Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Shatavari (Asparagus Racemosus), Jivanti (Leptadenia Reticulata) and Methi (Trigonella Foenum-Graecum) : The Herbal Galactogogues For Ruminants

Enviado por

Sanjay C. ParmarTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Shatavari (Asparagus Racemosus), Jivanti (Leptadenia Reticulata) and Methi (Trigonella Foenum-Graecum) : The Herbal Galactogogues For Ruminants

Enviado por

Sanjay C. ParmarDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Patel et al. 2016/J. Livestock Sci.

7: 231-237

Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus), Jivanti (Leptadenia

reticulata) and Methi (Trigonella foenum-graecum): the

herbal galactogogues for ruminants

V.K. Patel1*, A. Joshi1, R.P. Kalma1, S.C. Parmar2, S.V. Damor1 and

K.R. Chaudhary1

1

College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, Sardarkrushinagar Dantiwada Agricultural University,

Sardarkrushinagar 385506, Gujarat, 2College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, Anand Agricultural

University, Anand 388001, Gujarat, India

*Corresponding authors E-mail: drvikrampatel2012@gmail.com

Journal of Livestock Science (ISSN online 2277-6214) 7: 231-237

Received on 20/7/2016; Accepted on 9/9/2016

Abstract

Use of herbal galactogogue for safe and sound milk production is prerequisite now a days because of

increasing the demand for organic food and the ban on the use of certain antibiotics, harmful residual effects and

cost effectiveness in the livestock feed. Herbals inclusion in the diet should be encouraged to enhance animals

performance, improve feed efficiency, maintain health and alleviate adverse effect of environmental stress.

Galactogogues stimulate the activity of alveolar tissue and increase the secretory activity and thereby restore and

regulate milk yield. This review introduces three effective herbal galactagogues named Shatavari (Asparagus

racemosus), Jivanti (Leptadenia reticulata) and Methi (Trigonella foenum-graecum) as feed additive and its

effect on livestock performance.

Keywords: galactogogue, A. racemosus, L. reticulata, T. foenum-graecum

231

Patel et al. 2016/J. Livestock Sci. 7: 231-237

Introduction

Livestock sector plays a vital role in the rural economy as providing family income and generating

gainful employment in the rural sector. Livestock contributes 3.9 % in total GDP during the year of 2013-14.

India is leading country in total milk production. Milk production in India is 137.7 million tonnes in 2013-14

and per capita availability is 307 g/day in 2014-15 (DADF, 2015). During the last two decades, India has

emerged as worlds top most nations in the dairy sector and has witnessed rapid development in the milk

production. On other hands, the productivity of dairy animals in India is very low because of various factors like

underfeeding, malnutrition, various diseases, stress, etc which hamper the economy of the dairy industry. With

the demand for organic food and ban on the use of certain antibiotics, harmful residual effects and cost

effectiveness in the livestock feed, the search for alternative feed additives has become the necessity of the day.

Herbal feed additives could either effect feeding pattern, or effect the growth of favourable microorganisms in

the rumen, or stimulate the secretion of different digestive enzymes, which in turn may improve the efficiency

of nutrients utilization or stimulate the milk secreting tissue in the mammary glands, resulting in improved

productive and reproductive performance of dairy animals (Bakshi and Wadhwa, 2000). A medicinal herb has

properties to improve digestibility, antibacterial, immunostimulation, coccidiostatic, anthelmintic, antiviral or

antioxidative (Uegaki et al., 2001).

Herbals are concentrated foods those provide vitamins, minerals and other nutrients that sustain and

strengthen the human and animal body. Indian history is very rich in herbal medicine and one of the oldest

surviving systems of healthcare in the world known as ayurveda. Ayurveda is a natural therapy and totally based

on herbs. These herbs were being used since pre-vedic time because they were safe to use, cheap and easily

available, has no side effect and no residual effect in milk (Krishna et al., 2005). So, their inclusion in the diet

should be encouraged to enhance animals performance, improve feed efficiency, maintain health and alleviate

adverse effect of environmental stress. Traditional herbal medicines in veterinary practice have a large potential

as an alternate therapy. A galactogogue is a substance that promotes lactation in dairy animals. It may be

synthetic, plant-derived, or endogenous. They act through exerting an influence on an adreno-hypothalamohypophyseal-gonadal axis by inhibiting hypothalamic dopaminergic receptors or by inhibiting dopamine

producing neurons. These medications increase prolactin secretion by antagonizing dopamine receptors (Gabay,

2002). Galactogogues stimulate the activity of alveolar tissue and raise the secretory activity and thereby restore

and regulate milk yield (Ravikumar and Bhagwat, 2008). The animal production can be enhanced by using

different herbals as a component of animal feed. According to Bakshi et al. (2004), now a days herbal plants

are broadly used as animal feed additives, having galactogogue properties like Shatavari (Asparagus

racemosus), Jivanti (Leptadenia reticulata) and Methi (Trigonella foenum).

Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus)

Asparagus racemosus is most frequently used in indigenous medicine. The name Shatavari means

curer of a hundred diseases (shat means hundred and vari means curer) and it is also known as Satavar and

Shatmuli. The leaves are alike pine needles, small and uniform and the flowers are white and have small spikes.

It is a common species of asparagus under Liliaceae family distributed throughout India with 1 to 2 m in height.

The genuses Asparagus contains about 300 species around the world and out of these 22 species are found in the

India. Asparagus racemosus is the one most commonly used herb in traditional medicine due to the presence of

steroidal saponins and sapogenins in various parts of a plant (Krishana et al., 2005). Traditionally it is used as a

health tonic and common Indian home remedy used as a rejuvenator, promoter of strength, breast milk and

semen. It is also used for cough, dyspepsia, edema, rheumatism, chronic fevers, aphrodisiac, cooling tonic

antispasmodic, diarrhea and dysentery. It is also used for enhancing milk production in freshly parturient and

lactating woman (Chopra and Simon, 2000). The general pharmacology of shatavari are galactogogue and

mammogenic, it enhances the blood prolactin level and stimulazes the cellular division of mammary gland

(Kumar et al., 2008).

