Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Biliary Cysts

Enviado por

Daniel PintoDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Biliary Cysts

Enviado por

Daniel PintoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Biliary cysts

1 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Official reprint from UpToDate

www.uptodate.com 2016 UpToDate

Biliary cysts

Author

Mark Topazian, MD

Section Editors

Sanjiv Chopra, MD, MACP

Elizabeth B Rand, MD

Deputy Editor

Anne C Travis, MD, MSc, FACG,

AGAF

All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review process is complete.

Literature review current through: Jun 2016. | This topic last updated: Feb 06, 2015.

INTRODUCTION Biliary cysts are cystic dilations that may occur singly or in multiples throughout the biliary tree.

They were originally termed choledochal cysts due to their involvement of the extrahepatic bile duct. However, the

original clinical classification [1] was revised in 1977 to include intrahepatic cysts [2]. Biliary cysts are associated with

significant complications such as ductal strictures, stone formation, cholangitis, rupture, and secondary biliary

cirrhosis. In addition, certain types of biliary cysts have a high risk of malignancy.

This topic will review the pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management of biliary cysts.

Cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer, and a detailed discussion of type V biliary cysts (Caroli disease) are

discussed elsewhere. (See "Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and classification of cholangiocarcinoma" and "Pathology

of malignant liver tumors" and "Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma" and "Treatment of

localized cholangiocarcinoma: Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy and prognosis" and "Gallbladder cancer:

Epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features, and diagnosis" and "Caroli disease".)

TYPES OF BILIARY CYSTS A classification scheme for cysts of the extrahepatic bile ducts (choledochal cysts)

was proposed initially in 1959 [1]. It was expanded in 1977 to include intrahepatic cysts [2] and further refined in

2003 to incorporate the presence of an abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ) [3]. (See 'Abnormal

pancreatobiliary junction' below.)

The classification scheme defines five types of biliary cyst (figure 1) [3-5]:

Type I cysts (50 to 85 percent of cysts) Type I cysts are characterized by cystic or fusiform dilation of the

common bile duct (image 1) [2,6]. Type I cysts do not involve the intrahepatic bile ducts. Type I cysts are further

subcategorized as [3]:

Type IA Cystic dilation of the common bile duct, as well as part or all of the common hepatic duct and

extrahepatic portions of the left and right hepatic ducts. Type IA cysts are associated with an APBJ. The

cystic duct and gallbladder arise from the dilated common bile duct.

Type IB Focal, segmental dilation of an extrahepatic bile duct (often the distal common bile duct). Type

IB cysts are not associated with an APBJ.

Type IC Smooth, fusiform (as opposed to cystic) dilation of all the extrahepatic bile ducts. Typically, the

dilation extends from the pancreatobiliary junction to the extrahepatic portions of the left and right hepatic

ducts. Type IC cysts are associated with an APBJ.

Type II cysts (2 percent of cysts) Type II cysts are true diverticula of the extrahepatic bile ducts and

communicate with the bile duct through a narrow stalk. They may arise from any portion of the extrahepatic bile

duct.

Type III cysts (1 to 5 percent of cysts) Type III cysts are cystic dilations limited to the intraduodenal portion of

the distal common bile duct and are also known as choledochoceles (figure 2). Type III cysts can be lined by

duodenal or biliary epithelium and may arise embryologically as duodenal duplications involving the ampulla.

As many as five subtypes have been described [7]; however, most commonly they are subdivided into two

types [8-11]:

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

2 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Type IIIA The bile duct and pancreatic duct enter the cyst, which then drains into the duodenum at a

separate orifice.

Type IIIB A diverticulum of the intraduodenal common bile duct or intra-ampullary common ductal

channel.

Type IV cysts (15 to 35 percent of cysts) Type IV cysts are defined by the presence of multiple cysts and are

subdivided based on their intrahepatic bile duct involvement:

Type IVA Both intrahepatic and extrahepatic cystic dilations. Type IVA is the second most common type

of biliary cyst and is often associated with a distinct change in duct caliber and/or a stricture at the hilum,

features that help differentiate it from a type IC cyst [3].

Type IVB Multiple extrahepatic cysts but no intrahepatic cysts.

Type V cysts (20 percent of cysts) Type V cysts are characterized by one or more cystic dilations of the

intrahepatic ducts, without extrahepatic duct disease. The presence of multiple saccular or cystic dilations of

the intrahepatic ducts is known as Caroli disease. (See "Caroli disease".)

This classification system does not include rare cases of cystic duct cysts.

EPIDEMIOLOGY The incidence of biliary cysts in Western populations has been estimated to be 1:100,000 to

1:150,000 [6]. The incidence is higher in some Asian countries (up to 1:1000) [12], with between one-half and

two-thirds of the reported cases occurring in Japan [6,12]. A report from Finland suggests that the incidence of biliary

cysts has increased from 1:128,000 to 1:38,000 over the past 40 years [13]. Biliary cysts are more common in

women, with a female to male ratio of 3:1 to 4:1 [2,5,12]. In the past, the majority of cases were reported in children,

although more recent series report equal numbers in adults and children [14].

PATHOGENESIS Several theories of biliary cyst formation have been proposed, and it is likely that no one

mechanism accounts for all biliary cysts [5]. In many patients, an abnormal pancreatobiliary junction appears to play

an important role. (See 'Abnormal pancreatobiliary junction' below.)

Cysts may be congenital [15] or acquired [16] and have been associated with a variety of anatomic abnormalities. A

genetic or environmental predisposition to biliary cysts is suggested by reports of the familial occurrence of cysts [17]

and by the increased incidence in some Asian countries.

Associated conditions Developmental anomalies associated with biliary cysts include:

Abnormal pancreatobiliary junction

Biliary atresia

Duodenal atresia

Colonic atresia

Imperforate anus

Pancreatic arteriovenous malformation

Multiseptate gallbladder

Hemifacial microsomia with extracraniofacial anomalies (OMENS plus syndrome)

Ventricular septal defect

Aortic hypoplasia

Congenital absence of the portal vein

Heterotopic pancreatic tissue

Familial adenomatous polyposis

Autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

Congenital cysts Congenital cysts may result from an unequal proliferation of embryologic biliary epithelial cells

before bile duct cannulation is complete [18,19]. Fetal viral infection may also have a role, as reovirus ribonucleic

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

3 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

acid (RNA) has been isolated from biliary tissue of neonates with infantile biliary obstruction and biliary cysts [20]. In

addition, cyst formation may be the result of ductal obstruction or distension during the prenatal or neonatal period.

In a sheep model, bile duct ligation in neonates led to cyst formation, whereas duct ligation in adult animals led to

gallbladder distension [21].

Abnormal pancreatobiliary junction Some biliary cysts may be the result of an abnormal pancreaticobiliary

junction (APBJ), also called pancreaticobiliary maljunction or malunion. The APBJ may allow reflux of pancreatic

juice into the biliary tree with resultant damage to the biliary epithelium and cyst formation.

While APBJ is a rare congenital anomaly, with a prevalence of 0.03 percent in one population-based series from

Japan [22], it is present in 50 to 80 percent of patients with biliary cysts (image 2 and picture 1 and image 1) [23]. An

APBJ may also be a significant risk factor for the development of malignancy within a biliary cyst [24] or the

gallbladder [25]. (See 'Abnormal pancreatobiliary junction and cancer' below.)

APBJ is characterized by a junction of the bile duct and pancreatic duct outside the duodenal wall with a long

common ductal channel leading to the duodenal lumen (at least 8 mm, and often over 20 mm, in length) [25,26].

