Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Eyewitness Testimony

Enviado por

Fredy TolentoDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

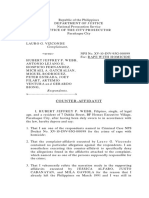

Eyewitness Testimony

Enviado por

Fredy TolentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Personality and Individual Differences 50 (2011) 559563

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Personality and Individual Differences

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/paid

Gender-related differences in eyewitness testimony

Igor Areh

Faculty of Criminal Justice and Security, University of Maribor, Kotnikova 8, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 14 September 2010

Received in revised form 29 October 2010

Accepted 25 November 2010

Available online 16 December 2010

Keywords:

Memory recall

Gender

Accuracy

Quantity

Eyewitness testimony

a b s t r a c t

The research focused on sex differences in the accuracy and quantity of memory recall for specic details

of an event. The respondent sample included 280 participants (57.5% females and 42.5% males) with an

average age of 19 years. The participants were shown a two-minute recording of a violent robbery, supposedly captured by a surveillance camera, and told their help was needed in verifying hypotheses for the

criminal investigation. The results have shown that, overall, females are more reliable eyewitnesses than

males. Most notably, females outperformed males in the accuracy of person descriptions, particularly in

victim descriptions. Males were more accurate in describing the event and also more condent in their

memory, especially when describing the place of the incident. However, male condence was unjustied

because females showed a higher degree of accuracy also in place descriptions. The quantity of recalled

details revealed no sex differences, probably because a checklist was used to evaluate memory recall.

2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Memory distortions affect the testimonies of criminal act

witnesses and represent a serious problem for at least two reasons

they have a bearing on the success rate in criminal act investigations and inuence court decisions. The scope of this issue was

underscored in 2000, when researchers found the number of

DNA exonerations for innocently convicted persons in the USA

and Canada to have been 118 up to that year (Scheck, Neueld, &

Dwyer, 2000). Ten years later, the number of false verdicts in the

USA alone has risen to 261 persons (Innocence Project, 2010). To

a large extent, false verdicts are the result of false testimony

(Scheck et al., 2000), and research has shown that legal professionals, police ofcers, and criminal investigators frequently have too

much faith in the accuracy of eyewitness testimony (Kebbell &

Milne, 1998; Lindsay, 2007).

Gender is one of the factors signicantly inuencing memory

recall, even though it has not yet been shown how great the differences are between the testimony of males and females, or what

those differences are (Wells & Olson, 2003). The overall opinion

is that small differences exist, and that they are due to differences

in specic cognitive abilities (Astur, Ortiz, & Sutherland, 1998;

Lippa, 2005).

In their inuential meta-analysis of a large number of face recognition studies, Shapiro and Penrod (1986) found that women

performed better in face recognition, but made more mistakes than

men. In order to explain this fact, they speculated that women

Tel.: +386 1 300 83 13; fax: +386 1 230 26 87.

E-mail address: igor.areh@fvv.uni-mb.si

0191-8869/$ - see front matter 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.11.027

have a greater desire for efciency and compliance with researchers than men. Recent research has conrmed that women are superior in face recognition (Rehnman & Herlitz, 2007). The differences

were especially pronounced for own-gender recognition in women, showing the existence of own-sex bias (Lewin & Herlitz,

2002; Wright & Sladden, 2003). Females also outperformed males

in recalling everyday tasks (Lindholm & Christianson, 1998), stories

(Zelinski, Gilewski, & Schaie, 1993), names (Herlitz, Nilsson, &

Bckman, 1997), and episodic memories (Herlitz & Rehnman,

2008; Tulving, 1983, 1993). Better episodic memory recall has

not only been conrmed in women, but also in children and young

adults (Marin, Holes, Guth, & Kovac, 1979), and the elderly (De

Frias, Nilsson, & Herlitz, 2006; Lindholm & Christianson, 1998).

Females outperform males in perceiving changes in familiar object

locations because they are better at recognizing object exchanges

and shifts, and novel objects conditions (Hassan & Rahman,

2007). In addition, females outperform males in spatial location

memory and object recognition (Eals & Silverman, 1994; Levy &

Astur, 2005). In fact, superior male performance has only been

demonstrated in spatial information memory, such as reading a

map (Loftus, Banaji, Schooler, & Foster, 1987). Females also outperform males when verbal content is used in memory recall tests

(Lewin, Wolgers, & Herlitz, 2001; Loftus et al., 1987). Gender differences are said to exist as a result of womens superior verbal abilities, which contribute to greater memory recall (Herlitz &

Rehnman, 2008). Research results for eyewitness testimony have

shown a female advantage in the number of details and accuracy

of memory recall, perhaps due to the theory that females have

more elaborate categories for person information (Lindholn &

Christianson, 1998).

