Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: Docket Nos. 97-6293, 97-6333

Enviado por

Scribd Government DocsTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: Docket Nos. 97-6293, 97-6333

Enviado por

Scribd Government DocsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

169 F.

3d 136

83 A.F.T.R.2d 99-1040, 99-1 USTC P 50,298

UNITED STATES of America, Petitioner-Appellant-CrossAppellee,

v.

David A. ACKERT, Respondent-Appellee,

Paramount Communications, Inc. (now Viacom International,

Inc.), CPW Investments Ltd., CPW Holdings, Inc., Nieu

Oranjestad Partnership, Nieuw Oranjestad Partnership and

Maarten Investerings Partnership,

Intervenors-Defendants-Appellees-Cross-Appellants.

Docket Nos. 97-6293, 97-6333.

United States Court of Appeals,

Second Circuit.

Argued June 18, 1998.

Decided Feb. 26, 1999.

Kenneth W. Rosenberg, Washington, D.C. (Loretta C. Argrett, Assistant

Attorney General, Washington, D.C.; Charles E. Brookhart, Department

of Justice; John H. Durham, United States Attorney for the District of

Connecticut, Of Counsel), for Petitioner-Appellant-Cross-Appellee.

Maria T. Vullo, New York, NY (H. Christopher Boehning and Lavatus V.

Powell, III, Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, New York, NY,

Of Counsel), for Intervenors-Appellees-Cross-Appellants.

David H. Braff and Michael W. Martin, Sullivan & Cromwell, New York,

NY (On the Brief), for Respondent-Appellee.

Before: JACOBS and LEVAL, Circuit Judges, and MURTHA, Chief

District Judge.*

LEVAL, Circuit Judge:

The United States of America appeals from a decision of the district court

(William I. Garfinkel, Magistrate Judge ) in a tax summons enforcement

proceeding, barring the Internal Revenue Service from questioning Respondent

David A. Ackert, an investment banker, about his conversations with

Paramount Corporation's counsel, by reason of Paramount's attorney-client

privilege. We reverse.

BACKGROUND

2

The relevant facts are not in dispute. In 1989, Goldman, Sachs, and Co., an

investment banking firm, approached Paramount with an investment proposal.

The proposed transaction was expected to reduce Paramount's federal income

tax liability by generating significant capital losses that would offset

Paramount's recent capital gains from the sale of a subsidiary.

Ackert, at the time was employed by Goldman, Sachs. 1 Along with other

Goldman, Sachs representatives, Ackert pitched the investment proposal to

representatives of Paramount at an initial meeting on September 15, 1989.

After the September 15 meeting, Eugene I. Meyers, Paramount's senior vice

president and tax counsel, conducted legal research and analysis in order to

advise Paramount about the tax implications of the proposed investment. In the

course of this research, Meyers contacted Ackert, and the two men had several

follow-up meetings to discuss various aspects of the Goldman, Sachs proposal.

Meyers initiated these discussions to learn more about the details of the

proposed transaction and its potential tax consequences, so that he could advise

his client, Paramount, about the legal and financial implications of the

transaction.

Paramount ultimately decided to enter into the proposed investment, but used

the services of another investment banker, Merrill Lynch & Co. Paramount paid

Goldman, Sachs a fee of $1.5 million for services rendered in connection with

its proposal.

Seven years later, in 1996, the Internal Revenue Service was conducting an

audit of Paramount and its subsidiaries for its 1989 through 1992 tax years. In

connection with the audit, the IRS issued a summons to Ackert seeking his

testimony about the 1989 investment proposal. Paramount asserted the

attorney-client privilege with respect to questions concerning any conversations

Ackert had with Meyers or in Meyers' presence.

The United States filed suit in the district court, seeking to enforce the

The United States filed suit in the district court, seeking to enforce the

summons through an order directing Ackert to appear before the IRS and

answer its questions. By consent of the parties, the petition was referred to

Magistrate Judge Garfinkel. Paramount intervened.

The magistrate judge granted the petition to enforce the IRS summons, but

initially deferred ruling on the attorney-client privilege. The IRS agreed to

question Ackert about the allegedly privileged communications in the

magistrate's courtroom, so that Paramount could assert its objections and the

judge could rule on them contemporaneously. Paramount objected to questions

about the conversations between Ackert and Meyers subsequent to the initial

September 15, 1989, meeting. The magistrate judge heard argument from

Paramount and the United States, and conducted an in camera interview with

Ackert about the substance of these conversations.

Following the in camera proceedings, the magistrate judge ruled in favor of

Paramount, concluding that the government's inquiry into the Ackert-Meyers

conversations "would invade privileged communications." The United States

appeals from this ruling. Paramount also appeals from the order that enforced

the summons directing Ackert's appearance.

10

The magistrate judge said little in explanation of his ruling, but had indicated

earlier that if Meyers had been collecting information from Ackert about the

proposed investment in order to give legal advice to Paramount, the

conversations would be privileged. We understand that to be the basis of his

ruling.

