Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

ANCA Lab Audit

Enviado por

akshatvishiDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

ANCA Lab Audit

Enviado por

akshatvishiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2016

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) testing: Audit

from a clinical immunology laboratory

Sanat PHATAK, Amita AGGARWAL, Vikas AGARWAL, Able LAWRENCE and Ramnath MISRA

Department of Clinical Immunology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, India

Abstract

Aim: Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are associated with small vessel vasculitis now termed

ANCA associated vasculitis (AAV). ANCAs are reported in diverse diseases where they have no clinical utility.

We carried out an audit in a clinical immunology laboratory and assessed if use of ordering practices could have

improved utility of ANCA.

Methods: All samples received for ANCA testing during 2014 were tested by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF)

and automated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Clinical records of all samples positive by one or

more assays were retrieved. We assessed the effect of applying proposed test ordering guidelines on performance

of the tests.

Results: Of 1590 samples, 108 (6.8%) had a positive result by at least one method. IIF showed perinuclear pattern in 72 (21 were antinuclear antibody positive), cytoplasmic in 22, six had atypical pattern and eight were

negative. By ELISA anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies were present in 33 samples, anti-proteinase 3 in 24, while

five sera had both antibodies. ELISA and IIF were concordant in 45 samples. Twenty-seven patients had AAV of

which 23 were both ELISA and IIF positive. Among these 27 with AAV all had at least one ordering criteria, while

in 81 patients without AAV but with positive test, 38 had no ordering criteria.

Conclusion: Reduction in false positive can be achieved by considering only those samples as ANCA positive

that test positive both on IIF and ELISA and by following ordering guidelines before requesting ANCA testing,

and by use of ordering criteria by clinicians.

Key words: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, ordering practices, vasculitis.

INTRODUCTION

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), following their description in 1982, have come into clinical use

widely, mainly in the diagnosis of a group of vasculitides

encompassing granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA),

microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) and renal limited

pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis.1 Owing

Correspondence: Professor Amita Aggarwal, Department of

Clinical Immunology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of

Medical Sciences, Raebareilly road, Lucknow 226014, India.

Email: aa.amita@gmail.com

to the similarities in clinical features, histopathology and

the presence of ANCA, this group of diseases have been

duly named ANCA associated vasculitis (AAV) and this

was upheld by the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Criteria

Guidelines.2 ANCA has been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity for AAV.3 Inflammatory bowel

disease (especially ulcerative colitis) and autoimmune

liver diseases are known to have ANCA due to antigens

apart from proteinase 3 (PR3) and myeloperoxidase

(MPO).4,5 Numerous other conditions, including

rheumatoid arthritis (RA), tuberculosis and leprosy, can

also have ANCA positivity. In these diseases, the test

does not have diagnostic utility and is frequently a

source of confusion rather than clarity.

2016 Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology and John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

S. Phatak et al.

Two methods of performing ANCA form the backbone of ANCA testing: indirect immunofluorescence

(IIF) on ethanol-fixed human neutrophils, and assays

to demonstrate binding specificities to relevant neutrophil antigens, namely the neutrophil serine protease

PR3 and MPO. Assays for the latter include enzymelinked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), lateral flow

assays (LFA), chemiluminescent assays (CLA) and

microbead assays. The International Consensus Statement Guidelines (1999) and a further addendum recommend a two -step approach: IIF as initial screening

with confirmation using a solid phase assay like

ELISA.6,7 The combination of both methods provides a

high specificity of 99% for AAV without compromising

on sensitivity.8

In a resource-limited setting such as India, many laboratories do not have the availability of both tests. Subsequently, patients are frequently brought to clinical

attention when only one of the tests is positive. Some

authors have even suggested doing away with IIF.9 To

parallel this testing practice, we considered the presence

of either IIF or ELISA to mean a positive result in our

analysis.

