Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Cash Flow PDF

Enviado por

Adhi SuryatnaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Cash Flow PDF

Enviado por

Adhi SuryatnaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

A test of the free cash flow and debt monitoring

hypotheses:

Evidence from audit pricing

Ferdinand A. Gul, Judy S. L. Tsui*

Department of Accountancy, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong

(Received June 1996; final version received January 1998)

Abstract

This study examines the association between free cash flow (FCF) and audit fees. The

association is expected given Jensens argument that managers of low growth/high FCF

firms engage in non-value-maximizing activities. These activities increase auditors assessments of inherent risk and, in turn, audit effort and fees. Jensen also argues debt

mitigates the non-value-maximizing activities. Thus, the positive FCF/audit fees association is expected to be weaker for low growth firms with high debt than for similar firms

with low debt. Regression results for a sample of low growth Hong Kong firms support

these hypotheses. ( 1998 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

JEL classification: L84; M40

Keywords: Free cash flow; Debt monitoring; Growth opportunities; Audit pricing

1. Introduction

A major strand of audit research focuses on the choice of auditors (Francis

and Wilson, 1988) and the determinants of audit fees (Simunic, 1980; Francis

and Simon, 1987; Craswell et al., 1995; Simunic and Stein, 1996). An underlying

hypothesis in these studies is that agency costs drive the demand for qualitydifferentiated audits in terms of the Big 6 vs. Non-Big 6 audit firms (previously

* Corresponding author. Tel.: (#852) 2788 7923; fax: (#852) 2788 7002; e-mail: acjt@

cityu.edu.hk.

0165-4101/98/$19.00 ( 1998 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

PII S 0 1 6 5 - 4 1 0 1 ( 9 8 ) 0 0 0 0 6 - 8

220

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

Big 8). Firms with higher agency costs are expected to hire higher quality,1 more

costly auditors in order to help mitigate agency costs. The demand for audit

services and for quality-differentiated auditing is seen to be the efficient resolution of costly contracting problems (Watts and Zimmerman, 1986).

Prior empirical evidence on the relation between agency cost variables and

the demand for audit quality is not strong (Palmrose, 1986; Simunic and Stein,

1987; Francis and Wilson, 1988; Defond, 1992). For example, prior studies using

agency cost proxies such as leverage and management ownership of shares have

not been very useful in explaining auditor choice. This could be due to leverage

and management ownership of shares serving as poor proxies for agency costs

or to the omission of other factors that cause cross-sectional variations in

agency costs and auditing demand. Recently, Craswell et al. (1995) point to

industry specialist auditors and argue that a combination of firm-specific and

industry-wide factors generate cross-sectional variations in the demand for

monitoring and in audit fees. The results of Craswell et al. are consistent with the

hypothesis that firms in certain industries demand higher quality audits provided by auditors with specialization in those industries and that this translates

into higher audit fees.

In this study, we explore a supply-side argument for the association between

agency costs and audit fees. More specifically, we examine the association

between free cash flow (FCF), identified by Jensen (1986) as a source of agency

problems for low growth firms, and audit fees. FCF is defined as the cash flow in

excess of that required to fund positive-net-present-value projects that is not

paid out in dividends. According to Jensen (1986, 1989), managers of low

growth/high FCF firms are involved in non-value-maximizing activities. We

expect managers of these firms to mask non-optimal expenditures by accounting

manipulation. We also expect auditors to respond to the higher probability of

accounting misstatements or irregularities by exerting greater audit effort and

charging higher audit fees. Jensen (1986, 1989) also argues that some low

growth/high FCF firms issue debt to mitigate the FCF agency problems. This

suggests the FCF/audit fees association depends on the debt level; auditors of

high FCF/high debt firms are likely to assess a lower risk of material misstatements, provide lower audit effort and charge lower audit fees than auditors of

high FCF/low debt firms.

To examine the relation between FCF and audit fees, data is collected for

publicly listed Hong Kong companies for 1993. Two multiple regression models

of audit fees are run for low growth firms audited by the Big 6, using two FCF

proxies suggested by Lang et al. (1991, p. 319). Each of the two models includes

1 Audit quality is defined as the joint probability of detecting and reporting material financial

statement errors (DeAngelo, 1981).

F.A. Gul, J.S.L Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

221

an interaction term for the FCF proxy and debt. Results indicate firms with high

FCF and low growth opportunities are associated with higher audit fees than

firms with low FCF and low growth opportunities. More importantly, the

interaction between FCF and debt is significant and in the predicted direction.

The negative interaction suggests at incrementally higher levels of debt, the

positive association between FCF and audit fees progressively decreases.

This paper contributes to auditing literature in several ways. First, it provides

evidence of an association between agency costs (proxied by FCF) and Big

6 audit fees not previously recognized in the literature. It is possible that FCF is

a better proxy for agency costs than other variables, such as management

ownership or leverage, previously examined by other researchers. Second, the

paper provides a supply-side explanation for the association between FCF and

audit fees. Third, unlike prior studies, debt has a significant impact on audit fees

but the direction and extent of the effect is dependent on the firms growth

opportunities and FCF. The results obtained here suggest prior studies that

examine debts role in audit pricing have an omitted variables problem when

they do not control for FCF and growth opportunities.

