Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Introduction To Experimental Archaeology

Enviado por

SpyrAlysTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Introduction To Experimental Archaeology

Enviado por

SpyrAlysDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Introduction to experimental

archaeology

Alan K. Outram

What is experimental archaeology?

If one takes a scientic and positivist view (Popper 1959), then experimentation is part of

a hypothetico-deductive process. A hypothesis is formulated and then tested to see if it

can be falsied. If falsied then that hypothesis must be discarded and replaced with a

new, hopefully better one, which will, itself, then be tested. If a hypothesis resists

falsication, and is supported by experimentation, it can be regarded as valid. Valid, in

this sense, does not mean true, but merely that the principles behind the hypothesis can

continue to be used until falsied and replaced by a better set of principles. An

experimental, positivist approach can escape the shackles of simple historicism and

empiricism, because it allows one to move beyond the limited range of options made

available by records of the currently known world. It allows investigation of the counterintuitive and for the possibility of deductive leaps, rather than simply relying upon

probabilistic and inductive extrapolations of existing knowledge.

Positivism is still the underlying philosophy of modern science. While Kuhn (1962) very

clearly outlined his view of how science really works in the fallible and often prejudiced

world of human scientists, his critique was not so much a direct challenge to Poppers

ideals, but more of a reality check. Experimentation remains a method that clearly sits

within the realms of science. The postmodernist attack on science and method (e.g.

Feyerabend 1975) presented instead a philosophy of anything goes, and gave no special

place to testing hypotheses though experimentation. This is not the place to debate, in

depth, the nature of the postmodern or post-processual challenge to science, but the reader

should note that this volume presents experimental archaeology as a scientic research

method. As such, while it is accepted that other theoretical viewpoints will interpret the

experiences of experimenters dierently, this volume does not take an anything goes

approach to the topic, but it does investigate a range of styles and approaches to

experimental archaeology as science.

Having put forward a denition of experimentation, however, it is still not entirely clear

what experimental archaeology exactly means. If experiment is the mainstay of modern

science, then, strictly speaking, is there really any dierence between experimental

archaeology and archaeological science? Readers of key works dating to when the term

experimental archaeology was rst coming into common parlance (e.g. Coles 1973, 1979;

World Archaeology Vol. 40(1): 16 Experimental Archaeology

2008 Taylor & Francis ISSN 0043-8243 print/1470-1375 online

DOI: 10.1080/00438240801889456

Alan K. Outram

Reynolds 1979) will clearly note that it relates only to certain types of activities. Coles

states that the aim of experimental archaeology is to reproduce former conditions and

circumstances (1979: 1), and the same is echoed by Mathieu (2002: 1), who says it is

designed to replicate past phenomena. Indeed, most people, when thinking of

experimental archaeology, are conjuring with words like reconstruction, re-enactment,

reproduction and replication, because the activities of those who engage in the subject

usually seem geared around, in some way, re-creating activities, artefacts, structures and

processes that happened in the past. This concept provides a clear dierence between

experimental archaeology and other forms of archaeological science, but it is perhaps a

defective denition. Reynolds (1999: 159) was very clear about his dislike of the re- prex.

After all, in the vast majority of cases, one does not actually know what the past was like,

so one cannot reconstruct it. Some aspects of an experiment must be hypothetical and

being tested, and, hence, not a reconstruction, otherwise there is little point in doing it.

This is the reason why Reynolds (1999: 159) referred to his hypothetical Iron Age houses

as being constructs. The European journal devoted to experimental archaeology nods its

head at this distinction in its title, while still acknowledging common parlance: EuroRAE:

(Re)construction and Experiment in Archaeology.

Perhaps a more useful term to use is actualistic. To present an example, one can

experimentally study the rendering of tar from birch bark, a material we know was used in

the past (Piotrowski 1999). One could test many factors about source materials, rendering

conditions and end products within the controlled conditions of a laboratory, using sterile

glassware and a gas powered heat source. Each experiment could involve holding all but

one variable constant at any one time. The rendering process could be quite well

understood, in physical terms, from such experiments and some conclusions might be

reached that were relevant to archaeological interpretation. However, a gulf is left between

such laboratory work and how such processes may have been achieved in the past, with a

limited range of materials, technologies and a lesser control upon the environment.

