Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Where Are The Accounting Professors?: Journal of College Teaching & Learning - January 2008 Volume 5, Number 1

Enviado por

itn_ntiDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Where Are The Accounting Professors?: Journal of College Teaching & Learning - January 2008 Volume 5, Number 1

Enviado por

itn_ntiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of College Teaching & Learning January 2008

Volume 5, Number 1

Where Are the Accounting Professors?

Jui-Chin Chang, (Email: cjchang40@yahoo.com), Morgan State University

Huey-Lian Sun, (Email: hsun@jewel.morgan.edu), Morgan State University

ABSTRACT

Accounting education is facing a crisis of shortage of accounting faculty. This study discusses the

reasons behind the shortage and offers suggestions to increase the supply of accounting faculty.

Our suggestions are as followings. First, educators should begin promoting accounting academia

as one of the career choices to undergraduate and graduate students. Second, schools should

provide adequate financial support to Ph.D. students. Third, academic administers should

encourage facultys involvement in mentoring Ph.D. students. Finally, the tenure and promotion

system needs to be reevaluated to facilitate success in faculty development.

ust before Enron, WorldCom and other accounting scandals, Albrecht and Sack (2000) cast doubts on the

future of accounting education. They quoted the AICPAs supply-and-demand reports to support their

allegation that fewer and less qualified students were choosing accounting as a major. They argued that

students perceived accountants to be incompatible with the creative, rewarding and people-oriented careers that

many students envisioned for themselves. They also contributed the problem of declining enrollment to poorly

designed accounting programs that were not attractive to students and did not meet the demand of accounting

professionals. Even before the report of Albrecht and Sack (2000), many institutions and studies have devoted

resources to increase accounting enrollment in order to meet the demand of the accounting profession and to

survive.1,2 They often emphasized on attracting the best and brightest students into the accounting profession.

However, they failed to recognize that inspiring and passionate professors are the keys to attract the best and

brightest students. Unfortunately, the accounting education in recent years has encountered a serious shortage of

qualified faculty. The shortage came at a time when studies have just reported a stable increase in accounting

enrollment.3 In the near future, accounting education might face a crisis that there are not enough qualified

accounting faculty to teach the best and brightest students attracted to the programs.

Some studies have provided insight on the shortage of qualified accounting faculty from the demand and

supply of future faculty. Carpenter and Robin (2004) reported that the doctoral program output in accounting has

declined to 110 in 2002 when it compared with an average approximately 200 per year in the late 1980s through

mid-1990s. Gullapalli (2004) reported that the number of accounting faculty openings was more than twice in the

number of submitted resumes in 2002. The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB)

estimated the faculty shortage including accounting in the United States to reach 1,142 individuals by 2008, and

2,419 by 2013.4 Plumlee, Kachelmeier, Madeo, Pratt, and Drull (2006) reported similar prediction of an overall

shortage of accounting faculty.

For instance, in 1994, the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA) and the Financial Executives Institute (FEI) sought for

What Corporate America Wants in Entry-Level Accountant from the customer perspective. In 1998, the American Accounting

Association (AAA) urged each institution to define its market niche in order to build new curricula in the high priority areas. The

IMAs 1999 Counting More, Counting Less outlined the transformations in the management accounting profession.

2

Bedford Commission (1986) stated that accounting education was not meeting the needs of changing profession (Friedlan,

1995). Inman, Wenzler, and Wickert (1989) warned that the accounting majors did not attract the right type of students. The

Accounting Education Change Commission (AECC) was appointed by the American Accounting Association and supported by

the Big Eight (then) public accounting firms in 1989 when the White Paper: Perspectives on Education was published. Its

Position Statement Number One addressed the objectives of accounting.

3

Titard, Braun and Meyer (2004) and Gullapalli (2004) reported that there was contrary evidence to the previous concern about

losing accounting students due to the accounting scandals. In fact, students gained a deeper understanding of accounting matters

and its implication of the profession after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the economy downturn.

4

Rayburn, J. (2005). Retrieved from http://aaahq.org/AM2005/menu.htm/2005_Rayburn.ppt.

47

Journal of College Teaching & Learning January 2008

Volume 5, Number 1

The purpose of this study is to examine reasons for the shortage of accounting faculty from both the

demand and supply perspectives and offer suggestions to reverse the trend of shortage with emphasis on increasing

the supply of qualified accounting faculty.

