Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Stan Allen Villa VPRO

Enviado por

Yong Feng SeeDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Stan Allen Villa VPRO

Enviado por

Yong Feng SeeDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Yong Feng See

ARCH 572

Section 6 (Abrahamson)

Paper STRUCTURES: Stan Allen, Villa VPRO

This paper analyses Stan Allens review of MVRDVs Villa VPRO, a building for the

headquarters of the VPRO broadcasting company in Hilversum, the Netherlands, and

compares it to Piet Stams review of the same building as well as Allens own review of Le

Corbusiers Carpenter Center. While Stam analyses the building from the idea of the

classical villa and how it is transformed and evolved by MVRDV, Allen is more concerned

with the how of MVRDVs design methods rather than the building itself. In other words,

Allen approaches the building from an ideological point of view while Stam uses a more

phenomenological and analytical approach. Allens review of the Carpenter Center similarly

reflects this concern for how and why choices were made in its design. Ideology is

something that Loos utilizes heavily in his parable of the Poor Little Rich Man where his

fictional architect sees his role as to design the complete living environment. Loos uses this

to argue against this type of total design, while Allen applies it in the converse to describe

MVRDVs work as landscapes that are open to change. This comparison suggests that the

lens of ideology can be a powerful tool for analyzing buildings beyond their surface

appearances to uncover the modes of design and practice that are operating behind the

scenes.

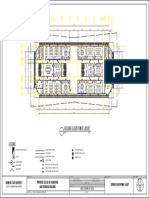

Allens review of the Villa VPRO appears after a short description of the building, in

which its architects emphasize both an office landscape approach as well a desire to

work on and exhibit problems of information and data. The drawings and diagrams that

accompany show the voids that make up this landscape, as well as the multiple layers of

systems superimposed on the plan. Allens review itself is titled Artificial Ecology: An

Editorial Postscript, indicating both an interpretation of MVRDVs working method from a

biological perspective, as well as a desire to both add on to and comment on MVRDVs

description. Allen characterizes MVRDVs approach as one of radical pragmatism, where

a stubborn insistence to working rationally through data, but not through conventional

design methods, results in uniquely unexpected outcomes (Allen 108). The artificial ecology

Yong Feng See

ARCH 572

Section 6 (Abrahamson)

of the title is its result, where the unpredictable needs of the client necessitated a building

that could be flexible and open to growth and change, even after the building is

constructed.

Piet Stams review begins with VPROs wish to have the new building evoke the villa

atmosphere of its old offices. He spends most of the review walking the reader into the

building through a detailed description of the spatial sequences and experiences, which is

supported by large photos that show the wide variety of villa-like spaces in the building.

Stam compares the building to Herman Hertzbergers Centraal Beheer and argues that the

latters repetitive spaces allow individuals to claim their own territories within the building,

while the Villa VPRO restricts such appropriation, instead offering varied spaces to move

through, creating ones own narrative.

Though both reviews are of the same building, they differ greatly in their methods of

describing the building, the key concepts used, and their analysis of what is significant in

each building. Stam takes a clearly phenomenological approach that prioritizes the spatial,

visual and tactile experience of physically walking through the building, while also

connecting it to the concept of the villa and historical precedent. Allen, on the other hand,

does not reference any specific building element or space in the building in his review. He

is instead more interested in the architects working method and how it differs from the

conventional practice of architecture. However, Allen also seems to project his own

interests onto his interpretation of the building. Though published two years after the

review, Allens concept of infrastructural urbanism is almost exactly the same as the

artificial ecology that he uses to describe the Villa VPRO (Allen, Infrastructural

Urbanism). It also goes further than MVRDVs own report which uses the term

landscape to describe the blurring of interior and exterior in terms of space and

topography, but not in the biological sense of a framework for change that Allen interprets.

As a widely published architect and influential voice of landscape urbanism, Allen brings in

much more of his own ideas into the review compared to Stam, whose descriptions of the

Yong Feng See

ARCH 572

Section 6 (Abrahamson)

spatial sequences are more objective in the sense that he does not use them to further any

larger thesis about what the building is.

