Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A Seldom Used Parameter in Pottery Stud

Enviado por

o_djuraDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Seldom Used Parameter in Pottery Stud

Enviado por

o_djuraDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A SELDOM USED PARAMETER IN POTTERY STUDIES:

THE CAPACITY OF POTTERY VESSELS

Jean-Paul Thalmann*

The state of the art in the field of pottery studies has

nowadays reached an unprecedented degree of

sophistication. Not only can the slightiest typological/chronological variation be tracked down through

a host of statistical procedures, but most details of

manufacture, provenience and distribution come

under close scrutiny through physical, chemical or

petrographical analysis. It seems that the modern

archaeologist is now able to acquire and publish any

kind of information about her or his pots except, in

most cases, the quantity of goods, whatever they

may have been, which these pots were intended to

process, store or carry in Antiquity.

This parameter the capacity of a pottery vessel

is however of paramount importance to understand its function, as much as peculiarities in shape

(flat or rounded bottom, wide or restricted opening,

presence or absence of handles etc.). For individual

items, it will in most cases allow to decide between

collective or individual use, short or long-term storage, the possibility of easily moving or carrying

them when full for commercial purposes. In the case

of full sets or assemblages of pottery, it is probably

the safest test for specialization of pottery production and procedures of control over storage or longdistance trade.

Such observations do not reach very far beyond

common sense and many scholars have also stressed

the potential of the capacity of pottery vessels as a

measure of the social and economic characteristics

and even of demographic trends in the populations

which produce and use them, as was conveniently

summarized in a recent article by R.T. SCHAUB

(1996, with relevant references), which awakened an

old interest of mine for this topic. More generally,

considering the wealth of informations which they

Universit de Paris 1 - Mission franaise de Tell Arqa (Liban)

are liable to provide, it is most surprising that functional typologies are so seldom used (SCHAUB 1996:

231235).

CALCULATING

THE CAPACITY OF POTTERY VESSELS

I have found in recent literature very few studies concerned with such problems. In addition to the pottery studies from Bab edh-Dhra (SCHAUB 1987: 249;

1996), the most systematic one is probably the study

by M. ROAF (1989) of the Ubaid burnt house at

Tell Madhhur in the Hamrin. A full domestic assemblage was retrieved, and all vessels have been plotted

on a plan of the house according to type and capacity (ROAF 1989: 121); but, surprisingly enough, few

conclusions seem to have been derived therefrom. S.

MAZZONI (1994) has measured drinking vessels from

Ebla and A. MAEIR has plotted the capacities of

juglets, jugs and bowls from tomb 1181 at Hazor on

graphs which show some trends towards standardization of the first two types, but none for the latter

(MAEIR 1997: 315317 and note 80 for references to

some other studies of palestinian material).

The reasons for this general lack of interest are

easy to understand:

Although not a rarity, whole or wholly reconstructed vessels, and especially large size jars, are far

less common than sherds, and one must have a fair

quantity of them in order to statistically assess e.g.

trends towards standardization.

Calculating the capacity of a pot from a section

drawing is an operation simple in its principle, but

which requires tedious measurements and calculations.

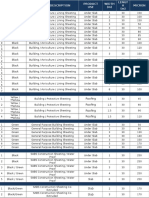

Different methods have been suggested (fig. 1) by

approximating the general shape by means of elementary volumes such as spheres, cones, cylinders

432

Jean-Paul Thalmann

Fig. 1 Different methods for calculating the capacity of pottery vessels

etc. (ERICSON & STICKEL 1973) or of an array of small

cylinders (RICE 1987: 220222). But the former

method is applicable only to very simple shapes.

Moreover, it should be stressed that general approximations are not enough: volumes are a cubic function

of size so that slight variations in diameter or the

flattening of what would be taken for a more or

less spherical body may result in wide differences of

capacity. If we consider an ideal pot with a perfectly spherical body of, say 40 cm in diameter, it has

a capacity of 33,5 litres; the same pot with a diameter of 50 cm will hold 65,5 litres, just twice as much!

It is obvious that estimating capacity classes on the

basis of similar sizes or proportions may result in

wide-ranging errors: accurate measurements are

absolutely needed.

The approximation of the shape by means of

small cylinders is probably accurate enough only

with a very large number of them, which anyway

require too many measurements. It is much easier,

quicker and more accurate to sub-divide the volume

of the pot in a series of truncated cones (Fig. 1). The

calculations for the volume of the truncated cones

are not so straightforward, but, in the age of computers, this should not be a problem. I used at first an

Excel chart, then designed a small standalone computer utility which requires only a few clicks to get

the result (Fig. 2); it is freely available to all colleagues, for Mac and PC computers, on request at my

e-mail address jp.thalmann@wanadoo.fr.