560

I. Areh / Personality and Individual Differences 50 (2011) 559563

In addition to higher episodic memory recall, females also demonstrated higher autobiographical memory recall, especially if the

autobiographical memories had a strong emotional link (Seidlitz &

Diener, 1998). Emotional information is not always the reason

underlying accurate and lasting memories, however, as females

typically also recall more neutral memories than males (Bloise &

Johnson, 2007). Womens autobiographical memories are more detailed than mens (Davis, 1999; Seidlitz & Diener, 1998). A female

advantage in the accessibility and accuracy of autobiographical

memories is explained by two common hypotheses according

to the rst, womens perception of reality is more emotionally

charged, making their information encoding more effective (Fujita,

Diener, & Sandvik, 1991), and according to the second, a gender difference exists not only for encoding, but also for other two elementary memory processes: rehearsal, and retrieval of information

(Seidlitz & Diener, 1998).

More often than males, females would think about and discuss

emotionally charged events, which leads to the conclusion that females are more prone to rehearsing or processing emotionally

charged contents (Birditt & Fingerman, 2003; Harshman & Paivio,

1987; Schredl & Piel, 2003). Because a memory is strengthened

each time we consciously rehearse it or think about it, women tend

to be superior in recalling emotionally charged contents (Baddeley,

1997; Karpicke & Roediger, 2006), and tend to create emotionally

charged autobiographical memories (Loftus et al., 1987). This is

most probably also inuenced by a common belief that women

are more emotionally oriented than men, creating expectations

in participants and inuencing their responses in memory recall

tests (Loftus et al., 1987).

Differences in memory recall can also be attributed to different

levels of motivation, different expectations, and different experience. These factors all inuence where attention is directed and

how information is encoded into long-term memory (Colley, Ball,

Kirby, Harvey, & Vingelen, 2002; McGivern et al., 1997). Women

pay more attention to detail, for example to clothing (type of clothing, cut, and colour), to hair colour, hair length, hairstyle, and to

jewellery and make-up, which all contributes to more accurate

descriptions of persons (Loftus, 1996). Males outperform females

in recognizing male-oriented objects, but females outperform

males both in recognizing female-oriented objects and neutral objects (Loftus et al., 1987; McGivern et al., 1997; Powers, Andriks, &

Loftus, 1979). Evidence has shown superior female performance in

the recognition of female faces, most likely because women show

greater interest in the appearance of members of their own sex

(Horgan, Schmid-Mast, Hall, & Carter, 2004; Rehnman & Herlitz,

2007). Even though not all studies have conrmed gender differences in clothing descriptions (Yarmey, Jacob, & Porter, 2006),

the prevailing opinion is that women are better at describing the

external appearance of both sexes (Loftus, 1996).

The aim of the research was to establish gender differences in

memory recall when participants are asked to describe an event

they believe to be true. Several hypotheses were made: (1) accuracy of memory recall shows a female advantage, (2) females outperform males in the accuracy of person descriptions, (3) males are

as reliable as females in describing an event without person

descriptors, (4) females outperform males in the quantity of memory recall, and (5) males express a greater condence in their memory, especially in the details of the place of an incident.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The research included 280 rst-year undergraduate students

without prior theoretical knowledge on eyewitness accounts of

criminal acts. Out of the total, 161 (57.5%) participants were female

and 119 (42.5%) were male, with their ages ranging from 18 to

21 years (Me = 19). Their participation was voluntary.

2.2. Dependent variables

The accuracy and quantity of memory recall was established

with the following formulas:

P

P

P

AMR = Xtd/( Xatd + Xfd).

AMR: accuracy of memory recall.

P

X : sum of true details given by a participant.

P td

X : sum of all possible true details (constant value 85).

P atd

Xfd: sum of false details given by a participant.

P

P

P

QMR = ( Xtd + Xfd)/ Xd.

QMR: quantity of memory recall.

P

X : sum of true details given by a participant.

P td

X : sum of false details given by a participant.

P fd

Xd: sum of all details given in the checklist (constant

value 101).