Choudhary and Kar (1992) recorded that shatavari root is rich source of minerals and it contains macro

minerals such as Ca, Mg, K and Fe having concentration of 0.22, 0.40, 2.50 and 0.01 g/100g, respectively and

micro minerals such as Cu, Zn, Mn, Co and Cr having concentration of 5.29, 53.15, 19.98, 22.0 and 1.81 /gm,

respectively. Berhane and Singh (2000) reported the DM, CP, EE, CF, Ash and NFE of Shatavari root powder

to be 91.0, 3.85, 0.66, 8.32, 13.15 and 74.02 percent, respectively. Shatavari root contains 4.60 to 6.10 per cent

protein, 36.80 to 47.50 per cent carbohydrates, 3.10 to 5.20 mg/g phenols, 4.80 to 5.10 mg/g tannins, 4.10 per

cent saponin and 6.50 to 7.40 per cent ash (Mishra et al., 2005). Visavadiya and Narasimhacharya (2005)

estimated the presence of phyto-components in Shatavari root such as phytosterols (0.79%), saponin (8.83%),

polyphenols (1.69%), flavonoids (0.48%) and total ascorbic acid (0.76%). Supplementation of Galactin (50

g/d/animal), a Shatavari based polyherbal galactogogue in lactating crossbred cows had improved milk

production (Ramesh, 2000). Feeding herbal formulation containing 25 per cent Shatavari enhanced milk

production (25.10%) and an also significant improvement in daily milk yield in buffaloes and crossbred cows. A

232

Patel et al. 2016/J. Livestock Sci. 7: 231-237

response of supplementation of Shatavari in buffaloes is higher than cows (Somkuwar et al., 2005).

Supplementation of Shatavari @ 50 g per day in 10 lactating cattle and buffaloes with concentrate for the period

of 60 days results in the increased milk production in buffaloes and cows by 9.90 per cent (0.8 0.34 kg/day)

and 12.72 per cent (1.32 0.15 kg/day), respectively (Tanwar et al., 2008). Polyherbal supplementation

containing Shatavari @ 150 to 200 mg/kg body weight in Karanfries cows significantly improve fat, protein,

lactose and SNF yield during supplementation, residual and post- residual period in fed groups than control

(Sharma, 2010). Feeding of Shatavari in Murrah buffaloes during their transition and post-partum period

increased 10.68 per cent milk production (Singh et al., 2012). Supplementation of Milkplus, a Shatavari based

herbal preparation enhanced the milk yield from 8.26 to 10.11 liters/day in crossbred cattle (Sukanya et al.,

2014).

Fig. 1: Shatavari plant (A. racemosus)

Fig. 2: Shatavari root (A. racemosus)

(Source: http://www.homeremediess.com/medicinal-plants-shatavari-benefits)

Fig. 3: Jivanti plant (L. reticulata)

Fig. 4: Jivanti root (L. reticulata)

(Source: http://www.alwaysayurveda.com/leptadenia-reticulata)

Jivanti (Leptadenia reticulata)

Leptadenia reticulata is also known as Jivanti (or Jiwanti) because of its nourishing property for every

part of the body. Jivanti specially corrects the metabolism, digestive system and enhance the health status of the

body. Indian synonyms of Jivanti are Bhadjivai (in Bengali), Methiododi or Dodi (Gujarati), Dori (Hindi),

Hiriyahalle (Kannada), Haranvel (Marathi), Jivanti (Sanskrit) and Kalasa (Telugu). Leptadenia reticulate is

belongs to family Asclepiadaceae commonly known as Jivanti. It is distributed in subtropical and tropical parts

of Asia and Africa, Burma, Sri Lanka, Malayan peninsula, Philippines, Mauritius and Madagascar. In India,

Jivanti is found in Gujarat, Punjab, Himalayan ranges, South India, Sikkim, Deccan and Karnataka. The shape

of leaves varies from ovate to cordate, 4 to 8 cm long, 2 to 5.5 cm broad, glabrous above and pubescent below.

The roots are very rough, white with longitudinal ridges and furrows and in transverse section the wide cork,

lignified stone cell layers and medullary rays can be seen and its size varies from 3 to 10 cm in length and 1.5 to

5 cm in diameter. Leptadenia reticulata is considered to be a tonic (Rasayana) drug and is used to strengthen,

nourish and rejuvenate the body (Kirtikar and Basu, 1993). It can be used in treating various body aliments like

bleeding disorders, burning sensitivity of the body, pyrexia, cough, dehydration, weak vision and colitis. It

233

Patel et al. 2016/J. Livestock Sci. 7: 231-237

possesses the aphrodisiac, astringent, galactogogue, diuretic and used as a tonic in debility (Sonara et al., 2013).

Its lactogenic effect has been reported in various domestic animals (Dadarkar et al., 2005). Extracts of roots and

leaves of the plant act as antibacterial, antifungal agent and anti abortificient activity (Patel and Dantwala,

1958). Plant possesses the vigorous lactogenic, anabolic and galactogogue effect (Ravishankar and Shukla,

2007).