APBJ may result from failure of the embryological ducts to migrate fully into the duodenum. In support of this

hypothesis is the observation that the ampulla of Vater is diminutive or flat in patients with APBJ. In one series, the

papilla was displaced distally in the duodenum of patients with APBJ, with the distal displacement of the papilla

corresponding to the length of the common channel [27].

A long common channel may predispose to reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary tree since the ductal junction lies

outside of the duodenal wall and the sphincter of Oddi [28]. This can result in increased amylase levels in bile [29],

intraductal activation of proteolytic enzymes, and alterations in bile composition. These changes in the composition

of bile could theoretically lead to biliary epithelial damage with inflammation, ductal distension, and eventually, cyst

formation. Elevated sphincter of Oddi pressures have been documented in APBJ and could promote

pancreaticobiliary reflux [30,31].

HISTOLOGY Histologic features of biliary cysts are variable, ranging from normal bile duct mucosa to carcinoma

[6,32]. More commonly in children, there is a densely fibrotic cyst wall with evidence of chronic and acute

inflammation [6]. In adults, there are frequently inflammatory changes, erosions, sparse distribution of mucin glands,

and not infrequently, metaplasia and biliary intraepithelial neoplasia, precursors of cholangiocarcinoma [6,33,34].

Malignancy, when present, is most commonly found in the posterior cyst wall [32]. In the case of type III cysts, the

cyst is usually lined by duodenal mucosa and less commonly by bile duct epithelium [8]. (See 'Types of biliary cysts'

above.)

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Presentation The majority of patients with biliary cysts will present before the age of 10 years [35]. The classic

presentation includes the triad of abdominal pain, jaundice, and a palpable mass, and is more common in children

than adults [36]. However, the majority of patients will only have one or two elements of the triad [6,37]. Patients may

also report nausea, vomiting, fever, pruritus, and weight loss. Neonates typically present with obstructive jaundice

and abdominal masses whereas adults frequently present with pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice [35].

Biliary cysts may also be an incidental finding during prenatal ultrasonography or in an asymptomatic patient who is

undergoing imaging or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for other reasons.

Patients may also present with signs and symptoms related to complications associated with biliary cysts, including

pancreatitis, cholangitis, and obstructive jaundice. (See 'Complications other than cancer' below.)

Laboratory tests Serum liver tests are often normal in patients with biliary cysts. In the presence of an

obstructing stone, stricture, or malignancy, serum liver tests will typically be elevated in a cholestatic pattern

(disproportionate elevations of the alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and bilirubin relative to

the aminotransferases). Laboratory evidence of complications may also be present (eg, elevated pancreatic

enzymes with pancreatitis, elevated white blood cell count with cholangitis). (See 'Complications other than cancer'

below.)

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

4 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Cancer risk Biliary cysts are associated with an increased risk of cancer, particularly cholangiocarcinoma [38].

Cancer is more common in patients who are older and in those with type I and IV cysts. Because of the increased

risk of malignancy, it is recommended that patients with type I or IV cysts have the cysts completely removed with

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. The risk of cancer appears to be lower in patients with type II or III cysts. Patients

with type II cysts can often be treated with simple cyst excision, while those with type III cysts can be treated with

sphincterotomy or endoscopic resection [11]. Patients with type V cysts have a moderate risk of cancer, but because

of the intrahepatic nature of the cysts, treatment can be difficult and some patients require liver transplantation. (See

'Management' below and "Caroli disease", section on 'Treatment'.)

Overall, the incidence of cancer is reported to be in the range of 10 to 30 percent with a mean age at diagnosis of 32

years [38,39]. However, the cited statistics likely overestimate the risk of cancer in biliary cysts because most series

include only symptomatic patients presenting with complications, including malignancy. To calculate the true risk of

malignant degeneration, the incidence of asymptomatic biliary cysts in the population should be used as the

denominator, a value that is unknown. If patients who developed malignancy at least two years after initial diagnosis

of their cyst are studied, the incidence appears lower (4.5 percent rather than 14 percent in one series) [33].

Nevertheless, evidence clearly points to a 20- to 30-fold increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma in biliary cysts

compared with the general population [38]. This evidence includes the occurrence of cholangiocarcinoma in patients

as young as 10 years of age [40], the occurrence of synchronous and metachronous biliary cancers, and the

subsequent development of cancer in patients with incompletely resected cysts [41,42]. The possibility of cancer

should always be considered in an adult with a newly diagnosed biliary cyst.

Age The incidence of malignancy increases with age. In a 2014 review of all published series of biliary cysts,

the incidence of cancer was 0.4 percent in patients under 18 years of age and 5 percent in patients 18 to 30 years of

age. The incidence continued to increase with each decade of life, reaching 38 percent in patients over 60 years of

age [43]. Some studies have reported a cancer incidence as high as 50 percent in older patients [40].

Cyst type Most cancers occur in type I and type IV cysts. In one series, 68 percent of the malignancies

occurred in patients with type I cysts, and 21 percent occurred in patients with type IV cysts [44]. Patients with type II

cysts and type III cysts accounted for 5 and 2 percent of cases, respectively. Cancer in patients with type III cysts

may be limited to those with cysts lined by biliary, rather than duodenal, epithelium [45]. Type V cysts (Caroli

disease) have also been associated with a 7 to 15 percent risk of malignancy [5,38,46]. Multiple studies have

described molecular changes that occur during the evolution to malignancy, but their role in diagnosis or

management is unclear [38].

Abnormal pancreatobiliary junction and cancer The presence of an abnormal pancreatobiliary junction

(APBJ) increases the risk of malignancy. In one study, the increased incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in biliary cysts

was confined to patients with an APBJ [24]. In addition, APBJ appears to increase the risk of biliary and pancreatic

malignancy, even in patients without a biliary cyst or ductal dilation [47-50]. K-ras mutations and p53 overexpression

have been demonstrated in the biliary mucosa of such patients [51]. Gallbladder cancer is the most common

malignancy seen in patients with APBJ who do not have a biliary cyst, and prophylactic cholecystectomy in patients

with APBJ has been advised [49]. Surveillance of the bile duct may be warranted after cholecystectomy [52]. (See

"Gallbladder cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features, and diagnosis", section on 'Abnormal

pancreaticobiliary duct junction'.)

Complications other than cancer Nonmalignant complications of biliary cysts include [6,23,35,37]:

Cystolithiasis (stone and sludge formation in the cyst)

Cholelithiasis

Choledocholithiasis

Hepatolithiasis

Cholangitis

Acute and chronic pancreatitis

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

5 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Intraperitoneal cyst rupture

Secondary biliary cirrhosis due to prolonged biliary obstruction and recurrent cholangitis

Bleeding due to erosion of the cyst into adjacent vessels or as the result of portal hypertension

Gastric outlet obstruction due to the obstruction of the duodenal lumen

Intussusception

Stones and pancreatitis are more commonly encountered in patients with type III cysts.

DIAGNOSIS A biliary cyst should be considered when a dilated portion of the bile duct or ampulla is identified on

imaging, especially in the absence of biochemical, radiographic, or endoscopic evidence of obstruction. A high level

of suspicion is required for diagnosis, particularly for type I cysts, which may go undiagnosed unless considered in

the differential diagnosis of patients found to have ductal dilation. The diagnosis can typically be made with a

combination of transabdominal ultrasonography and cross-sectional imaging. Additional testing may be required to

rule out biliary obstruction (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP], magnetic resonance imaging

[MRI], or endoscopic ultrasound [EUS]) or to confirm communication of the cyst with the biliary tree (hepatobiliary

scintigraphy or ERCP).