Experimental archaeology comes into its own at this point. What has been learned in the

lab can now be taken further; hypotheses can be tested with authentic materials and in a

range of environmental conditions that aim to reect more accurately real life or

actualistic scenarios. Such experiments investigate activities that might have happened in

the past using the methods and materials that would actually have been available. This is

not to say that all materials and methods need to be authentic in experimental

archaeology, but certainly those pertinent to the hypothesis.

The above two approaches to scientic investigation of past activity should not be seen

as in any way rivals. It is not an either/or situation. These two approaches naturally follow

on from, and complement, each other. Laboratory experiments provide a sound

understanding of scientic principles through the careful control of variables, while

actualistic experiments test out hypothetical scenarios using potentially authentic

materials and conditions. In the latter case, unpredictable phenomena are often given

more opportunity to act, thus enabling the renement of hypotheses and archaeological

interpretation. Experimental archaeology should certainly be viewed as being in no way

separate from the rest of archaeological science. It simply represents a particular type of

experimentation that, in some cases, requires the application of skills or materials not

commonly available in our modern world. Actualistic experiments should be no less

Introduction to experimental archaeology

rigorous than laboratory ones, but that rigour may be based upon a dierent set of

criteria. Maintaining rigour in actualistic scenarios is no mean feat.

Reynolds (1999: 15862) dened ve major classes of experiments that are the mainstay

of experimental archaeology. It is worth briey summarizing them here:

1. Construct: 1:1 scale constructions that test a hypothetical design for a structure (e.g.

house) based upon archaeological evidence. It is a hypothesis that literally stands or

falls.

2. Processes and function experiments: investigations into how things were achieved in

the past. This includes investigations into what tools were for, how they were used

and how other technological processes (e.g. tar rendering or pit storage) were

achieved.

3. Simulation: experimental investigations into formation processes of the archaeological record and post-depositional taphonomy.

4. Eventuality trial: usually combining all three categories above, these are large-scale,

often longue duree, experiments that can investigate complex systems (such as

agriculture) and chart variations caused by unexpected or rare eventualities (e.g.

extreme weather).

5. Technological innovation: where archaeological techniques themselves are trialled in

realistic scenarios. A good example would be the testing of geophysical equipment

over a simulated, buried archaeological site.

What experimental archaeology is not

There is little doubt that the term experimental archaeology is closely associated in many

peoples minds with re-enactment groups, outdoor education and public presentation

centres, and other demonstrations of past life and technology. The journal EuroREA

certainly covers all these aspects. Reynolds made his view, that these activities are not part

of experimental archaeology, bluntly and acerbically clear. The activities of re-enactors

dressed in period costume were, to him, at best theatre, at worst the satisfaction of

character deciencies (1999: 156). Indeed, such activities are clearly not, in philosophical

and research terms, experiments. It is perhaps unfortunate that the boundaries between

experimental archaeology (a research tool), experiences and demonstrations (educational

and presentational tools) and re-enactment activities (a recreational pursuit) have become

blurred in the minds of many. In some cases, one fears that this has coloured academic

perception of a valuable approach to research. Perhaps this is why Reynolds put forward

such a strong rejection of anything not truly experimental.

Of course, real-life demonstrations, three-dimensional (re)constructions and rst-hand

experiences all have huge pedagogical benets and are an excellent way to translate

archaeological research into a presentable form for the public. There is also no need to

deny re-enactors their fun. Furthermore, most true experimenters need to gain a degree of

competence through experience before conducting their experiments (e.g. those who

conduct int-knapping experiments). However, from an academic point of view, it is

clearly benecial to maintain a clear distinction between what is experimental and what is

Alan K. Outram

experiential. Experiential activities can be very valuable and can be easily associated with

an experiment to add a public or educational (translational) element, but that potentially

positive by-product should not be allowed to create confusion over experimental aims.

This volume deals only with experiments for the purpose of research, but this editor has no

wish to do down other valuable activities.

