Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Right To Speedy Disposition of Cases

Enviado por

Dei GonzagaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Right To Speedy Disposition of Cases

Enviado por

Dei GonzagaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Research on Speedy Disposition

SPEEDY DISPOSITION:

A Constitutionally Guaranteed Right

According to the Supreme Court in

Coscolluela v. Sanbiganbayan (First

Division) and People of the Philippines1:

Speedy disposition, broader concept than

the speedy trial.

The right to a speedy disposition of cases

encompasses the broader purview of the

entire proceedings of which trial proper is

but a stage. As held in Dansal v. Fernandez,

Sr.:4

A persons right to the speedy disposition of

his case is guaranteed under Section 16,

Article III of the 1987 Constitution, which

provides:

Initially embodied in Section 16, Article IV

of the 1973 Constitution, the constitutional

provision o[on speedy disposition of cases]

is one of three provisions mandating

speedier dispensation of justice. 5 It

guarantees the right of all persons to a

speedy disposition of their case; includes

within its contemplation the periods

before, during and after trial, and affords

broader protection than Section 14(2),6

which guarantees just the right to a

speedy trial. It is more embracing than the

protection under Article VII, Section 15,

which covers only the period after the

submission of the case. 7

The present

constitutional provision applies to civil,

criminal

and

administrative

cases. 8

(emphasis and underscoring supplied;

citations in original)

SEC. 16. All persons shall have

the right to a speedy disposition of

their cases before all judicial,

quasi-judicial, or administrative

bodies.

This constitutional right is not limited to the

accused in criminal proceedings but extends

to all parties in all cases, be it civil or

administrative in nature, as well as all

proceedings, either judicial or quasi-judicial.

In this accord, any party to a case may

demand expeditious action to all officials

who are tasked with the administration of

justice.2

Speedy Disposition: Not a Mathematical

Concept

The right to speedy disposition of cases

should be understood to be a relative or

flexible concept such that a mere

mathematical reckoning of the time involved

would not be sufficient.3

It is, in criminal cases however where

the need to a speedy disposition of their

cases is more pronounced. It is so,

because in criminal cases, it is not only

the honor and reputation but even the

4

5

6

Rafael L. Coscolluela v. Sanbiganbayan (First

Division) and People of the Philippines, G.R. No.

191411, 15 July 2013.

Citing Roquero v. Chancellor of UP-Manila, G.R. No.

181851, 09 March 2010 (614 SCRA 723, 732);

citations omitted.

Coscolluela, citing Enriquez v. Office of the

Ombudsman, G.R. Nos. 174902-06, 15 February 2008

(545 SCRA 618, 626).

7

8

G.R. No. 126814, 02 March 2000 (383 Phil. 897, 905).

Bernas, The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the

Philippines: A Commentary, 1996, p. 489.

Art. III, Sec 14 (2). " In all criminal prosecutions, the

accused shall be presumed innocent until the contrary

is proved, and shall enjoy the right to be heard by

himself and counsel, to be informed of the nature and

cause of the accusation against him, to have a

speedy, impartial, and public trial, to meet the

witnesses face to face, and to have compulsory

process to secure the attendance of witnesses and the

production of evidence in his behalf. However, after

arraignment, trial may proceed notwithstanding the

absence of the accused provided that he has been

duly notified and his failure to appear is unjustifiable.

(underscoring supplied)

Bernas, id., citing Talabon vs. Iloilo Provincial Warden,

78 Phil 599.

Bernas, id.

liberty of the accused (even life itself before

9

10

the enactment of R.A. 9346 ) is at stake.

What is the objective of the right to speedy

disposition of cases?

The right to speedy disposition of cases is

not merely hinged towards the objective of

spurring dispatch in the administration of

justice but also to prevent the oppression of

the citizen by holding a criminal prosecution

suspended over him for an indefinite time.

Akin to the right to speedy trial, its salutary

objective is to assure that an innocent

person may be free from the anxiety and

expense of litigation or, if otherwise, of

having his guilt determined within the

shortest possible time compatible with the

presentation

and

consideration

of

whatsoever legitimate defense he may

interpose.11 This looming unrest as well as

the tactical disadvantages carried by the

passage of time should be weighed against

the State and in favor of the individual.

WHEN is the right to speedy disposition

VIOLATED?

Jurisprudence dictates that the right to

speedy disposition is deemed violated only

when the proceedings are attended by

vexatious, capricious, and oppressive

delays; or when unjustified postponements

of the trial are asked for and secured; or

even without cause or justifiable motive, a

long period of time is allowed to elapse

without the party having his case tried.12

9

10

11

12

An Act Prohibiting The Imposition Of Death Penalty In

The Philippines

Sandiganbayan (Second Division) in Criminal Case

No. SB-08-CRM-0266, quoted in People of the

Philippines v. Hon. Sandiganbayan, First Division, et

al., G.R. No. 188165, 11 December 2013.

Mari v. Gonzales, G.R. No. 187728, September 12,

2011, 657 SCRA 414, 423.

Roquero v. Chancellor of UP-Manila, supra.