Diagnostic approach Patients suspected of having biliary cysts should undergo an evaluation to confirm the

presence of the cysts and to determine whether there is communication between the cysts and the biliary tree. Cysts

are often first suspected based on the findings from transabdominal ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT)

in a patient being evaluated for abdominal pain, jaundice, or an abdominal mass. With the widespread use of CT and

MR, ,many cysts are now discovered incidentally during abdominal imaging performed for an unrelated reason. It is

important to consider a biliary cyst in a patient found to have a dilated bile duct or cystic liver lesion(s). (See 'Clinical

manifestations' above and "Diagnostic approach to the adult with jaundice or asymptomatic hyperbilirubinemia",

section on 'Diagnostic evaluation' and "Diagnosis and management of cystic lesions of the liver".)

If a cyst is suspected based on an ultrasound, cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI with magnetic resonance

cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is typically the next step in diagnosis. Cross-sectional imaging can confirm the

presence of a cyst, determine if the cyst communicates with the biliary tree, and evaluate for an associated mass.

MRI/MRCP is more expensive, but is often preferred because it does not use ionizing radiation and can assess for

an obstruction lesion within the biliary tree or pancreas. (See 'Transabdominal ultrasound' below and 'Computed

tomography' below and 'Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography' below.)

Following cross-sectional imaging, some patients will require additional testing:

Types I and IVA cysts If concern remains for an obstruction following MRCP (eg, because the liver tests are

elevated in a cholestatic pattern), an ERCP or EUS should be performed. These tests provide direct

visualization of the ampulla as well as the peri-ampullary bile duct and pancreatic duct. (See 'ERCP and other

forms of direct cholangiography' below and 'Endoscopic ultrasound' below.)

Types II and IVB cysts If it is unclear whether the cyst communicates with the biliary tree after cross-sectional

imaging, confirmation may be obtained by hepatobiliary scintigraphy, ERCP, or EUS. EUS may be particularly

helpful for distinguishing a pancreatic head cyst from a Type II biliary cyst [53]. (See 'Hepatobiliary scintigraphy'

below and 'ERCP and other forms of direct cholangiography' below.)

Type III cysts ERCP can confirm the presence of a type III cyst and permits endoscopic therapy during the

same examination. (See 'Type III cysts' below.)

Type V cysts Typically, the diagnosis is established when imaging studies demonstrate intrahepatic bile duct

ectasia and irregular, cystic dilation of the large proximal intrahepatic bile ducts with a normal common bile

duct. Rarely, liver biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis. (See "Caroli disease", section on 'Diagnosis'.)

Percutaneous or intraoperative cholangiography (alternatives to ERCP) can also be performed to examine the biliary

tree, but are rarely needed. (See "Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography".)

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

6 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Imaging test characteristics Multiple imaging modalities are available to evaluate biliary cysts, including

transabdominal ultrasound, CT, MRCP, ERCP, EUS, and hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Which test(s) to obtain will

depend on the patient's presentation and prior testing. (See 'Diagnostic approach' above.)

Transabdominal ultrasound Transabdominal ultrasound has a sensitivity of 71 to 97 percent for diagnosing

biliary cysts [54]. Factors that may limit the usefulness of an ultrasound include the patient's body habitus, the

presence of bowel gas, and limited visualization due to overlying structures. Ultrasound frequently misses type III

cysts [55].

Communication with the biliary tree must be demonstrated in order to differentiate biliary cysts from other cystic

lesions (eg, typical simple liver cysts). While ultrasound may show communication with the bile duct [56], the findings

are typically confirmed with other imaging modalities (eg, CT, MRCP, ERCP, or scintigraphy).

Computed tomography CT can detect all types of biliary cysts. It can demonstrate continuity of the cyst with

the biliary tree, examine the relationship of the cyst to surrounding structures, and evaluate for the presence of

malignancy. It is also useful for determining the extent of intrahepatic disease in patients with type IVA or V cysts.

(See "Computed tomography of the hepatobiliary tract".)

Computed tomographic cholangiography has been used to delineate the anatomy of the biliary tree and has high

sensitivities for visualizing the biliary tree (93 percent), diagnosing biliary cysts (90 percent), and diagnosing

intraductal stones (93 percent) [57]. However, its sensitivity is lower for imaging the pancreatic duct (64 percent).

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography MRCP does not expose patients to ionizing radiation and

does not have the risks of cholangitis and pancreatitis associated with ERCP. In many cases, it is the test of choice

for diagnosing and evaluating biliary cysts. Its sensitivity for biliary cysts is between 73 and 100 percent [58].

However, MRCP is less sensitive than direct cholangiography for excluding obstruction. The data are variable with

regard to its ability to diagnose an abnormal pancreatobiliary junction. Some studies have found that it identifies an

abnormal pancreatobiliary junction in over 75 percent of cases [58-60], whereas the rate has been as low as 46

percent in other studies [35]. (See "Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography".)

ERCP and other forms of direct cholangiography Direct cholangiography (endoscopic, percutaneous or

intraoperative) has a sensitivity of up to 100 percent for diagnosing biliary cysts [61]. Type III cysts are often first

suspected during ERCP when a dilated intramural portion of the bile duct is seen endoscopically. The dilated

segment may become much more apparent during contrast injection, ballooning in shape as it fills with contrast.

Cholangiography allows for preoperative evaluation of the biliary anatomy, can identify an abnormal pancreatobiliary

junction, and can detect filling defects due to stones or malignancy. However, ERCP may miss malignant strictures

in the proximal portion of a type I cyst, unless attempts are made to cannulate and fill the intrahepatic bile ducts and

biliary confluence. Complications of cholangiography include cholangitis and pancreatitis [62-64]. Patients with cystic

disease are at greater risk for these complications compared with the general population due to the presence of long

common channels, dysfunctional sphincters, and dilated ducts [62]. (See "Endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography: Indications, patient preparation, and complications" and "Post-endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) septic complications" and "Post-endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis" and "Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography".)

Endoscopic ultrasound EUS can demonstrate extrahepatic biliary cysts, provide detailed images of the cyst

wall and pancreaticobiliary junction, and look for evidence of biliary obstruction. Unlike transabdominal

ultrasonography, EUS is not limited by body habitus, bowel gas, or overlying structures. If there is a mass visualized

within the cyst, it may be sampled by intraductal biopsy obtained during ERCP or cholangioscopy (See "Pathology of

malignant liver tumors", section on 'Cholangiocarcinoma'.).

Intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) has been used for the diagnosis of early malignant changes in a biliary cyst [65]. This

technique is likely to be more sensitive than direct cholangiography for detecting early malignancy in the cyst wall.

(See "Intraductal ultrasound of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system", section on 'Cholangiocarcinoma' and "Clinical

manifestations and diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma", section on 'Endoscopic ultrasound'.)

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

7 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy Hepatobiliary scintigraphy can demonstrate continuity of cysts with the bile ducts.

This nuclear medicine examination uses a radiolabeled bile salt (technetium-99m-labeled hepatic iminodiacetic acid

[HIDA]), which is injected intravenously and is then selectively taken up by hepatocytes and excreted into the bile. In

patients with extrahepatic biliary cysts, the characteristic appearance is of an ovoid or spherical photon-deficient

area that shows progressive radiotracer accumulation on delayed imaging (>2 hours after injection), with persistent

pooling of activity seen for up to 24 hours [66]. This appearance is seen in over 80 percent of extrahepatic biliary

cysts. HIDA scanning may also be useful in cases of cyst rupture since excreted contrast may be seen within the

peritoneal cavity in these patients [67]. (See "Acute cholecystitis: Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis",

section on 'Cholescintigraphy (HIDA scan)'.)

