Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Doctrinal and Non-Doctrinal Legal Research PDF

Enviado por

Kunal SinghTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Doctrinal and Non-Doctrinal Legal Research PDF

Enviado por

Kunal SinghDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL

LEGAL RESEARCH

s.N. Jain"

I. Doctrinal research and social values

LA W IS a normatiy~ien&J;. that is., a science which lays down norms

situation or situations

and standards for human behaviour in ~.

enforceable throu'&!! tfie-salIs:.tiWl~Lthe- state. What distinguishesIaw

From'othersocial sciences (and law is a social science on account of the

simple fact that it regulates human conduct and relationship) is its

. normative character. This

fact along with

the fact that stability and

I

.-----'certainty of law are desirable goals and social values to be pursued, make

dOctriiuil research to be of primary concern to a legal researcher.

DOe-irana" resear~h,-of c;~rse: involves analysis of~~w...l..arrl!!!ging,

ordenDs and syitem3h.sj.ng Je~alpropositions. and study of legal

i~ions. wt iLdoes .more=-it!,~at~s law and its JnliQI !9.01 (but not

t~!.EI!!y_!ool) t~~ is .!.llr9ygbJ~ea.soniJl&. or rational deduction.

!l.venduring The..period when..analytical.p.QsitiYJ-s!l1_h.eld~ s.~~L!!!g the

~ant legal.pl1ilosqphy was that judges did not create law but merely

declared it, the t!..utj1 wasthat much judicial creativi~ was gOln'g~on~ The

development of common .law by th~_ C0l1'lJll.OIL h;tW j)1des...i.S .,~ar

example of law-making by the judges. has been commented upon the

...

traditional view:

specHieo

It

While the traditional theory may appear more plausible in a

period characterized by relatively stable conditions, as opposed

to one in which great changes and developments are clearly

evident, it is still difficylt to see how one could literally beli.$ve

the law to be a coherent and complete system, and the judicial

process to be only a togical ap'p~~tJQ~ o(ex'istin!L~tit~ofj~w.

Pro"Cessor Cooperrider has made the plausible suggestion that the

traditional .theory was not intended as an accurate descriptive

This paper is a supplement to the author's earlier paper. "Legal Research and

Methodology", 14 JIL/487 (1972).

Reprinted from 17 Journal of the Indian Law Institute 516-536 ( 1975) .

L.L.M., S.J.D. (Northwestern), Director, Indian Law Institute, New Deihl.

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCH

69

account of the judicial process : ... .1 am also inclined to doubt

that it is sound to think of it as a conscious attempt at scientific

description. It did, however, represent a view which at one time

was generally held as to the attitude which the judge should

bring to his task: that it should be his objective to deal with the

case before him in that way which was indicated by an

interpretation of existing authorities, rather than in that way

which seemed to him on the facts to be the fairest or most

desirable from a social point ofview. It called for the subordination

of his judgment to that of the collectivity of his predecessors,

for a primary reliance on a reasoned extrapolation of accumulated

experience.' [The Rule of Law and the Judicial Process, 50

Mich. L. Rev. 505-06 (1961)]. According to this interpretation,

the traditional theory represents more a practical regulative ideal

of how the judicial process ought to be conceived by the judiciary

than a theoretical analysis of its actual structure and functioning. I

That even in that case-law method of research much creativity goes

on isS~~~dozo1illilS~o~~eNature ofthe Judicial Process.

Rls thesis is that law or legal propositlonsarenot tinaI or absolute-but

are in the state of becoming. He quotes Munroe Smith :

T~s and principles of case law have neve.r ~~~!! t~e~t~fI ~s

fi,!!,al truffis,1ffifirwof"king hypotheses,"continually rete~!ed i!1

those great labOraiones of the liW,tJie

courts of justice.

Every

new-case fs'ill;~experimel1t; an<Hf the accepted rule which seems

applicable yields a result which is felt to be unjust. the rule is

reconsidered. It may not be modified at once, for the attempt to

do absolute justice in every single case would make the

development and maintenance of general rules impossible; but if

a rule continues to work injustice, it will eventually be

reformulated. The principles themselves are continually retested;

for if the rules derived from a principle do not work well, the

principle itself must ultimately be re-exarnined.I

He himself says:

Hardly a rule of today but may be matched by its opposite of

yesterday....These changes or most of them have been wrought

by judges. The men who wrought them used the same tools as

the judges of today. The changes, as they were made in this case

I. Boonin, "Concerning the Relation of Logic to Law", 17 J. Legal Ed, 155 at 158159 (1964-65). Emphasis as in the original.

2. Quoted in The Nature of the Judicial Process 23 (1921).

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

70

or that. may not have seemed momentous in the making. The

result. however, when the process was prolonged throughout

the years. has been 110t merely to supplement or modify; it has

been to revolutionalize and transform.'

The two oytstapdipi examp,l.e.sJ>.f.the..c!:c:~~~tx <?( doctrinal resea~.h

.ire the law petorts and adminis!rative law. About the latter, for insta~e.

it has been remarked:

- - - --' .. _~--_._-~

The creation of.a body of law where none had ~itherto existed

"is a social achievement It is an ..wiliievement not to be "MerS~ti,ID,~~.Ili~~-asJl.r.cminderthaLat parti~Jar p~r!~~..s

in the history of law the creative working out of legal doctrine

1$ both necessary andcri-iTcal ilOd]ustitiablya paramount concern

of legal research. 4

.. ,.-......- . ' - - .-~.-

------

It may not be out of place to mention that in India it was the

pioneering work of A.T. Markose on Judical Control of Administrative

Action and the seminars organised and the work done by the Indian Law

Institute in the area of administrative law which had created an awareness

of the importance of the subject for the legal system.

With the emergence Qf t.he..sPEologica~cho<&.the cre~tive r~l~ _oj

lawyers apdju.d~ha1~.lO~~j~~.d _e':'p'li.~t!y.:._I~e writings

ofthe soci()logicaljl1.ris~s ~.Qm~Jiied_ with..!I!e phange in,p.o1iti~.al.p'h!los~p~y

~11!~J}i..JQi~3..e,z jaj!e to th~ welJare .1tM~ 51r_~~.re rather the result 01 t~is

metamorphosis. One can see the seeds of the conception of Jaw as a

catalytic agentto advance human welfare in the following famous

remarks of Justice Holmes:

T.!t~Jife ~f the law-hil~t beenhi~ic : it has been experienc;..

The J~JtP-~essities of the time.....t e prevalent moral ~nd political

theories . intuitions ..Q(p'!tilicpolicy. avowed or unconscious...

even the prejudices which jl.!dies sh.~e-Wii11 tneti fellOwmen.

have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism In-determining

die rules by which men should be governed.!

-. --.--

The writings ~f Dean Roscoe_.~o,!1.!!~.!. however. depict more cl~~rl,y

a.nd lOrcefWly ilie.Ja$k.9L~\Y ~_b_eth.~ adjus~~tmt of h~!"anreJati~~~hip

in society to the best possible advantage. Thus. he says :

3. Jd. at 26-28.

4. N.D. Grundstein, "Administrative Law and the Behavioral and Management

Sciences", 17 J. Legal Ed. 121 at 122 (1964-65).

5. Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Common Law I (1881).

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCH

71

For the purpose of understanding the law of today I am content

with a picture of satisfying as much of the whole body of human

wants as we may with the least sacrifice. I am content to think

of law as a social institution to satisfy social wants-the claims

and deniaiids and expectations involved in the existence of

civilized society-by giving effect to as much as we may with

the least sacrifice, so far as such wants may be satisfied or such

claims given effect by an ordering of human conduct through

politically organised society. For present purposes I am content

to see in legal history the record of a continually wider recognizing

and satisfying of human wants or claims or desires through

social control; a more embracing and more effective securing of

social interests; a continually more complete and effective

elimination of waste and precluding of friction in human enjoyment

ofthe goods of existence-in short, a continually more efficacious

social engineering.6

-c

At another place he says

As the saying is, we all want the earth. We all have a multiplicity

of desires and demands which we seek to satisfy. There are very

many of us but there is only one earth. The desires of each

continually conflict with or overlap those of his neighbours. So

there is, as one might say, a great task of social engineering.