Even when computerized, the procedure is not so

quick, and investigating the capacities and possible

standardization of e.g. MB and LB commercial jars

from available publications will take time. Moreover,

most published drawings of large vessels are at a much

reduced scale, and usually provided with a much too

small graphic scale: it is common for large jars to be

published with a scale of 10 cm only, when the graphic scale on a plate of pottery should be at least the size

of the largest pot represented, in order to allow for

direct measurements. Unavoidable approximations in

re-scaling such improperly published drawings may

result in the kind of errors outlined above. For these

reasons, I shall present here only a few preliminary

results (cf. also THALMANN 2003) obtained using excellent drawings from Tell Arqa (Lebanon) and Tell ed-

Fig 2 Measuring jars from Tell ed-Dabca on the computer

A Seldom Used Parameter in Pottery Studies: the Capacity of Pottery Vessels

433

Fig. 3 Jars from Arqa Phase P (EB IV)

Dabca, in order to illustrate the potential of vessel

capacity in pottery studies.

SOME

OBSERVATIONS ON STORAGE AND COMMERCIAL

CONTAINERS

The excavation of Tell Arqa (North Lebanon), under

the direction of the author (THALMANN 2000; 2002;

forthcoming), has produced a large number of complete or wholly reconstructible pots, mainly from late

EB IV (Phase P) to MB I (Phase N) i.e. from ca. 2200

to 1800 BC, which provide a sound preliminary basis

for further capacity studies. They range from smallsized domestic jars to medium-sized jars probably

intended for short-term storage and transport (most

types have a version without and a version with handles), and finally to very large storage vessels (Fig. 3,

5). When sorted out by capacity, they fall into groups

which correspond only loosely with the main types

designed on the basis of general shape and proportions, but can be interpreted in functional terms and

show an evolution in the production and use of such

vessels from one period to the next.

Jars from Arqa Phase P

The capacity diagram (Fig. 4) shows five distinct

groups, probably related mainly to functional specialization. The distribution of jars with (black and

grey dots) and without handles (white dots) is especially remarkable.

Group 3 is comprised of jars with handles only,

and capacities ranging from 20 to 25, exceptionally

30 litres (Fig. 3: 5). Such jars weighing about 30 kilos

when full would probably not be difficult to carry,

although the position of the handles or the large flat

bases are not well suited for this use. The vertical

handles are attached low on the body, i.e. close to the

center of gravity of the vessel, as is ususal in the Levant during the EB (AMIRAN 1969: 59, 63, 66, 67) and

still at the beginning of the MB period (AMIRAN 1969:

104; ASTON 2002: figs. 14). This makes it easy to

move the jar or to tilt it for pouring when it rests on

the ground, but does not insure verticality when carrying it by hand. Such jars would therefore be better

considered as short-term storage vessels, which for

this reason had to be frequently displaced within the

dwelling area, rather than as transport or commercial containers.

In a significant manner, during MB and LB, handles will be attached higher and higher on the shoulder, well above the center of gravity, and pointed or

stump bases will replace the flat ones. Capacities are

then frequently more important; the jars can be carried in a vertical position by two men or handled for

pouring, using one handle and the stump base, by

434

Jean-Paul Thalmann

Fig. 4 Capacity diagram for Phase P

one. One of the earliest examples of this morphological adaptation of jar handles to the logics of transport, and especially of maritime trade, is to be found

in the group of jars from the Royal Tombs at Byblos

(TUFNELL 1969: fig. 6); their average capacity is 40 to

45 litres, nearly twice as much as the jars of Arqa

group 3.

Groups 4 and 5, with capacities ranging respectively from 55 to 75 and 90 to 120 litres, are clearly

distinct, although the sheer consideration of general

size and proportions, as noted above, would not allow

to set them apart. Because of their weight, all such

jars (Fig. 3: 68) must be non-movable storage vessels, and indeed most of them were found filled with

cereals in both destructions layers of Phase P. The

two groups may correspond to the storage of different kinds of products (liquid/solid) or to different

conditions (middle-range or long-term storage).

Surprisingly, handles are occasionally found on jars

from these groups. A few jars of group 5, all above 100

litres, have a small loop handle from the top of the

shoulder to the rim (Fig. 3: 8): while unpractical to tilt

such large vessels for pouring, the handle would be well

suited to attach with a rope a wooden stopper for

instance, if the jars had to be frequently opened and

closed. For this reason, they could be interpreted as

water containers the type is rare, and one or two such

jars only were necessary in each house.

Some jars of group 4 (grey dots) have vertical

handles, similar in position and shape to those of

group 3 jars (Fig. 3: 6): for reasons given above, they

were certainly very ill-suited for carrying the jars

when full. The group is very homogeneous, characterized by the profiling of the rim, but above all by

the incised and impressed decoration on the upper

part of the body (Fig. 3: 6). They are found at Arqa

from level 16B to level 15A, a period of about two

centuries. With the exception of a few fragments

from sites close to Arqa and a unique fragment from

Byblos (BYBLOS II: 16572), I know of no parallels to

this type of decoration and consider it most probably

the work of one or two families of local potters over

a few generations.

