Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

With Fortunes To Be Made or Lost - Will Natural Gas Find Its Footing

Enviado por

diponogoroTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

With Fortunes To Be Made or Lost - Will Natural Gas Find Its Footing

Enviado por

diponogoroDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Executive Agenda

With Fortunes to Be Made

or Lost, Will Natural Gas

Find Its Footing?

The U.S. shale gas market is out of balance with

production outstripping demand. But when the glut

ends, how will the market shake out? All signs point

to a rebalance by 2020, when the free market kicks in.

With Fortunes to Be Made or Lost, Will Natural Gas Find Its Footing?

Executive Agenda

Despite all the talk about shale gas developmentthe potential environmental consequences of

hydraulic fracturing, the potential to replace coal with gas for generating electricity, the potential

for the United States to export liquefied natural gas (LNG)none of it addresses the bigger

picture: The market is structurally out of balance, and it cant stay this way. The technological

triumph of shale gas has led to production that far outstrips demand, and if this were a normal

market, price and demand shifts would have already delivered a quick rebalancing.

But shale gas is not a normal market and a rebalancing is not likely in this complex ecosystem

where a wide array of players have diverging incentives and investment horizons. Over the past 20

years, gas prices have fluctuated between $2 and $15 per million BTU. At the low end, the producers are not viable, and at the high end, potential users of gas cannot afford to use it. Will we face

more years of such fluctuations before achieving balance, especially since numerous decisions

affecting that balance are still up in the air? And yet, bets must be placed now. Infrastructure must

be built. With fortunes to be made or lost, these decisions must be as informed as possible.

A Quest for Balance

The hydrocarbon business is all about balance. Balance among production, refining and

converting, and marketing has been a vaunted but elusive goal for more than a century, as

Daniel Yergin chronicles in The Prize, a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the global oil industry.

An investment in one industry sector (for example, upstream exploration and production) may

be useless unless paired with appropriate investments in other sectors (such as downstream

selling and marketing). In the oil industry, factors encouraging balance include vertical

integrationglobal companies that control everything from exploration to deliveryand

regulation of production, either overtly through organizations such as OPEC or more naturally

through high barriers to entry. In the gas industry, those factors are lacking.

So the relevant questions are not so much Is the shale gas boom real? Or Is it here to stay?

(The short answer is yes.) The question companies should be asking is How will the natural

gas glut rebalance in the long term? As an analogy, consider the U.S. deregulation of natural

gas wellhead prices in 1989. Was it real? Was it here to stay? Yes, but after a brief period of

sustained low prices in the 1990s, the industry has been plagued with volatility. Prices have

bounced up and down, sometimes benefitting producers, sometimes end users. The problem

has been balance. When prices were low, up went the infrastructure of gas-fired power plants

and pipelines. After the investments were locked in, all that demand sent gas prices so high

that much of it could not be used.

Will the same thing happen again? We cant say for sure because the factors are different and

some of them are yet to be determined. But we can say this: The industry is still not structured to

achieve win-win scenarios. It is not integrated, which means that big trends in one area can go

almost unnoticed in another. Understanding whats going to happen requires first understanding

who all the players are.

An Uncoordinated Set of Actors

The U.S. shale gas ecosystem comprises a set of players with different incentives and investment

horizons that have grown up mostly independent of each other and are generally not inclined to

understand the motivations of the other players. The shale gas family includes a variety of actors:

With Fortunes to Be Made or Lost, Will Natural Gas Find Its Footing?

Executive Agenda

Independent producers focus on short-term plays and have an investment time horizon

of just a few years. They are not afraid to take risks, have few barriers to entry, and can bring

on capacity quickly and inexpensively. But if gas prices stay below $4 per million BTU, many

players with predominantly dry gas portfolios will continue to struggle and possibly go out

of business.

Super majors and global producers take a longer view on their investments and can afford to

delay investment in certain parts of the world if local conditions are not favorable.

Midstream players have a longer view on investments, but they take advantage of geographic

and capacity-based market differentials to invest in pipelines, gas processing, and fractionation.

