Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Contemporary Nurse Volume 20 Issue 2 2005 (Doi 10.5172 - Conu.20.2.234) Taylor, Beverley Holroyd, Beth Edwards, Paul Unwin, Anna Row - Assertiveness in Nursing Practice - An Action Research and Re

Enviado por

Hendri HariadiTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Contemporary Nurse Volume 20 Issue 2 2005 (Doi 10.5172 - Conu.20.2.234) Taylor, Beverley Holroyd, Beth Edwards, Paul Unwin, Anna Row - Assertiveness in Nursing Practice - An Action Research and Re

Enviado por

Hendri HariadiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

This article was downloaded by: [University of Otago]

On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:48

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG

Contemporary Nurse

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcnj20

Assertiveness in nursing practice: An

action research and reflection project

a

Beverley Taylor , Beth Holroyd , Paul Edwards PhD Candidate ,

c

Anna Unwin & Joanne Rowley PhD Candidate

Foundation Chair in Nursing Southern Cross University, Lismore

campus, Lismore, New South Wales

b

Mental Health Nurse Coffs Harbour Health Campus, Coffs

Harbour, New South Wales

c

Nurse Educator Coffs Harbour Health Campus, Coffs Harbour,

New South Wales

d

Nurse Researcher Coffs Harbour Health Campus, Coffs Harbour,

New South Wales

Published online: 17 Dec 2014.

To cite this article: Beverley Taylor, Beth Holroyd, Paul Edwards PhD Candidate, Anna Unwin &

Joanne Rowley PhD Candidate (2005) Assertiveness in nursing practice: An action research and

reflection project, Contemporary Nurse, 20:2, 234-247, DOI: 10.5172/conu.20.2.234

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.5172/conu.20.2.234

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or

arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

Copyright eContent Management Pty Ltd. Contemporary Nurse (2005) 20: 234247.

Assertiveness in nursing practice: An

action research and reflection project

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

ABSTRACT

Key Words

action research;

reflective

practice;

assertiveness;

nursing practice

This article describes an action research project that highlighted reflective

processes, so hospital nurses could work systematically through problem solving

processes to uncover constraints against effective nursing care; and to improve the

quality of their care in light of the identified constraints and possibilities. Four

Registered Nurses (RNs) co-researched their practice with the facilitator and

over the research period identified the thematic concern of the need for

assertiveness in their work.The RNs planned, implemented and evaluated an

action plan and, as a direct result of their reflections and collaborative action,

they improved their nursing practice in relation to becoming more effective in

assertiveness in work situations.

Received 5 August 2005

Accepted 27 October 2005

BEVERLEY TAYLOR

PAUL EDWARDS

Foundation Chair in Nursing

Southern Cross University, Lismore campus

Lismore, New South Wales

PhD Candidate and Mental Health Nurse

Coffs Harbour Health Campus

Coffs Harbour, New South Wales

BETH HOLROYD

ANNA UNWIN

Mental Health Nurse

Coffs Harbour Health Campus

Coffs Harbour, New South Wales

Nurse Educator

Coffs Harbour Health Campus

Coffs Harbour, New South Wales

JOANNE ROWLEY

PhD Candidate and Nurse Researcher

Coffs Harbour Health Campus

Coffs Harbour, New South Wales

234

CN

CN

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

Assertiveness in nursing practice

INTRODUCTION

LITERATURE REVIEW

ursing in hospitals involves negotiating

complex interpersonal relationships and

working in a social and political context within

economic constraints, while balancing a multiplicity of tasks and roles. Nurses are busy clinicians who need to have a broad range of clinical

knowledge and skills, and they are accountable

to many people (Benner 1984; Benner and

Wrubel 1989; Taylor 1997, 2000). Hospital

nurses are caught up in the complexity and

busyness of daily work, but these constraints can

be managed effectively by reflective processes

(Freshwater 2002;Taylor 2000).

This article describes an action research

project that emphasised the value of reflective

practice through which nurses identified the

thematic concern of assertiveness at work.This

article describes the project in terms of its

background, methodology, methods, processes

and insights.The action plan the nurses generated and instituted for practising assertively is also

described.

Assertiveness is an important issue in nursing

practice. After a period of reflective practice,

when the nurses in this project identified their

need for assertiveness at work, the literature

was explored with the intention of assisting in

the creation of the action plan. Nursing literature repeats the call for nurses to become more

assertive (Gaddis 2004; Levesque 2003; Madden 1996; McNally 2002; Milstead 1996; Morris 2004; Kupperschmidt 1994; Larson 1997;

Pacquiao 2000; Pauly-ONeill 1997; Smith

1997). Education programs in assertiveness

knowledge and skills have been in vogue for

some time in nursing because nurses have

recognised the need for assertiveness in quality

nursing care (Benton 1999; Cardillo 2003;

Class 2001; Crouch 2003; Floyd 1999, 2001;

Habel 2004; Lyttle 2001; McCabe & Timmins

2003; Milstead 1996; Pearce 2004; Percival

2005, 2001, 2000; Stein-Parbury 2005;Woods

2003). All of these authors agree that assertiveness is important in nursing practice, but that it

is complex and requires time and practice to

make it effective.

This review describes some recent nursing

research into assertiveness (Addis & Gamble

2004; Jaime et al. 1998; McCartan & Hargie

2004a,b; Timmins & McCabe 2005). Timmins

and McCabe (2005) undertook a preliminary

pilot study to assess how assertive nurses are in

the workplace, in order to develop an instrument and report on the results.The researchers

distributed the 44-item questionnaire to 27 registered nurses and the results showed that nurses in the study responded strongly to items

allowing others to express opinions, complimenting others and saying no (Timmins and

McCabe 2005:61). The researchers concluded

that the nurses behave in a passive, nice way and

were less adept at disagreeing with others

opinions and providing constructive criticism

(Timmins and McCabe 2005:61). Even though

this project has been reported as a preliminary

pilot study, the results should be viewed cau-

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

CN

AIM, OBJECTIVES, SIGNIFICANCE

AND BACKGROUND

This project aimed to facilitate action research

and reflective practice processes in experienced

Registered Nurses in order to:

raise critical awareness of practice problems

they face everyday;

work systematically through problem solving

processes to uncover constraints against

effective nursing care; and

improve the quality of care given by hospital

nurses in light of the identified constraints

and possibilities.