What are the factors which must be

considered in assessing whether the right

to speedy disposition is violated?

In the determination of whether the

defendant has been denied his right to a

speedy disposition of a case, the following

factors may be considered and balanced:

1. the length of delay;

2. the reasons for the delay;

3. the assertion or failure to assert

such right by the accused; and

4. the prejudice caused by the delay.13

Preparation of the Resolution, not

considered as end of Preliminary

Investigation, for purposes of assessing

violation/non-violation of the right to

speedy disposition of cases.

In Cosculluela, the Supreme Court did not

lend credence to the Sandiganbayans

position that the conduct of preliminary

investigation was terminated as early as

March 27, 2003, or the time when Graft

Investigation Officer Butch E. Caares

prepared the Resolution recommending the

filing of the Information.

According to the High Court, such position

is belied by Section 4, Rule II of the

Administrative Order No. 07 dated April 10,

1990, otherwise known as the Rules of

Procedure of the Office of the Ombudsman,

which provides:

SEC. 4. Procedure The preliminary

investigation of cases falling under the

jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan and

Regional Trial Courts shall be conducted in

the manner prescribed in Section 3, Rule

112 of the Rules of Court, subject to the

following provisions:

xxx

xxx

xxx

No information may be filed and no

complaint may be dismissed without the

written authority or approval of the

13

Id., at 733.

ODESSA GRACE E. GONZAGA | Last Updated on 09 December 2016.

Ombudsman in cases falling within the

jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan, or of the

proper Deputy Ombudsman in all other

cases. (emphasis and underscoring supplied)

The above-cited provision readily reveals

that there is no complete resolution of a case

under preliminary investigation until the

Ombudsman approves the investigating

officers recommendation to either file an

Information with the SB or to dismiss the

complaint. Therefore, the preliminary

investigation

proceedings

were

not

terminated upon Caares preparation of the

Resolution and Information on 27 March

2003 but rather, only at the time Acting

Ombudsman Orlando C. Casimiro finally

approved the same for filing with the SB. In

this regard, the proceedings were terminated

only on 21 May 2009, or almost eight (8)

years after the filing of the complaint.

Finally, the Office of the Ombudsman

should create a system of accountability in

order to ensure that cases before it are

resolved with reasonable dispatch and to

equally expose those who are responsible for

its delays, as it ought to determine in this

case.

Can the Sandiganbayan use the excuse the

delay

in

preliminary

investigation

proceedings of the Ombudsman by the

fact that the case had to undergo careful

review and revision through the different

levels therein, in addition to the steady

stream of cases which the Ombudsman

had to resolve?

NO. The Office of the Ombudsman was

created under the mantle of the Constitution,

mandated to be the protector of the people

and as such, required to act promptly on

complaints filed in any form or manner

against officers and employees of the

Government, or of any subdivision, agency

or instrumentality thereof, in order to

promote efficient service.14 This great

responsibility cannot be simply brushed

aside by ineptitude.

Precisely, the Office of the Ombudsman has

the inherent duty not only to carefully go

through the particulars of case but also to

resolve the same within the proper length of

time. Its dutiful performance should not

only be gauged by the quality of the

assessment but also by the reasonable

promptness of its dispensation. Thus,

barring any extraordinary complication,

such as the degree of difficulty of the

questions involved in the case or any event

external thereto that effectively stymied its

normal work activity any of which have

not been adequately proven by the

prosecution in the case at bar there appears

to be no justifiable basis as to why the

Office of the Ombudsman could not have

earlier resolved the preliminary investigation

proceedings.15

Notice of the on-going investigation or

termination

thereof,

necessary

in

determining assertion or non-assertion by

the accused of its right to speedy

disposition.

In the Cosculluela case, the Supreme Court

found that the accused cannot be faulted for

their alleged failure to assert their right to

speedy disposition of cases.

Records show that accused could not have

urged the speedy resolution of their case

because they were unaware that the

investigation against them was still ongoing. They were only informed of the 27

March 2003 Resolution and Information

against them only after the lapse of six (6)

long years, or when they received a copy of

14

15

Enriquez v. Office of the Ombudsman, G.R. Nos.

174902-06, February 15, 2008, 545 SCRA 627-630.

Rafael L. Coscolluela v. Sanbiganbayan (First

Division) and People of the Philippines, G.R. No.

191411, 15 July 2013.

ODESSA GRACE E. GONZAGA | Last Updated on 09 December 2016.

the latter after its filing with the SB on 19

June 2009.

In this regard, they could have reasonably

assumed that the proceedings against them

have already been terminated. This serves

as a plausible reason as to why accused

never followed-up on the case altogether.

Instructive on this point is the Courts

observation in Duterte v. Sandiganbayan,16

to wit:

Petitioners in this case, however, could

not have urged the speedy resolution of

their case because they were completely

unaware that the investigation against

them was still on-going. Peculiar to this

case, we reiterate, is the fact that petitioners

were merely asked to comment, and not file

counter-affidavits which is the proper

procedure to follow in a preliminary

investigation.

After

giving

their

explanation and after four long years of

being in the dark, petitioners, naturally,

had reason to assume that the charges

against them had already been dismissed.

