Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

1 - Comparison Food Served and Consumed

Enviado por

Geraldine Yaskeld FuentesTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

1 - Comparison Food Served and Consumed

Enviado por

Geraldine Yaskeld FuentesDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A comparison of the amount of food served and

consumed according to meal service system

A. Wilson, S. Evans and G. Frost

Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Charing Cross Hospital, Hammersmith Hospitals NHS Trust, Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8RF,

UK

Abstract

Correspondence

Gary Frost,

The Hammersmith Hospitals NHS

Trust,

Department of Nutrition & Dietetics,

Hammersmith Hospital,

Du Cane Road,

London W12 0HS, UK.

Tel.: +44 20 83833048

Fax: +44 20 83833379

E-mail: g.frost@ic.ac.uk

Keywords

catering, food, hospital, nutritional

intake.

Accepted

May 2000

Background Malnutrition affects between 25 and 40% of all

hospitalized patients, the majority of whom receive their main

nutritional intake from the food provided by the hospital catering

system. There is currently very little published information concerning

the nutritional impact on patients of different methods of catering

service.

Objective In the current study the effects of two catering service

systems, plated and bulk service, on food and nutrient intake of

hospital patients were compared.

Methods One-hundred and eight patient meals were surveyed, 51 on

the plated meal and 57 on the bulk meal services. Patients were either

on a general medical or an orthopaedic ward. Weighed food intake data

were collected by weighing food served and comparing it to the weight

of food left on the plate. Equal numbers of lunch and supper dishes

were weighed. Also, a number of weekend surveys were carried out to

take into account variation in service at weekends.

Results Food wastage was greater with the plated system. Comparing

the amount of energy and nutrients consumed by patients according to

meal system: energy intakes were significantly lower with the plated

system (414 6 23 kcal vs. 319 6 22 kcal, P , 0.004). Protein, fat and

carbohydrate intakes were also significantly lower. The main reason for

the observed differences was the higher total food intake of the main

course of the bulk service meals. Energy intake from the main course

was significantly higher among patients receiving bulk service meals

(227 6 10 kcal vs. 165 6 14 kcal, P , 0.006).

Conclusion Catering service systems can have a major impact on the

nutritional intake of hospitalized patients.

Introduction

A consistent finding across many studies is that a

large proportion of hospital inpatients are malnourished (Bistrian et al., 1976; Hill et al., 1977;

Larsson et al., 1990; Moy et al., 1990). Classic work

by Pennington et al. has demonstrated that not only

Blackwell Science Ltd 2000 J Hum Nutr Dietet, 13, pp. 271275

are there are a large number of patients admitted in

a malnourished state, but that this becomes worse

over inpatient stay (McWhirter & Pennington,

1994). Influential reports such as the Kings Fund

Report `A positive approach to nutrition in the

hospitalized patients', and the more recent economic evaluation of treatment of malnutrition,

271

272

A. Wilson et al.

point to the possibilities of large financial savings

(226 million according to the Kings Fund) by

treating this problem (Lennard-Jones, 1992), savings mainly being made through decreased hospital

stay and treatment costs. Although artificial nutrition has received attention in published work, by far

the majority of patients will receive most of their

nutritional intake from the food provided by the

hospital catering system. Recent data concerning

feeding practice show that per 100 hospital beds,

0.6% are fed by parenteral nutrition, 2.1% by tube

feeding, 8.1% receive supplements and 89% rely on

hospital food (Elia et al., 1996). This has led

organizations such as the British Enteral and

Parenteral Nutrition Society, and the Nuffield Trust

to recommend that there should be a multidisciplinary committee within the hospital that will

advise on all aspects of nutritional needs of patients

(Allison, 1999; Davis & Bristow, 1999).

There is very little systematic evaluation of

hospital catering systems and their effect on

patients' nutritional intake. Our own work both

on the introduction of a healthy eating policy and

on the effect of nutritional supplementation show

nutrient intakes to be poor in the most vulnerable

groups (Frost et al., 1991; Hogarth et al., 1996).

