Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

2002 Dale Robertson Regional Organizations As Subjects of Globalization Education

Enviado por

Anabela ReisTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

2002 Dale Robertson Regional Organizations As Subjects of Globalization Education

Enviado por

Anabela ReisDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Varying Effects of Regional Organizations

as Subjects of Globalization of Education

ROGER DALE AND SUSAN L. ROBERTSON

Introduction

Globalization is too broad and too ambiguous a term to be used unproblematically in determining the effects on national education systems of

the structures and processes, institutions and practices, that it connotes. Globalization is not a homogeneous force, nor is it consistent in effects on education, either within or between countries. Rather, it is both an extremely

complex process, whose most important feature is that it operates at many

different levels with a range of different effects, and a powerful and far from

monolithic discourse that is employed and called on to justify or denounce

a wide range of changes in contemporary societies. In this article we will

focus on one of the most significant levels at and through which globalization

operates, that of regional organizations, and we will seek to establish how

those organizations affect education within and outside them. We will focus

on the role of the three major regional organizationsthe European Union

(EU), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the Asia

Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). Though they each have as a central

purpose seeking the control and orientation of international trade in their

favor, the regional organizations have themselves become significant agents

in both powering and steering the forces that make up global capitalism.

However, we will argue that while they were set up with that purpose, it is

not possible for their activities and influence to be confined to trade matters.

They necessarily have wider social assumptions and implications. This is especially evident in the area of social infrastructure, particularly for our purposes in the formation of human capital, though the effects are not by any

means confined to that.

We begin the article by raising questions about the nature of globalization

and how we might understand its dynamics. We then turn to an elaboration

of the growth and forms of regional organizations and their role in globalization. In the third section of the article we consider the purpose and form

of the three major regional organizationsEU, NAFTA, and APECand

consider some of their formal statements on education. Finally, we develop

a set of dimensions that enable us to see more clearly how globalization works

through regional organizations and what effects this has on national and

subnational education systems.

Comparative Education Review, vol. 46, no. 1.

2002 by the Comparative and International Education Society. All rights reserved.

0010-4086/2002/4601-0002$05.00

10

Comparative Education Review

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

What Is Globalization?

Globalization is a very complex and confusing term whose meaning

appears to vary and is very difficult to pin down; we have already alluded to

the source of the complexity and confusion in referring to its dual (process

and discourse) meanings. These two sets of meanings are frequently confused, and in our view, it is important to any discussion of globalization,

though sometimes quite difficult, to distinguish between them. In this article,

rather than take up space with an extended discussion of the vast literature

on globalization, we will seek to elaborate briefly on the nature and effects

of globalization as a process. Very broadly, we might say that globalization in

this sense has been associated with analytic approaches, while in the second

sense it has been associated with advocacy, whether pro- or antiglobalization.

An important step in this procedure is to recognize that much of the literature

has essentially treated globalization as a process without a subject.1 This

recognition not only pinpoints a major source of the confusion and apprehension around globalization but also, and of more direct value to this article,

requires us to identify the subjects and drivers of the globalization process

and what that might mean for the globalization of education. A wide range

of such subjects might be acknowledged: transnational corporations, international financial institutions, international organizations, such as the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), but it is

also clear that major regional organizations may be seen as subjects of globalization. Our purpose here, then, is to examine something of the nature

and effect of those organizations in the education sector in ways that reflect

and, we hope, uncover the relationship between globalization and regionalization in education.

This examination requires us to expand a little on what we understand

by globalization, the process. Certainly, it is not an inevitable, irresistible,

ineluctable force over which no one has any control and that we have to put

up with, whatever its implications for us. Rather, globalization represents a

complex, overlapping set of forces, operating differently at different levels,

each of which was separately set in motion intentionally, though their collective outcomes were not uniform, intended, or predicted.

One way that we find it useful to conceptualize the epochal nature of

the changes the term globalization attempts to capture is via a shift from

quantitative to qualitative change, in the way that applying a sufficient quantity of heat to water results in its qualitative change into steam. Myriad major

and minor changes, with common though heterogeneous sources in changing forms of capitalism, arise from the activities of a range of subjects of

globalization and are not reducible to the intentions of any one of them but

1

See Colin Hay, What Place for Ideas in the Structure-Agency Debate? Globalisation as a Process

without a Subject (paper presented at the annual conference of the British International Studies

Association, University of Manchester, December 2022, 1999).

Comparative Education Review

11

DALE AND ROBERTSON

with a shared core aggregated to a point where they formed a clear separation

from previous ways of organizing the economy, politics, and culture at supranational, national, and subnational levels. Though iconic, the collapse of

the Soviet Union and the eastern bloc represented an important shift in the

nature of global relations. This transformed not only politics on a world scale,

and on a national scale, where traditional priorities were disrupted almost

over night, but also the possibilities for capitalist expansion and the penetration of Western values across the world.

This epochal change involved the sweeping away of what were previously

nationally based barriers to the spread of institutions and practices far beyond their local origins. These global processes have not, of course, eliminated all vestiges of the national or the local, nor, as we shall argue in the

body of this article, have they led to convergence between the countries,

or the regions, of the world. Indeed, the core of the issue for us here is

that the forces of globalization do not sweep away all before them and

homogenize everything. At one level this is because the installation of global

processes and practices is not totally determinative in its needs and expectations; on the contrary, it can live alongside a range of existing (national

and local) institutions and combine with them in a range of ways to obtain

the desired ends. More than this, local structures and institutions, processes

and practices, are crucial to, even the medium necessary for, the spread of

global practices.

One useful expression of this idea has been put forward by Jane Jenson

and Boaventura Sousa Santos.2 They argue that while there is a consensual

basis to globalization made up of what they call the neoliberal economic

consensus, the weak state consensus, the liberal democratic consensus, and

the rule of law and judicial consensus (which may be seen as one way of

specifying more closely what we referred to as the common core of the

activities of the main subjects of globalization), there is no single way to

institute any of them locally. They write, In order to diffuse efficiently, processes must be made local. In each case, the general must be given specific

form, specific content.3 In the remainder of this article we will follow Jenson

and Santos in suggesting that though there may be a common thread running

through globalization processes and practices, this does not mean that they

take the same form in all places. And, in particular, we shall be looking here

at the influence and effects of regional organizations in giving specific form

and content to the general, especially in the area of education.

Jane Jenson and Boaventura Sousa Santos, eds., Globalizing Institutions: Case Studies in Regulation

and Innovation (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000).

3

Ibid., p. 21.

12

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

The Growth and Form of Regional Organizations

For at least two fundamental reasons, the idea of a global economy operating in complete isolation from, and above, nation-states is an impossible

one. First, left to the logic of the competitive market alone, capitalism would

not be sustainable; unfettered competition would be ultimately destructive

of the system as a whole. Second, the fetters that it therefore depends on

for sustainability, that would prevent the war of all against all, can only,

certainly currently and for the foreseeable future, be provided by nationstates, one of whose defining characteristics is the ability to make and enforce

laws and regulations within their territory. The kinds of laws and institutional

frameworks such as property rights, contracts, and money, which as Polanyi

and his followers argue constitute the necessary embedding of the capitalist

economy, are still made almost exclusively by, or at least with, the agreement

of nation-states.4 However, one effect of globalization has been to enable

transnational capital in particular to escape from, to evade, or at least to

choose between, the fetters placed upon it through such means as tax havens

and tax breaks from governments eager to provide them with an ultraprofitable base.

