Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Political Parties and Foreign Policy

Enviado por

Ver Madrona Jr.Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Political Parties and Foreign Policy

Enviado por

Ver Madrona Jr.Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Political Parties and Foreign Policy: A Structuralist Approach

Author(s): Gary King

Source: Political Psychology, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Mar., 1986), pp. 83-101

Published by: International Society of Political Psychology

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3791158 .

Accessed: 03/09/2014 04:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

International Society of Political Psychology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Political Psychology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. 7, No. 1, 1986

PoliticalPsychology,

PoliticalPartiesand ForeignPolicy:A

Structuralist

Approach1

Gary King2

Thisarticleintroduces

and approachofstructural

thetheory

anthropology

and appliesitto a probleminAmerican

thisappoliticalscience.Through

and the"twopresidencies

proach,the"bipartisan

policyhypothesis"

foreign

arereformulated

andreconsidered.

Untilnowparticipants

inthe

hypothesis"

debateovereachhaveonlyrarely

builton,orevencited,theother's

research.

An additional

conventional

wisdominsupproblemis thatthewidespread

the

two

is

with

inconsistent

systematic

portof

hypotheses

scholarly

analyses.

Thispaperdemonstrates

thatthetwohypotheses

aredrawnfromthesame

structure.

Each hypothesis

modelit implies

and thetheoretical

underlying

is conceptually

andempirically

extended

to takeintoaccountthedifferences

between

leadersandmembers.

and

Then,historical

congressional

examples

statistical

thatthe

analysesofHouserollcalldataareusedto demonstrate

whilesometimes

are

members,

hypotheses,

forthecongressional

supported

decisionmaking.Conclusions

that

farmoreapplicabletoleadership

suggest

conventional

wisdombe revisedto takethesedifferences

intoaccount.

KEY WORDS: congress;foreignpolicy;leaders;politicalparties;presidency;

structural

anthropology

INTRODUCTION

is a theory

Structural

and an approachwhichhas not

anthropology

oftenbeenconsidered

or usedin politicalscienceresearch.

Thispaperinthecritical

comments

onan earlier

version

ofthisworkbyGeraldBenjamin,

'I appreciate

Leon

D. Epstein,BarbaraHinckley,

Herbert

M. Kritzer,

BeatriceL. Lewis,AnnMcCann,and

RichardM. Merelman.

I am also grateful

forthesuggestions

especially

of theeditorand

referees.

anonymous

of Politics,NewYorkUniversity,

NewYork,NewYork 10003.

2Department

83

0162-895X/86/0300-0083$05.00/1

? 1986 InternationalSocietyof Political Psychology

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

84

King

troducesstructuralism

and appliesit to a researchproblemin American

One

result

is

that

thisshouldmakeit easierforothersto use the

politics.

in

and

other

areas of politicalscience.Structural

antheory

approach

as

Levi-Strauss

and

thropology, eloquently

explicated

by

(1963,1966,1969)

others,impliesseveralassumptions.

is dividedintotwocategories:

surface

levelorconFirst,all ofculture

tentand deepstructure.

Socialscientists

neverobservemorethantheconto inferto thestructures.

tent,butwe should,itis argued,alwaysattempt

Thestructuralist

is

to

discover

structures

whichunderlie

anddetermine

goal

a variety

of surfacelevelculturalphenomena.

taketheform

ofbinary

andallmeanSecond,allstructures

oppositions,

fromthesecontrasts.

Thesymbol

doesnot

ingisderived

"red,"forexample,

mean"stop"without

itscontrast

withtheopposingsymbol"green,"

andits

associatedconcept,"go" (Leach,1970).Socialpsychologists,

forexample,

havelongidentified

socialgroupsprimarily

inrelation

to eachother(Comminsand Lockwood,1979).Politicalscientists

usuallyreferto powerrelawitha vertical

as in up:down::superordination:subortionships

metaphor:

class::"onyourwayto thetop":"falling

class:lower

dination::upper

bythe

wayside."

Structural

sometimes

andassumeor assert

anthropologists

go further

thatthesebinaryoppositions

arefundamental

characteristics

ofthehuman

it is inmind,butalthoughthisassumption

maybe of academicinterest,

unobservable

andusually

fortheanalysis

oftheresearch

herently

unnecessary

Schwartz

problem

beingconsidered.

(1981:159),forexample,

distinguishes

betweenthreelevels of universality

in dual classification.

The most

are"formal

whichincludefundamental

methaphysical

universals,"

assumptionsaboutthebinarynatureofhumanthought.

In between,

are"substantiveuniversals,

whichare observable

butdo seemto existin nature(e.g.,

hot-cold,left-right,

up-down).Finally,thereare "sociological

universals,"

whichare "thealignment

of certainmoraland socialstatesto particular

substantive

contrasts."

It is usefulto add to Schwartz's

hierarchy

political

whichI defineas thealignment

of certainpoliticalphenomena

universals,

withthemorebasicsubstantive

or social-psychological

contrasts.

that

it

is

to

allsocieties

Third,Levi-Strauss

unnecessaryexamine

argued

to

orto comparea variety

oftimeperiods discover

fundamental

structures.

Forjustas messages

whichwereceive

fromdifferent

sensescanbetransforma story),

thepastexistsonlyas a struced intoeachother(e.g.,visualizing

of the present.Thus, diachronic(overtime)and

tural transformation

(cross-cultural)

analysesaretwowaysofdoingthesamething

synchronic

characteristics

and,byso doing,uncovering

important

lookingforstructure

of humanculture.

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Parties and ForeignPolicy

85

ofthisstructural

onewhich

Byusinga version

anthropological

approach,

is unencumbered

thispaperidenbymanyofitsmetaphysical

assumptions,

tifiesand examinestwo binaryoppositions

at the levelof the political

Thegoalis notto learnabouttheformal

universals

ofthehuman

universal.3

tolearnaboutthesetwopolitical

andtheir

relabrain,butinstead

oppositions

inAmerican

isofinterest

whenwemovefrom

tionships

politics.

Deepstructure

thepoliticaluniversals

to thesocial-psychological

and substantive

universalsinorderto assistinunderstanding

and explaining

thesurface-level

relaof

concern

to

social

scientists.

tionships

In the sectionswhichfollow,two binaryoppositionsexistingin

Americanpoliticsare introduced.

betweenthetwoare first

Relationships

with

conventional

These

are

explored

however,

assumptions.

assumptions,

foundtobeinconsistent

withavailablescholarly

A better

evidence.

explanationoftherelationship

between

theoppositions

isthenpresented

alongwith

data. Finally,afterarguingthatone structural

supporting

explanation

underlies

bothoppositions,

extensions

to othersurface-level

are

phenomena

made.It turnsoutthatstructural

a usefulapproach

anthropology

provides

whichhelpsuncover

between

several

literatures

considered

relationships

rarely

butwhicharein factinexorably

combined.

related

andbeneficially

together,

As a result,newlyhypothesized

relationships

amongseveraldata setsare

derived.The data,in turn,providethefirstsystematic

evidenceof several

theoretical

important

relationships.

THE REPUBLICAN/DEMOCRATIC AND FOREIGN

POLICY/DOMESTIC POLICY BINARY OPPOSITIONS

The twobinaryoppositions

considered

hereare thedistinctions

betwocategories

tweenthepartiesandbetween

ofpublicpolicy.Considerfirst

theoppositions

theDemocratic

andtheRepublican

between

parties.Clearly

thisbinarycategorization

existsin mostpartsoftheAmerican

culture:

For

theaveragecitizen,

tobe identified

withtheDemocratic

is

to

party generally

moreliberalpositions.To be electedas a Republican

is, in general,

prefer

to takemoreconservative

issuestands.

andDemocrats

meetindifferent

national,

state,andlocal

Republicans

conventions

to choosea variety

ofpartycandidates;

fordifferent

vote

they

candidates

in different

or

caucuses

and

sit

on

different

sidesof

primaries

an aislein bothhousesof congress,

in all butone of thestatelegislatures,

3AlthoughonlyU.S. cultureis considered,the oppositionsintroducedbelow can be extended

to othernationsusing slightlymore generalterminology.