Gas exporters are eyeing liquefaction facilities on the coasts that could competitively export

LNG and take advantage of high prices abroad if the price spread between the United States

and overseas markets stays above $5. Although 4.5 trillion cubic feet of capacity has been

proposed, these facilities could cost up to $10 billion per trillion cubic foot and take a minimum

of five years to permit and build.

Chemical companies are looking at natural gas liquids (NGL) as feedstock. Low-cost ethane

(as a substitute for byproducts of crude oil refining), for example, makes polyethylene cheaper

to produce in the United States than anywhere in the world except the Middle East. So the

industry could build eight to 10 (or more) new gas crackers at approximately $2 billion apiece,

including some downstream investments, but it would need confidence in ethane prices

being competitive for 10 or more years.

Instead of asking Is the shale gas boom

here to stay?, we should be asking How

will the natural gas glut rebalance in

the long term?

Power generators want low-cost gas to generate electricity. Before the shale boom, existing

gas plants were operating at less than 50 percent of capacity. However, they can ramp up

quickly and squeeze out other forms of power generation, primarily coal. If power generators

knew gas prices would stay below $6, they could begin replacing existing coal plants with gas

plants that take just two to three years to build.

The advocates of new usessuch as T. Boone Pickens, Chesapeake, and GEwill look at

compressed natural gas (CNG) to fuel cars and trucks if gas prices are low compared to oil.

Such plans will require huge investments over long timeframes to build CNG infrastructure,

fueling stations, and vehicle fleets.

Some of these players are already pairing up. Chemical companies are signing long-term ethane

supply agreements with shale NGL producers and midstream companies. LNG companies are

doing the same with their suppliers and their customers. Others are staying single for now, at

least until there is more (or a narrower range) price certainty and fewer wildcards.

With Fortunes to Be Made or Lost, Will Natural Gas Find Its Footing?

Executive Agenda

Five Possible Futures, One Likely Scenario

If supply and demand were stable and investment cycles were shorter, it would be easy for

market forces to align them. But the U.S. market for natural gas and NGLs is driven by several

diverse and unpredictable variables: the global economy, oil prices, energy and environmental

policies, a rise in the global gas supply, or technological advances that are still unknown (see

sidebar: Predicting the Unpredictable). Although these variables could interact in any number of

permutations, our analysis finds five scenarios that could capture a range of potential outcomes.

The most likely scenario, which we call free markets, involves the least dramatic changes from

current conditions. In this scenario, GDP growth is modest, oil prices remain within current

trading ranges, LNG export becomes a reality, and no major global natural gas production or

technological advance affects the balance of forces seen today.

We believe the price of natural gas in the free-markets scenario will find equilibrium by 2020 in

the $6 to $7 range. Any lower than that and production from dry-gas wells would not be

profitable and would not increase sufficiently to meet demand; any higher and demand from

power plants will wane. But in this range, demand is high in all major sectors, leading to high

margins for producers and strong capital investments.

Predicting the Unpredictable

If supply and demand were stable

and investment cycles were

shorter, it would be easy for market

forces to align them. But the U.S.

market for natural gas and NGL

is unpredictable, with several

diverse and volatile factors.

Theres the global economy.

Global growth will drive demand

for energy and materials. If the

recovery gains momentum and

global gross domestic product

(GDP) rises by 3 to 5 percent

annually, demand will be high. But

if global GDP stagnates and global

trade drops, lower demand for

electricity, chemicals, and natural

gas in other markets could drop

prices across the board. Oil prices

are also unpredictable. At the

current price spread between oil

and natural gas, chemical

production from NGLs is

attractive. But if oil prices drop to

$60 per barrel and are forecasted

to remain there, gas production

falls and chemical companies

delay investments in gas crackers.