Moves to weaken national regulations have, though, a similarly self-destructive potential to that of unfettered capitalism; in this case, they take the

form of a race to the bottom in terms of the legal and fiscal concessions

granted to transnational corporations (TNCs) by national governments. This,

again, is a race that can only produce losers, for there are limits to the

concessions a state can make while remaining viable; moreover, in approaching those limits, states necessarily drag other states behind them. One obvious

solution to this dilemma for states is to erect tariffs and other protective

measures around their own industries and trade. However, these sorts of

measures have been the particular targets and victims of neoliberal orthodoxy

as stimuli and challenges to the expansion of free trade. Nonetheless, this

strategy itself contains no solution to the institutional structure problem; as

Bob Jessop puts it, It is in disrupting past compromises and fixes without

providing a new structured coherence for continued capital accumulation

that neo-liberal forms of globalization appear to be so threatening to many

capitalistlet alone otherinterests.5

Together these dilemmas have created the necessity for constitutionalizing

the neo-liberal, that is to say, setting up what amounts to a minimal regulatory

framework to control the potential excesses of capitalism.6 This takes a number

of forms, all of which are effectively multinational agreements to tame those

4

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation (Boston: Beacon, 1957).

Bob Jessop, Reflections on Globalization and Its (Il)logic(s), in Globalisation and the Asia Pacific:

Contested Territories, ed. Kris Olds, Peter Dicken, Paul F. Kelly, Lily Kong, and Henry Wai-chung Yeung

(London: Routledge, 1999), p. 26.

6

See Leo Panitch, The State and Globalisation, in Socialist Register, ed. R. Miliband and L. Panitch

(London: Merlin, 1994), pp. 6093.

5

Comparative Education Review

13

DALE AND ROBERTSON

excesses and avert the race to the bottom. Saskia Sassen spells out the consequences of this very well when she writes What is conceived of as a line

separating the national from the globalor non nationalis actually a zone

where old institutions are modified, new institutions are created, and there is

much contestation and uncertain outcomes. . . . Globalization in this conception . . . has to do with the relocation of national public governance functions to transnational private arenas and with the development inside national

states . . . of the mechanisms necessary to accommodate the rights of global

capital in what are still national territories.7

Two sets of vehicles for the organization and transmission of the institutions are of special interest, though we should note that their fundamental

purposes do not diverge greatly and that there is considerable overlap in

their membership. The best known by far is the group of international financial, economic, and trade institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), OECD, the World Trade Organization

(WTO), and G7/8. Their precise purposes and forms vary but they all subscribe broadly to Jenson and Santoss four elements of consensus. Although

the forms that these elements take may alter over time (e.g., the particular

form they took in the last decade of the twentieth century, what has been

called the Washington Consensus, appears now to be on the wane), the

significance and role of the international organizations are not affected because their importance derives from their structural position in the global

economy rather than on any particular policy for their influence.8 These

organizations can be seen as composing the kernel of a form of global governance set up by the leading capitalist states to advance the capitalist system

in such ways as to protect their own leading position within it, essentially by

saving the system from itself. In essence they play the role of the collective

capitalist state, meeting the conditions of the existence of capitalism at a

global level that it cannot meet itself. They are able, through conditionality,

loans, debts, and other strategies, to impose the model not only on the leading

nations but on the whole world.

Obviously, though, for the purposes of this article, the most relevant set

of organizations carrying out this role is that of regional organizations.9 We

need to begin by noting that their foundation on a common geographical

basewhich in itself should be seen as constructed rather than naturally

7

Saskia Sassen, Servicing the Global Economy: Reconfigured States and Private Agents, in Olds

et al., eds., p. 159.

8

See John Williamson, Democracy and the Washington Consensus, World Development 21 (1993):

132936; and John Pender, From Structural Adjustment to Comprehensive Development Framework:

Conditionality Transformed, Third World Quarterly 22 (2001): 38196. There are some points made in

Penders article about the increasing importance of social capital development from which we might

infer that regional organizations might be seen as able to perform a different and wider role than under

the Washington Consensus.

9

Daniel Drache lists eight regional free trade agreements; see D. Drache, Trade Blocs: The Beauty

or The Beast in the Theory? in Political Economy and the Changing Global Order, ed. Richard Stubbs and

Geoffrey R. D. Underhill, 2d ed. (Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 18497.

14

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

occurring geographical entities and may even be somewhat shaky geographically, especially in the case of Asian groupingscannot be taken to mean

that they all operate in the same way: though it may be possible to point to

broadly similar aims and purposes, the differences in their modes of organization are much more evident.

In his very useful account of the growth of regionalism, Richard Stubbs

suggests that interest in and the pace of regionalization have accelerated

since the mid-1980s for three fundamental reasonsthe end of the Cold

War, which disrupted the existing pattern of international relations and led

states to form new relationships with each other; provision of both a defense

against and a means for taking advantage of processes of globalization; and

the existence of the EU as both a model and a threat. The emphasis in the

new regionalism has been on positioning the region so as to strengthen its

participation in the global economy in terms of both trade and capital flows.10

This does not mean that regionalization is unproblematic. As Daniel

Drache points out, the primary objectives and problems of regional organizations are access to the world economy and how to improve it, asymmetries

between members and how to neutralize them, and adjustment and how to

pay for it. Together, these mean that a trade bloc . . . needs a strong set of

non-market regulatory institutions to counter market imperfections and

failure.11

There are two major points to be noted here. The main interest in regionalism has been in how far it promotes or acts as a basis for resistance to

the development of the global economy; though these are extremely interesting and relevant issues in themselves, that is not our main concern here.

The first key point at this level is to recognize that regions do not merely

mediate globalization and its effects but that through their activities they

contribute strongly to constructing both. That is to say, if they are the victims

or beneficiaries of the rescaling that regionalization implies, they are also

the more or less willingauthors of it.

This takes us to the second, deceptively obvious point. That is, all the

regional organizations we will be discussing are the deliberate creation of

national governments. This cession of national power (some degree of sovereignty and/or autonomy) to supranational bodies is always justified in terms

of the ultimate good of the national societyor at least, the national economy,

from whose consequent improvement, neoliberal theory tells us, national

society will benefit by means of the trickle-down effect. So, just as in the case

of the international organizations like the World Bank, IMF, and the WTO,

a greater or lesser degree of national sovereignty or autonomy is ceded to

10

Richard Stubbs, Introduction: Regionalisation and Globalization, in Stubbs and Underhill, eds.,

pp. 23134.

11

Drache, p. 184.

