Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Yuhas 2012 Scientific American Mind

Enviado por

Koketso PatrickDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Yuhas 2012 Scientific American Mind

Enviado por

Koketso PatrickDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

yuhas

So You Want to Be a Genius

When it comes to cultivating genius, talent matters, but motivation may matter more By Daisy Yuhas

ot motivation? Without it, the long, difficult hours of

p ractice that elevate some people above the rest are

excruciating. But where does such stamina come from,

and can we have some, too? Psychologists have identified three

critical elements that support motivation, all of which you can

tweak to your benefit.

Autonomy

Whether you pursue an activity for its own sake or because

external forces compel you, psychologists Edward L. Deci and

Richard M. Ryan of the University of Rochester argue that you

gain motivation when you feel in charge. In evaluations of students, athletes and employees, the researchers have found that

the perception of autonomy predicts the energy with which individuals pursue a goal.

In 2006 Deci and Ryan, with psychologist Arlen C. Moller,

designed several experiments to evaluate the effects of feeling

controlled versus self-directed. They found that subjects given

the opportunity to select a course of action based on their own

opinions (for example, giving a speech for or against teaching

psychology in high school) persisted longer in a subsequent

puzzle-solving activity than participants who were either given

no choice or pressured to select one side over another. Deci and

Ryan posit that acting under duress is taxing, whereas pursuing

a task you endorse is energizing.

Competence

chologists at the Democritus University of Thrace and the University of Thessaly in Greece surveyed 882 students on their

a ttitudes and engagement with athletics during a two-year

period. They found a strong link between a students sense of

prowess and his or her desire to pursue sports. The connection

worked in both directions practice made students more likely

to consider themselves competent, and a sense of competence

strongly predicted that they would engage in athletic activity.

Similar studies in music and academics bolster these findings.

Carol S. Dweck, a psychologist at Stanford University, has

shown that competence comes from recognizing the basis of accomplishment. In numerous studies, she has found that those

who credit innate talents rather than hard work give up more

easily when facing a novel challenge because they assume it

exceeds their ability. Believing that effort fosters excellence can

inspire you to keep learning.

The next time you struggle to lace up your sneakers or park

yourself at the piano bench, ask yourself what is missing. Often

the answer lies in one of these three areas feeling forced, finding an activity pointless or doubting your capabilities. Tackling

such sources of resistance can strengthen your resolve. The

choice, of course, is yours.

As you devote more time to an activity, you notice your skills

improve, and you gain a sense of competence. In 2006 psy

Daisy Yuhas is a science writer based in New York City.

Value

K r i s t e n G e r ac i G e t t y I m a g e s

Practice makes perfect, but finding the personal wherewithal to

start can be daunting. Proved techniques can help build motivation.

Motivation also blossoms when you stay true to your beliefs

and values. Assigning value to an activity can restore ones sense

of autonomy, a finding of great interest to educators. In a 2010

review article, University of Maryland psychologists Allan Wigfield

and Jenna Cambria noted that several studies have found a positive correlation between valuing a subject in school and a students willingness to investigate a question independently.

The good news is that value can be modified. In 2009 University of Virginia psychologist Christopher S. Hulleman described a semester-long intervention in which one group of high

school students wrote about how science related to their lives

and another group simply summarized what they had learned in

science class. The most striking results came from students

with low expectations of their performance. Those who described the importance of science in their lives improved their

grades more and reported greater interest than similar students

in the summary-writing group. In short, reflecting on why an activity is meaningful could make you more invested in it.

w w w. S c i e nti f i c A m e r i c an .c o m/M in d s c i e n t i f i c am e r i c a n m i n d 49

MiQ612Yuha4p.indd 49

9/7/12 6:09 PM

Você também pode gostar

- Edr Designguidelines Hvac Simulation 2ed PDFDocumento64 páginasEdr Designguidelines Hvac Simulation 2ed PDFKoketso PatrickAinda não há avaliações

- FEMP Continuous CX GuidebookDocumento164 páginasFEMP Continuous CX GuidebookKoketso PatrickAinda não há avaliações

- Classification of PDEs by Hoffmann and ChiangDocumento26 páginasClassification of PDEs by Hoffmann and ChiangKoketso PatrickAinda não há avaliações

- Constant Mean CurvatureDocumento100 páginasConstant Mean CurvatureKoketso PatrickAinda não há avaliações

- Time Dependent Problems and Difference MethodsDocumento657 páginasTime Dependent Problems and Difference MethodsKoketso PatrickAinda não há avaliações

- DetachmentDocumento6 páginasDetachmentKoketso Patrick100% (1)

- Purpose, and The Service You Came To Offer Humanity Is Called Your Life's WorkDocumento5 páginasPurpose, and The Service You Came To Offer Humanity Is Called Your Life's WorkKoketso PatrickAinda não há avaliações

- End-Life Behavior of Incinerated NanoparticlesDocumento16 páginasEnd-Life Behavior of Incinerated NanoparticlesKoketso PatrickAinda não há avaliações