Energy and environmental

policies could upset industry

dynamics. Environmental policy

on hydraulic fracturing will

drive the cost of drilling and

completion of wells and could

stop it altogether if there are

major incidents. Or the United

States could restrict LNG exports

to foster energy independence

or to support jobs and economic

growth through a cost-competitive energy advantage, or it

could allow LNG exports in

a more free-markets policy.

Also, environmental regulators

concerned about greenhouse

gas emissions might impose

carbon taxes, air quality

restrictions, and carbon dioxide

emission regulations that make

coal-fired options more

expensive, pushing power

generators to substitute coal

with natural gas.

shale gas advantage, making

LNG exports less attractive.

And if the new shale plays are

rich in NGLs, U.S. chemical

company exports will suffer.

Finally, we dont know where the

next technological advance will

come from. Will it be in exploration

technologies to unlock stranded

resources such as gas hydrates or

to further lower production costs

of existing plays? Will it be in

breakthrough innovation that will

alter the economics of processes

such as gas-to-liquid conversion?

It is hard to predict, but if the next

advance is in solar, wind, oil, or

coal carbon capture and storage,

one of those competing energy

sources might leapfrog gas and

gain advantage.

Increased gas supply, with rapid

development of gas in other

countries could halt the U.S.

With Fortunes to Be Made or Lost, Will Natural Gas Find Its Footing?

Executive Agenda

Although the free-markets scenario is the most likely in our analysis, the outcome of global

events and governmental actions could lead us down other paths. There are four other

possible scenarios:

Troubled times. A geopolitical event triggers a disruption in oil supply, sending oil prices up

and the global economy into a double-dip recession. Natural gas demand collapses to 20

percent below the free-market scenario level.

Limited export. The U.S. government decides to limit natural gas exports and provides support

for other fuels in an effort to achieve energy independence, thus depressing natural gas demand.

Global gas competition. Other major economies are successful in developing wet shale plays.

As a result, demand falls for both LNG exports and ethane-based chemicals from the United

States, challenging the overall economics of shale gas plays in North America.

High output. Robust global GDP growth and lack of global shale developments lead to the

highest level of U.S. natural gas demand.

These scenarios represent a combination of various, and sometimes drastic, supply and

demand discontinuities. Nevertheless, the resulting gas prices are spread across a surprisingly

narrow range of $5 to $8 per thousand cubic feet (mcf) (see figure). We believe market trends

point to a strong future for natural gas and its ability to pull prices up structurally, with upstream

production economics determining the floor price and competition between coal and gas

defining the ceiling price.

Figure

Natural gas 2020 price scenarios

Natural gas price ($/MMBtu)

$12

$11

$10

Global economies

collapsing

Demand for natural

gas slowing

Natural gas

restrictions increasing to stimulate

domestic economy

Global gas development putting pricing

pressure on NGLs and

U.S.-based chemicals

Competition from

coal-fired power

generation

Domestic demand

moderating at high

NG prices

$9

$8

$7

$6

$5

$4

$3

$2

$1

$0

Gas more attractive

than coal

Supply being

rationalized to

eliminate wasteful

production

Gas more attractive

than coal

Modest global GDP

sustaining NGL

prices

Supply being

rationalized

Troubled times

Limited export

Demand for NGL

falling, forcing more

supply rationalization

GDP sustaining

domestic demand

Gas equaling coal

Global gas

competition

Demand for natural

gas rising as LNG

is exported and

global shale

development falls

GDP rising

Supply being

rationalized

Free markets

CO2 regulations

favoring gas

No major global

shale developments

GDP growing

New demand

channels emerging

for GTL and CNG

High output

Notes: MMBtu is one million British thermal units, GDP is gross domestic product, NGL is natural gas liquids, LNG is liquefied natural gas,

GTL is gas to liquids, and CNG is compressed natural gas.

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis

With Fortunes to Be Made or Lost, Will Natural Gas Find Its Footing?

Executive Agenda

Finding Balance

One of the biggest difficulties in looking forward is knowing when a current trend represents

lasting change and when it is merely a bump in the road. Shale gas represents lasting change,

but every change has many paths to balance. And on the road from here to long-term balance,

there will undoubtedly be many short-term irritationsa mild winter, a Middle East crisisthat

will send some analysts to wrong conclusions.