Apart from the possible symbolic connotations of a

part of the decoration (suns or stars and stylized

vegetal elements), the overall pattern seems to be

derived from a practical device of ropes or basketry,

comparable to our modern dames-jeannes. The wide

arches of impressed dots are attached to a row of

similar impressions on the maximum diameter of the

body, to the handles and to small lugs which are otherwise part of the applied decorative elements. It is

impossible to know whether such a system, which

would permit to carry easily the large jars and may

also have been used on their smaller counterparts of

group 3, was actually used in the Levant by the end

of the IIIrd millenium. It is however such a simple

device that the probability is high; it would have been

A Seldom Used Parameter in Pottery Studies: the Capacity of Pottery Vessels

later abandoned with the above-mentioned evolution

of pottery containers specifically adapted to trade.

Representations of such devices, probably on handleless jars only, exist on cylinder-seals at the end

of the Uruk period (e.g. LE BRUN 1978: fig. 8: 5;

LE BRUN and VALLAT 1978: fig. 6: 4, 9, fig. 7: 12), but

I know of no later ones.

Finally, some puzzling questions arise from the

capacity diagram. None of the smaller jars of group

1 (5 to 13 litres, Fig. 3: 1, 2), either because they are

handleless or have too wide and short necks, appear

to be adapted to the carrying of water for daily use.

Everywhere in the Middle East, and especially at

Arqa, where the river flows in a deep gorge at the foot

of the tell some 40 to 50 m below the settlement, this

was a painstaking but important task, for which one

would expect to find specially designed containers. In

the whole assemblage of Phase P, only very large jugs

(9 to 15 litres, triangles on the diagram, Fig. 3: 3, 4),

with restricted neck and trefoil mouth, meet the necessary requirements. They are too large for pouring

water for individual use into the small cups and goblets which are the standard drinking vessels of the

period. But they could be easily carried on the shoulder or on the head, while the restricted neck prevented the spilling out of water. This type is frequent, as

can be expected for vessels with a high probability of

435

breakage, and very many of them were probably

necessary in every single house.

Jars from Arqa Phase N

The capacity diagram for Phase N shows a very different picture (Fig. 6). It is obvious that pottery production is much more specialized and standardized:

only three groups. Jars with (black dots) and without

handles (white dots) are represented in the first (12 to

17 litres) and the second one (20 to 30 litres), while all

larger jars in group 3 (40 to 60 litres) are handleless;

the very large containers with capacities of 90 litres

and more seem to have disappeared. This is probably

in part due to the fact that the Phase N assemblage

is derived from the potters quarter and workshop

(THALMANN 2000: 4750; 2002: 368369), not from an

ordinary dwelling quarter. It is however noteworthy

that, if large jars of about 100 litres were in use elsewhere in the settlement during Phase N, they were

manufactured in a different location and by different

potters; this was certainly not the case in the preceding period, when all groups of jars exhibited a strong

technical homogeneity (THALMANN 2000: 44).

The jars with handles of group 2 (Fig. 5: 3) differ

in shape from their counterparts of Phase P, group 3,

and with the same range of capacities may have

served the same purposes for short-term storage. But

Fig. 5 Jars from Arqa Phase N (MB I)

436

Jean-Paul Thalmann

ments for easy carrying on the head or shoulder; the

handles attached at center of gravity level are especially well suited for pouring when holding the vessel

with both hands.

Only one large vessel with a capacity of 75 litres

coud be reconstructed (Fig. 5: 6), but fragments of

rims of a similar shape are numerous. The wide opening and the two strong handles do not match the

usual types of contemporary storage jars, handleless

and with a restricted neck, easy to seal with a clay

stopper. This could well be also a specialized shape,

new to Phase N, for storing domestic water: the wide

opening allows for drawing up water with pots of all

shapes and sizes, and the vessel can be held by the

handles and tilted down for pouring when it is half or

nearly empty.

Evolution of the repertoire in later periods

Fig. 6 Capacity diagram for Phase N

they are also probably more specifically designed for

transport, because there now exists a number of handleless jars in the same group, which are equally well

suited for short-term domestic storage, but of course

not for transport. A further indication is that we have

from Phase N a number of non-local jar sherds, probably originating from the Byblos area or southern

Lebanon, what can be inferred from their limestone

tempering vs. the strong basaltic component in the

temper of all local wares.

Handleless storage jars are more or less evenly

distributed (which can also be checked from fragments) between groups 2 and 3, and two morphological types only: a plump one with rounded body

(Fig. 5: 1, 2) and a tall slender one (Fig. 5: 4, 5). Probably as for the jars of Phase P, this corresponds to

different products and conditions of conservation,

but the repertoire of Phase N and the capacity

groups show a much higher degree of standardization and specialization.

Jars with handles in group 1 (ca. 15/16 litres,

Fig. 5: 7) are equally interesting, as they probably

are the counterparts of the large jugs of phase P for

carrying water. Jug types in the assemblage of Phase

N are numerous (THALMANN 2000: figs. 44, 46b; 2002:

fig. 8), but they are all of small size and belong to

what may properly be termed tableware. On the

contrary, the jars of group 1, with their moderate

capacity and their shape (rounded body, low handles and tall restricted neck) meet all the require-

For later periods, the number of complete shapes

available from Arqa is too low for significant capacity calculations. But new trends in the production and

use of medium and large size containers are nevertheless apparent.