DISCUSSION

11

Recognizing that the attorney-client privilege generally applies only to

communications between the attorney and the client, and that Ackert was not

Meyers's client, Paramount seeks to justify its assertion of the privilege by

reference to Judge Friendly's opinion in United States v. Kovel, 296 F.2d 918

(2d Cir.1961). Kovel held that the privilege can protect communications

between a client and his accountant, or the accountant and the client's attorney,

when the accountant's role is to clarify communications between attorney and

client. See id. at 922. If a client and attorney speak different languages, an

interpreter could help the attorney understand the client's communications

without destroying the privilege. Kovel recognized that an accountant can play

a role analogous to an interpreter in helping the attorney understand financial

information passed to the attorney by the client. Id.

12

Paramount contends that the Ackert-Meyers conversations mirror the

accountant-attorney relationship described in Kovel. Paramount emphasizes

that Meyers contacted Ackert seeking information about the details of the

proposed investment for the sole purpose of providing legal advice to

Paramount. It asserts that "it was impossible for Mr. Meyers to advise

Paramount without these further contacts with Mr. Ackert, because he could

not otherwise fully define the factual, and therefore legal, nature of the

proposal." Paramount Br. at 21.

13

We respectfully disagree with both the magistrate judge's explanation for his

ruling and with the argument offered by Paramount on appeal in support of the

ruling.

14

We assume, as did the magistrate judge, that Meyers interviewed Ackert in

order to gain information and to better advise his client Paramount. That,

however, is insufficient to give rise to the privilege. The purpose of the

privilege is "to encourage clients to make full disclosure to their attorneys."

Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391, 403, 96 S.Ct. 1569, 48 L.Ed.2d 39

(1976). To that end, the privilege protects communications between a client

and an attorney, not communications that prove important to an attorney's legal

advice to a client. Thus, a communication between an attorney and client may

be privileged even if it turns out to be unimportant to the legal services

provided. See 8 Wigmore on Evidence 2292, at 554 (McNaughton rev.

ed.1961)(listing essential elements of privilege); Scott N. Stone & Robert K.

Taylor, 1 Testimonial Privileges 1.24-1.35 (2d ed.1995) (discussing scope of

privilege). Conversely, a communication between an attorney and a third party

does not become shielded by the attorney-client privilege solely because the

communication proves important to the attorney's ability to represent the client.

See Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U.S. 495, 508, 67 S.Ct. 385, 91 L.Ed. 451 (1947);

Colton v. United States, 306 F.2d 633, 639 (2d Cir.1962); 8 Wigmore on

Evidence 2317 at 619 ("It is ... not sufficient for the attorney, in invoking the

privilege, to state that the information came somehow to him while acting for

the client nor that it came from some particular third person for the benefit of

the client.") (emphasis omitted). Accordingly, we reject the magistrate judge's

explanation for extending Paramount's privilege to conversations between its

counsel and an independent investment banker, notwithstanding our assumption

that those conversations significantly assisted the attorney in giving his client

legal advice about its tax situation.

15

We also reject Paramount's argument based on Kovel. That decision recognized

that the inclusion of a third party in attorney-client communications does not

destroy the privilege if the purpose of the third party's participation is to

improve the comprehension of the communications between attorney and

client. That principle, however, has no application to this case. Meyers was not

relying on Ackert to translate or interpret information given to Meyers by his

client. Rather, Meyers sought out Ackert for information Paramount did not

have about the proposed transaction and its tax consequences. Because Ackert's

role was not as a translator or interpreter of client communications, the

principle of Kovel does not shield his discussions with Meyers. We therefore

find that Paramount has failed to demonstrate a basis for asserting its attorneyclient privilege based on Meyers's communications with Ackert.

16

We do not preclude the possibility that, as the examination of Ackert proceeds,

Paramount might demonstrate circumstances bringing some particular question

or questions put to Ackert within the scope of Paramount's privilege. But we

reject the magistrate judge's broad ruling that the entire examination of Ackert

on his communications with Meyers is protected by Paramount's privilege.

17

We find no merit in Paramount's cross-appeal from the district court's order

enforcing the summons.

CONCLUSION

18

We affirm the magistrate judge's ruling granting enforcement of the IRS

summons directed to Ackert. We reverse the ruling that questions put to Ackert

concerning his communications with Meyers invade Paramount's attorneyclient privilege.

The Honorable J. Garvan Murtha, Chief District Judge of the United States

District Court for the District of Vermont, sitting by designation

Although Ackert is an attorney, he functioned solely as an investment banker

while at Goldman, Sachs. Although he discussed the possible tax consequences

of investments with potential clients, including Paramount, he did not provide

them with legal or tax advice

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento20 páginasUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento7 páginasCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento2 páginasGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento21 páginasCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento8 páginasPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento22 páginasConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento15 páginasApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento100 páginasHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento6 páginasBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento50 páginasUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento10 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento14 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento9 páginasNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento24 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento10 páginasNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento18 páginasWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento15 páginasUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento17 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento27 páginasUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento2 páginasUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento7 páginasUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- NJ Debt Collection LawsDocumento10 páginasNJ Debt Collection LawsfdarteeAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Procedure Code 1908 NotesDocumento23 páginasCivil Procedure Code 1908 NotesAbhilash Aggarwal100% (2)