Publishing experimental archaeology: pitfalls and how to avoid them

Through editing this volume, reviewing for many others and teaching experimental

archaeology to graduate students, this editor has noted ve major pitfalls that potential

authors of experimental publications regularly succumb to. Below, these are outlined

along with a discussion about how best to avoid such diculties.

1. Lack of clear aims One of the most frequently encountered problems with

experimental articles is the lack of a well-thought-out hypothesis or a specic

archaeological question that is being addressed. It is likely that the authors are, in

fact, simply writing up a practical, experiential activity, after the fact. The content

may be interesting to like-minded specialists, but, in many cases, the decisions

relating to materials and recording methods would be very arbitrary because of the

lack of a clear aim. This may limit the usefulness of the activity somewhat. Such

experiential reports are not without value, however, and are frequently found

published in journals like EuroREA (in Europe) and the Bulletin of Primitive

Technology (in America). Such works are less likely to be accepted in more

academic publications.

2. Insucient detail on materials and methods If a paper does not outline enough

information about materials and methods then it seriously limits its usefulness, as

other researchers will be unclear what exactly has been tested, and they will not be

able to replicate those experiments or build upon them. EuroREA, recognizing both

of the above common aws, through feedback from its editorial board, has

attempted to encourage its contributors to move towards a more scientic mode of

publication by printing a number of papers on producing good experimental

reports (Mathieu 2005; Outram 2005; Schmidt 2005).

3. Compromises over authentic materials Most experimenters will face dicult

decisions over when to compromise by using more readily available modern

materials (and methods) instead of using rare or totally unavailable authentic ones.

The key question is whether the compromise will materially aect the testing of the

hypothesis. To illustrate, it is unlikely to matter that one pours iron ore into a

smelting experiment from a plastic bucket, but the use of a modern high-grade ore,

not available in the past, could fundamentally defeat the purpose of the experiment.

An experiment that contains too many compromises risks losing any real value. A

compromised actualistic experiment neither has the control of the laboratory nor

does it test the authentic scenario it was designed to.

4. Inappropriate parameters This editor has seen a number of experiments that were

carried out apparently very well with authentic materials, but the basic parameters

Introduction to experimental archaeology

were very badly set to answer the question being asked. Examples of this might be

that the timing of recording points was spaced too far apart or that the starting

temperature was too high. This is suggestive of a lack of experience that could be

addressed through collaboration with experienced craftspeople or technologists, or

through carrying out pilot studies rst.

5. Lack of academic context Very able and experienced practitioners of ancient crafts

have much to oer experimental archaeology, but a problem that aects some

papers submitted by such individuals is a lack of academic context and appropriate

reference to the literature. This signicantly weakens the work.

The last two points are perhaps best addressed through good collaborations between

craftspeople and academics.

Perhaps the most eective experiments are those that are totally integrated into a larger

scheme of academic research with the experimentation being just one of the methods being

employed in pursuit of a research goal. Where possible, there should be close collaboration

between dierent specialists and those with academic and practical skills. If all these

elements are present, then it seems far less likely that any of the above ve mistakes will be

made.

In this volume

The papers in this volume address experiments relating to wide range of dierent

artefactual or ecofactual materials. These include phytoliths (Mithen et al.), bone (Seetah;

Dom nguez-Rodrigo), stone (Aubrey et al.), pottery (Jera), metal (Molloy), organic

materials (Hurcombe) and residues (Evershed). Most of the papers deal with, on some

level, process and function experiments. Two which t very clearly in that category are

Jeras study into the possible use of hair as an organic temper in pottery and Molloys

investigation of the functionality of Bronze Age weapons. However, these two have very

dierent approaches. Jeras paper takes a very quantitative approach, whereas Molloys

work is qualitative. Molloys work is experimental, because he is addressing hypotheses

about the use of particular weapon designs, but his tests rely on qualitative observations

from an experienced martial artist (himself). This opens up an interesting line of debate.

Various quantitative measures about weapons and the damage they inict could be

recorded, but this does not go very far in evaluating their actual use as a weapon. Rather

than putting these too extremes in opposition to each other, perhaps it is best to

acknowledge the value in both types of investigation, while understanding their respective

limitations.