2.3. Instrument

Memory recall was assessed using a feature checklist with a

break-down of visual and audio event details. The reason for using

a checklist was that in free recall, descriptions of persons tend to be

incomplete, which can either be the result of different criteria

about what is seen as important for each eyewitness (Koriat &

Goldsmith, 1996), or a result of vocabulary differences (Meissner,

Sporer, & Schooler, 2007). For the rst 20 items, participants had

to select among answers which dealt with the description of the

place of the incident, the objects in the place, and the incident itself. Participants selected the answer they believed was true; it

was also possible to answer with I dont know. Next, they were

given 28 person descriptors to describe the face, clothing, and

shoes of a man, followed by 29 person descriptors for a woman.

For each descriptor, they had to select one of six possible answers,

and were then given one point for a correct answer, zero points for

answering with I dont know, and 1 point for a false answer.

After the checklist, participants looked at several seven-level Likert

scales to assess the quality of their memories of the event, the man

and the woman, the location of the event, and their certainty in the

memory.

2.4. Material

A two-minute lm tape showing a violent robbery was made.

First a woman can be seen descending stairs and walking towards

an exit. Next, a man stops her in passing by and rst asks her to

lend him a small sum of money (5 euros), and then demands

the money from her. The woman keeps refusing, and the man becomes increasingly agitated. Failing to get what he is asking, the

man turns aggressive and physically assaults the woman, snatching her purse and running out of the building. The lm looks like

a recording made by a colour surveillance camera mounted on

the staircase ceiling.

2.5. Procedure

Participants watched the lm in small groups. Their viewing

schedule was planned so that students in different groups could

not meet each other and discuss the recording. At the beginning,

the participants were asked not to discuss the recording, which

they were told was real alleged authenticity of the recording

was supposed to provide additional motivation. The participants

were also told that the reason for watching the recording was to

561

I. Areh / Personality and Individual Differences 50 (2011) 559563

Table 1

Gender differences in memory recall of the event, in person descriptions, and in the accuracy and quantity of memory recall.

Variable

Sex

Meana(SD)

Accuracy of memory about the incident (no personal descriptors) true details

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

.56

.53

.58

.59

.21

.18

.49

.55

.29

.24

.65

.71

.50

.52

.74

.74

Memory recall of the man true details

Memory recall of the man false details

Memory recall of the woman true details

Memory recall of the woman false details

Memory about the place accuracy

Accuracy of memory recall (AMR)

Quantity of memory recall (QMR)

db

(.11)

(.11)

(.11)

(.13)

(.11)

(.09)

(.12)

(.13)

(.13)

(.12)

(.15)

(.15)

(.07)

(.08)

(.08)

(.09)

df

Sig.c

.27

2.02

278

.044

.08

1.00

278

.317

.30

1.96

220.86

.051

.48

3.91

278

.000

.40

3.15

278

.002

.40

3.04

278

.003

.27

2.40

278

.017

.00

.09

278

.925

Note: Men: N = 119; women: N = 161.

a

Proportions.

b

Cohens d.

c

Two-tailed.

Table 2

Gender differences for self-perceived accuracy in the memory of the incident, the victim, the assailant, and for the condence of the memory.

Variable

Sex

Mean (SD)

Memory of the incident (1 = no details, 7 = full of details)

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

3.38

3.25

3.55

3.61

3.78

3.78

4.64

4.25

4.32

4.05

Memory of the woman (1 = no details, 7 = full of details)

Memory of the man (1 = no details, 7 = full of details)

Memory of the place of the incident (1 = no details, 7 = full of details)

Condence in ones memory (1 = no conf., 7 = absolutely condent)

(1.37)

(1.14)

(1.29)

(1.26)

(1.30)

(1.25)

(1.24)

(1.31)

(1.16)

(1.12)

da

df

Sig.b

.10

.83

226.58

.133

.05

.39

278

.695

.00

.00

277

.999

.31

2.51

277

.013

.24

1.97

278

.050

Note: Men: N = 119; women: N = 161.

a

Cohens d.

b

Two-tailed.

help criminal investigators determine whether their assumptions

were correct. This was done in order to achieve higher ecological

validity of research results. We also assumed that participants

would be more motivated to take part in the research if they were

convinced the event was real. The participants lled out their

checklists one week after watching the recording.

3. Results

The reliability of the checklist was determined with Cronbachs

a, which was .63. Since the total number of items on the checklist

is high (N = 101), the low value of Cronbachs a can be explained

with the low variability of answers the participants were selecting from a limited number of possible answers.

Gender differences are most pronounced for victim description,

with females recalling signicantly more true details than males, a

nding supported by a medium effect size (d = .48). Somewhat

smaller but still signicant are gender differences for false details

of the victims appearance, with females reporting fewer false details than males (d = .40). Females also outperformed males in

place description.