Very large storage vessels or pithoi (150 litres and

more) appear only with Phase M (MB II) and different types of similar capacity are also produced during Phase L (early LB). Medium-sized jars are

numerous and, much more than during the preceding

phase N, some of them are of non-local origin.

Most of these jars, so far as can be inferred from

fragments, probably fall within a capacity range

between ca. 30 and 40 litres. Is this possibly a more

or less standard capacity for many MB II jars, as

noted above in the case of the Byblos jars? It should

be necessary to accurately measure a wide sample

from many Levantine sites to get the beginning of

an answer. One of the few complete jars from Arqa,

very similar in shape to the Byblos specimens and

ascribed to the very beginning of phase M, holds 33

litres. On the other hand, it is probably not by

chance that very few rims or large body fragments

can be ascribed to the intermediate capacity

group of 60/80 litres, which was well represented,

although in somewhat different ways, in both preceeding phases P and N.

It seems therefore that the specialized production

of different types of storage vessels and the standardization so apparent in the Phase N repertoire

was not continued during phase M. This may be related to the widespread circulation along the Levantine

coast, especially from the beginning of MB II, of the

true commercial jars, well adapted as noted above

to the constraints of maritime trade, but which could

A Seldom Used Parameter in Pottery Studies: the Capacity of Pottery Vessels

also be re-used when empty for all kinds of local storage. At least for the manufacture of medium and

large size containers, a trend in the de-specialization

of local pottery manufacture, vs. the higher specialization of fewer workshops which produced the

commercial jars, probably began at Arqa during

MB II with the wider availability of imported vessels; it becomes more visible in later periods, in all

classes of pottery including tableware.

Canaanite j a r s f r o m T e l l e d - D a b c a

Capacities were calculated for some 20 jars from Tell

ed-Dabca, all Canaanite commercial jars dating to

MB IIA probably originating from southern Palestine (ASTON 2002 : figs. 14 ; SCHIESTL 2002 : fig. 12),

and plotted on the graph Fig. 7. Most surprisingly, it

shows that there is no preferred or standard capacity,

all intermediate values between ca. 14 and 25 litres

being represented. It is obvious that these jars, at

first glance rather standardized because they are all

very similar in shape, size and proportions, did not

however correspond to any standard capacity or system of measures as containers.

Although they have elongated bodies and

restricted, slightly convex bases, most of them still

retain archaic characteristics such as the low

position of the handles placed on the body rather

than on the shoulder. It is possible that a capacity of

ca. 25 litres or a weight of about 30 kilos when full

was, as in the case of group 3 jars from Arqa Phase

P, a practical limit posed by the possibility of easily handling and carrying them or by the mode of

437

stacking in the ships used for transport. Whether it

may be considered as an early stage in the technologies related to maritime trade, in comparison with

the possibility to transport more important quantities of goods in containers of higher capacity (but of

only slightly larger size !), such as the above-mentioned jars from Byblos which are chronologically

hardly earlier than the Jars from Dabca this

should be investigated on the basis of a large database of jar capacities from all sites in the Levant,

and well into MB II and LB.

CONCLUDING

REMARKS

No definite conclusions can be derived from such a

limited sample, but it illustrates the wide range of

problems which may be tackled through systematic

investigation of vessel capacities. The case of the

storage/transport jars at Arqa is perhaps especially

clear because the earlier of the periods considered

(Phases P and N) is there characterized, as everywhere else in the Northern Levant, by a general

trend in handicraft specialization ; and because

there is a strong contrast between Phases P and N,

when no or limited interaction occured between

local productions and imported vessels, and Phase

M or later, when such interactions became more frequent. The proposed model could probably be easily tested on sites where local wares are readily distinguishable from imported ones ; but the excavation of a workshop specialized in the production of

specifically commercial jars is still lacking.

Calculations of capacities made only in a cursory

Fig. 7 Capacities of some MB IIA jars from Tell ed-Dabca

438

Jean-Paul Thalmann

manner on publications of MB II and LB levantine

jars lead to the supposition that different classes of

capacity did exist for different products? different

systems of weights and measures? short or longdistance trade? The test on the jars from Tell edDabca shows that it was not always and everywhere

the same : different chronological stages in the

development of maritime trade may be an explanation, but many others are of course possible.

Before even preliminary results can be obtained, it

is clear that the painstaking compilation of a large

database is necessary, taking into account accurate

measurements only : no too small or approximately

scaled drawings should be used. It is however hoped

that increased interest in capacity calculations and

wider reliance on easy-to-use computer utilities such

as the one proposed above will give significant resuts

in a not too far future.

Bibliography

AMIRAN, R.

ROAF, M.

1969

1989

Ancient Pottery of the Holy Land, Jerusalem.

ASTON, D.A.

2002

Ceramic Imports at Tell ed-Dabca during the Middle

Bronze IIA, 4388, in: BIETAK, M. (ed.) 2002.