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

86

King

oflocal(city,county,

Forexamandinthousands

town,etc.)governments.

is defined

byTajfel(1982:24) as "thatpartoftheinple,"SocialIdentity"

whichderives

fromtheirknowledge

dividuals'

of... membership

self-concept

withthevalueandemotional

of

[in]a socialgroup...together

significance

For officeholders

socialidentity

to their

thatmembership."

refers

directly

partyidentification.

theRepublican/Democratic

distinction

isclearenoughtogive

Although

theboundarybetweenthetwois notwelldepartiesseparatemeanings,

fined.Ratesofsplit-ticket

and"drop-off"

"roll-off,"

voting,

1970)

(Burnham,

are high;theproportion

of theelectorate

witha politicalparty

identifying

is farfromcomplete;

ofthosewhodo identify

witha political

variable

party,

and Jacobson,

votein accordwiththeirparty(Crotty

numbers

1980);party

identification

is volatile,as areaggregate

electionreturns;

legislators

rarely

use theirpartymembership

as thesole cue forvotingdecisions(Clausen,

distinctiveness

ofaspectsofthepartiesseem

1973);andeventheideological

to havedeclined.

In sum,theboundary

between

thepartiesis crossedeasilyand often,

and can be considered

"loose"[seeLeach(1976:33-36)fora definition

of

a 'boundary'

andMerelman

for

and

of

definitions

the

con(1984) examples

is looser,theparty

ceptas it is usedhere].Buteventhoughtheboundary

distinction

is farfrombeinglost.Inthegeneral

Allen

andWilder(1975)

case,

aresimilar,

theminimal

findthatevenwhengroupbeliefs

processofin and

outgroupcategorization

is enoughto makeingroupfavoritism

(see

persist

also Billigand Tajfel,1973;Sole et al., 1975).In fact,thereis evensome

counter-intuitive

thatwhengroupshavesimilar

evidence

values,intergroup

- plausibly

discrimination

is actuallyheightened

in orderto protectgroup

distinctiveness.

boundaries

areweakening

butdo notseemindanger

So, party

of losingtheirmeaning.

to be considered

hereis thedistinction

The secondbinaryopposition

theAmerican

between

"bipartisan"

approachto foreign

policyandtheparto keep

tisanapproachto domestic

policies.It is an oftenstatedaspiration

deliberations

andpublic

policy,inbothcongressional

politicsoutofforeign

"Politicsstopsat thewater'sedge,"itis oftenwritten

discussion.

(Blissand

thatevenwhenpoliticsis part

Johnson,

1975).Thisdistinction

guarantees

itis usuallywithin

of

therhetorical

constraints

of foreign

policydecisions,

thewaycitizens

andleadersdealwith

Theboundary

between

bipartisanship.

as itoncewas,butitdoes

anddomestic

policiesmaynotbe as strong

foreign

existand is clearlyrelevant.

Thereis a largebodyofsocial-psychological

workwhichmaypartially

of theseoppositions

in termsof in group/out

explaintheexistence

group

distinctions.

Forexample,

Stein(1976)findsina review

ofempirical

literature

fromseveraldisciplines

thatinter-group

"conflict

internal

cohedoesincrease

sion undercertainconditions."Tajfel (1982) findsagreementwiththispro-

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PoliticalPartiesand ForeignPolicy

87

Freudandearlyfrustration-aggression

theorists.

from,

position

amongothers,

Otherconsequences

of in group/out

conflict

for

which

Tajfelcites

group

evidence

includetheincreased

of

oritsproevaluation

the

"positive

ingroup

ducts."

For the Democratic/Republican

opposition,the mostpronounced

and

attitudinal

distinctions

are

cognitive

likelyto occurwhenthepartiestry

to changethestatusandpowerofeachother(BrownandRoss,1982).Relevantexamplesof accentuated

outgroupdiscriminapartydistinctiveness,

and

of

levels

verbal

combat

includelegislative

tion,

heightened

inter-party

or otherleadersof thepartieshavetheir

motionsforwhichthepresident

at stake,electoral

in whichthereis an attackon the

reputation

campaigns

oftheopposition

veryexistence

group,and in debatesin whichtheparties

attackfundamental

on whichtheoppositionmakesitscase.

principles

A majorparadoxof thesetwooppositions

is thatthesamepolitical

actorswhoarepushedapartbythepartyopposition

arepulledtogether

on

Wewillseethatforparty

thesecross-pressures

leaders,

policymatters.

foreign

areexaggerated.

Oneofthecontributions

ofthispaper,therefore,

istosugforunderstanding

thisproblem.

gesta framework

OPPOSITION SIMILARITIES

thesetwooppositions

havebeentreated

oras

Traditionally,

separately

after

are

onlypartially

related;

all, they primafaciedifferent

phenomena.

Butcan theybe usefully

studiedtogether?

Arethetwobinaryoppositions

related?Andiftheyare,whatformdoestherelationship

take?Guidedby

alternative

answersto thesequestionsare nowexplored.

structuralism,

One conventional

and clearlyplausibleconnection

is thatreferred

to

Cecil

V.

Crabb

"Thetwo

by

(1957: 198),and mentioned

by manyothers:

factors

thatnormally

to favortheachievement

important

maybe expected

of bipartisan

in foreign

affairsare the nonideological

nature

cooperation

ofAmerican

incongress."

partiesandtheabsenceof strict

partydiscipline

Put differently,

whenthereis lesspartisanship

be(i.e., weakboundaries

tweentheparties),

in foreign

bipartisanship

policyis easierto achieve.The

is thatwhenthedefinitional,

and behavioral

bounhypothesis

attitudinal,

theRepublican

andtheDemocratic

darybetween

partiesbreaksdown,the

between

anddomestic

boundary

foreign

policybipartisanship

policypartisanandlesspermeable;

thatis, partisan

shipbecomestighter

politicswouldbe

lesslikelyto crosstheboundary

andinfectforeign

policydecision-making.

That ProfessorCrabb refersto the loose party boundaryby its

"nonideological"natureemphasizesthatthisculturalcode is verydifferent

fromtightly-bounded

codes, such as ideologyor religion.

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

88

King

of therelationship

thetwoopposithisstatement

between

Although

ofevidence.

tionsistheoretically

itis notsupported

reasonable,

bya variety

Considerthreecontradictory

and cross-sectional

historical

examples.

thereis considerable

evidence

thatAmerican

First,although

political

arebecoming

morepermeable,

andJacobloose,andporous(Crotty

parties

son, 1980),thereis also evidence-orat leastwidespread

expertopinionthatpartisan

theforeign

politicsareincreasingly

infecting

policyarena.As

consider

Chace(1978)as representative

of scholarly,

evidence,

journalistic,

and otheropinion:"Thekindof broadconsensus

thatobtainedduringthe

eraandwhichbecamea shibboleth

ofAmerican

postwar

foreign

policymay

no longerbe possibleshortof war."

