Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Multimorbidity Clinical Assessment and Management 1837516654789

Enviado por

Stacey WoodsDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Multimorbidity Clinical Assessment and Management 1837516654789

Enviado por

Stacey WoodsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and

management

NICE guideline

Published: 21 September 2016

nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Your responsibility

The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful

consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are

expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and

values of their patients or service users. The application of the recommendations in this guideline

are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare

professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in

consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.

Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied

when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should

do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light

of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance

equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be

interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 2 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Contents

Overview ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4

Who is it for? ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 4

Recommendations .............................................................................................................................................................. 5

1.1 General principles..................................................................................................................................................................... 5

1.2 Taking account of multimorbidity in tailoring the approach to care .................................................................... 6

1.3 How to identify people who may benefit from an approach to care that takes account of

multimorbidity .................................................................................................................................................................................. 6

1.4 How to assess frailty................................................................................................................................................................ 7

1.5 Principles of an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity ........................................................... 8

1.6 Delivering an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity................................................................ 9

1.7 Comprehensive assessment in hospital........................................................................................................................... 13

Terms used in this guideline ......................................................................................................................................................... 13

Putting this guideline into practice ..............................................................................................................................15

Context....................................................................................................................................................................................17

More information............................................................................................................................................................................. 18

Recommendations for research ....................................................................................................................................19

1. Organisation of care................................................................................................................................................................... 19

2. Holistic assessment in the community................................................................................................................................ 20

3. Stopping preventive medicines.............................................................................................................................................. 20

4. Predicting life expectancy........................................................................................................................................................ 22

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 3 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Ov

Overview

erview

This guideline covers optimising care for adults with multimorbidity (multiple long-term conditions)

by reducing treatment burden (polypharmacy and multiple appointments) and unplanned care. It

aims to improve quality of life by promoting shared decisions based on what is important to each

person in terms of treatments, health priorities, lifestyle and goals. The guideline sets out which

people are most likely to benefit from an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity,

how they can be identified and what the care involves.

Who is it for?

Healthcare professionals

People with multimorbidity, their families and carers

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 4 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Recommendations

People have the right to be involved in discussions and make informed decisions about their

care, as described in your care.

Making decisions using NICE guidelines explains how we use words to show the strength (or

certainty) of our recommendations, and has information about prescribing medicines

(including off-label use), professional guidelines, standards and laws (including on consent and

mental capacity), and safeguarding.

1.1

General principles

1.1.1

Be aware that multimorbidity refers to the presence of 2 or more long-term

health conditions, which can include:

defined physical and mental health conditions such as diabetes or schizophrenia

ongoing conditions such as learning disability

symptom complexes such as frailty or chronic pain

sensory impairment such as sight or hearing loss

alcohol and substance misuse.

1.1.2

Be aware that the management of risk factors for future disease can be a major

treatment burden for people with multimorbidity and should be carefully

considered when optimising care.

1.1.3

Be aware that the evidence for recommendations in NICE guidance on single

health conditions is regularly drawn from people without multimorbidity and

taking fewer prescribed regular medicines.

1.1.4

Think carefully about the risks and benefits, for people with multimorbidity, of

individual treatments recommended in guidance for single health conditions.

Discuss this with the patient alongside their preferences for care and treatment.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 5 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

1.2

Taking account of multimorbidity in tailoring the approach to care

1.2.1

Consider an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity if the person

requests it or if any of the following apply:

they find it difficult to manage their treatments or day-to-day activities

they receive care and support from multiple services and need additional services

they have both long-term physical and mental health conditions

they have frailty (see section 1.4) or falls

they frequently seek unplanned or emergency care (see also recommendation 1.3.2)

they are prescribed multiple regular medicines (see section 1.3).

How to identify people who may benefit from an approach to care that

takes account of multimorbidity

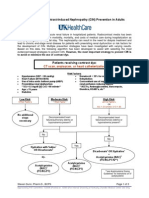

1.3

1.3.1

Identify adults who may benefit from an approach to care that takes account of

multimorbidity (as outlined in section 1.5):

opportunistically during routine care

proactively using electronic health records.

Use the criteria in recommendation 1.2.1 to guide this.

1.3.2

Consider using a validated tool such as eFI, PEONY or QAdmissions, if available

in primary care electronic health records, to identify adults with multimorbidity

who are at risk of adverse events such as unplanned hospital admission or

admission to care homes.