Comparative Education Review

15

DALE AND ROBERTSON

regional organizations in order to pursue the national interest more

effectively.

However, our argument is that it is impossible to confine the effects of

regional organization membership on national policy to the trade (or even

the economic) sphere, whether the regional organization would wish that to

be the case or notand it is clear that this is a major point of difference

between them, with the EU quite explicitly involved in such an extension of

its scope while NAFTAs face is seemingly set quite firmly against it. It is to

this element of the issue that we now turn.

The Noneconomic Effects of Regional Organizations

In this section, while registering and recognizing that membership of

international organizations has a range of consequences at national levels,

our main focus will be on the social infrastructural assumptions of regional

organizations; those matters that result from the need for any economic,

productive, or trade force to be embedded in a set of social institutions that

underpin them or are at least not antagonistic to them.

It has become widely acknowledged that globalization has a significant

effect on states policy discretion and that it has led to states changing toward

what has been called a competitive form.12 So, a particular point of this

section is to try to understand the relationship between the competitive state

and regionalization. Bob Jessop has neatly encapsulated the thrust of what

we want to suggest. He argues that there are objective limits to economic

globalization due to capitals need not only to disembed economic relations

from their old social integument but also to re-embed them into new supportive social relations. Indeed, hard economic calculation increasingly rests

on mobilizing soft social resources, which are irreducible to the economic

and resistant to such calculation.13 He also examines two specific new forms

of contradiction and dilemmas that have emerged in the present period of

after Fordist accumulation. The first problem, he suggests,

is evident in the paradox noted by Veltz . . . that [t]he most advanced economies

function more and more in terms of the extra-economic. The paradox rests on

the increasing interdependence between the economic and extra-economic factors

making for systemic competitiveness. For this generates new contradictions that

affect the spatial and temporal organization of accumulation. Thus, temporally,

there is a major contradiction between short-term economic flows and the longterm dynamic of real competition rooted in resources (skills, trust, collective

mastery of techniques, economics of agglomeration, and size) which take years to

create, stabilize, and reproduce. And, spatially, there is a fundamental contradiction

between the economic, considered as a pure space of flows and the economy as a

12

See, e.g., Susan Robertson and Roger Dale, Competitive Contractualism: A New Social Settlement in New Zealand, in World Yearbook of Education: Education in Times of Transition, ed. David Coulby,

Robert Cowen, and Crispin Jones (London: Kogan Page, 2000), pp. 11631.

13

Jessop, p. 37.

16

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

territorially and/or socially embedded system of extra-economic as well as economic

resources and competencies.14

This means that national states must now manage the rearticulation of scales,

where the respective needs of capital and the state are reflected in a variable

mix of institutional forms and governance mechanisms involved in stabilizing

specific economic spaces.15

What is left implicit here is that the major regional groupings vary in the

emphases they place on the extraeconomicthough that is not immediately

evident from the language in which such claims are couched, which is noticeably common across the three regions. Thus, they all refer to the importance of social infrastructure at a regional levelbut they realize that

intention in very different ways.

It is important to register one other point about the nature and consequences of increasing regionalization that has considerable significance for

both the many countries that are still outside regional organizations and for

the leverage that regional organizations are able to exert on those nonmembers. It comes in a paper written for the OECD by a commentator welldisposed toward the nature and outcomes of the joint processes of globalization and regionalization and given to regarding the one as wholly economic

and the other as wholly political; he notes, Globalization and regionalization

constitute a dual challenge for firms and governments in developing countries. Both phenomena are creating opportunities for strengthening NorthSouth integration, and for enhancing productivity growth, competitiveness,

and living standards in developing countries. But, for many countries they

also raise the spectre of involuntary exclusion from the emerging tri-polar

world (our emphasis).16

A related consequence of the recognition of what regional organizations

mean is seen in what we might call the anticipatory effect that regional

organizations have on their potential new members. This is most clearly

evident in what Laux calls the Euroconformity that galvanizes policy-makers

in 10 associated countries [seeking to join the EU] to align along European

standards.17 This includes demonstrating an adequate level of educational

provision (e.g., Portugals entry into the EU in 1986 was made conditional

on such a provision). This capacity for extraregional influence illustrates

another means through which regional organizations act as bearers or carriers

of globalization even to countries that are not members of a regional

organization.

14

Ibid., pp. 2930.

Ibid., pp. 3334.

16

Charles Oman, Globalisation and Regionalisation: The Challenge for Developing Countries (Paris: OECD,

1994), p. 12.

17

Jeanne Kirk Laux, The Return to Europe: The Future Political Economy of Eastern Europe,

in Stubbs and Underhill, eds., p. 270.

15

Comparative Education Review

17

DALE AND ROBERTSON

The Three Regional Organizations: The European Union, the North American Free Trade

Area, and the Asia Pacific Economic Conference

It is important to note that each of these regional agreements reflects a

set of accumulated institutional relations and cultural and political practices,

which are the outcomes of struggles over particular agendas at particular

points in time. We should also note that these regional organizations are not

merely intelligible as a set of regional/national dynamics. Rather, regional

organizations are located in a complex web of global developments, such as

the WTO, the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), and supranational organizations such as the OECD, IMF, and World Bank; a particularly sharp instance of this can be found in the competing solutions to

the Asian Crisis (199798) put forward by the IMF and other regional organizations. These supranational and multilateral arrangements are important in understanding the differences between regional organizations and

their different relations with states.18

It is essential, therefore, to have a sharper picture of the differences

among the organizations that we will be looking at if we are to compare their

effects on education. We have found it useful to identify a set of variables

that might enable us to isolate better how the regional organizations vary.

We need, on the one hand, to understand their broad purpose and form

and, on the other, to devise a means of specifying more clearly the nature

and strength of their effect on national (or subnational) education systems.

These latter effects derive fromthough not in any direct or necessary

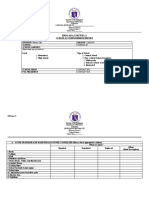

waythe organizations broad purposes and forms, and thus we might represent them diagrammatically as follows (see also fig. 1).

i) Form and purpose.the overall structure of the organization, its purposes, and how it achieves them.

ii) Dimensions of power (hard or soft).either one or some combination of

decisions, agenda setting, and establishing new rules of the game for states

and their education systems, where hard refers to the strength of influence.19 For example, the imposition of structural adjustment by the World

Bank might be viewed as hard, while learning or technical advice might be

viewed as softer, noncoercive forms of power.

iii) Nature of effect (direct or indirect).whether the impact upon education

occurs either directly or indirectly either on education politics (e.g., new

curricula, discourses about social exclusion) or the politics of education (such

18

See, e.g., Mark Beeson, Reshaping Reional Institutions: APEC and IMF in East Asia, Pacific

Review 121 (1999): 124.

19

See Steven Lukes, Three Distinctive Views of Power Compared, in The Policy Process: A Reader,

ed. M. Hill, 2d ed. (Hertfordshire: Wheatsheaf, 1997).

