Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Briefer On Probable Cause

Enviado por

Dei Gonzaga0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

264 visualizações6 páginasResearch on Cases decided by the Supreme Court of the Philippines re Cases heard by the Sandiganbayan with "Probable Cause" as issue.

Título original

Briefer on Probable Cause

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoResearch on Cases decided by the Supreme Court of the Philippines re Cases heard by the Sandiganbayan with "Probable Cause" as issue.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

264 visualizações6 páginasBriefer On Probable Cause

Enviado por

Dei GonzagaResearch on Cases decided by the Supreme Court of the Philippines re Cases heard by the Sandiganbayan with "Probable Cause" as issue.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 6

[RESEARCH ON PROBABLE CAUSE] December 15, 2016

Determination of probable cause in the

OMBUDSMAN and in the SANDIGANBAYAN:

EXECUTIVE and JUDICIAL determination

There are two kinds of determination of

probable cause: executive and judicial.

The executive determination of probable

cause is one made during preliminary

investigation. It is a function that properly

pertains to the public prosecutor who is

given a broad discretion to determine

whether probable cause exists and to charge

those whom he believes to have committed

the crime as defined by law and thus should

be held for trial. Otherwise stated, such

official has the quasi-judicial authority to

determine whether or not a criminal case

must be filed in court. 1 Whether or not that

function has been correctly discharged by

the public prosecutor, i.e., whether or not he

has made a correct ascertainment of the

existence of probable cause in a case, is a

matter that the trial court itself does not and

may not be compelled to pass upon.2

The judicial determination of probable

cause, on the other hand, is one made by the

judge to ascertain whether a warrant of

arrest should be issued against the accused.

The judge must satisfy himself that based on

the evidence submitted, there is necessity for

placing the accused under custody in order

not to frustrate the ends of justice. 3

Thus, absent a finding that an information is

invalid on its face or that the prosecutor

committed manifest error or grave abuse of

discretion, a judges determination of

probable cause is limited only to the judicial

kind or for the purpose of deciding whether

the arrest warrants should be issued against

the accused.4

Judiciarys Standing Policy: Noninterference by courts of the investigatory

and prosecutor powers

The Sandiganbayan and all courts for that

matter should always remember the

judiciarys standing policy on noninterference in the Office of the

Ombudsmans

exercise

of

its

constitutionally mandated powers. This

policy is based not only upon respect for the

investigatory and prosecutory powers

granted by the Constitution to the Office of

the Ombudsman but upon practicality as

well, considering that otherwise, the

functions of the courts will be grievously

hampered

by

innumerable

petitions

regarding complaints filed before it, and in

much the same way that the courts would be

extremely swamped if they were to be

compelled to review the exercise of

discretion on the part of the prosecutors each

time they decide to file an information in

court or dismiss a complaint by a private

complainant.5

A similar ruling is made in Redulla v. The

Hon. Sandiganbayan (First Division), et

al.,6 where the Supreme Court said:

This Court has almost always adopted, quite

aptly, a policy of non-interference in the

exercise

of

the

Ombudsmans

constitutionally mandated powers. This rule

is based not only upon respect for the

investigatory and prosecutory powers

granted by the Constitution to the Office of

4

5

2

3

People of the Philippines vs. Jessie B. Castillo and

Felicito R. Mejia, G.R. No. 171188, 19 June 2009,

citing Paderanga v. Drilon, G.R. No. 96080, 19 April

1991, 196 SCRA 86, 90.

Id., citing Roberts, Jr. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No.

113930, 05 March 1996, 254 SCRA 307, 350.

Id., citing Ho v. People, G.R. Nos. 106632 & 106678,

October 9, 1997, 280 SCRA 365, 380.

People of the Philippines vs. Jessie B. Castillo and

Felicito R. Mejia, G.R. No. 171188, 19 June 2009.

Id.,, citing Go v. Fifth Division, Sandiganbayan, G.R.