Social Organization and Social Activities at Tell Madhhur, 91146, in : HENRICKSON, E.F and THUESEN, I.

(eds.), Upon this Foundation The Ubaid Reconsidered.

Proceedings from the Ubaid Symposium, Elsinore

May 30thJune 1st 1988, Copenhagen.

BIETAK, M. (ed.)

SCHAUB, R.T.

2002

1987

Ceramic Vessels as Evidence for Trade Communication during the Early Bronze Age in Jordan, 247250,

in: HADIDI, A. (ed.), Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan III, London.

1996

Pots as Containers, 231243, in: SEGER, J.D. (ed.),

Retrieving the Past. Essays on Archaeological Research

and Methology in Honor of Gus W. Van Beek. Winona

Lake.

The Middle Bronze Age of the Levant. Proceedings of an

International Conference on MB IIA Ceramic Material,

Vienna, 24th26th of January 2001, CChEM 3, Wien.

ERICSON, J.E. and STICKEL, E.G.

1973

A Proposed Classification System for Ceramics, World

Archaeology 4, 357367.

LE BRUN, A.

1978

La glyptique du niveau 17B de lAcropole. Cahiers de

la Dlgation franaise en Iran 8, 6179.

LE BRUN, A. & Vallat, F.

1978

SCHIESTL, R.

2002

Lorigine de lcriture Suse. Cahiers de la Dlgation

franaise en Iran 8, 1159.

Some Links Between a Late Middle Kingdom Cemetery at Tell ed-Dabca and Syria-Palestine: The

Necropolis of F/I, Strata d/2 and d/1 (= H and G/4),

329352, in: BIETAK, M. (ed.) 2002.

MAEIR, A.

THALMANN, J.P.

1997

2000

Rapport sur les campagnes de 1992 1998 Tell Arqa

(Liban-Nord), BAAL 4, 574.

2002

Pottery of the Early Middle Bronze Age at Tell Arqa

and in the Northern Levant, 363378, in: BIETAK, M.

(ed.) 2002.

2003

Transporter et conserver: jarres de lge du Bronze

Tell Arqa, Archaeology and History in Lebanon 18,

2537.

Tomb 1181: A Multiple-Interment Burial Cave of the

Transitional Middle Bronze Age IIAB, 295340, in:

BEN-TOR, A. et al., Hazor V, An Account of the fifth

Season of Excavation, 1968, Jerusalem.

MAZZONI, S.

1994

Drinking Vessels in Syria: Ebla and the Early Bronze

Age, 245276, in: MILANO, L. (ed.), Drinking in

Ancient Societies. History and Culture of Drinks in the

Ancient Near East, Padova.

RICE, P.

1987

Pottery Analysis: A Sourcebook, Chicago.

TUFNELL, O.

1969

The Pottery of Royal Tombs IIII at Byblos, Berytus

18, 533.

Você também pode gostar

- Turn in Order Rotating BookcaseDocumento7 páginasTurn in Order Rotating BookcasexXAlbert10Xx100% (1)

- Essay Sentence StartersDocumento2 páginasEssay Sentence Startersapi-238421605100% (1)

- Gemstone Quality AnalysisDocumento10 páginasGemstone Quality AnalysisTharanga Sujeeva MadalakandaAinda não há avaliações

- Local Red-Figure Pottery From The Macedonian Kingdom: The Pella Workshop - Nikos AkamatisDocumento58 páginasLocal Red-Figure Pottery From The Macedonian Kingdom: The Pella Workshop - Nikos AkamatisSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- On Beer and Brewing Techniques in Ancient MesopotamiaNo EverandOn Beer and Brewing Techniques in Ancient MesopotamiaNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- TDS Rust Killer 3 in 1Documento3 páginasTDS Rust Killer 3 in 1Izzuddin IbrahimAinda não há avaliações

- Route To Academic SpeakingDocumento150 páginasRoute To Academic SpeakingBull3asaur100% (3)

- Ryan Cayabyab: by Harly Davidson LumasagDocumento10 páginasRyan Cayabyab: by Harly Davidson LumasagHarly DavidsonAinda não há avaliações

- Bulk Materials Handling in The Mining IndustryDocumento12 páginasBulk Materials Handling in The Mining IndustrypabulumzengAinda não há avaliações

- Scientific American Supplement, No. 787, January 31, 1891No EverandScientific American Supplement, No. 787, January 31, 1891Ainda não há avaliações

- Engels Bavay TsingaridaDocumento10 páginasEngels Bavay TsingaridaGermanikAinda não há avaliações

- An Introduction To The Design of MultihuDocumento27 páginasAn Introduction To The Design of MultihuИван ИвановAinda não há avaliações

- Atmospheric TanksDocumento10 páginasAtmospheric Tankssriman1234Ainda não há avaliações

- Golf-Racht, T. D. Van. - Fundamentals of Fractured Reservoir EngineeringDocumento729 páginasGolf-Racht, T. D. Van. - Fundamentals of Fractured Reservoir Engineeringionizedx50% (2)