In our free-market scenario, the price of

natural gas finds equilibrium by 2020 in

the $6 to $7 range.

The regulatory certainty and more balanced pricing reflected in the free-market scenario could

provide a foundation of stabilized demand on which to build investments. Thats a likely path to

long-term balance, but even it would be filled with both short-term bumps and more serious

detours caused by players with different incentives.

Because of those bumps, prices during the transition will be volatile. When they are low, some

producers may be forced out of the market. When they are high, capacity investments may be

delayed. Disruptive events such as an oil-price collapse or a safety or environmental incident

may dramatically reduce supply. Any one of these detours could be devastating to an individual

player. If bigger than expected, one or more could transform the industry in unexpected ways,

leading to a different path and a different result.

But the same could be said about any unexpected event. More fundamentally, we can say that in

the long run, despite temporary blips, the natural gas industry will find balance. The path to get

there will take advantage of the reduced costs and expanded supplies resulting from shale gas.

It will also take advantage of the smart investments of well-informed players throughout the

complex industry ecosystem.

Authors

Patrick Haischer, partner, New York

patrick.haischer@atkearney.com

Andrew Walberer, partner, Chicago

andrew.walberer@atkearney.com

Herve Wilczynski, partner, Houston

herve.wilczynski@atkearney.com

With Fortunes to Be Made or Lost, Will Natural Gas Find Its Footing?

Executive Agenda

A.T. Kearney is a global team of forward-thinking, collaborative partners that delivers

immediate, meaningful results and long-term transformative advantage to clients.

Since 1926, we have been trusted advisors on CEO-agenda issues to the worlds

leading organizations across all major industries and sectors. A.T. Kearneys ofces

are located in major business centers in 39 countries.

Americas

Atlanta

Calgary

Chicago

Dallas

Detroit

Houston

Mexico City

New York

San Francisco

So Paulo

Toronto

Washington, D.C.

Europe

Amsterdam

Berlin

Brussels

Bucharest

Budapest

Copenhagen

Dsseldorf

Frankfurt

Helsinki

Istanbul

Kiev

Lisbon

Ljubljana

London

Madrid

Milan

Moscow

Munich

Oslo

Paris

Prague

Rome

Stockholm

Stuttgart

Vienna

Warsaw

Zurich

Asia Pacific

Bangkok

Beijing

Hong Kong

Jakarta

Kuala Lumpur

Melbourne

Mumbai

New Delhi

Seoul

Shanghai

Singapore

Sydney

Tokyo

Middle East

and Africa

Abu Dhabi

Dubai

Johannesburg

Manama

Riyadh

For more information, permission to reprint or translate this work, and all other correspondence,

please email: insight@atkearney.com.

A.T. Kearney Korea LLC is a separate and

independent legal entity operating under

the A.T. Kearney name in Korea.

2012, A.T. Kearney, Inc. All rights reserved.

The signature of our namesake and founder, Andrew Thomas Kearney, on the cover of this

document represents our pledge to live the values he instilled in our firm and uphold his

commitment to ensuring essential rightness in all that we do.

Você também pode gostar

- Where Do Great Strategies Come FromDocumento10 páginasWhere Do Great Strategies Come Fromdiponogoro100% (1)

- Royal Dutch Shell BG Group case study analyzes $70bn acquisitionDocumento7 páginasRoyal Dutch Shell BG Group case study analyzes $70bn acquisitionFattyschippy1Ainda não há avaliações

- Citadel Conversation Explores Energy Independence and Shale Gas BoomDocumento4 páginasCitadel Conversation Explores Energy Independence and Shale Gas BoomGary CaoAinda não há avaliações

- Green Investing: A Guide to Making Money through Environment Friendly StocksNo EverandGreen Investing: A Guide to Making Money through Environment Friendly StocksNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (2)