Consistent

withthisis a dramatic

increasein suggestions

of howto

theforeign-bipartisan/domestic-partisan

Theseproposals

tighten

boundary.

includecreating

ad hoc bipartisan

to followimportant

groupsin congress

foreign

policyissues(Hamilton,1978),increasing

congressional

expertise

committees

of the president's

cabinetand

(Rourke,1977),establishing

members

of congress(Manning,1977),increasing

politically

responsible

behaviorfromAmerica's

leaders(Bax, 1977),and havingthepresident

act

inwayswhichwouldencourage

in

leaders

to

work

more

closeparty

congress

on foreign

lytogether

policyissues(FryeandRogers,1979).Ofcourse,direct

empirical

analyseswouldbe betterevidenceof thispoint,butnoneexist.4

inthishistorical

in

oftheboundary

Therefore,

example,thestrength

each of thetwobinaryoppositions

seemedto varytogetherdeloosely

finedboundaries

betweenforeign

and domestic

politicsbeingmorelikely

whentherearelooselydefined

of an inverse

parties.Theinitialhypothesis

consistent

with

conventional

is

not

relationship,

although

wisdom,

supported

in thisfirstexample.

As a secondexample,

consider

twotypesofpeoplegenerally

distinguished bysocioeconomic

levels(witheducationweighted

heavilyin thedistinction).Mostanalyseshaveshownpoliticalpartiestobe moresalienttothose

intheupperSES groups;thesegroupsaremorepolarized

lines

alongpartisan

andaremorelikelyto identify

with,andbe activein,a politicalpartythan

lowerSES groups(Ladd and Lipset,1971;Ladd withHadley,1978).

However,upperSES groupsare also morelikelyto supporta bipartisanforeign

policyandto prefer

bipartisan

foreign

policies.For example,

JohnMueller(1973:Ch. 5) identifies

a "follower

as characterizmentality"

ingpeoplewho,"takeas cuesfortheirownopinion[onwarin particular

and on foreign

affairsin general]theissuepositionof prominent

opinion

whichcouldusefully

4Thereis muchresearch

establish

thisrelationship.

One examplemight

be to content

analyzesamplesofdebateson theHouseandSenatefloorson foreign

andon

domestic

couldthenbe compared

policyissues.Levelsof conflict

and assessed.

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PoliticalPartiesand ForeignPolicy

89

thepresident.

showthat

Mueller's

leaders,"

especially

clearly

analyses

survey

of "followers."

higherSES groupshavehigherproportions

It mayseemsomewhat

thatthosein upperSES groups

contradictory

arebothmorepartisan

andmorelikelyto be "followers,"

since

particularly

theparticular

theleadermaynotbe conpathon whichtheyarefollowing

sistent

withtheir

someone

relatively

strong

partisan

predispositions.

However,

witha clearunderstanding

of thedifferences

betweenthepartiesis likely

tounderstand

whenthisboundary

shouldbe breached,

andwouldtherefore

be morelikelyto supportsuchan actionunderappropriate

circumstances.

Thus, in this second example,for those groupsin whichthe

is tight,

thebipartisan

Republican/Democratic

boundary

policy/parforeign

tisandomestic

is

also

Thisisadditional

evidence

policyboundary

tight.

against

theoriginalhypothesis;

theoppositions

do seemto varytogether.

As a finalexample,considerthedifferences

betweenmembers

and

leadersof theHouse of Representatives.

Sinceleadership

in theHouse is

it is a safeassumption

solelybasedon thepoliticalpartydistinctions,

that

the Republican/Democratic

is

fortheleadersthanthe

boundary tighter

members.

The questionthenconcerns

thesalienceof theotheropposition

to thesetwogroups;theproposition

aboveindicates

thatthisboundary

is

forthemembers,

whilethetwoprevious

tighter

thereverse.

examples

suggest

Establishingthis latter possibility-thatthe porousness of the

Republican/Democratic

boundaryvariesin the same directionas the

foreign/domestic

policyboundary-wouldprovidethe firstsystematic

evidenceof this"bipartisan

in thispaperor in

foreign

policy"hypothesis,

theliterature.

Withrollcall data fromthefirstsession(forcomparability)

of each

of fivepost-presidential

electioncongresses

thisquestioncan

(1961-1977),

be explored.Byincluding

thosevoteson whichthepresident

tooka public

andusingtherepresentative's

position(seeCongressional

voteas

Quarterly)

theunitofanalysis,

thoserollcallsinwhicha largerproportion

ofrepresentatives

votedareweighted

moreheavily.

somerepresentatives

Although

might

avoidcontroversial

examination

of rollcalls

votes,a cursory

("important")

indicates

thatthisweighting

isgenerally

inaccordwithconceptual

importance.

A potential

withtheanalysisis theclustering

ofobservations

problem

and byrollcall,possiblycausingan underestimation

by representative

of

thestandard

errors.

becausethedatasetis so large(154,709voting

However,

decisions),all of thestandarderrorsare verysmall,and a correction

is

therefore

notlikelyto changethisappreciably.5

since

decisions

Also,

many

incongress

areconcluded

without

a formalrollcall,

longbeforeor entirely

SSincethisis a pooledcross-sectional

wouldproduceinefficient

design,heteroskedasticity

and

biasedestimates.

An analysisof theresiduals,

no majorproblems.

indicates

however,

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

90

King

theremaybe a selection

bias(seeBarnowetal., 1980).Finally,

becauseonly

the firstcongressional

sessionof each presidency

was used, honeymoon

effects(Manheim,1979) may cause problems.However,becausethese

itis unlikely

effect,

analysesarenotcloselyrelatedtoa possiblehoneymoon

to greatly

altertheresults.Further

analysisof othersessionswouldnevertheless

beveryuseful.Qualifications

aside,thesedataremain

amongthebest

whichare availableat present

to analyzethesequestions.

In orderto facilitate

all equationsexplaintheprobability

comparison,

and all controlforthe effectsof region

of votingwiththe president,

"In"(i.e.,president's)

and"Out"(i.e.,opposileadership,

party

(north/south),

arenot

tion)partymembership

(Republican/Democratic

partydifferences

to In/Outpartydifferences),

issuearea,presiverystrongin comparison

ofthisprocedure

is totakeintoacdent,andtimeperiod.Theconsequence

rivalhypotheses

countseveral

aboutvoting

withthepresident.6

The

plausible

modelis a logisticanalysisof tabulardata. In partymembers

areexpected

tosupport

morethanOutpartymembers.

In thecaseofbiparthepresident

tisandecision-making,

theIn/Outpartysplitin supportof thepresident

is

to be greateron domesticthanon foreign

hypothesized

policydecisions.

In orderto allowforthepossibility

thatthereis morevariation

within

thebroadcategories

ofdomestic

andforeign

there

policythanbetween

them,

are threeforeign

policyand fourdomestic

roll

of

calls.

policycategories

Thiscodingofpolicycategories

isconsistent

withvariedresults

from

separatestudies

lyconducted

domestic

[seeKessel(1974)andClausen(1973)forsimilar

codingsand Hughes(1978)forsimilarforeign

policycodings)].

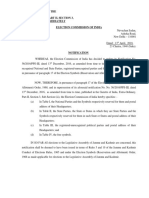

Thefigures

arepresented

withall years(1961-1977)

combined

because

indicated

that

similar

hold

preliminary

analyses

relationships

generally up

overtimeandbecauseofthebenefits

ofsavingspaceandreducing

complexthepredicted

valuesof a logisticequationexplaining

ity.Figure1 presents

theprobability

ofthepartyleadervoting

withthepresident.'

Estimated

probabilities

fortheIn and Outpartiesacrossthesevenpolicyareasappearin

theFigure.The largerthedifference

between

theIn and Out partiesfora

area

vertical

distance

between

thelinesinthefigure),

particular

policy

(the

thestronger

are thepartyboundariesforthatpolicyarea.