- Master Wu's Chinese Shamanic Cosmic Orbit QigongDocumento2 páginasMaster Wu's Chinese Shamanic Cosmic Orbit QigongBronson FrederickAinda não há avaliações

- Bosch Continous Vacuum PanDocumento11 páginasBosch Continous Vacuum Pancumpio425428Ainda não há avaliações

- Samuel Beckett-Capital of The RuinsDocumento3 páginasSamuel Beckett-Capital of The RuinsLucinda IresonAinda não há avaliações

- Neoclassical ArchitectureDocumento10 páginasNeoclassical Architecturear.arshadAinda não há avaliações

- TOS 3RDquarter Exam Grade 8Documento6 páginasTOS 3RDquarter Exam Grade 8Shawn IsaacAinda não há avaliações

- Cerámica - ORtonDocumento22 páginasCerámica - ORtonImilla LlnAinda não há avaliações

- A Tentative Reclassification of British Beaker PotteryDocumento20 páginasA Tentative Reclassification of British Beaker PotterybldnAinda não há avaliações

- A Venetian Ship Drawing of 1619 - Richard BarkerDocumento18 páginasA Venetian Ship Drawing of 1619 - Richard BarkerBernabé ThompsonAinda não há avaliações

- Roman Pottery Comparison Reveals Site StatusDocumento10 páginasRoman Pottery Comparison Reveals Site StatusDragan GogicAinda não há avaliações

- Willems - Borgers: Pottery Workshops at Fanum MartisDocumento10 páginasWillems - Borgers: Pottery Workshops at Fanum MartisSonja WillemsAinda não há avaliações

- Performance of Packed Extraction TowerDocumento7 páginasPerformance of Packed Extraction Towercnaren67Ainda não há avaliações

- 2003 DeBoer-Ceramic Assemblage Variability in The Formative of Ecuador and PerúDocumento49 páginas2003 DeBoer-Ceramic Assemblage Variability in The Formative of Ecuador and PerústefanimamaniescobarAinda não há avaliações

- Excavations at Stansted Airport: Charred PlantsDocumento50 páginasExcavations at Stansted Airport: Charred PlantsFramework Archaeology100% (1)

- J. Hawthorne - Vessel Volume As A Factor in Ceramic Quantification-The Case of African RSW (Proceedings From CAA Conference, 1996, 19-24)Documento6 páginasJ. Hawthorne - Vessel Volume As A Factor in Ceramic Quantification-The Case of African RSW (Proceedings From CAA Conference, 1996, 19-24)Dragan GogicAinda não há avaliações

- Arnold, 1990 Some Objections To The Link Between Gallo-Roman Boats and The Roman FootDocumento5 páginasArnold, 1990 Some Objections To The Link Between Gallo-Roman Boats and The Roman FootAnton DivićAinda não há avaliações

- Methods of Kiln ReconstructionDocumento5 páginasMethods of Kiln ReconstructionrverdecchiaAinda não há avaliações

- Bowl SinglesDocumento16 páginasBowl SinglesMonomvs BresAinda não há avaliações

- Early Bronze Age Pottery Industries at Tel Bet YerahDocumento99 páginasEarly Bronze Age Pottery Industries at Tel Bet YerahИванова СветланаAinda não há avaliações

- Mucking Excavation JonesDocumento3 páginasMucking Excavation Jonesjoehague1Ainda não há avaliações

- Performance of Packed Columns - Shulman 1955Documento7 páginasPerformance of Packed Columns - Shulman 1955Ivan RodrigoAinda não há avaliações

- 10 The Material Balance Equation: InitialDocumento46 páginas10 The Material Balance Equation: InitialAyesha AzizAinda não há avaliações

- Scientific American Supplement, No. 446, July 19, 1884No EverandScientific American Supplement, No. 446, July 19, 1884Ainda não há avaliações

- Order.: TuscanDocumento1 páginaOrder.: TuscanreacharunkAinda não há avaliações

- Scientific American Supplement, No. 561, October 2, 1886No EverandScientific American Supplement, No. 561, October 2, 1886Ainda não há avaliações

- 1vature: (AI lUL 20Documento1 página1vature: (AI lUL 20Anantha KishanAinda não há avaliações

- March 17, 1887) Na7Ure: © 1887 Nature Publishing GroupDocumento1 páginaMarch 17, 1887) Na7Ure: © 1887 Nature Publishing GroupEugenio AldoAinda não há avaliações

- Mythe To Mitcheldean Mains Reinforcement, Gloucestershire - PotteryDocumento24 páginasMythe To Mitcheldean Mains Reinforcement, Gloucestershire - PotteryWessex ArchaeologyAinda não há avaliações

- Pottery Production in Ancient Akrotiri IELTS Reading Answers With ExplanationDocumento8 páginasPottery Production in Ancient Akrotiri IELTS Reading Answers With Explanationace teachingmaterialsAinda não há avaliações

- Archaeological fieldwalking in Essex 1986-2005Documento13 páginasArchaeological fieldwalking in Essex 1986-2005roobarbAinda não há avaliações