The diagnostic usefulness of a test depends not only

on the performance characteristic of the test but also

the patient population being studied. The application

of test ordering guidelines is an exercise in increasing

the pre-test probability of the disease by selection of

those who are clinically more likely to have the disease,

thus improving the positive predictive value (PPV). This

was the rationale behind the development of test ordering guidelines for ANCA.8 We retrospectively analyzed

the fulfillment of these guidelines in our population.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We reviewed laboratory records for all blood samples

testing positive for ANCA, by immunofluorescence,

ELISA or both in the span of 1 year, from 1 January to

31 December 2014. Clinical records of these patients

were later retrieved from the hospital information system, and outpatient notes, discharge summaries and

other investigation parameters were viewed. The diagnoses of the patients were taken as per the treating diagnoses of the managing clinicians who were contacted in

circumstances of doubt. To find patients apart from

these who were diagnosed as AAV, a search of the hospital information system was carried out using the

terms ANCA-associated vasculitis, GPA (or Wegeners

granulomatosis), EGPA (or Churg-Strauss syndrome),

MPA, renal limited vasculitis and pauci-immune

glomerulonephritis. Patients who carried a diagnosis of

ANCA-associated vasculitis were labeled as AAV only if

they fulfilled classification criteria (American College of

Rheumatology criteria for GPA and EGPA; Chapel Hill

consensus criteria for MPA). Patients with disease limited to the kidney, proven to have pauci-immune or crescentic glomerulonephritis were classified as renal limited

vasculitis. If more than one ANCA test were ordered during the year for a single patient, the initial test was considered. Patients with rapidly progressive nephritis who

had both ANCA and anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibodies positive were considered

to have anti-GBM disease and had been treated as such.

All samples for ANCA testing were only from patients

treated at a single hospital in various departments,

either hospitalized or on an outpatient basis. ANCA

testing was performed both by immunofluorescence

and ELISA for anti-PR3 and anti-MPO. Immunofluorescence patterns were reported by one of four faculty

members in clinical immunology. In the event of a

doubt, the results were seen independently by two other

faculty members and reported only if a consensus was

reached. Anti-PR3 and anti-MPO antibodies were done

by automated ELISA system (Cobas, Germany). A cutoff of 30 Arbitrary units (AU) was considered as a positive test. Patients records were checked to determine

whether they fulfilled test-ordering guidelines as given

by Hagen et al.8

RESULTS

During the span of 1 year, the laboratory received 1590

blood samples for ANCA testing. One hundred and eight

samples (6.79%) tested positive by at least one method.

IIF was positive in 100 samples (6.28%). A perinuclear pattern was seen in 72, cytoplasmic pattern in 22

and six had an atypical pattern. ELISA was positive in

53 patients. Anti-MPO antibodies were present in 34

samples, anti-PR3 antibodies were present in 24 samples, whereas five samples tested positive for both antibodies. Forty-five samples showed concordance

between the IIF and ELISA results, eight samples were

positive only by ELISA, while 55 were positive only by

IIF. Reviewing hospital records of the patients with positive test results on their samples revealed that 27

patients (1.6%) had AAV. All patients fulfilled the criteria for diagnosis of AAV. No patient had AAV among

those testing negative for ANCA.

Taking ANCA positivity as positivity by either IIF or

ELISA, the sensitivity of the test was 100%, the specificity was 96% while the positive predictive value (PPV)

International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2016

Audit of ANCA testing

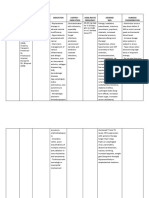

Table 1 Salient diagnoses among 87 patients with positive ANCA, not having ANCA vasculitis

Diagnosis

No.

ANCA-IIF

ELISA

Renal failure, other causes

22

p-ANCA: 12

c-ANCA: 5

a-ANCA: 4

p-ANCA: 5

c-ANCA: 4

p-ANCA: 5

c-ANCA: 1

p-ANCA: 10

p-ANCA: 6

c-ANCA: 2

a-ANCA: 1

p-ANCA: 3

p-ANCA: 2

c-ANCA: 1

PR3: 4

MPO: 4

Rheumatoid arthritis

IBD (UC)

SLE

ILD

Malignancy

Tuberculosis

10

10

5

5

MPO: 2

PR3: 1

Observations

Most had CKD, no cause found

3 had anti-GBM disease

2 had IgA nephropathy

3 had vasculitis (2 skin ulcers, 1 neuropathy)

2 had liver cirrhosis

MPO: 3

MPO: 4

PR3: 1

All had homogenous ANA. 5 had lupus nephritis

3 had multiple autoantibodies

MPO: 1

MPO: 1

PR3: 1

Ovary, breast, prostate

2 had arthritis, 1 had renal failure

a, atypical; anti-GBM, anti-glomerular basement membrane; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; c, cytoplasmic; CKD, chronic kidney

disease; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; MPO, myeloperoxidase; p, perinuclear; PR3, proteinase 3.

was 33.3% for a diagnosis of AAV. If ANCA positivity

was defined as positivity on both IIF and ELISA, the

sensitivity dropped to 85.18%, while specificity and

PPV increased to 98.5 and 51.1%, respectively.