- Index File FYI: Download The Original AttachmentDocumento57 páginasIndex File FYI: Download The Original AttachmentAffNeg.Com100% (1)

- 02pa MK 3 5 PDFDocumento11 páginas02pa MK 3 5 PDFMarcelo Varejão CasarinAinda não há avaliações

- Oef 62Documento20 páginasOef 62jonnathannAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper Gas PricesDocumento6 páginasResearch Paper Gas Pricesafnhemzabfueaa100% (1)

- Research Paper Oil CompaniesDocumento8 páginasResearch Paper Oil Companiesfyrgevs3100% (1)

- Gas Prices Research PaperDocumento5 páginasGas Prices Research Paperafeaynwqz100% (1)

- Oil Prices Term PaperDocumento5 páginasOil Prices Term Papereeyjzkwgf100% (1)

- Delloite Oil and Gas Reality Check 2015 PDFDocumento32 páginasDelloite Oil and Gas Reality Check 2015 PDFAzik KunouAinda não há avaliações

- Building An Industry:: Can The United States Sustainably Export LNG at Competitive Prices?Documento18 páginasBuilding An Industry:: Can The United States Sustainably Export LNG at Competitive Prices?maiAinda não há avaliações

- Capturing Value in Global Gas LNGDocumento11 páginasCapturing Value in Global Gas LNGtinglesbyAinda não há avaliações

- The Liquefied Natural Gas IndustryDocumento24 páginasThe Liquefied Natural Gas IndustryRassoul NazeriAinda não há avaliações

- Us Oil and Gas Outlook 2018Documento8 páginasUs Oil and Gas Outlook 2018DebasishAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Statement About Oil and Gas PricesDocumento6 páginasThesis Statement About Oil and Gas Pricesgj9fmkqd100% (2)

- Shale Gas Boom Potential QuestionedDocumento12 páginasShale Gas Boom Potential QuestionedMartin GriffinAinda não há avaliações

- Energy Transition and PetrostateDocumento5 páginasEnergy Transition and PetrostateDanielAinda não há avaliações

- The Gas To Liquids Industry and Natural Gas MarketsDocumento13 páginasThe Gas To Liquids Industry and Natural Gas MarketsUJJWALAinda não há avaliações

- Absolute Return Letter Oil Price Target 0 Dollars by 2050 June 2017Documento6 páginasAbsolute Return Letter Oil Price Target 0 Dollars by 2050 June 2017freemind3682Ainda não há avaliações

- Hday R3 - Neg V Colleyville HeritageDocumento16 páginasHday R3 - Neg V Colleyville HeritageowenlgaoAinda não há avaliações

- 2015 Outlook On Oil and Gas:: My Take: by John EnglandDocumento4 páginas2015 Outlook On Oil and Gas:: My Take: by John EnglandsendarnabAinda não há avaliações

- WE ARE ON THE CUSP OF A GLOBAL ENERGY CRISISDocumento27 páginasWE ARE ON THE CUSP OF A GLOBAL ENERGY CRISISYog MehtaAinda não há avaliações

- Oilprice ArticleDocumento4 páginasOilprice ArticleGeorge OnyewuchiAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review On Oil PricesDocumento6 páginasLiterature Review On Oil Pricesjicjtjxgf100% (1)

- 3 Quarter Commentary: Abridged Summary: Arket OmmentaryDocumento24 páginas3 Quarter Commentary: Abridged Summary: Arket OmmentaryMatt EbrahimiAinda não há avaliações

- The Future of The Global Oil and Gas-1Documento34 páginasThe Future of The Global Oil and Gas-1georgiadisgAinda não há avaliações

- GenesisDocumento12 páginasGenesisGaurav SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Shale & Wall Street: Was The Decline in Natural Gas Prices Orchestrated?Documento32 páginasShale & Wall Street: Was The Decline in Natural Gas Prices Orchestrated?Energy Policy ForumAinda não há avaliações

- BP Peak Oil Demand and Long Run Oil PricesDocumento20 páginasBP Peak Oil Demand and Long Run Oil PricesKokil JainAinda não há avaliações