1.3.3

Consider using primary care electronic health records to identify markers of

increased treatment burden such as number of regular medicines a person is

prescribed.

1.3.4

Use an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity for adults of any

age who are prescribed 15 or more regular medicines, because they are likely to

be at higher risk of adverse events and drug interactions.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 6 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

1.3.5

Consider an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity for adults of

any age who:

are prescribed 10 to 14 regular medicines

are prescribed fewer than 10 regular medicines but are at particular risk of adverse

events.

1.4

How to assess frailty

1.4.1

Consider assessing frailty in people with multimorbidity.

1.4.2

Be cautious about assessing frailty in a person who is acutely unwell.

1.4.3

Do not use a physical performance tool to assess frailty in a person who is

acutely unwell.

Primary care and community care settings

1.4.4

When assessing frailty in primary and community care settings, consider using

1 of the following:

an informal assessment of gait speed (for example, time taken to answer the door, time

taken to walk from the waiting room)

self-reported health status (that is, 'how would you rate your health status on a scale

from 0 to 10?', with scores of 6 or less indicating frailty)

a formal assessment of gait speed, with more than 5 seconds to walk 4 metres

indicating frailty

the PRISMA-7 questionnaire, with scores of 3 and above indicating frailty.

Hospital outpatient settings

1.4.5

When assessing frailty in hospital outpatient settings, consider using 1 of the

following:

self-reported health status (that is, 'how would you rate your health status on a scale

from 0 to 10?', with scores of 6 or less indicating frailty)

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 7 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

the 'Timed Up and Go' test, with times of more than 12 seconds indicating frailty

a formal assessment of gait speed, with more than 5 seconds to walk 4 metres

indicating frailty

the PRISMA-7 questionnaire, with scores of 3 and above indicating frailty

self-reported physical activity, with frailty indicated by scores of 56 or less for men and

59 or less for women using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.

1.5

Principles of an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity

1.5.1

When offering an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity, focus

on:

how the person's health conditions and their treatments interact and how this affects

quality of life

the person's individual needs, preferences for treatments, health priorities, lifestyle

and goals

the benefits and risks of following recommendations from guidance on single health

conditions

improving quality of life by reducing treatment burden, adverse events, and unplanned

care

improving coordination of care across services.

1.5.2

Follow these steps when delivering an approach to care that takes account of

multimorbidity:

Discuss the purpose of an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity (see

recommendation 1.6.2).

Establish disease and treatment burden (see recommendations 1.6.3 to 1.6.5).

Establish patient goals, values and priorities (see recommendations 1.6.6 to 1.6.8).

Review medicines and other treatments taking into account evidence of likely benefits

and harms for the individual patient and outcomes important to the person (see

recommendations 1.6.9 to 1.6.16).

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 8 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Agree an individualised management plan with the person (see recommendation

1.6.17), including:

goals and plans for future care (including advance care planning)

who is responsible for coordination of care

how the individualised management plan and the responsibility for coordination

of care is communicated to all professionals and services involved

timing of follow-up and how to access urgent care.

1.6

Delivering an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity

1.6.1

Follow the recommendations in the NICE guideline on patient experience in

adult NHS services, which provides guidance on knowing the patient as an

individual, tailoring healthcare services for each patient, continuity of care and

relationships, and enabling patients to actively participate in their care.

Discussing the purpose of an approach to care that tak

takes

es account of multimorbidity

1.6.2

Discuss with the person the purpose of the approach to care, that is, to improve

quality of life. This might include reducing treatment burden and optimising care

and support by identifying:

ways of maximising benefit from existing treatments

treatments that could be stopped because of limited benefit

treatments and follow-up arrangements with a high burden

medicines with a higher risk of adverse events (for example, falls, gastrointestinal

bleeding, acute kidney injury)

non-pharmacological treatments as possible alternatives to some medicines

alternative arrangements for follow-up to coordinate or optimise the number of

appointments.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 9 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Establishing disease and treatment burden

1.6.3

Establish disease burden by talking to people about how their health problems

affect their day-to-day life. Include a discussion of:

mental health

how disease burden affects their wellbeing

how their health problems interact and how this affects quality of life.

1.6.4

Establish treatment burden by talking to people about how treatments for their

health problems affect their day-to-day life. Include in the discussion:

the number and type of healthcare appointments a person has and where these take

place

the number and type of medicines a person is taking and how often

any harms from medicines

non-pharmacological treatments such as diets, exercise programmes and psychological

treatments

any effects of treatment on their mental health or wellbeing.