Most evaluation of these systems concerns economic capital costs of the system and the running costs

thereafter. There is little work on economic aspects

of the acceptability of the food, the effect of systems

to provide a nutritionally adequate intake or an

evaluation of food wastage. This possibly reflects the

difficulty in building economic models to assess the

balance between capital outlay and the ability of a

system to decrease food wastage, increase patient

intake and decrease malnutrition. However, with

the publication of reports such as `Hungry in

hospital' and `Eating Matters', the quality of food

systems is beginning to be questioned (Association

of Community Health Councils for England &

Wales, 1997).

On-going evaluation of the meal service within

The Hammersmith Hospitals NHS Trust had

shown the need to be concerned over the quality

of the food reaching the patients using a plated food

service. In an attempt to improve meal service to

patients at Charing Cross hospital (CXH), an

evaluation of a bulk trolley meal service was

introduced. This study evaluates the pilot period

for the introduction of a bulk trolley meal service

against the traditional meal service and investigates

the effect it had on patient nutritional intake.

Methods

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect on

nutritional intake of a pilot introduction of a bulk

trolley system compared to the traditional plated

food system at CXH. This was a unique opportunity

as the introduction was limited to the type of meal

service, the method of food preparation (cook-chill)

was to remain the same and the menu cycle

remained the same. This study is part of the ongoing catering monitoring and audit and was not

subject to ethical approval.

Centrally plated meal service. This was the

traditional method of meal service at Charing Cross

Hospital. Menu cards are filled in at ward level, then

collected centrally in the catering department and

the meals are then plated-up on a belt-run. Once

plated, the meals are transported to the ward in

trolleys. The meals are then regenerated on the plate

and served to the patients directly.

Bulk trolley. Again menu cards are filled in at

ward level and collected centrally. These menu cards

are then used to estimate the bulk supply of food for

the ward. Containers with the approximate amount

of each food item are transported to the ward and

regenerated in bulk. The food is then plated from a

hostess trolley at ward level taking into account

patients' preference and portion required. This

system also allows patients to change their mind

over the choice of menu at point of service. It also

integrates more nursing staff into the meal service.

Patients

One hundred and eight patient meals were

surveyed, 51 on the plated meal and 57 on the

bulk meal services. Patients were on either a general

medical or an orthopaedic ward. Equal numbers on

each ward were surveyed. No patient was on a

`special diet' or had a recorded problem eating. As

Blackwell Science Ltd 2000 J Hum Nutr Dietet, 13, pp. 271275

Meal services and nutrient intake

the menu and the type of food were the same, it was

possible to survey the meals before and after the

introduction of the bulk trolley, at the same time in

the menu cycle, so controlling for change in food

reheating method alone.

Nutrient analysis

This was carried out using Dietplan 5 (Forest Hill

Software, UK) computerized food tables. These

tables use the Composition of Foods 5th edn and the

current supplements.

Weighed food intake

Statistics

In both plated and bulk services, each food item was

weighed as it was put onto the plate. In the case of

the plated service this was in the plating room in the

central kitchen, in the case of bulk service this was

at ward level. Patients were then served their meals

in the normal way. After they had finished eating

the waste was weighed. Each individual food item

was weighed to the nearest 5 g on the same

electronic scale. Each item was weighed as it was

put onto the patient's plate so as not to affect

appearance of the meal. Cumulative weights were

calculated at a later date. Equal numbers of lunch

and supper dishes were weighed. Also, a number of

weekend surveys were carried out to take into

account variation in service at weekends.

All results are expressed as means (SEM). All data

were normally distributed so comparisons within or

between groups was by Student's t-test.

Results

The results are summarized in Table 1. There was

no significant difference in the nutrient content of

the food served to the patients on either the plated

or the bulk systems. The food served at an average

meal by both systems met the NHS Guidelines

(Nutrition Task Force Hospital Catering Team,

1995), i.e. 300500 kcal energy and 1218 g protein

per meal. In both the bulk and the plated system,

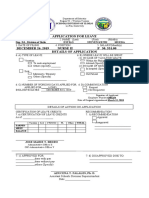

Table 1 A comparison of the amount of food served and consumed according to meal service system. Results are expressed as the mean

and SEM

Served

Meal

service

system

Plated

Bulk

Consumed

Meal

breakdown

Amount

(g)