No. 172602, April 13, 2007, (521 SCRA 293) and

Andres v. Cuevas, G.R. No. 150869, 09 June 2005,

460 SCRA 32

TEOTIMO M. REDULLA v. THE HON.

SANDIGANBAYAN (FIRST DIVISION), THE OFFICE

OF THE OMBUDSMAN, and THE OFFICE OF THE

SPECIAL PROSECUTOR, G.R. No. 167973 28

February 2007

Ut In Omnibus Glorificetur Dei | ATTY. ODESSA GRACE E. GONZAGA

the Ombudsman but upon practicality as

well. Otherwise, the functions of the courts

will be grievously hampered by innumerable

petitions x x x with regard to complaints

filed before it, in much the same way that

the courts would be extremely swamped if

they were compelled to review the exercise

of discretion on the part of the fiscals, or

prosecuting attorneys, each time they decide

to file an information in court or dismiss a

complaint by a private complainant. 7

2. The preliminary inquiry made by

a prosecutor does not bind the

judge. It merely assists him in

making the determination of

probable cause. It is the report, the

affidavits, the transcripts of

stenographic notes, if any, and all

other

supporting

documents

behind

the

prosecutors

certification which are material in

assisting the judge in his

determination of probable cause;

and

Significance

of

the

OMBUDSMANs

certification in the SBs determination of

probable cause.

3. Judges and prosecutors alike

should distinguish the preliminary

inquiry

which

determines

probable cause for the issuance of

a warrant of arrest from the

preliminary investigation proper

which ascertains whether the

offender should be held for trial or

be released. Even if the two

inquiries be made in one and the

same proceeding, there should be

no

confusion

about

their

objectives. The determination of

probable cause for purposes of

issuing the warrant of arrest is

made by the judge. The

preliminary investigation proper

whether or not there is reasonable

ground to believe that the accused

is guilty of the offense charged

and, therefore, whether or not he

should be subjected to the

expense,

rigors

and

embarrassment of trial is the

function of the prosecutor.

May the SB rely solely on the

Ombudsmans certification of probable

cause?

NO. In Sales v. Sandiganbayan (4th

Division), et al.8, the Supreme Court had the

occasion to rule that:

x x x [I]t was patent error for the

Sandiganbayan to have relied purely on the

Ombudsmans certification of probable

cause given the prevailing facts of this case

much more so in the face of the latters

flawed report and one-sided factual findings.

In the order of procedure for criminal cases,

the task of determining probable cause for

purposes of issuing a warrant of arrest is a

responsibility which is exclusively reserved

by the Constitution to judges.9

Stated differently, while the task of

conducting a preliminary investigation is

assigned either to an inferior court

magistrate or to a prosecutor, 11 only a

judge may issue a warrant of arrest. When

the preliminary investigation is conducted

by an investigating prosecutor, in this

case the Ombudsman, 12 the determination

of probable cause by the investigating

prosecutor cannot serve as the sole basis

for the issuance by the court of a warrant

of arrest. This is because the court with

whom the information is filed is tasked to

make its own independent determination

People v. Inting10 clearly delineated the

features of this constitutional mandate, viz:

1. The determination of probable

cause is a function of the judge; it

is not for the provincial fiscal or

prosecutor to ascertain. Only the

judge and the judge alone makes

this determination;

7

8

9

10

Citing Nava v. Commission on Audit, 419 Phil. 544,

553 (2001).

Reynolan T. Sales v. Sandiganbayan (4th Division),

Ombudsman, People of the Philippines and Thelma

Benemerito, G.R. No. 143802, 16 November 2001.

Article III, Section 2, Constitution.

187 SCRA 788, 792-793 [1990].

11

12

Section 2, Rule 112, 2000 Revised Rules on Criminal

Procedure.