1.6.5

Be alert to the possibility of:

depression and anxiety (consider identifying, assessing and managing these conditions

in line with the NICE guideline on common mental health problems)

chronic pain and the need to assess this and the adequacy of pain management.

Establishing patient goals, values and priorities

1.6.6

Clarify with the patient whether and how they would like their partner, family

members and/or carers to be involved in key decisions about the management

of their conditions. Review this regularly. If the patient agrees, share

information with their partner, family members and/or carers. [This

recommendation is adapted from the NICE guideline on patient experience in

adult NHS services.]

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 10 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

1.6.7

Encourage people with multimorbidity to clarify what is important to them,

including their personal goals, values and priorities. These may include:

maintaining their independence

undertaking paid or voluntary work, taking part in social activities and playing an

active part in family life

preventing specific adverse outcomes (for example, stroke)

reducing harms from medicines

reducing treatment burden

lengthening life.

1.6.8

Explore the person's attitudes to their treatments and the potential benefits and

harms of those treatments. Follow the recommendations on patient

involvement in decisions about medicines and understanding the patient's

knowledge, beliefs and concerns about medicines in the NICE guideline on

medicines adherence.

Re

Reviewing

viewing medicines and other treatments

1.6.9

When reviewing medicines and other treatments, use the database of

treatment effects to find information on:

the effectiveness of treatments

the duration of treatment trials

the populations included in treatment trials.

1.6.10

Consider using a screening tool (for example, the STOPP/START tool in older

people) to identify medicine-related safety concerns and medicines the person

might benefit from but is not currently taking. [This recommendation is adapted

from the NICE guideline on medicines optimisation.]

1.6.11

When optimising treatment, think about any medicines or non-pharmacological

treatments that might be started as well as those that might be stopped.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 11 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

1.6.12

Ask the person if treatments intended to relieve symptoms are providing

benefits or causing harms. If the person is unsure of benefit or is experiencing

harms from a treatment:

discuss reducing or stopping the treatment

plan a review to monitor effects of any changes made and decide whether any further

changes to treatments are needed (including restarting a treatment).

1.6.13

Take into account the possibility of lower overall benefit of continuing

treatments that aim to offer prognostic benefit, particularly in people with

limited life expectancy or frailty.

1.6.14

Discuss with people who have multimorbidity and limited life expectancy or

frailty whether they wish to continue treatments recommended in guidance on

single health conditions which may offer them limited overall benefit.

1.6.15

Discuss any changes to treatments that aim to offer prognostic benefit with the

person, taking into account:

their views on the likely benefits and harms from individual treatments

what is important to them in terms of personal goals, values and priorities (see

recommendation 1.6.7).

1.6.16

Tell a person who has been taking bisphosphonate for osteoporosis for at least

3 years that there is no consistent evidence of:

further benefit from continuing bisphosphonate for another 3 years

harms from stopping bisphosphonate after 3 years of treatment.

Discuss stopping bisphosphonate after 3 years and include patient choice, fracture risk

and life expectancy in the discussion.

Agreeing the individualised management plan

1.6.17

After a discussion of disease and treatment burden and the person's, personal

goals, values and priorities, develop and agree an individualised management

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 12 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

plan with the person. Agree what will be recorded and what actions will be

taken. These could include:

starting, stopping or changing medicines and non-pharmacological treatments

prioritising healthcare appointments

anticipating possible changes to health and wellbeing

assigning responsibility for coordination of care and ensuring this is communicated to

other healthcare professionals and services

other areas the person considers important to them

arranging a follow-up and review of decisions made.

Share copies of the management plan in an accessible format with the person and (with

the person's permission) other people involved in care (including healthcare

professionals, a partner, family members and/or carers).

1.7

Comprehensive assessment in hospital

1.7.1

Start a comprehensive assessment of older people with complex needs at the

point of admission and preferably in a specialist unit for older people. [This

recommendation is from the NICE guideline on transition between inpatient

hospital settings and community or care home settings for adults with social

care needs.]

Terms used in this guideline

Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity refers to the presence of 2 or more long-term health conditions, which can include:

defined physical and mental health conditions such as diabetes or schizophrenia

ongoing conditions such as learning disability

symptom complexes such as frailty or chronic pain

sensory impairment such as sight or hearing loss

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 13 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

alcohol and substance misuse.

The management of risk factors for future disease can be a major treatment burden for people with

multimorbidity and should be carefully considered when optimising care.