Table 2 shows superior male condence in self-perceived accuracy in the memory of the place of the incident, indicated by a

moderate effect size (d = .31). Similarly, males expressed greater

self-perceived accuracy in the memory of the event.

4. Discussion

The rst hypothesis was that the accuracy of memory recall

would favour females over males; this turned out to be true. The

data for the accuracy of memory recall (Table 1) reveals that the

memory recall for females (AMR) is more accurate than for males.

The difference is small and corresponds with the results of other

researchers who came to similar conclusions in their eyewitness

account analyses (e.g. Lindholn & Christianson, 1998).

It was also assumed that females would outperform males in

the accuracy of memory recall connected with person descriptions.

Since females pay more attention to the personal appearance of

other people, their overall memory recall of events is more accurate than mens (Loftus, 1996). A female advantage in the overall

accuracy of memory recall could also have been inuenced by

the fact that 75% (57 out of 77) of the items from the checklist dealt

with the victims and the assailants appearance. If males lost

points here, it was impossible for them to make the difference up

over the 25% of remaining items which dealt with the incident

description. The proportion used between the quantity of person

descriptions and incident descriptions reects a real-life police

interview where investigators would mainly be concerned with

personal appearance. The results in Table 1 show that gender differences were the most apparent when participants were describing the victim and the assailant. Men gave fewer true details in

their memory recall of the victims appearance and more false

562

I. Areh / Personality and Individual Differences 50 (2011) 559563

details both for their description of the victim and of the assailant.

Females, therefore, were more accurate in their description of the

two subjects, which has also been shown by other researchers

(Horgan et al., 2004; Loftus, 1996; Rehnman & Herlitz, 2007). The

main reason for the differences in the accuracy of memory recall

was, it would seem, the description of the victim.

In their description of the victim, females gave more true, and

fewer false, details. Some researchers believe that females are better at describing members of their own sex because they pay more

attention to them (Loftus, 1996; McGivern et al., 1997). Another

possible reason why women focused on the victim more was that

they identied with her. The process of identication or empathy

with the victim probably started while the recording was being

watched, since the victim shares some characteristics with female

research participants: approximately the same age, a similar clothing style, and similar way of speaking. Since female participants

identied with the victim, they were probably more motivated to

take part in the research. They also believed that this was a real-life

event being investigated by criminal investigators, and were therefore more motivated that the perpetrator be caught and brought to

justice than men. Consequently, this kind of motivation can contribute to greater accuracy of memory recall.

Results in Table 1 shows a slight male advantage in incident

description, which is inconsistent with our hypothesis that there

are no gender differences in the accuracy of memory recall for

event description. This might mean that the difference between females and males in the accuracy of memory recall is prominent

only when it includes person descriptions. Without person descriptions, the difference is either smaller or non-existent, or, alternatively, males can be even more reliable than females. Information

relating to personal appearance is extremely important in criminal

investigations, and women have to be considered as slightly more

reliable eyewitnesses in this respect. We should not forget, however, that every eyewitness has to be thoroughly yet emphatically

interviewed in order for investigators to obtain useful information.

The fourth hypothesis proposed that females would outperform

males in the quantity of memory recall, but our results did not conrm this. In fact, the quantity of memory recall (Table 1) is practically the same for both sexes most likely due to the fact that

memory recall was limited to a checklist where participants could

not freely add the details they might have recalled. It is possible

that females noted details males did not, but these were not available in the given answers.

Males are more condent in assessing the reliability of their

memory (Table 2) because they are more condent in their memory than females; a nding which is consistent with other

researchers ndings (e.g. Yarmey, 1993). The difference between

genders is small, however, and if males are indeed more condent

in their memory there is little reason for them to be, since the accuracy of memory recall showed a female advantage. Further analysis

of Table 2 results reveals that males were more condent especially in their memory of the place of the incident, since they

assessed their memory as more detailed when compared to

females, which is what we expected. There were no signicant

differences between the sexes for self-perceived accuracy in the

memory of the victim, the assailant, and the incident. It was established that males were actually not more accurate in describing the

place of the incident (Table 1), but that, in fact, females were superior. The difference was to be expected since females outperform

males in perceiving changes and shifts in the scene (Hassan &

Rahman, 2007), in recalling object locations and in object recognition (Eals & Silverman, 1994; Levy & Astur, 2005).