Allens interest in the practice of architecture is made clear in his introduction to

the book Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation. Here he criticizes a dumb

practice that fits itself into the boundaries of codes and conventions, and advocates for a

pragmatic realism where the limits are found not through an analysis of the past, but

from a material practice that mediates between abstraction and matter (Allen,

Introduction xviii). This is strikingly similar to the working method of MVRDV that he

praises in his review. In addition, Allen also argues that architecture should be understood

through the emergence of ideas in and through the materials and procedures of the

architectural work itself, and that writing about architecture should help to clarify this

process (Allen xxiv). Thus, Allen believes that writing should not simply describe or analyze

in reference to established conventions but uncover thought processes in order to open up

new ways of practice.

Such an approach can be seen in Allens review of a different building: Le

Corbusiers Carpenter Center. Here, he analyses the building through the lenses of

Modernism and movement, and how the building fits into those ideologies. Though Allen

begins the review with a walkthrough of its entrance like Stam, he uses it to introduce the

concept of movement and how other architects and theorists have dealt with it, thus

opening the review to a whole other string of references and resources. He then goes into

detail about possible influences and processes on Le Corbusier in creating this movementimage, such as his cardboard cuts and his imagined choreography of the sound and

movement (Allen 107, 111). Similar to how the modern phenomenon of datascapes is a key

influence in MVRDVs practice, Allen identifies the influence of film, mathematics and

Deleuzes any-instant-whatever in Le Corbusiers design. The second half of the review

focuses on the use of reinforced concrete, where the physical realities of construction and

Yong Feng See

ARCH 572

Section 6 (Abrahamson)

climate are strategically manipulated in service of lightness and movement, for example in

the flat slabs without beams or capitals, and the smooth finishes of the concrete.

Allens review of the Carpenter Center is much longer than that of the Villa VPRO

and more detailed, perhaps due to the historical perspective of writing a few decades after

its completion in comparison to the latter, which was written contemporaneously. Allen also

does not try to fit in his ideas of landscape and infrastructure into his interpretation of Le

Corbusier, but instead draws in related thinkers and ideologies of his time in order to plot

out the background of ideas influencing Le Corbusiers design intentions. Thus, both

reviews still align to his position on practice and criticism as mentioned above. They do not

try to describe their subjects in a comprehensive manner that describes the experience of

every space and detail, but focus on the key points where the architects intention and

material reality collide to give a unique result the moment when ideologies, whether that

of Modernist movement, information or landscape, negotiate with the realities of the world

in a performative practice (Allen, Introduction xxiii).

Ideology plays a big role in the analysis of any work of architecture. In Adolf Loos

parable of the Poor Little Rich Man, the ideology of the gesamtkunstwerk traps the man

into a situation where everything has been decided for him, symbolizing the power of ideas

over materials or spaces. Although Loos argument was made in the context of the

excessive ornamentation of the Vienna Secession and the need for self-expression, Stam

raises the same issue in pointing out how each space in the Villa VPRO has been carefully

and uniquely designed, to the point that the faade that expresses these differences has

thirty-five different types of glazing, leaving no space for individual expression. However,

Allen sees the Villa VPRO as the reverse: much more amenable and open to user

improvisation (Allen, Villa VPRO 34). Here it is impossible to determine which view is

right, perhaps suggesting that while an ideological lens can be a useful way to explore the

architects mode of practice, the actual performance of the building according to its

Yong Feng See

ARCH 572

Section 6 (Abrahamson)

ideology will depend on how its users actually inhabit and occupy it, where ideas make the

leap into reality.

Bibliography

Allen, Stan. Villa VPRO. Assemblage (no.34 December 1997): 92-109.

Allen, Stan. Infrastructural Urbanism. In Points + Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the

City. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. 1999: 46-57.

Allen, Stan. Le Corbusier and Modernist Movement. In Practice: Architecture, Technique

and Representation, 42-47. Australia: G B Arts International, 2000.

Allen, Stan. Introduction: Practice vs. Project. In Practice: Architecture, Technique and

Representation, xiii-xxv. Australia: G B Arts International, 2000.

Loos, Adolf. The Poor Little Rich Man. In Spoken into the Void: Collected Essays, 18971900, 125-127. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982.

Stam, P. (1999). Villa VPRO. The Architectural Review, 205(1225): 38-44.