See Section 11 (4), R.A. No. 6770 otherwise known as

the Ombudsman Act of 1989.

of probable cause for the issuance of the

warrant of arrest. Indeed

improbabilities in the prosecution evidence. 13

Certainly

x x x [T]he Judge cannot ignore the

clear words of the 1987 Constitution

which requires x x x probable cause

to be personally determined by the

judge x x x not by any other officer

or person.

x x x probable cause may not be

established simply by showing that a trial

judge subjectively believes that he has good

grounds for his action. Good faith is not

enough. If subjective good faith alone were

the test, the constitutional protection would

be demeaned and the people would be

secure in their persons, houses, papers and

effects only in the fallible discretion of the

judge.14 On the contrary, the probable cause

test is an objective one, for in order that

there be probable cause the facts and

circumstances must be such as would

warrant a belief by a reasonably discreet and

prudent man that the accused is guilty of the

crime which has just been committed.15

xxx

xxx

xxx

The extent of the Judges personal

examination of the report and its

annexes

depends

on

the

circumstances of each case. We

cannot determine beforehand how

cursory or exhaustive the Judges

examination should be. The Judge

has to exercise sound discretion for,

after all, the personal determination

is vested in the Judge by the

Constitution. It can be brief or as

detailed as the circumstances of each

case may require. To be sure, the

Judge must go beyond the

Prosecutors

certification

and

investigation

report

whenever

necessary. He should call for the

complainant

and

witnesses

themselves to answer the courts

probing

questions

when

the

circumstances so require.

xxx

xxx

May a determinative finding on the

presence or absence of the elements of the

offense charged be made during a

determination of probable cause for the

purpose of issuance of warrant of arrest?

NO. In People vs. Castillo & Mejia,16 the

Supreme Court held that:

x x x [I]t was clearly premature on the part

of the Sandiganbayan to make a

determinative finding prior to the parties

presentation of their respective evidence that

there was no bad faith and manifest

partiality on the respondents part and undue

injury on the part of the complainant. x x x

[T]he presence or absence of the elements of

the crime is evidentiary in nature and is a

matter of defense that may be best passed

upon after a full-blown trial on the

17

merits.

x x x

We reiterate that in making the required

personal determination, a Judge is not

precluded from relying on the evidence

earlier gathered by responsible officers.

The extent of the reliance depends on the

circumstances of each case and is subject

to the Judges sound discretion. However,

the Judge abuses that discretion when

having no evidence before him, he issues

a warrant of arrest.

Can the SB require that the prosecution

present all the evidence needed to secure

Duty of the SB in determining probable cause,

when faced with conflicting evidence; Good

faith is not enough.

What the Sandiganbayan should [do when] faced

with x x x a slew of conflicting evidence from

the contending parties, [is] to take careful note of

the contradictions in the testimonies of the

complainants witnesses as well as the

13

14

15

16

17

Allado v. Diokno, 232 SCRA 192 (1994).

Beck v. Ohio, 379 U.S. 89, 85 S Ct. 223, 13 L Ed. 2d

142 (1964).

Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 88 S. Ct. 1868, 20 L Ed. 2d

889 (1968).

People of the Philippines vs. Jessie B. Castillo and

Felicito R. Mejia, G.R. No. 171188, 19 June 2009

Id., citing Go v. Fifth Division, Sandiganbayan,

G.R. No. 172602, 13 April 2007 (521 SCRA 270).

in this case. Although the prosecutor enjoys

the legal presumption of regularity in the

performance of his official duties and

functions, which in turn gives his report the

presumption of accuracy, the Constitution,

we repeat, commands the judge to

personally determine probable cause in the

issuance of warrants of arrest. This Court

has consistently held that a judge fails in his

bounden duty if he relies merely on the

certification or the report of the investigating

officer.21

the conviction of accused upon filing of

the information?