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Biliary cysts should be differentiated from cysts that do not communicate with the

biliary tree including pancreatic, mesenteric, and hepatic cysts. If doubt remains after cross-sectional imaging

(computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography [MRCP]), hepatobiliary scintigraphy

or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can be performed to confirm that the cyst

communicates with the biliary tree. (See 'Hepatobiliary scintigraphy' above and 'ERCP and other forms of direct

cholangiography' above.)

Acute or chronic biliary obstruction may cause marked biliary dilation that mimics a type I cyst. Such patients usually

present with jaundice or elevated serum liver tests, have a readily identifiable obstructing lesion such as a stone,

stricture, or mass, and their biliary dilation often improves after appropriate treatment [68]. A careful evaluation for an

abnormal pancreatobiliary junction (eg, with ERCP) may help with diagnosis in indeterminate cases. (See 'ERCP

and other forms of direct cholangiography' above.)

MANAGEMENT The approach to management of patients with biliary cysts depends on the cyst type. Patients

with type I, II, or IV cysts usually undergo surgical resection of the cysts due to the significant risk of malignancy,

provided they are good surgical candidates. Type I and IV cysts should be completely resected with creation of a

Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy. Serial sections from the cyst wall should be examined by the pathologist to look for

any malignant changes. Type II cysts can be treated with simple cyst excision. Type III cysts (choledochoceles)

require treatment if they are symptomatic and may be managed with sphincterotomy or endoscopic resection [11].

Treatment for type V cysts is largely supportive and is aimed at dealing with problems such as recurrent cholangitis

and sepsis. Type V cysts can be difficult to manage, and some patients with type V cysts eventually require liver

transplantation.

Regardless of the type of cyst, patients with ascending cholangitis require treatment with antibiotics and drainage.

Drainage of an obstructed and infected bile duct can usually be obtained via endoscopic stent placement,

endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. (See "Acute cholangitis", section on

'Management' and "Endoscopic management of bile duct stones: Standard techniques and mechanical lithotripsy"

and "Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography".)

Type I and IV cysts Complete surgical excision is recommended for type I and IV biliary cysts, with the goal of

removing all of the cyst tissue when possible [23]. The approach is advocated because of the risk of malignancy

associated with these cysts. In addition to decreasing the risk of malignancy, cyst excision can reduce complications

such as recurrent cholangitis, cystolithiasis, choledocholithiasis, and pancreatitis.

The lower resection margin depends on the distal extent of the cyst. Various methods have been proposed to

determine the cysts lower border, including [69]:

Preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and/or

ERCP

Intraoperative cholangiography, choledochoscopy, or ultrasonography

Our approach is to assess the distal extent of the cyst and the anatomy of the pancreaticobiliary junction prior to

surgery by MRCP, EUS, and/or ERCP.

Extrahepatic cysts In the case of extrahepatic cysts, resection is usually followed by Roux-en-Y

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

8 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

hepaticojejunostomy to provide biliary drainage from the liver [40,70]. The use of an appendiceal interposition graft

has also been reported in children, but the value of this technique has been questioned [71,72]. In some cases,

excision of the cyst may be complicated by its relationship to nearby structures. If dissection of a cyst from the portal

vein or hepatic artery is technically difficult, some surgeons advocate leaving the posterior cyst wall intact and

performing a mucosectomy (removal of the epithelial lining of the cyst) [40]. The mucosectomy is performed in an

attempt to decrease the risk of malignancy.

The relationship of type I cysts to the pancreatic head can also complicate cyst removal. The intrapancreatic portion

of type I cysts can generally be treated with intramural dissection of the bile duct down to the pancreaticobiliary

junction without pancreatic head resection [73]. If left in place, the intrapancreatic portion of a type I cyst can be

associated with subsequent malignancy or stone formation in the cyst remnant [69].

The most frequent long-term complication of hepaticojejunostomy is stenosis of the biliary-enteric anastomosis

leading to cholangitis, jaundice, or cirrhosis. This complication occurs in up to 25 percent of patients over time

[74,75], and patients should be monitored for evidence of stricture formation with annual serum liver tests.

Intrahepatic cysts Intrahepatic cysts may be difficult to treat. Patients with type IVA cysts often undergo

excision of the cyst with wide hilar Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. However, symptoms may persist due to residual

intrahepatic cysts [76]. Partial hepatectomy is advocated by some surgeons to achieve complete resection of type IV

cysts, particularly in adults [77]. The Roux limb of a hepaticojejunostomy may be sutured to the abdominal wall

(access loop), allowing subsequent percutaneous choledochoscopy via the jejunal limb with stone extractions and

dilations [78]. Surgical unroofing of intrahepatic cysts has also been reported [79]. In some cases liver

transplantation may be required.

Type II cysts In most cases, these cysts can be removed with simple excision [23]. Cysts with complicated

presentations (including jaundice or malignancy in the cyst) may require more extensive resection [80]. (See 'Cyst

type' above.)

Type III cysts Type III cysts require treatment if they are symptomatic. In addition, asymptomatic type III cysts

probably merit treatment in young patients due to the low but real risk of malignancy [11]. Type IIIA cysts are often

amenable to endoscopic sphincterotomy [11]. Because malignancy has rarely been reported in type IIIA cysts,

endoscopic biopsies of the cyst epithelium should be obtained following sphincterotomy to determine if the cyst is

lined by duodenal or biliary mucosa (the latter being associated with an increased risk of malignancy), and to

exclude dysplasia. Endoscopic snare resection of type IIIA cysts can be performed [11]. Type IIIB cysts may be

resected surgically or endoscopically [81,82].

Type V cysts As with type IVA cysts, the intrahepatic cysts in patients with type V biliary cysts can be difficult to

manage. Treatment for type V cysts is largely supportive and is aimed at dealing with problems such as recurrent

cholangitis and sepsis. Some patients with type V cysts will eventually require liver transplantation. The treatment of

patients with type V cysts is discussed elsewhere. (See "Caroli disease", section on 'Treatment'.)

Abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction Patients with an abnormal pancreatobiliary junction (APBJ) and no biliary

cyst should undergo prophylactic cholecystectomy because of the increased risk of gallbladder cancer. (See

"Gallbladder cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features, and diagnosis", section on 'Abnormal

pancreaticobiliary duct junction'.)

Patients with an abnormal pancreatobiliary junction and a dilated common channel may develop proteinaceous

plugs or stones within the common channel, resulting in ductal obstruction and pancreatitis. In such patients, cyst

resection alone may not lead to symptom resolution. Surgical or endoscopic removal of stones or protein plugs from

the common channel and surgical sphincteroplasty or endoscopic sphincterotomy may also be required.

Patients who have undergone cystenterostomy In the past, some patients with type I or IV biliary cysts were

treated with internal drainage via a cystenterostomy. While effective at treating symptoms, the procedure was

associated with significant complications such as ascending cholangitis due to reflux of enteric contents into the cyst

and biliary tree, anastomotic stricture formation, and most importantly, a 30 percent postoperative risk of malignancy

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

9 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

[78,83]. Patients who have previously undergone cystenterostomy should undergo surgery to completely remove the

cyst.