There is a task of making the goods of existence, the means of

satisfying the demands and desires of men living together in a

politically organised society, if they cannot satisfy all the claims

that men make upon them, at least go round as far as possible.

This is what we mean when we say that the end of law is

justice ....We mean such an adjustment of relations and ordering

of conduct as will make the goods of existence, the means of

satisfying human claims to have things and do things, go round

as far as possible with the least friction and waste.

The task of law as that of social engineering has come to be

accepted as a dogma by the civilized societies all over the world including

India. The chapters on fundamental rights and directive principles of

state policy of the Constitution of India embody this philosophy. The

concern of law as an instrument of economic and social justice has

grown to such an extent that there is hardly any human conduct which

has been left untouched by law. The result is that there has been an

explosion of laws and the law has become all pervading. We have come

6 . Roscoe Pound, Introduction to the Philosophy oJLaw 4 1 ( 1 963).

7. Roscoe Pound, Social Control Through Law 64-65 ( 1 968).

72

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

to live in an age of laws. The legislative mill has been constantly pouring

out laws. This is not the only factory for producing statutory laws. The

executive made law (delegated legislation) has become much more

important both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Jhe present emphasis of law on achieving the social welfare of the

people along with the fact of great economic and technological advancements have placed great burdens on law ~.e....2!!!1S_Qf.la~. Because

of the necessity to enact Iaw~-Q!l, complex and ~erse...s~~ts it has

become inevliablefor 'the 'iesislature_!~_l~~v~gaps J~. jhe s.tatl,lt.es,-'aridg,e~etlf~-gt~'aiscretion

!llesoUJ:t$tp evolve doctrines, principles.

standards and norms themselves in the process of _a"pp'licati~r:t of the law

from case "to case. Further, the complexity of laws has given scope for

ambiguities Tn llie~~uiorylanguageorscheme. Then a word used ina

statute, which may appear to be fairly clear at the time of enactment of

the statute, may acquire vagueness when the occasion of its application to

a case by the court arises. Similarly, the plain statutory language maYloSe

Its plainness at the time of actual controversy because oTihe human

limitation to foresee all the difficulties and' nuances of the problem. A few

examplesmay be taken from "the Indian statute book to illustrate some of

these points.

"

An example, par excellence, of the legislature conferring discretion

on the courts is that of article 19 of the Constitution which permits the

state to impose reasonable restrictions on the various rights guaranteed

to the citizens by that article. There is no definite test to judge the

reasonableness of a restriction, and the Supreme Court itself has stated:

"'ii

In evaluating such elusive factors and forming their own

~~ri~eption of what is reasonable in all the circumstances oCa

given case, it is inevi~"aQJ.c; tlmttb..!Q@J.1mi!oso.l?hy..a nd the scale

~~~s of the}u~g~s p~rticipatiJ.1g in ~h~ ~e~ision sg'<>J!l<LPlay

an Important part, and the limit to their interference with legislative

iUdgmerit in such cases can only be dictated by their sense of

responsibility and self restraint and the sobering reflection ,that

'the Constitution is meant not only for people of their way of

thinking but for all. that the majority of the elected representatives

of the people have, in authorising the imposition of the restrictions.

considered them to be reasonable.!

In considering reasonableness of a restriction the task before the

courts is to judge the objective of public interest to be served by the

restriction against fairness to the individual.

The Indian statute book is replete with provisions where the legislature

has given discretion to the courts to develop the law from case to case.

8. State of Madras v . VG. Row, AIR 1952 SC 196 at 200,

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCH

73

A few examples may be given here. Use of such phrases as "just and

equitable't.? "public order", 10 "inexpedient'"?" "reasonable opportunity of

being heard" 1I "reasons to believe",12 "undue and unreasonable preference't.!' "acting under colour of office", 14 "reasonable sum".'! "rash

or negligent act",16 "reasonable apprehension";'? "reasonable cause'"!

"oppression and mismanagement't.!? are only a few of the illustrations

amongst the host of statutory provisions. Also even such words or

phrases as "sale" for sales tax purposes, "interstate sale", "annual letting

value", "fraud" for declaring a marriage as "nullity", "industry", "industrial

dispute", "business expenses", "best judgment assessment", "obscenity"

and innumerable such other phrases have presented a wide scope for the

exercise of judicial discretion. It may not be wrong to say that the

amorphous mass of the present day statutory provisions take concrete

shape and form in the great laboratories of the law courts, and this

applies even to those statutory provisions which appeared to be precise,

articulate and clear at the time of their enactment. The fact is that "all

rules have a penumbra of uncertainty where the judge must choose

between alternatives"."?"

Apart from this, while interpreting certain clauses, the judiciary itself

has evolved certain standards which are vague and flexible. Three good

examples in this respect from the area ofconstitutional law are "reasonable

classification" under article 14, "direct and indirect restriction" under

part XIII of the Constitution, and "the basic feature theory" for purposes

of amending the Constitution. A few branches of the law have been more

or less entirely developed by the judiciary. The two modem illustrations

are labour law and administrative law. Taking a leaf from administrative

law, such judicially created phrases as "excessive delegation" (to test the

validity of the delegated legislation) or "ultra vires" (to test the validity

of administrative action) or "no legal evidence rule", or "error of law

apparent on the face of the record" leave an area of wide discretion for

9. Section 433, the Companies Act, 1956.

10. Section 3, the Maintenance of Internal Security Act, 1971.

IDa. Section 7-A, the U.P. (Temporary) Control of Rent and Eviction Act, 1947.

I I. This phrase is used in innumerable statutes, see particularly, article 311 of the

Constitution of India.

12. Section 147, the. Income Tax Act, 1961.

13. Section 28, the Indian Railways Act.

14. Section 99, the Indian Penal Code.

15. Section 74, the Indian Contract Act.

16. Section 304-A, the Indian Penal Code.

17. Section 10, the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955.

18. Ibid.

19. Sections 397 and 398, the Companies Act, 1956.

19a. Hart, The Concept of Law 12 (1961).

74

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

the courts to operate. In doing so they have to draw nice lines between,

and balance, the interests of the individual to protect him from arbitrary

government and administrative effectiveness and public interest. The

application of these phrases in a given situation calls for a great deal of

value judgment and "painful adjustment of conflicting values".20

A brief survey of the statutory provisions leads to one inescapable

conclusion. In modem times, case-law based research is concerned to

a very large extent with considerations of social value, social policy and

the social utility of law and any legal proposition. It is naive to think that

the task of a doctrinal researcher is merely mechanical-a simple

application of a clear precedent or statutory provision to the problem in

hand, or dry deductive logic to solve a new problem. He may look for

his value premises in the statutory provisions, cases, history in his own

rationality and meaning of justice. He knows that there are several

alternative solutions to a problem (even this applies to a lawyer who is

arguing a case before a court or an administrative authority) and that he

has to adopt one which achieves the best interests of the society. The

judges always unconsciously or without admitting think of the social

utility of their decisions, but cases are also not infrequent when the

Indian Supreme Court has consciously and deliberately incorporated

social values in the process of its reasoning. To take a few examples

here, in Bengal Immunity Co. v. State of Bihar. 21 the court, while

overruling State of Bombay v. United Motors,22 stated:

All big traders will have to get themselves registered in each

State, study the Sales Tax Acts of each State. conform to the

requirements of all State laws which are by no means uniform

and, finally, may be simultaneously called upon to produce their

books of account in support of their returns before the officers

of each State. Anybody who has any practical experience of the

working of the sales tax laws of the different States knows how

long books are detained by officers of each State during

assessment proceedings.... The harassment to traders is quite

obvious and needs no exaggeration.P

In Jyoti Pershad v. Union Territory of Delhi,24 the Supreme Co uri

observed:

The criteria for determining the degree of restriction on the right

to hold property which would be considered reasonable, are by

20. Friedmann. Law in a Changing Society 384 (1972).

21. AIR 1955 SC661.

22. AIR 1953 SC 252.

23. Supra note 21 at 687.

24. AIR 1961 SC 1602.

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAI_ LEGAL RESEAR(H

75

no means fixed or static, but must obviously vary from age to

age and be related to the adjustments necessary to solve the

problems which communities face from time to time" "I flaw

failed to take account of unusual situations of pressing urgency

arising in the country, and of the social urges generated by the

patterns of thought-evolution and of social consciousness which

we witness in the second half of this century, it would have to

be written down as having failed in the very purpose of its

existence... .In the construction of such laws and particularly in

judging of their validity the Courts have necessarily to approach

it from the point of view of furthering the social interest which

it is the purpose of the legislation to promote, for the Courts ,are

not, in these matters, functioning as it were in vacuo, but as

parts of a society which is trying, by enacted law, to solve its

problems and achieve social concord and peaceful adjustment

and thus furthering the moral and material progress of the

community as a whole. 25

In the famous Go/ak Nath v, State of PU11;ab,26 Subba Rao, C.J"

said:

But, having regard to the past history of our country, it could not

implicitly believe the representatives of the people, for uncontrolled

and unrestricted power might lead to an authoritarian State, It,

therefore, preserves the natural rights against the State encroachment and constitutes the higher judiciary of the State as the

sentinel of the said rights and the balancing wheel between the

rights, subject to social control. 27

The court's concern with social justice is depicted forcefully in the

following observations of Bhagwati, J., in Kanwarlal v, Amurnath :21\

This produces anti-democratic effects in that a political party or

individual backed by the affluent and wealthy would be able to

secure a greater representation than a political party or individual

who is without any links with affluence or wealth. This would

result in serious discrimination between one political party or

individual and another on the basis of money power, and that in

its turn would mean that "some voters are denied an 'equal'

voice and some candidates are denied an 'equal chance?" .... The

democratic process can function efficiently and effectively for

25.

26.

27.

28.

Id. at 1613.

AIR 1967 SC 1643.

Id. at 1655.

AIR 1975 SC 308.

76

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGr

the benefit of the common good and reach out the benefits of

self government to the common man only if it brings about a

participatory democracy in which every man, however lowly or

humble he may be, should be able to participate on a footing of

equality with others. Individuals with grievances, men and women

with ideas and vision are the sources of any society's power to

improve itself. Government by consent means that such individuals

must eventually be able to find groups that will work with them

and must be able to make their voices heard in these groups and

no group should be insulated from competition and criticism. It

is only by the maintenance of such conditions that democracy

can thrive and prosper and this can be ensured only by limiting

the expenditure which may be incurred in connection with

elections, so that, as far as possible no one single political party

or individual can have unfair advantage over the other by reason

of its larger resources and the resources available for being

utilised in the electoral process are within reasonable bounds and

not unduly disparate and the electoral contest becomes evenly

matched. Then alone the small man will come into his own and