Leptadenia reticulata contain -amyrin, -amyrin, ferulic acid, luteolin, diosmetin, rutin, -sitosterol,

stigmasterol and hentriacontanol (Krishna et al., 1975). Srivastav et al. (1994) reported that leaf of Jivanti

contains resins, albuminous, Ca oxalate glucose, carbohydrate and tartaric acid. Hewageegana et al. (2014)

reported that the Leptadenia reticulata consist of total ash (16.61%), acid insoluble ash (2.80%), water soluble

ash (5.90%), protein (35.80%), crude fat (2.80%), carbohydrates (23.40%), dietary fibre (14.23%), magnesium

(1.50%), iron (0.03%) and calcium (0.97%). Supplementation of leptaden tablet consists of Jivanti in buffaloes

significantly increased milk yield in field condition (Moulvi, 1963). Feeding of Galactin-Vet bolus in lactating

cows improve milk yield of 6.06 per cent during the treatment and 5.48 per cent following the treatment

(Sridhar and Bhagawat, 2007). Supplementation of Jivanti in kankrej cows there was non-significantly higher

fat yield than control during and post supplementation period (Jain, 2016).

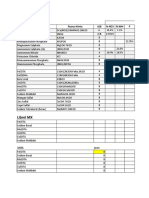

Table 1: Biochemical constituents in root of Shatavari (A. racemosus), leaf/root of Jivanti (L. reticulata) and

seed of Methi (T. foenum-graecum).

Biochemical

Shatavari

Jivanti

Methi

References

constituents

Protein (%)

4.60 - 6.10

35.80

20.0 - 30.0

Mishra et al. (2005)

Hewageegana et al. (2014)

Carbohydrates (%)

36.80 - 47.50

23.40

45.0 - 60.0

Mehrafarin et al. (2010)

Hewageegana et al. (2014)

Crude Fat (%)

2.80

6.53

Sinha et al. (2015)

Phenol (%)

3.10 - 5.20

Mishra et al. (2005)

Tannin (%)

4.80 - 5.10

Mishra et al. (2005)

Saponin (%)

4.10

0.60 - 1.70

Mehrafarin et al. (2010)

Total Ash (%)

13.15

16.61

Berhane and Singh (2000)

Calcium (g/100g)

0.22

0.97

Hewageegana et al. (2014)

Magnesium (g/100g)

0.40

1.50

Potassium (g/100g)

2.50

Choudhary and Kar (1992)

Choudhary and Kar (1992)

Iron (g/100g)

0.01

0.03

Hewageegana et al. (2014)

Copper (/gm)

5.29

Zinc (/gm)

53.15

Manganese (/gm)

19.98

Choudhary and Kar (1992)

Cobalt (/gm)

22.00

Chromium (/gm)

1.81

-

Methi (Trigonella foenum-graecum)

Fenugreek is a leguminous herb belonging to a fabaceae family that is cultivated in numerous parts

of the world predominantly in India, Middle East, North Africa and South Europe. It is cultivated worldwide as

a semi-arid crop. It is commonly known as Methi. The seeds are used as a spice and the leaves are consumed as

a green vegetable, which are bitter in taste and have been in use for over 2500 years. These seeds are small in

size, golden yellow colour and have four faced stone like structure. Raw fenugreek seeds are bitter in taste due

to the existence of bitter saponins, which limit their acceptability in foods. India is a major producer and also a

chief consumer of fenugreek for cooking uses and medicinal applications (Agrawal et al., 2015). In different

languages, it has different names like Fenugrec (French), Methi (Hindi), Pazhitnik (Russian), Fienogreco

(Italian), Alholva (Spanish), Koroha (Japanese), Hulba (Arabian), Bockshorklee (German), Halba (Malaya) and

Ku-Tou (China).

Fenugreek has an extended history in ayurvedic and Chinese medicine for medicinal purpose and used

for several indications such as labour induction, assisting digestion and as a general stimulant to improve health

and metabolism. It is one of the most ancient medicinal herbs. It has been used as such for centuries as a purpose

of galactogogue. In women, fenugreek is mostly used to increase milk supply (Swafford and Berens, 2000). It

provides natural food fibre and other nutrients required in the human and animal body. Fenugreek supports the

production of milk because it is a rich source of essential fatty acids (Mowrey, 1986). Most applicable part of

234

Patel et al. 2016/J. Livestock Sci. 7: 231-237

Fig. 5: Fenugreek plant (T. foenum-graecum)

(Source: http://www.britannica.com/plant/fenugreek)

Fig. 6: Fenugreek seed (T. foenum-graecum)

Fenugreek (as spice and medicinal purpose) is the seed (Sharma, 1986). Its leaves and seeds have been used

widely to prepare extracts and powders for medicinal uses (Basch et al., 2003). The leaves and seeds have antidiabetic, anti-cancer, anti-microbial, anti-parasitic and procholesterolaemic effects (Al-Habori and Raman,

2002). It is also a tremendous source of selenium, an anti-radiant which helps the body for utilization of oxygen.

They are rich in vitamins such as thiamine, folic acid, riboflavin, niacin, vitamins A, B 6, K and C, and are a rich

source of many minerals such as copper, potassium, calcium, iron, selenium, zinc, manganese, and magnesium.

Fenugreek has been used traditionally by mothers to increase the production of breast milk and quicken milk

flow while nursing and breastfeeding (Toshiyuki et al., 2000). Also, this herb has been shown to significant

effect on the lactation performance in ruminants (Alamer and Basiouni 2005). The biological and

pharmacological actions of fenugreek are associated with the variety of its constituents namely steroids, Ncompounds, polyphenolic substances volatile constituents, amino acids, etc (Mehrafarin et al., 2010).

Supplementation of dairy ration, with fenugreek seeds improves the composition of cow milk (Shah and Mir,

2004). Sayed et al. (2005) mentioned that the fenugreek seed contains phytoestrogens, which are plant

chemicals similar to the female sex hormone estrogen, a key compound, diosgenin, has been shown

experimentally to upsurge milk flow.