The higher condence of males in their memory of the place of

the incident might be explained by the belief that males have better spatial ability than females, which could affect the condence

in their memory (Loftus et al., 1987). In assessing the accuracy of

their memory regarding the incident place, males might have been

more condent than females as a result of this belief; females were

more reserved in their judgment than males. The belief that males

are superior in recalling spatial information is, after all, relatively

wide-spread (Halpern, 2000; Loftus et al., 1987), and it is possible

that males overestimated and females underestimated the quality

of memory recall for the place of the incident as a result of this belief. The self-perceived gender differences are connected with the

way they are manifested in research results (Crawford, Chafn, &

Fitton, 1995; Hamilton, 1995). Gender differences in the accuracy

of total memory recall support the assumption that males overestimate the accuracy of their memory recall males are not as accurate, but nevertheless more condent than females.

Higher condence in the memory of the place of the incident,

which, it appears, signicantly contributed to overall higher condence in ones memory, is probably due to the fact that participants

watched the incident scene at the beginning of the recording for

approximately 10 s, during which time nothing else happened.

Afterwards there was intensive interpersonal dynamics, and the

participants focus shifted to the verbal and non-verbal action. Lower condence in the memory of the victim and the assailant is most

likely the result of a double attention focus when following the interpersonal dynamics. The event was fast and stress-inducing, leaving

the participants with a feeling that it was difcult to both see and

hear exactly what was happening and resulting in lower condence

in their memory, whereas the initial frame with the place of the incident gave them enough time to focus on place details.

5. Conclusion and limitations

When assessing eyewitness reliability in criminal and court cases,

it must be remembered that eyewitness condence levels can be

misleading. Males tend to express unjustiably greater condence,

making them seem more reliable and thus leading criminal investigators and judges to wrong conclusions. Females, on the other hand,

tend to be less condent than males, but with equally misleading

results the information they supply is often more accurate than

the information provided by males. Special attention should be paid

to gender-related differences for victims appearance; in this category, females outperformed males despite seeming less condent.

Nevertheless, caution should be exercised when applying these

ndings into practice. First of all, checklist reliability was only .63,

which means that error probability was 37%, and, second of all,

study results are based on mock crime testimonies. For an actual

event, the level of stress and the sense of being threatened might

just have inuenced gender-related differences.

The method of interviewing the participants was the main

weakness of our research and should be changed for the future.

Even though checklists have certain methodological advantages,

they restrict the variability of possible answers; if the memory

recall instrument had been less structured, ndings would have

broader implications. Recreating a criminal investigation interview

would also be sensible, since it would not have been as structured

as a checklist.

References

Astur, R. S., Ortiz, M. L., & Sutherland, R. J. (1998). A characterization of performance

by men and women in a virtual Morris water task: A large and reliable sex

difference. Behavioural Brain Research, 93, 185190.

Baddeley, A. D. (1997). Human memory: Theory and practice (Revised ed). Hove:

Psychology Press Ltd..

Birditt, K. S., & Fingerman, K. L. (2003). Age and gender differences in adults

descriptions of emotional reactions to interpersonal problems. Journal of

Gerontology, 58B(4), 237245.

Bloise, S. M., & Johnson, M. K. (2007). Memory for emotional and neutral

information: Gender and individual differences in emotional sensitivity.

Memory, 15(2), 192204.

I. Areh / Personality and Individual Differences 50 (2011) 559563

Colley, A., Ball, J., Kirby, N., Harvey, R., & Vingelen, I. (2002). Gender-linked

differences in everyday memory performance. Effort makes difference. Sex

Roles, 47, 577582.

Crawford, M., Chafn, R., & Fitton, L. (1995). Cognition in social context. Learning and

Individual Differences, 7(4), 341362.

Davis, P. J. (1999). Gender differences in autobiographical memory for childhood

emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3),

498510.

De Frias, C. M., Nilsson, L. G., & Herlitz, A. (2006). Sex differences in cognition are

stable over a ten-year period in adulthood and old age. Aging, Neuropsychology,

and Cognition, 13, 574587.

Eals, M., & Silverman, I. (1994). The hunter-gatherer theory of spatial sex

differences: Proximate factors mediating the female advantage in recall of

object arrays. Ethology and Sociobiology, 15, 95105.

Fujita, F. F., Diener, E., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Gender differences in negative affect and

well-being: The case for emotional intensity. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 61, 427434.

Halpern, D. F. (2000). Sex differences in cognitive abilities (3rd ed.). Hillsdale, NY:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hamilton, C. J. (1995). Beyond sex differences in visuo-spatial processing: The

impact of gender trait possession. British Journal of Psychology, 86, 120.

Harshman, R. A., & Paivio, A. (1987). Paradoxical sex differences in self-reported

imagery. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 41(3), 287302.