Você também pode gostar

- Rural Architecture: Being a Complete Description of Farm Houses, Cottages, and Out BuildingsNo EverandRural Architecture: Being a Complete Description of Farm Houses, Cottages, and Out BuildingsAinda não há avaliações

- Archipelagos PDFDocumento67 páginasArchipelagos PDFSimona DimitrovskaAinda não há avaliações

- Architectural Philosophy - SesionalDocumento7 páginasArchitectural Philosophy - SesionalAr AmirAinda não há avaliações

- Site Specific + ContextualismDocumento5 páginasSite Specific + ContextualismAristocrates CharatsarisAinda não há avaliações

- Constructions: An Experimental Approach to Intensely Local ArchitecturesNo EverandConstructions: An Experimental Approach to Intensely Local ArchitecturesAinda não há avaliações

- From Typology To Hermeneutics in Architectural DesignDocumento15 páginasFrom Typology To Hermeneutics in Architectural DesignOrangejoeAinda não há avaliações

- Gothic Art and ArchitectureDocumento108 páginasGothic Art and ArchitectureJ VAinda não há avaliações

- FunctionalismDocumento3 páginasFunctionalismClearyne Banasan100% (1)

- Shadrach Woods and The Architecture of Everyday UrbanismDocumento40 páginasShadrach Woods and The Architecture of Everyday UrbanismAngemar Roquero MirasolAinda não há avaliações

- Architecture School Three Centuries of Educating Architects in North AmericaDocumento2 páginasArchitecture School Three Centuries of Educating Architects in North AmericakimAinda não há avaliações

- Habraken - Questions - That - Wont - Go - Away PDFDocumento8 páginasHabraken - Questions - That - Wont - Go - Away PDFKnot NairAinda não há avaliações

- Order Is, KahnDocumento2 páginasOrder Is, KahnRick De La Cruz100% (1)

- 4ylej Santiago Calatrava Conversations With StudentsDocumento112 páginas4ylej Santiago Calatrava Conversations With StudentsMacrem Macrem100% (1)

- A City Is Not A Tree CompletDocumento31 páginasA City Is Not A Tree CompletIoana BreazAinda não há avaliações

- Architecture As Conceptual ArtDocumento5 páginasArchitecture As Conceptual ArtIoana MarinAinda não há avaliações

- Design Framework Study in Stretto HouseDocumento3 páginasDesign Framework Study in Stretto HouseHutari Maya RiantyAinda não há avaliações

- Woods, Shadrach - What U Can DoDocumento23 páginasWoods, Shadrach - What U Can DoimarreguiAinda não há avaliações

- Preserving Postmodern ArchitectureDocumento123 páginasPreserving Postmodern ArchitectureakhilaAinda não há avaliações

- The Beauty of Beaux-Arts Pioneers of TheDocumento9 páginasThe Beauty of Beaux-Arts Pioneers of Thehappynidhi86Ainda não há avaliações

- 1-2 Regionalism and Identity PDFDocumento36 páginas1-2 Regionalism and Identity PDFOmar BadrAinda não há avaliações

- The City As A Project - Underground Observatories - On Marot's Palympsestuos IthacaDocumento3 páginasThe City As A Project - Underground Observatories - On Marot's Palympsestuos IthacammrduljasAinda não há avaliações

- The Big Rethink - Farewell To ModernismDocumento14 páginasThe Big Rethink - Farewell To ModernismJames Irvine100% (1)

- Architecture As Representation. Notes On Álvaro Siza's AnthropomorphismDocumento22 páginasArchitecture As Representation. Notes On Álvaro Siza's AnthropomorphismWojciech PszoniakAinda não há avaliações

- Ankone, Joost 1Documento120 páginasAnkone, Joost 1Sidra JaveedAinda não há avaliações

- On Reading Architecture Gandelsonas MortonDocumento16 páginasOn Reading Architecture Gandelsonas Mortonjongns100% (1)

- Catalan ArchitectureDocumento12 páginasCatalan ArchitectureReeve Roger RoldanAinda não há avaliações

- The Question of Identity in Malaysian ArchitectureDocumento11 páginasThe Question of Identity in Malaysian ArchitectureMyra Elisse M. AnitAinda não há avaliações

- F "T C R ": 3. Critical Regionalism and World CultureDocumento6 páginasF "T C R ": 3. Critical Regionalism and World CultureAnna BartkowskaAinda não há avaliações

