Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A Selective-Pressure Impression

Enviado por

jorgeTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Selective-Pressure Impression

Enviado por

jorgeDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A selective-pressure impression technique for the edentulous maxilla

Jacqueline P. Duncan, DMD, MDSc,a Sangeetha Raghavendra, DMD, MDSc,b and

Thomas D. Taylor, DDS, MSDc

University of Connecticut School of Dental Medicine, Farmington, Conn

This article describes a selective-pressure impression technique for the edentulous maxilla that is intended

to compensate for the polymerization shrinkage of heat-polymerized polymethyl methacrylate resin and

provides improved palatal adaptation of the definitive denture base. (J Prosthet Dent 2004;92:299-301.)

here are several definitive impression techniques

for recording the edentulous maxilla. These techniques

may be categorized as functional, nonpressure, and

selective-pressure impressions. Unfortunately, the dentures made with these techniques rarely create the

pattern of tissue contact desired, owing to denture base

distortion caused by polymerization shrinkage that occurs with heat-polymerized polymethyl methacrylate

(PMMA).1,2

With the functional or closed-mouth technique,

the patient exerts masticatory force at the desired vertical

dimension of occlusion while the impression material is

setting/polymerizing. The custom tray in this technique

is fabricated with an occlusion rim that allows the patient

to occlude on either an opposing occlusion rim or natural dentition. The impression is designed to capture the

tissues in a functional state. It has been shown that teeth

are in contact for less than 30 minutes each day,3 and

some suggest that it is difficult to rationalize a technique

that theoretically places the supporting tissues under

constant pressure when the mucosal tissues are in a functional state for only minutes per day.4,5 Dentures made

with a positive-pressure impression technique may

exhibit excellent initial retention, but alveolar ridge

resorption may be exacerbated by the pressure from

the denture, and the denture may loosen over a shorter

time period than would be anticipated with other techniques.4

The nonpressure or mucostatic technique records the

tissues in a nondisplaced, passive state.6 This impression

technique captures only nonmovable tissues and relies

on interfacial surface tension for retention. A metal denture base is recommended with this technique to ensure

intimate contact with the supporting tissues. The distortion of heat-polymerized PMMA does not allow for the

intimate tissue contact required to achieve adequate interfacial surface tension, yet this impression technique

remains popular.

Assistant Professor, Department of Prosthodontics and Operative

Dentistry.

b

Assistant Professor, Department of Prosthodontics and Operative

Dentistry.

c

Professor and Chairman, Department of Prosthodontics and

Operative Dentistry.

SEPTEMBER 2004

Fig. 1. Poor palatal adaptation is obvious on this processed

denture. Posterior aspect of cast has been trimmed to expose

lack of adaptation of denture base to palate; denture has not

been removed from cast.

The selective-pressure impression technique combines aspects of both techniques, as pressure is applied

to certain tissues while other areas are captured with

minimal pressure. This impression philosophy is

credited to Boucher5 and is based on a histologic understanding of the supporting tissues. Areas that are anatomically favorable to withstanding pressure, such as

the buccal surface of the maxillary alveolar process, lateral palate, or buccal shelf in the mandible, are loaded.

These areas are supported by dense cortical bone. The

rugae, midline raphe, mandibular alveolar ridge, and

areas of movable tissue are relieved because they do

not provide the same favorable anatomic quality for

withstanding functional load.

Each of the above philosophies considers how much

pressure will result in the most retentive, stable, and well

functioning denture; however, as long as the denture

base is processed with heat-polymerized PMMA, distortion can occur, resulting in a discrepancy between the

denture and palate. Denture bases fabricated from

heat-polymerized PMMA exhibit dimensional change

owing to volumetric shrinkage of as much as 6%.7 The

shrinkage of the resin results in a space between the palate and definitive cast as well as heavy pressure on the

lateral flange area (Fig. 1). This results in a denture

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY 299

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY

DUNCAN, RAGHAVENDRA, AND TAYLOR

Fig. 2. A, Typical maxillary denture processed with heat-polymerized PMMA with poor palatal contact as demonstrated with

disclosing paste. B, Maximum palatal adaptation of denture base using modified selective-pressure technique as demonstrated

with disclosing paste.

2.

3.

Fig. 3. Spacer wax is placed over entire anatomic area of cast

except in areas outlined. No tray relief is placed in those

areas.

base that does not contact the palate completely and thus

has less than ideal support, stability, and retention

(Fig. 2, A).