The next section of the paper provides a brief discussion of the theoretical

background of the study. This is then followed by sections on the research

method, results and discussion, and conclusion of the study.

2. Theoretical background

Jensen (1986, 1989) argues there is a conflict of interest between managers and

shareholders of firms with high FCF and low growth opportunities. Managers

of these firms act opportunistically and are involved in value destroying

activities and tend to overinvest and misuse the funds (Jensen, 1986, 1989).

Once managers have exhausted positive NPV projects, they proceed to invest in

negative NPV projects instead of paying dividends (Rubin, 1990; Lang et al.,

1991). Managers of these firms are expected to increase their compensation and

perquisites consumption at the expense of the shareholders, and engage in other

activities associated with management entrenchment (Shleifer and Vishny,

1989). Christie and Zimmerman (1994) suggest these non-value-maximizing

managers are more likely to mask non-optimal expenditures by accounting

manipulation.

Auditors design audits to reduce audit risk below a given level (see Lemon et

al., 1993). Audit risk is the likelihood of material errors in the clients financial

statements (Accounting Standards Board, Statement on Auditing Standards,

No. 47). It is the product of the likelihood that environmental factors, before

considering the quality of internal controls, will produce a material error

(inherent risk), the likelihood the internal controls system will not prevent or

detect a material error (control risk) and the likelihood the audit procedures

222

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

will fail to detect a material error not detected by the control system (detection

risk). The greater the inherent risk, ceteris paribus, the more resources the

auditor will have to devote to the audit to reduce detection risk to achieve

a given level of audit risk. Auditors are likely to assess firms with high FCF and

non-value-maximizing managers as having high levels of inherent risk. Hence,

ceteris paribus, they are likely to devote more resources to those firms audits

and charge those firms higher fees.

Issuance of debt without retention of the proceeds (i.e., higher leverage) is

likely to reduce agency costs associated with FCF. The required payments under

debt contracts reduce the cash flows management have available for non-valuemaximizing behavior and so restrict that behavior (Jensen, 1986, 1989; Stulz,

1990; Maloney et al., 1993). The debt market also provides management discipline (Rubin, 1990). These effects reduce inherent risk and in turn mitigate the

audit fees of high FCF firms. On the other hand, additional leverage can

motivate misstatements by management (e.g., to avoid accounting-based debt

covenant violations), so the net effect of higher leverage on inherent risk is

ambiguous. We expect, however, the former (cash discipline) effects to dominate

for high FCF/low growth firms.

To summarize, we argue that auditors charge higher fees in response to the

higher inherent risk associated with the non-value-maximizing activities of

managers of low growth firms with high FCF. Since debt can mitigate the

agency problems of FCF by requiring payments and providing a monitoring

mechanism through the debt market, it is likely that the relation between FCF

and audit fees depends on debt levels. This reasoning leads to the following

hypothesis:

Audit fees for low growth firms with high FCF and low levels of debt will be

higher than for similar firms with high FCF and high levels of debt, ceteris

paribus.

3. Research method

3.1. Data collection

We use data collected on Hong Kong publicly listed companies for 19932 from

Wardley Data Services Limited.3 A total of 449 firm observations are available.

2 The market and regulatory environments in Hong Kong are similar to those of the US and

Australia.

3 Wardley Data Services Limited is a securities company that maintains a database on all Hong

Kong publicly listed companies.

F.A. Gul, J.S.L Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

223

Data on auditor identity and audit fees are obtained from an inspection of

annual reports. After screening for low growth firms based on a composite

measure of growth, 46 firms audited by Big 6 audit firms are available for testing

the hypothesis. Table 1 presents a summary of the sample selection process.

Table 2 lists the number of companies for each industry group. No financial

institutions are included.4 Table 3 classifies the sample according to whether the

companies are audited by Big 6 or Non-Big 6 audit firms.

Table 1

Summary of the sample selection process

Sampling frame

Requirements

Firm observation for 1993 is available from Wardley Data Services Limited

Firm is incorporated in Hong Kong

Firm has shares that are publicly traded in Hong Kong

Number of firms qualifying"449

Screen for growth opportunitiesa

Requirements

Firm has non-missing values for three proxies of growth

(MKTBKEQ, MKTBKASS and PPE)

Number of sampling frame firms qualifying"418

Screen for low growth firmsb

Requirements

Firm has a composite factor score in the bottom quartile

Number of sampling frame firms qualifying"105

Screen for hypothesis subsample

Requirements

Firm has non-missing values for all the variables

Firm is audited by Big 6 audit firms

Number of firms qualifying for testing hypothesis"46

!Growth is the composite factor score obtained from common factor analysis using the following

three proxies: (i) MKTBKEQ"total market value of shares outstanding divided by total book

value of common equity; (ii) MKTBKASS"(total assets!total common equity#total value of

shares outstanding) divided by total assets; and (iii) PPE"gross plant, property and equipment

divided by market value of the firm.

