Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Important Quotations Explained

Enviado por

Mirela GrosuDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Important Quotations Explained

Enviado por

Mirela GrosuDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Important Quotations Explained

1.

Amor matris: subjective and objective genitive.

This quotation, part of Stephens inner monologue, appears in Episode

Two. Amor matris translates to mother love, a concept that Stephen ponders

while giving extra help to his student Sargent. Sargent reminds Stephen of

himself at the same ageStephen was similarly dirty and disheveled, a child

only a mother could love. Stephen thinks of mother love frequently in Ulysses

he contrasts the concrete, bodily reality of a mothers love to the disconnected,

tension-ridden relation between a father and a child. In Episode Nine, Stephen

calls amor matris the only true thing in life, and skeptically identifies paternity as

a legal fiction. The phrase subjective and objective genitive refers to the

confusion about the translation of amor matrisit can be either a childs love for

a mother or a mothers love for a child. This touches on Stephens difficulties in

deciding whether to be an active or a passive being. In Episode Nine, he frames

the choice this way: Act. Be acted on. In the quotation from Episode Two

above, we see Stephen trying to understand the ethics and power relations

involved in his teacher-stu-dent relationship with Sargent in terms of the

compassion entailed by mother love.

2.

History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.

This quotation appears in Episode Two, during Stephens conversation with Mr.

Deasy. With Sargent and his class earlier in Episode Two, Stephen was the

reluctant teacher, and now Deasy attempts to position him as the pupil. But

Stephen blithely maneuvers out of this role by way of a few cryptic statements,

such as the one above. Here, Stephens version of history as a nightmare is an

explicit challenge to Deasys conception of history as moving toward one goal

(the manifestation of God), and an implicit challenge to Hainess version of

history in Episode One as something impersonal and cut off from the present (It

seems history is to blame). Stephens conception of history has several

meanings. Stephen sees history, and Irish history in particular, as filled with

violenceDeasys and Hainess conceptions of history enable this violence by

excluding certain people from history in Deasys case (those who do not believe

in a Christian God) and by absolving those who perpetrate violence from any

blame in Hainess case. Stephens comment also refers to his conception of the

tensions between art and historyStephen sees history as an impossible chaos

and art as a way of representing that chaos in an ordered fashion. Finally,

Stephens statement is also an extremely personal onehis own history is

something he is trying to overcome. At the opening of Ulysses, Stephen is feeling

particularly hopeless about the possibility of rising above the circumstances of his

upbringing.

3.

What is it? says John Wyse. A nation? says Bloom. A nation is the same people living in the

same place. By God, then, says Ned, laughing, if thats so Im a nation for Im living in the same

place for the past five years.

This dialogue occurs in Episode Twelve, during the confrontation scene at

Barney Kiernans pub. Led by the citizen, the men at Barney Kiernans explicitly

identify Bloom as an outsider, his Jewish-Hungarian roots being incompatible

with their essentialist conception of Irishness as a racial and Catholic category.

Here, Blooms conception of a nation may seem excessively loose (especially

when he backs up several lines later to qualify, Or in different places), but

Blooms position on nationality as a self-selected category is part of the triumph

of Blooms compassionate humanism over the violent essentialism of the citizen

and others. Ned Lamberts sarcastic response to Bloom here is an example of

another way in which Bloom is repeatedly marked as an outsiderthe Dublin

men with whom Bloom associates are skilled in using mockery and sarcasm to

establish authority over others, while Bloom does not use humor in this way.

4.

. . . each contemplating the other in both mirrors of the reciprocal flesh of theirhisnothis fellowfaces.

This quotation occurs in Episode Seventeenit is a narrative description of

Stephen and Blooms wordless interaction in Blooms garden just before Stephen

leaves. Their meeting is in no sense ideala father-son connection is not

explicitly made, and Stephen declines to stay the night and probably will not see

Bloom again. Yet the narrative of Episode Seventeen manages to convey their

union as symbolically meaningful, by tapping various themes. This sentence

manages to include an optimistic set of thematic connotations: the recognition

theme from (disguised) Odysseus and Telemachuss meeting in The Odyssey;

and an idea of the father-son relationship involving versions of the same bodily

self (flesh). The reciprocal aspect of their meeting implies that Stephen has

managed to find a medium in the troublesome dynamic of activity-passivity. The

theirhisnothis narrative play also manages to suggest that the meeting is an

ideal balance between a coming-together and a realistic recognition of

otherness.