The significance of the project was in improving

nursing care and in educating nurses in a

research process they can use for clinical problems that emerge daily in their practice.

The project originated through collaboration

between a School of Nursing and practice-based

nurses.

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

CN

235

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

CN

Beverley Taylor et al.

tiously because of low sample numbers and the

tendency for questionnaire respondents to indicate nice or self-fulfilling behaviours, even if

they practice in a contrary way, by using active

assertion in their workplace.

Addis and Gamble (2004:452) aimed to

understand what nurses had learned from an

assertive outreach (AO) experience.The project

was informed by the phenomenological concepts of Heidegger and data were collected

through the use of semi-structured interviews

of five rural AO nurses working in one county

in England. The thematic analysis revealed that

nurses understood their experience of assertive

engagement as involving: having time; anticipatory persistence and tired dejection; pressure,

relief and satisfaction; being the human professional confluence; accepting anxiety and fear;

working and learning together; and bringing the

caring attitude. Thus it was shown that being a

rural AO nurse involves contradictory yet

rewarding experiences in practising assertive

behaviours with clients.

McCartan and Hargie (2004a:707) administered The Caring Assessment Instrument and

the Assertion Inventory to a convenience sample

of 94 nurses to find answers to their research

question, Assertiveness and caring: are they

compatible? The background to their project

was that numerous assertion studies suggest

that nurses are generally non-assertive, so they

wanted to determine whether positive and negative assertion behaviours were related to caring

skills. The researchers defined positive assertion as:

other-centred caring type behaviours such as

expressing positive feelings, initiating and

maintaining interactions, giving and receiving

compliments, and conveying empathy.

(McCartan & Hargie 2004a: 707708)

Negative (standard conflict) responses are often

viewed as self-centred skills and may be considered undesirable attributes in nursing (McCar236

CN

tan & Hargie 2004a:708). After analysis of the

nurses responses, they concluded that:

Overall the findings of the study suggest that

positive and negative assertive behaviours are

not related to caring skills The current

findings suggest that the presence of caring

attributes cannot be offered as a possible reason for non-assertion in nurses.

(McCartan & Hargie 2004a:707)

McCartan and Hargie (2004b) distributed the

Bem Sex-Role Inventory and the Assertion

Inventory to a convenience sample of 94 subjects, to determine the effects of nurses sex

role orientation on positive and negative assertion.The researchers reported that contrary to

earlier studies, the findings of the investigation

indicated that there was no significant relationship between assertion measurements and sexrole orientation (McCartan & Hargie 2004b:

45). The findings of the research projects by

McCartan & Hargie (2004a,b) demonstrate difficulties in making exact statements about

assertiveness and suggest that its success is relative to the contexts in which nurses enact it.

The research question posed by Jaime et al.

(1998:98) was whether assertiveness is a characteristic of the nursing profession. Their

descriptive study aimed to determine the

degree of assertiveness in nurses and to assess

the influence of personal characteristics, such as

age, sex, marital status, work experience and

place of employment. A questionnaire measuring the degree of assertiveness in professional

environments was distributed to 75 nurses

working in acute care settings in three Spanish

hospitals.The results showed qualitative differences according to personal characteristics

although these were not statistically significant,

and a high percentage of nursing professionals

showed low degrees of assertiveness (Jaime et

al. 1998:98). The researchers concluded that

given the low degree of assertiveness in the

research sample, assertiveness training was necessary to improve the quality of health care.

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

Assertiveness in nursing practice

CN

Their conclusions assume that caring and

assertiveness are linked and that assertiveness is

essential in the provision of quality nursing care.

In summary, nursing research literature

emphasises the need for nurses to become more

assertive and to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to make nurses assertiveness

more apparent in their workplaces.

water 1999), and education (Anderson &

Branch 2000; Clegg 2000; Cruickshank 1996

Freshwater 1999; Kim 1999; Platzer et al.

2000). Much of the literature focuses on the

work of nursing as practised in clinical contexts

(e.g., Freshwater 1998, 2002; Glaze 1999;

Heath 1998a,b; Johns 2000, 2003;Taylor 2004.

2003, 2002a,b;Wilkin 2002).

METHODOLOGY

Action research

Action research involves four stages of collectively planning, acting, observing and reflecting

(Dick 1995; Stringer 1996).This phase leads to

another cycle of action in which the plan is

revised, and further acting, observing and

reflecting is undertaken systematically to work

towards solutions to problems of a technical,

practical or emancipatory nature (Kemmis &

McTaggart 1988;Taylor 2000).

Nurses have been using action research

successfully in a variety of settings focusing

on differing thematic concerns (e.g., Keatinge

et al. 2000; Koch, Kralik & Kelly 2000;

Chenoweth & Kilstoff 1998). Action research

and reflective processes combine well methodologically because of their common interest

in making sense of experiences, in order to

progress to deeper insights and personal and

professional changes. Research using action

research and reflection has been successful in

giving nurses contextual answers to practice

issues such as dysfunctional nursenurse relationships (Taylor 2001b) and nurses tendencies

towards idealism in palliative care (Taylor et al.

2002).

In qualitative research, methodology usually

means the theoretical assumptions of how

knowledge is generated and validated, which

underlie the choice of methods. Given the collaborative nature of the project, a qualitative

approach was chosen, informed by reflective

practitioner concepts and action research.

Reflective practice

Taylor (2000:3) defines reflection as the throwing back of thoughts and memories, in cognitive

acts such as thinking, contemplation, meditation

and any other form of attentive consideration,

in order to make sense of them and to make

contextually appropriate changes if they are

required. Schn (1983) emphasised the idea

that reflection is a way in which professionals

can bridge the theorypractice gap, based on

the potential of reflection to uncover knowledge in and on action. He referred to tacit

knowledge, or knowing in action, as the kind of

knowledge of which practitioners may not be

entirely aware. When practitioners/clinicians,

such as nurses, are coached to make explicit

their knowing-in-action, they can inevitably use

this awareness to enliven and change their practice (Schn 1987).