"Low growth firms are those in the bottom quartile calculated on the basis of composite factor score

obtained from common factor analysis using MKTBKEQ, MKTBKASS and PPE.

4 Following the reasoning of Francis and Stokes (1986), financial institutions are excluded due to

their unique characteristics.

224

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

Table 2

Distribution of 1993 sample firms by industry

Total sample

Growth sampling

frame

Sampling frame

for hypothesis

11

84

157

172

15

10

11

82

143

159

15

8

0

17

17

7

4

1

449

418

46

Industry!

Utilities

Properties

Consolidated enterprises"

Industrials#

Hotels

Others

!Following Francis and Stokes (1986), data for financial institutions are dropped from the analysis.

" Consolidated enterprises include companies with principal activities in a combination of industry

groups such as retail, manufacturing and properties.

#Industrials include manufacturing or textile companies.

Table 3

Distribution of 1993 sample firms! audited by Big 6 and Non-Big 6 and by industry

Industry

Utilities

Properties

Consolidated enterprises

Industrials

Hotels

Others

Missing information

Total

Total sample

Hypothesis sample

Big 6

Non-Big 6

Big 6

10

52

119

134

13

6

334

0

334

1

29

26

23

2

3

84

31

115

0

17

17

7

4

1

46

0

46

449

46

!Following Francis and Stokes (1986), data for financial institutions are dropped from the analysis.

3.2. Research design

An OLS regression model is estimated to test the hypothesis. In this model, as

in prior studies, a number of control variables that are normally included in

audit fee models are used (Simunic, 1980; Francis, 1984; Craswell et al., 1995).

Auditee size is measured by the natural log of total assets (SIZE), while

long-term and short-term capital structure is represented by the debt to total

F.A. Gul, J.S.L Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

225

assets ratio (DE) and the quick ratio (QUICK) respectively. Asset mix is

measured by the ratio of current assets to total assets (CURRENT), and

organizational complexity is measured in terms of the number of directly owned

subsidiaries (SUB) and the percentage of subsidiaries incorporated outside

Hong Kong (FOREIGN). To control off-peak pricing of audit services, an

indicator variable (YE) is used (1 for non-December 31 year end and 0 otherwise). Finally, audit risk is measured in terms of the return on assets (ROA).

These variables have good explanatory power in the models (e.g., Craswell et al.,

1995) and are robust across different samples, time periods and countries. In

order to control for possible client industry effects, indicator variables for

different industries are also included. The hypothesis is tested by including an

interaction term for FCF and debt in the model.

3.3. Variable measurement

The experimental variables of interest are FCF and FCF/debt interaction,

and the dependent variable is the natural log of total audit fees. Since the

hypothesis is tested with low growth firms, a composite growth opportunities

factor score is calculated and used to identify these firms.

3.3.1. Growth opportunities

There is no consensus on the most reliable proxy for growth. Three widely

used proxies are employed in this study (Chung and Charoenwong, 1991; Gaver

and Gaver, 1993; Skinner, 1993). Factor analysis is conducted on the three

proxies to arrive at a composite factor score (see Gaver and Gaver (1993) for an

example of this procedure).

The three proxies are:

1. The ratio of the market value of equity to the book value of equity

(MKTBKEQ)

This proxy is used because the difference between the market value and the

book value of equity incorporates the value of the firms future investment

opportunities. The higher the ratio, the greater the value of growth opportunities.

2. The ratio of the market value of assets to the book value of assets

(MKTBKASS)

The higher the ratio, the lower the ratio of assets-in-place to the firm value

and the greater the value of growth opportunities.

3. The ratio of gross plant, property and equipment to the market value of the

firm (PPE)

Skinner (1993) suggests that past investments in gross plant, property and

equipment can also characterize assets-in-place. The higher the ratio, the

higher the assets-in-place and the lower the growth opportunities.

226

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

3.3.2. Common factor analysis for growth

The results of the factor analysis are presented in Table 4.

Due to missing values of either one or more of the growth proxies from the

sampling frame of 449 firm observations, only 418 are included for factor

analysis. Panel A shows the estimated communalities for each of the three

growth measures.5 Panel B presents the eigenvalues of the reduced correlation

matrix of the three growth measures, and Panel C presents the correlations

between the common factor and the three measures of growth. The common

factor with an eigenvalue of 1.658 is significantly positively correlated with

MKTBKEQ and MKTBKASS and negatively correlated with PPE.6

3.3.3. Free cash flow

Unfortunately, as pointed out by Lang et al. (1991), the literature provides

little or no guidance on the measures for FCF as defined by Jensen (1986). To

Table 4

Statistics related to common factor analysis of three measures of growth opportunities for 418 firms

for 1993

Panel A: Estimated communalities of three growth measures!