Fenugreek seed contains 45 to 60 per cent carbohydrates mainly mucilaginous fibre (galactomannans),

20-30 per cent proteins high in lysine and tryptophan, 5 to 10 per cent fixed oils (lipids), calcium, iron, saponins

(0.6-1.7%), cholesterol, sitosterol, vitamins A, B1, C and nicotinic acid (Mehrafarin et al., 2010). Sinha et al.

(2015) reported that the T. foenum-graecum seed is excellent source of protein (20-30%) high in tryptophan and

lysine; free amino acids i.e. 4-hydroxyisoleucine, arginine, lysine and histidine (25.80%), fat (6.53%), ash

content (3.26%), crude fibre (6.28%), energy (394.46 Kcal/100g seed) and moisture (11.76 %).

Supplementation of fenugreek seeds powder @ 6 0 g per d ay in go ats for seven weeks significantly

increased milk production by 13 per cent ( Alamer and Basiouni, 2005). Adding of fenugreek seed at different

dose rate 2.5 and 5 g/kg body weight for 7 weeks in ewes significantly increase milk yield and body weight gain

(Hassan et al., 2012). Feeding of fenugreek seeds at different levels 5, 10 and 15 per cent of basal diets

significantly increased feed intake and milk yield. When fenugreek seed supplement was increased, it is

concomitant decrease in milk fat percentage and inconsistent pattern in protein, lactose and SNF (Elmnan et

al., 2013). Supplementation of polyherbal combination which contains fenugreek in lactating dairy goats after

2 weeks of kidding for a period of 12 weeks significantly improve milk yield (Galbat et al., 2014). Feeding of

fenugreek seed to basal ration at level 0.6 and 1.2 g/kg body weight in lactating ewes significantly increased

daily feed intake, daily milk yield, milk protein and solid non-fat percentage while the percentage of fat and

lactose were significantly decreased (Al-Sherwany, 2015).

It is concluded that Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus), Jivanti (Leptadenia reticulata) and Methi

(Trigonella foenum-graecum) are effective herbal galactogogue and its uses as feed additive in dairy animals

improve livestock performance in general and milk production in particular. Now a days increasing the demand

of organic food and cost effectiveness in the livestock feed, the use of herbal feed additives has become the

requirement of recent modalities. Utilization of herbal remedies will not only improve the productive efficiency

but improve reproductive efficiency, general health and milk production.

235

Patel et al. 2016/J. Livestock Sci. 7: 231-237

References

1) Agrawal, R.S., Shirale, D.O., Syed, H.M. and Syed, A.A.R. (2015). Physico-chemical properties of fenugreek

(Trigonella foenum-graceum L.) seeds. International Journal of Latest Technology in Engineering,

Management and Applied Science. 4(10): 68-70.

2) Alamer, M.A. and Basiouni, G.F. (2005). Feeding effects of fenugreek seeds (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.)

on lactation performance, some plasma constituents and growth hormone level in goats. Pakistan

Journal of Biological Sciences. 8(11): 1553-1556.

3) Al-Habori, M. and Roman, A. (2002). Pharmacological properties in fenugreek- The genus Trigonella. 1st

Edn. G.A. Petropoulos (Ed.), Taylor and Francis, London and New York, p. 163-182.

4) Al-Sherwany. D.A.O. (2015). Feeding effects of fenugreek seeds on intake, milk yield, chemical composition

of milk and some biochemical parameters in Hamdaniewes. Al-Anbar Journal of Veterinary Sciences.

8(1): 49-54.

5) DADF (2015). Milk Production. In: Annual Report 2014-15. Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and

Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, Govt. of India, New Delhi, p. 4-5.

6) Bakshi, M.P.S. and Wadhwa, M. (2000). Feed additives that modify animal performance. In: Rumen

Microbinl Ecosystem and its Manipulation Techniques (Eds. D.N. Kamra, L.C. Choudhary and N.

Aggarwal), Indian Veterinary Research Institute, lzatnagar, India, p. 125-134.

7) Bakshi, M.P.S., Rani, N., Wadhwa, M. and Kaushal, S. (2004). Impact of herbal feed additives on the

degradability of feed stuffs in vitro. Indian Journal of Animal Nutrition. 21(4): 249-253.

8) Basch, E.C., Ulbricht, G., Kuo, P., Szapary and Smith M. (2003). Therapeutic applications of fenugreek.

Alternative Medicine Review. 8: 20-27.

9) Berhane, M. and Singh, V.P. (2000). Effect of feeding indigenous galactopoietic feed supplements on milk

production in crossbred buffalos. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences. 72(7): 609-611.

10) Chopra, D. and Simon, D. (2000). The Chopra Center.Herbal Handbook. Three Rivers Press, New York,

219: 73-75.

11) Choudhary, B.K. and Kar, A. (1992). Mineral contents of Asparagus racemosus. Indian Drugs. 29: 623.

12) Dadarkar S.S., Deore M.D., Gatne, M.M. (2005). Preliminary evaluation of a polyherbal formulation for its

galactogogue properties in primiparousWistar rats. Journal of Bombay Veterinary College. 13(2): 5053.

13) Elmnan, B.A., Jame, N.M., Rahmatalla, S.A., Amasiab, E.O. and Mahala, A.G. (2013). Effect of

fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) seeds supplementaion on feed intake, some

metabolic hormones profile, milk yield and composition of Nubian goats. Research Journal

of Animal Sciences. 7(1): 1-5.

14) Gabay, M.P. (2002). Galactogogues: Medications that induce lactation. Journal of Human Lactation. 18(3):

274.

15) Galbat S.A., El-Shemy A., Madpoli A.M., Omayma M.A.L., Maghraby, E.I. and El-Mossalam. (2014).