will be able to secure proper representation in our legislative

bodies.

The other objective of limiting expenditure is to eliminate. as far

as possible, the influence of big money in the electoral process.

If there were no limit on expenditure, political parties would go

all out for collecting contributions and obviously the largest

contributions would be from the rich and affluent who constitute

but a fraction of the electorate. The pernicious influences of big

money would then play a decisive role in controlling the

democratic process in the country. This would inevitably lead to

the worst form of political corruption and that in its wake is

bound to produce other vices at all levels.I?

Finally, while considering the judges' role in determining questions

of "public policy", Mathew, J. said in Murlidhar v. State 4 u.P. :2l){/

There is no alternative under our system but to vest this power

with judges. The difficulty of discovering what public policy is at

any given moment certainly does not absolve the judges from the

duty of doing so. In conducting an enquiry...judges are not

hidebound by precedent. The judges must look beyond the narrow

field of past precedents, though this still leaves open the question,

29. /d. at 314-15.

290. AIR 1974 SC 1924.

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL I.GAL RSEARCII

77

in which direction he (sic) must cast his (sic) gaze. The judges are

to base their decision on the opinions of men of the world, as

distinguished from opinions based on legal learning. In other

words, the judges will have to look beyond the jurisprudence and

that in so doing, they must consult not their own personal standards

or predilections but those of the dominant opinion at a given

moment, or what has been termed customary morality. The

judges must consider the social consequences of the rule

propounded, especially in the light of the factual evidence available

as to its probable results. 29b

~hu~tQ~.object~ve and philosophy of doctrinal re,~Earcher has to be

the same as that of sociological jurisprudence; that is, social engineering

tlirough law. In this sense he is a sociological jurist, thoug!!.J! is_~~~at

his liberty of op-eratlon 'is' -res'fiicled' to some extent by the statutory

language, existing doctrines and also the consciousness thaLL.sound

f~~_s!,st~m_shoufd move towards certainty and stability of law which

are social values to be desired. But, as seen above, the law in modern

ti'ilieSleaveSa-iarge'scope,a tinge leeway, and the-leeway'may'be more

i'!.~tEe me'S aniness inothers but it is there, for moulding anQ aE~jHing

it to the society and to social change. This has been additionally fac!liJilted

iii"Tndiilby the Supreme Courtexpressly agreeing as a principle...t.o.r.eview

Its own decisions.' and a number of instances can be cited where: the

c~~,~ _d~~e~ .. !~~ ~process began with the court .Qv~I'J!lILqg jhe

United Motors cas~o in the Bengal Immunity case" and its high watermark

was reached when in the famous Golak Nath case,32 it overruled its

consistent holding in the two earlier cases-Shankari Prasad 33 and

Sajjan Singh. 34 A few other instances of such overruling are: Director

of Rationing v. Corporation of Calcutta'? by Superintendent and

Remembrancer of Legal Affairs v. Corporation of Calcutta/" Indian

Airlines Corporotion v. Sukhdeo Rai 37 by Sukhdev Singh v. Blwgatram,J8

Sardarilal v. Union of India'? by Samsher Singh v. State of Punjab.t"

29b. /d. at 1930.

30.

3 I.

32.

33.

34.

State of Bombay v. United Motors. supra note 22.

Bengal Immunity Co. v. State of Bihar, supra note 21,

Golak Nath v. State of Punjab, supra note 26.

Shankari Prasad v. Union of India, AIR 1951 SC 458.

Sajjan Singh v. State of Rajasthan, AIR 1965 SC 845.

35.

36.

37,

38.

39.

40.

AIR

AIR

AIR

AIR

AIR

AIR

1960

1967

1971

1975

1971

1974

SC

SC

SC

SC

SC

SC

1355.

997.

1828.

1331.

1547.

2192.

78

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METIIODOLOGr

Any number of cases can be cited when the court without expressly

overrulmg Its earlier decIsions a~artea from tnemor weaKened their

..~,_.. ,--~.~- ---- '-'-'-~--'-'''' .. _.

illthoflty' or modified the principles laid down (sometimes in t ie garo of

aevelopmg them iuriherrSuch cases are demonstrative of tht: fact that

the language of the statute1S-riot petr1f1ed..for a[1 fhhes- to come alief i IS

ineaning and impact c~a.n&eIn. th~ .c,!ts:lytic ha~ds OC~!;<O:l~e~~

The.jjIJb w is WJll,lnwjndfl.lUU.Jbe .fact that sometimes a doctrinal

rese;cher mi)' Jack ~. uliJitC\{!.an, ~m2[Qa.h....alld,'hijQiecoiiC'ern maY}~

te~t__th~.J()i.i~~, co~si~!encL~l!5! t.t~hnif&.s()!.11!4J}~s.s ,g1...~_~~~.r a

legal proposition by analysing it with reference to the precedential

symmetry and' on the anvil of strjcJ.l!t~JaLQ!~a,ningllD'..Ke_ep!ng:gramu1ar

and d!ct~Qnary in (me hand and the statutory lang,uage in~h.e.-2!h.c:.r).

Technical soundness of the law is not unimportant "bliilt shol.!lq .1].ot

o~rafe m v~~_uum-andought"to be balanced, wherever there is scope.

against social policy and motes' of-the'-society:,

,

"".-----.--

rc:

II. Sociology of law

From where does a doctrinal researcher get his social policy. social

facts and social values? The answer is, his own experience, observation.

reflection and study of what others have done before him in a similar or

same kind of situation. However, it will certainty add value to his

research if he gets an opportunity to test his ideas by sociological data.

And this is what the author understands by the sociology of law. In other

words, the sociology of law tries to investigate through empirical data

how law and legal institutions affect human attitudes and what impact on

society they create. It seeks answers to such questions as-are law and

legal institutions serving the needs of the society? Are they suited to the

society in which they are operating? What factors influence the decisions

of adjudicators (courts or administrative agencies)? Are the laws properly

administered and enforced (or do they exist only in text-book)? -The

sociology of law also concerns itself with the identification and creating

an awareness of the new problems which need to be tackled through

law.

Just as a matter of semantics. the author will use the term "sociology

of law" where the major tools of a legal researcher are empirical and

sociological data. This is to be distinguished from sociological

jurisprudence and, as stated earlier, a doctrinal researcher has to be but

a sociological jurist because of the wide discretion available to him in

modern times to make his value choices.

Though sociology of law may have great potentialities. yet a few

caveats must be entered here. Firstly, sociological research is extremely

time consuming and costly. It has been stated: "Socio-legal research is

more expensive, it calls for additional training; and it entails great

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCII

7')

commitments of time and energy to produce meaningful results, either

for policy-makers or theory-builders.?"' The decisions in human affairs.

however. cannot await the findings of such studies and must constantly

be made. and herein comes the value and utility of doctrinal research.

Thus, "Doctrinal legal research ... has had the practical purpose of

providing lawyers, judges and others with the tools needed to reach

decisions on an immense variety of problems. usually with very limited

time at disposaJ."42 In this context K.C. Davis also observes:

[I]t may be a hundred or several hundred years before we get

truly scientific answers to some of the questions I am trying to

explore, and we need to make some judgments in the meantime.

Some of the most useful thinking can be unscientific,

impressionistic, intuitive based on inadequate observation or

insufficient data or wild guesses or imagination. Scientific findings

are obviously the long term objective, but a good many judgments

which fall far short of scientific findings are valuable. respectable

and urgently needed.v'

Secondly, law-sociology research needs a strong base of doctrinal

research. Upendra Baxi rightly points out that "law-society research

cannot thrive on a weak infra-structure base of doctrinal type analyses

of the authoritative legal materials.T'" The reason is simple. The primary

objectives of the sociology of law are to reveal, by empirical research.

how law and legal institutions operate in society, to improve the contents

of law, both in substantive and procedural aspects, to improve the

structure and functioning of legal institutions whether engaged in law

administration, law enforcement, or settlement of disputes (adjudicatory

process), and these objectives cannot be achieved unless the researcher

has in-depth knowledge of the legal doctrines, case law and legal

institutions. Further, such a knowledge is essential for identifying issues,

delimiting areas, keeping the goals in view, and determining the hypotheses

on which to proceed. In the absence of these, the sociological research

will be like a boat without a rudder and a compass, left in the open sea.

The whole exercise may be fruitless. The authors of the monograph on

Law and Development were perhaps conscious of this when they

said:

41. International Legal Center, Law and Development, 10, (New York. 1(74).

42. Vilhelm Aubert (Ed.), Sociololy of Law 9 (1969).

43. K.C. Davis, "Behavioral Science and Administrative Law", 17.J. l.egu! F.cI 137

at 151-52 (1964-65).

44. Upendra Bax i, Sacio-Legal Research ill India : A Programschrijt 7 (ICSSR.

1975).

80

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

[W]e should make clear that we do not denigrate doctrinal

research, which has a proud tradition of outstanding scholarship.

Nor do we seek to minimise the importance of doctrinal research

to the establishment and functioning of a legal system and thus

to society. We are also conscious that in many of the countries

we were concerned with, there is an absence of basic doctrinal

research and indeed not infrequently the tools and raw materials

of such research. While the situation varies between countries,

we recognise that in some countries doctrinal research could