5.

. . . and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around

him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was

going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

Mollys final words seem to refer immediately to her memory of accepting

Blooms proposition of marriage during their day spent on Howth. However, the

ambiguity of the many masculine pronouns in Mollys monologue also exists here

in the same paragraph, she remembers a similar outdoor scene of love with Lt.

Mulvey, and the ambiguity of this seeming affirmation of the Blooms marriage is

typical of Joyces endings. However, the looseness of Mollys language in these

final lines also enacts a combination of the immediate realistic level of the text

with the idealistic, symbolic levelMollys Yes here is an unqualified affirmative

of natural life and of physical and emotional love.

Você também pode gostar

- Borderline Narcissistic and Schizoid Adaptations (Greenberg, 2016)Documento382 páginasBorderline Narcissistic and Schizoid Adaptations (Greenberg, 2016)George Schmidt87% (15)

- Translations (Brian Friel) Essay A Level EnglishDocumento3 páginasTranslations (Brian Friel) Essay A Level EnglishFrozentapeAinda não há avaliações

- Gender Identity in Rape of The Lock and Paradise LostDocumento8 páginasGender Identity in Rape of The Lock and Paradise LostOmabuwa100% (1)

- Timo Pfaff On Sarah Kane's CleansedDocumento15 páginasTimo Pfaff On Sarah Kane's CleansedAndi TothAinda não há avaliações

- Beloved - Tony MorrisonDocumento4 páginasBeloved - Tony Morrisonasánchez_vásquez100% (1)

- Stream of Consciousness in A Portrait of The Artist As A Young MNDocumento5 páginasStream of Consciousness in A Portrait of The Artist As A Young MNRaheel FarooqiAinda não há avaliações

- Essay On Look Back in AngerDocumento2 páginasEssay On Look Back in AngerVidal Gonzalez PereiraAinda não há avaliações

- Waste Land As Social DocumentDocumento41 páginasWaste Land As Social DocumentSabah Mubarak100% (1)

- Death of A NaturalistDocumento4 páginasDeath of A Naturaliststefania golaiasAinda não há avaliações

- Epiphany in James JoyceDocumento4 páginasEpiphany in James JoyceATIQ UR REHMANAinda não há avaliações

- YLE Placement TestDocumento4 páginasYLE Placement TestMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- 1st and 2nd UNIT TEST in PERSONAL DEVELOPMENTDocumento2 páginas1st and 2nd UNIT TEST in PERSONAL DEVELOPMENTEam Osar100% (1)

- Grammar AliveDocumento141 páginasGrammar AliveGiang Nguyet Minh100% (3)

- George HerbertDocumento12 páginasGeorge HerbertkishobranAinda não há avaliações

- Themes James Joyce UlyssesDocumento4 páginasThemes James Joyce UlyssesMemovici IoanaAinda não há avaliações

- Dramatic Conflict in A Streetcar Named DesireDocumento4 páginasDramatic Conflict in A Streetcar Named Desirelarisabebek100% (1)

- First 90 Days Worksheet-LeaderDocumento2 páginasFirst 90 Days Worksheet-LeaderPavan Vasudevan33% (6)

- Sinapsis Clasa 1Documento41 páginasSinapsis Clasa 1ank832 monica100% (1)

- Play English Sinapsis 4Documento41 páginasPlay English Sinapsis 4Irina BorzaAinda não há avaliações

- The Importance of Stream of Consciousness in James JoyceDocumento16 páginasThe Importance of Stream of Consciousness in James JoyceIggy Cossman100% (1)

- Ulyssess by James Joyce: Themes, Characters, Symbols, StyleDocumento21 páginasUlyssess by James Joyce: Themes, Characters, Symbols, StyleDaniela Matei ŞoraAinda não há avaliações

- Ulysses Themes, Motifs, SymbolsDocumento4 páginasUlysses Themes, Motifs, SymbolsLuz VazquezAinda não há avaliações

- Song of Solomon Essay ThesisDocumento8 páginasSong of Solomon Essay Thesisanashahwashington100% (2)

- Making History by Brian Friel: A Pivotal MomentDocumento5 páginasMaking History by Brian Friel: A Pivotal MomentSophie HartfieldAinda não há avaliações