Protein

(g)

Fat

(g)

CHO

(g)

Energy

(cal)

Energy

(kJ)

Amount

(g)

Protein

(g)

Fat

(g)

CHO

(g)

Energy

(cal)

Energy

(kJ)

Total

SEM

Dessert

SEM

Starter

SEM

Main

SEM

Total

SEM

Dessert

SEM

Starter

SEM

Main

SEM

541

16

145

8

131

6

246

14

532

17

133

8

137

7

238

12

22

1

4

0

1

0

17

1

21

1

4

0

1

0

16

1

19

1

7

1

0

0

12

1

19

1

6

1

1

0

12

1

64

2

27

2

6

0

27

2

59

2

24

2

7

0

24

2

499

19

178

15

32

1

270

15

478

20

155

13

37

2

258

13

2099

80

750

16

137

6

1133

63

2010

83

653

54

158

8

1085

52

360{

21

120{

9

121

6

165{

14

455{*

20

125

8

132

8

227*

10

14{

1

4

0

1

0

11{

1

18{*

1

3

0

1

0

14*

1

11{

1

5

1

0

0

7{

1

16{*

1

5

1

0

0

11*

1

41{

3

22

2

6

0

18{

2

51{*

3

22

2

7

0

24*

2

319{

22

146{

14

30

2

178{

15

414{*

23

145

13

35

2

246*

15

1345{

92

617

57

128

7

752{

62

1744{*

96

610

53

149

8

1035*

61

{Denotes a significant difference within group of at least P < 0.05; *denotes a significant difference between groups of at least P < 0.05.

Blackwell Science Ltd 2000 J Hum Nutr Dietet, 13, pp. 271275

273

274

A. Wilson et al.

not all food was consumed. Wastage was minor in

the case of the bulk trolley system with 87% of food

eaten, whereas 65% was eaten with the plated

system. It is interesting that the main component of

this difference was the main course, 95% of which

was eaten in the case of the bulk system and 67%

with the plated system (P , 0.01). In comparing

the amount of nutrients consumed between the two

systems, there was significantly less eaten with the

plated system in terms of energy (414 6 23 kcal vs.

319 6 22 kcal, P , 0.004), protein (18 6 1 g vs.

14 6 1 g, P , 0.002), fat (16 6 1 g vs. 11 6 1 g,

P , 0.003) and carbohydrate (51 6 3 g vs.

41 6 3 g, P , 0.01).

The main reason for the observed differences was

the high intake in the main course of the bulk

service meal in terms of energy (227 6 10 kcal vs.

165 6 14 kcal, P , 0.006), protein (14 6 1 g vs.

11 6 1 g, P , 0.001), fat (16 6 1 g vs. 11 6 1 g,

P , 0.006) and carbohydrate (24 6 2 g vs.

18 6 2 g, P , 0.006).

Discussion

The main aim for providing a meal service to people

in hospital is to maintain their nutritional status

over a vulnerable period of their life in order to

reduce morbidity and mortality. There appears to

be no published comparison of the effect that the

introduction of changes in catering systems can

have on the nutritional intake of patients, which

would suggest that the primary goal of feeding

people has been forgotten in the list of considerations when new systems are being considered.

Although the meal service in both systems met

the nutritional guidelines for hospital catering

(Nutrition Task Force Hospital Catering Team,

1995), the real issue is the amount that is

consumed. A system may deliver the right mix of

nutrients, but if the food is not eaten it has failed.

This seems to be what is happening to the main

course on the plated system. At the present time this

is not taken into account in catering standards.

Our study has demonstrated that the type of meal

service can make a large difference to patients' food

intake. The pilot assessment of the bulk system

showed it to produce a greater nutrient intake

mainly as a result of the large amount of the main

course being consumed. The reasons for this

increase are unknown as no patient acceptability

data were collected at this time. The observed

differences were the plate presentation and the

greater degree of flexibility on portion size with the

bulk trolley system.

Other aspects of the bulk system which may play

a part are hard to quantify, e.g. more nurses were

involved in the meal service and there was more

contact with patients at meal times.