MKTBKEQ

MKTBKASS

0.748

0.740

PPE

0.061

Panel B: Eigenvalues of the reduced correlation matrix of three growth measures

MKTBKEQ"

MKTBKASS

PPE

1.658

0.022

!0.130

Panel C: Correlations between the common factor and three growth measures

MKTBKEQ

MKTBKASS

PPE

0.970***

0.957***

!0.251***

***"p(0.001.

!Growth is the composite factor score obtained from common factor analysis using the following

three proxies: (i) MKTBKEQ"total market value of shares outstanding divided by total book

value of common equity; (ii) MKTBKASS"(total assets!total common equity#total value of

shares outstanding) divided by total assets; and (iii) PPE"gross plant, property and equipment

divided by market value of the firm.

" Harman (1976) and Cattrell (1966) suggest that if the first eigenvalue alone exceeds the sum of the

three communalities, this one common factor explains the intercorrelations among the individual

measures.

5 Communalities are squared multiple correlations obtained from regressing each of the growth

proxies on the other three measures.

6 Since the estimated communality for PPE is rather low, we also classify low growth firms on the

basis of the individual measures, i.e. MKTBKEQ and MKTBKASS, which have been used

extensively as proxies for growth (Smith and Watts, 1992; Gaver and Gaver, 1993), and run separate

regressions for each proxy to determine if the results are different.

F.A. Gul, J.S.L Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

227

date, several proxies have appeared in finance literature and we adopt two of the

most widely used free cash flow definitions, those used by Lehn and Poulsen

(1989) and Lang et al. (1991). Lehn and Poulsen (1989) define FCF as the

operating income before depreciation minus taxes, interest expenses, preferred

dividends, and ordinary dividends. Such free cash flow definition is normalized

by either the total book value of equity or total assets in the previous year. It

should be noted that these measures of FCF by themselves do not provide

a measure of the availability of positive NPV projects. However, in combination

with low growth, they suggest the existence of cash flow in excess of that

required to fund positive NPV projects.

The two measures of free cash flow used are defined as follows:

FCFBEQ"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BEQ,

FCFBA"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BA,

where, INC is the operating income before depreciation; TAX is the total taxes;

INTEXP is the gross interest expenses on short- and long-term debt; PREDIV

is the total dividend on preferred shares; ORDIV is the total dividend on

ordinary shares; BEQ is the total book value of equity in previous year and BA

is the total assets in previous year.

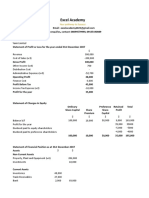

3.4. Descriptive statistics

Table 5 presents descriptive statistics for the experimental, control and dependent variables in this study. The total audit fees and total assets in millions of

Hong Kong dollars are also given in Table 5 (see page 228).

3.5. Model specification

To test the hypothesis, firms with bottom quartile of growth factor scores are

analyzed using the following OLS regression model:

LAF"b #b SIZE#b DE#b CURRENT#b QUICK

0

1

2

3

4

#b YE#b SUB#b FOREIGN#b ROA

5

6

7

8

#b PROP#b CONSOL#b INDUS

9

10

11

#b HOTEL#b FCF#b FCF*DE

12

13

14

where LAF is the natural log of total audit fees.

Control variables

SIZE

DE

" natural log of total assets

" book value of long-term debt divided by total assets

228

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

Table 5

Descriptive statistics of all variables for 1993 sample used to test the hypothesis (N"46)

Variable

Mean

Std Dev

LAF

AF (HK$M)

SIZE

TA (HK$M)

DE

CURRENT

QUICK

YE"1

SUB

FOREIGN

ROA

FCFBEQ

FCFBA

GROWTH

MKTBKEQ

MKTBKASS

PPE

0.389

2.005

7.934

6754

0.135

0.366

1.380

71.7%

5.901

0.408

15.79

0.257

0.116

!0.710

0.615

0.664

1.784

0.716

2.370

1.338

11412

0.113

0.218

1.055

2.113

0.216

18.60

0.576

0.165

0.118

0.166

0.281

1.540

Range

!0.949

0.387

4.718

112

0.00008

0.066

0.150

2.646

0.039

2.217

!0.012

!0.010

!1.111

0.146

!0.897

0.055

2.766

15.900

10.990

59475

0.515

0.914

5.500

11.958

0.840

100

2.744

0.756

!0.547

0.866

0.963

8.170

LAF"natural log of total audit fees

AF"total audit fees (HK$M)

SIZE"natural log of total assets

TA"total assets (HK$M)

DE"book value of long-term debt divided by total assets

CURRENT"ratio of current assets to total assets

QUICK"ratio of current assets less inventory to current liabilities

YE"dummy variable, 0"31/12 fiscal year end, 1"non-31/12 fiscal year end

SUB"square root of number of directly owned subsidiaries

FOREIGN"percentage of subsidiaries incorporated in countries other than Hong Kong

ROA"profit before interest and tax divided by total assets

FCFBEQ"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BEQ

FCFBA"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BA

where,

INC"operating income before depreciation

TAX"total taxes

INTEXP"gross interest expenses on short- and long-term debt

PREDIV"total dividend on preferred shares

ORDIV"total dividend on ordinary shares

BEQ"total book value of equity in previous year

BA"total assets in previous year

GROWTH"composite factor score obtained from common factor analysis using the following

three proxies;

MKTBKEQ"total market value of shares outstanding divided by total book value of common

equity

MKTBKASS"(total assets!total common equity#total value of shares outstanding) divided

by total assets

PPE"gross plant, property and equipment divided by market value of the firm.