- Statistical Observations On The Phoenician Pottery of KitionDocumento51 páginasStatistical Observations On The Phoenician Pottery of KitionEl fenicio pilla librosAinda não há avaliações

- Corinthian Kotyle WorkshopsDocumento20 páginasCorinthian Kotyle WorkshopsIgnasi Vidiella PuñetAinda não há avaliações

- 3-Pass Trays Friend or FoeDocumento10 páginas3-Pass Trays Friend or FoeIan MannAinda não há avaliações

- Distillation Sieve Trays Without Downcomers Prediction ofDocumento9 páginasDistillation Sieve Trays Without Downcomers Prediction ofSanjeev Kumar100% (1)

- Aic 690300311 PDFDocumento9 páginasAic 690300311 PDFJabulani Jays MadonselaAinda não há avaliações

- Chromatography: A Brief IntroductionDocumento5 páginasChromatography: A Brief IntroductionLiyana HalimAinda não há avaliações

- Intercolumni: AtionsDocumento1 páginaIntercolumni: AtionsreacharunkAinda não há avaliações

- Worked Bone From The BACH AreaDocumento16 páginasWorked Bone From The BACH AreaMariam EloshviliAinda não há avaliações

- 1964 - Van Hengel - Suggestions For The SettingsDocumento4 páginas1964 - Van Hengel - Suggestions For The SettingsCecilio Valderrama100% (1)

- Kuchuk, F. J. - Well Testing and Interpretation For Horizontal WellsDocumento6 páginasKuchuk, F. J. - Well Testing and Interpretation For Horizontal WellsJulio MontecinosAinda não há avaliações

- Marine Clastic Reservoir Examples and Analogues (Cant 1993) PDFDocumento321 páginasMarine Clastic Reservoir Examples and Analogues (Cant 1993) PDFAlberto MysterioAinda não há avaliações

- Uncovering Ancient Texts with 3D ImagingDocumento14 páginasUncovering Ancient Texts with 3D ImagingterawAinda não há avaliações

- Spe7480 Welltest by NG Intwo-Phase Geothermal Wells: Alain C. (%ingarten, Member Spe-Aime, B.R.G.MDocumento12 páginasSpe7480 Welltest by NG Intwo-Phase Geothermal Wells: Alain C. (%ingarten, Member Spe-Aime, B.R.G.MRamaDhanaMuhammadEfendiAinda não há avaliações

- Note 4 - Distillation Efficiencies For Tray and Packed Towers and FloodingDocumento26 páginasNote 4 - Distillation Efficiencies For Tray and Packed Towers and FloodingKaleesh100% (1)

- Early Iron Age Balance Weights at Lefkandi, PDFDocumento12 páginasEarly Iron Age Balance Weights at Lefkandi, PDFDanisBaykanAinda não há avaliações

- Scientific American Supplement, No. 832, December 12, 1891No EverandScientific American Supplement, No. 832, December 12, 1891Ainda não há avaliações

- Management of Scale Up of Adsorption in Fixed-Bed Column Systems - Odysseas KopsidasDocumento45 páginasManagement of Scale Up of Adsorption in Fixed-Bed Column Systems - Odysseas KopsidasΟδυσσεας ΚοψιδαςAinda não há avaliações

- Pottery From The Diyala RegionDocumento494 páginasPottery From The Diyala RegionAngelo_ColonnaAinda não há avaliações

- Manuscript 1Documento45 páginasManuscript 1Anonymous kqqWjuCG9Ainda não há avaliações

- Multipass Trays - Ref12Documento31 páginasMultipass Trays - Ref12SarahAinda não há avaliações

- Structural inversion perspectives from petroleum industryDocumento29 páginasStructural inversion perspectives from petroleum industryPutri AlikaAinda não há avaliações

- Pottery as a Source of InformationDocumento22 páginasPottery as a Source of InformationAdi DžemidžićAinda não há avaliações

- Composition and Production of Late Antique Glass Bowls Type HelleDocumento10 páginasComposition and Production of Late Antique Glass Bowls Type HelleGarlic LahsunAinda não há avaliações

- The Hyperbolic-Paraboloidal Shell and Its Mechanical PropertiesDocumento9 páginasThe Hyperbolic-Paraboloidal Shell and Its Mechanical PropertiesmateovarelaortizAinda não há avaliações

- Shallow Raceway Design for Sustainable Sole AquacultureDocumento26 páginasShallow Raceway Design for Sustainable Sole AquaculturePeter YoungAinda não há avaliações

- Papadolpulos and Cooper 1967Documento4 páginasPapadolpulos and Cooper 1967allukazoldikAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Danish Textiles From Bogs and Burials A Comparative Study of Costume and Iron Age TextilesDocumento396 páginasAncient Danish Textiles From Bogs and Burials A Comparative Study of Costume and Iron Age Textileso_djuraAinda não há avaliações

- Global Mapper Shortcut Key ListDocumento2 páginasGlobal Mapper Shortcut Key ListhenataaAinda não há avaliações