Molloys paper is not the only one that relies heavily upon experienced practitioners.

Aubrey et al. make use of a large number of very experienced int knappers in order to try

to interpret the spectacular lithic assemblage from Maitreaux, France. This assemblage

represents a Solutrean knapping oor (apparently in situ) which was recovered with

amazing spatial resolution. Much retting work has been carried out, and the experiments

are designed to understand the chane operatoire in the reduction sequences and potentially

identify the activities of individual knappers.

Alan K. Outram

Both Dom nguez-Rodrigo and Seetah are concerned with bone surface modications.

The former concentrates on the identication of cut marks, while the latter investigates

wider patterning created by butchery practices. Both investigate in detail the relationship

between experimental work and analogy. They are interesting companion pieces.

Hurcombes paper is a broad-ranging one that demonstrates how experiments,

combined with the analysis of inorganic nds, can shed light upon the use of perishable

organic materials. Organics almost certainly formed a huge proportion of the material

culture of prehistoric peoples, as glimpsed when preservation is exceptional, but,

otherwise, it is necessary to be inventive and develop new ways to enlarge our

understanding by proxy. Another way to understand organic products is through residue

analysis. Evershed shows how actualistic experiments have been used to help understand

the results from analysing lipid residues from ceramics. In this work there are elements of

both process and function and simulation experiments, but this is also an example of

Reynolds (1999) fth class of work, technological innovation, where the experiments

support the development of new techniques of archaeological investigation. Mithen et al.

are also using experiments to help underpin new methodologies, in this case in the eld of

phytolith analysis, but, as with any agricultural trial with multiple plots and a degree of

time depth, this also represents an eventuality trial.

It is hoped that this volume demonstrates the value of actualistic experimentation within

archaeological science, and how such experiments can be integrated into much broader

programmes of research.

Department of Archaeology, University of Exeter

References

Coles, J. 1973. Archaeology by Experiment. London: Hutchinson.

Coles, J. 1979. Experimental Archaeology. London: Academic Press.

Feyerabend, P. 1975. Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge. London:

NLB.

Kuhn, T. S. 1962. The Structure of Scientic Revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mathieu, J. R. 2002. Introduction. In Experimental Archaeology: Replicating Past Objects,

Behaviours and Processes (ed. J. R. Mathieu). Oxford: BAR International Series 1035, Archaeopress,

pp. 14.

Mathieu, J. R. 2005. For the readers sake: publishing experimental archaeology. EuroRAE, 2: 110.

Outram, A. K. 2005. Publishing archaeological experiments: a quick guide for the uninitiated.

EuroREA, 2: 1079.

Piotrowski, W. 1999. Wood-tar and pitch experiments at Biskupin Museum. In Experiment and Design:

Archaeological Studies in Honour of John Coles (ed. A. F. Harding). Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 14855.

Popper, K. 1959. The Logic of Scientic Discovery. London: Hutchinson.

Reynolds, P. J. 1979. Iron-Age Farm: The Butser Experiment. London: British Museum.

Reynolds, P. J. 1999. The nature of experiment in archaeology. In Experiment and Design:

Archaeological Studies in Honour of John Coles (ed. A. F. Harding). Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 15662.

Schmidt, M. 2005. Remarks to the publication of archaeological experiments. EuroREA, 2: 11213.

Você também pode gostar

- Alan Sokal Lecture 2008Documento25 páginasAlan Sokal Lecture 2008psjcostaAinda não há avaliações

- Greek Colonisation An Accountof Greek Coloniesand Other Settlements Overseas Volume 2Documento585 páginasGreek Colonisation An Accountof Greek Coloniesand Other Settlements Overseas Volume 2adeligia100% (6)

- (Religion and Postmodernism) Robert P. Scharlemann - The Reason of Following - Christology and The Ecstatic I-University of Chicago Press (1992) PDFDocumento226 páginas(Religion and Postmodernism) Robert P. Scharlemann - The Reason of Following - Christology and The Ecstatic I-University of Chicago Press (1992) PDFSpyrAlys100% (1)

- Thought ExperimentDocumento42 páginasThought Experimentusman zaheerAinda não há avaliações