F.A. Gul, J.S.L Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

229

CURRENT " ratio of current assets to total assets

QUICK

" ratio of current assets less inventory to current liabilities

YE

" dummy variable, 0"31/12 fiscal year end, 1"non-31/12

fiscal year end

SUB

" square root of number of directly owned subsidiaries

FOREIGN " percentage of subsidiaries incorporated in countries other than

Hong Kong

ROA

" profit before interest and tax divided by total assets

PROP

" dummy variable, 1"properties, 0"others

CONSOL " dummy variable, 1"consolidated enterprises, 0"others

INDUS

" dummy variable, 1"industrials, 0"others

HOTEL

" dummy variable, 1"hotels, 0"others

Experimenqtal variables

FCF is the two measures of free cash flow.

FCFBEQ"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BEQ,

FCFBA"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BA,

where, INC is the operating income before depreciation; TAX is the total taxes;

INTEXP is the gross interest expenses on short- and long-term debt; PREDIV

is the total dividend on preferred shares; ORDIV is the total dividend on

ordinary shares; BEQ is the total book value of equity in previous year; BA is

the total assets in previous year.

FCF*DE is the interaction between FCF and DE.

Indicator variables for industries are introduced to control for inter-industry

effects.7A significant interaction term (FCF*DE) is interpreted to mean that the

effect of FCF on the dependent variable depends on debt. A negative interaction

coefficient is predicted since the positive association between FCF and audit fees

is expected to decrease at higher levels of debt. As a control sample, a similar

regression is run for the high growth subsample (N"46)8 selected on the basis

of the top quartile of growth factor scores.

4. Results and discussion

The results reported in Panel A of Table 6 show the association between FCF

and audit fees is positive, significant, and in the predicted direction using either

7 Due to the small sample size, it is not possible to restrict the study to a single industry to

eliminate possible inter-industry effects.

8 After deleting for missing observations from the top quartile subsample (N"105), there are 46

firms audited by Big 6 and 10 audited by Non-Big 6 audit firms.

230

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

Table 6

Regression results for low growth (bottom quartile) firms for 1993 (N"46) (figures in parentheses

represent t-values)

Variables

Predicted

sign

Panel A: Full model with industry control

INTERCEPT

Control variables

SIZE

DE

CURRENT

QUICK

YE

SUB

FOREIGN

ROA

PROP

CONSOL

INDUS

HOTEL

Experimental variables

FCFBEQ

FCFBEQ*DE

FCFBA

FCFBA*DE

F value

R2

*p(0.10

**p(0.05

Model 1

Model 2

!4.347***

(!5.909)

!4.425***

(!6.181)

0.477***

(6.519)

0.413

(0.703)

1.113***

(2.535)

0.028

(0.364)

!0.038

(!0.226)

0.092**

(2.025)

!0.445*

(!1.320)

!0.003

(!0.687)

!0.024

(!0.054)

0.326

(0.761)

0.211

(0.457)

0.097

(0.199)

0.478***

(6.780)

0.641

(1.083)

1.156***

(2.700)

0.098

(1.108)

!0.088

(!0.534)

0.095**

(2.171)

!0.492

(!1.504)

!0.003

(!0.561)

0.027

(0.062)

0.340

(0.818)

0.187

(0.421)

0.071

(0.150)

1.071***

(2.739)

!8.469***

(!2.614)

8.412***

79.16%

***p(0.01

2.691**

(2.406)

!24.012***

(!3.144)

9.101***

80.43%

232

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

Table 6 (continued)

FCFBEQ"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BEQ

FCFBA"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BA

where,

INC"operating income before depreciation

TAX"total taxes

INTEXP"gross interest expenses on short- and long-term debt

PREDIV"total dividend on preferred shares

ORDIV"total dividend on ordinary shares

BEQ"total book value of equity in previous year

BA"total assets in previous year

FCFBEQ*DE"interaction between FCFBEQ and DE

FCFBA*DE"interaction between FCFBA and DE.

of the two FCF variables. The interaction terms comprising the first order

interaction between FCFBEQ and debt and FCFBA and debt, respectively, are

also significant and in the predicted direction. Some of the control variables are

significant and consistent with prior studies (e.g., Craswell et al., 1995). For

example, the ratios of current assets to total assets are both significant and in the

correct direction. Similar significant results are also obtained for the variables

SIZE and SUB. Except for the variables FOREIGN and QUICK, the other

control variables are all in the expected direction, but insignificant.

