Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

225 Kramer-Entangled With Affects. Finding Objects of Inquiry Within The Ethnographic Research Process

Enviado por

kitarsemulaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

225 Kramer-Entangled With Affects. Finding Objects of Inquiry Within The Ethnographic Research Process

Enviado por

kitarsemulaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Issue 5.

1 / 2016: 4

Entangled with

affects. Finding

objects of inquiry

within the

ethnographic

research process

Hannes Krmer

This paper is concerned with the ways scientists are

engaged in finding research objects. More

particularly, it deals with the role of emotions and

affects during the research process. There is a long

and thorough discussion within the social sciences

methodology about the ways objects of inquiry

should be identified. Quite a few authors have

described idealized ways of approaching objects,

actors, situations and gathering data about those

phenomena. There are a lot of texts about the ways

epistemic objects are constructed and brought into

existence by writing about them. What is striking

about those tales of the field (van Maanen) are at

least two aspects: The first is the one-sided focus

on success. Research accounts are usually

conceptualised as modern tales of a heroic

researcher who can solve every research problem if

not easily than at least successfully.[1] If the

resistances and the failures of the research process

become part of the presentations at all, they only

appear as challenges that were managed well,

neglecting their rather complex intertwining in the

whole process. As the Australian sociologists

Malpas and Wickham put it: Sociology, like all

modern social sciences, concentrates most of its

energy on success.[2] Related to the first problem,

the second shortcoming of those tales of the field

concerns the apparent affective neutrality of the

research process.[3] Although there are some

intriguing books on the practices of fieldwork as

well as studies concerned with the emotions of the

actors involved, there is only little discussion about

the entanglements of affect and research

practice.[4] The research process seems to follow

the credo of an analytical and neutral endeavour. It

is this second aspect I want to focus on in the

following by identifying three typical research

situations and ask for their very research object and

the role emotions and affects play in such

situations. I will argue that the identification of a

research object is crucially linked to the

researchers emotions and to the affects in the

specific process of doing research.

Considering the subjective position of the

ethnographer, emotions and situational affects are

always part of the research process, and if it is only

to elude them. While I am building on rich and

ongoing discussions within the emotions and

affectivity research community,[5] I will omit an indepth discussion of differences between the

concepts of emotions, feelings or affects in favour

of a detailed look at situational assemblages of

moods, objects, rhythms and subjects in three

different cases from the field. However, a few

words are necessary to provide a rough sketch of

continentcontinent.cc / ISSN: 21599920|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Issue 5.1 / 2016: 5

my use of those heavily discussed terms. I will

speak of emotions to conceptualise a rather fixed

shape of sentiments. Emotions are more or less

embedded in a cultural and verbal environment.

They are a solidified and addressable quality.

Instead, by focusing on affects the undecidable

character of sentiments is addressed, including a

more vague but still sensible notion of feeling.

Following Deleuze/Guattaris often cited

understanding of affects as something pre-cultural

the quality of such oscillations seems to be less

defined: Affects are entangled with percepts,

sensations that cannot be properly described.[6] At

the same time, both terms, emotion and affect,

represent attempts to overcome the subjective bias

and integrate a material and bodily performance

practice by indicating the affect as well as the

emotion as something between an object and an

interpreting subject.[7] This helps us consider

subjects and objects both as

co-constitutive participants of a situationally

specific, causal relationship, in which we cannot

know beforehand whether it is the actors or the

objects that are responsible for the sensed and

perceived qualities. In short, I am going to use the

term emotions to refer to known sociocultural

expressions of feelings, while with affects I describe

less-defined situational moods. Both dimensions

can build upon another if we conceptualize

emotions as a specific interpretation of an affective

state or the blurriness of an emotion as the sign for

the presence of affects. The conceptual differences

will become clearer in the following examples.

Stepping into the realm of creative mystery

The first situation I want to examine highlights a

common starting problem in ethnographic field

work: How to get access to the field? In my

research I was interested in the practices people

perform to produce something they refer to (and

sell) as creative. I wanted to understand the

secret mystery of the creative industries. To put it

in a research question: How do the actors meet the

daily demand for creative products? By following

the actors, actions and objects within creative

workplaces I wanted to shed light on the social

accomplishment of creativity, that means on

production practices and the objects entangled

with these performative processes. To get a firm

grip on the practical dimension of creative labour I

conducted an ethnographic case study in the

continentcontinent.cc/index.php/continent/article/view/225

Hannes Krmer

advertising industry, focusing on daily working

activities. For over six months in 2008 and 2009 I

was employed as a copywriting trainee in two

advertising agencies. The reason why I became a

copywriting trainee was tightly linked to the

impermeability of the field. Immune reactions

(Stephan Wolff) from within the field resulted in

refused applications for research positions. I tried

instead to cast a net by conducting interviews with

different advertising professionals. In these

interviews I realised that my approach to ask for a

guest-research-position had been the wrong

strategy. The place for novices in the field seemed

to be a traineeship in an agencys art department.