SHORTAGE OF ACCOUNTING FACULTY: FROM THE DEMAND PERSPECTIVE

There are many factors which induced an increasing demand for accounting faculty. First, although critics

has criticized the 150-hour requirement that hindered the enrollment of undergraduates, it could result in an increase

in the number of accounting courses taught, and subsequently an increase in the demand for accounting faculty

(Campbell et al, 1990). Many universities now offer 5-year accounting programs for students to get both

undergraduate and master degrees in five years to meet the 150-hour requirement. Accordingly, more accounting

faculty members are needed for the additional accounting courses.

Second, the prevailing trend toward lowering teaching load may be accounted as another factor for

increasing demand for accounting faculty. Many business programs emphasizing research in their tenure and tenure

systems have reduced teaching load for faculty. For example, most teaching schools with moderate research

requirements have three-course teaching load per semester while research oriented schools have two or less per

semester for accounting faculty. The competition for new faculty makes teaching load an important determinant in

the mutual selection process between faculty candidates and schools. Therefore, in order to compete for good

candidates, some schools are willing to offer lower than normal teaching load to new faculty. As a result, schools

have to either increase class sizes or hire more faculty members to cover all courses offered.

Third, the increasing number of business programs seeking for accreditation from the AACSB also

contributes to the increasing demand for accounting faculty. To receive the AACSB accreditation, schools have to

meet standards that require programs to have a substantial faculty with terminal (doctoral) degree teaching in the

programs. In addition, the AACSB standards require faculty to have intellectual contributions (publications) to be

academically qualified. These standards force schools seeking for AACSB accreditation to hire more qualified

accounting faculty. Therefore, the demand for qualified accounting faculty has increased. According to AACSB, the

number of business schools achieving the AACSB accreditation has increased from 330 in November 2000 to 530 in

July 2006 (Sinning & Dykxhoorn, 2001; AACSB).5

Finally, the retirement of current faculty who are baby boomers deepens the plight of demand for

accounting faculty. Campbell, Hasselback, Hermanson, and Turner (1990) used the Hasselback faculty database and

used age 65 as retirement age to study whether there would be shortage of accounting faculty for a 25-year span

from 1990 to 2014. Their results showed a severe shortage trend of accounting faculty due to the reason that the

retirement rate is to be higher than the growth of replacement rate. In fact, many accounting programs now are

experiencing the pressure of losing faculty who are close to their retirement age.

SHORTAGE OF ACCOUNTING FACULTY: FROM THE SUPPLY PERSPECTIVE

Several reasons have contributed to the decline in accounting Ph.D. candidates. First, academia has not

been promoted as an accounting career choice. Carpenter and Robson (2004) claimed that a lack of interest in

academia might be the domain reason for low enrollment in accounting Ph.D. programs. According to their study,

the decline in Ph.D. program output first evident in 1995 has become a trend. Lack of interest in academia and fewer

applicants are severe factors in the decline of accounting Ph.D. candidates. Unaware of academia as an accounting

profession, negative perception of accounting academia, and upswing interests in other disciplines are other reasons

for fewer applicants in the Ph.D. programs.

Second, high opportunity costs can hinder potential candidates. On average, it takes students four to six

years beyond a masters degree to get a Ph.D. degree in accounting. The opportunity cost of current earnings and

future earnings to the candidates of pursuing a Ph.D. degree can be considerable. Most schools provide financial

aids to Ph.D. students on condition that they must be full-time students. Students thus have to give up their full-time

jobs to join the programs. However, many Ph.D. students perceived that the amount of financial aid is inadequate.6

5

6

Retrieved from its web site: http://www.aacsb.edu/General/InstLists.asp?lid=2.

Plumlee et al. (2006) found from the student survey that about one-third (one-fifth) of North American (international) students

48

Journal of College Teaching & Learning January 2008

Volume 5, Number 1

In addition, other highly desirable benefits such as health and life insurance are usually not available to Ph.D.

students. In order to attract more students to enter Ph.D. programs, universities and schools need to find ways to

reduce the opportunity costs imposed on students.

Third, the salary does not make the accounting academic career more attractive than the other disciplines.

For example, accounting has lost its monetary charm to the finance discipline in recent years. According to the

AACSB survey, the salaries of new hire of assistant accounting professor were $95,300 while the salaries of new

hire of assistant finance professor were $102,400 in 2003. Even though the salary gap between finance and

accounting professors narrowed down in 2005 and 2006, we probably will not see the result of increasing

accounting Ph.D. students until a few years later.

