Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Assessing China's High Speed Rail Development - Revised - 2016

Enviado por

David WolfTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Assessing China's High Speed Rail Development - Revised - 2016

Enviado por

David WolfDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Chinas High Speed Rail

Running head: CHINAS HIGH SPEED RAIL

ASSESSING CHINAS HIGH-SPEED RAIL DEVELOPMENT: A POLICY ANALYSIS

David Wolf

Oxnard, California

Revised September 1, 2016

Chinas High Speed Rail

Abstract

Once cited by President Barack Obama as a model for the future of U.S. intercity transportation,

Chinas high-speed passenger rail (HSR) system came under scathing attack from many quarters

following revelations of corruption and mismanagement at the top of the Ministry of Railways

and within the HSR construction complex. Based on current business literature and personal

observations, this paper concludes that, in view of Chinas particular circumstances, HSR is a

natural and necessary component of Chinas evolving transportation system, and that debate on

HSR in China must focus on the institutions and oversight necessary to guide its success.

Chinas High Speed Rail

Assessing Chinas High-Speed Rail Policies

Growing in prominence among the challenges facing Chinas policy makers is the matter

of how to provide transportation to Chinas increasingly prosperous and mobile population. The

issue has become acute. Reliance on a traditional travel infrastructure personal automobiles,

buses, standard railroads, coastal ferries, and commercial aviation has left China not only

unable to cope not only with extraordinary events (like the Chinese New Year blizzard of 2008),

but with the encumbrances of holiday travel rushes and, in some cases, with ordinary daily

commuting volumes. Making the issue more vexing is that the same infrastructure is tasked with

the logistical burdens of Chinas export economy and the growing material demands of the

nations urban population.

Against this background, China finds itself in uncharted territory. No country in history

has faced the particular set of challenges confronting the nations leadership as it seeks to

construct a scalable and resilient transportation infrastructure. There are no models to follow, no

solutions to copy, and precious little time for experimentation. Decisions on, and commitments

to, wholesale reconstruction of the nations transportation infrastructure are made in an

environment of economic and political urgency that put haste before care.

The choice has been to invest heavily in order to add capacity to all transportation

networks, but a particular focus has been given to the development of an unprecedented network

of intercity high-speed rail (HSR.) China now has over 8,358 kilometers of HSR lines in service

and a like amount under construction, and the central government has allocated over US$106

billion for HSR construction in 2011 alone. (Dyer, 2011) The effort has won the attention of the

world and the praise of U.S. President Barack Obama, and has revitalized support for high-speed

rail projects in the United States. (Allen, 2010)

Chinas High Speed Rail

But discomfiting revelations have begun to surface about the build-out of the HSR

network. The central government had already begun a review of the program when state news

agency Xinhua announced on February 13, 2011 that Minister of Railways Liu Zhijun, who has

spearheaded HSR development during his eight years in office, had been removed from his post

and placed under investigation for what were apparently corruption-related charges. (Dyer, 2011)

Unsurprisingly, this news provoked a flow of criticism of Chinas HSR plans from

overseas. What was perhaps surprising about the tone of the criticism was the focus not on the

specific shortcomings in the construction or management of the system, but of the very idea of

HSR in China. Representative of the programs critics was Tim Ferguson, the New York-based

editor of Forbes Asia magazine. Writing in his column, Ferguson (2011) noted that a large HSR

network was not appropriate to Chinas needs, and that it was merely another symptom of a

bubble economy in which vast sums are misspent on underutilized assets.

Not So White An Elephant

Continuing revelations make clear that there has indeed been waste, likely fraud, and

both perhaps on a massive scale in the construction of Chinas high-speed rail system. The most

recent report, that of some US$30 million of misallocations in the construction of the BeijingShanghai high-speed rail line, appears to be but the first of many similar disclosures to come.

(Anderlini, 2011) And while an analysis of U.S. transportation needs is outside the scope of this

paper, lessons learned in China may well call into question the viability of planned HSR systems

in the United States,1 short of sustained record highs in petroleum prices or a quadrupling of the

U.S. population. What is lost in the heat of what is becoming a highly politicized debate,

The Obama administrations use of Chinas HSR system as an admirable model for the US appears to be the

source of much of the antipathy US critics like Ferguson (2011) and fellow columnist Joel Kotkin (2011) express

toward Chinese HSR.