Since I considered myself not gifted enough with

graphic design skills I applied for a copywriting

position. To be accepted for a traineeship the

applicant has to pass a test the so called copy

test.

The copy test as an entry point transforms field

access into an assignment with clear rules. This

turns the copy test itself, usually a multi-page

document where the applicant is asked to produce

copies, claims, spots, scribblings etc., into an

interesting kind of document for the researcher.

Today it may lose more and more its importance,

but some years ago it could be considered the gate

that youngsters of the field had to stride through.

To apply with a copy test takes some reasonable

amount of time they say it takes about ten days

and even if you hand in your copy test an internship

is not guaranteed. Apparently, it represents a

demanding object and requires certain skills I

myself didnt have or at least I didnt know whether

I had them. It forces you to give ideas a form (even

if you dont have any ideas) and it

thereby objectifies the process of generating

ideas as much as the process of application. It

connects you with the people you want to convince

that you are an interesting trainee and at the same

time it makes them present in a mediated way. It

prepares and reorganizes a certain affective

potential of an interview situation in which

sympathy levels and gestures are negotiated as

much as thoughts - for the copy test itself is an

affective medium.

All in all, the interaction with such a document may

create a certain anxiety in regards to the odds for

field access. Am I good enough? What happens if I

fail? This might be my last chance, the decisive

moment of my whole research endeavour?

Issue 5.1 / 2016: 6

Apparently, these affective attachments point to an

uncertain and unseizable future. Like other

phenomena of in-betweenness (and their subjective

instantiations like trust) the affectivity of an

application process does not fully translate into

discursive certainty and knowledge. It derives its

power from the unspoken and pre-propositional.

The copy test is a powerful and hopeful thing at the

same time. Such a quality highlights the test as a

recognizable object, as a thing one has to deal with

if one wishes to enter the field. It is this very

resistance, this special affectivity I sensed, which

suddenly transferred an object of anxiety into an

object of inquiry.

I am arguing that my increased interest in the copy

test as an object of inquiry is tightly linked to the

affective state I encountered and struggled with

before I could even think of conceptually naming

and integrating these sentiments into theoretical

frameworks. The interaction with the copy test

evoked such a strong affective involvement that it

generated attention which finally was canalised

as academix attention. Following the basic

ethnographic question What the hell is going on

(Clifford Geertz in an interview with Gary A.

Olsen)[8] the researcher has to rely on her own

sensorial engagement with the object which

includes feelings of attachment that might be

blurry at the moment of encounter. That does not

render a systematic and less emotionally involved

mode of inquiry unnecessary; however,

acknowledging the affective dimension might help

in finding interesting and important research

objects. So I, for instance, started asking questions:

How can an object unfurl so much power? What

does such an object do to my attention as a

researcher? May I learn something about the field

by examining its entry points?

Turning to those questions also minimized the

brute force of the object and helped me to balance

my own emotional budget in that it incited a desire

to shift modes - from seeking employment back to

research - and to reconsider the role of the object from a challenge into a research object. But the

reverse effect is everything but

inconceivable: Resistant and affect-evoking objects

might also produce repulsion. They can annoy the

researcher in a way that she is relieved when

leaving it behind. Either way, affective encounters

in the research process do guide attention and

regulate engagement.

continentcontinent.cc/index.php/continent/article/view/225

Hannes Krmer

Sensing it right

Lets take a little leap within the research trajectory

and move forward to my traineeship in an

advertising agency. I eventually succeeded in

getting access through a combination of my copy

test application and a net of helpful contacts. Once

I started my work in the agency my specific double

role as a researcher and an intern was forgotten

quite quickly, leaving me with my new role as

copywriting trainee. I was part of all everyday

working situations that other employees had to

face: writing copies, attending brainstormings,

negotiating deadlines with the account guys,

brewing up, walking the dog and so on. Given I

found the time, I was collecting

data about and in certain situations; especially

situations that I believed to represent the mundane

agenda of agency life.