Fourth, tenure-track and research related pressure and high risk of not receiving tenure are perceived to

hinder students interest in accounting academia. Tenure represents job security, academia freedom, and a career

motivator. Although both teaching and research are important factors in the mission of schools, in reality, the

decisive factor in tenure and promotion decisions is research (Tang & Chamberlain, 2003). Many schools require

faculty to have both quality and quantity in their publications for tenure. On average, a new accounting Ph.D. has to

invest a minimum of 6 to 7 years to complete whatever work required in research, teaching and service before

he/she gets tenured (Stone, 1996). Research shows that most faculty do not receive tenure at their place of original

employment (Rittenburg, 1998). For a Ph.D. candidate, it is certain that more 10 years of life is at stake for her/him

to pursuit accounting academia as a career.

SUGGESTIONS TO INCREASE THE SUPPLY OF QUALIFIED PH.D. FACULTY

From the above discussions of shortage of accounting faculty from both the demand and supply

perspectives, we suggest that instead of curbing the increasing demand for accounting faculty, universities and

schools can take actions on increasing the supply of qualified Ph.D. faculty. We offer the following suggestions.

Promote Accounting Academia As One Of The Career Choices To Accounting Students

To increase the supply of qualified accounting faculty starts with attracting qualified candidates to

pursue Ph.D. degree in accounting. This will not solve the current shortage of accounting faculty since it will take at

least four to six years before we see an increase in supply. However, if we do not start promoting accounting

academia as a career choice now, the shortage of qualified accounting faculty will become even worse later on. In

addition to the suggestion by Plumlee et al. (2006) that AAA creates a website to provide information to attract

potential students seeking accounting Ph.D. degree, we suggest schools redesign courses offered to meet the

150-hour requirement to channel undergraduate and master students into accounting Ph.D. programs. Currently,

most schools have their curriculum designed to meet the 150-hour requirements for CPA examination, and they offer

courses that are practitioner-oriented for firms and organizations. We suggest that school include entry-level research

oriented courses in their 150-hour requirement plan to create a link between the accounting undergraduate/master

programs and the Ph.D. program.

Provide Adequate Financial Support To Ph.D. Students

Even without official statistics, our experience tells us that not all Ph.D. candidates are able to complete

their programs. When a student drops out of a program, it is not only the loss to the student but also a loss to the

university, which has put significant investment on the student. Among all of reasons for withdrawals, the common

two are financial problems and unsatisfactory academic performance. In many situations, financial problems lead to

unsatisfactory academic performance which results in withdrawals. In order to increase the supply of accounting

Ph.D. students, it is inevitable that universities have to provide adequate financial support to students. More

importantly, faculty members have to get involved in coursework and curriculum development to help Ph.D.

students succeed in the programs. The fellowships and scholarships not only can reduce the opportunity costs of

pursuing a Ph.D. degree but also can create better-trained doctoral candidates if the fellowships and scholarships

require Ph.D. students to be involved in doing research with faculty members.

see the financial support as inadequate.

49

Journal of College Teaching & Learning January 2008

Volume 5, Number 1

Motivate Current Faculty To Help Ph.D. Students Succeed In Program

The expense and cost of doctoral education are very expensive for both the schools and Ph.D. candidates.

To help new Ph.D. candidates succeed in the programs, faculty involvement with students is important. Traditionally,

universities place research more over teaching. Therefore, it locks up faculty to focus on doing research by

self-interest to get tenure and promotion. Since teaching doctoral courses is time-consuming and supervising a

dissertation takes extensive amount of time, faculty members may not feel that it is in their best interest to work with

Ph.D. students. The survey by Plumlee et al. (2006) reveals that almost half of the Ph.D. students feel that their

programs are too stressful. To release the students program-related stress and help them succeed in programs, we

suggest that universities provide incentives to create a mentoring atmosphere between faculty and Ph.D. students.

The incentives could include release course load, stipends and grants to faculty who are mentors to Ph.D. students.

Reevaluate The Tenure And Promotion System

Most programs have a tenure and promotion system in place for motivating faculty career development and

measuring faculty performance in teaching, research, and service. Although AACSB has favored mission-based

standards that tie publications to schools missions, many schools still have the tenure and promotion systems tied to

research more than teaching or service. Tension exists in most campuses regarding the relative importance of

teaching versus research in school missions and reward evaluations. It is time for the universities, deans and

department heads to review the tenure and promotion systems to have a balanced interaction of teaching, research

and service. Specific cultural changes and tenure and promotion policies are critical to facilitate facultys success in

academia and to accomplish the missions of university and department. In addition, we believe that a feasible tenure

and promotion system will improve the image of the accounting academia and attract more candidates to this

profession.