On the other hand, the Office of the

Ombudsman failed to present any plausible,

special or even novel reason which could

justify the four-year delay in terminating its

investigation. Its excuse for the delay the

many layers of review that the case had to

undergo and the meticulous scrutiny it had

to entail has lost its novelty and is no

longer appealing, as was the invocation in

the Tatad case. The incident before us does

not involve complicated factual and legal

issues, specially (sic) in view of the fact that

the subject computerization contract had

been mutually cancelled by the parties

thereto even before the Anti-Graft League

filed its complaint. (emphasis and

underscoring supplied)

Being the respondents in the preliminary

investigation proceedings, it was not the

accuseds duty to follow up on the

prosecution of their case. Conversely, it was

the

Office

of

the

Ombudsmans

responsibility to expedite the same within

the bounds of reasonable timeliness in view

of its mandate to promptly act on all

complaints lodged before it. As pronounced

in the case of Barker v. Wingo:17

A defendant has no duty to bring himself to

trial; the State has that duty as well as the

duty of insuring that the trial is consistent

with due process.

Reckless

Reasoning:

Ombudsmans

authority is vested by law, hence,

Ombudsman cannot be divested thereof

by mere claim of delay.

The argument that the authority of the

Ombudsman is not divested by the claimed

delay in filing the information as this

authority is vested by law is a reckless

reasoning that only shows that while

admitting there was undue delay in the

disposition of the case, it could still proceed

with its information to charge the accused.

In People v. Hon. Sandiganbayan, First

Division,18 the Supreme Court quoted the

Sandiganbayan (Second Division) 19, when

the latter said:

The prosecution need not be reminded of the

uniform ruling of the Honorable Supreme

Court dismissing the cases of Tatad,

Angchangco, Duterte and other cases for

transgressing the constitutional rights of the

accused to a speedy disposition of cases. To

argue that the authority of the Ombudsman

is not divested by the claimed delay in filing

the information xxx is to limit the power of

the Court to act on blatant transgression of

the constitution.

It must be remembered that delay in

instituting prosecutions is not only

productive of expense to the State, but

of peril to public justice in the

attenuation and distortion, even by mere

natural lapse of memory, of testimony.

It is the policy of the law that

17

18

16

G.R. No. 130191, 27 April 1998 (352 Phil. 557, 582583).

19

407 U.S. 514 (1972).

People of the Philippines v. Hon. Sandiganbayan, First

Division, et al., G.R. No. 188165, 11 December 2013.

In Criminal Case No. SB-08-CRM-0266.

ODESSA GRACE E. GONZAGA | Last Updated on 09 December 2016.

prosecutions should be prompt, and that

statutes, enforcing such promptitude

should be vigorously maintained. They

are not merely acts of grace, but checks

imposed by the State upon itself, to

exact vigilant activity from its

subalterns, and to secure for criminal

trials the best evidence that can be

obtained. 20

In determining violation of the right to

speedy disposition, a Fact-Finding

Investigation

conducted

by

an

Ombudsman Field Investigation Office

(FIO) should not deemed separate from

the preliminary investigation conducted

the Office of the Ombudsman.

The guarantee of the speedy disposition of

cases under Section 16 of Article III of the

Constitution applies to all cases pending

before all judicial, quasi-judicial or

administrative bodies.

Thus, the factfinding investigation should not be deemed

separate from the preliminary investigation

conducted by the Office of the Ombudsman

if the aggregate time spent for both

constitutes inordinate and oppressive delay

in the disposition of any case. 21

It is baseless to capitalize on what the

Ombudsman supposedly did in the process

of the fact-finding stance; and then

reasoning out as if clutching on straws that

the sequences of events should excuse it

from lately filing the information. But it

took the Ombudsman six (6) years to

conduct the said fact-finding investigation,

and then unabashedly it argues that is not

part of the preliminary investigation.

Determining probable cause should usually

take no more than ninety (90) days precisely

20

21

Sandiganbayan (Second Division) in Criminal Case

No. SB-08-CRM-0266, quoted in People of the

Philippines v. Hon. Sandiganbayan, First Division, et

al., G.R. No. 188165, 11 December 2013.

People of the Philippines v. Hon. Sandiganbayan, First

Division, et al., G.R. No. 188165, 11 December 2013.

because it only involves finding out whether

there are reasonable grounds to believe that

the persons charged could be held for trial or

not. It does not require sifting through and

meticulously examining every piece of

evidence to ascertain that they are enough to

convict the persons involved beyond

reasonable doubt. That is already the

function of the Courts.

The conclusion thus, that the long waiting of

six (6) years for the Office of the

Ombudsman to resolve the simple case of

Robbery is clearly an inordinate delay,

blatantly intolerable, and grossly prejudicial

to the constitutional right of speedy

disposition of cases, easily commands

assent. Nonetheless, it must be made clear,

that issuing this ruling is not making nor

indulging in mere mathematical reckoning

of the time involved. 22

What test should be applied in assessing

the prejudice caused by the delay?