- Toyo Ito Calls The Sendai MediathequeDocumento4 páginasToyo Ito Calls The Sendai MediathequehariAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 2: Fundamentals of ArchitectureDocumento65 páginasUnit 2: Fundamentals of ArchitectureMary Jessica UyAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Projetcs On Typology - MoneoDocumento22 páginas3 Projetcs On Typology - MoneoRuxandra VasileAinda não há avaliações

- Autonomous Architecture in Flanders PDFDocumento13 páginasAutonomous Architecture in Flanders PDFMałgorzata BabskaAinda não há avaliações

- 2018 TheMathematicsOfThe - 5 Mies Van Der Rohe Caracteristics of The Free PlanDocumento51 páginas2018 TheMathematicsOfThe - 5 Mies Van Der Rohe Caracteristics of The Free Planvinicius carriãoAinda não há avaliações

- 5888 19405 1 SM PDFDocumento17 páginas5888 19405 1 SM PDFMiguel Botero VilladaAinda não há avaliações

- James Stirling - Le Corbusier's Chapel and The Crisis of RationalismDocumento7 páginasJames Stirling - Le Corbusier's Chapel and The Crisis of RationalismClaudio Triassi50% (2)

- Ais Final Report 1Documento28 páginasAis Final Report 1Khusboo ThapaAinda não há avaliações

- Urban Design SampleDocumento15 páginasUrban Design SampleJawms DalaAinda não há avaliações

- New City Spaces by Jan Gehl Lars Gemze 8774072935Documento5 páginasNew City Spaces by Jan Gehl Lars Gemze 8774072935Tanya BholaAinda não há avaliações

- Tel Aviv. Preserving The ModernDocumento13 páginasTel Aviv. Preserving The ModernCarlotaAinda não há avaliações

- Johnson Museum of Art - Analysis PosterDocumento1 páginaJohnson Museum of Art - Analysis PosterlAinda não há avaliações

- Charles CorreaDocumento11 páginasCharles CorreaMrigank VatsAinda não há avaliações

- Robert VenturiDocumento14 páginasRobert VenturiUrvish SambreAinda não há avaliações

- Great Mosque of AlgiersDocumento1 páginaGreat Mosque of AlgiersAbdelbasset HedhoudAinda não há avaliações

- Bolles + Wilson + Pni2001Documento36 páginasBolles + Wilson + Pni2001Atelier AlbaniaAinda não há avaliações

- (Routledge Research in Architecture) J. Kevin Story - The Complexities of John Hejduk's Work - Exorcising Outlines, Apparitions and Angels-Routledge (2020)Documento257 páginas(Routledge Research in Architecture) J. Kevin Story - The Complexities of John Hejduk's Work - Exorcising Outlines, Apparitions and Angels-Routledge (2020)Ana Isabel Palacio SanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Barragan & KahnDocumento12 páginasBarragan & KahnAmantle Bre PelaeloAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review - History 3200Documento6 páginasLiterature Review - History 3200Frank MaguiñaAinda não há avaliações

- 02 Eisenman Cardboard ArchitectureDocumento12 páginas02 Eisenman Cardboard Architecturebecha18Ainda não há avaliações

- Vol14 Stephen PoonDocumento24 páginasVol14 Stephen PoonZâïñåb Hïñä IrfâñAinda não há avaliações

- DiagramsDocumento38 páginasDiagramsManimegalai PrasannaAinda não há avaliações

- Serpentine Pavilion Press PackDocumento21 páginasSerpentine Pavilion Press PackAlvaro RosaDayerAinda não há avaliações

- On Meaning-Image Coop Himmelb L Au ArchiDocumento7 páginasOn Meaning-Image Coop Himmelb L Au ArchiLeoCutrixAinda não há avaliações

- Le CorbusierDocumento30 páginasLe CorbusierSoumyaAinda não há avaliações

- Keerthana A - 810115251019Documento44 páginasKeerthana A - 810115251019Ashwin RamkumarAinda não há avaliações

- History of Architecture 1Documento22 páginasHistory of Architecture 1Mike XrossAinda não há avaliações

- A Typology of Building FormsDocumento30 páginasA Typology of Building FormsSheree Nichole GuillerganAinda não há avaliações