This guideline covers the optimisation of care for:

adults with 2 or more long-term physical health conditions

adults with 1 or more mental health condition and at least 1 physical health condition.

An approach to care that tak

takes

es account of multimorbidity

An approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity involves personalised assessment and

the development of an individualised management plan. The aim is to improve quality of life by

reducing treatment burden, adverse events, and unplanned or uncoordinated care. The approach

takes account of a person's individual needs, preferences for treatments, health priorities and

lifestyle. It aims to improve coordination of care across services, particularly if this has become

fragmented.

Individualised management plan

An individualised management plan is a management plan covering clinical aspects of a person's

care, such as the medicines they are taking and the services they are attending. It includes

information about which areas of care are most important to the person and whether treatments

have been stopped to reduce treatment burden.

Medicines

Medicines includes topical treatments such as ointments, inhalers, creams and drops, as well as

medicines taken by mouth or injection.

Comprehensiv

Comprehensive

e assessment of older people with comple

complexx needs

A comprehensive geriatric assessment is an interdisciplinary diagnostic process to determine the

medical, psychological and functional capability of someone who is frail and old. The aim is to

develop a coordinated, integrated plan for treatment and long-term support.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 14 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Putting this guideline into pr

practice

actice

NICE has produced tools and resources to help you put this guideline into practice.

Some issues were highlighted that might need specific thought when implementing the

recommendations. These were raised during the development of this guideline. They are:

Using primary care electronic health records to identify people who may benefit from an

approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity may require some area-wide provision

or coordination of search tools if these are not already built into clinical IT systems.

Sharing copies of individualised management plans in an accessible format can be done

electronically such as through the NHS Summary Care Record, with enhanced functionality

now available in 99% of GP practices in England, or by ensuring that the person always has an

up-to-date paper copy of their plan at home.

The most appropriate healthcare professional to develop and implement the individualised

management plan may vary by area and depend on the individual needs and preferences of the

person with multimorbidity. However, it is important that it is clear in different areas who

should generally be responsible.

Putting a guideline fully into practice can take time. How long may vary from guideline to guideline,

and depends on how much change in practice or services is needed. Implementing change is most

effective when aligned with local priorities.

Changes recommended for clinical practice that can be done quickly like changes in prescribing

practice should be shared quickly. This is because healthcare professionals should use guidelines

to guide their work as is required by professional regulating bodies such as the General Medical

and Nursing and Midwifery Councils.

Changes should be implemented as soon as possible, unless there is a good reason for not doing so

(for example, if it would be better value for money if a package of recommendations were all

implemented at once).

Different organisations may need different approaches to implementation, depending on their size

and function. Sometimes individual practitioners may be able to respond to recommendations to

improve their practice more quickly than large organisations.

Here are some pointers to help put NICE guidelines into practice:

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 15 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

1. Raise aawareness

wareness through routine communication channels, such as email or newsletters, regular

meetings, internal staff briefings and other communications with all relevant partner organisations.

Identify things staff can include in their own practice straight away.

2. Identify a lead with an interest in the topic to champion the guideline and motivate others to

support its use and make service changes, and to find out any significant issues locally.

3. Carry out a baseline assessment against the recommendations to find whether there are gaps in

current service provision.

4. Think about what data yyou

ou need to measure impro

improvvement and plan how you will collect it. You

may need to work with other health and social care organisations and specialist groups to compare

current practice with the recommendations. This may also help identify local issues that will slow or

prevent implementation.

5. De

Devvelop an action plan with the steps needed to put the guideline into practice, and make sure it

is ready as soon as possible. Big, complex changes may take longer to implement, but some may be

quick and easy to do. An action plan will help in both cases.

6. For vvery

ery big changes include milestones and the business case, which will set out additional costs,

savings and possible areas for disinvestment. A small project group should develop the action plan.

The group should include the guideline champion, a senior organisational sponsor, staff involved in

the associated services, finance and information professionals.

7. Implement the action plan with oversight from the lead and the project group. Big projects may

also need project management support.

8. Re

Review

view and monitor how well the guideline is being implemented through the project group.

Share progress with those involved in making improvements, as well as relevant boards and local

partners.

NICE provides a comprehensive programme of support and resources to maximise uptake and use

of evidence and guidance. See our into practice pages for more information.

Also see Leng G, Moore V, Abraham S, editors (2014) Achieving high quality care practical

experience from NICE. Chichester: Wiley.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 16 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Conte

Context

xt

Multimorbidity is usually defined as when a person has 2 or more long-term health conditions.