- The Use of Stream-Of-Consciousness Technique in Joyce's NovelDocumento4 páginasThe Use of Stream-Of-Consciousness Technique in Joyce's NovelNa NanAinda não há avaliações

- James JoyceDocumento30 páginasJames JoyceRichard SouthardAinda não há avaliações

- Conjugal Love Conjugal Love Refers To Love in A Conjugal Relationship, That Is, in A Marriage, Since The WordDocumento4 páginasConjugal Love Conjugal Love Refers To Love in A Conjugal Relationship, That Is, in A Marriage, Since The WordAAQIBAinda não há avaliações

- Poetry Questions SyllabusDocumento31 páginasPoetry Questions Syllabusayaelfarisi08Ainda não há avaliações

- Songs of Innocence - NotesDocumento2 páginasSongs of Innocence - NotesMonir AmineAinda não há avaliações

- Shakespeare Revised Research EssayDocumento8 páginasShakespeare Revised Research Essayapi-640451375Ainda não há avaliações

- "The Dead" ("Dubliners") : James JoyceDocumento3 páginas"The Dead" ("Dubliners") : James JoyceannaAinda não há avaliações

- Eng 11-Wfq Leonardo (Literary Analyis)Documento7 páginasEng 11-Wfq Leonardo (Literary Analyis)Dayanne LeonardoAinda não há avaliações

- PunishmentDocumento5 páginasPunishmenttanu kapoorAinda não há avaliações

- Metaphor StanfordDocumento52 páginasMetaphor StanfordMikel Angeru Luque GodoyAinda não há avaliações

- The Open Boat EssayDocumento5 páginasThe Open Boat Essayafabggede100% (2)

- Poetry Analysis - 'Punishment' - by Seamus HeaneyDocumento2 páginasPoetry Analysis - 'Punishment' - by Seamus HeaneyDilek Mustafa100% (1)

- On Trying To Talk With A ManDocumento4 páginasOn Trying To Talk With A Manthodorosmoraitis100% (1)

- Matric Poetry Pack BinderDocumento18 páginasMatric Poetry Pack BinderBuhle JoyAinda não há avaliações

- Common Man Essay, He Argues: "I Believe That The Common Man Is As Apt A Subject ForDocumento1 páginaCommon Man Essay, He Argues: "I Believe That The Common Man Is As Apt A Subject ForSarah Elizabeth LomaxAinda não há avaliações

- Pec1 Víctor Monge CuarteroDocumento3 páginasPec1 Víctor Monge CuarteroVíctor María Monge CuarteroAinda não há avaliações

- Studying English Literature: The Role of Chorus in Samson AgonistesDocumento3 páginasStudying English Literature: The Role of Chorus in Samson AgonistesShreyashree PradhanAinda não há avaliações

- Glossery of Terms Related To NarrativeDocumento5 páginasGlossery of Terms Related To NarrativeTaibur RahamanAinda não há avaliações

- Descovering Themes and Motifs in James Joyce's "The Dead" and "Ulysses"Documento5 páginasDescovering Themes and Motifs in James Joyce's "The Dead" and "Ulysses"Aura LalaAinda não há avaliações

- "Towards A Conceptual Lyric" by Marjorie PerloffDocumento9 páginas"Towards A Conceptual Lyric" by Marjorie PerloffbeginningtheAinda não há avaliações

- First Death in Nova Scotia - PresentationDocumento3 páginasFirst Death in Nova Scotia - PresentationthomwacheAinda não há avaliações

- Translating The Body: Towards An Erotics of Translation: Kevin WestDocumento25 páginasTranslating The Body: Towards An Erotics of Translation: Kevin WestHristo BoevAinda não há avaliações

- HeaneyDocumento5 páginasHeaneyekc113Ainda não há avaliações

- When I Was One and TwentyDocumento3 páginasWhen I Was One and TwentyGalrich Cid CondesaAinda não há avaliações

- 202 2013 1 BDocumento9 páginas202 2013 1 B53078691Ainda não há avaliações

- Existence, Contingency and Mourning in Cavell's HamletDocumento14 páginasExistence, Contingency and Mourning in Cavell's HamletcarouselAinda não há avaliações

- Blackberry Picking Poem Thesis StatementDocumento6 páginasBlackberry Picking Poem Thesis StatementHelpWithWritingAPaperUK100% (2)