Alternatives to surgery In patients with type I, II, or IV biliary cysts who refuse surgical resection or who are poor

surgical candidates, lesser interventions (such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, endoscopic sphincterotomy, or

endoscopic stent placement) may treat symptoms caused by gallstones or sludge. There is no proven effective

method of screening biliary cysts for dysplasia or intramucosal cancer. If screening is attempted, intraductal

ultrasound (performed via ERCP) is probably the most sensitive test for detecting early malignancy in the cyst wall.

A less invasive approach is to perform periodic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast and MRCP. (See

"Intraductal ultrasound of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system", section on 'Cholangiocarcinoma'.)

PATIENT FOLLOW-UP While the carcinoma risk is decreased in patients who have undergone cyst resection,

these patients continue to be at increased risk of carcinoma in the remaining biliary tree compared with the general

population. Post-excisional malignant disease is seen in 0.7 to 6 percent of patients and may be due to remnant cyst

tissue or subclinical malignant disease that was not detected prior to cyst excision [41,42,75,84,85]. Malignancy may

develop in portions of cysts that were left behind at surgery, at the anastomotic site, or in the pancreas [41,42,86-88].

The appropriate follow-up for patients who have been treated for a biliary cyst is unclear. For those who have

undergone total cyst excision with hepaticojejunostomy, annual serum liver tests are warranted to screen for

anastomotic biliary stenosis. For those who have undergone partial cyst excision or who refuse cyst excision, the

value of periodic imaging tests to screen for malignancy is unproven. It is reasonable to consider yearly imaging

studies (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography with contrast, magnetic resonance

cholangiopancreatography, or intraductal ultrasound) in such patients to assess for early malignant change,

particularly if findings will alter patient management. For those with type III cysts treated with endoscopic

sphincterotomy, it is reasonable to perform endoscopic biopsies of the cyst mucosa, both at the time of

sphincterotomy and a year later, to assess for dysplasia. Patients with malignancy in the resected cyst may require

additional treatment and follow-up. (See "Treatment of localized cholangiocarcinoma: Adjuvant and neoadjuvant

therapy and prognosis".)

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Biliary cysts are cystic dilations that may occur singly or in multiples throughout the biliary tree. Biliary cysts can

lead to significant complications such as ductal strictures, stone formation, cholangitis, secondary biliary

cirrhosis, rupture, and cholangiocarcinoma. (See 'Introduction' above.)

The classification scheme for biliary cysts takes into account cyst location, cyst number, and whether there is

an abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction (figure 1). (See 'Types of biliary cysts' above.)

The classic presentation of a biliary cyst includes the triad of abdominal pain, jaundice, and a palpable mass.

However, the majority of patients will only have one or two elements of the triad. Patients may also report

nausea, vomiting, fever, pruritus, and weight loss. Biliary cysts may also be an incidental finding during prenatal

ultrasonography or in an asymptomatic patient who is undergoing imaging or endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for other reasons. (See 'Clinical manifestations' above.)

Biliary cysts are associated with an increased risk of cancer, particularly cholangiocarcinoma. Overall, the

incidence of cancer is reported to be in the range of 10 to 30 percent, though published reports may

overestimate the true incidence. Cancer is more common in patients who are older and in those with type I and

IV cysts. The risk of cancer is lower in patients with type II or III cysts. Cancer is reported in 7 to 15 percent of

patients with type V cysts. (See 'Cancer risk' above.)

Biliary cysts are typically diagnosed by cross-sectional imaging. Additional testing may be required to rule out

biliary obstruction (ERCP or endoscopic ultrasound) or to confirm communication of the cyst with the biliary

tree (hepatobiliary scintigraphy or ERCP). (See 'Diagnosis' above.)

The management of patients with biliary cysts depends on the cyst type and whether the patient has

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

10 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

symptoms. For cysts with high malignant potential, resection decreases (but does not eliminate) the risk of

malignancy. In addition to decreasing the risk of malignancy, the excision of cysts can reduce complications

such as recurrent cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, and pancreatitis. (See 'Patient follow-up' above.)

For patients with type I or IV cysts, we recommend complete surgical excision of the cyst with Roux-en-Y

hepatojejunostomy rather than expectant management (Grade 1B). Type I and IV cysts have a high risk

of malignancy if left in place. (See 'Type I and IV cysts' above and 'Cancer risk' above and 'Patient

follow-up' above.)

For patients with type II cysts, we suggest simple excision of the cyst rather than expectant management

(Grade 2C). (See 'Type II cysts' above.)

For patients with type III cysts, we suggest treatment of symptomatic cysts as well as asymptomatic cysts

in young patients, rather than treating all patients (Grade 2B). Sphincterotomy is often sufficient to relieve

symptoms but should be accompanied by biopsy of the cyst epithelium to determine if the cyst is lined by

duodenal or biliary mucosa (the latter being associated with an increased risk of malignancy), and to

exclude dysplasia; alternatively, endoscopic or surgical resection may be performed. (See 'Type III cysts'

above.)

Treatment for type V cysts is largely supportive and is aimed at dealing with problems such as recurrent

cholangitis and sepsis. Type V cysts can be difficult to manage, and some patients with type V cysts

eventually require liver transplantation. (See "Caroli disease", section on 'Treatment'.)

For patients with no cyst but an abnormal pancreatobiliary junction, we suggest prophylactic

cholecystectomy rather than expectant management (Grade 2C). Patients with an abnormal

pancreatobiliary junction are at increased risk for gallbladder cancer. (See 'Abnormal pancreaticobiliary

junction' above.)

For those who have undergone total cyst excision, annual serum liver tests are reasonable to screen for

anastomotic biliary stenosis. For those who have undergone partial cyst excision or who refuse cyst excision,

the value of periodic imaging tests to screen for malignancy is unproven. It is reasonable to consider yearly

imaging studies (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography with contrast, magnetic resonance

cholangiopancreatography, or intraductal ultrasound) in such patients to assess for early malignant change,

particularly if findings will alter patient management. For those with type III cysts treated with endoscopic

sphincterotomy, it is reasonable to perform endoscopic biopsies of the cyst mucosa, both at the time of

sphincterotomy and a year later, to assess for dysplasia. Patients with malignancy in the resected cyst may

require additional treatment and follow-up. (See 'Patient follow-up' above.)

Use of UpToDate is subject to the Subscription and License Agreement.

REFERENCES

1. ALONSO-LEJ F, REVER WB Jr, PESSAGNO DJ. Congenital choledochal cyst, with a report of 2, and an

analysis of 94, cases. Int Abstr Surg 1959; 108:1.

2. Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, et al. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and

review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg 1977; 134:263.

3. Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Morotomi Y. Classification of congenital biliary cystic disease: special reference

to type Ic and IVA cysts with primary ductal stricture. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2003; 10:340.

4. Cha SW, Park MS, Kim KW, et al. Choledochal cyst and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union in adults:

radiological spectrum and complications. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2008; 32:17.

5. Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH. Choledochal cysts: part 1 of 3: classification and pathogenesis. Can

J Surg 2009; 52:434.

6. Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, et al. Choledochal cyst disease. A changing pattern of presentation. Ann

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

11 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Surg 1994; 220:644.

7. Kagiyama S, Okazaki K, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto Y. Anatomic variants of choledochocele and manometric

measurements of pressure in the cele and the orifice zone. Am J Gastroenterol 1987; 82:641.

8. Tanaka T. Pathogenesis of choledochocele. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:1140.

9. Sarris GE, Tsang D. Choledochocele: case report, literature review, and a proposed classification. Surgery

1989; 105:408.