Hassan, B., & Rahman, Q. (2007). Selective sexual orientation-related differences in

object location memory. Behavioral Neuroscience, 121(3), 625633.

Herlitz, A., Nilsson, L.-G., & Bckman, L. (1997). Gender differences in episodic

memory. Memory and Cognition, 25(6), 801811.

Herlitz, A., & Rehnman, J. (2008). Sex differences in episodic memory. Current

Directions in Psychological Science, 17(1), 5256.

Horgan, T. G., Schmid-Mast, M., Hall, J. A., & Carter, J. D. (2004). Gender differences

in memory for the appearance of others. Personality and Social Psychology

Bulletin, 30(2), 185196.

Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. III, (2006). Repeated retrieval during learning is the

key to long-term retention. Journal of Memory and Language, 57(2), 151162.

Kebbell, M., & Milne, R. (1998). Police ofcers perception of eyewitness factors in

forensic investigations. Journal of Social Psychology, 138, 323330.

Koriat, A., & Goldsmith, M. (1996). Monitoring and control processes in the strategic

regulation of memory accuracy. Psychological Review, 103(3), 490517.

Levy, L. J., & Astur, R. S. (2005). Men and women differ in object memory but not

performance of a virtual radial maze. Behavioral Neuroscience, 119(4), 853862.

Lewin, C., & Herlitz, A. (2002). Sex differences in face recognition: Womens faces

make the difference. Brain and Cognition, 50, 121128.

Lewin, C., Wolgers, G., & Herlitz, A. (2001). Sex differences favoring women in verbal

but not in visuospatial episodic memory. Neuropsychology, 15, 165173.

Lindholm, T., & Christianson, S. . (1998). Gender effects in eyewitness accounts of a

violent crime. Psychology. Crime & Law, 4(4), 323339.

563

Lindsay, D. S. (2007). Autobiographical memory, eyewitness reports, and public

policy. Canadian Psychology, 48(2), 5766.

Lippa, R. A. (2005). Gender, nature, and nurture (2nd ed.). Mahwah, New Jersey:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Loftus, E. F. (1996). Eyewitness testimony. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University

Press.

Loftus, E. F., Banaji, M. R., Schooler, J. W., & Foster, R. (1987). Who remembers

what?: Gender differences in memory. Michigan Quarterly Review, 26, 6485.

Marin, B., Holes, D., Guth, M., & Kovac, P. (1979). The potential of children as

eyewitnesses: A comparison of children and adults on eyewitness tasks. Law

and Human Behavior, 3, 295306.

McGivern, R. F., Huston, J. P., Byrd, D., King, T., Siegle, G. J., & Reilly, J. (1997). Sex

differences in visual recognition memory: Support for a sex-related difference

in attention in adults and children. Brain and Cognition, 34(3), 323336.

Meissner, C. A., Sporer, S. L., & Schooler, J. W. (2007). Person descriptions as eyewitness

evidence. In R. Lindsay, D. Ross, J. Read, & M. Toglia (Eds.), Handbook of eyewitness

psychology: Memory for people (pp. 334). Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates.

Powers, P. A., Andriks, J. L., & Loftus, E. F. (1979). Eyewitness accounts of females and

males. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(3), 339347.

Rehnman, J., & Herlitz, A. (2007). Women remember more faces than men do. Acta

Psychologica, 124(3), 344355.

Scheck, B., Neueld, P., & Dywer, J. (2000). Actual innocence. New York: Doubleday.

Schredl, M., & Piel, E. (2003). Gender differences in dream recall: Data from four

representative German samples. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(5),

11851189.

Seidlitz, L., & Diener, E. (1998). Sex differences in the recall of affective experiences.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 262271.

Shapiro, P. N., & Penrod, S. (1986). Meta-analysis of facial identication studies.

Psychological Bulletin, 100(2), 139156.

Tulving, E. (1983). Elements of episodic memory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Tulving, E. (1993). Human memory. In P. Andersen, O. Hvalby, O. Paulsen, & B.

Hkfelt (Eds.), Memory concepts 1993: Basic and clinical aspects (pp. 2745).

Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Wells, G. L., & Olson, E. A. (2003). Eyewitness testimony. Annual Review of

Psychology, 54, 277295.

Wright, D. B., & Sladden, B. (2003). An own gender bias and the importance of hair in

face recognition. Acta Psychologica, 114, 101114.

Yarmey, A. D. (1993). Adult age and gender differences in eyewitness recall in eld

settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 19211932.