The firstthingto noticeaboutFigure1 is that,as expected,

In party

members

oftheHouseofRepresentatives

(thetoplineinthefigure)

support

thepossibility

reduces

thatleaders

andmembers

controls

thesestatistical

substantially

6Including

rather

thandesign.

do so bycoincidence

whovotewiththepresident

Forthisanalysis,

of eachpartyaretheonlyrealleadersin congress.

7Theformalleadership

Ifthetopthree

whovotesisconsidered.

leaders

leaderfrom

eachparty

ranking

onlythehighest

votesonlyinthecaseofa tie),theroll

theSpeaker,whobytradition

do notvote(excluding

call is excludedfromtheanalysis.

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

91

Political Parties and ForeignPolicy

thepresident

farmoreoftenthanOutpartymembers

(thelowerline).But

which

couldplausibly

also

that

for

defense

indicates

Figure1

except

policy

of

than

a

more

a

domestic

be explained

Vietnam

policy

by

becoming

foreign

issue(which,incidentally,

supportsthefirstexample,above)-thereis a

In foreign

inleadership

forthepresident:

difference

support

policy,

striking

ofan In partycongressional

leadersupporting

thepresident

theprobability

is about25percentage

leaders(excluding

defense).

pointsmorethanOutparty

forthepresident

isabouttwice

thissplitinparty

However,

leadership

support

leaderas greatinthefourdomestic

Thus,amongtheparty

policycategories.

a verytightboundary,

betweenpoliticsin

ship,thereis a cleardifference,

foreignpolicy-whichtendsto be bipartisan-andpoliticsin domestic

Thisis witnessed

bythecleardistinction

policy- whichtendstobe partisan.

betweentheleftand rightsidesof thefigure.

In a parallelpresentation,

thesamedata,butforthe

Figure2 displays

thetwofigures

between

of theHouse. The difference

generalmembership

thereis considerably

lessdistinction

is dramatic:

(i.e.,

Amongthemembers

betweenforeignand domesticpolicydecision-making

looserboundaries)

still

Thereis, however,

theleftandrightsidesofthefigure).

(i.e., between

PROBABILITY

OF THE

PARTY

.90

WITHTHE

.80

LEADER

VOTING

PRESIDENT

.70

.60

IN PARTY

A

/

OUTPARTY

.50

.40

.30

For- For- DeSo- Gov't EnAgrieign eign fense cial Mgt ergy culture

Trade Aid

Welfare

POLICY AREA

forthepresident.

Source:Percentsupport

Mg. 1. In and Outpartyleadership

Note:

fromthePM,MI logitmodel.d.f. = 48, G2 = 10667.35.

agescomputed

Forall figures,

modelabbreviations

areas follows:

Issueorpolicyarea(I), Presi-

dent(P), Party

Leader's

position

(L), andparty

membership

(M).

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

King

92

aid decisionsthere

For example,on votingforforeign

somerelationship.

of a

in theprobability

is on theaverageno In and Out partydifference

in

the

In

with

the

government

representative

voting

president. contrast,

In partymembers

are abouttenpointsmorelikely

management

category,

thedifButalthough

thanOut partymembers.

to votewiththepresident

nowhere

near

as tight

the

boundaries

are

ferences

areinthecorrect

direction,

in Figure1.

as forthepartyleadersrepresented

Thusin thisexample,as in theprevious

two,thetwobinaryopposiWhentheRepublican/Democratic

is

tionstendto varytogether:

boundary

tight(as forthe partyleaders),the Foreign-Bipartisan/Domestic-Partisan

is also tight.Whentherearesomewhat

weakerpartydistinctions

boundary

therearealso looserdistinctions

between

(as forHousemembers),

typesof

orpartisan)

indifferent

ordomestic).

(bipartisan

policyareas(foreign

politics

It is clearthatan alternative

is needed.

explanation

TWO BINARY OPPOSITIONS-ONE

UNDERLYING STRUCTURE

Theinitialproposition

wasthatthetwocodesvariedinversely:

When

the boundarybetweenone was tightthe othershouldbe loose. This

.79

PROBABILITY

IN PARTY

MEMBER

.60

/

OF A

REPRESENTATIVE

.50

VOTING

WITH

THE

PRESIDENT

.40

OUT PARTY

MEMBER

.30

.20

.1o

I

Foreign

Trade

I .

For- DeSo- Gov't En- Agrieign fense cial Mgt ergy culture

Aid

Welfare

POLICY AREAS

Fig. 2. In and Out partyrepresentatives'

supportforthePresident.Source: Percentages computedfromthePLM,MI logitmodel. d.f. = 108, G2 = 4982.28; MI component: d.f. = 6, G2 = 315.17.

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Parties and ForeignPolicy

93

- although

- wassupnotextensively

exploredintheliterature

proposition

and

conventional

science

wisdom.

It

political

portedbyplausibleargument

in

known

in

fact"

and

as

a

"well

as

comments

articles

many

scholarly

appears

fromthreeexamples

evidence

demonstrated

textbooks.

However,empirical

theboundaries

between

thecodes

notthecase.Rather,

thatthiswasprobably

was

the

other

code

was

loose

one

code

when

seemedtovarytogether

loose,

with

no

but

ofa relationship

as well.Thisleavesuswithevidence

explanation.

to recognize

thatimitis important

In orderto derivean explanation,

is

thusfaris thateachof thesebinaryoppositions

plicitin thediscussion

a signalormetaphoric

symbolfortheother.It wasimpliedthattheopposior apartor thatone causedtheother.An alternative

tionsvariedtogether

is thatthetwo

tobe offered,

andthebasisfortheexplanation

formulation,

toeachother.In other

aremetonymic;

words,

theyarecontiguous

oppositions

is a structural

one binaryopposition

transformation

oftheother:Onefununderlies

bothdistinctions.

damentalstructure

bebasisforthesetwocodesis thedistinction

Thecommonstructural

"same"and"different;"

tween"we"and"they"

between

(or,moregenerally,

to thesurfacetheformer

areusedbecausetheyhavemoredirectrelevance

ofinterest).

Theconceptof"we"doesnothavemeaning

levelrelationships

anddefined.

untiltheopposingconceptof"they"is contrasted

Thisdistincin manyareas: For example,David Truman's"Wave

tionis recognized

is basedon thisdistinction:

Theory"ofinterest

"Organizagroupformation

hewrites

tionbegetscounterorganization,"

(Truman,1956).Impliedis that

thecounterorganization

without

theoriginalorganization,

wouldnothave

itself

thefirst

defined

as a group(as "we")without

(andidengroupforming

themselves

as

"we"

and

else

as

"they").

tifying

everyone

canbe appliedtoMiddleEastern

ConcomiThesameprinciple

politics:

tantwiththesharpincreasein immigration

of Jewsto Palestineearlierin

was

thiscentury

andtheirself-identification

as "we,"and othersas "they,"

of theArabslivingin thearea as "we,"and theJewsas

theself-definition

at linguistic

distinctiveness

also increased

"they"(Safran,1978); efforts

not exist

for

could

this

example,

period(Seckback,1974).War,

during

without

thewe/they

opposition.

whichdo notderive

Thereare,of course,manypoliticalphenomena

froma we/they

as whenpoliticalactionis basedon a senseof

distinction,

or consensus.In thefirstpresidential

forexample,

elections,

community

thatthepoliticalpartyto whomthespeaker

emphasized

politicalrhetoric

or in factactuallywas,thewillof thenation.

belongedbestrepresented,

JohnAnderson's1976"NationalUnityParty,"and Reagan's1984appeal

fora "newpatriotism"

are morerecentexamples.