10. Scholz FJ, Carrera GF, Larsen CR. The choledochocele: correlation of radiological, clinical and pathological

findings. Radiology 1976; 118:25.

11. Law R, Topazian M. Diagnosis and treatment of choledochoceles. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12:196.

12. O'Neill JA Jr. Choledochal cyst. Curr Probl Surg 1992; 29:361.

13. Hukkinen M, Koivusalo A, Lindahl H, et al. Increasing occurrence of choledochal malformations in children: a

single-center 37-year experience from Finland. Scand J Gastroenterol 2014; 49:1255.

14. Komi N, Takehara H, Kunitomo K, et al. Does the type of anomalous arrangement of pancreaticobiliary ducts

influence the surgery and prognosis of choledochal cyst? J Pediatr Surg 1992; 27:728.

15. Howell CG, Templeton JM, Weiner S, et al. Antenatal diagnosis and early surgery for choledochal cyst. J

Pediatr Surg 1983; 18:387.

16. Han SJ, Hwang EH, Chung KS, et al. Acquired choledochal cyst from anomalous pancreatobiliary duct union.

J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32:1735.

17. Iwata F, Uchida A, Miyaki T, et al. Familial occurrence of congenital bile duct cysts. J Gastroenterol Hepatol

1998; 13:316.

18. Lu, SC. Biliary cysts. In: Textbook of gastroenterology, Yamada, T (Eds), Lippincott Williams and Williams,

Philadelphia 1999. p.2292.

19. Yotuyangi S. Contribution to etiology and pathology of idiopathic cystic dilatation of the common bile duct, with

a report of three cases. Gann (Tokyo) 1936; 30:601.

20. Tyler KL, Sokol RJ, Oberhaus SM, et al. Detection of reovirus RNA in hepatobiliary tissues from patients with

extrahepatic biliary atresia and choledochal cysts. Hepatology 1998; 27:1475.

21. Spitz L. Experimental production of cystic dilatation of the common bile duct in neonatal lambs. J Pediatr Surg

1977; 12:39.

22. Yamao K, Mizutani S, Nakazawa S, et al. Prospective study of the detection of anomalous connections of

pancreatobiliary ducts during routine medical examinations. Hepatogastroenterology 1996; 43:1238.

23. Jaboska B. Biliary cysts: etiology, diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18:4801.

24. Song HK, Kim MH, Myung SJ, et al. Choledochal cyst associated the with anomalous union of

pancreaticobiliary duct (AUPBD) has a more grave clinical course than choledochal cyst alone. Korean J Intern

Med 1999; 14:1.

25. Funabiki T, Matsubara T, Miyakawa S, Ishihara S. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary

and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2009; 394:159.

26. Misra SP, Gulati P, Thorat VK, et al. Pancreaticobiliary ductal union in biliary diseases. An endoscopic

retrograde cholangiopancreatographic study. Gastroenterology 1989; 96:907.

27. Li L, Yamataka A, Yian-Xia W, et al. Ectopic distal location of the papilla of vater in congenital biliary dilatation:

Implications for pathogenesis. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36:1617.

28. Matsumoto S, Tanaka M, Ikeda S, Yoshimoto H. Sphincter of Oddi motor activity in patients with anomalous

pancreaticobiliary junction. Am J Gastroenterol 1991; 86:831.

29. Kato T, Hebiguchi T, Matsuda K, Yoshino H. Action of pancreatic juice on the bile duct: pathogenesis of

congenital choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg 1981; 16:146.

30. Iwai N, Tokiwa K, Tsuto T, et al. Biliary manometry in choledochal cyst with abnormal choledochopancreatico

ductal junction. J Pediatr Surg 1986; 21:873.

31. Craig AG, Chen LD, Saccone GT, et al. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction associated with choledochal cyst. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 16:230.

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

12 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

32. Weyant MJ, Maluccio MA, Bertagnolli MM, Daly JM. Choledochal cysts in adults: a report of two cases and

review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93:2580.

33. Voyles CR, Smadja C, Shands WC, Blumgart LH. Carcinoma in choledochal cysts. Age-related incidence.

Arch Surg 1983; 118:986.

34. Katabi N, Pillarisetty VG, DeMatteo R, Klimstra DS. Choledochal cysts: a clinicopathologic study of 36 cases

with emphasis on the morphologic and the immunohistochemical features of premalignant and malignant

alterations. Hum Pathol 2014; 45:2107.

35. Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH. Choledochal cysts: part 2 of 3: Diagnosis. Can J Surg 2009; 52:506.

36. Shah OJ, Shera AH, Zargar SA, et al. Choledochal cysts in children and adults with contrasting profiles:

11-year experience at a tertiary care center in Kashmir. World J Surg 2009; 33:2403.

37. Singham J, Schaeffer D, Yoshida E, Scudamore C. Choledochal cysts: analysis of disease pattern and optimal

treatment in adult and paediatric patients. HPB (Oxford) 2007; 9:383.

38. Sreide K, Sreide JA. Bile duct cyst as precursor to biliary tract cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14:1200.

39. Lee SE, Jang JY, Lee YJ, et al. Choledochal cyst and associated malignant tumors in adults: a multicenter

survey in South Korea. Arch Surg 2011; 146:1178.

40. Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Urushihara N. Carcinoma related to choledochal cysts with internal drainage

operations. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1987; 164:61.

41. Kobayashi S, Asano T, Yamasaki M, et al. Risk of bile duct carcinogenesis after excision of extrahepatic bile

ducts in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Surgery 1999; 126:939.

42. Watanabe Y, Toki A, Todani T. Bile duct cancer developed after cyst excision for choledochal cyst. J

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 1999; 6:207.

43. Sastry AV, Abbadessa B, Wayne MG, et al. What is the incidence of biliary carcinoma in choledochal cysts,

when do they develop, and how should it affect management? World J Surg 2015; 39:487.

44. Todani T, Tabuchi K, Watanabe Y, Kobayashi T. Carcinoma arising in the wall of congenital bile duct cysts.

Cancer 1979; 44:1134.

45. Ohtsuka T, Inoue K, Ohuchida J, et al. Carcinoma arising in choledochocele. Endoscopy 2001; 33:614.

46. Dayton MT, Longmire WP Jr, Tompkins RK. Caroli's Disease: a premalignant condition? Am J Surg 1983;

145:41.

47. Elnemr A, Ohta T, Kayahara M, et al. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction without bile duct dilatation

in gallbladder cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2001; 48:382.

48. Sugiyama M, Abe N, Tokuhara M, et al. Pancreatic carcinoma associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary

junction. Hepatogastroenterology 2001; 48:1767.

49. Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction without congenital choledochal cyst. Br J Surg

1998; 85:911.

50. Funabiki T, Matsubara T, Ochiai M, et al. Surgical strategy for patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction

without choledocal dilatation. Keio J Med 1997; 46:169.

51. Hidaka E, Yanagisawa A, Seki M, et al. High frequency of K-ras mutations in biliary duct carcinomas of cases

with a long common channel in the papilla of Vater. Cancer Res 2000; 60:522.

52. Kim Y, Hyun JJ, Lee JM, et al. Anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary duct without choledochal cyst: is

cholecystectomy alone sufficient? Langenbecks Arch Surg 2014; 399:1071.

53. Oduyebo I, Law JK, Zaheer A, et al. Choledochal or pancreatic cyst? Role of endoscopic ultrasound as an

adjunct for diagnosis: a case series. Surg Endosc 2015; 29:2832.

54. Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Sanyal AJ. Case 38: Caroli disease and renal tubular ectasia. Radiology 2001;

220:720.