22

Sandiganbayan (Second Division) in Criminal Case

No. SB-08-CRM-0266, quoted in People of the

Philippines v. Hon. Sandiganbayan, First Division, et

al., G.R. No. 188165, 11 December 2013.

In the same case, the Supreme Court, on the issue of

inordinate delay, held that:

There was really no sufficient justification

tendered by the State for the long delay of

more than five years in bringing the charges

against the respondents before the proper

court. On the charge of robbery under

Article 293 in relation to Article 294 of

the Revised Penal Code, the preliminary

investigation would not require more

than five years to ascertain the relevant

factual and legal matters. The basic

elements of the offense, that is, the

intimidation or pressure allegedly exerted

on Cong. Jimenez, the manner by which

the money extorted had been delivered,

and the respondents had been identified as

the perpetrators, had been adequately

bared before the Office of the Ombudsman.

x x x.

ODESSA GRACE E. GONZAGA | Last Updated on 09 December 2016.

Closely related to the length of delay is the

reason or justification of the State for such

delay. Different weights should be assigned

to different reasons or justifications invoked

by the State. For instance, a deliberate

attempt to delay the trial in order to hamper

or prejudice the defense should be weighted

heavily against the State. Also, it is

improper for the prosecutor to intentionally

delay to gain some tactical advantage over

the defendant or to harass or prejudice him.

On the other hand, the heavy case load of

the prosecution or a missing witness should

be weighted less heavily against the State. x

x x (emphasis supplied; citations omitted)

The test that should be applied in assessing

the prejudice caused by the delay is the

balancing test.

In the context of the right to a speedy trial,

the Court in Corpuz v. Sandiganbayan23

illumined:

A balancing test of applying societal

interests and the rights of the accused

necessarily compels the court to approach

speedy trial cases on an ad hoc basis.

x x x Prejudice should be assessed in the

light of the interest of the defendant that the

speedy trial was designed to protect,

namely: to prevent oppressive pre-trial

incarceration; to minimize anxiety and

concerns of the accused to trial; and to limit

the possibility that his defense will be

impaired. Of these, the most serious is the

last, because the inability of a defendant

adequately to prepare his case skews the

fairness of the entire system. There is also

prejudice if the defense witnesses are

unable to recall accurately the events of

the distant past. Even if the accused is not

imprisoned prior to trial, he is still

disadvantaged by restraints on his liberty

and by living under a cloud of anxiety,

suspicion and often, hostility. His

financial resources may be drained, his

association is curtailed, and he is

subjected to public obloquy.

Unreasonable delay of more than ten (10)

years, violative of the right to speedy

disposition; Reorganization not a valid

excuse; speedy disposition applies also

when the case is already submitted for

decision.

In Licaros v. the Sandiganbayan,24 the

Supreme Court held:

The unreasonable delay of more than ten

(10) years to resolve a criminal case, without

fault on the part of the accused and despite

his earnest effort to have his case decided,

violates the constitutional right to the speedy

disposition of a case. Unlike the right to a

speedy trial, this constitutional privilege

applies not only during the trial stage, but

also when the case has already been

submitted for decision.

Delay is a two-edge sword. It is the

government that bears the burden of proving

its case beyond reasonable doubt. The

passage of time may make it difficult or

impossible for the government to carry its

burden. The Constitution and the Rules do

not require impossibilities or extraordinary

efforts, diligence or exertion from courts or

the prosecutor, nor contemplate that such

right shall deprive the State of a reasonable

opportunity of fairly prosecuting criminals.

As held in Williams v. United States, for the

government to sustain its right to try the

accused despite a delay, it must show two

things: (a) that the accused suffered no

serious prejudice beyond that which ensued

from the ordinary and inevitable delay; and

(b) that there was no more delay than is

reasonably attributable to the ordinary

processes of justice.

xxx

Corpuz v. Sandiganbayan, 484 Phil. 899, 917-919

(2004)

xxx

The failure of the Sandiganbayan to decide

the case even after the lapse of more than

ten years after it was submitted for decision

involves more than just a mere

procrastination in the proceedings. From the

explanation given by the Sandiganbayan, it

appears that the case was kept in idle

slumber, allegedly due to reorganizations in

the divisions and the lack of logistics and

facilities for case records. Had it not been

for the filing of this Petition for Mandamus,

petitioner would not have seen any

development in his case, much less the

eventual disposition thereof. The case

24

23

xxx

Abelardo B. Licaros v. The Sandiganbayan and The

Special Prosecutor, G.R. No. 145851, 22 November

2001.

ODESSA GRACE E. GONZAGA | Last Updated on 09 December 2016.

remains unresolved up to now, with only

respondent courts assurance that at this time

work is being done on the case for the

preparation and finalization of the decision

complaint by stating that no political

motivation appears to have tainted the

prosecution of the case.

xxx

xxx

xxx

xxx

xxx

xxx

In sum, we hold that the dismissal of the

criminal case against petitioner for violation

of his right to a speedy disposition of his

case is justified by the following

circumstances: (1) the 10-year delay in the

resolution of the case is inordinately long;

(2) petitioner has suffered vexation and

oppression by reason of this long delay; (3)

he did not sleep on his right and has in fact

consistently asserted it, (4) he has not

contributed in any manner to the long delay

in the resolution of his case, (5) he did not

employ any procedural dilatory strategies

during the trial or raised on appeal or

certiorari any issue to delay the case, (6) the

Sandiganbayan did not give any valid reason

to justify the inordinate delay and even

admitted that the case was one of those that

got buried during its reorganization, and (7)

petitioner was merely charged as an

accessory after the fact.