Collecting data was not always easy. Lets take

brainstorming situations for example. I tried to take

some pictures of the room and materials after the

sessions had ended, and I wrote my field protocols

in the evening. In some occasions I was able to

record an audio file of such brainstorming sessions.

What I figured out after a while was that in these

brainstorming situations something happened that

I couldnt quite get to terms with using the usual

sociological or social-anthropological vocabulary.

There was something opaque about the situation,

an emergence that escaped the usual categories of

individuals, interactions, groups, hierarchies, power

etc. At the end of such brainstormings there was a

list with different ideas, but why specifically those

ideas made it on the list I could not quite

understand.

Why are some ideas considered worth following

while others are discarded? How do the

protagonists identify good ideas? Without more

information about the context I wasnt able to

answer those questions. When I asked colleagues

about their strategies they usually answered with a

variation of the phrase oh, yes that is my

experience. In order to make sense of such

slippery vocabulary as experience I re-evaluated

my audio files and fieldnotes to find something I

would call the sense of a right idea.[9] While my

interlocutors often pretended to know that an idea

is the right one, I suspect that sensing is a more

adequate concept to describe the process. By

Issue 5.1 / 2016: 7

trying to remember the last idea sessions and

being very attentive in the next ones, I figured out

that sensing a right idea was not necessarily a

reflexive, propositional or positive knowledge. It

seemed to be an affective attachment towards

some ideas and an affective neutrality towards

others. After a while I noticed that even I was

weighing ideas by a hidden script rather than well

and long thought reasons. My sensing the right

idea skills were not always congruent with the

others but they met quite frequently.

I became attentive to this dimension and started

looking for those moments in which a good idea

would emerge. I started listening to my field

recordings again and found different characteristics

of situations where ideas were marked as good. On

the level of everyday talk I could observe an

increase in alternating and overlapping speech

acts, a higher frequency of turn-takings and a

general verbal reaction towards an emerging idea

by every participant. In addition, I found that the

people were gesturing a lot in such situations and

they used to create drawings. I labelled it an

atmosphere of active tension which emerges as a

result of interactions between different people,

activities and materials. I use the term atmosphere

to illustrate that sensing must be understood as a

collective effort and achievement. In contrast to a

great deal of contemporary literature on

creativity[10] I argue that in those situations several

people and several objects are involved in

producing an affective state of idea-sensing. But

before entering this analytical mode of theorizing

and reflecting on complexity theory and

epistemology, I first and foremost had learned

something as a participant of the field. Linking this

to the overall topic of this short paper you could

say it was my own involvement as sensory being

within the affective assemblage of the situation

which enabled me to attend, attune myself to and

eventually interpret this practice of knowledge

production as such. For me the sensing of an idea

transformed into the sensing of a research object.

To put it bluntly: Affective and emotional attention

can be considered an epistemological technique

for identifying and analysing research problems in

ethnographic research.

De-Affection and Re-Affection

Finally I fast forward again on the timeline of my

continentcontinent.cc/index.php/continent/article/view/225

Hannes Krmer

research trajectory to being back at my desk at the

university. I would like to shed some light on the

context of discovery in the work with field

protocols. Scientific texts are usually considered as

emotionless genre of writing. Starting with the

early fieldnotes, followed by the later field

protocols, then analytical notes, succeeded by draft

versions of a manuscript and finally a published

article, the academic is encouraged to remove all

traces of personal feelings towards the research

object. In its extremes it sometimes seems as if the

author had been erased.

Such an undoing of agency has been criticised by

a number of authors, most prominently in the social

anthropological writing culture

debate.[11] Despite all the methodological

achievements this discussion brought it still seems

as if the ideal of scientific text genres is still

emotional neutrality. This should not come as a

surprise if one considers the special textual

category which is used to manufacture knowledge

about different cultures.

Let us take the example of field protocols. At first

sight they follow a simple logic of representation

since they are supposed to represent the situation

as observed by the researcher. The author and her

emotions are supposed to vanish between the lines

of a more or less neutral description (i.e. without

subjective tendencies). But at the same time field

protocols can not entirely fulfil this scientific desire

for neutrality since they are subjective documents

reflecting the position of the researcher and

functioning as highly selective memory trace. Field

protocols are supposed to remind the researcher of

certain situations, while being organized as

allegedly neutral descriptions.[12] In the literature

you can find a mixture of those two performances

to remember and to represent. It is especially the

second one which is usually mentioned to cement

the neutrality of research descriptions.[13] However,

by neglecting the non-neutrality and affective

disposition of fieldnotes and protocols we are

destined to miss out on an extremely valuable

resource for doing ethnographic research.