Various techniques have been described to minimize

or compensate for polymerization shrinkage of PMMA

through modification of the processing technique.

Some advocate modifying the definitive cast with holes

to anchor the acrylic resin during polymerization.8,9

Others have described a technique using high-expansion

dental stone to compensate for PMMA shrinkage.10 The

objective of this article is to describe a selective-pressure

impression technique that is intended to improve adaptation of the maxillary denture base by compensating for

polymerization shrinkage of the acrylic resin.

TECHNIQUE

1. Make a preliminary impression with irreversible

hydrocolloid and pour it in dental stone. Mark the

300

4.

5.

6.

borders of the custom tray 2 to 3 mm from the

mucobuccal fold to allow room for border molding.

Determine the posterior border of the tray by marking the vibrating line and hamular notches bilaterally.

Adapt 1 thickness of baseplate wax (Truwax;

Dentsply, York, Pa) to the cast to provide relief and

space for impression material. Laterally, cover the

alveolar ridges with spacer wax up to and including

the borders of the custom tray. End the spacer wax

at the posterior limit of the rugae. Place a narrow

band of wax along the midpalatal suture (Fig. 3).

Cut four 5 3 5-mm tissue stops out of the wax bilaterally in the canine and first molar regions. Place the

tissue stops slightly labial or buccal to the crest of the

ridge to assist in accurately seating the tray. Do

not cover the remaining portion of the palate; this

includes half to two thirds of the alveolar ridge, as

this area should contact the palatal tissues during

the definitive impression (Fig. 3).

Fabricate the custom tray with the material of choice,

with consideration for polymerization shrinkage and

distortion. Avoid light-polymerized resins as they

are relatively accurate but have a tendency to rebound

or pull away from the cast during manipulation and

polymerization. Use autopolymerizing PMMA resin

for the tray material to maximize tray accuracy.

At the definitive impression appointment, border

mold the custom tray with modeling plastic impression compound (Kerr Corp, Orange, Calif) or

other suitable material. Remove the spacer wax from

the tray before border molding is started. Remove

all wax residue to improve impression material

adhesion.

Make the definitive impression with a low-viscosity

impression material (Permlastic; Kerr Corp). No

vent holes are necessary in the tray but may be placed

over the ridge crest if desired. Use the 4 tissue stops

VOLUME 92 NUMBER 3

DUNCAN, RAGHAVENDRA, AND TAYLOR

in repositioning the tray accurately. Seat the tray

completely and place moderately heavy pressure in

the first molar region of the tray while the impression

material polymerizes.

7. Remove the impression from the patients mouth

and verify the presence of show-through in the areas

where no spacer wax was placed (Fig. 2, B).

8. Process the denture with a standard heat-processing

technique,11 finish, and polish.

9. Evaluate the denture intraorally, and note the adaptation of the denture base with pressure-indicating

paste (PIP; Mizzy, Cherry Hill, NJ). Relieve areas of

heavy show-through, such as the tissue stops. Verify

excellent adaptation to all the supporting tissues,

particularly those of the palate (Fig. 2, B).

DISCUSSION

This technique provides many of the same advantages

as the posterior palatal seal; however, it affords a much

larger contact area with the supporting tissues than does

the posterior palatal seal. By displacing the tissues of

the palate and effectively creating a deeper vault on the

definitive cast, the technique compensates for the

shrinkage of the PMMA. The result is a denture that

has improved contact with the palatal tissues. There

are no significant disadvantages to this technique. If

the denture base is evaluated with PIP and is found

to have excessive pressure, these areas can be easily

adjusted.

As an alternative to this impression technique, the

definitive cast could be adjusted by arbitrarily scraping

stone in the palatal vault. This would create an artificially deepened vault to compensate for polymerization

shrinkage comparable to carving a posterior palatal seal.

However, the impression technique described above is

a more controlled method for creating a similar result.

SEPTEMBER 2004

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY

SUMMARY

The selective-pressure impression technique described provides the clinician with a method for improving the palatal adaptation of maxillary complete

dentures fabricated with heat-polymerized PMMA.

REFERENCES

1. Latta GH, Bowles WF 3rd, Conkin JE. Three-dimensional stability of new

denture base resin systems. J Prosthet Dent 1990;63:654-61.

2. Lechner SK, Lautenschlager EP. Processing changes in maxillary complete

dentures. J Prosthet Dent 1984;52:20-4.