We cannot accept the Special Prosecutors

ratiocination. It is the duty of the prosecutor

to speedily resolve the complaint, as

mandated by the Constitution, regardless of

whether the petitioner did not object to the

delay or that the delay was with his

acquiescence provided that it was not due to

causes directly attributable to him.

Consequently,

we

rule

that

the

Sandiganbayan gravely abused its discretion

in not quashing the information for violation

of petitioners Constitutional right to the

speedy disposition of the case in the level of

the Special Prosecutor, Office of the

Ombudsman.

For too long, petitioner has suffered in

agonizing anticipation while awaiting the

ultimate resolution of his case. The

inordinate and unreasonable delay is

completely

attributable

to

the

Sandiganbayan. No fault whatsoever can be

ascribed to petitioner or his lawyer. It is now

time to enforce his constitutional right to

speedy disposition and to grant him speedy

justice.

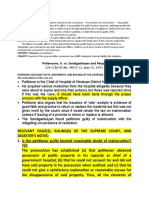

May the fact that no political motivation

attended the prosecution be validly raised

against an alleged violation of the right to

speedy disposition?

No. In Cervantes v. The Sandiganbayan

(First Division), et al.,25 the Supreme Court

held that there was violation of the right to

speedy disposition of cases, after finding

that:

The Special Prosecutor try to justify the

inordinate delay in the resolution of the

25

Elpidio C. Cervantes v. The Sandiganbayan (First

Division), The Special Prosecutor, and Pedro

Almendras, G.R. No. 108595, 18 May 1999.

ODESSA GRACE E. GONZAGA | Last Updated on 09 December 2016.

Você também pode gostar

- Criminal Procedure 2018 BarDocumento54 páginasCriminal Procedure 2018 BarelizafaithAinda não há avaliações

- Two Months To File Unjust Vexation ComplaintDocumento2 páginasTwo Months To File Unjust Vexation Complaintyurets929100% (2)

- Notes On Gender and DevelopmentDocumento4 páginasNotes On Gender and DevelopmentDei Gonzaga100% (3)

- Amended AnswerDocumento3 páginasAmended AnswerJoan CarigaAinda não há avaliações

- A.M. No. 12-11-2-SC Guidelines For Decongesting Holding JailsDocumento6 páginasA.M. No. 12-11-2-SC Guidelines For Decongesting Holding JailsDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Prejudicial QuestionDocumento8 páginasPrejudicial QuestioncaseskimmerAinda não há avaliações

- P.D. 968 Probation Law As Amended by PD 1990Documento8 páginasP.D. 968 Probation Law As Amended by PD 1990Dei Gonzaga100% (2)

- OCA-Circular-No.110-2014 Bar Matter No. 2604 Re Clarification Relative To Sections 2 and 13 Rule III of The 2004 Rules On Notarial PracticeDocumento2 páginasOCA-Circular-No.110-2014 Bar Matter No. 2604 Re Clarification Relative To Sections 2 and 13 Rule III of The 2004 Rules On Notarial PracticeDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Doj NPS ManualDocumento40 páginasDoj NPS Manualed flores92% (13)

- Annotation Complex Crime of Kidnapping With MurderDocumento10 páginasAnnotation Complex Crime of Kidnapping With MurderPia Christine BungubungAinda não há avaliações

- Anti-Trafficking of Persons Act of 2003 - RA 9208Documento11 páginasAnti-Trafficking of Persons Act of 2003 - RA 9208Ciara NavarroAinda não há avaliações

- Investigation Data Form: Office of The Provincial Prosecutor of Rosario, La UnionDocumento1 páginaInvestigation Data Form: Office of The Provincial Prosecutor of Rosario, La Unionmikejosephbarcena100% (2)

- R.A. No. 9262 Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004Documento16 páginasR.A. No. 9262 Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004Dei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines Archiving CasesDocumento2 páginasGuidelines Archiving CasesidemsonamAinda não há avaliações

- R. A. No. 10592 An Act Amending Articles 29 92 97 98 and 99 of The RPCDocumento3 páginasR. A. No. 10592 An Act Amending Articles 29 92 97 98 and 99 of The RPCDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Administrative Order No IRR of Ra 10023Documento6 páginasAdministrative Order No IRR of Ra 10023mark christianAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Table of R.A. 10951 and RPC ProvisionsDocumento51 páginasComparative Table of R.A. 10951 and RPC ProvisionsDei Gonzaga98% (88)

- Ambil v. Sandiganbayan (Case Digest)Documento1 páginaAmbil v. Sandiganbayan (Case Digest)Dredd LelinaAinda não há avaliações