Measuring the prevalence of multimorbidity is not straightforward because it depends on which

conditions are counted. However, all recent studies show that multimorbidity is common, becomes

more common as people age, and is more common in people from less affluent areas. Whereas in

older people multimorbidity is largely due to higher rates of physical health conditions, in younger

people and people from less affluent areas, multimorbidity is often due to a combination of physical

and mental health conditions (notably depression).

Multimorbidity matters because it is associated with reduced quality of life, higher mortality,

polypharmacy and high treatment burden, higher rates of adverse drug events, and much greater

health services use (including unplanned or emergency care). A particular issue for health services

and healthcare professionals is that treatment regimens (including non-pharmacological

treatments) can easily become very burdensome for people with multimorbidity, and care can

become uncoordinated and fragmented. Polypharmacy in people with multimorbidity is often

driven by the introduction of multiple medicines intended to prevent future morbidity and

mortality. However, the case for using these medicines weakens if life expectancy is reduced by

other conditions or frailty. The absolute difference made by each additional medicine may also

reduce when people are taking multiple preventive medicines. The implications of multimorbidity

for organisation of healthcare are highly variable depending on which conditions a person has.

Groups of conditions that have closely related or concordant treatment, such as diabetes,

hypertension and angina, pose fewer problems for coordination than conditions needing quite

different treatment (for example, physical and mental health conditions).

NICE guidelines have been developed for managing many individual diseases and conditions. The

aim of this guideline is to inform patient and clinical decision-making and models of care for people

with multimorbidity who would benefit from a tailored approach because of the high impact of

their conditions or treatment on their quality of life or functioning. This is a particular concern for

generalist medical professionals such as GPs and geriatricians and healthcare professionals such as

pharmacists and nurses working in those services; the guideline is also relevant to specialist

services because many of the patients they care for will have significant other conditions.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 17 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

More information

You can also see this guideline in the NICE pathway on multimorbidity.

To find out what NICE has said on topics related to this guideline, see our web pages on

multiple long-term conditions, older people and medicines management.

See also the guideline committee's discussion and the evidence reviews (in the full guideline),

and information about how the guideline was developed, including details of the committee.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 18 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Recommendations for research

The guideline committee has made the following recommendations for research. The committee's

full set of research recommendations is detailed in the full guideline.

1. Organisation of care

What is the clinical and cost effectiveness of alternative approaches to organising primary care

compared with usual care for people with multimorbidity?

Wh

Whyy this is important

The guideline committee felt that primary care was well suited to managing multimorbidity, but

agreed that this was often challenging partly because of how primary care is currently organised.

However, there was inadequate high-quality research on alternative approaches to organising care

for people with multimorbidity. Trials should be undertaken to examine the impact of different

strategies on important clinical outcomes, quality of life and cost effectiveness. The committee

believed that no single trial could likely address this research need, because there are many

plausible interventions and many defined populations in which such interventions might be of

value.

Large, well-designed trials of alternative ways of organising general practice based primary care for

people with multimorbidity would be of value in defined patient groups (for example, people with

multimorbidity who find it difficult to manage their treatment or care or day-to-day activities,

people with multiple providers or services involved in their care, people with both long-term

physical and mental health problems, people with well-defined frailty, people frequently using

unscheduled care, people prescribed multiple regular medicines, and people who are housebound

or care home residents).

Such trials should have clear identification and justification of the planned target population,

careful piloting and optimisation, and well-described interventions. They need to be sufficiently

powered to provide evidence of clinically important effects of interventions on outcomes that are

relevant to patients and health and social care services (for example, quality of life, hospital and

care home admission, mortality).

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 19 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

2. Holistic assessment in the community

What is the clinical and cost effectiveness of a community holistic assessment and intervention for

people living with high levels of multimorbidity?

Wh

Whyy this is important

There was low quality evidence to indicate potential benefit from community assessments based

on the principles of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older people. However, the studies were

conducted outside the UK and were not aimed at all adults living with multimorbidity. The guideline

committee believed that there was some evidence that holistic assessment and intervention in the

community may be of benefit for older people, but that the evidence was of low quality and not

adequate to inform strong recommendations.

Large, well-designed trials of holistic assessment and intervention in people with multimorbidity

would be of value in defined patient groups in the community (for example, people in nursing

homes, people who are housebound, people of all ages with well-defined frailty, people with high

levels of multimorbidity or polypharmacy).