Effects of some medicinal plants mixture on milk performance and blood components of Egyptian

dairy goats. Middle East Journal of Applied Sciences. 4(4): 942-948.

16) Hassan, S.A.A., Shaddad, S.A.I., Salih, K., Muddathir, A., Kheder, S.I. and Barsham, M.A. (2012). Effects

of oral administration of (Fenugreek seeds) on galactagogue, body weight and hormonal Trigonella

foenum-graecum L. levels in Sudanese desert sheep. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical

Sciences. 22(22): 1-5.

17) Hewageegana, S.P., Arawwawala, M., Dhammaratana, I., Ariyawansa, H. and Tisser, A. (2014). Proximate

analysis and standardization of leaves: Leptadenia reticulata (Retz) wight and Arn (Jeevanti). World

Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 3(10): 1603-1612.

18) Jain, M. and Bais, B. (2016).Effect of Jiwanti (Leptadenia reticulata) supplementation on fat percentage and

fat yield of milk produced by Kankrej cows in arid zone of Rajasthan, India. Research and Reviews:

Journal of Veterinary Sciences. 2(1): 1-3.

19) Kirtikar, K.R. and Basu, B.D. (1993). Indian Medicinal Plants, Vol. 2. International Book Publisher,

Dehradun, p. 898-900.

20) Krishna, L., Swarup, D. and Patra, R.C. (2005). An overview of prospects of ethano-veterinary medicine in

India. Indian Journal of Animal Science. 75(12): 1481-1491.

21) Krishna, P.V., Rao, E.V. and Rao, D.V. (1975). Crystalline principles from the leaves and twigs

of Leptadenia reticulata. Planta Medica. 27: 395-400.

22) Kumar, S., Mehla, R.K. and Dang, A.K. (2008). Use of Shatavari(Asparagus racemosus) as a

galactopoietics and therapeutic herb- a review. Agricultural Review. 29(2): 132-138.

23) Mehrafarin, A., Qaderi, A., Rezazadeh, S., NaghdiBadi, H., Noormohammadi, G. and Zand, E. (2010).

Bioengineering of important secondary metabolites and metabolic pathways in fenugreek (Trigonella

foenum-graecum L.). Journal of Medicinal Plants. 9(35): 1-18.

236

Patel et al. 2016/J. Livestock Sci. 7: 231-237

24) Mishra, A., Niranjan, A., Tiwari, S. K., Prakash, D. and Pushpangadan, S. (2005). Nutraceutical

composition of Asparagus racemosus (Shatavari) grown on partially reclaimedsodic soil. Journal of

Medical Aroma and Plant Science. 27(3): 240-248.

25) Moulvi, M.V. (1963). Lactogenic properties of Leptaden. Indian Veterinary Journal. 40: 657.

26) Mowrey, D.B. (1986). The scientific validation of herbal medicine. New camaan, Keats, p. 276-293.

27) Patel, R.P. and Danwala, A.S. (1958). Antimicrobial activity of Leptadenia reticulata. Indian Journal of

Pharmacology. 20: 241-244.

28) Ramesh, P.T., Mitra, S.K., Suryanarayna, T. and Sachan, A. (2000). Evaluation of Galactin, a herbal

galactagogue preparation in dairy cows. Veterinarian. 2(4): 1-3.

29) Ravikumar, B.R. and Bhagwat, V.G. (2008). Study of the influence of Galactin Vet Bolus on milk yield in

lactating dairy cows. Livestock Line. p. 5-7.

30) Ravishankar, B. and Shukla. (2007). Indian systems of medicine: a brief profile. African Journal of

Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines. 4(3): 319-337.

31) Sayed, M.A.M., Azoz, A.A., El-Maqs, A.A. and Adel-Khalek, A.M. (2005). Some performance aspects of

Doe rabbits fed diets supplemented with fenugreek and aniseed. Egyptian Journal of Rabbit Science.

7(3): 147-153.

32) Shah, M.A. and Mir, P.S. (2004). Effect of dietary fenugreek seed on dairy cow performance and milk

characteristics. Canadian Journal of Animal Science. 84: 725-729.

33) Sharma, A. (2010). Influence of polyherbalimunomodulator supplementation on production performance

and milk quality of Karanfries cows. Ph.D. Thesis, National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, Haryana,

India.

34) Sharma, R.D. (1986). Effect of fenugreek seed and leaveson blood glucose and serum insulin responses in

35) human subject. Nutrtional Research. 6: 1353-1364.

35) Singh, S.P., Mehla, R.K. and Singh, M. (2012). Plasma hormones, metabolites, milk production,and

cholesterol levels in Murrah buffaloes fed with Asparagus racemosus in transition and postpartum

period. Tropical Animal Health Production. 44: 1827-1832.

36) Sinha, R., Rauniar, G.P., Panday, D.R. and Adhikari, S. (2015). Fenugreek: pharmacological actions. World

Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 5(1): 1481-1489.

37) Somkuwar, A.P.,Khadtare, C.M., Pawar, S.D. and Gatne, M.M. (2005). Influence of Shatavari feeding on

milk production in buffaloes. Pashudhan. 31(2): 3.

38) Sonara, G.B.,Saralaya, M.G. and Gheewala, N.K. (2013). A Review on Phytochemical and

Pharmacological Properties of Leptadenia reticulata (Retz) Wight and Arn. Pharma Science Monitor:

An International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 4(1): 3408-3417.

39) Sridhar, N.B. and Bhagwat, V.G. (2007). Study to assess the efficacy and safety of Galactin Vet bolus in

lactating dairy cows. Mysore Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 41(4): 496-502.

40) Srivastav, S., Deepak, D. and Khare, A. (1994). Three novel pregnane glycosides from Leptadenia reticulate

wight and Arn. Tetrahedron. 50: 789-798.