55. Masetti R, Antinori A, Coppola R, et al. Choledochocele: changing trends in diagnosis and management. Surg

Today 1996; 26:281.

56. Akhan O, Demirkazik FB, Ozmen MN, Ariyrek M. Choledochal cysts: ultrasonographic findings and

correlation with other imaging modalities. Abdom Imaging 1994; 19:243.

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

13 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

57. Lam WW, Lam TP, Saing H, et al. MR cholangiography and CT cholangiography of pediatric patients with

choledochal cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999; 173:401.

58. Park DH, Kim MH, Lee SK, et al. Can MRCP replace the diagnostic role of ERCP for patients with choledochal

cysts? Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 62:360.

59. Kim MJ, Han SJ, Yoon CS, et al. Using MR cholangiopancreatography to reveal anomalous pancreaticobiliary

ductal union in infants and children with choledochal cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002; 179:209.

60. Kim SH, Lim JH, Yoon HK, et al. Choledochal cyst: comparison of MR and conventional cholangiography. Clin

Radiol 2000; 55:378.

61. Keil R, Snajdauf J, Rygl M, et al. Diagnostic efficacy of ERCP in cholestatic infants and neonates--a

retrospective study on a large series. Endoscopy 2010; 42:121.

62. Sugiyama M, Haradome H, Takahara T, et al. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction shown on multidetector

CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180:173.

63. Wiedmeyer DA, Stewart ET, Dodds WJ, et al. Choledochal cyst: findings on cholangiopancreatography with

emphasis on ectasia of the common channel. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1989; 153:969.

64. Metreweli C, So NM, Chu WC, Lam WW. Magnetic resonance cholangiography in children. Br J Radiol 2004;

77:1059.

65. Yazumi S, Takahashi R, Tojo M, et al. Intraductal US aids detection of carcinoma in situ in a patient with a

choledochal cyst. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 53:233.

66. Lambie H, Cook AM, Scarsbrook AF, et al. Tc99m-hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scintigraphy in

clinical practice. Clin Radiol 2011; 66:1094.

67. Sood A, Senthilnathan MS, Deswal S, et al. Spontaneous rupture of a choledochal cyst and the role of

hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med 2004; 29:392.

68. Aggarwal S, Kumar A, Roy S, Bandhu S. Massive dilatation of the common bile duct resembling a choledochal

cyst. Trop Gastroenterol 2001; 22:219.

69. Nakano K, Mizuta A, Oohashi S, et al. Protein stone formation in an intrapancreatic remnant cyst after

resection of a choledochal cyst. Pancreas 2003; 26:405.

70. Stain SC, Guthrie CR, Yellin AE, Donovan AJ. Choledochal cyst in the adult. Ann Surg 1995; 222:128.

71. Wei MF, Qi BQ, Xia GL, et al. Use of the appendix to replace the choledochus. Pediatr Surg Int 1998; 13:494.

72. Delarue A, Chappuis JP, Esposito C, et al. Is the appendix graft suitable for routine biliary surgery in children?

J Pediatr Surg 2000; 35:1312.

73. Ando H, Kaneko K, Ito T, et al. Complete excision of the intrapancreatic portion of choledochal cysts. J Am Coll

Surg 1996; 183:317.

74. Rthlin MA, Lpfe M, Schlumpf R, Largiadr F. Long-term results of hepaticojejunostomy for benign lesions of

the bile ducts. Am J Surg 1998; 175:22.

75. Zheng X, Gu W, Xia H, et al. Surgical treatment of type IV-A choledochal cyst in a single institution: children vs.

adults. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 48:2061.

76. Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH. Choledochal cysts. Part 3 of 3: management. Can J Surg 2010;

53:51.

77. Xia HT, Dong JH, Yang T, et al. Extrahepatic cyst excision and partial hepatectomy for Todani type IV-A cysts.

Dig Liver Dis 2014; 46:1025.

78. Saing H, Han H, Chan KL, et al. Early and late results of excision of choledochal cysts. J Pediatr Surg 1997;

32:1563.

79. Yamada T, Furukawa K, Yokoi K, et al. Liver cyst with biliary communication successfully treated with

laparoscopic deroofing: a case report. J Nippon Med Sch 2009; 76:103.

80. Ouassi M, Kianmanesh R, Belghiti J, et al. Todani Type II Congenital Bile Duct Cyst: European Multicenter

Study of the French Surgical Association and Literature Review. Ann Surg 2015; 262:130.

81. Chatila R, Andersen DK, Topazian M. Endoscopic resection of a choledochocele. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;

50:578.

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

14 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

82. Antaki F, Tringali A, Deprez P, et al. A case series of symptomatic intraluminal duodenal duplication cysts:

presentation, endoscopic therapy, and long-term outcome (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 67:163.

83. Tao KS, Lu YG, Wang T, Dou KF. Procedures for congenital choledochal cysts and curative effect analysis in

adults. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2002; 1:442.

84. Ono S, Fumino S, Shimadera S, Iwai N. Long-term outcomes after hepaticojejunostomy for choledochal cyst: a

10- to 27-year follow-up. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45:376.

85. Cho MJ, Hwang S, Lee YJ, et al. Surgical experience of 204 cases of adult choledochal cyst disease over 14

years. World J Surg 2011; 35:1094.

86. Eriguchi N, Aoyagi S, Okuda K, et al. Carcinoma arising in the pancreas 17 years after primary excision of a

choledochal cysts: report of a case. Surg Today 2001; 31:534.

87. Kurokawa Y, Hasuike Y, Tsujinaka T, et al. Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas after excision of a

choledochal cyst. Hepatogastroenterology 2001; 48:578.

88. Tsuchida A, Kasuya K, Endo M, et al. High risk of bile duct carcinogenesis after primary resection of a

congenital biliary dilatation. Oncol Rep 2003; 10:1183.

Topic 651 Version 15.0

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

15 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

GRAPHICS

Classification of biliary cysts according to Todani

and colleagues

(IA) common type; (IB) segmental dilatation; (IC) diffuse dilatation;

(II) diverticulum; (III) choledochocele; (IVA) multiple cysts (intra- and

extrahepatic); (IVB) multiple cysts (extrahepatic); (V) single or multiple

dilatations of the intrahepatic ducts.

From: Savader SJ, Benenati JF, Venbrux AC, et al. Choledochal cysts:

Classification and cholangiographic appearance. Am J Roentgenol 1991;

156:327. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of

Roentgenology.

Graphic 80937 Version 13.0

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

16 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Type I biliary cyst

Image obtained after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

(ERCP) showing a type I biliary cyst associated with an abnormal

pancreaticobiliary junction.

Courtesy of Dr. Morton Burrell.

Graphic 62324 Version 4.0

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

17 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Choledochocele

The upper panels show magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

images of the distal common bile duct with a choledochocele bulging into the

duodenum. The lower images show the corresponding endoscopic views obtained

with forward- (left lower panel) and side-viewing (right lower panel) endoscopes.

The patient is an 85-year-old woman who presented with abdominal pain and

mild, chronic elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase.

Courtesy of Eric D. Libby, MD.

Graphic 81700 Version 2.0

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

18 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrating

an abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction in a child with recurrent

abdominal pain and pancreatitis. Note the long, dilated common channel

(thick arrow) containing a stone (thin arrow). The patient also has

pancreas divisum.

Courtesy of Mark Topazian, MD.