18

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

Fig. 1.Mapping the dynamics of globalization on education through regional organizations

as new governance rules and procedures, discourses about the knowledge

economy).20

iv) Processes/means of influence on the education system.the various strategies/tactics/devices that might be employedsuch as harmonization, borrowing, learning, imposition, benchmarking, advice, networking.21

v) Scope.the extent of the regional organizations influence on national/

subnational/local levels of education measured through changes in states

sovereigntylegislative power excluding all other authoritiesand its autonomyde facto capacity for independent development of the national

space.22

20

Here education politics refers to actions and decisions within the education system itself;

politics of education refers to global, national, and regional dynamics that set agendas and impose

limits on what is possible within education. For a fuller elaboration of this, refer to Roger Dale, Applied

Education Politics or Political Sociology of Education? Contrasting Approaches to the Study of Recent

Education Reform in England and Wales, in Researching Education Policy: Ethical and Methodological Issues,

ed. D. Halpin and B. Troyna (London: Falmer, 1994).

21

An earlier attempt to elaborate these mechanisms may be found in Roger Dale, Specifying

Globalization Effects on National Policy: A Focus on the Mechanisms, Journal of Education Policy 14

(1999): 114.

22

See Stephan Liebfried, National Welfare States, European Integration and Globalisation: A

Perspective for the Next Century, Social Policy and Administration 34 (2000): 4463, quote on 45.

Comparative Education Review

19

DALE AND ROBERTSON

Our argument is that not only may educations possible contribution to

human resource policy, or social policy, be viewed very differently across the

regions in terms of its overall content but also that the structures through

which it is administered and contested, and the extent to which education

might contribute to those overall purposes of the regional agreement, vary

considerably and with very different social, political, and economic

consequences.

The North American Free Trade Agreement

On January 1, 1994, NAFTA came into effect, tying together to an unprecedented degree the 363 million people and $6.3 trillion in economic

activity in Mexico, the United States and Canada.23 This agreement followed

the conclusion of the 1989 CanadianU.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA)

and involves the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The main mover of

NAFTA was the United States, and the primary purpose of the agreement

was to promote market liberalization and encourage capital flows across the

northern and southern borders of the United States.24 The means of doing

this was through softening or removing tariffs (border taxes) and establishing

a new set of rules of the game as to how, on what basis, with what scope, and

in what sectors trade would occur between the United States, Canada, and

Mexico.

The impetus behind NAFTA can be partially explained by the United

Statess particular response to the growing levels of nationalism in Canada,

which reached a high point during the 1970s.25 It was also a reaction to

Mexican laws that were seeking to regulate foreign investment and the transfer of technology, though Mexicos own stance toward the United States

softened in the 1990s when Mexico initiated talks with the United States.

However, Mexican and Canadian nationalism and efforts at nationalization

belie the extent to which economic dependence defined their respective

relationship with the United States.26 Porter observes that, like Canada, Mexico tried to offset the negative effects of this close economic relationship by

strengthening state intervention.27 By the 1970s, amid growing U.S. fear about

its economic lead, polite political notions such as special relationship were

replaced with a more aggressive set of goals related to the United States

23

Tony Porter, The North American Free Trade Agreement, in Stubbs and Underhill, eds., pp.

24553.

24

NAFTA accounts for only one-third of trade for the United States, and it is for that reason the

United States has sought regulation via the World Trade Organization (see N. Woods, Order, Globalisation and Inequality in World Politics, in Order, Globalisation and Inequality in World Politics, ed. A.

Hurrell and N. Woods [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999]).

25

Porter, pp. 24553. Porter notes that by the 1970s new Canadian government initiatives, such

as the Foreign Investment Review Agency, had sought to shape incoming investments in ways that were

more beneficial to Canadians.

26

Ibid., p. 246. For example, by the end of the 1970s, 70 percent of direct foreign investment and

foreign debt originated from the United States and 70 percent of Mexican exports were to the United

States.

27

Ibid.

20

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

seeking a more competitive position in the world; the creation of a new set

of rules with Canada and Mexico were part of this strategy. In particular,

reduced wages and stemming the tide of illegal Mexican immigrants were

central. Porter observes, the Americans aimed to obtain a nearby low-wage

location in which the labour costs of U.S. corporations could be reduced

(and their competitiveness thereby enhanced) by shifting parts of their production to Mexico. Allowing freer access for products made in Mexico to

U.S. markets was also seen as a way to stem the tide of illegal immigrants

from Mexico to the United States as the work done by these immigrants

could be done back south of the border.28

It was not part of NAFTAs purpose to create a social union between the

participating countries; nor was it intended to address the inequalities between them. Rather, as Brine observes, it formalizes [inequalities] . . . building . . . the inequality that exists between Mexico and the US/Canada into

its structure.29 Its goals were economic and were the expression of powerful

U.S. business constituencies. The NAFTA text is more than 2,000 pages of

precisely worded rules on areas such as greater market access in a variety of

sectors, investment rules, intellectual property rights, dispute settlement, and

side agreements on environmental and labor rights. Market access provisions

varied by sector, and NAFTA rules were not applied to some sensitive areas,

such as Canadian culture (e.g., education) and Mexican oil.30 Finally, in terms

of purpose, unlike the other two regional organizations, creating, extending,

or embedding a greater sense of what we might call regionness was not a

part of NAFTAs agenda.

In terms of its form, NAFTA is a highly precise set of rules that obligates

each of the partners. There are terms that ensure binding commitments and

these terms are not offset with opt out clauses. This is similar to the WTO;

the same drafters were involved in both NAFTA and the WTO. It was argued

that precision would (i) reduce transaction costs that might arise with ex post

facto governmental bargaining, (ii) provide a clear and calculable environment for trade where risks are known and their effects accounted for, (iii)

guide governmental bureaucrats in their decision making, and (iv) contribute

to overall transparency. As a result, within the NAFTA framework, regional

institutions lack the power to adopt supplementary legislation that might

modify the ongoing nature of the agreement. Only a modest level of authority

is delegated for the purposes of dispute settlement and this process is tightly

prescribed.

While this was intended to restrict the growth of a strong regional body

that might undermine U.S. autonomy and hegemony, its very tightness limits

28

Ibid., p. 247.

Jacky Brine, Undereducating Women: Globalizing Inequality (Buckingham: Open University Press,

1999), p. 18.

30

Porter, p. 248.

29

Comparative Education Review

21

DALE AND ROBERTSON

the ability of NAFTA to anticipate the future and modify regulations and

practices in light of change. What is evident here is what we will call, in

contrast to the EUs principle of subsidiaritydelegation of decisions to the

lowest possible level of governancethe principle of supersidiarity; decisions are made at the highest rather than the lowest level of activity and are

likely to result inat least for those areas of social and economic life that

are exposed to the agreementgreater regional convergence.