41) Sukanya, T.S., Rudraswamy, M.S. and Bharathkumar, T.P. (2014). Performance of Shatavari based herbal

galactogogue- Milkplus supplementation to crossbred cattle of Malnad region. International Journal of

Science and Nature. 5(2): 362-363.

42) Swafford, S. and Berens, B. (2000). Effect of fenugreek on breast milk production. Annual meeting

abstracts. ABM News and Views, 6(3): 10-12

43) Tanwar, P.S., Rathore, S.S. and Kumar, Y. (2008). Effect of Shatavari (Asparagus recemosus) on milk

production in dairy animals. Indian Journal of Animal Research. 42(3): 232-233.

44) Toshiyuki, M., Akinobu, K., Hisashi, M. and Masayuki, Y. (2000). Medicinal Foodstuffs. XVII. 1)

Fenugreek seeds. 3) structures of New furostanol- Type Steroid Saponins, Trigoneosides Xa, Xb, XIb,

XIIa, XIIb and XIIIa from the Seeds of Egyptian Trigonella foenum-graecum L. Chemical and

Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 48(7): 994-1000.

45) Uegaki, R., Ando, S., Ishida, M., Takada, D., Shinokura, K. and Kohchi, Y. (2001). Antioxident activity of

milk from cows fed herbs. Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi. 75(6): 669-671.

46) Visavadiya, N.P. and Narasimhacharya (2005). Hypolipidimic and antioxidant activities of Asparagus

racemosus in hypercholestremic rats. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 37: 376-380.

237

Você também pode gostar

- Perspective of dietetic and antioxidant medicinal plantsNo EverandPerspective of dietetic and antioxidant medicinal plantsAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Polyherbal Galactogogue Supplementation On Milk Yield and Quality As Well As General Health of Surti Buffaloes of South Gujarat PDFDocumento5 páginasEffect of Polyherbal Galactogogue Supplementation On Milk Yield and Quality As Well As General Health of Surti Buffaloes of South Gujarat PDFSureshCoolAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Spirulina (Spirulina Platensis) On Growth Performance and Haemato-Biochemical Parameters of Osmanabadi KidsDocumento4 páginasEffect of Spirulina (Spirulina Platensis) On Growth Performance and Haemato-Biochemical Parameters of Osmanabadi KidsGAJANAN JADHAVAinda não há avaliações

- PSJ Volume 6 Issue 1 Pages 89-97Documento9 páginasPSJ Volume 6 Issue 1 Pages 89-97Aisyah NurAinda não há avaliações

- 2599 6187 1 PBDocumento14 páginas2599 6187 1 PBSiti Nur HalimahAinda não há avaliações

- 9873-Article Text-34035-1-10-20160415Documento6 páginas9873-Article Text-34035-1-10-20160415BAGAS PUTRA PRATAMAAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Supplement Feeding of ShatavarDocumento4 páginasEffect of Supplement Feeding of ShatavarVarsha RaniAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper On Pharmacognosy Study of Flaxseed To Treat HypertensionDocumento6 páginasResearch Paper On Pharmacognosy Study of Flaxseed To Treat HypertensionSHWETA GOKHALEAinda não há avaliações

- The Effect of Herbs On Milk Yield and Milk QualityDocumento7 páginasThe Effect of Herbs On Milk Yield and Milk QualityAbery AuAinda não há avaliações

- Condiciones de CultivoDocumento12 páginasCondiciones de CultivoRomano Abel Miranda GaytanAinda não há avaliações

- Use of Ethno-Veterinary Medicine For Therapy of Reprod DisordersDocumento11 páginasUse of Ethno-Veterinary Medicine For Therapy of Reprod DisordersgnpobsAinda não há avaliações

- Gavar's ProjectDocumento66 páginasGavar's ProjecttsrforfunAinda não há avaliações

- Moringa คุณอัญชลีกรDocumento5 páginasMoringa คุณอัญชลีกรSujith KuttanAinda não há avaliações

- Development and Physico Chemical Analysis of Fortified Vegan Probiotic Fruit Yogurt With Ashwagandha Withania SomniferaDocumento6 páginasDevelopment and Physico Chemical Analysis of Fortified Vegan Probiotic Fruit Yogurt With Ashwagandha Withania SomniferaResearch ParkAinda não há avaliações

- Panchagavya: A Low Cost Organic Input in Organic Farming-A ReviewDocumento3 páginasPanchagavya: A Low Cost Organic Input in Organic Farming-A ReviewHugo MoraAinda não há avaliações

- Potential Application of Milk and Milk Products As Carrier For Herbs and NutraceuticalsDocumento18 páginasPotential Application of Milk and Milk Products As Carrier For Herbs and NutraceuticalsSubhan Aristiadi RachmanAinda não há avaliações

- Ven CobbDocumento12 páginasVen CobbKasmi AgronomieAinda não há avaliações

- Mahua: A Boon For Pharmacy and Food IndustryDocumento11 páginasMahua: A Boon For Pharmacy and Food IndustryIboyaima singhAinda não há avaliações

- Flaxseeds PDFDocumento16 páginasFlaxseeds PDFDanaAinda não há avaliações

- 1575-Article Text-4100-1-10-20191202Documento7 páginas1575-Article Text-4100-1-10-20191202Mathilda PasaribuAinda não há avaliações

- JWorldPoultRes84105 1102018 PDFDocumento6 páginasJWorldPoultRes84105 1102018 PDFIlham ArdiansahAinda não há avaliações

- 15 NavoditaDocumento5 páginas15 NavoditaPradipta ShivaAinda não há avaliações

- Supplementary Effect of K. Alvarezii Baesd Seaweed Product On Milk Production, Its Composition and Organoleptic Appraisal in Crossbred CowsDocumento6 páginasSupplementary Effect of K. Alvarezii Baesd Seaweed Product On Milk Production, Its Composition and Organoleptic Appraisal in Crossbred Cowsupright.hubAinda não há avaliações