In the AAV group, renal involvement was the most

common presentation in 18 patients (66%). Breathlessness was the most common symptom (16 patients,

59.2%), while hypertension was the most common sign

(20 patients, 74%). Lower respiratory involvement was

present in 13 (48%) while six (22%) had upper respiratory tract involvement. Fever, peripheral neuropathy

and arthritis were present in 11 (40%), four (14%) and

four (14%), respectively. Other presenting complaints

included digital gangrene, scleritis and retinal vasculitis.

Seventeen patients had multisystem involvement and

fit in the classic vasculitides: nine patients with GPA,

seven patients with MPA and one with EGPA. Thirteen

of these were newly diagnosed during the period of the

study while four were known patients tested due to suspected relapse (three patients) and for response to treatment (one patient). Diagnostic biopsies were done in

eight of these patients, including five kidney biopsies,

two nerve biopsies and one skin biopsy. Ten patients

had renal limited disease; all of them presented with

rapidly progressive renal failure and all had evidence of

nephritic sediment at the time of diagnosis. Renal

biopsy demonstrated pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis in six, and diffuse glomerulosclerosis in one

among seven patients in whom it was performed.

Eighty-one patients had positive ANCA results by at

least one method but did not have AAV. Twenty-two

samples (27.1%) showed concordance by both tests.

International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2016

Salient diagnoses among these included renal failure of

other causes, systemic lupus erythematosus, interstitial

lung disease and inflammatory bowel disease (Table 1).

Analyzing if the patients who had a positive result had

any of the features suggestive of ANCA-associated disease

as suggested by Hagen et al.8, 70 patients with positive

ANCA (64%) had at least one feature. The most common feature was rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis,

while no patient had upper airway erosive disease, subglottic or tracheal stenosis or retro-orbital mass.

Among 27 AAV patients, all fulfilled at least one criteria, nine fulfilled two, two patients fulfilled three, while

one fulfilled four criteria. Out of the 81 patients without AAV, 38 (46%) did not fulfill even a single criterion, 37 fulfilled one and six fulfilled two ordering

criteria. Had criteria been followed strictly, the false

positive rate would have been reduced from 75% to

62%. No case of AAV would have been missed.

DISCUSSION

ANCA has achieved widespread use among clinicians

across specialties, due to heterogeneous presentations

of the AAVs. However, clinicians need to realize that

rational ordering is needed to avoid red herrings. Our

data suggest that despite good sensitivity of ANCA for

diagnosis of AAV, the PPV of a positive test is low and it

improves to about 50% if the sample is positive by both

ELISA and IIF. Use of ordering guidelines led to reduction in false positive rates by 25%.

Sensitivity of ANCA in a European multicenter

study was 8185%.8 Our sensitivity was much higher,

S. Phatak et al.

probably due to referral bias to a tertiary care hospital

where patients having generalized disease get referred,

also supported by lack of isolated upper airway disease

in any patient in this group. Segelmark et al. have suggested that with a high sensitivity, ANCA is an attractive

candidate for a screening test; however, other studies

have questioned its utility as such.10,11

The overall positivity for ANCA of 6.7% among more

than 1500 samples tested in this study is similar to data

from other clinical immunology laboratories: 13% at a

hospital in Southampton, UK had a positive ANCA by

IIF. Stone et al.12 studied 856 ANCA samples at Johns

Hopkins University and found that 8% had AAV. Positivity rate of ANCA may vary by the department ordering the test.13

PPV of 33% with one test and 51% with two tests

compares well with previous studies. Two other studies

have found PPVs of 45% (IIF alone) and 54%, respectively.12,14 Various factors have been shown to influence PPV. PPV increased from 59% to 79% using IIF

and ELISA compared to IIF alone.15 Due to consistently

low PPV values, tissue demonstration of vasculitis on

biopsy specimens still remains the gold standard in the

diagnosis of AAV.