Nursing has applied reflective practice ideas

to many of its disciplinary areas. In particular,

nursing has used reflective processes for some

time, for example, to improve practice and

practice development (Johns 2003; Stickley &

Freshwater 2002;Thorpe & Barsky 2001;Taylor

2000, 2002a,b), clinical supervision (Gilbert

2001; Heath & Freshwater 2000;Todd & Fresh-

ACCESSING PARTICIPANTS

Ethical implications

Full ethical clearance from the University and

the Health Campus Research Committee preceded the commencement of the project. As

this research encouraged nurses to share their

practice stories, likely risks were that the privacy and confidentiality of patients may have been

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

CN

237

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

CN

Beverley Taylor et al.

breached and that nurses may have felt vulnerable in sharing their experiences, leading to

embarrassment or possible emotional catharsis,

such as tearfulness or anger. No group member

became emotionally upset beyond the ability of

the group to support them and. although the

project offered professional counselling at no

cost to self, no participant required this service.

Nurses are educated in the need for patient

confidentiality and they practice it daily in their

work. Even so, the researcher ensured that privacy and confidentiality measures were instituted and maintained. Stories written in journals

and shared in group meetings were devoid of

information which could identify patients, relatives and staff. Pseudonyms were used and identifying material was omitted or renamed to

protect the identities of people within the written transcripts of the stories. Reflective journals

remained the personal property of participants

and they were not be read or sighted by the

researcher unless it was a participants expressed

wish that this occurred. Reports and published

material describe the participants stories and

interpretations, according to the issues they

raised and the practice improvements they

caused, rather than to identify specific people,

places and situations.

Participant recruitment

A verbal and written explanation of the project

was given by the researcher at a regular meeting

of the Registered Nurses (RNs) working at the

hospital. Convenience sampling was used to target intentionally RNs interested in reflecting on

their practice in order to improve it. Four RNs

agreed to participate: three females and one

male, from 30 to 45 years of age, with from 10

to 15 years of clinical nursing experience.

The sequence of research activities was based

on previous projects (Taylor 2001a,b).The data

collection activities were embedded in the

group processes and they were that:

RNs were given opportunities to write journal reflections of practice experiences, by

using participant observation during the normal course of their work in ward areas. As

with all nursing care, the details of patients

care were completely confidential.

the reflections were shared in the group

meetings.

the individual and the group critically

analysed the content of all the shared practice

stories and identified common themes and

issues in nursing practice (Taylor 2000).This

means that the participants collectively discussed issues raised in the stories, decided on

the specific nature of issues and named those

issues as research themes.

a theme common to all of the reflections was

identified as the thematic concern (issue) as a

focus for the group. The thematic concern

was the need for assertion in workplace communication.

an action cycle of planning, assessing, observing and reflecting generated an action plan

for addressing and amending the identified

thematic concern.

the action plan was instituted in nursing

practice and the results of the changed

approach to the thematic concern were

noted, through continued planning, acting,

observing and reflecting.

the action plan underwent revision until it

achieved positive changes in successfully

managing the identified thematic concern of

assertion in nursing practice.

RESEARCH PHASES

Data collection and analysis

The research period occurred in five main

Over a 17-week period, the four RNs met phases:

weekly with the researcher/facilitator for one introductory processes;

hour to discuss clinical problems raised by them reflections on practice stories;

in their journal writing and group discussion. locating a thematic concern;

238

CN

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

Assertiveness in nursing practice

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

generating, applying and revising the action

plan; and

improving assertion through reflective practice.

Phase One: Introductory processes

The introductory processes were from the first

to third meeting inclusive. In the first meeting,

each participant received a folder containing

documents relating to the research. Participants

read the Plain Language Statement about the

research and signed the Consent Form. Participants began talking about themselves, especially

where they work and what they hoped to

achieve from the research.The researcher/facilitator gave a brief introduction to the main ideas

within action research and reflective practice

and how the two combine well for research

into nursing practice. Participants discussed the

group processes and agreed that they would like

to be uninterrupted when telling a story, and

expressed the wish for confidentiality in the

group to be maintained to develop trust in the

group and to encourage disclosure. Participants

decided to meet weekly at the same day and

time and to use videoconferencing sometimes,

to reduce the researcher/facilitators road travel.

The second meeting was by videoconferencing and each participant spoke informally about

their week and how they were feeling generally.

This became an informal check-in icebreaker

each week. Participants were concerned about

having relatively little knowledge of research so

they were assured that the process would be

instructive in collaborative research processes.

Participants were asked to reflect on the following questions: Who influenced my childhood

(people, organisations, etc)? What rules for living did I learn? How have these rules for living

influenced my nursing practice? Participants

responded spontaneously to these questions and

they agreed to reflect on these questions during

the week.

In the third meeting, it was reiterated that no

persons name would appear in research reports

CN

of publications and that the use of a split pronoun approach (s/he) to writing would hide

the identity of the only male in the group. Participants read the Agendas and Minutes of the

previous meetings and noted handouts on Some

Background on Research and Reflection, and

the first reflective task of reflecting on childhood influences. Participants shared some of

their thoughts on the introductory reflecting

task. For example: A participant recognised personal difficulty in facing anger, relating to a

work situation in which confrontation of an

aggressive colleague was needed. The participant tried to secure a winwin situation and

remarked that it was important to be assertive

in the situation, especially in light of how nurses

might be perceived by other members of the

multidisciplinary team. It was noted that disciplines have different ways of communicating

and that it is far easier to talk with nurse colleagues than it is with other professionals, such

as teachers.