- Regional Trial Court: Crim Cases No. 657Documento3 páginasRegional Trial Court: Crim Cases No. 657Levy DaceraAinda não há avaliações

- Municipal Court Ruling on Demurrer to Evidence in Grave Oral Defamation CaseDocumento8 páginasMunicipal Court Ruling on Demurrer to Evidence in Grave Oral Defamation CaseBobby SuarezAinda não há avaliações

- TITLE 7 - Digest Crim LawDocumento4 páginasTITLE 7 - Digest Crim LawLourie Mae CalopeAinda não há avaliações

- Inquest, Remedies Available Before and After The Filing of An InformationDocumento2 páginasInquest, Remedies Available Before and After The Filing of An InformationNikkoCataquizAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisdiction of CourtsDocumento2 páginasJurisdiction of CourtsMichael Parreño Villagracia100% (3)

- Consti 2 - Speedy DispositionDocumento13 páginasConsti 2 - Speedy DispositionlouAinda não há avaliações

- ARTICLE 212 RPC Disini vs. SandiganbayanDocumento3 páginasARTICLE 212 RPC Disini vs. SandiganbayanPauline Macas100% (1)

- Sample ComplaintDocumento3 páginasSample ComplaintInais GumbAinda não há avaliações

- Risos-Vidal v. COMELECDocumento2 páginasRisos-Vidal v. COMELECNeil BorjaAinda não há avaliações

- A. Anti-Piracy and Anti-Highway Robbery (P.D.532)Documento22 páginasA. Anti-Piracy and Anti-Highway Robbery (P.D.532)JvnRodz P GmlmAinda não há avaliações

- CRIMES AGAINST CHASTITY SEODocumento4 páginasCRIMES AGAINST CHASTITY SEOLyn OlitaAinda não há avaliações

- Rules of Admissibility: Common Reputation and Res GestaeDocumento3 páginasRules of Admissibility: Common Reputation and Res GestaeDiana Rose DalitAinda não há avaliações

- Municipal Court Summons Rene Hison vs Jorge Gonzales Exor BankDocumento2 páginasMunicipal Court Summons Rene Hison vs Jorge Gonzales Exor BankNoel Christopher G. Belleza0% (1)

- Bigamy in Foreign LandsDocumento2 páginasBigamy in Foreign LandsmarcialxAinda não há avaliações

- Matias - Rem1 - Case Digest - CrimPro PDFDocumento86 páginasMatias - Rem1 - Case Digest - CrimPro PDFMichelle Dulce Mariano CandelariaAinda não há avaliações

- Trial Memorandum-Pedro BuhayDocumento4 páginasTrial Memorandum-Pedro BuhayReinaflor TalampasAinda não há avaliações

- Preliminary Investigation ProcessDocumento1 páginaPreliminary Investigation Processmonet_antonioAinda não há avaliações

- Regional Trial CourtDocumento2 páginasRegional Trial CourtJune RudiniAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Law by Judge Campanilla UP Law Center PDFDocumento78 páginasCriminal Law by Judge Campanilla UP Law Center PDFCessy Ciar Kim100% (1)

- Annotation-Writ of ExecutionDocumento6 páginasAnnotation-Writ of ExecutionNyl AnerAinda não há avaliações

- Conflict of Laws by CoquiaDocumento23 páginasConflict of Laws by CoquiaJaro Mabalot80% (5)

- Concubinage Full TextDocumento70 páginasConcubinage Full TextJAM100% (1)

- Remedial Law 1 Case DigestDocumento69 páginasRemedial Law 1 Case DigestMike E DmAinda não há avaliações

- Court upholds validity of graft chargesDocumento2 páginasCourt upholds validity of graft chargesSum VelascoAinda não há avaliações

- Continuos Trial Rule, JA, CybercrimeDocumento16 páginasContinuos Trial Rule, JA, CybercrimeRalph Christian Lusanta Fuentes0% (1)

- Jurisdiction of SandiganbayanDocumento2 páginasJurisdiction of SandiganbayanMaria Danice AngelaAinda não há avaliações

- Strategic Performance Management System (SPMS) : Revised Guidelines For The Implementation of ADocumento38 páginasStrategic Performance Management System (SPMS) : Revised Guidelines For The Implementation of AChristineCo100% (2)

- R.A. No. 10389 Recognizance Act of 2012Documento5 páginasR.A. No. 10389 Recognizance Act of 2012Dei Gonzaga100% (1)

- Binay vs. SandiganbayanDocumento1 páginaBinay vs. SandiganbayanAphrAinda não há avaliações

- SC rules on double jeopardyDocumento14 páginasSC rules on double jeopardySbl IrvAinda não há avaliações

- Memorandum For The Prosecution 1 PDFDocumento3 páginasMemorandum For The Prosecution 1 PDFJacel Anne DomingoAinda não há avaliações

- Regional Trial Court Branch 28 criminal caseDocumento2 páginasRegional Trial Court Branch 28 criminal caseVal Justin DeatrasAinda não há avaliações

- Theft Case Against House HelpDocumento4 páginasTheft Case Against House HelpMelencio Silverio FaustinoAinda não há avaliações