- Saverio Muratori Towards A Morphological School of Urban DesignDocumento14 páginasSaverio Muratori Towards A Morphological School of Urban Design11Ainda não há avaliações

- Villa VPRO PDFDocumento3 páginasVilla VPRO PDFCamilo Esteban Ponce De León RiquelmeAinda não há avaliações

- SanitaryDocumento4 páginasSanitaryHarris FadlillahAinda não há avaliações

- Structure II: Course Code: ARCH 209Documento29 páginasStructure II: Course Code: ARCH 209layaljamal2Ainda não há avaliações

- AASTMT - Vernacular Architecture in EgyptDocumento104 páginasAASTMT - Vernacular Architecture in Egyptshaimaa.ashour87% (15)

- الانظمة الانشائية للاسقفDocumento63 páginasالانظمة الانشائية للاسقفMaha Ezz EldeenAinda não há avaliações

- CardB HouseDocumento29 páginasCardB Housemd2b187Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter 5 Insulation Materials and TechniquesDocumento29 páginasChapter 5 Insulation Materials and TechniquesMd Rodi BidinAinda não há avaliações

- BHP - Talisa - Simplified Brochure - Aug23Documento7 páginasBHP - Talisa - Simplified Brochure - Aug23stanleynsmAinda não há avaliações

- FLASH - Resilient Design Guide PDFDocumento48 páginasFLASH - Resilient Design Guide PDFbradley_waltersAinda não há avaliações

- SlipformDocumento18 páginasSlipformSunetra DattaAinda não há avaliações

- Vernacular Architecture. BALAG, PIA DEANNE M.Documento10 páginasVernacular Architecture. BALAG, PIA DEANNE M.Julia May BalagAinda não há avaliações

- HB 195-2002 The Australian Earth Building HandbookDocumento11 páginasHB 195-2002 The Australian Earth Building HandbookSAI Global - APAC50% (10)

- E1 Ground Floor Power LayoutDocumento1 páginaE1 Ground Floor Power LayoutMark Anthony Mores FalogmeAinda não há avaliações

- Evolution in KitchenDocumento33 páginasEvolution in KitchennidhisutharAinda não há avaliações

- Kawneer Trifab 400Documento5 páginasKawneer Trifab 400WillBuckAinda não há avaliações

- American Architect and Architecture 1000000626Documento778 páginasAmerican Architect and Architecture 1000000626Olya Yavi100% (2)

- 11th Floor Plan 09102019 FCD PDFDocumento10 páginas11th Floor Plan 09102019 FCD PDFRhoderick MiqueAinda não há avaliações

- Masters of Architecture Reviewer OneDocumento3 páginasMasters of Architecture Reviewer OneJamil EsteronAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 8 - Form Scaffolding and StagingDocumento7 páginasLesson 8 - Form Scaffolding and StagingROMNICK HANDAYANAinda não há avaliações

- NCDE RYD NBS XX SP A F31 - Precast Concrete Sills Lintels Copings Features - Construction - C1Documento5 páginasNCDE RYD NBS XX SP A F31 - Precast Concrete Sills Lintels Copings Features - Construction - C1johnAinda não há avaliações

- CLC Project ReportDocumento11 páginasCLC Project ReportMahadeo0% (2)

- Quikrete Concrete Product GuideDocumento28 páginasQuikrete Concrete Product GuideBurak Yanar100% (1)

- Trabajo Final de InglesDocumento8 páginasTrabajo Final de InglesFernanda ChAinda não há avaliações

- National Housing Loans: Bill of QuantitiesDocumento5 páginasNational Housing Loans: Bill of QuantitieskhajaAinda não há avaliações

- ATANUDocumento1 páginaATANUAsimAinda não há avaliações

- The Chrysler BuildingDocumento12 páginasThe Chrysler Buildingapi-320157649Ainda não há avaliações

- 27,30 - The Saudi Building Code (SBC) - PDF - 71-71Documento1 página27,30 - The Saudi Building Code (SBC) - PDF - 71-71heshamAinda não há avaliações

- Sheet No. Description Scale Sheet No. Description Scale Sheet No. Description ScaleDocumento1 páginaSheet No. Description Scale Sheet No. Description Scale Sheet No. Description ScaleAnonymous qOBFvIAinda não há avaliações

- Section - Doors and WindowsDocumento1 páginaSection - Doors and WindowsLalisa MAinda não há avaliações