- Shomate EquationDocumento2 páginasShomate EquationKoketso Patrick100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- 7 Philosophies of EducationDocumento2 páginas7 Philosophies of Educationmei rose puyat50% (6)

- Persepsi Mahasiswa Mengenai Tingkat Pelaksanaan Problem Based Learning (PBL) Pada Tutorial Di FK Universitas HKBP NommensenDocumento9 páginasPersepsi Mahasiswa Mengenai Tingkat Pelaksanaan Problem Based Learning (PBL) Pada Tutorial Di FK Universitas HKBP NommensenMaikel PasaribuAinda não há avaliações

- Byelawsupdated21 1 13 PDFDocumento86 páginasByelawsupdated21 1 13 PDFVijay KsheresagarAinda não há avaliações

- 30 Habits of Highly Effective TeachersDocumento8 páginas30 Habits of Highly Effective TeachersYves StutzAinda não há avaliações

- SAP Africa Launches South African Chapter of SAP Skills For Africa InitiativeDocumento2 páginasSAP Africa Launches South African Chapter of SAP Skills For Africa InitiativeNikk SmitAinda não há avaliações

- CHAPTER 1 LalaDocumento12 páginasCHAPTER 1 LalaIvan LedesmaAinda não há avaliações

- Interdisciplinary Teaching and LearningDocumento23 páginasInterdisciplinary Teaching and LearningYan MoistnadoAinda não há avaliações

- SWRB Social Work Practice Competencies - Self-Assessment 3 FinalDocumento3 páginasSWRB Social Work Practice Competencies - Self-Assessment 3 Finalapi-291442969Ainda não há avaliações

- SPFSC English SyllabusDocumento63 páginasSPFSC English SyllabusLi Ann Waqadau RaunacibiAinda não há avaliações

- DM 471 S. 2021 Division Memorandum On 5th CARE CON 12162021 1Documento42 páginasDM 471 S. 2021 Division Memorandum On 5th CARE CON 12162021 1Nheng M. BlancoAinda não há avaliações

- Peace Corps Environmental Education in The Schools: Creating A Program That Works - August 1993 - M0044Documento514 páginasPeace Corps Environmental Education in The Schools: Creating A Program That Works - August 1993 - M0044Accessible Journal Media: Peace Corps Documents100% (1)

- NEW ResumeDocumento1 páginaNEW Resumeamy-lovejoyAinda não há avaliações

- School InformationDocumento6 páginasSchool Informationapi-283614707Ainda não há avaliações

- Find Someone Who PDFDocumento2 páginasFind Someone Who PDFYurany MonsalveAinda não há avaliações

- Curriculum Development (EDU 402) Lecture No 1 Introduction To Curriculum Topic 1: IntroductionDocumento143 páginasCurriculum Development (EDU 402) Lecture No 1 Introduction To Curriculum Topic 1: Introductionallow allAinda não há avaliações

- Teaching SpeakingDocumento18 páginasTeaching Speaking39 - 006 - Imran Hossain ReyadhAinda não há avaliações

- Capinpin Research PaperDocumento16 páginasCapinpin Research Paperfrancine.malit24Ainda não há avaliações

- LP - Our Home, Our EarthDocumento2 páginasLP - Our Home, Our EarthJessabel ColumnaAinda não há avaliações

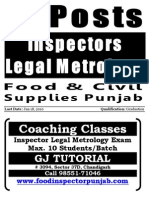

- Application Form: Inspector Legal Metrology PunjabDocumento6 páginasApplication Form: Inspector Legal Metrology PunjabSarbjit SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Compilation in Facilitating Learning 224Documento55 páginasCompilation in Facilitating Learning 224KM EtalsedAinda não há avaliações

- Phonetics Exercises and ExplanationDocumento15 páginasPhonetics Exercises and ExplanationMary JamesAinda não há avaliações

- Semi Detailed ICT Day 4Documento4 páginasSemi Detailed ICT Day 4nissAinda não há avaliações

- Scatter Kindness Asca TemplateDocumento6 páginasScatter Kindness Asca Templateapi-248791381100% (1)

- Q4 Week 1 Math 7Documento4 páginasQ4 Week 1 Math 7Meralyn Puaque BustamanteAinda não há avaliações

- FS 2 Ep 9Documento5 páginasFS 2 Ep 9Josirene Lariosa100% (2)

- PSC2 Form - Rev. 2016 PDFDocumento4 páginasPSC2 Form - Rev. 2016 PDFdismasAinda não há avaliações

- Psychological Wisdom Research: Commonalities and Differences in A Growing Field Annual Review of PsychologyDocumento23 páginasPsychological Wisdom Research: Commonalities and Differences in A Growing Field Annual Review of PsychologySuvrata Dahiya PilaniaAinda não há avaliações

- Proposal For Construction of Parapet WallDocumento6 páginasProposal For Construction of Parapet WallHisbullah KLAinda não há avaliações

- Number 5 Lesson PlanDocumento3 páginasNumber 5 Lesson Planapi-300212612Ainda não há avaliações

- Ruby BridgesDocumento15 páginasRuby BridgesEnkelena AliajAinda não há avaliações