- Malcolm X PlaylistDocumento7 páginasMalcolm X PlaylistLiv DussereAinda não há avaliações

- Literary Devices (PAIR)Documento6 páginasLiterary Devices (PAIR)David GamboaAinda não há avaliações

- Symbolism in Hills Like White ElephantsDocumento3 páginasSymbolism in Hills Like White ElephantsDamian Alejandro SalinasAinda não há avaliações

- Term PaperDocumento10 páginasTerm PaperSamik DasguptaAinda não há avaliações

- Gene M. Moore, "The World of Words in Joyce's - Portrait - and Musil's - Turless - "Documento3 páginasGene M. Moore, "The World of Words in Joyce's - Portrait - and Musil's - Turless - "PACAinda não há avaliações

- English LiteratureDocumento9 páginasEnglish Literatureandraduk19Ainda não há avaliações

- A Question of PowerDocumento22 páginasA Question of PowerLaarnie Domanais AsogueAinda não há avaliações

- A Critical Guide To TCITDocumento6 páginasA Critical Guide To TCITKimberley WyattAinda não há avaliações

- Educational Experience EssaysDocumento7 páginasEducational Experience Essaysafhbebhff100% (2)

- Annotated Glossary FinalDocumento21 páginasAnnotated Glossary Finalapi-36964010% (1)

- Adapted From Critical Theory Today: A User-Friendly Guide by Lois Tyson andDocumento5 páginasAdapted From Critical Theory Today: A User-Friendly Guide by Lois Tyson andwinchel sevillaAinda não há avaliações

- Academic Writing HandoutDocumento6 páginasAcademic Writing HandoutSachini SeneviratneAinda não há avaliações

- 20th Century British Reading JournalDocumento27 páginas20th Century British Reading JournalAndie FoleyAinda não há avaliações

- The Good MorrowDocumento3 páginasThe Good Morrowankita420Ainda não há avaliações

- JDG BüchnerDocumento25 páginasJDG Büchnerdana AAinda não há avaliações

- File 1597234654 PDFDocumento41 páginasFile 1597234654 PDFCuibuș Mihaela LauraAinda não há avaliações

- T TP 1662558213 Find The Adjectives Activity Ver 1Documento2 páginasT TP 1662558213 Find The Adjectives Activity Ver 1Mirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- File 1597234815 PDFDocumento41 páginasFile 1597234815 PDFFlorentina BugaAinda não há avaliações

- 26xanimal BraveryDocumento1 página26xanimal BraveryMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Find Classroom WordsDocumento1 páginaFind Classroom WordsMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- 16mar ReadingDocumento2 páginas16mar ReadingMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Clauses of ResultfDocumento1 páginaClauses of ResultfMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Job RequirementsDocumento1 páginaJob RequirementscdjrhsAinda não há avaliações

- Slackx2 PDFDocumento2 páginasSlackx2 PDFMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Some or AnyDocumento1 páginaSome or AnyMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Shops and ShoppingDocumento2 páginasShops and ShoppingMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- YLE Placement Test PDFDocumento4 páginasYLE Placement Test PDFMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Coincidence X 2Documento3 páginasCoincidence X 2Mirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Princess Paper DollsDocumento1 páginaPrincess Paper DollsRaluca RalucaAinda não há avaliações

- Classroom 1Documento1 páginaClassroom 1Mirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Restaurant PDFDocumento2 páginasRestaurant PDFMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Coincidence X 2Documento7 páginasCoincidence X 2Mirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Job RequirementsDocumento1 páginaJob RequirementscdjrhsAinda não há avaliações

- Plasticx 2Documento1 páginaPlasticx 2Mirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Change The Verb Into The Past Simple, Find Them in The Word Search and Then Translate The Sentences Into RomanianDocumento2 páginasChange The Verb Into The Past Simple, Find Them in The Word Search and Then Translate The Sentences Into RomanianMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Riverx2 PDFDocumento1 páginaRiverx2 PDFMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Scribd 1Documento7 páginasScribd 1Mirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Leda and The SwanDocumento1 páginaLeda and The SwanMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Scribd 1Documento7 páginasScribd 1Mirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- Body PartsDocumento1 páginaBody PartsMirela GrosuAinda não há avaliações