CONCLUSION

The continued quality of accounting education depends on the availability of qualified accounting faculty,

which in turn is the way to attract the best and the brightest students into accounting. Although the enrollments of

undergraduate and graduate students have turned into a positive sign, the quality of accounting education may be

threaten due to the result of shortage of qualified accounting faculty. The declining quality of accounting education

is evident in that many universities are coping with the shortage of faculty by hiring adjunct accounting faculty to

teach. It is time for universities to build a vision with leadership to reverse the trend of decreasing supply of

qualified accounting faculty.

Beginning with promoting accounting academia as a career choice to prospective Ph.D. students is a

starting point to reverse the unawareness and lack of interest in accounting Ph.D. programs. Schools can use the

150-hour degree programs to expose potential Ph.D. candidates to accounting Ph.D. programs by introducing

entry-level research oriented courses in the programs. Second, providing significant monetary fellowships and

scholarships not only reduces the opportunity cost but also creates better-trained doctoral candidates if the

fellowships and scholarship incorporate doctoral students research with facultys career development. Third, to help

Ph.D. students succeed in the programs, accounting faculty should be inspiring and passionate in serving as mentors

to students and working with them. Finally, implementing specific cultural changes and tenure and promotion

policies to create a supportive academic environment will help faculty career development and improve image of the

profession.

In conclusion, accounting education has recently been through the crisis of enrollment decline, and the

recent increase in enrollment does not make it totally out of the crisis yet. It is time for administrators and educators

to start thinking about how to increase the supply of qualified accounting faculty.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

103rd American Assembly, (2003). The future of the accounting profession. American Assembly Report.

Accounting Education Change Commission (AECC). (1990). Position statement No. One: Objectives of

education for accountants. Torrence, CA: Author.

50

Journal of College Teaching & Learning January 2008

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

Volume 5, Number 1

Accounting Education Change Commission (AECC). (1992). Position statement No. Two: The first course

in accounting. Torrence, CA: Author.

Albrecht, W. S. & Sack, R. J. (2000). Accounting education: Charting the course through a perilous future.

Accounting Education Series No.16. Sarasota, FL: American Accounting Association.

Ascierto, J. (2004). Opportunities abound for a career in accounting education. Retrieved from the web May

13, 2004. CalCPA Online, http://www.calcpa.org/community/careers/cc/articles/opportunities.html.

Campbell, T. L., Hasselback, J. R., Hermanson, R. H., & Turner D. H. (1990). Retirement demand and the

market of accounting doctorates. Issue in Accounting Education 5 (2), 219-221.

Carpenter, C. G., & Robson G.. S. (2004). Declining doctoral output in accounting. The CPA Journal, 74 (8),

68-69.

Friedlan, J. M. (1995). The effects of different teaching approaches on students perceptions of the skills

needed for success in accounting courses and by practicing accountants. Issues in accounting Education, 10

(1): 47-63.

Gullapalli, D. (2004). Crunch This! CPAs Become the New BMOCs. Wall Street Journal, July 27: C1 & C5.

Gullapalli, D. (2005). Take this job and file it; burdened by extra work created by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act,

CPAs leave the Big Four for better life. Wall Street Journal, May 4: C1.

Inman, B. C., Wenzler, A., & Wickert, P. D. (1989). Square pegs in round holes: Are accounting students

well-suited to todays accounting profession? Issues in Accounting Education, 4 (2), 29-47.

Plumlee, R. D., Kachelmeier, S. J., Madeo, S. A., Pratt, J. H., & Krull G. (2006). Assessing the shortage of

accounting faculty. Accounting Education, 21 (2), 113-126.

Read, W. J., Rama, D. V., & Raghunandan, K. (1998). Are publication requirements for accounting faculty

promotions still increasing? Issues in Accounting Education, 13 (2), 327-339.

Rittenberg, L. E. (1998). Hiring faculty: The best fit or best athlete. Issues in Accounting Education, 13

(3), 717-719.

Sinning, K. E., & Dykxhoorn, H. J. (2001). Processes implemented for AACSB accounting accreditation

and the degree of faculty involvement. Issues in Accounting Education, 16 (2), 181-204.