claim a high priority in allocations of the resources available for

legal research.P

In India where we still lack the infra-structure of doctrinal research,

such a research will naturally have to claim high priority.

Thirdly, sociological research may help in building general theories,

but it seems inadequate where the problems are to be solved and the law

is to be developed from case to case. For instance, as a matter of general

theory it is axiomatic that governmental powers need to be checked as

"power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely", but too much

check may result in governmental ineffectiveness. This necessitates that

when a case comes before a court in which abuse of power by the

executive is alleged, pragmatic considerations ought to control the

decision-making. Since the law to control governmental action develops

from case to case, it will not do to theorise that either there should be

no control over governmental action or there should be adequate control.

That is why it has been said about the ultra vires doctrine, which is the

basis of judicial review in case of writs :

The ultra vires doctrine provides a half way basis of judicial

review between review in appeal and no review at all.. ..The half

way review, the extent of which is not always clear, creates

uncertainty about judicial intervention in administrative action.

Sometimes, the courts may feel like intervening because they

feel strongly about the injustice of the case before them ;

sometimes they are not sure of injustice and wish to give due

deference to the expertise of the administration and uphold the

decision.t"

It is beyond the comprehension of the author how we can improve

the contents of the ultra vires doctrine by sociological research. To

illustrate the point by another example, take the case of the concept of

"sale" for purposes of sales tax. The tax is imposed only on sale and not

45. Supra note 41 at 19.

46. M.P. Jain and S.N. Jain, Principles ofAdministrative Law 363 (\973).

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCH

81

on a contract for labour or service. Now every sale of a commodity does

involve some labour. Still there may be clear cases of sale and clear

cases of labour contract (or works contract) but there may be innumerable

penumbral situations where it will be difficult to say on which side a

particular transaction falls.

Fourthly, the function of law in society is not only to follow or adapt

itself to public opinion (assuming that it is possible to know correct

public opinion) but also to give a lead and mould public opinion. When

the law should follow one course or the other may not always be

answered on the basis of sociological data but on the basis of one 's

maturity of judgment, intuition, and experience, though sociological

research may be of some informational value to the decision-maker.

Fifthly, on account of complicated settings (and this particularly

applies to economic data) and variable factors, we may again be thrown

back to our own pre-conceived ideas, prejudices and feelings in furnishing

solutions to certain problems. For instance, there has been the perennial

problem of governmental control of business or non-governmental control,

private enterprise or public enterprise (or efficiency or inefficiency of

the one or the other), and individual liberty or governmental powers. We

may not be able to answer these questions basic to any society through

scientific study.47 Even if one were to attempt such a study, it would

require such huge resources (owing to the vastness of the subjects of

inquiry) that one may not be able to have them at one's command.

Coming to a lower plane, under part XIII of the Constitution, states

cannot discriminate against interstate commerce, but at times it is not

easy to determine whether there has been discrimination or not and an

empirical study may not easily furnish the answer. This is clear from the

following extract from an article by the author :

In determining the validity of a law against a challenge on

account of discrimination against interstate commerce, multiple

taxation of such commerce, or undue burdens on it, the judiciary

has an important though a difficult role to play. Should the Court

go merely by patent or formal discrimination? Should it cut

deeper and go behind the avowed purpose of the law and attempt

to find out its actual effects? Should it examine the law in

question in the context of the entire economy? For example,

state A imposes a fifteen per cent tax on cost of alcoholic liquor

47. Kelsen says: "The issue between liberalism and socialism, for instance, is, in

great part, not really an issue over the aim of society. but rather one as to the correct

way of achieving a goal as to which men are by and large in agreement; and this issue

cannot be scientifically determined, at least not today." General Theory ofLaw and

Stale 7 (196\).

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

82

manufactured in that state. Now state B, which IS importing

liquor from state A, imposes a tax of twenty per cent on liquor

manufactured within it. How much tax should state B impose on

imported liquor? One view could be that it should impose a tax

of twenty per cent (i.e. the same percentage of tax which it is

imposing on intrastate liquor). Another view which could be

taken is that it should impose a tax of only five per cent as a

higher tax would put a burden on the imported liquor than the

intrastate liquor and would be discriminatory against the former.

There are several limitations in the latter approach. First, since

the intrastate tax on liquor is likely to differ from state to state,

the importing state will be required to impose different taxes on

imported liquor depending on the state from which it is coming.

It is doubtful whether such a tax would be possible to administer.

Second, if the tax involved is other than excise, say, sales tax,

it may be practically difficult for the importing state to know the

account of tax which an imported commodity has actually borne

in the exporting state. The structure of sales tax differs from

state to state. In some states the system is multiple point, in

some two point, in some single point on the first sale and in some

single point on the last sale. The incidence of local sales tax on

a commodity exported to another state will depend on the system

of sales tax in that state and the number of local sales. If equality

is to be achieved in the sense suggested above, then it would not

only mean the different rates on the sale of the same imported

commodity within a state depending upon the state from which

it is imported but also the rates would have to vary on a

commodity from the same state depending upon the number of

local sales in that state-a practical impossibility. Third, if real

equality is to be attained in the example relating to liquor, why

stop only at the excise duty. Why not consider all other taxes like

the propety tax and the taxes on the raw materials going into the

manufacture of liquor which will have an impact on the cost of

production of the liquor. Under the equality formula suggested

above, these should also be taken into account by the importing

state. 4 8

In spite of the readiness of the United States Supreme Court to be

receptive to economic and social data, the following quotation again is

indicative of the difficulties in this regard:

48. S.N. Jain, "Freedom of Trade and Commerce and Restraints on the State Power

to Tax Sale in the Course of Interstate Trade and Commerce". 10 JIL/547 at 563-64

( 1968).

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCH

83

In the United States, in the non-tax area the Supreme Court

usually goes deeper into various factors in order to determine

whether the law was placing an "undue" burden on interstate

commerce which "frequently entails weighing evidence, drawing

nice lines, and making close and difficult decision on important

policy questions." However, inthe tax area, probably because of

greater difficulty in evaluating complicated economic factors

involved, this has not been the general approach.... 49

Sixthly, though law-sociology research is of recent origin, yet it is

common knowledge that even in the United States, where this kind of

work has been done mostly, such researches have yet to show their

potentiality in terms of translating the findings into legal propositions and

norms. Amongst others, one reason may have been the failure to select

subjects with such potentialities. Any information has some value, but

when huge resources are to be staked in collecting sociological data it

may be better to use them on carefully planned subjects where the

research may lead to ultimate improvement of the contents of the law.

Thus, with regard to decision-making research, Davis observes :

Research on decision-making excites many people, including

Professor Grundstein, and the quantity of such research is

voluminous-even staggering. A single bibliography on decisionmaking research fills a sizable volume. so

He further says :

The down-to-earth Behavioral Research Council concludes as to

decision-making research: "The major result in the field, to date,

has been the development of a variety of theories, the testing of

which has only begun .... Little can be said about the usefulness

of the field until the testing (and in some instances the stating of

the theories in testable form) has been accomplished.t''"

Upendra Baxi, in an otherwise excellent paper, also seems to commit

the error of suggesting some of the socio-legal research topics without

stating the objectives or hypotheses from the point of their possible uses

to the legal community and law reformers, or how the researches in

those subjects may improve the normative content of the legal system or

the structure of the legal institutions. This is a major weakness of his

paper, though, of course, the collection of information on the lines

49. Id. at 565-66.

50. Davis. supra note 43 at 142.

51. Ibid.

84

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

suggested by him may be valuable for its own sake. Taking at random

three projects suggested by Baxi, comments may be made on them. He

says:

We do not have organised information on turnover, in number