The current strategy of only taking tests positive by

both assays avoids misdiagnoses and increases specificity.7,15 In a resource-limited setting like India, many

clinicians order only one, commonly IIF, to reduce

patient costs. Stone et al.12 demonstrated that specificity

improved from 93% to 99% and PPV from 45% to

88% using a combined IIF/ELISA approach as compared to IIF alone. A meta-analysis of combined ANCA

testing shows an overall sensitivity of 82% and an overall specificity of 99%.16 Thus we recommend combined

testing, even in a resource-limited setting, as false positives are more likely to lead on to further investigations

which in turn will also increase costs.

Similar to our data, ANCA positivity has been

reported in conditions apart from AAV. Nearly onethird of RA patients had ANCA by IIF,17 and a few also

had anti-MPO antibodies.18 In contrast, most of the

SLE sera showed perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) staining

due to antinuclear antibodies (ANA) on ethanol-fixed

smears and only one had low-titer anti-PR3 antibodies.

ANA and p-ANCA resemble each other closely, and are

difficult to differentiate. It is likely that the positive

ANCA on IIF was in fact ANA and underscores the

importance of performing ANA in patients in relevant

clinical situations.

ANCA occurs in chronic infections such as tuberculosis and leprosy.19,20 Studies have shown prevalence in

tuberculosis of 3044% on IIF.21,22 However, other

studies have documented a complete absence of ANCA

by both methods.23 This discrepancy may be due to differences in ethnic backgrounds, strains of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis or lack of laboratory standardization.24 All

the tuberculosis cases in our study were microbiologically proven and thus it is an important cause of false

positive ANCA, especially in endemic areas such as

India, due to a similar presentation with cavitating pulmonary nodules and divergent treatments.

If the test is ordered indiscriminately in patients with

low pre-test probability, a large number of false

positive results are expected. This leads to diagnostic

confusion, and unnecessary invasive testing and

immunosuppression, increasing patient morbidity and

healthcare costs. The effect of application of a gating

policy of clinical indications prior to ANCA reduced

the ANCA false positive rate by 27.14 Utilizing slightly

different ordering criteria, Arnold et al.25 studied the

effects of enforcing a gating policy to ordering ANCA

over sequential years, and found a 12% rise in positivity rate. While no cases of AAV were missed in these

two studies, in an earlier study the application of a gating strategy led to missing one case of AAV.26 Our

study demonstrated a drop in the false positive rate by

13%. This underscores the importance of a prior clinical examination and testing only in the right circumstances.

To our knowledge this is the first clinical audit of a

single immunology laboratory from India, where disease profile, especially of infectious disease, is different

as compared to populations previously studied. Our

study has a few limitations: a tertiary care hospital setting where patients with severe disease are likely to

come, lack of samples from departments of ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, which are potential sources

of patients of AAV, and assessment of clinical details in

only the positive test samples. It is possible that we may

have missed patients of renal limited vasculitis in whom

biopsy was not performed, a possible reason why no

AAV patients without ANCA positivity were found.

Thus in conclusion testing of sera by both IIF and

specific ELISA and use of a clinical filter prior to testing

can reduce false positive rates and bring down healthcare costs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SP and AA contributed in planning the work, data

retrieval, analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

AA, VA, AL, RM were involved in reporting of ANCA.

International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2016

Audit of ANCA testing

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any disclosures.

REFERENCES

1 Falk RJ, Jennette JC (1988) Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic

autoantibodies with specificity for myeloperoxidase in

patients with systemic vasculitis and idiopathic necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis. N Engl J Med 318,

16517.

2 Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA et al. (2013) 2012 revised

international Chapel Hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 65, 111.

3 Cohen Tervaert JW, van der Woude FJ, Fauci AS et al.

(1989) Association between active Wegeners granulomatosis and anticytoplasmic antibodies. Arch Intern Med

149, 24615.

4 Arias-Loste MT, Bonilla G, Moraleja I et al. (2013) Presence

of anti-proteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

(anti- PR3 ANCA) as serologic markers in inflammatory

bowel disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 45, 10916.

5 Deniziaut G, Ballot E, Johanet C (2013) Antineutrophil

cyto- plasmic auto-antibodies (ANCA) in autoimmune

hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Res

Hepatol Gastroenterol 37, 1057.

6 Savige J, Gillis D, Benson E et al. (1999) International

consensus statement on testing and reporting of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Am J Clin Pathol

111, 50713.