Stone, D. N. (1996). Getting tenure in accounting: A personal account of learning to dance with the

mountain. Issues in Accounting Education, 11 (1), 187-201.

Tiard, P. L., Braun R. L., & Meyer M. J. (2004). Accounting education: Response to corporate scandals.

Journal of Accountancy, 98 (5), 59-65.

Tang, T. L.P, & Chamberlain M. (2003). Effects of rank, tenure, length of service, and institution on faculty

attitude toward research and teaching: The case of regional state universities. Journal of Education for

Business, 79 (2), 103-110.

51

Journal of College Teaching & Learning January 2008

NOTES

52

Volume 5, Number 1

Você também pode gostar

- Problems Faced by Accounting AcademicsDocumento7 páginasProblems Faced by Accounting AcademicsDrahneel MarasiganAinda não há avaliações

- Prospect For Accounting Academics - Examining The Effect of Undergraduate Students' Career Decision.Documento37 páginasProspect For Accounting Academics - Examining The Effect of Undergraduate Students' Career Decision.Louierose Joy CopreAinda não há avaliações

- Vocational Skills Gap in UK Accounting EducationDocumento34 páginasVocational Skills Gap in UK Accounting EducationadillahAinda não há avaliações

- Accounting Education: A Review of the Changes That Have Occurred in the Last Five YearsNo EverandAccounting Education: A Review of the Changes That Have Occurred in the Last Five YearsAinda não há avaliações

- Perceptions Accounting Major and Minor Students of Inductory Accounting CourseDocumento10 páginasPerceptions Accounting Major and Minor Students of Inductory Accounting Coursenicoleginesantonio30Ainda não há avaliações

- Accounting Curriculum Redesign: Improving Cpa Exam Pass-Rates at A Small UniversityDocumento14 páginasAccounting Curriculum Redesign: Improving Cpa Exam Pass-Rates at A Small Universitygreen helpersAinda não há avaliações

- 56.students Perception Towards Majoring in Accounting (Ida Haryanti) PP 405-412Documento8 páginas56.students Perception Towards Majoring in Accounting (Ida Haryanti) PP 405-412upenapahangAinda não há avaliações

- Accountants Embracing Changing Times in AcademeDocumento12 páginasAccountants Embracing Changing Times in AcademeLorie Anne ValleAinda não há avaliações

- ShortageofaccountingphdsDocumento10 páginasShortageofaccountingphdsRizwan M KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Title I. Group 2. Availability of Accounting ProfessionalsDocumento3 páginasTitle I. Group 2. Availability of Accounting ProfessionalsSEBASTIAN, JENNY LAinda não há avaliações

- Paper For A e Final VersionDocumento34 páginasPaper For A e Final VersionPASCUAL, CYREL, TABANGINAinda não há avaliações

- Current Opinions On Forensic Accounting Education: Bonita KramerDocumento16 páginasCurrent Opinions On Forensic Accounting Education: Bonita Kramerray roseAinda não há avaliações

- GENERIC SKILLS KEY FOR NEW ACCOUNTANTSDocumento15 páginasGENERIC SKILLS KEY FOR NEW ACCOUNTANTSRahulSheoranAinda não há avaliações

- Related ReviewDocumento4 páginasRelated ReviewJune Kathleen VillanuevaAinda não há avaliações

- Cover SheetDocumento24 páginasCover SheetMarck SitoAinda não há avaliações

- Accounting Students' Attitude Towads AccountingDocumento29 páginasAccounting Students' Attitude Towads AccountingSham Salonga Pascual50% (2)

- Proposal Business Students Perception of Accounting and Its Determinants2Documento19 páginasProposal Business Students Perception of Accounting and Its Determinants2Edith MartinAinda não há avaliações

- Factors That Impact Attrition and Retention Rates For Accountancy Diploma Students: Evidence From AustraliaDocumento23 páginasFactors That Impact Attrition and Retention Rates For Accountancy Diploma Students: Evidence From AustraliaYvone Claire Fernandez SalmorinAinda não há avaliações

- G7 - Senior High School Learners' Perception of Accountancy As A Career PathDocumento38 páginasG7 - Senior High School Learners' Perception of Accountancy As A Career PathMyke Andrei OpilacAinda não há avaliações