- Changes to Expect in the Oil & Gas IndustryDocumento10 páginasChanges to Expect in the Oil & Gas IndustryKrishnaAinda não há avaliações

- Shale Gas Hype or RealityDocumento46 páginasShale Gas Hype or Realityshyam_anupAinda não há avaliações

- Gas Shale 1Documento20 páginasGas Shale 1Jinhichi Molero RodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- 2015 Gea Insight ZmagsDocumento104 páginas2015 Gea Insight ZmagsArvind ShuklaAinda não há avaliações

- Hon Ian Macfarlane MP Shadow Minister For Energy and Resources Futuregas Conference - Brisbane 29-03-12Documento14 páginasHon Ian Macfarlane MP Shadow Minister For Energy and Resources Futuregas Conference - Brisbane 29-03-12api-95352340Ainda não há avaliações

- ExxonMobil Analysis ReportDocumento18 páginasExxonMobil Analysis Reportaaldrak100% (2)

- Oil Price DissertationDocumento7 páginasOil Price DissertationDoMyPaperForMeUK100% (1)

- Dissertation Oil PricesDocumento4 páginasDissertation Oil PricesDoMyCollegePaperForMeColumbia100% (1)

- 189 Getting Gas Right ReportDocumento49 páginas189 Getting Gas Right ReportaadhamAinda não há avaliações

- 2013 - 2 Shale Gas & Wall Street Debora RogersDocumento32 páginas2013 - 2 Shale Gas & Wall Street Debora RogersJoseLuis2013Ainda não há avaliações

- Thesis About Oil Price HikeDocumento8 páginasThesis About Oil Price Hikepamelacalusonewark100% (1)

- Hexa Research IncDocumento4 páginasHexa Research Incapi-293819200Ainda não há avaliações

- Oil Companies Research PaperDocumento6 páginasOil Companies Research Paperef71d9gw100% (1)

- PPI - Natural Gas Bridge To A Clean Energy Future - Alston 2003Documento7 páginasPPI - Natural Gas Bridge To A Clean Energy Future - Alston 2003ppiarchiveAinda não há avaliações

- U.S. Refining Trends - The Golden Age or The Eye of The Storm RB Part IDocumento12 páginasU.S. Refining Trends - The Golden Age or The Eye of The Storm RB Part INikolai OudalovAinda não há avaliações

- Worldenergyfocus 19 201601 PDFDocumento8 páginasWorldenergyfocus 19 201601 PDFSilvia TudorAinda não há avaliações

- BARCLAYS Global Energy OutlookDocumento154 páginasBARCLAYS Global Energy OutlookMiguelAinda não há avaliações

- The Oil & Gas Industry Doesn't Have A Bright Future The Oil & Gas Industry Volatile FutureDocumento2 páginasThe Oil & Gas Industry Doesn't Have A Bright Future The Oil & Gas Industry Volatile FutureRG MoPNGAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper Oil PricesDocumento5 páginasResearch Paper Oil Pricesfvfr9cg8100% (1)

- Statistical Energy PerspectiveDocumento9 páginasStatistical Energy PerspectiveJoel Diamante Gadayan Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Oil Price Research PaperDocumento7 páginasOil Price Research Paperlrqylwznd100% (1)

- 2.5. B-Energy AlternativesDocumento24 páginas2.5. B-Energy AlternativestwinkledreampoppiesAinda não há avaliações

- Peyto Exploration & Development Corp. President's Monthly ReportDocumento2 páginasPeyto Exploration & Development Corp. President's Monthly ReportCanadianValueAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper Over Gas PricesDocumento8 páginasResearch Paper Over Gas Pricesegwv92v7100% (1)

- Irrational Exuberance: Posted by Michael Doliner On February 12, 2020Documento5 páginasIrrational Exuberance: Posted by Michael Doliner On February 12, 2020Stephen BeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Compass Financial - Lincoln Anderson Commentary - Peak Oil - July 22, 2008Documento4 páginasCompass Financial - Lincoln Anderson Commentary - Peak Oil - July 22, 2008compassfinancialAinda não há avaliações