3. Graf H. Bruxism. Dent Clin North Am 1969;13:659-65.

4. el-Khodary NM, Shaaban NA, Abdel-Hakim AM. Effect of complete denture impression technique on the oral mucosa. J Prosthet Dent 1985;53:

543-9.

5. Boucher C. Complete denture impressions based on the anatomy of the

mouth. J Am Dent Assoc 1944;31:17-24.

6. Addison I. Mucostatic impression. J Am Dent Assoc 1944;31:941-50.

7. Craig R. Restorative dental materials. 11th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002.

p. 647.

8. Laughlin GA, Eick JD, Glaros AG, Young L, Moore DJ. A comparison of

palatal adaptation in acrylic resin denture bases using conventional and

anchored polymerization techniques. J Prosthodont 2001;10:204-11.

9. Polyzois GL. Improving the adaptation of denture bases by anchorage to

the casts: a comparative study. Quintessence Int 1990;21:185-90.

10. Sykora O, Sutow EJ. Posterior palatal seal adaptation: influence of high expansion stone. J Oral Rehabil 1996;23:342-5.

11. Zarb GA, Bolender CL, Carlsson G, Boucher CO. Bouchers prosthodontic

treatment for edentulous patients. 11th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 1997. p.

332-46.

Reprint requests to:

DR JACQUELINE P. DUNCAN

DEPARTMENT OF PROSTHODONTICS

UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT HEALTH CENTER

FARMINGTON, CT 06030-1615

FAX: 860-679-1370

E-MAIL: jduncan@nso2.uchc.edu

0022-3913/$30.00

Copyright 2004 by The Editorial Council of The Journal of Prosthetic

Dentistry

doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.06.001

301

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Handbook5 PDFDocumento257 páginasHandbook5 PDFZAKROUNAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Virtual Work 3rd Year Structural EngineeringDocumento129 páginasVirtual Work 3rd Year Structural EngineeringStefano Martin PorciunculaAinda não há avaliações

- Centrifugal CastingDocumento266 páginasCentrifugal Castinguzairmetallurgist100% (2)

- Jet Bit Nozzle Size SelectionDocumento46 páginasJet Bit Nozzle Size SelectionBharat BhattaraiAinda não há avaliações

- Control System (136-248) PDFDocumento113 páginasControl System (136-248) PDFmuruganAinda não há avaliações

- Lightweight UavDocumento149 páginasLightweight Uavvb corpAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To XAFSDocumento270 páginasIntroduction To XAFSEric William CochranAinda não há avaliações

- Thermal Analysis of Albendazole Investigated by HSM, DSC and FTIRDocumento8 páginasThermal Analysis of Albendazole Investigated by HSM, DSC and FTIRElvina iskandarAinda não há avaliações

- Orthodontic Extrusion of Premolar Teeth - An Improved TechniqueDocumento6 páginasOrthodontic Extrusion of Premolar Teeth - An Improved TechniquejorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Soft Tissues Remodeling Technique As A N PDFDocumento12 páginasSoft Tissues Remodeling Technique As A N PDFjorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Moraschini 2015Documento11 páginasMoraschini 2015jorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Abutment Tooth Color, Cement Color, and Ceramic Thickness On The Resulting Optical Color of A CAD: CAM Glass-Ceramic Lithium Disilicate - Reinforced Crown PDFDocumento8 páginasEffect of Abutment Tooth Color, Cement Color, and Ceramic Thickness On The Resulting Optical Color of A CAD: CAM Glass-Ceramic Lithium Disilicate - Reinforced Crown PDFjorgeAinda não há avaliações

- 7 Study of The Acceptability of Lateral Interocclusal Records by A Modular ArticulatorDocumento4 páginas7 Study of The Acceptability of Lateral Interocclusal Records by A Modular ArticulatorjorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of The Marginal and Internal Discrepancies of CAD:CAM Endocrowns With Different Cavity Depths - An in Vitro StudyDocumento7 páginasEvaluation of The Marginal and Internal Discrepancies of CAD:CAM Endocrowns With Different Cavity Depths - An in Vitro StudyjorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Ahmed Et Al-2016-Journal of Esthetic and Restorative DentistryDocumento3 páginasAhmed Et Al-2016-Journal of Esthetic and Restorative DentistryAdrian YohanesAinda não há avaliações