- The Learning Zone ModelDocumento6 páginasThe Learning Zone ModelShosho NasraweAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing Creative Media's Social ImpactDocumento23 páginasAssessing Creative Media's Social ImpactPraise NkalaAinda não há avaliações

- Advanced Business Research Methods by Solomon Molla (PHD)Documento17 páginasAdvanced Business Research Methods by Solomon Molla (PHD)Aklilu TadesseAinda não há avaliações

- Dicourse Analysis and Politeness TheoryDocumento13 páginasDicourse Analysis and Politeness TheoryNoviaAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnostics Crim Dec2022Documento3 páginasDiagnostics Crim Dec2022RODOLFO JR. CASTILLOAinda não há avaliações

- DLL - Mathematics 5 - Q4 - W2Documento9 páginasDLL - Mathematics 5 - Q4 - W2JOAN MANALOAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study No. 1 (L8)Documento3 páginasCase Study No. 1 (L8)KRIZEL JANE ENRIQUEZAinda não há avaliações

- Developmental and Social Factors and Individual DifferencesDocumento15 páginasDevelopmental and Social Factors and Individual DifferencesCherry Blossom LeciasAinda não há avaliações

- Decimals LessonDocumento3 páginasDecimals Lessonapi-697312628Ainda não há avaliações

- Conditions For Effective Market SegmentationDocumento2 páginasConditions For Effective Market SegmentationBen MathewsAinda não há avaliações

- Background of The Study: Factors Affecting The Number of Dropout Rate of Narra National High School SY 2015-2016Documento10 páginasBackground of The Study: Factors Affecting The Number of Dropout Rate of Narra National High School SY 2015-2016Shiela Mae RegualosAinda não há avaliações

- M C M Pramoedya Ananta Toer: y Ell AteDocumento8 páginasM C M Pramoedya Ananta Toer: y Ell AteSocǩǐ ǏrlandezAinda não há avaliações

- Learning-Theories Link123Documento41 páginasLearning-Theories Link123Ann AguantaAinda não há avaliações

- AQA Psychology Issues and Debates Knowledge Book Suggested AnswersDocumento28 páginasAQA Psychology Issues and Debates Knowledge Book Suggested Answersyasirshahbaz25Ainda não há avaliações

- Dissertation Help ForumsDocumento6 páginasDissertation Help ForumsBestCustomPapersUK100% (1)

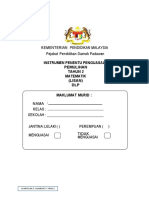

- Instrumen Penentu Penguasaan Numerasi Tahun 2 DLP LisanDocumento19 páginasInstrumen Penentu Penguasaan Numerasi Tahun 2 DLP LisancollinAinda não há avaliações

- Sherlock HolmesDocumento8 páginasSherlock HolmesSwaroop SrinivasanAinda não há avaliações

- (Template) Unit 1, Test 1 - Grupa ADocumento2 páginas(Template) Unit 1, Test 1 - Grupa ApatixAinda não há avaliações

- Silvera Martinussenog Dahl 2001Documento8 páginasSilvera Martinussenog Dahl 2001Vandana VashishtAinda não há avaliações

- The Invisible Wallflower Marries An Upstart Aristocrat After Getting Dumped For Her Sister! Vol 1Documento222 páginasThe Invisible Wallflower Marries An Upstart Aristocrat After Getting Dumped For Her Sister! Vol 1thayenebrandaonutriAinda não há avaliações

- Statistical StudiesDocumento25 páginasStatistical StudiesMathew RickyAinda não há avaliações

- MODALITIESDocumento6 páginasMODALITIESCYRELLE ANNE MALLARIAinda não há avaliações

- As8 PR1Q3 G11 CasipitDocumento7 páginasAs8 PR1Q3 G11 CasipitGladice FuertesAinda não há avaliações

- Cel2106 SCL Worksheet 13 (Mohd Syafiq - 196449)Documento3 páginasCel2106 SCL Worksheet 13 (Mohd Syafiq - 196449)afiyqAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 5Documento7 páginasChapter 5Luelle PacquingAinda não há avaliações

- RPIC - FO - 0023 - Ethics Application Procedure-4Documento7 páginasRPIC - FO - 0023 - Ethics Application Procedure-4JHON LLOYD LALUCESAinda não há avaliações

- Math Club 3Documento3 páginasMath Club 3etheyl fangonAinda não há avaliações