Panel B of Table 6 reports the results for a reduced model without the control

variables for industries, QUICK, YE, FOREIGN and ROA, and the results for

the experimental variables are similar.9 As an additional check on the use of the

growth proxy, two identical regressions are run for low growth firms, each

classified on the basis of the bottom quartile of individual growth measures

MKTBKEQ and MKTBKASS respectively.10 The results show both the main

effects of FCF and the interactions between debt and FCF are significant

(p(0.01) and also in the predicted direction. The significance levels of the other

variables are qualitatively similar to the results reported in Panel A of Table 6.

The regression results for the high growth subsample firms classified on the

basis of growth factor scores are reported in Table 7. As expected, none of the

interactions nor the main effects of FCF are significant.

9 These control variables are not significant in the regression of the full model as shown in Panel

A of Table 6.

10 These additional analyses are prompted by a query raised by the referee regarding the low

estimated communality for the PPE measure. The results show that the partition of the sample into

high and low growth opportunities is not sensitive to the exclusion of this growth proxy in the

common factor.

F.A. Gul, J.S.L Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

233

Table 7

Regression results for high growth (top quartile) firms for 1993 (N"46) (figures in parentheses

represent t-values)

Variables

Predicted

Sign

INTERCEPT

Control variables

SIZE

DE

CURRENT

QUICK

YE

SUB

FOREIGN

ROA

PROP

CONSOL

INDUS

HOTEL

Experimental variables

FCFBEQ

FCFBEQ*DE

FCFBA

FCFBA*DE

F value

R2

*p(0.10

**p(0.05

Model 1

Model 2

!1.920

(!1.680)

!2.408**

(!2.588)

0.248**

(2.220)

0.429

(0.927)

!1.248*

(!1.676)

!0.046

(!0.639)

!0.075

(!0.356)

0.098*

(1.636)

0.154

(0.281)

0.001

(0.074)

1.129*

(1.843)

0.653

(1.331)

0.531

(0.989)

0.424

(0.534)

0.287***

(2.884)

0.363

(0.696)

!0.602

(!0.948)

!0.025

(!0.341)

0.069

(0.330)

0.090*

(1.525)

0.247

(0.464)

0.015

(1.199)

0.603

(1.144)

0.302

(0.710)

0.056

(0.117)

0.258

(0.341)

0.127

(0.683)

!5.233

(!1.606)

3.781***

63.07%

***p(0.01

!1.052

(!1.290)

!7.534

(!1.025)

4.008***

64.42%

234

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

Table 7 (continued)

The above asterisks indicate significance levels in a one-tail or two-tail t-test (as appropriate).

SIZE"natural log of total assets

DE"book value of long-term debt divided by total assets

CURRENT"ratio of current assets to total assets

QUICK"ratio of current assets less inventory to current liabilities

YE"dummy variable, 0"31/12 fiscal year end, 1"non-31/12 fiscal year end

SUB"square root of number of directly owned subsidiaries

FOREIGN"percentage of subsidiaries incorporated in countries other than Hong Kong

ROA"profit before interest and tax divided by total assets

PROP"dummy variable, 1"properties, 0"others

CONSOL"dummy variable, 1"consolidated enterprises, 0"others

INDUS"dummy variable, 1"industrials, 0"others

HOTEL"dummy variable, 1"hotels, 0"others

FCFBEQ"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BEQ

FCFBA"(INC!TAX!INTEXP!PREDIV!ORDIV)/BA

where,

INC"operating income before depreciation

TAX"total taxes

INTEXP"gross interest expenses on short- and long-term debt

PREDIV"total dividend on preferred shares

ORDIV"total dividend on ordinary shares

BEQ"total book value of equity in previous year

BA"total assets in previous year

FCFBEQ*DE"interaction between FCFBEQ and DE

FCFBA*DE"interaction between FCFBA and DE

The positive coefficients for FCF in the models in both Panels A and B of

Table 6 suggest FCF is positively related to fees. The interaction parameter

reflects the extent to which fees are affected by FCF and debt. A differentiation

of the equation with respect to FCF provides b -b (Debt). This implies that

13 14

the positive relationship between FCF and audit fees progressively reduces at

higher levels of debt.11 The results are consistent with the argument that, ceteris

paribus, auditors supply12 more audit effort and charge higher audit fees in

11 Further analyses are performed to compare the mean scores of audit fees for the low and high

FCF groups with high and low debt. As expected, mean audit fees are higher for firms with high FCF

and low debt than firms with high FCF and high debt (results not reported here are available from

the authors).

12 The supply-side argument suggests that similar regression results should also be obtained for

Non-Big 6 auditees. Unfortunately, the small sample size (N"20) precludes such an analysis.