- (Mowbray Lent book) Jesus Christ_ Bosch, Hieronymus_ Lewis-Anthony, Justin-Circles of thorns _ Hieronymus Bosch and being human-Bloomsbury Academic_Andrew Mowbray Incorporated, Publishers_Continuum (2.pdfDocumento198 páginas(Mowbray Lent book) Jesus Christ_ Bosch, Hieronymus_ Lewis-Anthony, Justin-Circles of thorns _ Hieronymus Bosch and being human-Bloomsbury Academic_Andrew Mowbray Incorporated, Publishers_Continuum (2.pdfDavi Tomm100% (1)

- Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs For Generalized Causal Inference PDFDocumento81 páginasExperimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs For Generalized Causal Inference PDFGonçalo SampaioAinda não há avaliações

- Ernan McMullin - Conceptions of Science in The Scientific RevolutionDocumento34 páginasErnan McMullin - Conceptions of Science in The Scientific RevolutionMark CohenAinda não há avaliações

- Acta Archaeologica Vol. 72:1, 2001, Pp. 1-150 Printed in Denmark ¡ All Rights ReservedDocumento149 páginasActa Archaeologica Vol. 72:1, 2001, Pp. 1-150 Printed in Denmark ¡ All Rights ReservedmarielamartAinda não há avaliações

- Paul Feyerabend - Outline of An Anarchistic Theory of KnowledgeDocumento8 páginasPaul Feyerabend - Outline of An Anarchistic Theory of KnowledgeJakob AndradeAinda não há avaliações

- Quantum Leaps in The Wrong Direction - Where Descriptions of 'Real Science' EndDocumento5 páginasQuantum Leaps in The Wrong Direction - Where Descriptions of 'Real Science' End50_BMGAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient and Historic MetalsDocumento317 páginasAncient and Historic MetalsSpyrAlys100% (1)

- Beautiful Experiments: An Illustrated History of Experimental ScienceNo EverandBeautiful Experiments: An Illustrated History of Experimental ScienceAinda não há avaliações

- Aar604 Lecture 3Documento55 páginasAar604 Lecture 3Azizul100% (1)

- Review Article: Keywords: Epistemology, Historicity, Experimental Systems, Science As PracticeDocumento24 páginasReview Article: Keywords: Epistemology, Historicity, Experimental Systems, Science As PracticeKarl AlbaisAinda não há avaliações

- Deutz Common RailDocumento20 páginasDeutz Common RailAminadav100% (3)

- HARRISON 1993 - The Soviet Economy and Relations With The United States and Britain, 1941-45Documento49 páginasHARRISON 1993 - The Soviet Economy and Relations With The United States and Britain, 1941-45Floripondio19Ainda não há avaliações

- Easy Pork Schnitzel: With Apple Parmesan Salad & Smokey AioliDocumento2 páginasEasy Pork Schnitzel: With Apple Parmesan Salad & Smokey Aioliclarkpd6Ainda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Experimental Archaeology - Outram PDFDocumento7 páginasIntroduction To Experimental Archaeology - Outram PDFDasRakeshKumarDasAinda não há avaliações

- Outram 2008 Introduction To Experimental ArchaeologyDocumento6 páginasOutram 2008 Introduction To Experimental ArchaeologyAlejandro FernandezAinda não há avaliações

- The Discovery of The Zeeman Effect: A Case Study of The Interplay Between Theory and ExperimentDocumento24 páginasThe Discovery of The Zeeman Effect: A Case Study of The Interplay Between Theory and ExperimentAtilano jose Cubas aranaAinda não há avaliações

- The British Society For The Philosophy of ScienceDocumento14 páginasThe British Society For The Philosophy of ScienceDeznan BogdanAinda não há avaliações

- Experiment As InterventionDocumento13 páginasExperiment As InterventionMaría Cristina Cifuentes ArcilaAinda não há avaliações

- Experiencing Archaeology by Experiment: Penny Cunningham, Julia Heeb and Roeland PaardekooperDocumento10 páginasExperiencing Archaeology by Experiment: Penny Cunningham, Julia Heeb and Roeland PaardekooperEmilyAinda não há avaliações