Obviously, if the full-scale implementation of a

bulk trolley system was to produce a similar

reduction in waste and increase in nutritional

intake of patients, the potential significantly to

affect length of patient stay and decrease morbidity

becomes a realistic goal.

There is a need to evaluate catering systems not

just from the purely financial view point but also

from a nutritional point of view. There is a need to

develop a methodology to carry this out in a

systematic way so that valid comparisons can be

made between different systems and institutions.

References

Allison, A. (1999) Hospital Food as a Treatment. Maidenhead:

BAPEN.

Association of Community Health Councils for England and

Wales. (1997) Health News Briefing Hungry in Hospital?

Community health Council.

Bistrian, B.R., Blackburn, G.L., Vitale, J., Cochran, D. &

Naylor, J. (1976) Prevalence of malnutrition in general

medical patients. JAMA 235, 15671570.

Davis, A.M. & Bristow, A. (1999) Managing Nutrition in

Hospital. A recipe for Quality. 8. Nuffield Trust Series.

London: Nuffield Trust.

Elia, M., Micklewright, A., Shaffer, J., Wood, S., Russell, C.,

Wheatley, C. & Scott, D. (1996) The 1996 Annual Report

of the British Artificial Nutrition Survey, 119. BANS.

Frost, G., Elston, C., Masters, K. & de Swiet, M. (1991) Effect

of the introduction of a food and health policy on the

nutritional intake of hospitalised patients. J. Hum Nutr.

Dietet. 4, 191197.

Hill, G.L., Blackout, R.L., Pickford, I., Burkinshaw, L., Young,

G.A., Warren, J.V., Schorah, C.J. & Morgan, D.B. (1977)

Malnutrition in surgical patients. An unrecognised

problem. Lancet 1, 689692.

Hogarth, M.B., Marshall, P., Lovat, L.B., Palmer, A.J., Frost,

G., Fletcher, A.E., Nicholl, C.G. & Bulpitt, C.J. (1996)

Nutritional supplementation in elderly medical inpatients: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Age.

Ageing 25, 453457.

Blackwell Science Ltd 2000 J Hum Nutr Dietet, 13, pp. 271275

Meal services and nutrient intake

Larsson, J., Unosson, M., Ek, A.C., Nilsson, L., Thorslund, S.

& Jurulf, P. (1990) Effect of dietary supplement on

nutritional status and clinical outcomes in 501 geriatric

patients a randomised study. Clin. Nutr. 9, 179184.

Lennard-Jones, J.E. (1992) A Postive Approach to Nutrition as

Treatment. a Report on the Role of Enteral and Parenteral

Feeding in Hospital and at Home. London: King's Fund

Centre.

McWhirter, J.P. & Pennington, C.R. (1994) Incidence and

Blackwell Science Ltd 2000 J Hum Nutr Dietet, 13, pp. 271275

recognition of malnutrition in hospital. Br. Med. J. 308,

945948.

Moy, R.J.D., Smallman, S. & Booth, I.W. (1990) Malnutrition in a UK childrens hospital. J. Hum. Nutr. Dietet. 3,

93100.

Nutrition Task Force Hospital Catering Team. (1995).

Nutrition Guidelines for Hospital Catering. London:

Department of Health.

275

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- CGH:2018 09 13:maravillaDocumento3 páginasCGH:2018 09 13:maravillaRachelle MaravillaAinda não há avaliações

- Phenobarbital, Phenytoin, Rifampin: May: Increase Rate of Donepezil Elimination. Increase Gastric Acid SecretionsDocumento4 páginasPhenobarbital, Phenytoin, Rifampin: May: Increase Rate of Donepezil Elimination. Increase Gastric Acid SecretionsKim Glaidyl BontuyanAinda não há avaliações

- Reverse PharmacologyDocumento7 páginasReverse PharmacologyNithish BabyAinda não há avaliações

- Leave Form Sample DepedDocumento1 páginaLeave Form Sample Depedsteven keith EstiloAinda não há avaliações

- Writing Nursing Sample Test 1 PDFDocumento5 páginasWriting Nursing Sample Test 1 PDFKajal RabariAinda não há avaliações