and type, of legislative enactments in different states; of timelags between initiation of bills, their passage through the House,

the intervening work of joint select committees, and the timelags between passage and the gubernatorial or the Presidential

assent to the bills. Much less do we have any information on the

quantity of amending and repealing legislation, or of the private

member's bills. 52

It is not understood where Baxi wishes to lead a legal researcher or

a law reformer from the kind of information that he would like to be

collected, that is, what are the goals of such a research ? It may also be

said that with regard to the turnover of legislation it would not be

difficult to find out the same from the annual reports of the Ministries

of Law of the states, the state gazettes, and various other private

publications. Similarly, with regard to private member's bills, the facts

are common knowledge, though we may not have complete and accurate

information (and it seems to be a futile task to obtain this kind of

"accurate" information). With regard to the question of time taken and

the intervening works of the joint select committees, it is not clear as to

what he wants. Does he want quick passage of Bills, excluding the joint

select committees from consideration of Bills or does he want that there

should be greater democratisation in the sense of greater public

participation of the affected interests through the joint select committees'!

Here, perhaps, fruitful results may come out if one were to examine Bills

from the latter aspect and concentrate on why in some cases Bills were

referred to the joint select committees but not in others, since consultation

of affected interests in enacting a statute is a social goal to be achieved.

Further, Baxi points out: "Nor do we have (although useful beginnings

have been made in this direction by political scientists) much data on the

social profiles of national and state legislators".53 Here again one is left

without any idea as to how this kind of information will be of qualitative

value to law researchers or law makers or how it will help in improving

the character and composition of the legislature. Does he want some

kind of educational or professional test to be laid down for the legislators?

With the emergence of the party system and the situation where party

discipline counts more than "intelligence", and the reality of the executive

52. Baxi, supra note 44 at 25.

53. Id. at 26.

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCH

85

controlling the legislature, it is again not understood what useful purpose

will be served by collecting such a kind of information. To some extent

the information on the lines desired by Baxi is available in the various

"Who's Who",54 Further he says:

Disregarding fine distinctions between administrative 'tribunals'

and other administrative adjudicatory bodies, it would be

scientifically rewarding and socially relevant to examine typology

of litigants before a few selected tribunals/bodies.55

One fails to understand how the study of typology of litigants will

lead one to understand the role of the tribunals in the social context, and

in any case it is well known what types of litigants use these tribunals

(easy recourse is one of the virtues of these bodies). The objectives of

establishing these bodies are accessibility, cheapness, expertise, expedition

and lack of formality. It would be much more rewarding and useful to

study these bodies with a view to finding out as to how far these social

objectives have been achieved in practice (it may be pertinent to point

out that some work on these lines is being done by the Indian Law

Institute);

Perhaps Baxi wants to be modest in his research programme by

suggesting that at the initial stages we should try to gather facts about

the formal legal system, the knowledge of which we seem to lack

woefully. To substantiate him, the author would like to mention an

anecdote. A few years back he was talking to the chairman of a tribunal

which has been in existence for a number of years. He was a man of law.

He told the author that he learnt for the first time that there was such a

tribunal when he was offered its chairmanship by the government. The

suggestion made by Baxi opens up infinite possibilities for research work

and any area or subject can be taken up for fact collection depending

upon the researcher's own equipment, specialisation and value judgment

in terms of priorities. The author's own priorities will be the study of

administrative process and adjudication including their procedures,

administration of the social welfare legislation and land legislation, and

operation of social legislation like marriage and untouchability.

Finally, a word may be said about research methods in collecting

empirical data. It has been said : "In terms of a gross division, there are

only three methods of obtaining data in social research : one can ask

people questions; one can observe the behavior of persons, groups or

organisations, and their products or outcomes; or one can utilise existing

54. See. for instance. Rajya Sabha, Who's Who (1974). Also see. Socio-Economic

Background of Legislators in India (prepared by Research and Information Ser vice.

Lok Sabha Secretriat), 21 Jour. of Pari In! 23 (1975).

55. Supra note 44 at 31.

86

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

records or data already gathered for purposes other than one's own

research."56 The author is not trained in scientific methods of collecting

data and whatever little is said is based on common knowledge. A sociolegal researcher can get much valuable information by his own observations

and by studying existing records, (here the problem lies in getting access

to the records, since the government is extremely chary of permitting

anyone to see its records), but a note of warning may be sounded against

the method of collecting data by interview. Two broad types of data

collected through personal interviews are factual information and opinions

and views about a particular matter. About the limits of this method it

has been stated :

One of the limitations of the interview is the involvement of the

individual in the data he is reporting and the consequent likelihood

of bias. Even if we assume the individual to be in possession of

certain facts, he may withhold or distort them because to communicate them is threatening or in some manner destructive to

his ego. Thus, extremely deviant opinions and behavior, as well

as highly personal data, have long been suspect when obtained

by personal interviews....Another limitation on the scope of the

interview is the inability of the respondent to provide certain

types of information ....Memory bias is another factor which

renders the respondent unable to provide accurate information. 57

A few other limitations are the problems of communication process,

motivation of the respondent and his general ability, expertise of the

interviewer, the clarity of research goals, etc. Comparatively speaking,

an interviewer may be able to get information of much greater utility

when it relates to facts (but not relating to the respondent) than opinions

and views. We have to be extremely cautious with opinionated data

collecting. "Opinion" may mean the opinion of one ignorant individual

multiplied by a certain multiplier of the same quality. This is very aptly

demonstrated by an empirical study of the Indian Law Institute on

"Assessing the Degree and Depth of Acceptance of the System of Law

in India in terms of (i) Awareness, (ii) Value Compatibility, and (iii)

Pattern of Adaptation".58 Thus, one of the conclusions of the study is:

It is significant that those categories which have a lower level of

awareness also show a lower degree of acceptance of values

inherent in the present legal system. Their views regarding

56. Festinger and Katz (Ed.), Research Methods in the Behavioral Sciences 241

(1953).

57. Cannel and Kahn, "The Collection of Data by Interviewing", Id. at 330-31.

58. Unpublished (1967).

DOCTRINAL AND NONDOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCH

87

various procedural matters and problems and bottlenecks in the

legal system also show certain stable patterns. But it is amazing

that it is these categories which have the highest percentage of

those who say that the present legal system is "perfectly suitable"

for Indian society. This seems rather intriguing. But the

explanation perhaps is that those groups who have higher levels

of awareness of the legal system and who share the values

implicit in it to a larger extent, are at the same time more

conscious of its maladjustment with the overall socio-cultural

fabric.I?

This study in India was perhaps the first of its kind in the area of

socio-legal research, but it should create an awareness as to what a

socio-legal researcher should not do because of its utter failure to throw

any light on how the Indian legal system is to be improved or adapted

to the value patterns of the Indian people (apart from the value of the

study as signifying some of the too well-known weaknesses or defects

of the system).

To conclude, what is stated above is not to undermine the value of

the sociology oflaw (it can and ought to be used as a valuable supplement

or .~djunct to doctrinal research) but to warn against the over-optimism

of its advocates to expect too much from it. To borrow the language

from the International Legal Center monograph Law and Development,

"[I]t is important...to appreciate the special limits of our contemporary

development theories and to look to social science as an aid but not as

a panacea. "60

III. Certain heresies

The opportunity may be availed here to remove two heresies, It has

often been expressed that the legal community has not been concerned

with development (reference is usually made to economic development)

or shown sufficient awareness about it. This criticism seems to be

justified if the idea is to say that lawyers have not been associated with

the development plans and schemes by the planners and policy makers.

But it does not seem correct to say that lawyers have not concerned

themselves with the problems of development. The major problems,