Graphic 77946 Version 5.0

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

19 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in an adult with

obstructive jaundice demonstrates an abnormal pancreaticobiliary

junction with a malignant biliary stricture replacing the cystic duct

insertion. There is no evidence of a biliary cyst.

Courtesy of Mark D Topazian, MD.

Graphic 57937 Version 3.0

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Biliary cysts

20 de 20

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-cysts?topicKey=GAST/651&...

Contributor Disclosures

Mark Topazian, MD Nothing to disclose. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, MACP Nothing to disclose. Elizabeth B Rand, MD

Nothing to disclose. Anne C Travis, MD, MSc, FACG, AGAF Equity Ownership/Stock Options: Proctor & Gamble

[Peptic ulcer disease/GI bleeding (omeprazole)].

Contributor disclosures are reviewed for conflicts of interest by the editorial group. When found, these are addressed

by vetting through a multi-level review process, and through requirements for references to be provided to support

the content. Appropriately referenced content is required of all authors and must conform to UpToDate standards of

evidence.

Conflict of interest policy

31/07/2016 03:24 p. m.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Bisphophonates in CKD Patients With Low Bone Mineral Density PDFDocumento12 páginasBisphophonates in CKD Patients With Low Bone Mineral Density PDFDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Clinical Evidence For Pharmaconutrition in Major Elective Surgery PDFDocumento8 páginasClinical Evidence For Pharmaconutrition in Major Elective Surgery PDFDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Parvovirus Lupus PDFDocumento3 páginasParvovirus Lupus PDFDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Biliary CystsDocumento20 páginasBiliary CystsDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Anxiety, Depression and Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction in HypertensionDocumento5 páginasAnxiety, Depression and Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction in HypertensionDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Parvovirus LupusDocumento3 páginasParvovirus LupusDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Parvovirus b19 ComentaryDocumento2 páginasParvovirus b19 ComentaryDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- FEB - Ca Cu NejmDocumento8 páginasFEB - Ca Cu NejmKARENZITARGAinda não há avaliações

- Parvovirus y Lupus - RelacionDocumento11 páginasParvovirus y Lupus - RelacionDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- Terapia Biologica en Melanoma PDFDocumento8 páginasTerapia Biologica en Melanoma PDFDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Medicina Genomica en Tumores SólidosDocumento12 páginasMedicina Genomica en Tumores SólidosDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Genomica Del CáncerDocumento15 páginasGenomica Del CáncerDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Chest Pain in Acute Coronary SyndromeDocumento86 páginasChest Pain in Acute Coronary SyndromeDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Cancer Genomics and Inherited RiskDocumento13 páginasCancer Genomics and Inherited RiskDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- AdEasy Adenoviral Vector SystemDocumento43 páginasAdEasy Adenoviral Vector SystemDaniel PintoAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- CPR PediatrikDocumento31 páginasCPR PediatrikwenyinriantoAinda não há avaliações

- Liver Cirrhosis Pathophysiology and EvaluationDocumento91 páginasLiver Cirrhosis Pathophysiology and EvaluationGiorgi PopiashviliAinda não há avaliações

- Augmentation Mammoplasty:MastopexyDocumento12 páginasAugmentation Mammoplasty:MastopexyfumblefumbleAinda não há avaliações

- Osteosarcoma CondroblasticoDocumento5 páginasOsteosarcoma CondroblasticoFrancis SortoAinda não há avaliações

- Errors of Refraction PDFDocumento2 páginasErrors of Refraction PDFMichelleAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Anaesthesia 2022 Mcq'sDocumento16 páginasAnaesthesia 2022 Mcq'sMiss IbrahimAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- Breast Diseases BenignDocumento34 páginasBreast Diseases BenignAhmad Uzair QureshiAinda não há avaliações

- Gomez Meda - Esquivel F and SDocumento6 páginasGomez Meda - Esquivel F and SSebastien Melloul100% (1)

- CV For EportfolioDocumento5 páginasCV For Eportfolioapi-301128538Ainda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Case Study Presented by Group 22 BSN 206: In-Depth View On CholecystectomyDocumento46 páginasCase Study Presented by Group 22 BSN 206: In-Depth View On CholecystectomyAjiMary M. DomingoAinda não há avaliações

- Kopkash 2018Documento6 páginasKopkash 2018Yefry Onil Santana MarteAinda não há avaliações

- Transfer To Another Dialysis CenterDocumento2 páginasTransfer To Another Dialysis CenterGeffrey BarceloAinda não há avaliações

- Morisaki 2021Documento4 páginasMorisaki 2021Deborah SalinasAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Maternal First Quiz ReviewerDocumento15 páginasMaternal First Quiz ReviewerRay Ann BorresAinda não há avaliações

- 19 Norma Basalis DR GosaiDocumento24 páginas19 Norma Basalis DR GosaiDr.B.B.GosaiAinda não há avaliações

- Procedure Checklist Chapter 23: Using A Volume-Control Administration Set (E.g., Buretrol, Volutrol, Soluset)Documento2 páginasProcedure Checklist Chapter 23: Using A Volume-Control Administration Set (E.g., Buretrol, Volutrol, Soluset)jthsAinda não há avaliações

- Kit Emergency Perdarahan: Daftar Obat Emergency UgdDocumento6 páginasKit Emergency Perdarahan: Daftar Obat Emergency Ugddyah ajengAinda não há avaliações

- Neck Surgery Anesthesia For Otolaryngology-Head &: Key ConceptsDocumento25 páginasNeck Surgery Anesthesia For Otolaryngology-Head &: Key ConceptsCarolina SidabutarAinda não há avaliações

- College of Veterinary Science & Animal Husbandry MhowDocumento23 páginasCollege of Veterinary Science & Animal Husbandry MhowAkhand PratapAinda não há avaliações

- RAMOS VS CA, 380 SCRA 467: FactsDocumento2 páginasRAMOS VS CA, 380 SCRA 467: FactsEarvin Joseph BaraceAinda não há avaliações

- Ventilation of Health Care Facilities: ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE Addendum L To ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE Standard 170-2017Documento8 páginasVentilation of Health Care Facilities: ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE Addendum L To ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE Standard 170-2017Hamad ElkasehAinda não há avaliações

- Biceps Tendon Tear at The Elbow-Orthoinfo - AaosDocumento5 páginasBiceps Tendon Tear at The Elbow-Orthoinfo - Aaosapi-228773845Ainda não há avaliações

- Pcs Question 1Documento21 páginasPcs Question 1Azra MuzafarAinda não há avaliações

- RPT 54Documento50 páginasRPT 54Leticia LopezAinda não há avaliações

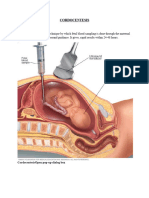

- CORDOCENTESISDocumento6 páginasCORDOCENTESISSagar HanamasagarAinda não há avaliações

- Advanced Paediatric Life Support - A0 PDFDocumento1 páginaAdvanced Paediatric Life Support - A0 PDFiulia-uroAinda não há avaliações

- Skandalakis Surgical Anatomy The EmbryolDocumento2 páginasSkandalakis Surgical Anatomy The EmbryolArvin Aditya PrakosoAinda não há avaliações

- Bio XI NutritionDocumento2 páginasBio XI NutritionAbdul Haseeb JokhioAinda não há avaliações

- Curaplex-EMP Defib Pads Ref Chart 01 19Documento1 páginaCuraplex-EMP Defib Pads Ref Chart 01 19Vikki LeonardiAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomy of The Reproductive System EDocumento4 páginasAnatomy of The Reproductive System EshreeAinda não há avaliações

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNo EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (402)