- Grossmann2005 PDFDocumento4 páginasGrossmann2005 PDFjorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Imburgia DSD PosterDocumento1 páginaImburgia DSD PosterjorgeAinda não há avaliações

- BFEP2Documento6 páginasBFEP2jorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Gingival Zenith Positions and Levels of The MaxillaryDocumento9 páginasGingival Zenith Positions and Levels of The MaxillaryNia AlfaroAinda não há avaliações

- Bidra '13Documento18 páginasBidra '13jorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Experimental Birefringence Photography in DentistryDocumento12 páginasExperimental Birefringence Photography in Dentistryjorge100% (1)

- Dr. Mezmer's Psychopedia of Bad PsychologyDocumento378 páginasDr. Mezmer's Psychopedia of Bad PsychologyArt Marr100% (5)

- Modeling Mantle Convection CurrentsDocumento3 páginasModeling Mantle Convection Currentsapi-217451187Ainda não há avaliações

- Amateur's Telescope Was First Published in 1920. However, Unlike Ellison's TimeDocumento4 páginasAmateur's Telescope Was First Published in 1920. However, Unlike Ellison's Timemohamadazaresh0% (1)

- Lab Instruments GuideDocumento19 páginasLab Instruments GuideDesQuina DescoAinda não há avaliações

- Direct Determination of The Flow Curves of NoDocumento4 páginasDirect Determination of The Flow Curves of NoZaid HadiAinda não há avaliações

- Offshore Pipeline Hydraulic and Mechanical AnalysesDocumento25 páginasOffshore Pipeline Hydraulic and Mechanical AnalysesEslam RedaAinda não há avaliações

- Levee Drain Analysis in SlideDocumento12 páginasLevee Drain Analysis in SlideAdriRGAinda não há avaliações

- MechanicsDocumento558 páginasMechanicsfejiloAinda não há avaliações

- Hiad 2Documento15 páginasHiad 2Hrishikesh JoshiAinda não há avaliações

- Abaqus Analysis User's Manual, 32.15 (User Elements)Documento22 páginasAbaqus Analysis User's Manual, 32.15 (User Elements)Elias BuAinda não há avaliações

- NCHRP RPT 242 PDFDocumento85 páginasNCHRP RPT 242 PDFDavid Drolet TremblayAinda não há avaliações

- Mapua Institute of Technology: Field Work 1 Pacing On Level GroundDocumento7 páginasMapua Institute of Technology: Field Work 1 Pacing On Level GroundIan Ag-aDoctorAinda não há avaliações

- Electrostatic Discharge Ignition of Energetic MaterialsDocumento9 páginasElectrostatic Discharge Ignition of Energetic Materialspamos1111Ainda não há avaliações

- Electrical Conductivity of Carbon Blacks Under CompressionDocumento7 páginasElectrical Conductivity of Carbon Blacks Under CompressionМирослав Кузишин100% (1)

- JEE Class Companion Physics: Module-9Documento227 páginasJEE Class Companion Physics: Module-9RupakAinda não há avaliações

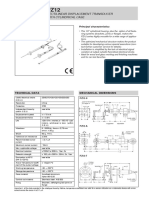

- Rectilinear Displacement Transducer With Cylindrical Case: Technical Data Mechanical DimensionsDocumento2 páginasRectilinear Displacement Transducer With Cylindrical Case: Technical Data Mechanical Dimensionsl561926Ainda não há avaliações

- Cara SamplingDocumento8 páginasCara SamplingAngga Dwi PutrantoAinda não há avaliações

- Design Steel Compression MembersDocumento42 páginasDesign Steel Compression MembersFayyazAhmadAinda não há avaliações

- M.Prasad Naidu MSC Medical Biochemistry, PH.D Research ScholarDocumento31 páginasM.Prasad Naidu MSC Medical Biochemistry, PH.D Research ScholarDr. M. Prasad NaiduAinda não há avaliações

- Name: Teacher: Date: Score:: Identify The Properties of MathematicsDocumento2 páginasName: Teacher: Date: Score:: Identify The Properties of MathematicsMacPapitaAinda não há avaliações

- Modeling Arterial Blood Flow With Navier-StokesDocumento15 páginasModeling Arterial Blood Flow With Navier-Stokesapi-358127907100% (1)

- Renewableand Sustainable Energy ReviewsDocumento9 páginasRenewableand Sustainable Energy Reviewssundeep sAinda não há avaliações