created by development, requiring solution by lawyers have been the

growth of administrative power necessitating their control to avoid

arbitrariness, and equitable use and distribution of resources. That the

legal community has been deeply involved with these problems is amply

59. u. at 233.

60. Supra note 41 at 23.

88

LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

demonstrated by the inclusion of such courses in the legal pedagogy as

administrative law, labour law, governmental regulation of business,

company law and taxation. Even legal research is not lagging behind in

the area of development. A perusal of a few of the studies produced by

the Indian Law Institute should dispel any doubt in this regard. These

are:

(1) Contractual Remedies in Asian Countries; (2) Law of

International Trade Transactions; (3) Law Relating to Irrigation;

(4) Some Problems of Monopoly and Company Law; (5) Government Regulation of Private Enterprise; (6) Interstate Water

Disputes in India; (7) Law Relating to Flood Control in India; (8)

Law and Urbanisation in India; (9) Labour Law and Labour

Relations; (10) Property Relations in Independent India :

Constitutional and Legal Implications; (11) Cases and Materials

on Administrative Law in India; (12) Administrative Process

under the Essential Commodities Act; (13) Interstate Trade

Barriers and Sales Tax Laws in India; and (14) Administrative

Procedure Followed in Conciliation Proceedings under the

Industrial Disputes Act.

The second heresy pertains to the research work done by the Indian

Law Institute. It has been assumed in certain quarters that the Institute

has confined itself only to doctrinal research. Though it is true to say

that it has given priority to doctrinal research, yet it has not ignored

nondoctrinal research altogether. A number of instances of the latter

type of research can be cited : (1) Disciplinary Proceedings Against

Government Servants-A Case Study: This study is based on field work.

"The Institute's staff studied in detail sixty files (twenty each from the

years 1957, 1958 and 1959 which are consecutive files of closed cases

for these years) in connection with Part I and 150 files of closed cases

of the quinquennial period from 1955 in connection with Part II of the

study." This data was further supplemented by more general reports on

disposals provided by the department and by the information gathered

from responsible officers of the department. The research team also

attended formal disciplinary proceedings to gain insight into the operation

ofthe proceedings. (2) Administrative Procedure Fol/owed in Conciliation

Proceedings under the Industrial Disputes Act : This monograph is

based on a study of 373 cases of failure of conciliation and 421 cases

of settlements including award and mutual settlements to arrive at the

conclusions made in the book. (3) Interstate Water Disputes in India :

This study is again based on the actual case files of interstate water

disputes in India and interviews with the officials concerned at the level

of the Central Government. With the help of these files and interviews

DOCTRINAL AND NON-DOCTRINAL LEGAL RESEARCH

89

the Institute identified the issues requiring solution through law and also

the real reasons for failure to settle these disputes through methods other

than adjudication. (4) Interstate Trade Barriers and Sales Tax Laws in

India ": This study is based on economic data collected through a

questionnaire from the agencies concerned regarding the impact of the

present sales tax laws on interstate commerce. With the help of economic

data it found economic justification for a few of the provisions in the

Central Sales Tax Act. The study also recommended the creation of an

Interstate Taxation Co-ordination Council. This suggestion was

implemented to some extent by the government when in 1968 the Central

Government created four regional councils to discharge practically the

same functions as were suggested in case of the Interstate Taxation Coordination Council. (5) Presidential Assent to State Bil/s - A Case

Study: This study (published as articles in the Journal ofthe Indian Law

Institutes is based on a study of about 300 state Bills sent by the states

to the centre for presidential assent during the years 1956 to 1965. (6)

Assessing the Degree of Acceptance of the System of Law in India in

terms of (i) Awareness. (if) Value Compatibility. and (iii) Pattern of

Adaptation. Reference has already been made to this work in the earlier

pages.

Você também pode gostar

- Spechieo: Doctrinal and Non-Doctrinal Legal ResearchDocumento22 páginasSpechieo: Doctrinal and Non-Doctrinal Legal Researchdimpi aryaAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Research Methods: Doctrinal vs. Non-DoctrinalDocumento22 páginasLegal Research Methods: Doctrinal vs. Non-DoctrinalpavanAinda não há avaliações

- Critically Analysis The Reason of The Revival of Natural LawDocumento9 páginasCritically Analysis The Reason of The Revival of Natural LawrehgarAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence Question and AnswerDocumento29 páginasJurisprudence Question and AnswerIshrat ShaikhAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding the Concept of LawDocumento46 páginasUnderstanding the Concept of Lawmyhazman100% (1)

- Define Jurisprudence & Its Importance. Explain Law & Morality With ExamplesDocumento2 páginasDefine Jurisprudence & Its Importance. Explain Law & Morality With ExamplesApporv PalAinda não há avaliações

- Naeesha Halai IJLDAIDocumento9 páginasNaeesha Halai IJLDAIPhilemon AgustinoAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar 1-Natural LawDocumento14 páginasSeminar 1-Natural LawFrancis Njihia KaburuAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudential Schools of Thought by Geoffrey SoreDocumento17 páginasJurisprudential Schools of Thought by Geoffrey Soresore4jc100% (4)

- Relationship Between Law and Morality: Emerging Trends in IndiaDocumento19 páginasRelationship Between Law and Morality: Emerging Trends in Indiadiksha singhAinda não há avaliações

- Scope of JurisprudenceDocumento7 páginasScope of JurisprudenceAsad khanAinda não há avaliações

- Political Science 2 FinalDocumento19 páginasPolitical Science 2 FinalSOMYA YADAV0% (1)

- Judicial Precedents as an Effective and Reliable Source of LawDocumento7 páginasJudicial Precedents as an Effective and Reliable Source of LawShubham TanwarAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence, Concept and Philosophy of LawDocumento9 páginasJurisprudence, Concept and Philosophy of LawAnkita GhoshAinda não há avaliações

- Pankaj Sharma Sem VI 100 Jurisprudence IIDocumento20 páginasPankaj Sharma Sem VI 100 Jurisprudence IIPankaj SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence 1Documento71 páginasJurisprudence 1Ayushk5Ainda não há avaliações

- JurisprudenceDocumento44 páginasJurisprudenceamit HCSAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To LawDocumento7 páginasIntroduction To LawLogis ArrahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Endterm LTDocumento11 páginasEndterm LTMohammad Faisal TariqAinda não há avaliações

- Syed Muhammad Ibrahim Hassan JurisprudenceDocumento10 páginasSyed Muhammad Ibrahim Hassan JurisprudenceSyed Ibrahim HassanAinda não há avaliações

- A Project On Application of Jurisprudence in Social Life'Documento22 páginasA Project On Application of Jurisprudence in Social Life'Vyas NikhilAinda não há avaliações

- Meaning, Functions and Theories of LawDocumento10 páginasMeaning, Functions and Theories of LawMayank KhaitanAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of SubstantiveDocumento32 páginasThe Role of SubstantiveSophiaFrancescaEspinosaAinda não há avaliações

- Law As An Instrument of Social EngineeringDocumento15 páginasLaw As An Instrument of Social EngineeringChitraksh MahajanAinda não há avaliações

- Application of Social Research Findings in The Field of Law: TopicDocumento14 páginasApplication of Social Research Findings in The Field of Law: TopicSingh HarmanAinda não há avaliações

- IA JurisprudenceUnit1Documento20 páginasIA JurisprudenceUnit1Fuwaad SaitAinda não há avaliações

- Scope of Jurisprudence - Ritika Vohra: Abstract: Jurisprudence Comes From The Latin Word Jurisprudentia' Which Means TheDocumento7 páginasScope of Jurisprudence - Ritika Vohra: Abstract: Jurisprudence Comes From The Latin Word Jurisprudentia' Which Means TheHarsh DixitAinda não há avaliações

- JurisprudenceDocumento8 páginasJurisprudenceSuhani ChughAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence NotesDocumento21 páginasJurisprudence NotesMobile Backup100% (3)

- JurisprudenceDocumento45 páginasJurisprudenceNagendra Muniyappa83% (18)

- Jurisprudence NotesDocumento106 páginasJurisprudence NotesDeepak Ramesh100% (1)

- Law and MoralityDocumento10 páginasLaw and MoralitySwathi SwazzAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of Sources of LawDocumento16 páginasAnalysis of Sources of LawRishabh Jain100% (1)

- Law N Morality - Pol SC ProjctDocumento25 páginasLaw N Morality - Pol SC ProjctNitesh JindalAinda não há avaliações

- Nature and Scope of JurisprudenceDocumento7 páginasNature and Scope of JurisprudencetejAinda não há avaliações

- 007juris ReportDocumento2 páginas007juris ReportReeya PrakashAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence: Arvind Nath Tripathi DsnluDocumento15 páginasJurisprudence: Arvind Nath Tripathi Dsnluvijay srinivasAinda não há avaliações

- Juris PrudeDocumento15 páginasJuris PrudeUPAMA NANDYAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence Assignment - NATURE AND SCOPE OF JURISPRUDENCEDocumento45 páginasJurisprudence Assignment - NATURE AND SCOPE OF JURISPRUDENCEprakshiAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence Notes - Nature and Scope of JurisprudenceDocumento11 páginasJurisprudence Notes - Nature and Scope of JurisprudenceMoniruzzaman Juror100% (4)

- Pankaj Sharma Sem VI 100 Jurisprudence IIDocumento20 páginasPankaj Sharma Sem VI 100 Jurisprudence IIPankaj SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- DGGHHDocumento64 páginasDGGHHAnkur bhattAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence Types and BenefitsDocumento7 páginasJurisprudence Types and BenefitsTahir Siddique100% (2)