Yarmey, A. D., Jacob, J., & Porter, A. (2006). Person recall in eld settings. Journal of

Applied Social Psychology, 32(11), 23542367.

Zelinski, E. M., Gilewski, M. J., & Schaie, K. W. (1993). Individual differences in crosssectional and three-year longitudinal memory performance across the adult life

span. Psychology and Aging, 8(2), 176186.

Innocence Project (2010). Facts on Post-Conviction DNA Exonerations. Retrieved

October 28, 2010, from www.innocenceproject.org/know/

Você também pode gostar

- Fromm-Reichmann Transference ProblemsDocumento8 páginasFromm-Reichmann Transference ProblemsFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Who-statement-On-mental-health-promotion Fact Sheet Concepto de Salud MentalDocumento2 páginasWho-statement-On-mental-health-promotion Fact Sheet Concepto de Salud MentalFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- A Development of Freudian Metapsychology For Schisophrenia Artaloytia2014Documento26 páginasA Development of Freudian Metapsychology For Schisophrenia Artaloytia2014Fredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Barratt-2017-The International Journal of Psychoanalysis PDFDocumento15 páginasBarratt-2017-The International Journal of Psychoanalysis PDFFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) GuideDocumento18 páginasBrief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) GuideRoxana NicolauAinda não há avaliações

- The Psychoanlyst Ego and SuperegoDocumento22 páginasThe Psychoanlyst Ego and SuperegoFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- On Understanding Projective Identification in The Treatment of Psychotic States of The MindDocumento24 páginasOn Understanding Projective Identification in The Treatment of Psychotic States of The MindFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Hallucinations in The Psychothic State Psychoanalysis and Neurosciences ComparedDocumento26 páginasHallucinations in The Psychothic State Psychoanalysis and Neurosciences ComparedFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Hallucinations in The Psychothic State Psychoanalysis and Neurosciences ComparedDocumento26 páginasHallucinations in The Psychothic State Psychoanalysis and Neurosciences ComparedFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- On Understanding Projective Identification in The Treatment of Psychotic States of The MindDocumento24 páginasOn Understanding Projective Identification in The Treatment of Psychotic States of The MindFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- The Psychoanlyst Ego and SuperegoDocumento22 páginasThe Psychoanlyst Ego and SuperegoFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Kernberg 2014 TRASTORNOS NARCISISTASDocumento24 páginasKernberg 2014 TRASTORNOS NARCISISTASFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF PERSECUTORY Freeman2007 PDFDocumento33 páginasTHE PSYCHOLOGY OF PERSECUTORY Freeman2007 PDFFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Barratt-2017-The International Journal of Psychoanalysis PDFDocumento15 páginasBarratt-2017-The International Journal of Psychoanalysis PDFFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Multi AuditoryDocumento51 páginasMulti AuditoryFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 02Documento23 páginasChapter 02Fredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- McWilliamsschizoid Dynamics PDFDocumento31 páginasMcWilliamsschizoid Dynamics PDFFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- The Psychoanlyst Ego and SuperegoDocumento22 páginasThe Psychoanlyst Ego and SuperegoFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 03Documento25 páginasChapter 03Fredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Special Article: Words: Psycho-Oncology, Cancer, Multidisciplinary Treatment Approach, AttitudesDocumento16 páginasSpecial Article: Words: Psycho-Oncology, Cancer, Multidisciplinary Treatment Approach, AttitudeshopebaAinda não há avaliações

- Steiner Emergind From The Psychic Retreat PDFDocumento25 páginasSteiner Emergind From The Psychic Retreat PDFlc49100% (1)

- Barratt-2017-The International Journal of PsychoanalysisDocumento15 páginasBarratt-2017-The International Journal of PsychoanalysisFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Affect Biased AttentionDocumento8 páginasAffect Biased AttentionFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 03Documento25 páginasChapter 03Fredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- ATTENTION Training Children 1Documento8 páginasATTENTION Training Children 1Fredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- 12 Cases in Manic DepressiveDocumento231 páginas12 Cases in Manic DepressiveFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 01Documento14 páginasChapter 01Fredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- 12 Cases in Manic DepressiveDocumento231 páginas12 Cases in Manic DepressiveFredy TolentoAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- 8.3 Navarro v. Court of AppealsDocumento11 páginas8.3 Navarro v. Court of AppealsGlenn Robin FedillagaAinda não há avaliações

- Order Granting Motion For Summary Judgment - Brenda Powell v. Stephen GingerDocumento13 páginasOrder Granting Motion For Summary Judgment - Brenda Powell v. Stephen GingerAnonymous XetrNzAinda não há avaliações