- Performance Assessment of Broiler Poultry Birds Fed On Herbal and Synthetic Amino AcidsDocumento3 páginasPerformance Assessment of Broiler Poultry Birds Fed On Herbal and Synthetic Amino AcidsDharmendra B MistryAinda não há avaliações

- Art Current Use of Phytogenic Feed Additives PDFDocumento10 páginasArt Current Use of Phytogenic Feed Additives PDFIonela HoteaAinda não há avaliações

- AN23268Documento13 páginasAN23268xjascoxAinda não há avaliações

- Cowpathy and Vedic Krishi To Empower Food and Nutritional Security and Improve Soil Health: A ReviewDocumento16 páginasCowpathy and Vedic Krishi To Empower Food and Nutritional Security and Improve Soil Health: A ReviewHemrajKoiralaAinda não há avaliações

- Antidiarrheal and Antiulcer Activity of Amaranthus Spinosus in Experimental AnimalsDocumento9 páginasAntidiarrheal and Antiulcer Activity of Amaranthus Spinosus in Experimental AnimalskhnumdumandfullofcumAinda não há avaliações

- 2016.harbal BiscuitDocumento5 páginas2016.harbal BiscuitShamoli AkterAinda não há avaliações

- A Review On Importance of Panchagavya in Vrikshayurveda (PDFDrive)Documento19 páginasA Review On Importance of Panchagavya in Vrikshayurveda (PDFDrive)Amol GoreAinda não há avaliações

- Applications of Nutrigenomics in AnimalDocumento4 páginasApplications of Nutrigenomics in AnimalMelani BertolottiAinda não há avaliações

- Medicinal Plants For Chicken FeedDocumento59 páginasMedicinal Plants For Chicken FeedkarikambingAinda não há avaliações

- Shatavari (Asparagus Racemosus) : January 2019Documento25 páginasShatavari (Asparagus Racemosus) : January 2019howesteveAinda não há avaliações

- 2013 Article 959Documento8 páginas2013 Article 959Sipend AnatomiAinda não há avaliações

- Animals 10 02150Documento18 páginasAnimals 10 02150evelAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Cocoyam Colocasia Esculenta Unripe Plantain Musa Paradisiaca or Their Combination On Glycated Hemoglobin Lipogenic Enzymes and LipidDocumento8 páginasEffect of Cocoyam Colocasia Esculenta Unripe Plantain Musa Paradisiaca or Their Combination On Glycated Hemoglobin Lipogenic Enzymes and LipidGoummeli6 SocratesAinda não há avaliações

- Broilers Given Moringa Oelifera Via Drinking WaterDocumento5 páginasBroilers Given Moringa Oelifera Via Drinking WaterEightch Peas100% (1)

- TEMMY'S FINAL PROJECT 2nd JULY, 2023Documento62 páginasTEMMY'S FINAL PROJECT 2nd JULY, 2023Dee-way Computer InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of ShatavariDocumento5 páginasEffect of ShatavariEvi WulandariAinda não há avaliações

- FINAL-NA-THIS-THESIS-DRAFT - Editeeed Esth - 100522Documento24 páginasFINAL-NA-THIS-THESIS-DRAFT - Editeeed Esth - 100522Jake SagadAinda não há avaliações

- Growth Promotiive and Feed Consumption Effect of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa) Powder in Broiler Chickens Raised in SokotoDocumento10 páginasGrowth Promotiive and Feed Consumption Effect of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa) Powder in Broiler Chickens Raised in SokotoCentral Asian StudiesAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Nutrition: Original Research ArticleDocumento7 páginasAnimal Nutrition: Original Research Articleعمار الشافعيAinda não há avaliações

- LWT - Food Science and TechnologyDocumento8 páginasLWT - Food Science and TechnologyPepe Navarrete TudelaAinda não há avaliações

- 2-5-27-425 Pachgavya PDFDocumento4 páginas2-5-27-425 Pachgavya PDFMahesh BawankarAinda não há avaliações

- Super Foods For Liver Health A CriticalDocumento8 páginasSuper Foods For Liver Health A CriticalLili BujorAinda não há avaliações

- Guava-Enriched Dairy Products: A ReviewDocumento5 páginasGuava-Enriched Dairy Products: A ReviewDr-Paras Porwal100% (2)

- 75 1369832969 PDFDocumento6 páginas75 1369832969 PDFNur Hayati IshAinda não há avaliações

- Hematological and Intestinal Responses of BroilersDocumento10 páginasHematological and Intestinal Responses of BroilersSuci EkoAinda não há avaliações

- 007 PatelDocumento9 páginas007 Patelmofy09Ainda não há avaliações

- Potential Role of Important Nutraceuticals in Poultry Performance and Health - A Comprehensive ReviewDocumento21 páginasPotential Role of Important Nutraceuticals in Poultry Performance and Health - A Comprehensive ReviewUmmul MasirAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Ijasrfeb20186Documento6 páginas6 Ijasrfeb20186TJPRC PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- The Effects of Dietary Turnip (Brassica Rapa) and Biofuel Algae On Growth and Chemical Composition in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss) JuvenilesDocumento7 páginasThe Effects of Dietary Turnip (Brassica Rapa) and Biofuel Algae On Growth and Chemical Composition in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss) JuvenilesKatarzinaAinda não há avaliações

- Limacinum On Lactating Dairy Cows in Terms of Animal HealthDocumento15 páginasLimacinum On Lactating Dairy Cows in Terms of Animal HealthAdriano MariniAinda não há avaliações