Phase Two: Reflections on practice

stories

The second phase of reflecting on practice stories was from the fourth to seventh meeting

inclusive. In the fourth meeting, participants

began sharing their practice stories. For example, a participant shared a story of being called

urgently to a medical ward by some nurses and

s/he did not know why, but guessed it related

to a clinical situation.When s/he arrived, there

was a young male patient in distress,in a dreadful situation. He was clammy, pale and had a

tracheostomy. S/he assessed that the mucous

coming copiously through his mouth and tracheostomy tube was indicative of pulmonary

oedema. At first s/he thought: What am I

doing here? I dont know what to do, but the

old ICU nurse kicked in and s/he took control

of the situation and organised the emergency

care and medical assistance. Since that time,

s/he has used that scenario to highlight the

case in the hospital, but s/he has felt powerless

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

CN

239

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

CN

Beverley Taylor et al.

to cause changes as some people have a strangle

hold on the decisions. S/he also commented

that s/he was careful not to blame the nurses in

the situation, but wondered why they were trying to hide their lack of knowledge of what to

do and whether they were scared of getting

into trouble for doing something wrong, even

though they had done nothing wrong.

This led to a conversation of how nurses are

in life/death situations with so much to know in

order to act quickly to be effective clinically.

The researcher/facilitator suggested that the

participant who shared the story raise as many

questions as s/he can about the situation and

personal responses to it, but to leave the questions open-ended and unanswered. Another participant commented that, especially at acute

ward level, nurses are quick to notice other

nurses mistakes but do not tend to give praise

to one another.

In the fifth meeting, participants spoke

briefly about some reflections on the story of

the acutely ill male patient with pulmonary

oedema and other questions that might be asked

about the story. Participants continued sharing

their practice stories. A practice story related to

a busy shift in ICU, when a child with acute

leukaemia was admitted.The participant told of

the terror that s/he feels when a sick child

comes in, relating the sense of responsibility it

creates. The participant was relieved when the

childs care was allocated to a senior nurse who

s/he felt could handle it when the child needed a platelet transfusion. The participant

expressed the need s/he felt to check on the

infusion procedure for platelets, sensing that the

nurse may not have been aware of how to do the

task properly. The information was not in the

ward so s/he went to locate it elsewhere. The

platelets had come from hundreds of kilometres

away, the childs parents were there, the ICU

was fairly silent, the platelets were not going

through and the participant feared the platelets

would soon be coagulating. As the nurse in

charge of that shift, the participant took control

240

CN

of the situation by quietly suggesting to the

nurse that s/he get another filter, while the participant gently moved the platelets in the transfusion bag to minimise coagulation. The

participant expressed feelings of increasing

stress, especially as the parents asked if anything

was wrong, and s/he covered up by replying

that it was a faulty filter. The after hours NUM

was contacted by phone and s/he was not

impressed having to find another filter and

asked why it was necessary. The participant

could not speak out loud on the phone as the

ward was quiet and the parents were listening.

The participant thought: Why couldnt she (the

nurse caring for the child) admit she didnt

know (how to prepare the filter)? What do the

parents think? After the story the participant

asked herself: Why do I take so much responsibility for others? The participant felt so

annoyed at the nurse for not speaking up and

admitting that she did not know how to prepare

the filter, as it would have saved so much time,

energy and worry.

A participant commented that nursing is a

job in which nurses are under scrutiny and

pressure.The researcher/facilitator guided the

storytelling participant through questions as

prompts to get to a deeper level of reflection on

the incident. Where do my ideas come from historically? In other words, what are the values you hold

about nursing practice and from where do your values

come? The participant expressed a belief in the

need for quality care, and for maintaining a professional image of nursing. In the past, s/he has

seen things done badly, incorrectly and s/he

imagined what it might be like to be in the

same predicament. What do I continue to use these

values in my work? Its just me I just want a

good outcome. Whose interests do these values

serve? In other words, who benefits? Me and the

broader image of nursing I guess Im modelling the image (I want for nursing). What power

relations were involved in the story? This nurse is

close to (someone in authority). The participant realised s/he stayed quiet in not asking the

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

Assertiveness in nursing practice

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

nurse in the story if she knew the correct procedure for the filter, because of implicit power

relations, even though the participant was in

charge of the shift and s/he felt it reflected

badly on her/his ability to handle the shift.

In the sixth and seventh meetings, participants continued to share practice stories and to

work through deeper levels of reflection and

meaning by posing questions to themselves

about their personal and professional values and

interests.

Phase Three: Locating a thematic

concern

Phase Three lasted from meetings eight to 11

inclusive. After many practice stories were

shared in the second phase, it was time to locate

a common interest on which all of the participants could reflect and use an action research

approach to explore more deeply. In the eight

and ninth meeting, participants examined a

Table of practice stories to locate issues and

themes within them. Participants discussed

issues and interests that arose: for example,

their reactions to suicide of clients and acquaintances, the relative usefulness of being under

scrutiny and pressure in nursing work, the inexplicability of nurses intuition, and the role of

consumer representatives in bringing about policy changes.

In the tenth meeting, participants listed the

issues/themes generated in the group as: assertion/confrontation/conformity; bullying and

horizontal violence; Aboriginal issues; professional protection of self and others; professional

competency of self and others; slow change;

having a sense of belonging; being under scrutiny and pressure, documentation issues; self

blame and perfection; autonomy versus duty of

care; and role clarification/role valuing.

In the next meeting (11), participants agreed

that they would work as a whole group and

needed to find a thematic concern that was sufficiently generic to their practice so that they

could all see improvements in that area. After

CN

much fruitful discussion, the group decided that

the area most common to them all, with the

best chance of creating practice improvements,

was the thematic concern of assertion/confrontation/conformity. As participants had not

checked their understanding of what each person meant by assertion, they defined it individually so that the group had a working definition.

The responses were that assertion is about:

Participant 1: valuing others opinions while

giving ones own opinion, and not being

scared to do so.

Participant 2: not being passive but not being

aggressive, so there is balance and a middle

ground. It is me challenging myself. I prepare

myself emotionally and usually say: I feel that

...,I would prefer that ...

Participant 3: being at a similar level to make eye

contact, not towering over or being towered

over; with attention to appropriate use of personal space. It involves having an internal conversation to make sense of the concern and to

get it out in the right way. It involves honesty

in what I am saying and feeling, and having self

respect and self esteem, to not let people tread

all over me.

