaliações

- Review of MEP Textbooks FinalDocumento10 páginasReview of MEP Textbooks FinalvickyAinda não há avaliações

- Review of MEP Textbooks FinalDocumento10 páginasReview of MEP Textbooks FinalvickyAinda não há avaliações

- Electrical Symbols CS: PVC Film, On SheetDocumento13 páginasElectrical Symbols CS: PVC Film, On SheetChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- TB08104003E Tab 1Documento152 páginasTB08104003E Tab 1priyanka236Ainda não há avaliações

- Rheem Prestige Series Package Gas Electric UnitDocumento36 páginasRheem Prestige Series Package Gas Electric UnitChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Duct FittingsDocumento31 páginasDuct FittingsSam Jose100% (7)

- Carrier - Rtu - 4 8 F C Da 0 4 A 2 A 5 - 0 A 0 A 0Documento158 páginasCarrier - Rtu - 4 8 F C Da 0 4 A 2 A 5 - 0 A 0 A 0Chandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- FDA Food - Code 2017 PDFDocumento767 páginasFDA Food - Code 2017 PDFfitri widyaAinda não há avaliações

- Milbank - U5300 O 75Documento2 páginasMilbank - U5300 O 75Chandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Commercial Product Specifications: Packaged Gas / ElectricDocumento48 páginasCommercial Product Specifications: Packaged Gas / ElectricChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Short Circuit Calculation GuideDocumento5 páginasShort Circuit Calculation Guideashok203Ainda não há avaliações

- Short Circuit Calculation GuideDocumento5 páginasShort Circuit Calculation Guideashok203Ainda não há avaliações

- Won't Crack. - . It Just Stretches: Technical DataDocumento2 páginasWon't Crack. - . It Just Stretches: Technical DataChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Electrical CodeDocumento11 páginasElectrical CodeChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- ANSYS Release Notes 190 PDFDocumento146 páginasANSYS Release Notes 190 PDFAle100% (1)

- What Is A One-Pager?: - E.M. Forster "Only Connect." - E.M. ForsterDocumento1 páginaWhat Is A One-Pager?: - E.M. Forster "Only Connect." - E.M. ForsterChandra Clark100% (1)

- IELTS Life Skills - Sample Paper A Level A1 PDFDocumento4 páginasIELTS Life Skills - Sample Paper A Level A1 PDFAnonymous QRT4uuQ100% (1)

- 50 Powerful Sales QuestionsDocumento19 páginas50 Powerful Sales QuestionsChandra Clark100% (3)

- Konsep Sistem InformasiDocumento30 páginasKonsep Sistem InformasiNijar SetiadyAinda não há avaliações

- Modeling Texture, Twinning and Hardening PDFDocumento12 páginasModeling Texture, Twinning and Hardening PDFChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Biscay: Tentative Forward ScheduleDocumento5 páginasBiscay: Tentative Forward ScheduleChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Waves 2008 11 26Documento20 páginasWaves 2008 11 26Chandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Modeling Texture, Twinning and HardeningDocumento25 páginasModeling Texture, Twinning and HardeningChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Tensor AnalysisDocumento30 páginasTensor AnalysisChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Groma Bako PhysRevLet 2000Documento4 páginasGroma Bako PhysRevLet 2000Chandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Physics and Phenomenology of Strain Hardening The FCC Case PDFDocumento103 páginasPhysics and Phenomenology of Strain Hardening The FCC Case PDFChandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Solid Mechanics 94 10Documento89 páginasSolid Mechanics 94 10landatoAinda não há avaliações

- Foundations of Tensor Analysis For Students of Physics and Engineering With An Introduction To Theory of Relativity (Nasa)Documento92 páginasFoundations of Tensor Analysis For Students of Physics and Engineering With An Introduction To Theory of Relativity (Nasa)Silver Olguín CamachoAinda não há avaliações

- ASME & IEEE Engineering Career Fair - Information Package v11Documento2 páginasASME & IEEE Engineering Career Fair - Information Package v11Chandra ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Prepaid Shipping TitleDocumento2 páginasPrepaid Shipping TitleShivam AroraAinda não há avaliações

- A Presentation On NokiaDocumento16 páginasA Presentation On Nokiajay2012jshmAinda não há avaliações

- Human Resourse Management 1Documento41 páginasHuman Resourse Management 1Shakti Awasthi100% (1)