Chinas High Speed Rail

however, is that neither of these factors militate against the viability of and the long-term need

for high-speed passenger rail in China.

China has had for some time examples of high-speed intercity rail lines that are arguably

successful and popular, including the Shenzhen Guangzhou, the Beijing Tianjin, and the

Shanghai Hangzhou lines.2 Indeed, one could argue that it was the very success of these

projects that provided proof-points for the significant expansion of China's own bullet trains.

These projects form a small but essential part of the nations intercity transportation

infrastructure, and thus appear to have laid to rest the question of whether HSR is appropriate

for China.

What remains to be assessed is whether or not a wider adoption of HSR in China is

necessary or appropriate, or whether it is, as Ferguson suggests, misspending on assets destined

to be underutilized. First, it is essential to note that the lines mentioned above are limited

examples of routes with extraordinary situations. The distances between the city pairs are too

great or too traffic-laden for taxi, bus, or personal automobile, and are too near to justify air

travel. There is also already a great deal of traffic between the two cities, with one sometimes

serving as a satellite to the other. Other city pairs like this would include ChongqingChengdu,

ShanghaiNanjing, WuhanChangsha, JinanQingdao, and ShenyangDalian. There is an

argument to be made that China should have limited its high-speed intercity rail to just such city

pairs, and if China were a developed country whose populace had already completed its

migration from the countryside to the cities, this argument would be worth making.

Despite growing popularity with riders, there are considerable challenges in determining whether these lines can

yet be termed financial successes. Financial results from the Guangzhou Shenzhen line are mixed with revenues

from through trains and freight trains. The Beijing Tianjin line is still losing money after three years, but is

approaching breakeven and may well become profitable within a year, and the Shanghai Hangzhou line has just

upgraded its track and rolling stock to accommodate even faster trains and has not released financial results.

Chinas High Speed Rail

Driving High Speed Rail

China is, however, not yet a developed country, and we have not yet seen the nation pass

the halfway mark on the urbanization of its population. It is, however, growing and urbanizing

rapidly, and those changes compel the nation's leaders to project two decades or more into the

future when making transportation infrastructure investment decisions. As the nations leaders

contemplate their options, they face a series of factors that argue in favor of wider rollout of

high-speed passenger rail:

Urbanization - Chinas population is leaving the countryside and becoming increasingly

urban. As Richard Hobbs noted in a recent article in Foreign Policy, by 2030 China will have 44

cities boasting populations in excess of 4 million souls, and 221 cities with over 1 million in

population. To put that into perspective, in 2009 the United States had two cities in excess of 4

million souls, New York and Los Angeles, and only 10 with a population over 1 million. In

essence, within two decades, China will have 44 cities equal to or larger than Los Angeles in

population. (Dobbs, 2010) This suggests that the number of viable city pairs for HSR will grow

accordingly.

Density - Chinas urban population density is high, and it is growing, in particular along

nations seaboard. Even as of 2006, China's urban population density - the average number of

people living in a square mile of a city - was 27,300, three times the global average and nine

times the U.S. average, even excluding Macao and Hong Kong in China's figures.

Megacities - China is planning the creation of at least two and possibly more mega-cities,

one clustered around Guangzhou in the Pearl River Delta, and one around Beijing and the North

China plain. These cities will be so large as to require a re-thinking of intracity transportation.

Chinas High Speed Rail

High-speed passenger rail is likely to form the core of the mega-city rapid transit system, linking

thence to subways, taxis, and bus lines.

Energy - Built around gasoline-powered automobiles, diesel-powered buses, and

kerosene-powered aircraft, Chinas transportation network is dependent on supplies of imported

petroleum, and that dependence is growing as China grows. Policy-makers seeking viable

transportation options that are not beholden to the petroleum supply are naturally drawn to rail,

and would thus likely to favor HSR as a substitute for air travel on shorter routes.

Environment - China's leaders breathe the same air the rest of us do, and it would take a

theatrical degree of paranoia to think that they delight in modern cities with sludge-enshrouded

skylines. High-speed rail, if fueled by dirty-coal generated electricity, is not going to make

China's air any cleaner, but the ability to drive it based on nuclear, wind, solar, wave and other

forms of cleanly-generated electricity make it a potentially greener means of intercity travel than

buses and aircraft.