- Becoming A CPA: Evidence From Recent Graduates Kimberly Charron D. Jordan LoweDocumento18 páginasBecoming A CPA: Evidence From Recent Graduates Kimberly Charron D. Jordan LoweJonathan BausingAinda não há avaliações

- Differences in views on accounting techniquesDocumento20 páginasDifferences in views on accounting techniquesEth Fikir NatAinda não há avaliações

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocumento10 páginasReview of Related Literature and StudiesJaira May BustardeAinda não há avaliações

- Future Proofing Tomorrows Accounting GraduatesDocumento18 páginasFuture Proofing Tomorrows Accounting GraduatesSanti Azmi MursalinaAinda não há avaliações

- 'Senior High School Learners' Perception of Accountancy As A Career PathDocumento41 páginas'Senior High School Learners' Perception of Accountancy As A Career PathMyke Andrei OpilacAinda não há avaliações

- 13 Problem-Based Learning (PBL) Does Accounting Education Need It JAEd 2012 Final SubmissionDocumento47 páginas13 Problem-Based Learning (PBL) Does Accounting Education Need It JAEd 2012 Final SubmissionMochamad Sandi NofiansyahAinda não há avaliações

- Bookkeeping RRLDocumento25 páginasBookkeeping RRLMark TepaceAinda não há avaliações

- Gmac Roi AnalysisDocumento12 páginasGmac Roi AnalysisdecnovAinda não há avaliações

- The Effect of Government Policy On Education in The UKDocumento10 páginasThe Effect of Government Policy On Education in The UKJane MansellAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis, Performance 2Documento25 páginasThesis, Performance 2Jezmelyn Antimano60% (5)

- Intern, Previously Used in The Medical Profession To Define A Person With A Degree ButDocumento2 páginasIntern, Previously Used in The Medical Profession To Define A Person With A Degree ButAnonymous 5sETvwAinda não há avaliações

- BibleDocumento15 páginasBiblevannesseAinda não há avaliações

- Inquiries Investigation and Immersion Group 5Documento8 páginasInquiries Investigation and Immersion Group 5Gerlen MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 PBDocumento11 páginas1 PBgiselleAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Associated with High Failure Rates in Accounting Courses: A Case Study of Omani StudentsDocumento14 páginasFactors Associated with High Failure Rates in Accounting Courses: A Case Study of Omani Studentsrichel sanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Accounting EducationDocumento16 páginasAccounting EducationcpacpacpaAinda não há avaliações

- Students' Perception of The Causes of Low Performance in Financial AccountingDocumento48 páginasStudents' Perception of The Causes of Low Performance in Financial AccountingJodie Sagdullas100% (2)

- Impacts of InternshipDocumento18 páginasImpacts of InternshipJonz AquinoAinda não há avaliações

- Manuscript ARTT 2020 PDFDocumento28 páginasManuscript ARTT 2020 PDFHenry James NepomucenoAinda não há avaliações

- PHINMA - Union College of Laguna A.Mabini ST., Sta. Cruz, Laguna, Santa Cruz, Philippines Bachelor of Science in AccountancyDocumento3 páginasPHINMA - Union College of Laguna A.Mabini ST., Sta. Cruz, Laguna, Santa Cruz, Philippines Bachelor of Science in AccountancyBryan TanAinda não há avaliações

- Awareness, Motivations and Readiness For Professional Accounting Education - A Case of Accounting Students in UiTM JohorDocumento10 páginasAwareness, Motivations and Readiness For Professional Accounting Education - A Case of Accounting Students in UiTM JohorfidelaluthfianaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter IDocumento8 páginasChapter ISeokjin KimAinda não há avaliações

- Academic Performance of Accountancy GradDocumento19 páginasAcademic Performance of Accountancy GradJeanette Agustin Gonzales-EikawaAinda não há avaliações

- ACCOUNTING INFORMATION AND EMPLOYMENT - AliDocumento9 páginasACCOUNTING INFORMATION AND EMPLOYMENT - AliAsadulla KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 2 - LiteratureDocumento21 páginasChapter 2 - LiteratureDianne Mei Tagabi CastroAinda não há avaliações

- Business & AdministrationDocumento2 páginasBusiness & AdministrationHehshjjjjsjAinda não há avaliações

- Do Students' Perceptions Matter? A Study of The Effect of Students' Perceptions On Academic PerformanceDocumento24 páginasDo Students' Perceptions Matter? A Study of The Effect of Students' Perceptions On Academic PerformanceIris DescentAinda não há avaliações