- Stages On The Empirical Program of RelativismDocumento9 páginasStages On The Empirical Program of RelativismJorge Castillo-SepúlvedaAinda não há avaliações

- Inference, Explanation, and Other Frustrations: Essays in the Philosophy of ScienceNo EverandInference, Explanation, and Other Frustrations: Essays in the Philosophy of ScienceAinda não há avaliações

- C Leland 2002Documento24 páginasC Leland 2002jbaenaAinda não há avaliações

- Arqueologia Experimental 345345Documento7 páginasArqueologia Experimental 345345Silvia ReginaAinda não há avaliações

- Designing Experimental Research in ArchaeologyDocumento3 páginasDesigning Experimental Research in Archaeologyarkea88Ainda não há avaliações

- HEERING, P. - Tools For Investigation, Tools For InstructionDocumento9 páginasHEERING, P. - Tools For Investigation, Tools For InstructionDouglas DanielAinda não há avaliações

- 0401 0101F2-Scientific MethodDocumento4 páginas0401 0101F2-Scientific MethodLileng LeeAinda não há avaliações

- 1887 - 2718709-Article - Letter To EditorDocumento18 páginas1887 - 2718709-Article - Letter To EditorCesar MullerAinda não há avaliações

- The Scientific Nature of Post ProcessulismDocumento21 páginasThe Scientific Nature of Post ProcessulismBillwadal BhattacharjeeAinda não há avaliações

- The Ancient Maya and The Political PreseDocumento21 páginasThe Ancient Maya and The Political Presepedroponce997Ainda não há avaliações

- Cientific InvestigationDocumento35 páginasCientific InvestigationJorge Eduardo Escareño MoralesAinda não há avaliações

- Do The Social Sciences Create Phenomena?: The Example of Public Opinion ResearchDocumento30 páginasDo The Social Sciences Create Phenomena?: The Example of Public Opinion ResearchLeland StanfordAinda não há avaliações

- SKI TerjemahanDocumento5 páginasSKI TerjemahanDania PramestiAinda não há avaliações

- Johnson Et Al 2006Documento66 páginasJohnson Et Al 2006AsbelAinda não há avaliações

- Batley 2007Documento51 páginasBatley 2007Cesar AstuhuamanAinda não há avaliações

- Situating Technoscience: An Inquiry Into Spatialities: J.law@lancaster - Ac.ukDocumento13 páginasSituating Technoscience: An Inquiry Into Spatialities: J.law@lancaster - Ac.ukRepositorioAinda não há avaliações

- Shaddish ExperimentalDocumento81 páginasShaddish ExperimentaldaraAinda não há avaliações

- Science TechDocumento121 páginasScience TechJulius CagampangAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy of Science Research Paper TopicsDocumento8 páginasPhilosophy of Science Research Paper Topicsfyt18efe100% (1)

- Dawes - Experimental Versus Speculative Natural Philosophy: The Case of GalileoDocumento20 páginasDawes - Experimental Versus Speculative Natural Philosophy: The Case of GalileolibrekaAinda não há avaliações

- Paradigms in Science and ArcheologyDocumento34 páginasParadigms in Science and ArcheologyartaAinda não há avaliações

- Lab EthnographyDocumento22 páginasLab EthnographyMelina StrongAinda não há avaliações

- Heinz Otto SibumDocumento34 páginasHeinz Otto SibumzutemdodpcbndAinda não há avaliações

- On The Fundamental Tests of The Special Theory of RelativityDocumento15 páginasOn The Fundamental Tests of The Special Theory of RelativityAndre LanzerAinda não há avaliações

- Experiments With Interactional Expertise - Harry Collins, Rob Evans, Rodrigo Ribeiro, Martin Hall 2006Documento19 páginasExperiments With Interactional Expertise - Harry Collins, Rob Evans, Rodrigo Ribeiro, Martin Hall 2006Ali QuisAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Science and Why Should We Care?Documento25 páginasWhat Is Science and Why Should We Care?guianeyav3770Ainda não há avaliações