Participant 4: an issue of equality, of feeling valued and of feeling I have an opinion worth

telling others, and having them listen. It reflects

confidence, and the need to let go of emotions,

to find a common ground.

In discussion, participants noted that assertion is

context-specific, in that it depends on the situation as to how nurses react and find voice at

that time. Participants spoke of trying to learn

to listen, taking extra breaths before speaking

and not making preconceived conclusions to

assist assertive communication. We needed to

take a two-week break from meetings so participants agreed to do some homework reflecting

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

CN

241

CN

Beverley Taylor et al.

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

on what is useful and not useful about assertion,

and on practice scenarios when they were

assertive and it went well, and when assertive

attempts did not go well.

ing the previous week at work. For example, a

participant said that s/he experienced an effective assertive episode when s/he confronted a

staff member who used to undermine her.

S/he pulled her aside quietly and privately

told her how s/he felt. The person hearing the

message received it well and expressed surprise

that she had that effect on the participant.

Things have been great since. The participant

reflected that s/he had rehearsed the scenario

and that s/he was pleased it went well.This discussion led to the insight that nurses need not

only to maintain basic courtesies in assertive

attempts, they must also maintain their self

respect and to remind themselves that they are

worthy as nurses and people. Following discussion, the action plan was amended to the second

and final version.

Phase Four: Generating, applying

and revising an action plan

Phase Four lasted from meeting 12 to 14 inclusive. In meeting 12, the group noted that they

often have opportunities in their work to assert

themselves by confronting issues as they occur,

thereby choosing to avoid conformity and not

speaking up. They discussed their reflections

about what is useful and not so useful about

assertion by reflecting on practice situations. As

each person spoke, other participants responded and encouraged openness in a trusting group

process.

For example, a participant said that s/he has

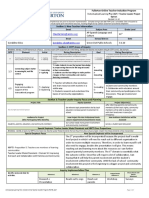

been giving the matter a lot of thought and had ACTION PLAN: Strategies for

realised that assertion is the initiation tool to improving assertion at work

get things started as it is the starting point of 1. Ask: What are the real issues? What do I

collaboration within the multidisciplinary team.

need to communicate effectively?

If the timing is not right, assertion loses its 2. Bring energy to the job. Dont go to work

impact. If the timing of assertion is wrong, the

tired, or sick, or with personal issues getassertive attempt comes off the wrong way.

ting in the way that is, be feeling OK

Courage and timing are needed to get assertive

when you go to work, to give it your full

attempts just right so they have maximal impact.

attention.

This point led to further comments by other 3. Get your emotions under control that is,

group members, such as: In the consultation

be aware of your bodily responses to

role, timing is important ... it is important not

assertive opportunities, such as to note

to patronise. Experienced health care staff

your heart rate is telling you it is important

already have considerable communicative skills,

to speak, wait your turn, and then speak.

and poorly timed or initiated attempts to assert 4. Get the facts ready dont go off halfmay be interpreted as patronising.

cocked.

The group then moved onto the next part of 5. Find a good place to talk if possible, for

the process which was to brainstorm ideas for

example, not on the move and walking in a

strategies for making assertion more effective.

busy and noisy setting. Suggest a time to

Given that brainstorming allows all ideas to be

talk and go aside into a quiet environment.

heard and noted, the original list was unedited 6. If an ideal time and place is not possible for

and it contained some accompanying discussion

effective communication, gauge the responthat arose at the time the ideas were shared.

siveness of the other person and decide

In meeting 13, discussion continued about

whether to speak up at that time, or to wait

the pros and cons of assertion and whether the

until a more conducive moment.

action plan had been helpful to participants dur- 7. Timing is important, so it may be better to

242

CN

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

Assertiveness in nursing practice

wait to communicate an assertive position.

For example, in professional group meetings when issues arise, it may be better to

wait, recognising the limitations of the context.

8. Effective assertion requires a listener. The

person to whom you are communicating

needs to know who you are and why they

should listen to you. Introduce yourself and

make sure the person knows who you are,

how you fit into the scheme of things, and

how you have the capacity to represent

clients needs and issues.

9. Recognise the communication style of the

other person, as little may be achieved if

there is aggression and firmly held misconceptions.

10. When meeting with other people who are

not in your immediate disciplinary group,

to minimise misinterpretations based on

lack of understanding of roles and intentions, sit down and begin by asking people

about their priorities, specifically what they

hope to achieve in the meeting that is,

their objectives before conveying your

own. In this way, it is possible to clarify

intentions and expectations, and to see if

objectives match, and thereby ascertain the

angle people are coming from.

11. Be prepared to go it alone without backup

and support, when asserting a position.

12. Maintain basic courtesies, such as conveying

respect, by addressing the person by name

and title.

13. Maintain your self-respect and remind

yourself that you are worthy as a nurse and

person.

14. Remember that communication has many

modes such as face-to-face, emails, letters,

phone calls, etc, and that all of these communication modes are important opportunities for assertion.

15. Use ongoing reflection and educational opportunities to further develop knowledge

and skills in assertion.

CN

By meeting 14, participants were well into the

action research part of the project because they

were actively enlisting the action plan and refining it through practice reflections. For example,

a participant told of a situation involving a student who had been at the hospital for 10 days of

clinical placement and wanted the participant to

write a report on her abilities.The student was

looking pleadingly at the participant. In this

case, the participant asserted that s/he could

not in all fairness write a report based on one

day of observation of her practice, so s/he

referred her to another staff member in a better

position to comment.The participant said that,

at work, s/he was aware of the groups research

discussions and the action plan, and s/he kept

thinking:Assertion!

Phase Five: Improving assertion

through reflective practice

In the last phase from meetings 15 to 17 inclusive, participants continued to share practice

stories and insights related to assertiveness. For

example, a participant shared a practice story of

how s/he applied some principles learned in a

Tai Chi workshop to a clinical situation, specifically to become ready for assertiveness. For

example, a young female patient was in need of

a stay in a clinical support unit before being

allocated support accommodation. Frequent

previous attempts to secure the admission to the

clinical unit had been unsuccessful because of a

huge waiting list. The participant phoned the

doctor and, in a relaxed manner, laid out the

situation and put it in terms of pressure of

beds, and as advantages for the young female

and also for the unit. S/he emphasised

improved outcomes and was successful in securing short-term admission that day, to her/his

amazement. When the group discussed the

story, they focussed on tone of voice on the

phone when transmitting an assertive message.