Is education policy and practice affected by NAFTA, and, if it is, what are

the processes or means of influence through which this occurs? The nature

of its effect on education policy and provision is largely indirect and occurs

through the way in which the rules of the game have changed for each of

the three participating states. As we will show shortly, these changes in the

rules have major consequences for states in how they think about the governance of education (i.e., who funds and provides it and, ultimately, how it

might be regulated). We noted that NAFTA was intended to increase trading

opportunities and encourage foreign direct investment among its parties and

the agreement itself is legally precise and binding. Under NAFTA, market

access is subject to national treatment. This means that imported goods coming into a country from another NAFTA country must be treated no less

favorably than domestic goods. The agreement views most public

goodssuch as educationas goods that might also be provided by the

market and, therefore, as tradable items under the same terms as other

tradable commodities. One of the clauses within the agreement related to

the rules of nationalization states that a public-sector goodsuch as the

provision of compulsory schooling and health carewas to be treated as if

it were a private good by the state and, therefore, as a site of investment

(e.g., privatizing schools), then it would fall under the rules concerned with

investment (in the case of Canada, by U.S. and Mexican investors). The rules

protecting investors, for instance, against risks that might return the privatized

schools to the public sector, would then be invoked. This is because nationalization of foreign enterprises on economic grounds is prohibited and all

nationalizations must be compensated properly at market rates. U.S. or Mexican companies, were they to be allowed to invest in education in Canada,

would have the same rights as investors in other industries; this means being

secure in the knowledge that like any other item of trade, the risks associated

with the investment are made transparent. Government intervention is viewed

as an unanticipated risk to an investor who would then need to be compensated for future lost earnings.

It is precisely this dilemma that faces the Canadian education system.

The privatization of education services, such as custodial and canteen services,

by a number of school boards in Ontario and Alberta, and the privatization

of aspects of provisionas in the case of charter schools in Alberta with

private companies, such as Education Alternatives, keen to investmeans

22

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

these companies would have to be compensated at market rates for future

lost earnings if they were to become renationalized.31 Thus, though NAFTA

has little to say directly about education, states are limited in what autonomy

they have to make decisions about their governance of schools and risk a

degree of loss of sovereignty if NAFTA rules are invoked. Nervousness about

the consequences for service areas such as education and health care has led

to a considerable amount of public lobbying and organizing around the

privatization agenda in NAFTA countries.

States face these same dilemmas when it comes to the higher education

sector. Universities are viewed as important powerhouses for research and

development within the region, able to contribute economic development

within the global economy. Universities are thus sites for investment in research and development. All the NAFTA partners, in particular Mexico, because of its different and variable level of resources, are faced with the potential dilemma of being able to direct universities as they open up to private

investors, while universities may well find themselves unable to direct their

own activities.32 It is argued that blurring the boundaries within the university

sector (e.g., between public and private activity), when linked to matters of

intellectual property, will reduce the autonomy universities have long claimed

and open the doors for a much more competitive and entrepreneurial site

that looks very different from the enlightenment university.

In terms of its processes and means of influence on education, then,

NAFTAs strategy may be seen as seeking to embed free trade and to extend

it to an area of previously public-dominated provision by employing the tactic

of binding trade agreements and the devices that accompany them, such as

dispute-resolution procedures. In terms of the extent of its influence on

national education policy, its effect is on the sovereignty rather than the

autonomy of its members. That is to say, it sets limits on the areas where they

can determine policy but not on how they make use of the sovereignty that

remains.

European Union

Any consideration of the EUs role in national education policy has to

take into account its constant evolution.33 To do justice to that evolution

would require a full-blown and detailed chronology, for which we have no

space here.34 To address that in part, we have chosen to identify two particular

31

See Susan Robertson, Victor Soucek, Raj Pannu, and Daniel Schugurensky, Chartering New

Waters: The Klein Revolution and the Privatization of Education in Alberta, Our Schools Ourselves 7

(1995): 80106.

32

Guillermo de los Reyes, NAFTA and the Future of Mexican Higher Education, Annals of the

American Academy for Political and Social Science 550 (March 1997): 17.

33

The current members of the European Union are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France,

Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United

Kingdom.

34

For the early period, see Jacky Brine, Educational and Vocational Policy and Construction of

the European Union, International Studies in Sociology of Education 5 (1995): 14563.

Comparative Education Review

23

DALE AND ROBERTSON

points in time, the period culminating around the mid-1990s and the most

recent proposals for education that emerged from the Lisbon Summit in

2000. We will contrast these periods across each of the dimensions we have

proposed. We should note here that we have considered only the level of

compulsory education because this remains very much the legal responsibility

of member states; the EUs activity in the areas of higher education and

vocational and technical education is much greater.

The idea of a community of European nations grew out of a desire to

maintain peace after World War II. This was a political plan focused upon

economic ties; in 1957 the Treaty of Rome established the European Economic Community. Purdy observes that the EUs initial purpose was also

informed by a view that market liberalization might meet aspirations for

higher wages and social expenditure as a result of economies of scale and

rapid growth.35 In the following decades, as more countries were admitted,

there was a growing realization that European integration had to be more

than an economic union. That is, if the effects of rising unemployment as a

result of economic restructuring were to be managed and events such as the

1968 demonstrations avoided, there needed to be a union of people that

might be brought about through wider political, economic, and social policies. The later change in title to the European Union reflected this broader,

more social, perspective. The European Union then can be seen both as an

economic agreement that facilitated trade liberalization and investment and

as a social and political union.

The initial scope of social policy was explicitly confined to matters affecting employees rather than citizens. Further, on these matters, the role of

the commission was, and continues to be, restricted to conducting research

and offering opinions. This is largely because social policy was initially assigned a minor role where the emphasis was on standardizing access to the

market through law (in particular, labor mobility and the impact of internal

free trade on working conditions, wages, and social insurance). Political and

social rights thus remained matters of national responsibility until 1984, when

Jacques Delors was appointed president of the commission. Delors seized the

opportunity presented by the Single Market program to propound the idea

that social cohesion was just as important as market integration.36 However,

even then, the preoccupation with employment, as under the initial provisions

of the Treaty of Rome, remained, thereby confining the scope of social policy

to matters affecting employees rather than citizens. In contrast with NAFTA,

where the provision of social programsand therefore educationis viewed

rather like any other tradable good or service, social provision within the EU

is conceptualized as a social and public investment in current and future

35

David Purdy, Social Policy, in The Economics of the European Union, ed. M. Artis and N. Lee, 2d

ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 284.

36

Ibid., p. 281.

24

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

workers that will potentially secure social cohesion and social stability. However, Delorss 1993 White Paper on Growth, Competition and Employment

stressed the importance for Europe of intangible investment, particularly in

education and research, with investment in knowledge playing an essential

role in European competitiveness and social cohesion.37 This reflected a more

activist conception of social policy, though again the focus was on the human

resources necessary for a competitive regional workforce within the global

economy.

By the time of the Lisbon Summit, education had become more central.