- 2001maize, Matrilocality, Migration, and Northern Iroquoian Evolution.Documento34 páginas2001maize, Matrilocality, Migration, and Northern Iroquoian Evolution.o_djuraAinda não há avaliações

- 1999faunal Materials and Interpretive Archaeology-Epistemology Reconsidered PDFDocumento30 páginas1999faunal Materials and Interpretive Archaeology-Epistemology Reconsidered PDFo_djuraAinda não há avaliações

- Olympus SZ-61TR ManualDocumento28 páginasOlympus SZ-61TR ManualRonnie OcampoAinda não há avaliações

- Zene U Africi - Obrada ZemljeDocumento150 páginasZene U Africi - Obrada Zemljeo_djuraAinda não há avaliações

- TaraDocumento12 páginasTarao_djuraAinda não há avaliações

- TaraDocumento12 páginasTarao_djuraAinda não há avaliações

- Ceramica - Sober Et Al.Documento8 páginasCeramica - Sober Et Al.Edwin Angel Silva de la RocaAinda não há avaliações

- Karasik Instructions For Users of The Module Capacity PDFDocumento10 páginasKarasik Instructions For Users of The Module Capacity PDFronaldloliAinda não há avaliações

- Of Calories and CultureDocumento4 páginasOf Calories and Cultureo_djuraAinda não há avaliações

- Sensi: Operating InstructionsDocumento2 páginasSensi: Operating Instructionso_djuraAinda não há avaliações

- Pendidikan Seni Tari Melalui Pendekatan Ekspresi Bebas, Disiplin Ilmu, Dan Multikultural Sebagai Upaya Peningkatan Kreativitas SiswaDocumento15 páginasPendidikan Seni Tari Melalui Pendekatan Ekspresi Bebas, Disiplin Ilmu, Dan Multikultural Sebagai Upaya Peningkatan Kreativitas SiswaMob AsrlAinda não há avaliações

- Digital Designs Catalog: True Type FontsDocumento20 páginasDigital Designs Catalog: True Type FontsDavid Eduardo Guerra Guerra100% (1)

- Textual Integrity in OthelloDocumento16 páginasTextual Integrity in Othellopunk_outAinda não há avaliações

- Gedung Sate Teks DeskriptifDocumento2 páginasGedung Sate Teks DeskriptifHumaira Adiba100% (1)

- Resale: Honey, I'm HomeDocumento1 páginaResale: Honey, I'm HomeSarahMagedAinda não há avaliações

- Router Table - RTA300: Supercedes Earlier Model RTA300 - July 2002Documento2 páginasRouter Table - RTA300: Supercedes Earlier Model RTA300 - July 2002j_abendstern4688Ainda não há avaliações

- Learning Activity Sheet: ExploreDocumento3 páginasLearning Activity Sheet: ExploreGhail YhanAinda não há avaliações

- (Unfinished) The Analysis of Sound Devices of Poems in The Novel Entitled "Dead Poets Society"Documento16 páginas(Unfinished) The Analysis of Sound Devices of Poems in The Novel Entitled "Dead Poets Society"Fitrie GoesmayantiAinda não há avaliações

- ColourDocumento2 páginasColourapi-305963468Ainda não há avaliações

- Study On Rapier Weaving Mechanism.Documento11 páginasStudy On Rapier Weaving Mechanism.Naimul HasanAinda não há avaliações

- Edward Bond, A Distinctive Voice in Modern British DramaDocumento4 páginasEdward Bond, A Distinctive Voice in Modern British Dramajazib1200Ainda não há avaliações

- Biografia Billy MclaughlinDocumento2 páginasBiografia Billy MclaughlinBruno Tettamanti100% (1)

- bt gián tiếpDocumento6 páginasbt gián tiếpDuyên LêAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Binders in AhmedabadDocumento4 páginasThesis Binders in Ahmedabadannapagejackson100% (1)

- Visual Arts FAT Grade 5Documento10 páginasVisual Arts FAT Grade 5Jerome FankomoAinda não há avaliações

- ArnisDocumento2 páginasArnisKaye JagutinAinda não há avaliações

- A History of Tell El-Yahudiyeh Typology PDFDocumento30 páginasA History of Tell El-Yahudiyeh Typology PDFSongAinda não há avaliações

- 2012 Fall/Winter CatalogDocumento32 páginas2012 Fall/Winter CatalogEverything HappyAinda não há avaliações

- Pretest in English 9 Section provides concise drama termsDocumento1 páginaPretest in English 9 Section provides concise drama termsLoujean Gudes MarAinda não há avaliações

- Catchingsnowflakes ArtDocumento3 páginasCatchingsnowflakes Artapi-438357152Ainda não há avaliações

- B.A. Hons. Karnataka MusicDocumento30 páginasB.A. Hons. Karnataka MusicrajivkarunAinda não há avaliações

- Teachers Day Anchor - ScriptDocumento2 páginasTeachers Day Anchor - ScriptAngielica Pirante100% (5)