The relaxed tone was because the participant

thought the situation was hopeless so there was

nothing to lose by another plea. Participants

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

CN

243

CN

Beverley Taylor et al.

see no benefit from doing research I did

not have the experience or maybe I was too

lazy It was so timely when I heard it

was action research action and research! I

thought: That sounds good! I have had experiences and I have something to say. The

meetings have all been valuable I now

have a different spin on research and academic. This research can help my practice. I can

see what I have learned here and I have put it

into practice. I had only known about medical model research and it seemed too long.

This action research is perfect for me,

because of doing it (researching) in a group.

agreed that if they are too earnest in their

requests, the voice can become crackly and does

not sound assertive. In addition, a participant

noted that if s/he is out of breath, confidence

decreases.

The last meeting (17) was by teleconference

and the group shared practice stories and

insights. Finally, the participants shared their

experiences of being involved in the action

research and reflection project, and their

responses were:

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

I found the process interesting especially

in how to go about research ... the steps

involved. I found that I have a lot of stuff

buried inside I remembered practice stories from long ago and they are still stirring

up so much, that is surprising I need to

deal with it (the practice experiences) I

enjoyed talking at a deep level. I can see my

work experiences are full of opportunities

for research. I enjoyed the team work and the

friendship, trust and disclosure. (The participant talks regularly with a critical friend, to

aid reflections on his/her practice.)

I really enjoyed the process. I was surprised

by how I got into the reflection and I continued writing personal reflections. I did a lot of

personal journaling at home and (a family

member) enjoyed the insights into my life

s/he did not know before.When I put pen to

paper I was amazed at how the details came

flooding back the smells, emotions, feelings. It made me sit back and reflect about

work being (myself) I put my head down

and got on with things. I tend to be a happy

person and to dwell on things being

reflective is a positive way of dwelling on

things I enjoyed researching with three

other experienced nurses and fitting in

with the others (participants) and areas of

conversations.

The most valuable aspects of the research for

me has been the focus on practice reflection.

I have used reflective journalling previously

and always found it a useful tool, but in the

day-to-day business I have been forgetting to

incorporate reflection into my self-care. My

wish is for all nurses to give reflective journalling a go at least once, particularly the

analysis of the reflections. The research has

reminded me to reintroduce reflection more

regularly into my practice. The cohesive

group we formed during the research process has been a highlight for me. At all times I

felt safe to disclose my thoughts and the

members discussion and comments have

been both insightful and comforting. I believe

the project has fostered the formation of new

nursing bonds that can only be good for our

profession.

The researcher/facilitator thanked the group

for their comments and suggested that they now

had the knowledge and skills to undertake

action research themselves, whenever they had

practice issues that need deeper attention.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

The implications of the research are that action

research and reflection are practical research

I am very practically minded and value com- processes for nurses to examine their practice

monsense I am not academic and could issues and to improve nursing care. The action

244

CN

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

Assertiveness in nursing practice

research and reflective practice approach can be

used in a variety of ways to assist nurses to

reflect on practice issues and care improvements. This project shed light on the need for

assertiveness and ways in which to improve

assertiveness at work.

The nurses in this research generated an

action plan with practical strategies for improving assertiveness at work. The action plan is

available to other nurses who may find it useful

in improving their assertiveness at work. The

implications of this research for nurse teachers

are that assertiveness continues to be a difficult

skill to enact in the immediacy of the workplace. The communication skills within the

action plan from this research can be explored

in experiential teaching sessions.

In conclusion, the nurses in this research

realised that assertiveness is difficult, but that it

is possible when a reflective approach is taken

to practice.The implication of this research for

other nurses with whom it resonates is that they

too can make positive changes to their assertiveness, by paying focused attention to their daily

work practices.

References

Addis J and Gamble C (2004) Assertive outreach

nurses experience of engagement. Journal of

Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 11(4):

452460.

Anderson M and Branch M (2000) Storytelling: A

tool to promote critical reflection in the RN

student. Minority Nurse Newsletter (71): 12.

Benner P (1984) From novice to expert: uncovering the

knowledge embedded in clinical practice. AddisonWesley, Menlo Park CA.

Benner P and Wrubel J (1989) The Primacy Of

Caring: Stress And Coping In Health And Illness

Addison-Wesley, Menlo Park CA.

Benton D (1999) Assertiveness, power and

influence. Nursing Standard, 13(52): 4852.

Cardillo D (2003) Become more assertive, one

step at a time. Nursing Spectrum 4(8): 17.

Chenoweth L and Kilstoff K (1998) Facilitating

CN

positive changes in community dementia

management through participatory action

research. International Journal of Nursing Practice

4: 175188.

Class P (2001) Assertiveness for dummies. Nursing

Spectrum 14(10): 3.

Clegg S (2000) Knowing through reflective

practice in higher education. Education Action

Research 8(3): 451469

Crouch D (2003) Careers. How to be assertive,

Nursing Times 99(40): 7071.

Cruickshank D (1996) The art of reflection:

using drawing to uncover knowledge

development in student nurses. Nurse Education

Today 16(2): 12730.

Dick RA (1995) A beginners guide to action

research. ARCS Newsletter 1(1): 59.

Floyd K (1999) Career fitness: Assertiveness made

simple. Nursing Spectrum 12(3): 15.

Floyd K (2001) Be assertive and true to

yourself. Nursing Spectrum 11(1): 34.

Freshwater D (1998) From acorn to oak tree: a

neoplatonic perspective of reflection and caring.

Australian Journal of Holistic Nursing 5(2): 1419.

Freshwater D (1999) Communicating with self

through caring:The student nurses experience

of reflective practice. International Journal of

Human Caring 3(3): 2833.

Freshwater D (ed) (2002) Therapeutic Nursing:

Improving Patient Care Through Reflection Sage,

London.