If we look a little closer at the practices of writing

within research situations we can differentiate

traces of affectivity (i.e. of emotive excess, of that

feeling which has not yet been given its proper

name) in different text genres. Take the early

fieldnotes and the later field protocols. While

Issue 5.1 / 2016: 8

fieldnotes are often barely systematized and

marked by volatility and incompleteness, field

protocols follow a linear mode of explanation, a

more extensive capturing of a situation. The first

one is written while literally being in the field in

my case while being a copywriter. You write down

small pieces of information, parts of sentences,

some words you consider meaningful in the

situation. Later on, being back at your desk at

home you prepare the more elaborated field

protocols. After my business day I took some time

and added aspects I still had on my mind,

completed sentences and offered first analytical

connections. By doing so I produced a much more

consistent form of text and at the same time

reduced evidence of my affective and emotional

involvement.

The fieldnotes still carry some traces of emotions

and affective potentials; you can guess ones anger

by the depth of the pencil imprint, you see ones

frustration by the selection of words and

exclamation marks (and again! I was asked to

do), you can find traces of joy in emoticon-like

drawings and corresponding expressions. Behind

and between the defined descriptors you sense the

original affective involvement without having

pinpointed a word for it yet. In the next step of the

field protocol such emotive traces are gone. Of

course one can still read, I disliked being asked

several times to but this is only an account of

those emotions that have already become the topic

of the research rather than its resource. So the

processes of data interpretation and text

(re)production seem to increasingly neutralise the

affective potentials and emotive links to fieldnotes

and to the represented situation itself.

At the same time, new affective and emotive

qualities emerge. First, the field protocol itself

functions as an aesthetic object that follows

rhetorical rules of persuasion. It tries to convince

the researcher that it transports interesting

aspects.[14] The emotive quality emerges as a

promise of dense and material-rich

description: That there is more to it. Second, field

protocols capture and direct attention. If it is the

tenth time you read about the same object you

become either curious about this artefact or bored.

This can be understood as an affective emergence.

An artefact that did not seem of particular interest

while being in the field might emerge as a key

object due to the interactions of researcher and

continentcontinent.cc/index.php/continent/article/view/225

Hannes Krmer

documentation. Third, and strongly connected with

the last point, I would argue that it is again a

sensing of a research object which guides the

researcher. The researcher tries to tease something

out of the description. At the same time it is not

only about letting the research object speak, giving

it a platform to emerge, but it is also about the

ways an object can be listened to. The researcher

has to test her interpretations. Therefore she is

connecting herself and she gets connected to the

field protocol, hooked by an emotive state of

interestedness, which guides her towards further

research objects. Such operations of

sensing interesting data, I would say, can not be

conceptualised sufficiently as propositional

knowledge. Rather the interpretation points to a

kind of emotive reflexivity and affective attunement

as an important part of the research process.

However, the identification of the research object

from the protocols is tested by the researcher

herself as well as in colloquia or small research

groups and thereby gets more and more stabilised

and consciously worked on.

Conclusion

This small contribution argued that affects and

emotions intervene in the process of finding

research objects. All the way from the moment we

try to get access to the field to the process of

homing in on artefacts at the researchers desk, the

de-subjective neutrality of the scientist is

supplemented or even substituted by a strong

emotional and affective involvement. Sometimes

one wades in the knee-deep mud of the empirical

world, sometimes one feels anxiety and anger,

sometimes fun and confidence prevail, sometimes

it is necessary to allow oneself to be a feeling and

sensing being in order to permeate situations of

interest. I concentrated on three different

entanglements of scientific interest, affect and

emotions in the process of identifying research

objects, although there are certainly more. They

directed my attention towards objects like the copy

test, they helped to actively comprehend practices

like generating and identifying good ideas and

they guided the process of retrieving different

elements for interpretations of my observations

from the field. Accordingly, emotions and affects

should not only be treated as research topics but as

analytical resources and techniques of attunement.

Issue 5.1 / 2016: 9

To feel differently and to sense affective resistance

or exhilaration can function as an effective indicator

for the researcher to understand and describe her

field of interest.