- Jose Vs BoyonDocumento5 páginasJose Vs BoyonWeng CuevillasAinda não há avaliações

- Motion To Declare Defendant in DefaultDocumento3 páginasMotion To Declare Defendant in DefaultMagtanggol HinirangAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Motion To Quash Service For California Under Code of Civil Procedure Section 418 10Documento4 páginasSample Motion To Quash Service For California Under Code of Civil Procedure Section 418 10christina giangola100% (1)

- Municode 16-44 Juvenile CurfewDocumento3 páginasMunicode 16-44 Juvenile CurfewThe Brookhaven PostAinda não há avaliações

- Ruling of The Court of AppealsDocumento3 páginasRuling of The Court of AppealsMarx Earvin TorinoAinda não há avaliações

- Child Support Collection LetterDocumento9 páginasChild Support Collection LetterSLAVEFATHER100% (4)

- County Court Civil Procedure Rules 2008Documento643 páginasCounty Court Civil Procedure Rules 2008Bek GrouiosAinda não há avaliações

- CivPro Riano SummarizedDocumento181 páginasCivPro Riano SummarizedKoko91% (11)

- Declaratory Judgment PacketDocumento19 páginasDeclaratory Judgment PacketMW100% (1)

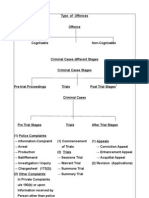

- Chart of Criminal Proceedings in IndiaDocumento11 páginasChart of Criminal Proceedings in IndiaPatel Tejas43% (7)

- Les 10 17.melaiDocumento17 páginasLes 10 17.melaimelaniem_1Ainda não há avaliações

- TABLE-SPECIAL CIVIL ACTIONS - And-Special-RulesDocumento42 páginasTABLE-SPECIAL CIVIL ACTIONS - And-Special-RulesErikha AranetaAinda não há avaliações

- 162010-2008-Banco de Oro-EPCI Inc. v. JAPRL Development20170517-911-14vqr8lDocumento10 páginas162010-2008-Banco de Oro-EPCI Inc. v. JAPRL Development20170517-911-14vqr8lLex LearnAinda não há avaliações

- Metrobank v. CustodioDocumento3 páginasMetrobank v. CustodioKarla Lois de GuzmanAinda não há avaliações

- Defendants' Opposition To Malibu Media, LLC's 3rd Motion For An Extension of Time To Serve ProcessDocumento9 páginasDefendants' Opposition To Malibu Media, LLC's 3rd Motion For An Extension of Time To Serve ProcessBilly WohlsiferAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction - : Summons Should Be Accompanied by The PlaintDocumento6 páginasIntroduction - : Summons Should Be Accompanied by The PlaintShivansh shuklaAinda não há avaliações

- Drafting New 2Documento253 páginasDrafting New 2Ishan SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Bibliotechnical Athenaeum v. National Lawyers Guild - Summons and ComplaintDocumento7 páginasBibliotechnical Athenaeum v. National Lawyers Guild - Summons and ComplaintLegal InsurrectionAinda não há avaliações

- Processes To Compel Attendance of An Offender Before A CourtDocumento6 páginasProcesses To Compel Attendance of An Offender Before A CourtABDOULIEAinda não há avaliações

- Orange County Eviction BrochureDocumento2 páginasOrange County Eviction BrochureWendy AlejoAinda não há avaliações

- Application For Revision From The ProceedingsDocumento20 páginasApplication For Revision From The ProceedingsMwambanga Mīkhā'ēlAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment: Topic: - Summon in Civil SuitDocumento12 páginasAssignment: Topic: - Summon in Civil SuitMohammad Ziya AnsariAinda não há avaliações

- Pontenciano v. BarnesDocumento3 páginasPontenciano v. BarnesKevin HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Civilprocedure (With 20 General Civil Forms Oh)Documento434 páginasCivilprocedure (With 20 General Civil Forms Oh)cjAinda não há avaliações

- Aamodt ComplaintDocumento7 páginasAamodt ComplaintPatch MinnesotaAinda não há avaliações

- Ma. Teresa Chaves Biaco, Petitioner, vs. Philippine Countryside Rural BankDocumento2 páginasMa. Teresa Chaves Biaco, Petitioner, vs. Philippine Countryside Rural BankArtemisTzy100% (2)

- Valmonte V CADocumento12 páginasValmonte V CAAsHervea AbanteAinda não há avaliações

- ADGMCFI2021021 Samer Yasser Hilal V Haircare LTD Judgment of Justice Sir Michael Burton GBE 070120Documento8 páginasADGMCFI2021021 Samer Yasser Hilal V Haircare LTD Judgment of Justice Sir Michael Burton GBE 070120abdeali hazariAinda não há avaliações

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNo EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (26)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearNo EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (559)

- Maktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistNo EverandMaktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesNo EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1635)

- Power Moves: Ignite Your Confidence and Become a ForceNo EverandPower Moves: Ignite Your Confidence and Become a ForceAinda não há avaliações

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNo EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (6)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNo EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (80)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentNo EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (4125)