- 24 Res Paper-23 PDFDocumento11 páginas24 Res Paper-23 PDFZaminur RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Efficacy of A Phytogenic Formulation As A Replacer of Antibiotic Growth Promoters at Improving Growth, Performance, Carcass Traits and Intestinal Morphology in Broiler ChickenDocumento11 páginasEfficacy of A Phytogenic Formulation As A Replacer of Antibiotic Growth Promoters at Improving Growth, Performance, Carcass Traits and Intestinal Morphology in Broiler ChickenSusmita ThullimalliAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Feeding AzollaDocumento5 páginasEffect of Feeding AzollaTarigAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Ethanol Based Moringa Oleifera Extract On The Internal Organ of BroilersDocumento24 páginasEffect of Ethanol Based Moringa Oleifera Extract On The Internal Organ of Broilersubi nkanuAinda não há avaliações

- Galactagogue Effect BananaflowerDocumento7 páginasGalactagogue Effect BananaflowerSamhitha Ayurvedic ChennaiAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Ijapbcraug20171Documento6 páginas1 Ijapbcraug20171TJPRC PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Duhok Polytechnic University: Unit Operation Laboratory of Unit OperationDocumento7 páginasDuhok Polytechnic University: Unit Operation Laboratory of Unit OperationMUHAMMAD AKRAMAinda não há avaliações

- Rectifier Design For Fuel Ethanol PlantsDocumento7 páginasRectifier Design For Fuel Ethanol PlantsenjoygurujiAinda não há avaliações

- Profil Farmakikinetik Pantoprazole InjeksiDocumento17 páginasProfil Farmakikinetik Pantoprazole InjeksitikaAinda não há avaliações

- DSC Products With CodesDocumento6 páginasDSC Products With CodesmelvinkuriAinda não há avaliações

- K02 Mechanical Seal Leak - RCA DocumentDocumento8 páginasK02 Mechanical Seal Leak - RCA DocumentMidha NeerAinda não há avaliações

- Heterogeneous Azeotropic Distillation Column DesignDocumento67 páginasHeterogeneous Azeotropic Distillation Column Designvenkatesh801100% (1)

- 4013 Stability TestingDocumento5 páginas4013 Stability TestingtghonsAinda não há avaliações

- Resins For Decorative Coatings: Product GuideDocumento27 páginasResins For Decorative Coatings: Product GuideMaurice DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Grundfosliterature-836 - (PG 10,24-25)Documento226 páginasGrundfosliterature-836 - (PG 10,24-25)anggun100% (1)

- AAMA 620-02 Voluntary Specfications For High Performance...Documento9 páginasAAMA 620-02 Voluntary Specfications For High Performance...zaheerahmed77Ainda não há avaliações

- Asm Comp TT Stainless SteelDocumento33 páginasAsm Comp TT Stainless SteelmarriolavAinda não há avaliações

- Answer Key Solubility Product Constant Lab HandoutDocumento8 páginasAnswer Key Solubility Product Constant Lab HandoutmaryAinda não há avaliações

- Adrif Vision List New 11.02.2021Documento2 páginasAdrif Vision List New 11.02.2021rahsreeAinda não há avaliações

- Chemical Equilibrium (Reversible Reactions)Documento22 páginasChemical Equilibrium (Reversible Reactions)Anthony AbesadoAinda não há avaliações

- Reverse Osmosis R12-Wall Mount Installation InstructionsDocumento15 páginasReverse Osmosis R12-Wall Mount Installation InstructionsWattsAinda não há avaliações

- 715 1Documento155 páginas715 1Aniculaesi MirceaAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Enzyme ActionDocumento18 páginasFactors Affecting Enzyme Actionanon_458882066Ainda não há avaliações

- Aspen Internet Process Manual2006 - 5-Usr PDFDocumento18 páginasAspen Internet Process Manual2006 - 5-Usr PDFBabak Mirfendereski100% (1)

- Water VapourDocumento11 páginasWater VapourivanmjwAinda não há avaliações

- Phenguard™ 935: Product Data SheetDocumento6 páginasPhenguard™ 935: Product Data SheetMuthuKumarAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Mineral DepositsDocumento9 páginasPhilippine Mineral DepositsLara CharisseAinda não há avaliações

- Optimization The Effect of Decanter Cake With Fermented Fertilizer of Cow Urine in Edamame Growth and YieldDocumento7 páginasOptimization The Effect of Decanter Cake With Fermented Fertilizer of Cow Urine in Edamame Growth and Yieldvasantha vasuAinda não há avaliações

- 20 eDocumento57 páginas20 eakanksha vermaAinda não há avaliações

- STRUCTURE OF ATOMS - DoneDocumento16 páginasSTRUCTURE OF ATOMS - DoneRaghvendra ShrivastavaAinda não há avaliações

- Soyaben ProjectDocumento66 páginasSoyaben ProjectAmeshe Moges100% (1)

- BV 300 Layer Management Guide: Types of HousingDocumento20 páginasBV 300 Layer Management Guide: Types of HousingBINAY KUMAR YADAV100% (1)

- Dequest 2040, 2050 and 2060 Product SeriesDocumento9 páginasDequest 2040, 2050 and 2060 Product SeriesLê CôngAinda não há avaliações

- IncroquatBehenylTMS 50DataSheetDocumento7 páginasIncroquatBehenylTMS 50DataSheetKirk BorromeoAinda não há avaliações

- Excel Meracik Nutrisi Bandung 11 Feb 2018Documento30 páginasExcel Meracik Nutrisi Bandung 11 Feb 2018Ariev WahyuAinda não há avaliações

- Astm D3302-D3302M-12Documento8 páginasAstm D3302-D3302M-12Sendy Arfian SaputraAinda não há avaliações