The current

can be reformulated

Democratic/Republican

opposition

in this manner as "my party/otherparty," and the Foreignbinary opposition can also be viewed as

Bipartisan/Domestic-Partisan

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

94

King

Insteadofthedivision

thewe/they

distinction.

beingbetween

parredefining

ties,it is betweentheU.S. and theworld(or betweentheU.S. and parts

thesetwooppositions

arereallysurfaceoftheworld).Fromthisperspective,

of thesamewe/they

or transformations

level(or content)manifestations

structural

opposition.

- thebinary

- and

Thusfara relationship

varying

together

oppositions

- a structural

- havebeenassembled.

an underlying

But

identity

explanation

interest

is ofacademicandexploratory

(andremains

although

deepstructure

as presently

an inference),

itis thepoliticalcontent

conceptualized

entirely

to politicalscientists.

Thesefindings

must

thatis moreoftenof interest

In

substantive

therefore

be relatedbackto theoriginal

sum,

why

problem.8

of interest?

is thisstructural

relationship

The basicobservation

is thatstrongandclearlydefined

politicalpartiesleadtothebipartisan

offoreign

operation

policyandtheusualpartisan

ofdomestic

follows

With"strong"

operation

policy.Theexplanation

directly:

thereis thepossibility

of

parties,thatis witha strong

we/they

opposition,

an agreement

betweenthepartyleaders;theleaderscan speakmoreconfortheirpartymembers

and can makecompromises

withopposifidently

tionpartyleadersmoreeasily.9

Furthermore,

(i.e.,interparty

bipartisanship

is mostlikelywhentheissuedefines

thewe/they

as

agreement)

opposition

theUnitedStatesversusothernations;ofcourse,bipartisanship

is possible

in otherissueareas,butitseemslikely

to be mostfrequent

in foreign

policy.

distinction

leads to

Thus,a strong,well-defined

Republican/Democratic

clearer

boundaries

between

anddomestic

foreign

policybipartisanship

policy

Based on systematic

redefines

the

evidence,thiseffectively

partisanship.

bipartisan

foreign

policyhypothesis.

STRUCTURAL EXTENSIONS

Thereare numerous(surface-level)

manifestations

of thestructural

wavetheory

ofinterest

we/they

binary

opposition.

ExamplesfromTruman's

and fromMiddleEasternpoliticshavealreadybeenprogroupformation

vided.Widevarieties

ofotherapplications

couldbeexplicated

inconsiderable

of socialgroup

detail.For a fewshortexamples,consider:Explanations

forthepsychological

andsociological

ofthe

solidarity;

arguments

necessity

8L6vi-Strauss

havebeensatisfied

I concentrate

on using

here,butforpresent

might

purposes,

structural

to understand

thesurface-level

of primary

interest

to

anthropology

phenomena

politicalscientists.

forthosecircumstances

wheninter-group

doesnotleadto ingroup

90n evidence

competition

cohesion.See Tajfel(1982:16);RabbieanddeBrey

(1971);RabbieandWilkens

(1971);Rabbie and Huygen(1974);Rabbieet al. (1974);and Horwitzand Rabbie(1982).

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PoliticalPartiesand ForeignPolicy

95

andracism;exploraoritssurrogates;

ethnocentricity

understanding

family

of

the

ofthe

ofthenation-state;

tionsoftheorigins

explanations development

the

for

which

some

creates;

certain

advertising

products

political

party; loyalty

tocertain

teams(whicharenotcoincidently

theappealofsportsandloyalty

andcities);andthetremendous

namedforlocalproducts

appealoftheOlym"The

U.S. versesThe

events

as

titles

some

network

television

pics (one

the

be

extended.

The

list

could

Instead, approachsuggested

bythis

World").

onepoliticalissue

to examining

methodinthispaperis limited

structuralist

relatedto theoriginaltwobinaryoppositions.

ofthewe/they

surfacelevelmanifestation

Another

binaryopposition

in theconand thepresidency

between

is theinstitutional

congress

rivalry

ductofforeign

in

that

policy.Thisbinary

foreign

policy

opposition

suggests

to supportthe

aremorelikelyto crosstheopposition

boundary

legislators

thecongress/presidency

In domestic

boundary

policy,however,

president.

shoulddrop.

becomesmoresalientand supportforthepresident

on thelevelof

Thusfar,party,policy,and institutional

oppositions

All threeseemto be relatedto the

havebeenidentified.

politicaluniversals

someofthe

structure.

Crabb(1957:7) describes

samesocial-psychological

betweenthese:

distinctions

- relations

andrelations

theexWhilethetwoproblems

between

theparties

between

- areintimately

canresult

ecutive

andlegislative

branches

connected,

onlyconfusion

fromregarding

thetwo

themas identical

problems.

Harmony

mayprevailbetween

branches

ofgovernment

concerned

withforeign

butthisfactalonewillnot

affairs;

in theforeign

guarantee

bipartisan

co-operation

policyrealm.(Crabb,1957:7)

The questionof boundaries

between

theHouseand thepresidency

is

addressed

he

byPolsby(1968).An institutionalized

explicitly

organization

thatis to say,differentiated

well-bounded,

arguesis, interalia, "relatively

An increaseinthisboundedness

fromitsenvironment."

or institutionalizationis clearlyobservedbya decreaseintheturnover

of members,

increase

in theaveragelengthof service,

increasein theseniority

of successful

canin and

didatesforSpeaker,and sharpdeclineof lateralcareermovement,

outoftheHouseand,insomenotablecases,alsoinandoutofthespeakerdistinction

between

ship.Thus,therehasbeen,overtime,a clearerwe/they

and

the

congress

presidency.

Fromtheconclusion

abovethatthestrength

of theboundaries

vary

in thesamedirection,

thestronger

between

and itsenboundary

congress

and thusbetweencongress

and thepresidency,

shouldlead to

vironment,

an increased

of

between

the

two

of governbranches

possibility agreement

in

this

should

be

most

affairs

wherethe

ment; agreement

apparent foreign

is

reformulated

to

for

incentive

we/theyopposition

provide

congresconsensus.

sional/presidential

It shouldbe notedthatthecongress/presidency

distinction

is an institutionalopposition,whereastheothersare cognitiveor social oppositions.The

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

King

96

onthebasisofcognitive

originated

probably

congress/presidency

opposition

once

to thefounders,

butthisinstitutional

relevant

distinction,

oppositions

thewe/they

and exaggerated

in place,probablyencouraged

opcognitive

blurswhenconsidering

politicalpartieswhich,

position.The distinction

havebeeninsitugovernment,

althoughnevera formalpartof American

tionalizedsinceitsinception.

is clearly

thecongressional/presidential

becoming

boundary

Although

inforeign

from

whether

theliterature

tighter

(Polsby,1968),itisnotapparent

increasein agreement

between

affairsthishas resultedin the predicted

Whatisoften

ofcongress

andthepresident.

calledthetwopresidenmembers

ciesliterature

byWildavsky

(1966)]is farfromcon[basedonthehypothesis

sensuson eitherthe levelor the trendof congressional

supportforthe

versusdomestic

In fact,evengiventheplausion foreign

affairs.

president

ble case Wildavsky

makesforit, thereexistsno satisfactory

systematic

workinthetwo

thatpublished

evidenceofthishypothesis.

(It is interesting

and bipartisan

foreign

rarelyciteeachother

policyliteratures

presidencies

orbuildon eachother's

work.Thestructuralist

herehelps

approach

employed

makethisconnection.)

and

Forexample,

LeLoupandShull(1979)updateWildavsky's

analysis

find

for

his

thesis

that

the

to

for

appear

support

congressional

support

presidentis greater

on foreign

thanon domestic

affairs

butfindthattherelationinrecent

withthisanalysis,

andwith

years.Theproblem

shipis notas strong

is

that

their

measure

of

is

no

Wildavsky's

longer

originalarticle,

support

becauseof whatCQ callsits

beingcompiledby Congressional

Quarterly

"dubiousquality."Lee Sigelman(1979)usesa different

measureand finds

noappreciable

and

Forpotential

difference

between

domestic

foreign

support.

with

the

and

see

Shull

problems

Sigelmanstudy LeLoup

(1980).