Expertise - The other development motive behind high-speed rail is the belief that if

China can build tens of thousands of kilometers of high-speed railways, along with the

equipment, locomotives, rolling stock, and software to make it all run, the nation can become a

global player in the construction and management of such railroads. The effort is already

underway, most notably in California's on-again, off-again high speed rail project, where CSR is

partnering with GE on one bid for the trains themselves, China Rail Construction Corporation is

partnering with Fresno County to bid on a maintenance and repair facility, and China itself has

dropped hints about financing the whole venture.

Chinas High Speed Rail

Policy Recommendations: Begin with Economics

Politics and face aside, then, there is a strong if not compelling case for HSR in China.

The danger, however, is in being so convinced by that case that HSR becomes a panacea for

most or all of Chinas transportation needs. China is not the United States, where modest

population densities, distances, and terrain make HSR a challenge, but nor is it Western Europe

or Japan, where smaller geographies and population distributions are challenging for air travel in

an age of expensive petroleum.

What critics should be focused on, therefore, are factors that threaten the success and

viability of the system, and on inciting a process designed to lead to an intelligent, well-planned

rollout of an appropriate HSR system. An injection of systemic sobriety to counter the early

intoxication with HSR is in order, and that calls for tools and institutions to evaluate projects

with at least a modest degree of objectivity and transparency.

Because of the fixed, inflexible nature of high-speed rail's assets (as opposed to, say,

those of an airline, which can be shifted with relative ease) an essential first step would be the

creation of a clear process and an economic framework within which the National Development

and Reform Commission (NDRC) can evaluate the current and projected viability of a given line

over the long term. Clearly the success of the early lines suggest the beginnings of such a

template: Beijing to Shenyang, yes, Beijing to Urumqi, probably not.

Where the model would serve the greatest value is in the cases of those routes that fall

somewhere between the two extremes. To take a prominent example, despite the attractiveness

of the BeijingShanghai HSR to executives, professionals, commuters, tourists and senior

cadres, the route between the two cities probably stretches the distance limit of a viable HSR

line. Much longer than this, or even with a line of a shorter length and less attractive city pairs,

Chinas High Speed Rail

and a simple time-in-motion study is likely to reveal that air travel is the better option. (Indeed, it

may well be this factor that inhibits ridership on the WuhanGuangzhou HSR line.)

Policy Recommendations: Institutions and Infrastructure

Time in motion studies, engineering studies, and economic evaluations would all be

worthwhile, but only if conducted by institutions and individuals lacking a vested interest in a

given decision. The NDRC is named above as the evaluating agency for HSR lines. This is not

an arbitrary assignation. A brief digression is in order so as to explain.

Among other phenomena, Chinas development has seen the emergence of what can be

called government-industrial complexes, which we will abbreviate here GICs. Often as the

result of national industrial policy, a regulatory agency will be appointed by the central

government to aid and encourage the development of a domestic industry. In the cases of several

sectors, in particular those concerned with the development of infrastructure (but extending into

such areas as banking and entertainment), that assistance often includes projects or plans over

which the regulatory agency holds budgetary discretion. Over time, the relationship between the

regulator and the companies it regulates (especially the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in its

sector) grows closer. Even if the agency is not effectively captured by the industry and in the

absence of outright corruption, a commonality of interests emerges that can inhibit the

determination with which an agency pursues its regulatory mandate. (see Hanson and Yosifson,

2003; Davidoff, 2010.)

The implicit message behind the sacking of the railways minister is that a RailwayIndustrial Complex appears to have developed in China between and among the ministry, the rail

construction companies, and the domestic enterprises that manufacture the materials and

Chinas High Speed Rail

10

equipment used in railway construction. For our purposes, this means that in order to maintain

some degree of objectivity and transparency, the final evaluation of the viability of HSR lines in

the future will require an agency from well outside this triangle, and preferably senior to the

ministry itself. Given the vast sums at stake and the unraveling issues at the top of the Railways

ministry, it should not come as a surprise if controls of precisely this nature were not already

under active discussion.