Gaddis S (2004) The power of positive nursing.

Pulse 41(4): 1314.

Gilbert T (2001) Reflective practice and supervision: meticulous rituals of the confessional.

Journal of Advanced Nursing 36(2): 199205.

Glaze J (1999) Reflection, clinical judgement and

staff development. British Journal of Theatre

Nursing 9(1): 3034.

Habel M (2004) Staying cool under fire: how well

do you communicate? NurseWeek, September.

Heath H (1998a) Keeping a reflective practice

diary: a practical guide, Nurse Education Today

18(7): 592598.

Heath H (1998b) Reflection and patterns of

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

CN

245

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

CN

Beverley Taylor et al.

knowing in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing

27(5): 10541059.

Heath H and Freshwater D (2000) Clinical

supervision as an emancipatory process:

Avoiding inappropriate intent. Journal of

Advanced Nursing 32(5): 12981306.

Holmes C (1992) The drama of nursing. Journal of

Advanced Nursing (17): 954960.

Jaime S, Ortiz R and Vazquez P (1998)

Assertiveness in nursing: A characteristic of the

profession? Enfermeria Clinica 8(3): 98103.

Johns C (2000) Working with Alice: A reflection.

Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery

6: 199303.

Johns C (2003) Easing into the light. International

Journal for Human Caring 7(1): 4955.

Keatinge D, Scarfe C, Bellchambers H, McGee J,

Oakham R, Probert C, Stewart L and Stokes J

(2000) The manifestation and nursing management of agitation in institutionalised residents

with dementia. International Journal of Nursing

Practice 6: 1625.

Kemmis S and McTaggart R (eds) (1988) The

Action Research Planner Deakin University Press,

Geelong,Victoria.

Kim HS (1999) Critical reflective inquiry for

knowledge development in nursing practice.

Journal of Advanced Nursing (295): 12051212.

Koch T, Kralik D and Kelly S (2000) We just dont

talk about it: Men living with urinary

incontinence and multiple sclerosis. International Journal of Nursing Practice 6: 253260.

Kupperschmidt B (1994) Carefronting: caring

enough to confront. Oklahoma Nurse 39(4): 710.

Larson B (1997) Communication. Assertiveness,

Home Health Focus 4(4): 28.

Levesque J (2003) Nurses must be assertive. AACN

News 20(1): 2.

Lyttle V (2001) Why ED nurses have that attitude.

RN (reprinted by permission) Summer, 1618.

Madden P (1996) Onwards with new

assertiveness. World of Irish Nursing 4(3): 5.

McCabe C and Timmins F (2003) Teaching assertiveness to undergraduate nursing students.

Nurse Education in Practice 3(1): 3042.

246

CN

McCartan P and Hargie O (2004a) Assertiveness

and caring: Are they compatible? Issues in

Clinical Nursing 13: 707713.

McCartan P and Hargie O (2004b) Effects of

nurses sex-role orientation on positive and

negative assertion. Nursing and Health Sciences

6(1): 4549.

McNally S (2002) If nursings profile is to be

raised, it must be assertive. British Journal of

Nursing 11(17): 1114.

Milstead J (1996) Basic tools for the orthopaedic

staff nurse. Part 1: assertiveness. Orthopaedic

Nursing 15(1): 2330.

Morris R (2004) Speak up or shut up?

Accountability and the student nurse. Paediatric

Nursing 16(6): 2022.

Pacquiao D (2000) Impression management: an

alternative to assertiveness in intercultural

communication. Journal of Transcultural Nursing

11(1): 56.

Pauly-ONeill S (1997) Warning: being gutsy can

be habit-forming. Missouri Nurse 66(2): 16.

Pearce C (2004) Being assertive in the workplace.

Nursing Times 100(21): 4647.

Percival J (2000) Say what you want. Nursing

Standard 15(5): 25.

Percival J (2001) Dont be too nice. Nursing

Standard 15(19): 22.

Percival J (2005) Be clear and firm. Nursing

Standard 19(23): 26.

Platzer H, Blake D and Ashford D (2000a) Barriers

to learning from reflection:A study of the use of

groupwork with post-registration nurses. Journal

of Advanced Nursing 31(5): 10011008.

Platzer H, Blake D and Ashford D (2000b) An

evaluation of process and outcomes from

learning through reflective practice groups on a

post-registration nursing course. Journal of

Advanced Nursing 31(3): 689695.

Schn DA (1983) The reflective practitioner: how

practitioners think in action Basic Books, NY.

Schn DA (1987) Educating the reflective practitioner

Jossey-Bass, London.

Smith L (1997) Collaboration: the key to assertive

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

Downloaded by [University of Otago] at 20:48 20 July 2015

Assertiveness in nursing practice

communications. MEDSURG Nursing 6(6):

373377.

Stein-Parbury J (2005) Patient and Person:

Interpersonal Skills in Nursing Elsevier, Sydney.

Stickley T and Freshwater D (2002) The art of

loving and the therapeutic relationship. Nursing

Inquiry 9(4): 250256.

Stringer ET (1996) Action research:A Handbook for

Practitioners Sage,Thousand Oaks CA.

Taylor B (1997) Big battles for small gains:A cautionary note for teaching reflective processes in

nursing and midwifery. Nursing Inquiry 4: 1926.

Taylor B (2000) Reflective practice for nurses and

midwives:A practical guide Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

Taylor B (2001a) Overcoming obstacles in

becoming a reflective nurse and person.

Contemporary Nurse 11(23): 187194.

Taylor B (2001b) Identifying and transforming

dysfunctional nursenurse relationships through

reflective practice and action research. International Journal of Nursing Practice 7(6): 406413.

Taylor B (2002a) Technical reflection for

improving nursing and midwifery procedures

using critical thinking in evidence based

practice. Contemporary Nurse 13(23): 281287.

Taylor B (2002b) Becoming a reflective nurse or

midwife: using complementary therapies while

CN

practising holistically. Complementary Therapies

in Nursing and Midwifery 8(4): 6268.

Taylor B (2003) Emancipatory reflective practice

for overcoming complexities and constraints in

holistic health care. Sacred Space 4(2): 4045.