- Gas Price Research PaperDocumento5 páginasGas Price Research Papertug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Thesis Statement On Oil PricesDocumento8 páginasThesis Statement On Oil Pricesf5a1eam9100% (2)

- Oil and Gas Experts Debunk Common MythsDocumento3 páginasOil and Gas Experts Debunk Common MythsOmar RiveroAinda não há avaliações

- Component 1Documento11 páginasComponent 1Choki LhamoAinda não há avaliações

- Bertrand and Schoar, QJEDocumento41 páginasBertrand and Schoar, QJEdiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- NVR ExamplesDocumento4 páginasNVR ExamplesdiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- Tech StartupDocumento12 páginasTech StartupdiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- Roadmap Finalversion3Documento50 páginasRoadmap Finalversion3diponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- Biofuels Annual The Hague EU-27!8!13-2013Documento34 páginasBiofuels Annual The Hague EU-27!8!13-2013anandringsAinda não há avaliações

- Historical Fiction For Children in Grades 4 - 6: All Titles Are Located in The Juvenile Fiction SectionDocumento6 páginasHistorical Fiction For Children in Grades 4 - 6: All Titles Are Located in The Juvenile Fiction SectionPrajval PoojariAinda não há avaliações

- Bahadir, Bharadwaj, and Srivastava PDFDocumento17 páginasBahadir, Bharadwaj, and Srivastava PDFdiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- Grit JPSP PDFDocumento15 páginasGrit JPSP PDF'Mabel CardenasAinda não há avaliações

- Avoiding Decison TrapsDocumento4 páginasAvoiding Decison TrapsdiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- BellcurveDocumento5 páginasBellcurvediponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- b2b BrandingDocumento12 páginasb2b BrandingdiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- NGV Amsterdam Conference Brochure PDFDocumento8 páginasNGV Amsterdam Conference Brochure PDFdiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- BellcurveDocumento5 páginasBellcurvediponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- Diamond - Bright FutureDocumento4 páginasDiamond - Bright FuturediponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- Pricing HBRDocumento11 páginasPricing HBRMing DynastyAinda não há avaliações

- Roadmap To A Single European Transport Area White - Paper - Com (2011) - 144 - enDocumento31 páginasRoadmap To A Single European Transport Area White - Paper - Com (2011) - 144 - enRadu Victor TapuAinda não há avaliações

- Adblue - Material Data Safety Sheet: Management Solutions LTDDocumento4 páginasAdblue - Material Data Safety Sheet: Management Solutions LTDdiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- Clean Tech RevolutionDocumento2 páginasClean Tech RevolutiondiponogoroAinda não há avaliações

- 11 Baby Crochet Cocoon Patterns PDFDocumento39 páginas11 Baby Crochet Cocoon Patterns PDFIoanaAinda não há avaliações

- Is.4162.1.1985 Graduated PipettesDocumento23 páginasIs.4162.1.1985 Graduated PipettesBala MuruAinda não há avaliações

- Proceedings of The 16 TH WLCDocumento640 páginasProceedings of The 16 TH WLCSabrinaAinda não há avaliações

- Current Relays Under Current CSG140Documento2 páginasCurrent Relays Under Current CSG140Abdul BasitAinda não há avaliações

- LSUBL6432ADocumento4 páginasLSUBL6432ATotoxaHCAinda não há avaliações

- STS Chapter 1 ReviewerDocumento4 páginasSTS Chapter 1 ReviewerEunice AdagioAinda não há avaliações

- Are Hypomineralized Primary Molars and Canines Associated With Molar-Incisor HypomineralizationDocumento5 páginasAre Hypomineralized Primary Molars and Canines Associated With Molar-Incisor HypomineralizationDr Chevyndra100% (1)