- Appeals Court RulingDocumento26 páginasAppeals Court RulingMNCOOhioAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence ChartsDocumento115 páginasEvidence ChartsBrooke Henderson100% (1)

- Evidence Part 3 and 4Documento48 páginasEvidence Part 3 and 4Chedeng KumaAinda não há avaliações

- Stefanik/Turner Criminal Referral of Michael CohenDocumento4 páginasStefanik/Turner Criminal Referral of Michael CohenCami MondeauxAinda não há avaliações

- Obq Obli FinalDocumento97 páginasObq Obli FinalmjpjoreAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs MacaspacDocumento8 páginasPeople Vs MacaspacEricson Sarmiento Dela CruzAinda não há avaliações

- 1952 Madden Report (Original)Documento464 páginas1952 Madden Report (Original)adavielchiùAinda não há avaliações

- (No. L-1774. December 14, 1948) The People of The Philippines, Plaintiff and Appellee, vs. CLAUDIO ORDONIO, Defendant and AppellantDocumento12 páginas(No. L-1774. December 14, 1948) The People of The Philippines, Plaintiff and Appellee, vs. CLAUDIO ORDONIO, Defendant and AppellantMorphuesAinda não há avaliações

- CER L4 WS HighLifeLowLife AK PDFDocumento3 páginasCER L4 WS HighLifeLowLife AK PDFAlbertoGarsiaVenyverasAinda não há avaliações

- Aff. of Witness - Kimberly EstoleroDocumento2 páginasAff. of Witness - Kimberly EstoleroSteps RolsAinda não há avaliações

- Punjab Pharmacy Council application formDocumento2 páginasPunjab Pharmacy Council application formSalmanMaanAinda não há avaliações

- Digest PeopleVsHassanDocumento2 páginasDigest PeopleVsHassanJappy Alon100% (1)

- Judicial AffidavitDocumento6 páginasJudicial AffidavitJoseph Dimalanta Dajay100% (2)

- DJ files slander case against former producerDocumento3 páginasDJ files slander case against former producerJoan Pablo100% (2)

- Competency of A Witness, Competency of Accused, Accomplice, and SpouseDocumento2 páginasCompetency of A Witness, Competency of Accused, Accomplice, and SpouseArpit AgarwalAinda não há avaliações

- Ipc 698Documento4 páginasIpc 698sheel10% (2)

- Chiquita Julin Expert Report of FBI Agent Manuel OrtegaDocumento80 páginasChiquita Julin Expert Report of FBI Agent Manuel OrtegaPaulWolf100% (1)

- Lisa Lapointe Discriminates Against Terry Mallenby PTSD Disability PensionerDocumento77 páginasLisa Lapointe Discriminates Against Terry Mallenby PTSD Disability PensionerAdrian AnnanAinda não há avaliações

- J. Bernabe Case Digests Legal EthicsDocumento97 páginasJ. Bernabe Case Digests Legal EthicsKuyit MoAinda não há avaliações

- Monster Comprehension QuestionsDocumento4 páginasMonster Comprehension Questionskristyg16Ainda não há avaliações

- Unlawful Detainer Judicial AffidavitDocumento6 páginasUnlawful Detainer Judicial AffidavitNicole100% (1)

- JA AmbroseBUAzucenaDocumento3 páginasJA AmbroseBUAzucenaJosiah BalgosAinda não há avaliações

- Admin Case Procedure Against A TeacherDocumento1 páginaAdmin Case Procedure Against A Teachermina villamorAinda não há avaliações

- Michaella Surat Case: Officer Randal Klamser StatementDocumento100 páginasMichaella Surat Case: Officer Randal Klamser StatementMichael_Lee_RobertsAinda não há avaliações

- Annexure E1Documento1 páginaAnnexure E1Prabhat SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Crim Pro Cases Atty. DimayugaDocumento179 páginasCrim Pro Cases Atty. DimayugaVertine Paul Fernandez BelerAinda não há avaliações

- Compilation of Relevant Provisions of Special Criminal Laws: I. Book IDocumento68 páginasCompilation of Relevant Provisions of Special Criminal Laws: I. Book Ialyza burdeosAinda não há avaliações

- California Mediator Craig Kamansky Settled With Student Who Charged Him of Sex Crimes, and Teaching EthicsDocumento12 páginasCalifornia Mediator Craig Kamansky Settled With Student Who Charged Him of Sex Crimes, and Teaching EthicsA1newsnowAinda não há avaliações