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocumento9 páginasThe Problem and Its BackgroundrpaldeonAinda não há avaliações

- 45.the Relationship Between Students' Perception and Intention (Anis Barieyah Mat Bahari) PP 327-332Documento6 páginas45.the Relationship Between Students' Perception and Intention (Anis Barieyah Mat Bahari) PP 327-332upenapahangAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Mohamed S. MDocumento8 páginas6 Mohamed S. MAshley MorganAinda não há avaliações

- Accounting Student Academic Dishonesty: What Accounting Faculty and Administrators Believe Douglas M. BoyleDocumento23 páginasAccounting Student Academic Dishonesty: What Accounting Faculty and Administrators Believe Douglas M. Boyle?????Ainda não há avaliações

- TTR Schoolstaffing 1Documento16 páginasTTR Schoolstaffing 1National Education Policy CenterAinda não há avaliações

- Causes of Students Failure in Financial Accounting in Senior Secondary Certificate Examination in Secondary Schools in Awka LgaDocumento73 páginasCauses of Students Failure in Financial Accounting in Senior Secondary Certificate Examination in Secondary Schools in Awka Lgajamessabraham2Ainda não há avaliações

- TTR Schoolstaffing 0Documento16 páginasTTR Schoolstaffing 0National Education Policy CenterAinda não há avaliações

- Student Academic PerformanceDocumento13 páginasStudent Academic PerformanceThalia SandersAinda não há avaliações

- Ref1.1 Accounting Learning in PhilippinesDocumento7 páginasRef1.1 Accounting Learning in PhilippinesRico Jay EmejasAinda não há avaliações

- abm students having hardtime Catching up with their Accounting SubjectsDocumento4 páginasabm students having hardtime Catching up with their Accounting SubjectsyhuijiexylieAinda não há avaliações

- Improving Written Skills in Accounting StudentsDocumento14 páginasImproving Written Skills in Accounting StudentsJay Pee EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- TTR SchoolstaffingDocumento16 páginasTTR SchoolstaffingNational Education Policy CenterAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Accountancy Students' Remote Learning During COVIDDocumento23 páginasFactors Affecting Accountancy Students' Remote Learning During COVIDedrianclydeAinda não há avaliações

- Time To Change Introductory AccountingDocumento5 páginasTime To Change Introductory AccountingthoritruongAinda não há avaliações

- (Ernst FDocumento2.031 páginas(Ernst Fitn_nti100% (1)

- Sap TablesDocumento29 páginasSap Tableslucaslu100% (14)

- Tire A PartDocumento13 páginasTire A Partitn_ntiAinda não há avaliações

- The Rules For Being Amazing PDFDocumento1 páginaThe Rules For Being Amazing PDFAkshay PrasathAinda não há avaliações

- Culture of FranceDocumento2 páginasCulture of Franceitn_ntiAinda não há avaliações

- Creation IndicatorDocumento2 páginasCreation Indicatoritn_ntiAinda não há avaliações

- Using MDM 7.1 Key-Mappings in A PI LandscapeDocumento40 páginasUsing MDM 7.1 Key-Mappings in A PI LandscapeshahrokhhassasianAinda não há avaliações

- Stock Transfer Configure DocumentDocumento7 páginasStock Transfer Configure DocumentSatyendra Gupta100% (1)

- Refrigerators, Best Refrigerators India, Compare Refrigerator BrandsDocumento3 páginasRefrigerators, Best Refrigerators India, Compare Refrigerator Brandsitn_ntiAinda não há avaliações

- SBI PO 17072011 AdvtDocumento3 páginasSBI PO 17072011 AdvtRupak NathAinda não há avaliações

- Work Immersion Career PreparationDocumento5 páginasWork Immersion Career PreparationAllysa Kim DumpAinda não há avaliações

- Essential criteria employee evaluationDocumento3 páginasEssential criteria employee evaluationMuhammad Hanis WafieyudinAinda não há avaliações

- Scope of WorkDocumento24 páginasScope of WorkGijo GeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- A Study On Employee Welfare Measures With Special Refference To Kitex LTD Kizhakkambalam Aluva 1384Documento7 páginasA Study On Employee Welfare Measures With Special Refference To Kitex LTD Kizhakkambalam Aluva 1384SULTANA TAJAinda não há avaliações