- American Anthropologist - April 1954 - HAWKES - Archeological Theory and Method Some Suggestions From The Old WorldDocumento14 páginasAmerican Anthropologist - April 1954 - HAWKES - Archeological Theory and Method Some Suggestions From The Old WorldFaizan Rashid LoneAinda não há avaliações

- The Methods of ScienceDocumento34 páginasThe Methods of ScienceTasia DeastutiAinda não há avaliações

- Ascher Analogy 1961Documento10 páginasAscher Analogy 1961Francois G. RichardAinda não há avaliações

- The Chicken and Egg, RevisitedDocumento14 páginasThe Chicken and Egg, RevisitedC.J. SentellAinda não há avaliações

- Middle-Range Theory in Historical ArchaeologyDocumento22 páginasMiddle-Range Theory in Historical ArchaeologyAli JarkhiAinda não há avaliações

- TBM L2 PDFDocumento8 páginasTBM L2 PDFaaroncete14Ainda não há avaliações

- 2 PaulCockburnDocumento7 páginas2 PaulCockburnGonçalo JustoAinda não há avaliações

- University of Pennsylvania PressDocumento33 páginasUniversity of Pennsylvania PressKrck PhuAinda não há avaliações

- How Interdisciplinary Is Interdisciplinarity. Revisiting theimpactofaDNAresearchforthearchaeologyofhumanremainsDocumento22 páginasHow Interdisciplinary Is Interdisciplinarity. Revisiting theimpactofaDNAresearchforthearchaeologyofhumanremainsMonika MilosavljevicAinda não há avaliações

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Thomas S. Kuhn, 1970, 2 Ed. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press Ltd. 210 Pages)Documento8 páginasThe Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Thomas S. Kuhn, 1970, 2 Ed. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press Ltd. 210 Pages)radge edgarAinda não há avaliações

- Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science: A Historical Ontology byDocumento11 páginasMaterials in Eighteenth-Century Science: A Historical Ontology byMegegAinda não há avaliações

- Ascher 1961 - Analogy in Archaeological InterpretationDocumento10 páginasAscher 1961 - Analogy in Archaeological Interpretationpharetima100% (1)

- Allotropes of Fieldwork in NanotechnologyDocumento35 páginasAllotropes of Fieldwork in NanotechnologyaptureincAinda não há avaliações

- GALISON Philosophy in The Laboratory PDFDocumento4 páginasGALISON Philosophy in The Laboratory PDFNALLIVIAinda não há avaliações

- Hans Radder - The Material Realization of ScienceDocumento211 páginasHans Radder - The Material Realization of ScienceJohanSaxarebaAinda não há avaliações

- L. Zinda, Introduction To The Philosophy of Science PDFDocumento73 páginasL. Zinda, Introduction To The Philosophy of Science PDFlion clarenceAinda não há avaliações

- 4 Scientific Process 060708Documento41 páginas4 Scientific Process 060708Ridwan EfendiAinda não há avaliações

- Anne-Françoise, Choisir Dionysos. Les Associations Dionysiaques Ou La Face Cachée Du DionysismeDocumento4 páginasAnne-Françoise, Choisir Dionysos. Les Associations Dionysiaques Ou La Face Cachée Du DionysismeSpyrAlysAinda não há avaliações

- Anne-Françoise, Choisir Dionysos. Les Associations Dionysiaques Ou La Face Cachée Du DionysismeDocumento4 páginasAnne-Françoise, Choisir Dionysos. Les Associations Dionysiaques Ou La Face Cachée Du DionysismeSpyrAlysAinda não há avaliações

- μενδDocumento6 páginasμενδSpyrAlysAinda não há avaliações

- Communicating Identity in An Italic-GreeDocumento24 páginasCommunicating Identity in An Italic-GreeSpyrAlysAinda não há avaliações

- Non Medieval LawsDocumento1 páginaNon Medieval LawsSpyrAlysAinda não há avaliações

- New Technologies in The Process of Educating About The Archaeological Heritage PDFDocumento11 páginasNew Technologies in The Process of Educating About The Archaeological Heritage PDFSpyrAlysAinda não há avaliações