In orderto providea moresystematic

examination

of thisquestion,

thedata analyzedin Figures1 and 2 can be examinedfurther.

Againdata

arepresented

forthemembers

andthepartyleaders.Thehypothesis

is that

as a consequence

of thetightboundaries

betweencongress

and thepresiwillsupport

thepresident

moreon foreign

dent,boththeleadersandmembers

thanondomestic

affairs

rollcalls.Furthermore,

from

theeffects

ofstratificationobserved

shouldbe stronger

above,therelationship

amongtheleaders

thanthefollowers.

valuesof a logisticequationexplaining

the

Figure3 reports

predicted

oftheparty

leadervoting

withthepresident

foreachoftheseven

probability

that,withdefense

policyareas.Itsuggests

policyas a possible

exception

again,

decisionson foreign

affairsare farmorelikelyto be supportive

leadership

on domestic

affairs.

Thedifference

ofthepresident

thanaredecisions

is also

Theprobability

with

ofa congressional

leaderofeither

striking:

party

voting

the presidentapproachescertaintyforforeignaffairsbut remainsa full25

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PoliticalPartiesand ForeignPolicy

97

1.00

PROBABILITY .90

OF THE

PARTY

LEADER

VOTING

WITH THE

PRESIDENT

.80

.70

.60

For- For- DeSo- Gov't En- Agrieign eign fense cial Mgt ergy culture

Trade Aid

Welfare

POLICY AREA

fromthe

forthePresident.

Source:Percentages

computed

Fig.3. Partyleadership

support

PM,I logitmodel. d.f. = 9, G2 = 11940.89; PM component:d.f. = 9, G2 = 54313.98.

Supportforthepresipolicydecisions.

percentage

pointslowerfordomestic

inforeign

tradethanforeign

dentis somewhat

aid,andthereis some

higher

variationin supportamongthedomesticpolicies,but,againexceptfor

and domestic

is betweenforeign

distinction

policies.

defense,theprimary

thesis

Thus,amongpartyleadersin theHouse,thetwopresidencies

ofleaderWithforeign

is wellsupported:

probability

policycomesa greater

withtheincumbent

president.

shipagreement

ofthe

a parallelanalysisforthegeneralmembership

Figure4 provides

of a representative

House. As is apparent,

theprobability

votingwiththe

affairs.

between

anddomestic

is notsubstantially

different

foreign

president

is in a foreign

In fact,theweakestsupportforthepresident

policyarea

withtheargument

thatthosehigher

(foreign

aid). Whilethisis consistent

tendto supporttighter

in American's

hierarchies

stratification

boundaries,

it does notsupportthepresent

argument.

frompreviousexamplesthat

To review:It was initially

hypothesized

between

"we"and "they"shouldresultin

moreclearlydefinedboundaries

of we/they

moreintra-group

cohesionandthusa greater

agreepossibility

menton important

this

case

issues.

For

executive-legislative

(in

foreign

policy)

thisgeneralization

but

remains

accurateforthepartyleadership

relations,

notforthegeneralmembership.

the

Therefore,

although partyleadership

thusfar,themembers

can

fitnicely

intothestructural

explanation

presented

be

considered

an

only

exception.

A possibleexplanation

of thisexception

can be foundin a closerexin

It

of historical

amination

changes congress. has alreadybeenobserved

thatcongress

has steadily

becomemoreboundedfromthepresidency

(and

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98

King

.80

.70

.60

PROBABILITY

OF A

REPRESENTATIVE

VOTING WITH

.50

THE

PRESIDENT

.4o_

.30

.20

So- Gov't En- AgriFor- For- Deeign eign fense cial Mgt ergy culture

WelTrade Aid

fare

POLICY AREA

Source:Percentages

Fig. 4. Partymembership

supportforthePresident.

computed

fromthePLM,I logitmodel.d.f. = 114,G = 5297.41;PLM component:

d.f. = 19,

G = 39665.76.

in

Thistrendcan easilybe seenas resulting,

therestof itsenvironment).

inthelegislative

involvement

(Davidpart,froma greater

presidential

process

son and Oleszek,1981:36-9;Wayne,1978:8, passim).In otherwords,as

a methodof protecting

has set

itselffrompresidential

hegemony,

congress

decentralization.

which

institutional

decision-making

emphasize

procedures

up

ifcongress

One indication

of theprobableconsequence

had becomemore

centralized

is thegreater

for

the

president

amongtheformalparty

support

Centralization

would

the

leaders

more

whichin

influence,

give

leadership:

would

The

dominance.

current

turn,

probably

promote

presidential

"strategy"

- oneofdivideorbe conquered

- preserves

ofdecentralization

congressional

BarbaraHinckley

illustraseveral

(1978:206)provides

prerogative.

important

tionsof thisargument:

Theseniority

creates

a committee

ofparty

leadersinsystem

leadership

independent

thepresident.

incommittees

andsubcommittees

cangenerate

cluding

Specialization

to presidential

influence.

Midterm

elections

counter

subgovernments

impenetrable

ofPresidential

theeffect

coattails

from

thepreceding

backafter

two

election,

cutting

termthefirstfullstrength

of a president's

yearsof a four-year

partisan

support.

Whilethe institutions

and groupsmentioned

above becomevery

cohesivein thefaceof stronger

boundaries

what

unitesthecountry

(e.g.,

thana goodwar?),clearer

inthewe/they

better

boundaries

distinction

have,

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PoliticalPartiesand ForeignPolicy

99

cohesion.Always

in thecongressional

intra-group

example,discouraged

the

took

of

and

its

(whether

logicalapproach

congress

jealous

power position,

inor not)ofdecentralizing

intended

and,as a result,reducing

presidential

whocaninfluence

Thatis, "becausetherearefewermembers

fluence.

large

must

ofpointsat whichpresidents

thenumber

oftheircolleagues,

numbers

more."

is...that

much

the

influence

to

(Davis, 1979).

congress

attempt

inthiscase,is lesspresidential

theresultofstronger

boundaries,

Therefore,

in congressand lessinstitutional

influence

agreement.

CONCLUSIONS

intheform

In thelanguageofstructural

deepstructure,

anthropology,

to

of thewe/they

seems

have

been

identified.