- Placenta Previa Case Study: Adefuin, Jay Rovillos, Noemie MDocumento40 páginasPlacenta Previa Case Study: Adefuin, Jay Rovillos, Noemie MMikes CastroAinda não há avaliações

- WOOD Investor Presentation 3Q21Documento65 páginasWOOD Investor Presentation 3Q21Koko HadiwanaAinda não há avaliações

- Math 202: Di Fferential Equations: Course DescriptionDocumento2 páginasMath 202: Di Fferential Equations: Course DescriptionNyannue FlomoAinda não há avaliações

- ADIET Digital Image Processing Question BankDocumento7 páginasADIET Digital Image Processing Question BankAdarshAinda não há avaliações

- Tds G. Beslux Komplex Alfa II (25.10.19)Documento3 páginasTds G. Beslux Komplex Alfa II (25.10.19)Iulian BarbuAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Finite Element Methods (2001) (En) (489s)Documento489 páginasIntroduction To Finite Element Methods (2001) (En) (489s)green77parkAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Patents. 232467 - THE SYNERGISTIC MINERAL MIXTURE FOR INCREASING MILK YIELD IN CATTLEDocumento9 páginasIndian Patents. 232467 - THE SYNERGISTIC MINERAL MIXTURE FOR INCREASING MILK YIELD IN CATTLEHemlata LodhaAinda não há avaliações

- مقدمةDocumento5 páginasمقدمةMahmoud MadanyAinda não há avaliações

- 3D Area Clearance Strategies for Roughing ComponentsDocumento6 páginas3D Area Clearance Strategies for Roughing ComponentsMohamedHassanAinda não há avaliações

- Gas Natural Aplicacion Industria y OtrosDocumento319 páginasGas Natural Aplicacion Industria y OtrosLuis Eduardo LuceroAinda não há avaliações

- ProtectionDocumento160 páginasProtectionSuthep NgamlertleeAinda não há avaliações

- Features Integration of Differential Binomial: DX BX A X P N MDocumento4 páginasFeatures Integration of Differential Binomial: DX BX A X P N Mابو سامرAinda não há avaliações

- 11bg USB AdapterDocumento30 páginas11bg USB AdapterruddyhackerAinda não há avaliações

- Daftar Spesifikasi Teknis Pembangunan Gedung Kantor BPN BojonegoroDocumento6 páginasDaftar Spesifikasi Teknis Pembangunan Gedung Kantor BPN BojonegoroIrwin DarmansyahAinda não há avaliações

- Fundermax Exterior Technic 2011gb WebDocumento88 páginasFundermax Exterior Technic 2011gb WebarchpavlovicAinda não há avaliações

- Digital Communication QuestionsDocumento14 páginasDigital Communication QuestionsNilanjan BhattacharjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Clausius TheoremDocumento3 páginasClausius TheoremNitish KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Some Algal Filtrates and Chemical Inducers On Root-Rot Incidence of Faba BeanDocumento7 páginasEffect of Some Algal Filtrates and Chemical Inducers On Root-Rot Incidence of Faba BeanJuniper PublishersAinda não há avaliações

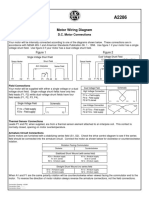

- Motor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor ConnectionsDocumento1 páginaMotor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor Connectionsczds6594Ainda não há avaliações

- Smart Note Taker Saves Time With Air WritingDocumento17 páginasSmart Note Taker Saves Time With Air WritingNagarjuna LokkuAinda não há avaliações

- SOIL ASSESSMENT AND PLANT PROPAGATION OF BELL PEPPERS (Capsicum Annuum)Documento35 páginasSOIL ASSESSMENT AND PLANT PROPAGATION OF BELL PEPPERS (Capsicum Annuum)Audrey Desiderio100% (1)

- TutorialDocumento324 páginasTutorialLuisAguilarAinda não há avaliações

- Artifact and Thingamy by David MitchellDocumento8 páginasArtifact and Thingamy by David MitchellPedro PriorAinda não há avaliações