Hannes Krmer

History)? A Bourdieuan Approach to Understanding

Emotion. History and Theory 51, no. 2 (2012):

193-220; Robert Seyfert Beyond Personal Feelings

and Collective Emotions: Toward a Theory of Social

Affect. Theory, Culture & Society 29, no. 6 (2012):

27-46.

REFERENCES

[1] This account is no exception. Failing in writing

about failure can actually only be read in its nonexistence. This happened to me once, when an

article proposal on the topic of failure and

resistance was rejected in the peer-reviewing

process. Looking back, I should have published at

least the rejection.

[2] Jeff Malpas and Gary Wickham Governance

and Failure: On the Limits of Sociology. Australian

and New Zealand Journal of Sociology 31, no. 3

(1995): 37.

[3] An important exception can be found in Nigel

Barleys The Innocent Anthropologist: Notes From

a Mud Hut. New York: Viking Penguin, 1983.

[4] See for instance: Thomas Stodulka Spheres of

Passion: Fieldwork, Ethnography and the

Researcher's Emotions. Curare. Journal for

Medical Anthropology 38, no. 1+2 (2015):

100-116.

[5] Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth

(eds.). The Affect Theory Reader. Durham, London:

Duke University Press, 2010.; Ute Frevert et

al. Emotional Lexicons: Continuity and Change in

the Vocabulary of Feeling 1700-2000. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2014; Andreas

Reckwitz Praktiken und ihre Affekte Mittelweg

36. Zeitschrift des Hamburger Instituts fr

Sozialforschung 24, no. 1+2 (2015): 27-45.

[6] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari What is

Philosophy? London: Verso, 1994: Ch. 7

[7] Monique Scheer Are Emotions a Kind of

Practice (and Is That What Makes Them Have a

continentcontinent.cc/index.php/continent/article/view/225

[8] Gary A. Olsen The Social Scientist as Author:

Clifford Geertz on Ethnography and Social

Construction Journal of Advanced

Composition 11, no. 2 (1991): 245-268.

[9] At first sight it doesnt help to replace one

slippery term by another one, but after giving it a

second thought it did, because sensing rather

points to a process of the present, while the notion

of experience more often refers to the past as a

growing pile of sedimented layers.

[10] Robert J. Sternberg The Nature of

Creativity. Creativity Research Journal 18, no. 1

(2006): 87-98; Charlotte Bloch Flow: Beyond

Fluidity and Rigdity. A Phenomenological

Investigation. Human Studies 23, no. 1 (2000):

43-61; Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi Creativity. Flow and

the Psychology of Discovery. New York: Harper

Collins, 1996.

[11] James Clifford and George E. Marcus

(eds.) Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of

Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1986.

[12] Writing emotional diaries parallel to the normal

field notes and protocols could be a way to reflect

the meaning of emotions and affects within the

research process; see Stodulka 2015 op.cit.

[13] Like I mentioned there is some strong critique

of such a positivistic usage of representation in the

Writing Culture Debate (cf. Paul Rabinow

Representations Are Social Facts: Modernity and

Post-Modernity in Anthropology In Writing

Culture. The Poetics and Politics of

Ethnography. edited by James Clifford and George

E. Marcus, 234-261. Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1986), but usually it is not

Issue 5.1 / 2016: 10

expanded to the practice of the fieldwork itself; cf.

for an exception an article by Stefan Hirschauer:

Putting Things Into Words. Ethnographic

Description and the Silence of the Social. Human

Studies 29, no. 4 (2006), 413-441.

[14] An interesting account of the social practice of

discovering research objects within the natural

sciences can be found in Karin Knorr-Cetina

Sociality with Objects. Social Relations in

Postsocial Knowledge Societies. Theory, Culture &

Society 14, no. 4 (1997): 1-30.

continentcontinent.cc/index.php/continent/article/view/225

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Hannes Krmer

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Explaining The Placebo Effect: Aliefs, Beliefs, and ConditioningDocumento33 páginasExplaining The Placebo Effect: Aliefs, Beliefs, and ConditioningDjayuzman No MagoAinda não há avaliações

- Wood - Neal.2009. The Habitual Consumer PDFDocumento14 páginasWood - Neal.2009. The Habitual Consumer PDFmaja0205Ainda não há avaliações