7 Savige J, Dimech W, Fritzler M et al. (2003) Addendum to

the International consensus statement on testing and

reporting of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies: quality control guide- lines, comments, and recommendations

for testing in other autoimmune diseases. Am J Clin Pathol

120, 3128.

8 Hagen EC, Daha MR, Hermans J et al. (1998) Diagnostic

value of standardized assays for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in idiopathic systemic vasculitis. Kidney Int

53, 74353.

9 Harris A, Gilles D, Vadas M, Chang G (2000) ELISA is the

superior method for detecting antineutrophil cytoplasmic

antibodies in the diagnosis of systemic necrotizing vasculitis. J Clin Pathol 53, 6445.

10 Segelmark M, Westman K, Wieslander J (2000) How and

why should we detect ANCA? Clin Exp Rheumatol 18,

62935.

11 Hedger NA, Roderick P, Drey N et al. (2000) Incidence

and outcome of pauci-immune rapidly progressive

glomerulonephritis (RPGN) in Wessex, UKa ten year

retrospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15, 15939.

12 Stone JH, Talor M, Stebbing J et al. (2000) Test characteristics of immunofluorescence and ELISA tests in 856 consecutive patients with possible ANCA-associated conditions.

Arthritis Care Res 13, 42434.

International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2016

13 Suhail T, Wolf RE, Hearth-Holmes M (1999) Seven year

analysis of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)

utilization in an academic hospital. Arthritis Rheum 42,

S316.

14 Mandl LA (2002) Using antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing to diagnose vasculitis: can test- ordering

guidelines improve diagnostic accuracy? Arch Intern Med

162, 150914.

15 McLaren JS, Stimson RH, McRorie ER et al. (2001) The

diagnostic value of anti- neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

testing in a routine clinical setting. QJM 94, 61521.

16 Choi HK, Liu S, Merkel PA, Colditz G, Niles JL (1999)

Diagnostic value of ANCA testing for idiopathic systemic

vasculitis syndromes. A meta-analysis with focus on antimyeloperoxidase, p-ANCA and combined testing systems.

Arthritis Rheum 42, S175.

17 Afeltra A, Sebastiani GD, Galezzi M et al. (1996) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in synovial fluid and in

serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other

types of synovitis. J Rheumatol 23, 105.

18 Rao JK, Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Allen NB, Landsman

P, Feussner JR (1995) The role of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA) testing in the diagnosis of Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med 123, 92532.

19 Ghosh K, Pradhan V, Ghosh K (2008) Background noise

of infection for using ANCA as a diagnostic tool for vasculitis in tropical and developing countries. Parasitol Res

102, 10935.

20 Pradhan V, Badakere SS, Shankar Kumar U (2004)

Increased incidence of cytoplasmic ANCA (cANCA) and

other autoantibodies in leprosy patients from western

India. Lepr Rev 75, 506.

21 Flores-Suarez LF, Cabiedes J, Villa AR, van der Woude FJ,

Alcocer-Varela J (2003) Prevalence of antineutrophil cytoplas- mic autoantibodies in patients with tuberculosis.

Rheumatology (Oxford) 42, 2239.

22 Pradhan VD, Badakere SS, Ghosh K, Pawar AR (2004)

Spectrum of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in

patients with pulmonary tuberculosis overlaps with that

of Wegeners granulomatosis. Indian J Med Sci 58,

2838.

23 Lima I, Oliveira RC, Cabral MS et al. (2014) Anti-PR3 and

anti-MPO antibodies are not present in sera of patients

with pulmonary tuberculosis. Rheumatol Int 34, 12314.

24 Radice A, Bianchi L, Sinico R (2003) Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies: methodological aspects and clinical significance in systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev 12,

48795.

25 Arnold DF, Timms A, Lugmani R, Misbah SA (2010) Does

a gating policy for ANCA overlook patients with ANCA

associated vasculitis? An audit of 263 patients. J Clin Pathol

63, 67880.