Such trials must be rigorous, with clear identification and justification of the planned target

population, careful piloting and optimisation, and well-described interventions. They need to be

sufficiently powered to provide evidence of clinically important effects of interventions on

outcomes that are relevant to patients and health and social care services (for example, quality of

life, hospital and care home admission, and mortality).

The guideline committee believed that no single trial could likely address this research need, since

there are many plausible interventions and many defined populations in which such interventions

might be of value. The committee believed that assessment should follow the principles of

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment or the Standardised Assessment of Elderly People in Europe

(STEP) tool, and that interventions would likely involve a multidisciplinary team.

3. Stopping preventive medicines

What is the clinical and cost effectiveness of stopping preventive medicines in people with

multimorbidity who may not benefit from continuing them?

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 20 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

Wh

Whyy this is important

There is good evidence from randomised controlled trials of the medium term (210 years) benefit

of medicines recommended in guidelines for preventing future morbidity or mortality, including

treatments for hypertension, hyperglycaemia and osteoporosis. However, there is much less

evidence about the balance of benefit and harm over longer periods of treatment. It is plausible

that harms outweigh benefits in some people with multimorbidity (for example, because of higher

rates of adverse events in older, frailer people prescribed multiple regular medicines, or because

the expected benefit from continuing a preventive medicine is reduced when there is limited life

expectancy or high risk of death from other morbidities). These people are unlikely to have been

eligible or included in published trials showing initial benefit from preventive medicines. The

systematic review undertaken by NICE in 2015 did not find any randomised controlled trials of

stopping antihypertensive medicines in people with multimorbidity. The review found 1 small

randomised controlled trial of stopping statins in people with a life expectancy of 1 year, but the

committee did not consider this provided enough evidence to make a recommendation. The review

found several randomised controlled trials of stopping bisphosphonates (although not clearly in

populations with multimorbidity) and a recommendation was made for this, but no randomised

controlled trials were found of stopping calcium and/or vitamin D. Recommendations based on

robust evidence on the clinical and cost effectiveness of stopping preventive medicines in people

with multimorbidity who may not benefit could have significant budgetary implications for the

NHS. No ongoing trials have been identified.

The guideline committee considered that 1 or more large, well-designed trials of stopping

preventive medicine in people with multimorbidity would be of value in defined patient groups in

the community (for example, people in nursing homes, people who are housebound, people with

well-defined frailty, people with high levels of multimorbidity or polypharmacy, people with limited

life expectancy). Discontinuation could either be complete (all relevant medicines) or partial (for

example, reduced intensity of hypotensive or hypoglycaemic treatment). Such trials have to be

sufficiently powered to provide evidence of clinically important effects of interventions on

outcomes that are relevant to patients and health and social care systems (for example, quality of

life, hospital and care home admission and mortality). The committee believed that given the

existing evidence, it would be of greater value to evaluate the effects of stopping discrete

medicines or drug classes, rather than stopping all preventive medicines at the same time. The

committee also believed that no single trial could likely address this research need, since there are

many medicines that could be stopped and many defined populations in which this might be of

value.

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 21 of 22

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56)

4. Predicting life expectancy

Is it possible to analyse primary care data to identify characteristics that affect life expectancy and

to develop algorithms and prediction tools for patients and healthcare providers to predict reduced

life expectancy?

Wh

Whyy this is important

Many people take preventive medicines which are likely to offer small benefits because of reduced

life expectancy from other causes. Medicines and other treatments may therefore be adding to

treatment burden without adding quality or length of life. The ability to identify people with

reduced life expectancy could provide healthcare professionals and people with information that

could inform decisions about starting or continuing long-term preventive treatments. Conversely

younger people with multimorbidity and reduced life expectancy may benefit from additional

preventive treatments. Because this information would be used most often in a primary care

setting, the committee considered that a tool derived from information within primary care

databases would be most useful.

ISBN: 978-1-4731-2065-5

Accreditation

NICE 2016. All rights reserved.