Several

binaryopposition,

havebeen

manifestations

rather

thanstructural)

surface-level

(i.e., content

elaborate

ofLevi-Strauss'

Reminiscent

andexplained.

contingency

explored

intermsofall possiblecombinations

structure

tablesexpressing

underlying

also foundthatthetranslation

thisanalysis

ofcultural

processfrom

artifact,

has notbeenuniform.

to surface-level

structure

phenomena

Profoundhistorical

of, politicalparties,

changesin, and dynamics

and

verses

relations,

bipartisanship partisanship,

congressional-presidential

More

framework.

within

this

understood

all

be

area

can

effects

usefully

policy

havebeenestablished:

thefollowing

structural

analogiesbetween

formally,

policy:domesticpolicy::conwe:they::Republican:Democrat::foreign

between

Whentheboundaries

anyofthesepairsis strong,

gress:president.

betweenanyotherpairis also likelyto be strong.

theboundary

Thisapproachhas also helpedto connectand relatetwoliteratures

with

literatures

and

the

the"twopresidencies"

"bipartisan

foreign

policy"

andstructural

butwithnumerous

substantive

fewcross-references

currently

ofconsidering

the

some

of

benefits

Thispaperhasdemonstrated

relationships.

thesetwoliteratures

simultaneously.

ofandsystematic

Theapproachhasalsoledtotheoretical

justification

and

thetwopresidencies

evidenceforboththebipartisan

policy

foreign

andfifty

thousand

ofmorethanonehundred

Ananalysis

voting

hypotheses.

bothhypotheses,

terms

sometimes

decisionsfromfivepresidential

supports

is substantially

buttherelationship

amongtheleadersthanamong

stronger

of theU.S. House of Representatives.

the members

Thus,conventional

visiblegroup-is more

wisdom- whichmaybe basedmoreon thishighly

leadersand

areappliedto congressional

plausiblewhenseparatehypotheses

members.

theuniquepositionoftheparty

Theanalysishasalso helpedtoclarify

- cross-pressured

incongress

oftwostructural

at theintersection

leadership

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

100

King

The congress/presidency

theleadersto

oppositions.

opposition

encourages

sidewithcongress

andagainstthepresident.

It suggests

thattheleadersresist

at persuasion

and protectcongressional

presidential

attempts

prerogative.

However,theRepublican/Democratic

opposition

pushestheseleadersin a

different

direction.

Forindecentralized

suchas theU.S. conorganizations

is power;so, to acquireinformation

and perhapsa

gress,information

endorsement

of favoredpolicyobjectives,

theleadershaveinpresidential

centives

to associatewiththepresident.

Thisassociationgivestheleaders

- whichresults

moreofa presidential

thanothermembers

infar

perspective

the

for

the

leaders

than

the

membergreater

support

president

by

by general

forcogniship.Beinga leaderin theU.S. House,then,has consequences

tionthatbeinga member

doesnothave.Theresultforthepartyleadership

is a difficult

positionand an ambiguousrole.

REFERENCES

and attribution

of beliefsimilariAllen,V. L., and Wilder,D. A. (1979). Groupcategorization

ty. Small Group Behavior 110: 73-80.

Barnow,B. S., Cain, G. G., and Goldberger,A. S. (1980). Issues in theanalysisof selectivity

E. W. and Farkas,

bias. Evaluation StudiesReviewAnnual: Volume5. Stromsdofer,

G. (eds.), Sage Publications,BeverlyHills.

relationsin foreignpolicy: New partisanshipor new

Bax, F. R. (1977). Legislative-executive

competition?Orbis. 20 (Winter):881-904.

in intergroupbehavior

Billig,M., and Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorizationand similarity

Eur. J. Social Psychol. 3: 27-52.

Brown, R. J., and Ross, G. F. (1982). The battlefor acceptance:An investigationinto the

behavior.In Tajfel,H. (ed.), Social Identityand Intergroup

Reladynamicsof intergroup

tions,CambridgeUniv. Press, Cambridge.

Burnham,W. D. (1970). CriticalElectionsand TheMainspringof AmericanPolitics,Norton,

New York.

Bliss, H., and Johnson,M. G. (1975). Beyond The Water'sEdge: America'sForeignPolicies,

Lippincott,Philadelphia.

Chace, J. (1978). Is a foreignpolicyconsensuspossible? ForeignAffairs(Fall): 1-16.

Decide: A PolicyFocus, St. Martin'sPress,New York.

Clausen,A. R. (1973). How Congressmen

An experimental

Commins,B., and Lockwood,J.(1979).Social comparisonand socialinequality:

investigationin intergroupbehavior.Brit. J. Soc. Psychol. 9: 281-89.

Crabb, C. V. (1957). BipartisanForeignPolicy: Myth Or Reality,Row, Peterson,and Co.

Evanston,Ill.

Crotty,W. J.,and Jacobson,G. C. (1980). AmericanPartiesinDecline,Little,Brown,Boston.

influenceon CapitolHill.

Davis, E. L. (1979). Legislativereformand thedeclineof presidential

Brit. J. Pol. Sci. 9 (October): 456-479.

Davison, R. H., and Oleszek, W. J. (1981). Congress and Its Members, Congressional

Quarterly:Washington,D.C.

Frye,A., and Rogers,W. D. (1979). Linkagesbeginat home.ForeignPolicy35 (Summer):49-67.

Gamst, F. C., and Norbeck,E. (1976). Ideas of Culture:Sources and Uses, Holt, Rinehart,

and Winston,New York.

Hamilton,L. H. (1978). Makingtheseparationof powerswork.ForeignAffairs57,1(Fall): 17-39.

Hinckley,B. (1978). Stabilityand Change in Congress,Harper & Row, New York.

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Parties and ForeignPolicy

101

in theintergroup

and membership

Horwitz,M., and Rabbie, J. M. (1982). Individuality

system.

In H. Tajfel(ed.), Social Identityand Intergroup

Relations,CambridgeUniversity

Press,

Cambridge.

Hughes, B. (1978). Domestic Contextof AmericanForeign Policy, W. H. Freeman, San

Francisco.

Kessel, J. (1974). The parametersof presidentialpolitics.Soc. Sci. Quart. (June): 8-24.

Ladd, E. C., withHadley, C. D. (1978). Transformations

of AmericanPolitics,Norton,New

York.

Ladd, E. C., Jr.,and Lipsett,S. M. (1971). College Generations:Fromthe 1930sto the 1960s.

Public Interest,25: 105-109.

Leach, E. (1970). Levi-Strauss,London: Collins.

Leach, E. (1976). Cultureand Communication,MIT Press, Cambridge,Mass.

LeLoup, L., and Shull,S. A. (1979). Congressversustheexcutive:The two presidenciesreconsidered.Soc. Sci. Quart. 59,41 (March): 704-719.

LeLoup, L., and Shull, S. A. (1980). A commenton Sigelman.J. Politics 42.

L6vi-Strauss,C. (1963). StructuralAnthropology,Doubleday, Garden City.

L6vi-Strauss,C. (1966). The Savage Mind, Universityof Chicago Press, Chicago.

L6vi-Strauss,C. (1969). The Raw and The Cooked, Harper & Row, New York.

Manheim,J. B. (1979). The honeymoon'sover: The newsconferenceand thedevelopmentof

presidentialstyle.J. Politics (February):55-74.

affairs:Threeproposals.Foreign

and intermestic

Manning,B. (1977). The congress,theexecutive,

Affairs55,2 (January):306-324.

Merelman,R. M. (1984). MakingSomething

of Ourselves:On Cultureand PoliticsIn The United

States, Universityof CaliforniaPress, Berkeleyand Los Angeles.

Mueller,J. E. (1973). War, Presidents,and Public Opinion, Wiley,New York.

Am. Polit.

of theU.S. House of Representatives.

Polsby,N. W. (1968). The institutionalization

Sci. Rev. (March): 144-168.

Rabbie, J. M., Benoist,F., Oosterbaan,H., and Visser,L. (1974). Differentalpowerand efinteractionon intragroupand

fectsof expectedcompetitiveand cooperativeintergroup

outgroupattitudes.J. PersonalitySoc. Psychol. 30: 46-56.

Rabbie, J. M., and deBrey,J. H. C. (1971). The anticipationof intergroupcooperationand

competitionunderprivateand public conditions.Int. J. Group Tensions 1: 230-251.

and theireffectson attitudes

Rabbie, J. M., and Huygen,K. (1974). Internaldisagreements

toward in- and outgroups.Int. J. Group Tensions4: 222-246.

Rabbie, J. M., and Wilkens,G. (1971). IntergroupCompetitionand Its Effecton Intragroup

and IntergroupRelations.Eur. J. Social Psychol. 1:215-234.