Afterword: The Communist Canard

It is tempting to lay Chinas HSR problems at the foot of the nations system of

government, and Ferguson succumbs. He suggests that the real problem with HSR in China is

that the market mechanism is missing, and that all of this money spent on high-speed rail is a

massive misallocation of resources that is a hallmark of top-down systems such as in

Communist China.

It is outside of the scope of this paper to offer even a cursory catalogue of the massive

misallocations of resources that have taken place in presumably bottom-up polities like the

United States, Britain, Japan, and the nations of the European Union. It should be sufficient to

say that the historical record gives ample proof that "top-down systems" like those in China

enjoy no monopoly over expensive government boondoggles, and that the problem of regulatory

emerged in free-market economies (see Hanson and Yosifson, 2003; Davidoff, 2010.)

Further, it is worth pointing out that one of the few downsides of market mechanisms is

that they occasionally stand in the way of solutions that make more sense when the full costs of

implementation are considered. I grew up in a Los Angeles choked by its forced dependence on

the automobile, the results of a GIC formed between local government and automotive interests

that dismantled a viable interurban rapid transit system because it didn't want to pay for

Chinas High Speed Rail

upgrades. (Span, 2003) Half a century later, a new generation of southern Californians

confronting the limitations of automotive transport is footing the bill to rebuild it completely.

Given the pressures of its accelerated development, China can ill-afford this kind of market

mechanism.

11

Chinas High Speed Rail

12

References

Allen, Greg (2010, January 28). Obama announces high-speed rail projects. National Public

Radio, January 28, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=123081477

Anderlini, Jamil (2011, March 23). Corruption hits Chinas high-speed railway. Financial Times,

March 23, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/a50fa362-557211e0-a2b1-00144feab49a.html#axzz1HTiEYUXh

Bishop, Bill (2010, December 31). Greater Beijing? Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei may start urban

integration plan. In Sinocism. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.sinocism.com/archives/1428

Davidoff, Stephen M. (2010, June 11). The Governments Elite and Regulatory Capture. In The

New York Times DealBook, June 11, 2010. Retreived March 23, 2011 from

http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2010/06/11/the-governments-elite-and-regulatory-capture/

Dobbs, Richard (2010, September). Megacities: FPs guide to the coming age. Foreign Policy,

September-October 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2010/08/16/prime_numbers_megacities?page=full

Dyer, Geoff (2011, February 13) Chinas railway chief dismissed. Financial Times, February 13,

2011. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/74a2a87a-3734-11e0-b91a00144feabdc0.html#axzz1HTiEYUXh

Ferguson, Joe (2011, March 2). Chinas high-speed rail: highly suspect. Forbes. Retrieved

March 23, 2011 from http://blogs.forbes.com/timferguson/2011/03/02/chinas-high-speed-railhighly-suspect/

Chinas High Speed Rail

13

Hanson, Jon D. and Yosifon, David G. (2003). The Situation: An Introduction to the Situational

Character, Critical Realism, Power Economics, and Deep Capture. University of Pennsylvania

Law Review, Vol. 152, p. 129, 2003-2004; Santa Clara Univ. Legal Studies Research Paper

No. 06-17; Harvard Public Law Working Paper No. 08-32. Available at SSRN:

http://ssrn.com/abstract=938005

Kotkin, Joel (2011, February 18). Obamas high-speed rail obsession. Forbes. Retreived March

23, 2011 from http://blogs.forbes.com/joelkotkin/2011/02/18/obamas-high-speed-railobsession/

Los Reyes inaugurarn el AVE a Valencia, y los Prncipes la conexin a Albacete (2010,

December 10) Europapress. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.europapress.es/economia/transportes-00343/noticia-economia-ave-reyesinauguraran-ave-valencia-principes-conexion-albacete-20101210123611.html

Span, Guy (2003) Paving the way for buses the great GM streetcar conspiracy, part II the plot

clots. In BayCrossings.com. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.baycrossings.com/Archives/2003/04_May/paving_the_way_for_buses_the_great_

gm_streetcar_conspiracy.htm.