Page 22 of 22

Você também pode gostar

- Id 397 TeicoplaninDocumento2 páginasId 397 TeicoplaninStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Switching Ace-Inhibitors: Change To Change From Enalapril Quinapril RamiprilDocumento2 páginasSwitching Ace-Inhibitors: Change To Change From Enalapril Quinapril RamiprilGlory Claudia KarundengAinda não há avaliações

- IDSA Releases Guidance On Antibiotic Selection For Gram-Negative Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacterial Infections - ACP Internist Weekly - ACP InternistDocumento3 páginasIDSA Releases Guidance On Antibiotic Selection For Gram-Negative Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacterial Infections - ACP Internist Weekly - ACP InternistStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Critical CareDocumento8 páginasCritical CareDzikrul Haq KarimullahAinda não há avaliações

- Splenectomy Guideline Final 2012Documento6 páginasSplenectomy Guideline Final 2012Stacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Bacterial and Fungal Infections in Cirrhosis JOH 2021Documento17 páginasManagement of Bacterial and Fungal Infections in Cirrhosis JOH 2021Francisco Javier Gonzalez NomeAinda não há avaliações

- Palliative2 Nausea MedtableDocumento2 páginasPalliative2 Nausea MedtableStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Antithrombotic Therapy For VTE DiseaseDocumento13 páginasAntithrombotic Therapy For VTE DiseaseStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- J Jacadv 2023 100389Documento12 páginasJ Jacadv 2023 100389Edward ElBuenoAinda não há avaliações

- 2023 ESPEN Practical and Partially Revised Guideline - Clinical Nutrition in The Intensive Care UnitDocumento19 páginas2023 ESPEN Practical and Partially Revised Guideline - Clinical Nutrition in The Intensive Care UnitStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Adults at NUH2011 FinalDocumento2 páginasTherapeutic Drug Monitoring in Adults at NUH2011 FinalStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Appropriate Use of Laxatives in The Older PersonDocumento7 páginasAppropriate Use of Laxatives in The Older PersonStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Potasio. 2014.Documento19 páginasPotasio. 2014.Nestor Enrique Aguilar SotoAinda não há avaliações

- Tamiflu PrescribingDocumento26 páginasTamiflu PrescribingStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Antibiotik WhoDocumento49 páginasAntibiotik WhodjebrutAinda não há avaliações

- Contrast NephRopathy GuidelinesDocumento3 páginasContrast NephRopathy GuidelinesStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Information Center/KAUH: Selecting Gluten-Free Antibiotics in Celiac DiseaseDocumento6 páginasDrug Information Center/KAUH: Selecting Gluten-Free Antibiotics in Celiac DiseaseStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Antibiotic Selection - The Clinical AdvisorDocumento6 páginasAntibiotic Selection - The Clinical AdvisorStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- StrokeDocumento2 páginasStrokeStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Procoagulant GuidelineDocumento30 páginasProcoagulant GuidelineStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- C.a.U.S.E. - Cardiac Arrest Ultra-Sound Exam - A Better Approach To Managing Patients in Primary Non-Arrhythmogenic Cardiac ArrestDocumento2 páginasC.a.U.S.E. - Cardiac Arrest Ultra-Sound Exam - A Better Approach To Managing Patients in Primary Non-Arrhythmogenic Cardiac ArrestStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Antimicrobials at The End of LifeDocumento2 páginasAntimicrobials at The End of LifeStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Biomarkers of SepsisDocumento8 páginasBiomarkers of SepsisStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Fluid Choices Impact Outcome in Septic ShockDocumento7 páginasFluid Choices Impact Outcome in Septic ShockStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Stimulant May Speed Antidepressant Response Time in ElderlyDocumento3 páginasStimulant May Speed Antidepressant Response Time in ElderlyStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Elderly Patients Making Wise ChoicesDocumento6 páginasElderly Patients Making Wise ChoicesStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Preoperative Insulin 2013Documento3 páginasPreoperative Insulin 2013Stacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- Airway Clearance in The Intensive Care UnitDocumento5 páginasAirway Clearance in The Intensive Care UnitStacey WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- The ABC of Weaning Failure - A Structured ApproachDocumento9 páginasThe ABC of Weaning Failure - A Structured ApproachArul ShanmugamAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- IDR 69596 Profile of Efinaconazole in The Treatment of Onchomycosis 060115Documento10 páginasIDR 69596 Profile of Efinaconazole in The Treatment of Onchomycosis 060115intankmlsAinda não há avaliações

- ICH Public Meeting Amsterdam 042919Documento125 páginasICH Public Meeting Amsterdam 042919Jose De La Cruz De La O100% (1)

- Non Surgical Fat ReductionDocumento12 páginasNon Surgical Fat ReductionadeAinda não há avaliações

- Kanchana Allan Nursing Resume - New Grad PositionDocumento3 páginasKanchana Allan Nursing Resume - New Grad Positionapi-416448549Ainda não há avaliações