Consistent with the will to promote social policy as a productive factor,38

and the EUs new strategic goal for the next decadeto become the most

competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable

of sustainable growth with more and better jobs and social cohesion,39 education is deeply implicated in two of the three aspects of the overall strategy

proposed to achieve this goalpreparing the transition to a knowledgebased economy and society by better policies for the information society and

Research and Development . . . [and] modernising the European social

model, investing in people and combating social exclusion.40 The concrete

implications of these proposals for education call for emphases on raising

the standards of learning by improving the quality of training for teachers;

facilitating lifelong learning; updating the definition of basic skills, especially

through information technology (IT) skills training; facilitating labor mobility; and introducing quality-assurance mechanisms to better match resources to needs to enable schools to support their new, wider role.41 Its

purpose in respect to education, then, is very broad, covering not only infrastructural support but also a high degree of regionness.

In terms of form, the legal basis of EU social policy is set out in the Treaty

of Rome (1957) and modified by the Single European Act (1986) and the

Treaty of European Union (1992). The role of education as a tool for assisting

changes in an evolving European society was gradually acknowledged, and

the first action plans in the field of education were put into place. However,

it is crucial to note that it remains very much a national responsibility. Article

126 limits the EU to supporting and supplementing national education

systems, though Article 149, which allows the community to contribute to

the development of quality education . . . while fully respecting member

States control of content and organisation does offer something of a loophole that has been more recently used.

37

European Commission, White Paper, Growth, Competitiveness and Employment: The Challenges

and the Way Forward into the Twenty-First Century (Brussels, 1993).

38

See European Commission, Proposal for Decision of EU Parliament and Commission, Presented to Lisbon

Summit (Brussels, 2000).

39

European Commission, Lisbon European Council: Presidency Conclusions (Brussels, 2000), par. 5

40

Ibid.

41

See Commission of the European Communities, Report from the Commission: The Concrete Future

Objectives of Education Systems (Brussels, 2001). Executive summary.

Comparative Education Review

25

DALE AND ROBERTSON

Thus, although the very existence of the EU imposes some degree of

commonality, the possibility that initial divergences might eventually wither

away has so far been blocked by fundamental disagreements, both about the

proper scope and objects of social policy and about the proper division of

responsibility and power between the union and its member states.42 Indeed,

to make aspects of the EU acceptable, especially in relation to social policy,

serious recognition of the principle of subsidiaritythat is, delegation to

the lowest possible level of governancehave been necessary.43

The EU has, of course, a very powerful bureaucracy in the form of the

European Commission, which now has a separate Directorate General for

Education and Culture. This, too, has developed over the EUs history. Writing

of the pre-1995 period, Jacky Brine comments that the demands of legislation, the influence of policy documents, and the allure of funding are the

main means by which [the] construction of the union of the European nation

states takes place.44 By the Lisbon Summit, not only was there the Directorate

General for Education and Culture but wider use was being made of the

possibilities of Article 149in particular through the development of common indicators and benchmarks.45 This is very much a part of the new Open

Method of Coordination (OMC), which was put forward by the Lisbon Summit and seems set to become the major means through which the EU education (and other social) policy will be developed.46 It essentially involves

fixing guidelines for the Union, combined with specific timetables for achieving the goals which they set; . . . establishing, where appropriate, quantitative

and qualitative indicators and benchmarks against the best in the world and

tailored to the needs of different Member States and sectors as a means of

comparing best practice; translating these European guidelines into national

and regional policies by setting specific targets and adopting measures, taking

into account national and regional differences; and periodic monitoring,

evaluation and peer review.47 The potential of the method was recognized

in a paper prepared for the Education Ministers Meeting held in May 2000

at Bucharest (significantly, acceding countries are included in many of the

new initiatives). In this paper it is suggested that indicators lead to benchmarks, to issues and questions and thence to examples of good practice which

provide a focus for policy development in every European country.48 It was

also recognized that national goals and policies differ and will continue to

42

Purdy, p. 289.

John Grahl and Paul Teague, Is the European Social Model Fragmenting? in The Welfare State

Reader, ed. Christopher Pierson and Francis Castles (Cambridge: Polity, 2000).

44

Brine, Educational and Vocational Policy, pp. 14647.

45

European Commission, Directorate-General for Education and Culture, Developing Quality Indicators for Education Systems (Brussels, 1999).

46

See European Commission, Constructing New Programmes in Education (Brussels, 1999).

47

European Commission, Lisbon European Council: Presidency Conclusions, par. 37.

48

European Commission, Directorate-General for Education and Culture, European Report on

Quality of School Education: Sixteen Quality Indicators (paper prepared for Education Ministers Meeting, Bucharest, May 2000 [Brussels, 2000]), p. 4.

43

26

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

differ, but much may still be learned from innovative practice and new and

different approaches to old problems. As the Report on Concrete Future Objectives

of Education Systems post-Lisbon concludes, the objectives set out in the report

cannot be achieved by member states alone and thus need cooperation at

European level.49

It should by now be clear that the EU does affect various elements of

member states policies through all three of the dimensions of power. It can

make rules and decisions that are binding on members; it clearly determines

particular agendas to which all member states (and, it should be added,

acceding members) have to pay heed and respond (even where these are

not formally restricted or binding); and it sets the rules of the game, through

the effects it has on overall national policy direction in other sectors, the

ways it divides up sectoral responsibilities, and the sticks and carrots it provides

to follow particular programs. These powers have been more or less available

throughout the EUs history, but it seems clear that agenda setting and the

rules of the game have been given greater prominence in the later phases

of the periods we are looking at, given the continuing strength of the prohibition on intervention in national educational decision making and the

continuing attachment of many members to the subsidiarity principle. We

see this especially in the introduction and likely future importance of the

OMC.

We should not ignore, however, another form of influence that operates

as a result of the existence of the EU. We might call it an enhanced institutional and discursive thickness, which is the outcome of the development of Euro-networks of all kinds, initially linked directly with the

Community or Commission, but more recently growing independently in

the form of lobby groups, professional associations, conferences, mutual

recognition of a possible European agenda, or of joint possibilities of European-funded research, and the creation of professional journals with a

European focus. Most of this work is formally independent of the EU, but

it does have some role in shaping national education policies in ways influenced by the existence of, and to some degree the agendas of, the EU.

It would be unfortunate to overlook this form of regional effect on education, particularly because it is one that clearly distinguishes the EU from

the other two regional organizations.

When we come to look at the processes and means of influence through

which the EU operates in the field of education, we notice a number of

similarities with the last group. In particular, the change over time becomes

quite evident. In terms of strategy, there have been significant changes since

the early 1990s, before which education initiatives were based on the Maastricht Treaty and especially on Article 126, which made education very much

a national responsibility. Brine, writing in 1995, could conclude that the

49

Commission of the European Communities.