However, a full regression with all the variables including an indicator variable for Big 6 (N"46)

and Non-Big 6 (N"20) auditees yielded similar significant results for FCF and the interaction

between FCF and debt (results available from the authors).

F.A. Gul, J.S.L Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

235

response to the higher inherent risk associated with higher levels of FCF

(combined with low growth opportunities). They are also consistent with auditors of high FCF/high debt firms assessing lower levels of inherent risk and,

therefore, supplying lower levels of audit effort (and lower audit fees) than

auditors of high FCF/low debt firms.

5. Conclusion

This study investigates the effect of FCF and debt on audit fees. The results

show the association between FCF and audit fees is dependent on debt. The

significant and positive main effects of FCF and the negative sign of the

interaction terms suggest that at progressively higher levels of debt, the positive

association between FCF and audit fees decreases.

Our test, however, does not unambiguously preclude other explanations

such as the demand for higher quality audits to mitigate the agency costs

of FCF. Another possibility is that auditors charge higher fees since they are

aware that firms have the ability to pay more because of the availability of

discretionary resources as a result of high FCF and low growth opportunities. It

is also possible that firms with high FCF and low debt have entrenched

management (Shleifer and Vishny, 1989). The higher fees could represent high

perquisites such as cross-subsidization of other dealings managers have with the

auditors.13 The higher fees could also reflect a premium for higher risk of

litigation (Simunic and Stein, 1996). The above possibilities suggest room for

further research.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge comments from Dan Simunic (the referee), Ross Watts

(the editor), Jere Francis, Theodore Mock, Eric Noreen, Greg Whittred,

the participants at the University of California, Berkeley, the Hong Kong

University of Science and Technology and University of Otago workshops,

the 1996 Hong Kong Academic Conference and AAANZ Conference. We

also acknowledge the financial assistance provided by a Hong Kong RGC

grant.

13 These could be in the form of manager-specific implicit contracts (see Shleifer and Vishny, 1989,

p.132).

236

F.A. Gul, J.S.L. Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

References

Cattrell, R.B., 1966. The screen test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research 1,

245276.

Christie, A.A., Zimmerman, J., 1994. Efficient and opportunistic choices of accounting procedures:

corporate control contests. The Accounting Review 69 (4), 539566.

Chung, K., Charoenwong, C., 1991. Investment options, assets-in-place, and the risk of stocks.

Financial Management 20, 2133.

Craswell, A., Francis, J., Taylor, S., 1995. Auditor brand name reputations and industry specializations. Journal of Accounting and Economics 20, 297322.

DeAngelo, L.E., 1981. Auditor size and auditor quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics,

183199.

Defond, M.L., 1992. The association between changes in client firm agency costs and auditor

switching. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 11, 1631.

Francis, J., 1984. The effect of audit firm size on audit prices: a study of the Australian market.

Journal of Accounting and Economics 6, 133151.

Francis, J., Simon, D., 1987. A test of audit pricing in the small-client segment of the U.S. audit

market. The Accounting Review 62, 145157.

Francis, J., Stokes, D., 1986. Audit prices, product differentiation and scale economies: further

evidence from the Australian audit market. Journal of Accounting Research 24, 383393.

Francis, J., Wilson, E., 1988. Auditor changes: a joint test of theories relating to agency costs and

auditor differentiation. The Accounting Review 63, 663682.

Gaver, J.J., Gaver, K.M., 1993. Additional evidence on the association between the investment

opportunity set and corporate financing, dividend and compensation policies. Journal of Accounting and Economics 16, 125160.

Harman, H.H., 1976. Modern Factor Analysis. 3rd ed., University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Jensen, M.C., 1986. Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. American

Economic Review 76, 323329.

Jensen, M.C., 1989. Eclipse of the public corporation. Harvard Business Review 5, 6174.

Lang, L.H.P., Stulz, R.M., Walkling, R.A., 1991. A test of the free cash flow hypothesis, the case of

bidder returns. Journal of Financial Economics 29, 315335.

Lehn, K., Poulsen, A., 1989. Free cash flow and stockholder gains in going private transactions.

Journal of Finance 44, 771787.

Lemon, W.M., Arens, A.A., Loebbecke, J.K., 1993. Auditing: an Integrated Approach. Prentice-Hall,

Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Maloney, M.T., McCormick, R.E., Mitchell, M.L., 1993. Managerial decision making and capital

structure. Journal of Business 66, 189217.

Palmrose, Z., 1986. Audit fees and auditor size:: further evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 24,

97110.

Rubin, P.H., 1990. Managing Business Transactions. The Free Press, New York.

Shleifer, A., Vishny, R.W., 1989. Management entrenchment, the case of manager-specific investments. Journal of Financial Economics 25, 123139.

Simunic, D.A., 1980. The pricing of audit services: theory and evidence. Journal of Accounting

Research 18, 161190.

Simunic, D.A., Stein, M.T., 1987. Product differentiation in auditing: auditor choice in the market for

unseasoned new issues. Canadian Certified General Accountants Research Foundation, Vancouver.