- Fundamentials of Shared Service OperationsDocumento125 páginasFundamentials of Shared Service OperationsОлег Дрошнев100% (3)

- Hiv/aids JournalDocumento9 páginasHiv/aids JournalStar AlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- GSK Case Study & PR PlanDocumento475 páginasGSK Case Study & PR PlanJBull7645100% (1)

- 2010-2011 Annual ReportDocumento130 páginas2010-2011 Annual ReportSlusom WebAinda não há avaliações

- 21cfr11 Checklist (CFR)Documento2 páginas21cfr11 Checklist (CFR)marco_fmAinda não há avaliações

- 108-Epidemiological Studies - A Practical Guide, 2nd Edition-Alan J. Silman Gary J. Macfarlane-05 PDFDocumento256 páginas108-Epidemiological Studies - A Practical Guide, 2nd Edition-Alan J. Silman Gary J. Macfarlane-05 PDFMarisela Fuentes100% (1)

- Acceptability: ©WHO/Sergey VolkovDocumento26 páginasAcceptability: ©WHO/Sergey VolkovBeatriz PatricioAinda não há avaliações

- Adverse Event TemplateDocumento5 páginasAdverse Event TemplateGocThuGianAinda não há avaliações

- Ivermectin For Prophylaxis and Treatment of Covid 19Documento2 páginasIvermectin For Prophylaxis and Treatment of Covid 19jermAinda não há avaliações

- Revised Guidelines on Surveillance and Response to Adverse Events Following ImmunizationDocumento22 páginasRevised Guidelines on Surveillance and Response to Adverse Events Following ImmunizationReanne Pauline Manipon100% (2)

- Reseach (Case Study)Documento25 páginasReseach (Case Study)salahnaser9999Ainda não há avaliações

- MicroCap Review Spring 2019Documento96 páginasMicroCap Review Spring 2019Planet MicroCap Review Magazine67% (3)

- Institute of Lung Health Leicester: Shane CariasDocumento10 páginasInstitute of Lung Health Leicester: Shane CariasShane CariasAinda não há avaliações

- Improving Methods For Estimating Cost of Production in Developing Countries Report JRC Lit Review PDFDocumento19 páginasImproving Methods For Estimating Cost of Production in Developing Countries Report JRC Lit Review PDFHarshithaAinda não há avaliações

- Computers in Biology and MedicineDocumento16 páginasComputers in Biology and MedicineDhanalekshmi YedurkarAinda não há avaliações

- 6 April 2023 Academic Reading Practice TestDocumento14 páginas6 April 2023 Academic Reading Practice TestNguyễn Chính ThạoAinda não há avaliações

- Vaccinepeerreview PDFDocumento1.053 páginasVaccinepeerreview PDFMatthew SharpAinda não há avaliações

- New Drug Application Nda ChecklistDocumento6 páginasNew Drug Application Nda Checklistjzames001Ainda não há avaliações

- Part 1: Introduction Part 2: Responsibilities by Role Part 3: Summary of Key PointsDocumento13 páginasPart 1: Introduction Part 2: Responsibilities by Role Part 3: Summary of Key PointsFaye BaliloAinda não há avaliações

- Submissions & Author Guidelines - American Dental Association - ADADocumento8 páginasSubmissions & Author Guidelines - American Dental Association - ADAjennys420Ainda não há avaliações

- Icoffee Journal 2k22Documento5 páginasIcoffee Journal 2k22Ayur Manthra OrgAinda não há avaliações

- C0EF-1BE9 Dental Medical 4 5825818559418206088 PDFDocumento130 páginasC0EF-1BE9 Dental Medical 4 5825818559418206088 PDFOctavian CiceuAinda não há avaliações

- Pharm NotesDocumento198 páginasPharm NotesNancy Danielz80% (5)

- Boost Community Understanding of Youth LibraryDocumento30 páginasBoost Community Understanding of Youth LibraryErgado A. Aman86% (7)

- Ich-Guideline-S10-Photosafety-Evaluation-Pharmaceuticals-Step-5 - enDocumento17 páginasIch-Guideline-S10-Photosafety-Evaluation-Pharmaceuticals-Step-5 - enHasna Ulya AnnafisAinda não há avaliações

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION CLINICAL TRIALS GUIDANCEDocumento56 páginasEUROPEAN COMMISSION CLINICAL TRIALS GUIDANCEgwapingMDAinda não há avaliações