- Medieval LawsDocumento1 páginaMedieval LawsSpyrAlysAinda não há avaliações

- Medieval LawsDocumento1 páginaMedieval LawsSpyrAlysAinda não há avaliações

- TRYOUT1Documento8 páginasTRYOUT1Zaenul WafaAinda não há avaliações

- English Unit 7 MarketingDocumento21 páginasEnglish Unit 7 MarketingKobeb EdwardAinda não há avaliações

- In Practice Blood Transfusion in Dogs and Cats1Documento7 páginasIn Practice Blood Transfusion in Dogs and Cats1何元Ainda não há avaliações

- MoMA Learning Design OverviewDocumento28 páginasMoMA Learning Design OverviewPenka VasilevaAinda não há avaliações

- Sokkia GRX3Documento4 páginasSokkia GRX3Muhammad Afran TitoAinda não há avaliações

- Schopenhauer and KantDocumento8 páginasSchopenhauer and KantshawnAinda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento2 páginasUntitledRoger GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Geotech Report, ZHB010Documento17 páginasGeotech Report, ZHB010A.K.M Shafiq MondolAinda não há avaliações

- Co-Publisher AgreementDocumento1 páginaCo-Publisher AgreementMarcinAinda não há avaliações

- Eva Karene Romero (Auth.) - Film and Democracy in Paraguay-Palgrave Macmillan (2016)Documento178 páginasEva Karene Romero (Auth.) - Film and Democracy in Paraguay-Palgrave Macmillan (2016)Gabriel O'HaraAinda não há avaliações

- Simple FTP UploadDocumento10 páginasSimple FTP Uploadagamem1Ainda não há avaliações

- MTE Radionuclear THYROID FK UnandDocumento44 páginasMTE Radionuclear THYROID FK UnandAmriyani OFFICIALAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of Religion in The Causation of Global Conflict & Peace and Other Related Issues Regarding Conflict ResolutionDocumento11 páginasThe Role of Religion in The Causation of Global Conflict & Peace and Other Related Issues Regarding Conflict ResolutionlorenAinda não há avaliações

- How To Play Casino - Card Game RulesDocumento1 páginaHow To Play Casino - Card Game RulesNouka VEAinda não há avaliações

- Goldilocks and The Three BearsDocumento2 páginasGoldilocks and The Three Bearsstepanus delpiAinda não há avaliações

- Provisional DismissalDocumento1 páginaProvisional DismissalMyra CoronadoAinda não há avaliações

- Bacanie 2400 Articole Cu Cod de BareDocumento12 páginasBacanie 2400 Articole Cu Cod de BareGina ManolacheAinda não há avaliações

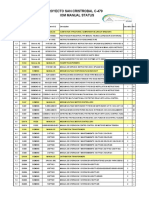

- Proyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusDocumento18 páginasProyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusAllen Marcelo Ballesteros LópezAinda não há avaliações

- 17-05-MAR-037-01 凱銳FCC Part15B v1Documento43 páginas17-05-MAR-037-01 凱銳FCC Part15B v1Nisar AliAinda não há avaliações

- Faculty of Computer Science and Information TechnologyDocumento4 páginasFaculty of Computer Science and Information TechnologyNurafiqah Sherly Binti ZainiAinda não há avaliações

- Roger Dean Kiser Butterflies)Documento4 páginasRoger Dean Kiser Butterflies)joitangAinda não há avaliações

- MMWModule1 - 2023 - 2024Documento76 páginasMMWModule1 - 2023 - 2024Rhemoly MaageAinda não há avaliações

- Ingrid Gross ResumeDocumento3 páginasIngrid Gross Resumeapi-438486704Ainda não há avaliações

- 008 Supply and Delivery of Grocery ItemsDocumento6 páginas008 Supply and Delivery of Grocery Itemsaldrin pabilonaAinda não há avaliações

- 47 Vocabulary Worksheets, Answers at End - Higher GradesDocumento51 páginas47 Vocabulary Worksheets, Answers at End - Higher GradesAya Osman 7KAinda não há avaliações

- AN6001-G16 Optical Line Terminal Equipment Product Overview Version ADocumento74 páginasAN6001-G16 Optical Line Terminal Equipment Product Overview Version AAdriano CostaAinda não há avaliações