26 Sinclair D, Saas M, Stevens JM (2004) The effect of a

symptom related gating policy on ANCA requests in routine clinical practice. J Clin Pathol 57, 1314.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Family Nursing Care PlanDocumento2 páginasFamily Nursing Care PlanJoeven Hilario83% (6)

- Doh Programs PDFDocumento68 páginasDoh Programs PDFMikaela Lozano100% (1)

- Oregano (Origanum Vulgare) and Pili (Canarium Ovatum) Sap As An Alternative Mosquito Coil RepellentDocumento47 páginasOregano (Origanum Vulgare) and Pili (Canarium Ovatum) Sap As An Alternative Mosquito Coil Repellentjenny sabas77% (13)

- Chapter 9 SpedDocumento7 páginasChapter 9 SpedAnonymous qXTFT6Ainda não há avaliações

- Salmonella Infections Clinical Immunological and Molecular Aspects Advances in Molecular and Cellular Microbiology PDFDocumento402 páginasSalmonella Infections Clinical Immunological and Molecular Aspects Advances in Molecular and Cellular Microbiology PDFFredAinda não há avaliações

- Research PaperDocumento15 páginasResearch PaperKeithryn Lee OrtizAinda não há avaliações

- Patricia DanzonDocumento4 páginasPatricia Danzonranjan tyagiAinda não há avaliações

- WEEK 8 Bacterial PathogenesisDocumento13 páginasWEEK 8 Bacterial PathogenesisotaibynaifAinda não há avaliações

- Dermatoses of PregnancyDocumento68 páginasDermatoses of PregnancypksaraoAinda não há avaliações

- National HIV, AIDS and STI Prevention and Control ProgramDocumento39 páginasNational HIV, AIDS and STI Prevention and Control ProgramR'mon Ian Castro SantosAinda não há avaliações

- 9 Example Thesis For SOP 2014-02-10Documento31 páginas9 Example Thesis For SOP 2014-02-10phileasfoggscribAinda não há avaliações

- Microbial Agents of Ob-Gyn InfectionsDocumento61 páginasMicrobial Agents of Ob-Gyn InfectionsSadam_fasterAinda não há avaliações

- EpidemiologyDocumento89 páginasEpidemiologyKrishnaveni MurugeshAinda não há avaliações

- Position PaperDocumento2 páginasPosition PaperGeojanni Pangibitan100% (1)

- Water Recreation and DiseaseDocumento260 páginasWater Recreation and Diseasetuyetnam24Ainda não há avaliações

- DISEASES Kawasaki, RHD, Is HPN)Documento9 páginasDISEASES Kawasaki, RHD, Is HPN)jenn212Ainda não há avaliações

- Bijnor Thesis Research by Pragya SrivastavaDocumento291 páginasBijnor Thesis Research by Pragya SrivastavaPragya Srivastava AgrawalAinda não há avaliações

- Reportorial RubricDocumento3 páginasReportorial RubricDerrick HartAinda não há avaliações

- LKPD Reading New ItemDocumento4 páginasLKPD Reading New ItemM. Feri afriantoAinda não há avaliações

- Chocolate AgarDocumento5 páginasChocolate AgarBramita Beta ArnandaAinda não há avaliações

- 3rd Periodic Exam-Health Care ServiceDocumento6 páginas3rd Periodic Exam-Health Care ServiceCrystal Ann Monsale Tadiamon100% (1)

- A Short History of WaterDocumento10 páginasA Short History of WatermnettorgAinda não há avaliações

- Nifedipine and Prednisone Drug StudyDocumento4 páginasNifedipine and Prednisone Drug StudyJomer GonzalesAinda não há avaliações

- Magnitude of Maternal and Child Health ProblemDocumento8 páginasMagnitude of Maternal and Child Health Problempinkydevi97% (34)

- Lecture 5 Epidemiology and BiostatisticsDocumento20 páginasLecture 5 Epidemiology and Biostatistics7ossam AbduAinda não há avaliações

- FalciparumDocumento4 páginasFalciparumDandun Dannie-DunAinda não há avaliações

- Letter To Minister of Finance April 3 2020Documento2 páginasLetter To Minister of Finance April 3 2020B.C. Government and Service Employees' UnionAinda não há avaliações

- Preventing and Managing COVID-19 Across Long-Term Care ServicesDocumento8 páginasPreventing and Managing COVID-19 Across Long-Term Care ServicesMark Anthony MadridanoAinda não há avaliações

- HIV Policy AssignmentDocumento4 páginasHIV Policy AssignmentEdmore MarimaAinda não há avaliações

- Isolation PrecautionsDocumento13 páginasIsolation Precautionsmalyn1218Ainda não há avaliações