Simunic, D.A., Stein, M.T., 1996. The impact of litigation risk on audit pricing: a review of the

economics and the evidence. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 15, 119134.

Skinner, D., 1993. The investment opportunity set and accounting procedure choice: preliminary

evidence. Journal of Accounting and Economics 16, 407445.

F.A. Gul, J.S.L Tsui / Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1998) 219237

237

Smith, C.W. Jr., Watts, R.L., 1992. The investment opportunity set and corporate financing,

dividend and compensation policies. Journal of Financial Economics 32, 263292.

Stulz, R.M., 1990. Managerial discretion and optimal financing policies. Journal of Financial

Economics 26, 327.

Watts, R.L., Zimmerman, J.L., 1986. Positive Accounting Theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs,

NJ.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Test Bank For Advanced Accounting 2nd Edition by HamlenDocumento40 páginasTest Bank For Advanced Accounting 2nd Edition by HamlenAngelique Kate Tanding Duguiang100% (1)

- Horngren Ima16 Tif 15 GEDocumento49 páginasHorngren Ima16 Tif 15 GEasem shaban100% (1)

- ACC3201Documento7 páginasACC3201natlyhAinda não há avaliações

- Principles of Managerial Finance: Fifteenth Edition, Global EditionDocumento22 páginasPrinciples of Managerial Finance: Fifteenth Edition, Global Editionpatrecia 18960% (1)

- Money TimesDocumento20 páginasMoney TimespasamvAinda não há avaliações

- TDS On SalariesDocumento3 páginasTDS On SalariesSpUnky RohitAinda não há avaliações

- 23 MergersDocumento44 páginas23 MergerssiaapaAinda não há avaliações

- 2019 1099-Consol Morgan Stanley 5948 KentDocumento10 páginas2019 1099-Consol Morgan Stanley 5948 Kentesteysi775Ainda não há avaliações

- Eceecon Problem Set 2Documento8 páginasEceecon Problem Set 2Jervin JamillaAinda não há avaliações

- Verizon Financial Analysis Draft (Finall)Documento22 páginasVerizon Financial Analysis Draft (Finall)MadfloridaAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation On InvestmentDocumento155 páginasPresentation On InvestmentIkmal AhmadAinda não há avaliações

- Hospitality Financial Management Ch.4 Feasibility StudyDocumento15 páginasHospitality Financial Management Ch.4 Feasibility StudyMuhammad Salihin JaafarAinda não há avaliações

- Regulation MyNotesDocumento50 páginasRegulation MyNotesaudalogy100% (1)

- Delegation of Authority: Duluxgroup LimitedDocumento7 páginasDelegation of Authority: Duluxgroup LimitedGaurav WadhwaAinda não há avaliações

- FA II - Chapter 1, Current LiabilitiesDocumento94 páginasFA II - Chapter 1, Current LiabilitiesBeamlak WegayehuAinda não há avaliações

- RAM A Study On Equity Research Analysis at India Bulls LimitedDocumento44 páginasRAM A Study On Equity Research Analysis at India Bulls Limitedalapati173768Ainda não há avaliações

- Canara Bank Annual Report 2010 11Documento217 páginasCanara Bank Annual Report 2010 11Sagar KedarAinda não há avaliações

- Micro Review Exam 2 1Documento17 páginasMicro Review Exam 2 1Death Surgeon MEME MASTERAinda não há avaliações

- INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT Mod.Documento142 páginasINVESTMENT MANAGEMENT Mod.Terefe DubeAinda não há avaliações

- ZSE Presentation On REITsDocumento28 páginasZSE Presentation On REITsNelson MrewaAinda não há avaliações

- Written WorkDocumento3 páginasWritten WorkKenjie SobrevegaAinda não há avaliações

- Share Certificate and Share WarrantDocumento4 páginasShare Certificate and Share WarrantHemalatha DwadasiAinda não há avaliações

- Practice Problems1Documento15 páginasPractice Problems1Divyam GargAinda não há avaliações

- Illustration 1 & 2Documento5 páginasIllustration 1 & 2faith olaAinda não há avaliações

- 12 2019 AIF March 11 FINALDocumento72 páginas12 2019 AIF March 11 FINALSugar RayAinda não há avaliações

- Audit of Equity InvestmentsDocumento5 páginasAudit of Equity Investmentsdummy accountAinda não há avaliações

- Viii - Audit of Equity PROBLEM NO. 1 - Equity Components SolutionDocumento22 páginasViii - Audit of Equity PROBLEM NO. 1 - Equity Components SolutionKirstine DelegenciaAinda não há avaliações

- Liberty Mills Limited: Audit ReportDocumento41 páginasLiberty Mills Limited: Audit ReportAmad MughalAinda não há avaliações

- HRM 543 ReportDocumento27 páginasHRM 543 Reportimran shihabAinda não há avaliações

- 2022 3Q ReportDocumento70 páginas2022 3Q ReportN.a. M. TandayagAinda não há avaliações