Rourke, J. T. (1977). Congressand the Cold War. WorldAffairs139 (Spring): 259-277.

Safran,N. (1978). Israel TheEmbattledAlly,The BelknapPressof HarvardUniv. Press,Cambridge.

and The Sociologyof

Schwartz,B. (1981). VerticalClassification:A StudyIn Structuralism

Knowledge,The Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Seckbach, F. (1974). Attitudesand opinionsof Israeliteachersand studentsabout aspectsof

modernHebrew. Int. J. Sociologi. Language 1: 105-124.

Sigelman,L. (1979). A reassessmentof the two presidenciesthesis.J. Politics 41: 1195-1205.

and helping:Threefieldexperiments

the

Sole, K. et al. (1975). Opinionsimilarity

investigating

bases of promotivetension.J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 11: 1-13.

Stein,A. A. (1976). Conflictand cohesion:A reviewof the literature.J. ConflictResolution

20: 143-172.

Press,Paris.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social Identityand IntergroupRelations,CambridgeUniversity

Truman, D. (1956). The GovernmentalProcess, Norton,New York.

Wayne, S. J. (1978). The LegislativePresidency,Harper and Row, New York.

Wildavsky,A. (1966). The two presidencies.Trans-action.IV (December): 7.

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Wed, 3 Sep 2014 04:20:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Você também pode gostar

- Gibbons and Katz, Layoffs and Lemons PDFDocumento31 páginasGibbons and Katz, Layoffs and Lemons PDFVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Bot in AsiaDocumento42 páginasBot in AsiaVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Attitudes and Awareness Toward ASEANDocumento73 páginasAttitudes and Awareness Toward ASEANAinun HabibahAinda não há avaliações

- SchultzDocumento41 páginasSchultzCathy GacutanAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Financial Liberalization and Poverty PDFDocumento29 páginas2 Financial Liberalization and Poverty PDFVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Socio-Economic Development AseanDocumento13 páginasSocio-Economic Development AseanVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Yates v. United States: DecisionDocumento46 páginasYates v. United States: DecisionFindLawAinda não há avaliações

- Corporate Governance in Asian CountriesDocumento75 páginasCorporate Governance in Asian CountriesVer Madrona Jr.100% (1)

- Education SystemsDocumento87 páginasEducation SystemsVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Bruno Simma, Universality of International Law From The Perspective of A PractitionerDocumento33 páginasBruno Simma, Universality of International Law From The Perspective of A PractitionerVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Citizen Support For Trade LiberalizationDocumento24 páginasCitizen Support For Trade LiberalizationVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Boserup, Development TheoryDocumento12 páginasBoserup, Development TheoryVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Corruption in AfricaDocumento58 páginasCorruption in AfricaVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Globalization and International TradeDocumento7 páginasGlobalization and International TradejassimAinda não há avaliações

- Globalization and Within Country Income InequalityDocumento28 páginasGlobalization and Within Country Income InequalityVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Ecologism and The Politics of Sensibilities: Andrew HeywoodDocumento6 páginasEcologism and The Politics of Sensibilities: Andrew HeywoodVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- What Are Levels of Analysis and What Do They Contribute To International Relations Theory?Documento23 páginasWhat Are Levels of Analysis and What Do They Contribute To International Relations Theory?Ver Madrona Jr.100% (2)

- Hettne, Development of Development TheoryDocumento21 páginasHettne, Development of Development TheoryVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- International Labour Rights Overview February 2015Documento5 páginasInternational Labour Rights Overview February 2015Ver Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- 7 BerindanDocumento19 páginas7 BerindanVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Johnson and European Integration: A Missed Chance For Transatlantic PowerDocumento27 páginasJohnson and European Integration: A Missed Chance For Transatlantic PowerVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Preparing Europe For The Unforeseen, 1958-63Documento25 páginasPreparing Europe For The Unforeseen, 1958-63Ver Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- US CounterinsurgencyPolicy in the Philippines: A Post-PositivistAnalysisDocumento25 páginasUS CounterinsurgencyPolicy in the Philippines: A Post-PositivistAnalysisVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- The External Dimension of EU Counter - Terrorism Relations: Competences, Interests, and InstitutionsDocumento22 páginasThe External Dimension of EU Counter - Terrorism Relations: Competences, Interests, and InstitutionsVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- SCHROEDER, Strategy by StealthDocumento21 páginasSCHROEDER, Strategy by StealthVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- 7 BerindanDocumento19 páginas7 BerindanVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Theories of European IntegrationDocumento23 páginasTheories of European IntegrationVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- At The Heart of IntegrationDocumento29 páginasAt The Heart of IntegrationVer Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- BergmannNiemann Theories of European Integration Final Version 00000003Documento23 páginasBergmannNiemann Theories of European Integration Final Version 00000003Ver Madrona Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Mintwise Regular Commemorative Coins of Republic IndiaDocumento3 páginasMintwise Regular Commemorative Coins of Republic Indiashridhar_9788Ainda não há avaliações

- Halalan 2019 DAVAO CITY Election ResultsDocumento1 páginaHalalan 2019 DAVAO CITY Election ResultsJumillah Roisin Kalimpo DilangalenAinda não há avaliações

- Lec9 Lahore Resolution 1940Documento13 páginasLec9 Lahore Resolution 1940Muhammad Adil HussainAinda não há avaliações

- Antique - MunDocumento41 páginasAntique - MunireneAinda não há avaliações

- Aoife Moore The Long GameDocumento336 páginasAoife Moore The Long GameEamonAinda não há avaliações

- Atong Paglaum Vs ComelecDocumento2 páginasAtong Paglaum Vs ComelecJen AniscoAinda não há avaliações

- Form 7A I Phase Final (English) - Compressed PDFDocumento264 páginasForm 7A I Phase Final (English) - Compressed PDFDisability Rights AllianceAinda não há avaliações

- BSC3R 2019Documento12 páginasBSC3R 2019Ajay ThakurAinda não há avaliações

- Mexican Geography HighlightsDocumento36 páginasMexican Geography HighlightsMaestro LazaroAinda não há avaliações

- Cambodia National Rescue Party DissolvedDocumento11 páginasCambodia National Rescue Party DissolvedEvelyn TocgongnaAinda não há avaliações

- KRUPSKAYA, N. (Livro, Inglês, 1933) Reminiscences of Lenin PDFDocumento292 páginasKRUPSKAYA, N. (Livro, Inglês, 1933) Reminiscences of Lenin PDFAll KAinda não há avaliações

- James Paris Election Leaflet - April 17th 2012Documento2 páginasJames Paris Election Leaflet - April 17th 2012Greg FosterAinda não há avaliações

- (Manuel - Caballero) Latin America and The Com Intern, 1919-1943Documento223 páginas(Manuel - Caballero) Latin America and The Com Intern, 1919-1943Enrique Olaf Cordova Garza100% (1)

- Tory Councillor DossierDocumento48 páginasTory Councillor DossierMatesJacob100% (2)

- List of Candidates in Jefferson CountyDocumento10 páginasList of Candidates in Jefferson CountyNewzjunkyAinda não há avaliações

- Abdul Samad Khan AchakzaiDocumento1 páginaAbdul Samad Khan AchakzaiWaQar KhAn Mehsud100% (1)

- Virthli 6 2 24Documento2 páginasVirthli 6 2 24rafitaliaruatsangaAinda não há avaliações

- Elamkulam Manakkal Sankaran NamboodiripadDocumento2 páginasElamkulam Manakkal Sankaran NamboodiripadsarayooAinda não há avaliações

- POLITICS: KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTSDocumento3 páginasPOLITICS: KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTSElena Gonzalez MarquezAinda não há avaliações