- ACD Proposed 4 Storey With Roof Deck BuildingDocumento13 páginasACD Proposed 4 Storey With Roof Deck BuildingChristian Lloyd EspinozaAinda não há avaliações

- Dome of Florence CathedralDocumento2 páginasDome of Florence CathedralSARANSH GUPTAAinda não há avaliações

- The Art of LEGO Construction: New York City Brick by BrickNo EverandThe Art of LEGO Construction: New York City Brick by BrickAinda não há avaliações

- House Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetNo EverandHouse Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetAinda não há avaliações

- Building Structures Illustrated: Patterns, Systems, and DesignNo EverandBuilding Structures Illustrated: Patterns, Systems, and DesignNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (4)

- A Place of My Own: The Architecture of DaydreamsNo EverandA Place of My Own: The Architecture of DaydreamsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (242)

- Dream Sewing Spaces: Design & Organization for Spaces Large & SmallNo EverandDream Sewing Spaces: Design & Organization for Spaces Large & SmallNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (24)

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisNo EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (49)

- Problem Seeking: An Architectural Programming PrimerNo EverandProblem Seeking: An Architectural Programming PrimerNota: 2 de 5 estrelas2/5 (1)

- Martha Stewart's Organizing: The Manual for Bringing Order to Your Life, Home & RoutinesNo EverandMartha Stewart's Organizing: The Manual for Bringing Order to Your Life, Home & RoutinesNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (11)

- Fundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and MethodsNo EverandFundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and MethodsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (3)

- Flying Star Feng Shui: Change Your Energy; Change Your LuckNo EverandFlying Star Feng Shui: Change Your Energy; Change Your LuckNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (2)

- Vastu: The Ultimate Guide to Vastu Shastra and Feng Shui Remedies for Harmonious LivingNo EverandVastu: The Ultimate Guide to Vastu Shastra and Feng Shui Remedies for Harmonious LivingNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (41)

- Architectural Detailing: Function, Constructibility, AestheticsNo EverandArchitectural Detailing: Function, Constructibility, AestheticsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Ancient Greece: An Enthralling Overview of Greek History, Starting from the Archaic Period through the Classical Age to the Hellenistic CivilizationNo EverandAncient Greece: An Enthralling Overview of Greek History, Starting from the Archaic Period through the Classical Age to the Hellenistic CivilizationAinda não há avaliações

- Advanced OSINT Strategies: Online Investigations And Intelligence GatheringNo EverandAdvanced OSINT Strategies: Online Investigations And Intelligence GatheringAinda não há avaliações

- Extraordinary Projects for Ordinary People: Do-It-Yourself Ideas from the People Who Actually Do ThemNo EverandExtraordinary Projects for Ordinary People: Do-It-Yourself Ideas from the People Who Actually Do ThemNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)

- Home Style by City: Ideas and Inspiration from Paris, London, New York, Los Angeles, and CopenhagenNo EverandHome Style by City: Ideas and Inspiration from Paris, London, New York, Los Angeles, and CopenhagenNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (3)

- Big Bim Little Bim: the Practical Approach to Building Information Modeling - Integrated Practice Done the Right Way!No EverandBig Bim Little Bim: the Practical Approach to Building Information Modeling - Integrated Practice Done the Right Way!Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (4)

- PMP Exam Code Cracked: Success Strategies and Quick Questions to Crush the TestNo EverandPMP Exam Code Cracked: Success Strategies and Quick Questions to Crush the TestAinda não há avaliações

- The Year-Round Solar Greenhouse: How to Design and Build a Net-Zero Energy GreenhouseNo EverandThe Year-Round Solar Greenhouse: How to Design and Build a Net-Zero Energy GreenhouseNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- The Florentines: From Dante to Galileo: The Transformation of Western CivilizationNo EverandThe Florentines: From Dante to Galileo: The Transformation of Western CivilizationNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (11)

- How to Learn Home Improvement Skills: A Comprehensive GuideNo EverandHow to Learn Home Improvement Skills: A Comprehensive GuideAinda não há avaliações

- Site Analysis: Informing Context-Sensitive and Sustainable Site Planning and DesignNo EverandSite Analysis: Informing Context-Sensitive and Sustainable Site Planning and DesignNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)