- Motion To Suppress EvidenceDocumento4 páginasMotion To Suppress EvidencePaulo VillarinAinda não há avaliações

- The Meaning of Civil Interdiction in The Philippine LawDocumento2 páginasThe Meaning of Civil Interdiction in The Philippine LawPam G.Ainda não há avaliações

- A.M. No. 99-10-09-SC Resolution Clarifying Guidelines On The Application For and Enforceability of Search WarrantDocumento2 páginasA.M. No. 99-10-09-SC Resolution Clarifying Guidelines On The Application For and Enforceability of Search WarrantDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Briefer On Probable CauseDocumento6 páginasBriefer On Probable CauseDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Sample of Application For Search WarrantDocumento3 páginasSample of Application For Search WarrantBeverly FGAinda não há avaliações

- Election LawsDocumento127 páginasElection Lawsgeritt100% (2)

- Revised Rules On Summary ProcedureDocumento5 páginasRevised Rules On Summary ProcedureFaye AmoradoAinda não há avaliações

- What Is An Affidavit?Documento16 páginasWhat Is An Affidavit?CDT LIDEM JOSEPH LESTERAinda não há avaliações

- Third Party ComplaintDocumento2 páginasThird Party ComplaintJunivenReyUmadhay100% (1)

- Unnotarized Deed of Sale Vis A Vis Land RegistrationDocumento1 páginaUnnotarized Deed of Sale Vis A Vis Land RegistrationAlyk CalionAinda não há avaliações

- Anti FencingDocumento77 páginasAnti FencingMona Red RequillasAinda não há avaliações

- CA 408 Philippine Articles of War, Amended 1985Documento7 páginasCA 408 Philippine Articles of War, Amended 1985Mark TanAinda não há avaliações

- Contract Obligations and Solidary LiabilityDocumento3 páginasContract Obligations and Solidary LiabilityMaria Resper Lagas50% (2)

- Philippines v. Apipa G. Guro Estafa InformationDocumento2 páginasPhilippines v. Apipa G. Guro Estafa InformationMaria Cristina Martinez100% (1)

- People Vs Rillorta DigestDocumento2 páginasPeople Vs Rillorta DigestRussell John Hipolito100% (2)

- Admission by Adverse Party: Rule 26Documento5 páginasAdmission by Adverse Party: Rule 26Diana Rose Constantino100% (2)

- Counter Affidavit PRACDocumento3 páginasCounter Affidavit PRACSong OngAinda não há avaliações

- A.M. No. 01-7-01-SC Rules On Electronic EvidenceDocumento9 páginasA.M. No. 01-7-01-SC Rules On Electronic EvidenceDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Coscoluella V SandiganbayanDocumento2 páginasCoscoluella V SandiganbayanBananaAinda não há avaliações

- Public Disorders: Art. 153 Revised Penal Code. Tumults and Other Disturbances of Public OrderDocumento5 páginasPublic Disorders: Art. 153 Revised Penal Code. Tumults and Other Disturbances of Public Orderjeysonmacaraig100% (2)

- Hot PursuitDocumento66 páginasHot PursuitRex Del ValleAinda não há avaliações

- Oral DefamationDocumento4 páginasOral DefamationRyan Acosta0% (1)

- A.M. No. 12-8-8-SC Judicial Affidavit RuleDocumento6 páginasA.M. No. 12-8-8-SC Judicial Affidavit RuleDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Understand Unjust Vexation LawDocumento3 páginasUnderstand Unjust Vexation LawJ Velasco PeraltaAinda não há avaliações

- Speedy Disposition of CasesDocumento7 páginasSpeedy Disposition of CasesWeng Santos100% (1)

- Arbitrary Detention and Violation of DomicileDocumento3 páginasArbitrary Detention and Violation of DomicileNesuui MontejoAinda não há avaliações

- Regional Trial Court: That On July 1, 2012 in The City of Cagayan de OroDocumento2 páginasRegional Trial Court: That On July 1, 2012 in The City of Cagayan de OroReynaldo Fajardo YuAinda não há avaliações

- Medico Legal Report FormDocumento1 páginaMedico Legal Report FormherbertAinda não há avaliações

- People vs Manuel AcquittalDocumento8 páginasPeople vs Manuel AcquittalNufa Alyha KaliAinda não há avaliações

- 1 People vs. Sandiganbayan (Fifth Division)Documento18 páginas1 People vs. Sandiganbayan (Fifth Division)Miss JAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisdiction: Doctrine of Duplicity of OffensesDocumento10 páginasJurisdiction: Doctrine of Duplicity of Offenses1222Ainda não há avaliações

- Coscolluela V SBDocumento3 páginasCoscolluela V SBJenny A. BignayanAinda não há avaliações

- Coscolluela vs. SandiganbayanDocumento1 páginaCoscolluela vs. SandiganbayanSincerely YoursAinda não há avaliações

- 03 Coscolluela V SandiganbayanDocumento2 páginas03 Coscolluela V SandiganbayanfcnrrsAinda não há avaliações