Taylor B (2004) Technical, practical and emancipatory reflection for practising holistically. Journal

of Holistic Nursing 22(1): 7384.

Taylor B, Bulmer B, Hill L, Luxford C, McFarlane

J and Stirling K (2002) Exploring idealism in

palliative nursing care through reflective

practice and action research. International

Journal of Palliative Nursing 8(7): 324330.

Thorpe K and Barsky J (2001) Healing through

self-reflection. Journal of Advanced Nursing

35(5): 760768.

Timmins F and McCabe C (2005) How assertive

are nurses in the workplace? A preliminary pilot

study. Journal of Nursing Management 13(1): 6167.

Todd G and Freshwater D (1999) Reflective practice and guided discovery: Clinical supervision.

British Journal of Nursing 8(20): 13831389.

Wilkin K (2002) Exploring expert practice

through reflection. Nursing in Critical Care 7(2):

8893.

Woods R (2003) Healthy boundaries=healthy

nurse:The foundation of assertive living and

working. Nursing matters 14(12): 16, 1819.

ANNOUNCING

HEALTH SOCIOLOGY REVIEW

S OCIAL E QUITY

AND

H EALTH

Edited by Olle Lundberg, CHESS, Karolinska Institute, Sweden

ISBN 0-9757422-8-0; iv + 124 pages; softcover

Details at: http://hsre-contentmanagement.com/15.2/social-equity-and-health.htm

Course Coordinators are invited to contact the Publisher:

subscriptions@e-contentmanagement.com for an adoption evaluation copy.

Volume 20, Issue 2, December 2005

CN

247

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Curriculum de Hong-Kong - Ed. B - Sica-MatematicaDocumento292 páginasCurriculum de Hong-Kong - Ed. B - Sica-MatematicaGregório Silva NetoAinda não há avaliações

- Ilp FullertonDocumento3 páginasIlp Fullertonapi-467608657Ainda não há avaliações

- Muluken Alemayehu FINAL PDFDocumento47 páginasMuluken Alemayehu FINAL PDFKefi BelayAinda não há avaliações

- Plmun Thesis Mike MahorDocumento36 páginasPlmun Thesis Mike MahorPAUL DANIEL MAHORAinda não há avaliações

- Annals of Medicine and Surgery: Bliss J. ChangDocumento2 páginasAnnals of Medicine and Surgery: Bliss J. ChangroromutiaraAinda não há avaliações

- Rti 2Documento10 páginasRti 2REG.B/0620103018/LUQMAN AHMADAinda não há avaliações

- Perceived Benefits Received and Behavioral Intentions of Kabankalan Sinulog Festival TouristsDocumento14 páginasPerceived Benefits Received and Behavioral Intentions of Kabankalan Sinulog Festival TouristsMark GermanAinda não há avaliações

- Blood Drive ProposalDocumento4 páginasBlood Drive Proposalapi-250853393100% (2)

- HDFC Bank Project Saving AccountDocumento58 páginasHDFC Bank Project Saving Accountkunal srivastava100% (6)

- Step by Step Approach For Qualitative Data Analysis: Babatunde Femi AkinyodeDocumento12 páginasStep by Step Approach For Qualitative Data Analysis: Babatunde Femi AkinyodeSarras InfoAinda não há avaliações

- Adminstrative LawDocumento27 páginasAdminstrative LawGuru PrashannaAinda não há avaliações

- ACTION RESEARCH PRoposalDocumento2 páginasACTION RESEARCH PRoposalFritzAinda não há avaliações

- IELTS Vocabulary (1) JDocumento7 páginasIELTS Vocabulary (1) JBolorAinda não há avaliações

- ResumeDocumento1 páginaResumeapi-289204640Ainda não há avaliações

- O 1 Request PacketDocumento18 páginasO 1 Request PacketcdolekAinda não há avaliações

- UNICEF Childhood Disability in MalaysiaDocumento140 páginasUNICEF Childhood Disability in Malaysiaying reenAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 2: Data Collection and Sampling Techniques: Activating Prior KnowledgeDocumento12 páginasUnit 2: Data Collection and Sampling Techniques: Activating Prior KnowledgeMaricel ViloriaAinda não há avaliações

- (Cernea, 1995) Social Integration and Population DisplacementDocumento32 páginas(Cernea, 1995) Social Integration and Population DisplacementChica con cara de gatoAinda não há avaliações

- Module 2Documento6 páginasModule 2Christian DelfinAinda não há avaliações

- Shanthini InternDocumento25 páginasShanthini InternJayalakshmi RavichandranAinda não há avaliações

- Household Emergency Preparedness A Literature Review2012Journal of Community HealthDocumento9 páginasHousehold Emergency Preparedness A Literature Review2012Journal of Community HealthAyuAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Running Head: Nursing Theory AnalysisDocumento16 páginas1 Running Head: Nursing Theory AnalysisMa.Therese GarganianAinda não há avaliações

- NCM 116 SyllabusDocumento42 páginasNCM 116 SyllabusMiller Acompañado100% (8)

- Chanakya National Law University: Public International Law On The TopicDocumento4 páginasChanakya National Law University: Public International Law On The TopicKaran Singh RautelaAinda não há avaliações

- RRL DocumentDocumento16 páginasRRL DocumentTito CadeliñaAinda não há avaliações

- 提高创意写作的秘诀Documento13 páginas提高创意写作的秘诀afoddokhvhtldv100% (1)

- Summer Internship Project: ON Performance Appraisal Effectiveness IN Hindalco Flat Rolled Product, HirakudDocumento92 páginasSummer Internship Project: ON Performance Appraisal Effectiveness IN Hindalco Flat Rolled Product, HirakudUmrah NaushadAinda não há avaliações

- Mis CRMDocumento2 páginasMis CRMsolaiman93Ainda não há avaliações

- How To Write A Learning Contract PDFDocumento6 páginasHow To Write A Learning Contract PDFCustom Writing ServicesAinda não há avaliações

- 2014 15 GraduateDocumento306 páginas2014 15 GraduateyukmAinda não há avaliações