- Final Examinations Leadership and Management Name: - QUIJANO - Year/ Level: - Date/ TimeDocumento4 páginasFinal Examinations Leadership and Management Name: - QUIJANO - Year/ Level: - Date/ TimeARISAinda não há avaliações

- Succession Planning Practices and Their Impact On Employee RetentionDocumento80 páginasSuccession Planning Practices and Their Impact On Employee RetentionOUSMAN SEIDAinda não há avaliações

- IbmDocumento35 páginasIbmCyril ChettiarAinda não há avaliações

- NWPC vs Regional Tripartite Wages BoardDocumento2 páginasNWPC vs Regional Tripartite Wages BoardDeniece Loutchie A CorralAinda não há avaliações

- Institute For Construction Training and Development (ICTAD)Documento33 páginasInstitute For Construction Training and Development (ICTAD)Nuwan Sudharshana Weerathunga60% (5)

- Unit 2 d3Documento9 páginasUnit 2 d3api-359460355Ainda não há avaliações

- IJERT Critical Factors Influencing WorkDocumento3 páginasIJERT Critical Factors Influencing WorkAngelica MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- Cost Accounting Unit 2Documento75 páginasCost Accounting Unit 2lakshyajai70Ainda não há avaliações

- ED to Probe Flipkart, Bharti Walmart for FDI Norm ViolationsDocumento7 páginasED to Probe Flipkart, Bharti Walmart for FDI Norm ViolationsPrabhakar KumarAinda não há avaliações

- The Minimum Wages Act, 1948Documento40 páginasThe Minimum Wages Act, 1948Abha NagpalAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment FrameworkDocumento50 páginasAssessment FrameworkCharles OndiekiAinda não há avaliações

- Terminal ReportDocumento4 páginasTerminal ReportshamilleAinda não há avaliações

- Exports Impact On EconomyDocumento4 páginasExports Impact On EconomyjainchanchalAinda não há avaliações

- Reading and Writing Portfolio 3: Applying for a JobDocumento2 páginasReading and Writing Portfolio 3: Applying for a JobLeo AquinoAinda não há avaliações

- Nurses and Stress: Recognizing Causes and Seeking SolutionsDocumento10 páginasNurses and Stress: Recognizing Causes and Seeking SolutionsRAHMAT ALI PUTRAAinda não há avaliações

- Income Tax Law - A Capsule For Quick Recap IPCC Nov 18Documento28 páginasIncome Tax Law - A Capsule For Quick Recap IPCC Nov 18k moviesAinda não há avaliações

- Article 91. Right To Weekly Rest Day. It Shall Be The Duty of Every Employer, WhetherDocumento18 páginasArticle 91. Right To Weekly Rest Day. It Shall Be The Duty of Every Employer, WhetherApril Ann Sapinoso Bigay-PanghulanAinda não há avaliações

- Proposed Organisation Structure and Cost Projections for Tech SISDocumento5 páginasProposed Organisation Structure and Cost Projections for Tech SISSantosh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- HSHT Team Building Ice Breaker Manual 2008 09 PDFDocumento108 páginasHSHT Team Building Ice Breaker Manual 2008 09 PDFChris ChiangAinda não há avaliações

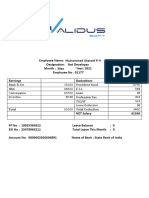

- Salary SlipDocumento4 páginasSalary Slipbindu mathaiAinda não há avaliações

- Decentralization Education PhilippinesDocumento34 páginasDecentralization Education PhilippinesDanvie Ryan Phi100% (4)

- TEF Business Management Training for African EntrepreneursDocumento21 páginasTEF Business Management Training for African EntrepreneursVictor EtudorAinda não há avaliações

- Annexure CD - 01': L T P/S SW/FW No. of Psda Total Credit UnitsDocumento4 páginasAnnexure CD - 01': L T P/S SW/FW No. of Psda Total Credit UnitsNitya SagarAinda não há avaliações

- Managing Culture at British Airways Hype, Hope and Reality PDFDocumento16 páginasManaging Culture at British Airways Hype, Hope and Reality PDF陆奕敏Ainda não há avaliações

- Washington SB 5599 (2023)Documento9 páginasWashington SB 5599 (2023)ThePoliticalHatAinda não há avaliações

- Quiz MB0038 Management Process and Organization Behaviour FinalDocumento63 páginasQuiz MB0038 Management Process and Organization Behaviour FinalSanehi RamAinda não há avaliações