Top U.S. cities by population and rank (n.d.). In Infoplease. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0763098.html

World urban population density by country and area (n.d.) In Demographia. Retrieved March 23,

2011 from http://www.demographia.com/db-intlua-area2000.htm

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- NRL2TRK001 Mod 19 Issue 6 Track Inspection Handbook PDFDocumento47 páginasNRL2TRK001 Mod 19 Issue 6 Track Inspection Handbook PDFChris Avo100% (1)

- Arun Final ProjectDocumento138 páginasArun Final ProjectInkpen studiousAinda não há avaliações

- Dhaka Metro Rail: Dream Comes TrueDocumento10 páginasDhaka Metro Rail: Dream Comes TrueA.S.M. YousufAinda não há avaliações

- Rerailing Systems: Feel The PowerDocumento36 páginasRerailing Systems: Feel The PowerPéter LaczkóAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Transportation EngineeringDocumento50 páginasIntroduction To Transportation EngineeringMakarand KolekarAinda não há avaliações

- AppendicesDocumento63 páginasAppendicesIrina AtudoreiAinda não há avaliações

- Kiwirail Turnaround PlanDocumento2 páginasKiwirail Turnaround PlanTakudzwa S MupfurutsaAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding RoadDocumento96 páginasUnderstanding Roadmarinum7Ainda não há avaliações

- Physical DistributionDocumento17 páginasPhysical DistributionPreethi Selvaraj100% (1)

- Highway & Railway Projects (1) - 25.09.2017-Final AmendedDocumento46 páginasHighway & Railway Projects (1) - 25.09.2017-Final AmendedprashantwathoreAinda não há avaliações

- Celex 32023r1694 enDocumento292 páginasCelex 32023r1694 enTiberivs HadrianvsAinda não há avaliações

- Jharkhand Industrial and Investment Promotion Policy 2016Documento86 páginasJharkhand Industrial and Investment Promotion Policy 2016Ravi BariarAinda não há avaliações

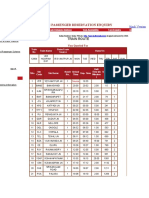

- H Type CouplerDocumento10 páginasH Type CouplerSantosh Sharma50% (2)

- Threshold Radius Formula for Restraining RailDocumento6 páginasThreshold Radius Formula for Restraining RailMohamad SaquibAinda não há avaliações

- Overlaps (Black & Signal)Documento12 páginasOverlaps (Black & Signal)PAUL DURAIAinda não há avaliações

- Agency HouseDocumento29 páginasAgency HouseBipul BhattacharyaAinda não há avaliações

- Field Training ReportDocumento36 páginasField Training ReportashoknrAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Railways Passenger Reservation Enquiry: Train RouteDocumento2 páginasIndian Railways Passenger Reservation Enquiry: Train RouteSatyabrata MohantyAinda não há avaliações

- RDSO Guidelines G-33 Rev.1Documento29 páginasRDSO Guidelines G-33 Rev.1Ashish Goswami86% (7)

- Sergei Glinka Business ManDocumento2 páginasSergei Glinka Business MansergeiAinda não há avaliações

- Coastal ShippingDocumento1 páginaCoastal Shippingpunya.trivedi2003Ainda não há avaliações

- CASNUBDocumento38 páginasCASNUBGajendra Kumar VermaAinda não há avaliações

- JDT WRDocumento1.466 páginasJDT WRKandarp PandyaAinda não há avaliações

- Oakajee Structure Plan ReportDocumento72 páginasOakajee Structure Plan ReportHiddenDAinda não há avaliações

- Improved Switch Expansion Joints Prevent Rail FracturesDocumento44 páginasImproved Switch Expansion Joints Prevent Rail FracturesVatsal VatsaAinda não há avaliações

- Share On Twitter: June 2, 2006Documento4 páginasShare On Twitter: June 2, 2006owais kathAinda não há avaliações

- (Bản HS) GLOBAL SUCCESS 10Documento254 páginas(Bản HS) GLOBAL SUCCESS 10Minh HiếuAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction of Higher Axle Loads On IRDocumento18 páginasIntroduction of Higher Axle Loads On IRAnand KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Report 3 Operations and Maintenance SystemsDocumento141 páginasReport 3 Operations and Maintenance SystemsAjit PatilAinda não há avaliações

- Railways in Colonial Tamil NaduDocumento9 páginasRailways in Colonial Tamil Naduhariharan1Ainda não há avaliações