Comparative Education Review

27

DALE AND ROBERTSON

European dimension in education, . . . has as its main purpose, within

compulsory education, the attempt to build a shared cross-national understanding of what it means to be European.50 Whether or not faute de mieux,

the EUs influence on compulsory education was restricted to the advancement of a Eurodimension in national education programs, and whatever

(sometimes not inconsequential) spin-offs might be obtained from interventions in the areas of vocational training and higher education, where the

treaty did allow it to intervene. The main tactic employed, as we suggested

above, was the promotion and funding of relatively small-scale programs,

such as Comenius (whose overall objectives are to enhance the quality and

reinforce the European dimension of school education, in particular, by

encouraging transnational cooperation between schools),51 though the European Social Fund could also be useful as a means of funding some initiatives.52 This restricted the possible means employed to meetings of experts

and other interested parties for the development of programs, some limited

interschool networking, and school and student exchanges.53

Since the mid-1990s, there have been significant changes in all three

areas. The strategy has been associated with increasing emphases at all levels

of the EUs work on promoting the knowledge economy and lifelong learning, in which education is taken to be central. This change might be seen

as a shift from vertical to horizontal cooperation, and from harmonization

to coordination as an ideal. It is intended to involve, in particular, renewed

emphases on quality, IT, science, and technology and access to opportunities

for learning. The tactics have shifted from promoting the Eurodimension to

bringing about much greater levels of coordination of national education

policies by means of the OMC. And the means used derive directly from this

tactic. They center on benchmarking and performance indicators as a means

of bringing together different national goals and aspirations for education

in a more coherent way at the European level.

The final variable of external influence on national education systems is

its scope, measured by its effects on national and subnational systems and

the means by which it is achieved, through effects on national sovereignty

or autonomy. It is clear in the case of the EU that it has effects on both

levels. While its influence on national sovereignty in the education sector is

extremely limited, as we have seen above, it is able to have considerable effect

on how its members exercise their autonomy in the area of education policy.

We might consider here a case in which both sovereignty and autonomy

50

Brine, Educational and Vocational Policy, p. 161.

See More Information about Comenius, http://www.europa.eu.int/comm/education/socrates/comenius/moreabou.htm. For a useful evaluation of the effect of the Comenius program on schools

across member states, see John Field, European Dimensions: Education, Training and the European Union

(London: Jessica Kingsley, 1998), pp. 1015.

52

Brine, Educational and Vocational Policy, p. 152.

53

See Field, chap. 4.

51

28

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

have been influenced by the EU and the mechanisms through which this

has taken place. The case of Scotland is particularly informative, partly as its

subnational status opens up the possibility of it being both directed by national

policy yet also able to respond to supranational policy if and should it choose

to do so. Livingstone observes that there has, since the early 1970s, been an

office in Edinburgh actively promoting European links and exchanges.54 The

1988 resolution regarding the promotion of European culture prompted

a response from the United Kingdom, which for this purpose included Scotland. However, while Whitehall was responsible for creating an official framework to encourage good practice and dissemination, the Scottish Education

Officewhich had a degree of devolved responsibility for education in Scotlandwas responsible for its implementation. The policy also encouraged

support for language learning and teaching and bilateral links and exchanges.

These links have been consistently pursued with some degree of institutional

formality. For example, in 1990 the Scottish Office set up an International

Relations Branch; two of its objectives are of note: the provision of easy access

to information about the EU and the establishment of a number of networks

to facilitate the development of a European dimension.55 These have been

followed by publications, conferences, curricular materials, and inclusion of

a European dimension in teacher-training programs.

Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation

The APEC forum has an extremely large and diverse membership. Its 21

members include not only all three members of NAFTA but the worlds three

largest economies (the United States, China, and Japan) and Russia, which

joined recently.56 Together they account for almost half of all world trade.

The diversity of its membership distinguishes APEC from the other two organizations. The membership covers the whole range of national wealth, from

the United States to Papua New Guinea. There are distinct cultural and

religious differences among the members, and many of them have education

systems that continue to bear (rather different) traces of their colonial histories, so that, overall, there is a correspondingly broad diversity of educational systems and provisions. Furthermore, to a much greater extent than

in the other two cases, there are other subjects of globalization, such as

the World Bank, the Asia Development Bank, and UNESCO, at work in the

education field in the APEC region. Sylvia Ostry places great emphasis on

54

Kay Livingstone, The European Dimension, in Scottish Education, ed. T. G. K. Bryce and W. M.

Humes (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), pp. 93746, quote on p. 941.

55

Ibid., p. 942.

56

APECs membership is made up as follows. The founding members were Australia, Brunei

Darussalam, Canada, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Phillipines, Singapore,

Thailand, and the United States. In 1991, they were joined by the three Chinas, the Chinese Peoples

Republic, Hong Kong (later Chinese Hong Kong), and Chinese Taipei; it is the presence of the PRC

and Taiwan in the same organization that led to it being called a conference of regional economies.

Mexico and Papua New Guinea were admitted in 1993, Chile in 1994, and Peru, Russia, and Vietnam

in 1995.

Comparative Education Review

29

DALE AND ROBERTSON

the importance of international nongovernmental organizations in the development of APEC.57

APEC was originally proposed in 1989 by the thenprime minister of

Australia Bob Hawke as a kind of Asian OECD and was set up, with considerable support from Japan, in the form of a ministerial-level meeting

of twelve economies. The stimulus to its creation at that time was in large

part a response to the deregulation of the international finance system

and the competition for foreign direct investment, together with the fear

of exclusion from two projectionist regional blocs . . . a Fortress Europe

and a Fortress North America.58 However, by 1993, trade liberalization

had become the most important of its three pillarsthe others were trade

facilitation and technical cooperation. A key feature that adds to the difficulty of precise definitions of APECs purpose is the existence of what

John Ravenhill calls competing logics between its Asian and Western

members; Asian preferences for lack of specificity in agreement and an

informal incremental bottom up approach to regional co-operation were

juxtaposed with Western models based on formal institutions established

by contractual agreements.59

There have been more recent attempts to give a higher profile to Ecotech

(economic and technical cooperation, a term that replaced development

coordination at the 1995 Osaka meeting), where we find the most explicit

references to education. These concentrate on capacity-building in the lessdeveloped economies of the region and may be seen as a form of economic

development assistance without the negative connotations of neocolonialism

or the conditionalities of loans from international financial institutions. Possibly associated with this has been the development of what Ravenhill calls

a community building60 or what Higgott calls an identity building purpose

on the part of the Asian members.61 Higgott suggests this may form the basis

of Asian positions on some issues, arguing that it may have been considerably strengthened by their collective hostility toward both the content and

the manner of the IMF-imposed solution to the Asian economic crisis of

1997.

However, while education does not appear to have a very high priority

in APEC, it remains a matter of interest and importance outside the region

as well as within it because of its perceived contribution to the economic

57

Sylvia Ostry, APEC and Regime Creation in the Pacific: The OECD Model, in Asia-Pacific

Crossroads: Regime Creation and the Future of APEC, ed. Vinod K. Aggarwal and Charles E. Morrison (New

York: St. Martins, 1998), pp. 31750.

58

Ibid., p. 343.

59

John Ravenhill, Australia and APEC, in Aggarwal and Morrison, eds., pp. 14364. Quoted in

Miles Kahler, Legalization as Strategy: The Asia-Pacific Case, International Organisation 54 (2000): 557.