- The Powerful Judiciary and Rule of Law in The PhilippinesDocumento18 páginasThe Powerful Judiciary and Rule of Law in The PhilippinesdbaksjbfkasjdbAinda não há avaliações

- Final Sources of LawDocumento21 páginasFinal Sources of LawDoyel MehtaAinda não há avaliações

- Wa0000.Documento6 páginasWa0000.ariha0024Ainda não há avaliações

- Tohijul Admin Law FinalDocumento18 páginasTohijul Admin Law FinalSubhankar AdhikaryAinda não há avaliações

- Kinds of Ownership PDFDocumento40 páginasKinds of Ownership PDFseshu187100% (1)

- Introduction To Law, Morrocan CaseDocumento38 páginasIntroduction To Law, Morrocan CaseOussama RaourahiAinda não há avaliações

- 416374863-Jurisprudence-NotesDocumento16 páginas416374863-Jurisprudence-Notesswamini.k65Ainda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence NotesDocumento16 páginasJurisprudence NotesAnkur Bhatt100% (5)

- 1906 Abhishek KumarDocumento22 páginas1906 Abhishek KumarAbhishek KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Natural Law Theory in JurisprudenceDocumento13 páginasNatural Law Theory in Jurisprudencesarayu alluAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Rights PDFDocumento19 páginasLegal Rights PDFFaith DiasAinda não há avaliações

- Unit-1 Introduction To Legal Method: Definition of LawDocumento55 páginasUnit-1 Introduction To Legal Method: Definition of Lawkanav singhAinda não há avaliações

- Interpreting Procedure Established by Law WithDocumento5 páginasInterpreting Procedure Established by Law WithpremsinghAinda não há avaliações

- English JurisprudenceDocumento20 páginasEnglish JurisprudenceLaw LecturesAinda não há avaliações

- Art of Being A JudgeDocumento16 páginasArt of Being A Judgesaif aliAinda não há avaliações

- Corpus Juris: The Order of the Defender of ArabiaNo EverandCorpus Juris: The Order of the Defender of ArabiaAinda não há avaliações

- Operation Manual of AC001Documento11 páginasOperation Manual of AC001Kunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Carpen ToolsDocumento9 páginasCarpen Toolsakash10107Ainda não há avaliações

- Uttar Pradesh Electric VehiclesDocumento13 páginasUttar Pradesh Electric VehiclesSubhashiniAinda não há avaliações

- Cremica Products Institutional Price ListDocumento3 páginasCremica Products Institutional Price ListKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- List of Swadeshi or Indian Products - Great of India - Made in India - Swadeshi - Make in India - Great of IndiaDocumento5 páginasList of Swadeshi or Indian Products - Great of India - Made in India - Swadeshi - Make in India - Great of IndiaKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Hridyansh Kushwaha PDFDocumento9 páginasHridyansh Kushwaha PDFKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- University Grants Commission Net BureauDocumento4 páginasUniversity Grants Commission Net Bureaumnb11augAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Terms Cafe Central PDFDocumento5 páginasLegal Terms Cafe Central PDFKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- UGC NET Teaching & Research Aptitude SyllabusDocumento4 páginasUGC NET Teaching & Research Aptitude Syllabusmnb11augAinda não há avaliações

- Courts Cannot Interfere in The Policy Decisions of The GovernmentDocumento3 páginasCourts Cannot Interfere in The Policy Decisions of The GovernmentKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Planning Where We Are in Place and Time Grade 3 4 PDFDocumento4 páginasPlanning Where We Are in Place and Time Grade 3 4 PDFKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- VKE Academic Honesty Policy-June16 PDFDocumento18 páginasVKE Academic Honesty Policy-June16 PDFKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Competition Law AssignmentDocumento19 páginasCompetition Law AssignmentKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Liquidation of CompanyDocumento29 páginasLiquidation of CompanyKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Courts Cannot Interfere in The Policy Decisions of The GovernmentDocumento3 páginasCourts Cannot Interfere in The Policy Decisions of The GovernmentKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture On Insurance LawDocumento8 páginasLecture On Insurance LawGianaAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Terms Cafe Central PDFDocumento5 páginasLegal Terms Cafe Central PDFKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Why Free Trade Is More Important Than Fair TradeDocumento5 páginasWhy Free Trade Is More Important Than Fair TradeKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Issuance of Certificate by Banks U - S SecDocumento4 páginasIssuance of Certificate by Banks U - S SecKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Competition Appellate Tribunal Hear Appeals Against CCI OrdersDocumento1 páginaCompetition Appellate Tribunal Hear Appeals Against CCI OrdersKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Why Free Trade Is More Important Than Fair TradeDocumento5 páginasWhy Free Trade Is More Important Than Fair TradeKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- COMPATDocumento11 páginasCOMPATKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- MBBS BULLETIN 2016 Dated 15 Aug 2016 PDFDocumento41 páginasMBBS BULLETIN 2016 Dated 15 Aug 2016 PDFKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Three Generations of Human RightDocumento2 páginasThree Generations of Human RightKunal Singh100% (1)

- Telecom Sector Thesis 01Documento161 páginasTelecom Sector Thesis 01Kunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Legal Research PDFDocumento46 páginasIndian Legal Research PDFKunal Singh67% (3)

- Nature and Scope of Jurisprudence ExplainedDocumento40 páginasNature and Scope of Jurisprudence ExplainedKunal Singh86% (21)

- Right To DieDocumento10 páginasRight To DieKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- ILI 1 Year LLMDocumento9 páginasILI 1 Year LLMKunal SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Beth Mukui Gretsa University-Past TenseDocumento41 páginasBeth Mukui Gretsa University-Past TenseDenis MuiruriAinda não há avaliações

- Drummond. Philo Judaeus Or, The Jewish-Alexandrian Philosophy in Its Development and Completion. 1888. Volume 1.Documento378 páginasDrummond. Philo Judaeus Or, The Jewish-Alexandrian Philosophy in Its Development and Completion. 1888. Volume 1.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisAinda não há avaliações

- Competence Based Curriculum For Rwanda Education Board (Reb)Documento124 páginasCompetence Based Curriculum For Rwanda Education Board (Reb)Ngendahayo Samson79% (24)

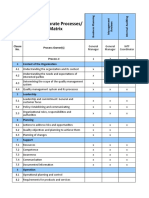

- IATF 16949 Corporate Processes/ Clause Matrix: Process Owner(s) Process # Context of The Organization Clause NoDocumento6 páginasIATF 16949 Corporate Processes/ Clause Matrix: Process Owner(s) Process # Context of The Organization Clause NoshekarAinda não há avaliações

- Syllabus - Environmental Technology 23-08-11Documento2 páginasSyllabus - Environmental Technology 23-08-11AmruthRaj 'Ambu'Ainda não há avaliações

- Examination of ConscienceDocumento2 páginasExamination of ConscienceBrian2589Ainda não há avaliações

- Project CostingDocumento10 páginasProject CostingDanish JamaliAinda não há avaliações

- WHT Rates Tax Year 2023-24 - 230630 - 222611Documento2 páginasWHT Rates Tax Year 2023-24 - 230630 - 222611Ammad ArifAinda não há avaliações

- MATERIAL # 9 - (Code of Ethics) Code of EthicsDocumento6 páginasMATERIAL # 9 - (Code of Ethics) Code of EthicsGlessey Mae Baito LuvidicaAinda não há avaliações

- Method Statement For Steel TankDocumento16 páginasMethod Statement For Steel TankJOHNK25% (4)

- The Effect of Smartphones On Work Life Balance-LibreDocumento15 páginasThe Effect of Smartphones On Work Life Balance-LibreNeelanjana RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Coca Cola Company SWOT AnalysisDocumento5 páginasCoca Cola Company SWOT AnalysismagdalineAinda não há avaliações

- 2019 Bar Reviewer Lagel Ethics PDFDocumento110 páginas2019 Bar Reviewer Lagel Ethics PDFAnne Laraga Luansing100% (1)

- GT Essays makkarIELTSDocumento233 páginasGT Essays makkarIELTSa “aamir” Siddiqui100% (1)

- Who Is A Ship Chandler?: Origin and Importance of Ship Chandelling ServicesDocumento3 páginasWho Is A Ship Chandler?: Origin and Importance of Ship Chandelling ServicesPaul Abonita0% (1)

- Kowloon City Government Hostel 2Documento1 páginaKowloon City Government Hostel 2sanaAinda não há avaliações

- Checklist (Amp)Documento7 páginasChecklist (Amp)Mich PradoAinda não há avaliações

- The Story of AbrahamDocumento3 páginasThe Story of AbrahamKaterina PetrovaAinda não há avaliações

- Ackowledgement of Risks and Waiver of Liability: Specify School Activities I.E. Practice Teaching, OJT, EtcDocumento1 páginaAckowledgement of Risks and Waiver of Liability: Specify School Activities I.E. Practice Teaching, OJT, EtcMAGDAR JAMIH ELIASAinda não há avaliações

- Control Activities 5Documento4 páginasControl Activities 5Trisha Mae BahandeAinda não há avaliações

- Distilleries & BaveriesDocumento8 páginasDistilleries & Baveriespreyog Equipments100% (1)

- Oppression of The Local Population by Quing RulersDocumento36 páginasOppression of The Local Population by Quing RulersAsema BayamanovaAinda não há avaliações

- Brunei Legal System - Chapter 2Documento4 páginasBrunei Legal System - Chapter 2isabella1113100% (1)

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocumento5 páginas(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowAinda não há avaliações

- Panos London 01 Who Rules The InternetDocumento6 páginasPanos London 01 Who Rules The InternetMurali ShanmugavelanAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Expatriate ManagementDocumento12 páginasSustainable Expatriate ManagementLee JordanAinda não há avaliações

- Abakada Guro Party List Case DigestDocumento2 páginasAbakada Guro Party List Case DigestCarmelito Dante Clabisellas100% (1)

- Environment Clearance To L & T Tech Park PVT Ltd.Documento9 páginasEnvironment Clearance To L & T Tech Park PVT Ltd.nairfurnitureAinda não há avaliações

- Design Your Own Website With WordPress (Pdfstuff - Blogspot.com)Documento135 páginasDesign Your Own Website With WordPress (Pdfstuff - Blogspot.com)Abubaker ShinwariAinda não há avaliações

- Minoan Foreign TradeDocumento28 páginasMinoan Foreign Tradeehayter7100% (1)