- Supply Chain Management: Session 1: Part 1Documento8 páginasSupply Chain Management: Session 1: Part 1Safijo AlphonsAinda não há avaliações

- India's Infosys: A Case Study For Attaining Both Ethical Excellence and Business Success in A Developing CountryDocumento3 páginasIndia's Infosys: A Case Study For Attaining Both Ethical Excellence and Business Success in A Developing CountrypritamashwaniAinda não há avaliações

- Claim Form For InsuranceDocumento3 páginasClaim Form For InsuranceSai PradeepAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Ratio Analysis and Working Capital ManagementDocumento26 páginasFinancial Ratio Analysis and Working Capital Managementlucky420024Ainda não há avaliações

- Kotler & Keller (Pp. 325-349)Documento3 páginasKotler & Keller (Pp. 325-349)Lucía ZanabriaAinda não há avaliações

- Telecommunications Consultants India Ltd. (A Govt. of India Enterprise) TCIL Bhawan, Greater Kailash - 1, New Delhi - 110048Documento5 páginasTelecommunications Consultants India Ltd. (A Govt. of India Enterprise) TCIL Bhawan, Greater Kailash - 1, New Delhi - 110048Amit NishadAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment A2 - NUR AZMINA NADIA ROSLIE - 2019222588 - ENT300Documento10 páginasAssignment A2 - NUR AZMINA NADIA ROSLIE - 2019222588 - ENT300minadiaAinda não há avaliações

- Deloitte Supply Chain Analytics WorkbookDocumento0 páginaDeloitte Supply Chain Analytics Workbookneojawbreaker100% (1)

- Software PatentsDocumento13 páginasSoftware PatentsIvan Singh KhosaAinda não há avaliações

- Digests IP Law (2004)Documento10 páginasDigests IP Law (2004)Berne Guerrero100% (2)

- Ghuirani Syabellail Shahiffa/170810301082/Class X document analysisDocumento2 páginasGhuirani Syabellail Shahiffa/170810301082/Class X document analysisghuirani syabellailAinda não há avaliações

- ERP at BPCL SummaryDocumento3 páginasERP at BPCL SummaryMuneek ShahAinda não há avaliações

- 3.cinthol "Alive Is Awesome"Documento1 página3.cinthol "Alive Is Awesome"Hemant TejwaniAinda não há avaliações

- International Trade Statistics YearbookDocumento438 páginasInternational Trade Statistics YearbookJHON ALEXIS VALENCIA MENESESAinda não há avaliações

- Sage Pastel Partner Courses...Documento9 páginasSage Pastel Partner Courses...Tanaka MpofuAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 6 EntrepreneurshipDocumento13 páginasLesson 6 EntrepreneurshipRomeo BalingaoAinda não há avaliações

- TENAZAS Vs R Villegas TaxiDocumento2 páginasTENAZAS Vs R Villegas TaxiJanet Tal-udan100% (2)

- Lessons From The Enron ScandalDocumento3 páginasLessons From The Enron ScandalCharise CayabyabAinda não há avaliações

- Commodities CompaniesDocumento30 páginasCommodities Companiesabhi000_mnittAinda não há avaliações

- Customer Profitability in A Manufacturing Firm Bizzan ManufactuDocumento2 páginasCustomer Profitability in A Manufacturing Firm Bizzan Manufactutrilocksp SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Filipino Terminologies For Accountancy ADocumento27 páginasFilipino Terminologies For Accountancy ABy SommerholderAinda não há avaliações

- GAO Report On Political To Career ConversionsDocumento55 páginasGAO Report On Political To Career ConversionsJohn GrennanAinda não há avaliações

- FM S Summer Placement Report 2024Documento12 páginasFM S Summer Placement Report 2024AladeenAinda não há avaliações

- Jay Abraham - Let Them Buy Over TimeDocumento2 páginasJay Abraham - Let Them Buy Over TimeAmerican Urban English LoverAinda não há avaliações

- Emcee Script For TestimonialDocumento2 páginasEmcee Script For TestimonialJohn Cagaanan100% (3)

- Βιογραφικά ΟμιλητώνDocumento33 páginasΒιογραφικά ΟμιλητώνANDREASAinda não há avaliações

- 0 AngelList LA ReportDocumento18 páginas0 AngelList LA ReportAndrés Mora PrinceAinda não há avaliações