- Speedy Disposition JurisDocumento4 páginasSpeedy Disposition JurisSamJadeGadianeAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 201834 Dizon vs. Naess Shipping Philippines, Inc.Documento14 páginasG.R. No. 201834 Dizon vs. Naess Shipping Philippines, Inc.Dei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- R.A. No. 10372Documento6 páginasR.A. No. 10372Dei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Article IV: CitizenshipDocumento33 páginasArticle IV: CitizenshipDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Administrative Circular on Special Treatment of Minor DetaineesDocumento2 páginasAdministrative Circular on Special Treatment of Minor DetaineesDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Administrative Circular No. 13 Guidelines On The Issuance of Search WarrantDocumento3 páginasAdministrative Circular No. 13 Guidelines On The Issuance of Search WarrantDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- RA 10883 - The New Anti-Carnapping Act of 2016Documento2 páginasRA 10883 - The New Anti-Carnapping Act of 2016Anonymous KgPX1oCfrAinda não há avaliações

- Indeterminate Sentence LawDocumento4 páginasIndeterminate Sentence LawtagabantayAinda não há avaliações

- Intellectual Property ApplicationsDocumento6 páginasIntellectual Property ApplicationsmisskangAinda não há avaliações

- Examination Guidelines For Pharmaceutical Patent Applications Involving Known SubstancesDocumento28 páginasExamination Guidelines For Pharmaceutical Patent Applications Involving Known SubstancesDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- The Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations For Patents, Utility Models and Industrial DesignsDocumento54 páginasThe Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations For Patents, Utility Models and Industrial DesignsDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Rights of Persons Arrested or Detained ActDocumento2 páginasRights of Persons Arrested or Detained ActDavid Sibbaluca MaulasAinda não há avaliações

- Article 3 Bill of RightsDocumento3 páginasArticle 3 Bill of RightsAkoSi ChillAinda não há avaliações

- Tax-Related Provisions of The IRR On The Tourism Act of 2009Documento4 páginasTax-Related Provisions of The IRR On The Tourism Act of 2009Dei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- What Individual Employers Need To Know About The Kasamabahay LawDocumento3 páginasWhat Individual Employers Need To Know About The Kasamabahay LawDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- 14 Disini vs. Sandiganbayan and PeopleDocumento2 páginas14 Disini vs. Sandiganbayan and PeopleJOHN FLORENTINO MARIANOAinda não há avaliações

- Carandang v. DesiertoDocumento2 páginasCarandang v. DesiertoJORLAND MARVIN BUCUAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Procedure Holds Departure Orders JurisdictionDocumento36 páginasCriminal Procedure Holds Departure Orders JurisdictionStephanie ArtagameAinda não há avaliações

- Admin Election LawDocumento125 páginasAdmin Election LawJovenil BacatanAinda não há avaliações

- Research On PreTrialDocumento3 páginasResearch On PreTrialCzarina RubicaAinda não há avaliações

- AdminkasoDocumento42 páginasAdminkasoMark Ian Gersalino BicodoAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Procedure Prosecution GuideDocumento11 páginasCriminal Procedure Prosecution GuideMa. Ana Joaquina SahagunAinda não há avaliações

- 1st Assignment in Crim Pro JD 601 Law 203Documento3 páginas1st Assignment in Crim Pro JD 601 Law 203MONTILLA LicelAinda não há avaliações

- Sanchez Leonen IIDocumento16 páginasSanchez Leonen IIBfp Siniloan FS LagunaAinda não há avaliações

- PEOPLE Vs FOURTH DIVISIONDocumento3 páginasPEOPLE Vs FOURTH DIVISIONRina GonzalesAinda não há avaliações

- Merencillo v. PeopleDocumento9 páginasMerencillo v. PeoplePamela BalindanAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs Benjamin Romualdez GR 166510 April 29, 2009Documento23 páginasPeople Vs Benjamin Romualdez GR 166510 April 29, 2009Jacquilou Gier MacaseroAinda não há avaliações

- SC upholds constitutionality of Anti-Plunder Law in Estrada caseDocumento2 páginasSC upholds constitutionality of Anti-Plunder Law in Estrada caseMariefe Nuñez AraojoAinda não há avaliações

- Crimpro NotesDocumento112 páginasCrimpro NotesJustineAinda não há avaliações

- Upreme Onrt::fflanilaDocumento16 páginasUpreme Onrt::fflanilaJanMikhailPanerioAinda não há avaliações

- Bayani Subido JR Vs Sandiganbayan Et AlDocumento5 páginasBayani Subido JR Vs Sandiganbayan Et AlJoshua Janine LugtuAinda não há avaliações

- Peñanueva, Jr. vs. Sandiganbayan, 224 SCRA 86 No. 98000-02, June 30, 1993Documento2 páginasPeñanueva, Jr. vs. Sandiganbayan, 224 SCRA 86 No. 98000-02, June 30, 1993RaffaAinda não há avaliações

- Case SummaryDocumento14 páginasCase SummaryMagr EscaAinda não há avaliações

- Rule 117 Motion QuashedDocumento3 páginasRule 117 Motion QuashedKobe Lawrence VeneracionAinda não há avaliações