- Corp HR Policy - TB July 2014 PDFDocumento4 páginasCorp HR Policy - TB July 2014 PDFDyey AlarconAinda não há avaliações

- Irr of Republic Act No 9442Documento11 páginasIrr of Republic Act No 9442Jacqueline Carlotta SydiongcoAinda não há avaliações

- Control of Communicable Diseases Manual 19th EditiDocumento3 páginasControl of Communicable Diseases Manual 19th EditiheladoAinda não há avaliações

- Forgotten Transvaginal Cervical Cerclage Stitch in First Pregnancy Benefits Reaped Till The Second PregnancyDocumento2 páginasForgotten Transvaginal Cervical Cerclage Stitch in First Pregnancy Benefits Reaped Till The Second PregnancyAna AdamAinda não há avaliações

- 2015 AGPT Applicant Guide WebDocumento82 páginas2015 AGPT Applicant Guide WebNajia ChoudhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Wound AssessmentDocumento3 páginasNursing Wound AssessmentMatthew RyanAinda não há avaliações

- Unit Allotment Obg Gnm3rdyearDocumento3 páginasUnit Allotment Obg Gnm3rdyeartarangini mauryaAinda não há avaliações

- Gastroenteritis Leaflet FinalDocumento2 páginasGastroenteritis Leaflet FinalRiony GusbaniansyahAinda não há avaliações

- Biopharmaceutics Uos Past PapersDocumento9 páginasBiopharmaceutics Uos Past PapersMr nobodyAinda não há avaliações

- Organ Donation Act of 1991: Prepared By: Dayle Daniel Sorveto, RMTDocumento10 páginasOrgan Donation Act of 1991: Prepared By: Dayle Daniel Sorveto, RMTRC SILVESTREAinda não há avaliações

- Adobe Scan Apr 03, 2023Documento45 páginasAdobe Scan Apr 03, 2023Dhruv VasudevaAinda não há avaliações

- High-Alert Medications For Pediatric Patients: An International Modified Delphi StudyDocumento12 páginasHigh-Alert Medications For Pediatric Patients: An International Modified Delphi StudyEman MohamedAinda não há avaliações

- Makerere University Mature Age Entry Government Sponsorship 2020/2021Documento6 páginasMakerere University Mature Age Entry Government Sponsorship 2020/2021The Campus TimesAinda não há avaliações

- Apollo Case Study - 0 PDFDocumento18 páginasApollo Case Study - 0 PDFVisweswar AnimelaAinda não há avaliações

- Gmail - Gloria Korany 5-23-23Documento2 páginasGmail - Gloria Korany 5-23-23Anthony DocKek PenaAinda não há avaliações

- Feedback FormsDocumento26 páginasFeedback FormsLea MateoAinda não há avaliações

- Dental NLE 2021 Syllabus - FinalDocumento55 páginasDental NLE 2021 Syllabus - FinalJohn frostAinda não há avaliações

- Name: - Date: - Grade and Section: - ScoreDocumento2 páginasName: - Date: - Grade and Section: - Scoregabby ilaganAinda não há avaliações

- Perkembangan FE Di UMPDocumento11 páginasPerkembangan FE Di UMPrsud bung karnoAinda não há avaliações

- Weekly Influenza Surveillance Update 2020-2021 From The Rhode Island Department of Health.Documento29 páginasWeekly Influenza Surveillance Update 2020-2021 From The Rhode Island Department of Health.Frank MaradiagaAinda não há avaliações

- PHC 1.fDocumento74 páginasPHC 1.fWynjoy NebresAinda não há avaliações

- Marfan Syndrome and DentistryDocumento4 páginasMarfan Syndrome and Dentistryapi-311788459Ainda não há avaliações

- Admission Committee For Professional CouresesDocumento11 páginasAdmission Committee For Professional CouresesRohit patelAinda não há avaliações

- BT 703 D NKJ Lecture 7 DevelopmentDocumento3 páginasBT 703 D NKJ Lecture 7 DevelopmentSumanta KarAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Gawat DaruratDocumento17 páginasJurnal Gawat Daruratlucia lista100% (2)