60

Ravenhill, APEC Adrift: Implications for Economic Regionalisation in Asia and the Pacific,

Pacific Review 13 (2000): 320.

61

R. Higgott, The Political Economy of Globalisation in East Asia: The Salience of Region Building, in Globalisation and the Asia-Pacific: Contested Territories, ed. K. Olds, P. Dicken, and P. F. Kelly

(London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 91106.

30

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

success of the Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and

Taiwan). Morris quotes The Economists conclusion on the basis of the Tigers

success: the last lesson is probably the most important: investing in Education

pays off in spades. The tigers [sic] single biggest source of comparative

advantage is their well-educated workers, and he comments, Increasingly

the Asian experience is portrayed as providing an exemplary model for those

societies suffering from low or declining levels of economic growth.62 This

suggests that there may be a predisposition to emulate the educational policies

of the Tiger economies that exists alongside, as well as through, the medium

of APECs efforts in the sector.

The most direct moves to include education in APECs work have been

the two meetings of education ministers, the first in 1992 and the second in

April 2000. At the 2000 meeting the ministers committed themselves to meeting every 5 years. The ministers at the first meeting, held in Washington,

D.C., saw it as affirming the direct link between education and economic

development and emphasized educations crucial role in human development; they recognized the need to continue to work cooperatively to identify

strategies for addressing the challenges presented to their education systems,

[including] . . . the need for students to develop the skills required in a

technologically sophisticated world and a better understanding of the cultures

and economies of the Asia-Pacific region.63

These themes were specified somewhat differently at the 2000 meeting

in Singapore, where there was recognition that high standards in literacy,

mathematics, science and technology provide the necessary foundation

needed for the new global economy, with a strong emphasis on IT in

schools.64 Evidence of perhaps a bigger role for education comes in the

statement that in recognition of the need to constantly adjust the focus of

education efforts to prepare for an ever changing world, the ministers had

decided to rename the APEC Education Forum set up at the 1992 meeting

the APEC Education Network; significantly, it is to be part of the threenetwork structure of the Human Resource Development Working Group.

At the 2000 meeting the ministers identified four strategic areas for transforming their education systems to become the foundation and impetus for

Learning Societies: (1) sharing ideas, experiences, and best practices on

the use of IT, as a core competency in education, through physical or virtual

exchanges, networks and programs; (2) enhancing the quality of teacher

development, through sharing effective teaching and teacher development

62

Paul Morris, Asias Four Little Tigers: A Comparison of the Role of Education in their Development, Comparative Education 32 (1996): 99.

63

APEC, Declaration of the APEC Education Ministerial, Towards Educational Standards for the

Twenty-First Century (Singapore, 1992), http://www.apecsec.org.sg/virtualib/minismtg92.html, par. 2,

3.

64

APEC, Joint Statement of the Second APEC Education Ministers Meeting, Education for

Learning Societies in the Twenty-first Century, Singapore, 7 April 2000, in Selected APEC Documents

(Singapore, APEC, 2000), pp. 2936, quote in par. 9.

Comparative Education Review

31

DALE AND ROBERTSON

practices; (3) cultivating sound management practices among policy makers

and practitioners through exchange of information and expertise; and (4)

promoting a culture of active engagement to forward understanding within

the Asia-Pacific community, through teacher and student exchanges.

The organizational form of APEC quite deliberately rejects both the EU

harmonization/cooperation models and NAFTAs rules-based approach, reflecting a fear of domination by the United States or Japan. APEC has always

been characterized by what Kahler calls the ASEAN model of incremental

institutionalization and low legislation.65 This reflects the historically nonlegalized culture of much of Asia as well as lack of agreement on particular

objectives that might structure the activities of APEC. Finally, APECs capacity

is limited by the provision of only a small secretariat that relies heavily on

working groups to arrive at consensus, and by the absence of any financial

levers.66 The agenda of annual meetings is determined by the host economy,

which sets limits to consistency and continuity and means that the outcomes

in policy terms reflect this ad hoc, episodic nature of the forum. All of this

has contributed to what Ravenhill calls the largely incoherent process by

which projects proliferated their weak links to APECs core activities and the

failure of most of them to generate substantive outcomes.67

In the education area, the principles of participation set out at the first

ministerial meeting are that participation should be open to all APEC members. Specific cooperative initiatives may be proposed by any individual member or group of members that so desires. Participation in any given initiative

is open to all members, but such participation is voluntary. Members participating in an initiative would be responsible for identifying the resources

required to carry it out.68 The renamed Education Network (whose participants come from members ministries of education) elaborates this a little,

with lead economies taking responsibility in distilling strategic statements

for each main theme identified by the ministerial meeting, and working

groups then developing the projects. There is no capacity for monitoring the

outputs or outcomes of the projects.69

In terms of the other elements of figure 1, then, we may see APEC

operating in the education area, as in all other areas, with a very soft and

65

Kahler, p. 551.

Kahler quotes Janow as arguing that its members have shown little willingness to formalise APEC

by means of binding agreements on a defined set of substantive economic or trade issues nor have its

members sought to create a regional institution with rule making, interpretative, enforcement, or adjudicative powers (p. 558).

67

Ravenhill, APEC Adrift, p. 325.

68

Examples of the kinds of project undertaken include Vocational Teacher Standards and the

Formulating Method (China); Best Practice Workshop on School-to-Work Transitions (Canada);

Achieving High Performance Schools (China and the United States); Improving the Understanding

of Culture in APEC (Australia); Exchange of Education Professionals among APEC Members (Korea);

and APEC Youth Networking: Youth Preparation for the APEC Society in the Next Millennium

(Thailand).

69

APEC, par. 12. http://apecsec.org.sg/virtualib/minismtg/mtgedu92.html.

66

32

February 2002

REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AS SUBJECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

indirect form of power. (It is crucial to note that not only on this variable

but also on all the others we discuss, the great diversity of the membership

means that the effects will be experienced very differently by different members. However, we should note that this diversity is rarely, if ever, mentioned

in discussions and reports within APEC.) It is neither able to nor wishes to

make decisions that are binding on its members. Its method of concerted

unilateralism (which Ostry describes as voluntary liberalization encouraged

by peer group pressure),70 however, does suggest that an element of agenda

setting is considered desirable, and this is clearly evident in the readiness to

identify and disseminate best practice in areas of education, and to enable

the growth of networks that focus on topics determined interesting by the

collectivity of the members.

In terms of the nature of the effect, there is no capacity for a direct

influence on either the politics of education or education politics. It seems,

unlikely, however, that the relentless emphasis on the instrumental contribution of education to economic development, and the attaching of the great

majority of its education activities to that end, does not have an effect on

the politics of education, especially in the less-developed economies. At the

level of education politics, there is potential for a somewhat more direct

effect through the emphasis on activities like sharing best practice, benchmarking, educational exchanges, and professional networking.

We can infer the processes and means of influence quite directly from

the examples given above. The formal strategy might be seen as one of

cooperative action to enhance the contribution of education to economic

development in the region as a whole. This should not entail any imposition,