- EnglishDocumento128 páginasEnglishImnasashiAinda não há avaliações

- Thinking in English A Content Based ApprDocumento10 páginasThinking in English A Content Based ApprDolores Tapia VillaAinda não há avaliações

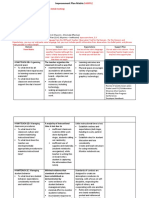

- Improvement Plan MatrixDocumento3 páginasImprovement Plan MatrixJESSA MAE ORPILLAAinda não há avaliações

- Reopening of Cubberley High SchoolDocumento5 páginasReopening of Cubberley High Schoolapi-26139627Ainda não há avaliações

- Module 13 Ethics Truth and Reason Jonathan PascualDocumento5 páginasModule 13 Ethics Truth and Reason Jonathan PascualKent brian JalalonAinda não há avaliações

- ACL Arabic Diacritics Speech and Text FinalDocumento9 páginasACL Arabic Diacritics Speech and Text FinalAsaaki UsAinda não há avaliações

- Cambridge Secondary 1 Checkpoint: Cambridge Assessment International EducationDocumento12 páginasCambridge Secondary 1 Checkpoint: Cambridge Assessment International EducationOmar shady100% (1)

- Running Head: Nursing Philospohy and Professional Goals Statement 1Documento8 páginasRunning Head: Nursing Philospohy and Professional Goals Statement 1api-520930030Ainda não há avaliações

- Sociolinguistic Research Proposal 202032001Documento15 páginasSociolinguistic Research Proposal 202032001FitriaDesmayantiAinda não há avaliações

- Pangarap Pag Asa at Pagkakaisa Sa Gitna NG PandemyaDocumento2 páginasPangarap Pag Asa at Pagkakaisa Sa Gitna NG Pandemyamarlon raguntonAinda não há avaliações

- English 2 Rhyming Words PDFDocumento40 páginasEnglish 2 Rhyming Words PDFJovito Limot100% (2)

- Dll Catch Up Friday- Lilyn -Apr 26 - CopyDocumento2 páginasDll Catch Up Friday- Lilyn -Apr 26 - Copyjullienne100% (1)

- Word Retrieval and RAN Intervention StrategiesDocumento2 páginasWord Retrieval and RAN Intervention StrategiesPaloma Mc100% (1)

- Applied Linguistics Lecture 1Documento18 páginasApplied Linguistics Lecture 1Dina BensretiAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan Bahasa Inggris SMK Kelas 3Documento5 páginasLesson Plan Bahasa Inggris SMK Kelas 3fluthfi100% (1)

- Project 3 Case Study Analysis Final SubmissionDocumento4 páginasProject 3 Case Study Analysis Final Submissionapi-597915100Ainda não há avaliações

- The Discovery of The UnconsciousDocumento325 páginasThe Discovery of The UnconsciousChardinLopezAinda não há avaliações

- Concept Attainment Lesson PlanDocumento4 páginasConcept Attainment Lesson Planapi-189534742100% (1)

- Wikipedia'Nin Turkce GrameriDocumento25 páginasWikipedia'Nin Turkce GrameriΚυπριανός ΚυπριανούAinda não há avaliações

- Reaction On The Documentary "The Great Hack"Documento1 páginaReaction On The Documentary "The Great Hack"jyna77Ainda não há avaliações

- English Grammar and Correct Usage Sample TestsDocumento2 páginasEnglish Grammar and Correct Usage Sample TestsOnin LaucsapAinda não há avaliações

- Anthropological Perspective of The SelfDocumento15 páginasAnthropological Perspective of The SelfKian Kodi Valdez MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- SAP PM Codigos TDocumento7 páginasSAP PM Codigos Teedee3Ainda não há avaliações

- More 3nget - Smart - Our - Amazing - Brain - B1Documento31 páginasMore 3nget - Smart - Our - Amazing - Brain - B1entela kishtaAinda não há avaliações

- Grammar Guide to Nouns, Pronouns, Verbs and MoreDocumento16 páginasGrammar Guide to Nouns, Pronouns, Verbs and MoreAmelie SummerAinda não há avaliações

- Project Management British English StudentDocumento3 páginasProject Management British English StudentOviedo RocíoAinda não há avaliações

- Artificial Intelligence Machine Learning 101 t109 - r4Documento6 páginasArtificial Intelligence Machine Learning 101 t109 - r4Faisal MohammedAinda não há avaliações

- ThesisDocumento39 páginasThesisJeanine CristobalAinda não há avaliações