NO. In People vs. Castillo & Mejia,18 the

Supreme Court held that:

"x x x [I]t would be unfair to expect the

prosecution to present all the evidence

needed to secure the conviction of the

accused upon the filing of the information

against the latter. The reason is found in

the nature and objective of a preliminary

investigation. Here, the public prosecutors

do not decide whether there is evidence

beyond reasonable doubt of the guilt of

the person charged; they merely

determine whether there is sufficient

ground to engender a well-founded belief

that a crime has been committed and that

respondent is probably guilty thereof, and

should be held for trial. 19 his, as we said

is the standard. x x x

Are the entire records during the preliminary

investigation required to be submitted and

examined during the judicial determination of

probable cause?

NO. Cojuangco, Jr. v. Sandiganbayan (First

Division)20 teaches that:

It is not required that the complete or entire

records of the case during the preliminary

investigation be submitted to and examined

by the judge. We do not intend to unduly

burden trial courts by obliging them to

examine the complete records of every case

all the time simply for the purpose of

ordering the arrest of an accused. What is

required, rather, is that the judge must have

sufficient supporting documents (such as the

complaint, affidavits, counter-affidavits,

sworn statements of witnesses or transcripts

of stenographic notes, if any) upon which to

make his independent judgment or, at the

very least, upon which to verify the findings

of the prosecutor as to the existence of

probable cause. The point is: he cannot rely

solely and entirely on the prosecutors

recommendation, as Respondent Court did

18

19

20

People of the Philippines vs. Jessie B. Castillo and

Felicito R. Mejia, G.R. No. 171188, 19 June 2009

Id., citing People v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No.

126005, 21 January 1999 (301 SCRA 475, 488).

Eduardo M. Cojuangco, Jr. v. Sandiganbayan (First

Division) and People of the Philippines, G.R. No.

134307, 21 December 1998.

Motion for Judicial Determination of Probable

Cause

Is a motion for judicial determination of

probable cause necessary?

NO. In Leviste v. Hon. Alameda, et al.,22 it

was held that to move the court to conduct a

judicial determination of probable cause is a

mere superfluity, for with or without such

motion, the judge is duty-bound to

personally evaluate the resolution of the

public prosecutor and the supporting

evidence. In fact, the task of the presiding

judge when the Information is filed with the

court is first and foremost to determine the

existence or non-existence of probable cause

for the arrest of the accused.23

What the Constitution underscores is the

exclusive and personal responsibility of the

issuing judge to satisfy himself of the

existence of probable cause. But the judge

is not required to personally examine the

complainant and his witnesses. Following

established doctrine and procedure, he shall

(1) personally evaluate the report and the

supporting documents submitted by the

prosecutor regarding the existence of

probable cause, and on the basis thereof, he

may already make a personal determination

of the existence of probable cause; and (2) if

21

22

23

Citing Ho v. People, 280 SCRA 380, 382 (1997).

Jose Antonio C. Leviste v. Hon. Elmo M. Alameda,

Hon. Raul M. Gonzalez, Hon. Emmanuel Y. Velasco,

Heirs of the late Rafael de las Alas, G.R. No. 182677,

03 August 2010

Leviste, citing Baltazar v. People, G.R. No. 174016, 28

July 2008 (560 SCRA 278, 293).

he is not satisfied that probable cause exists,

he may disregard the prosecutors report and

require the submission of supporting

affidavits of witnesses to aid him in arriving

at a conclusion as to the existence of

probable cause.24 (emphasis supplied)

NO. In Ramiscal, Jr., v. Sandiganbayan (4th

Division),28 the Supreme Court ruled:

We agree with the Sandiganbayans ruling

that the Revised Rules of Criminal

Procedure do not require cases to be set for

hearing to determine probable cause for the

issuance of a warrant for the arrest of the

accused before any warrant may be issued.

Section 6, Rule 112 mandates the judge to

personally evaluate the resolution of the

Prosecutor (in this case, the Ombudsman)

and its supporting evidence, and if he/she

finds probable cause, a warrant of arrest or

commitment order may be issued within 10

days from the filing of the complaint or

Information; in case the Judge doubts the

existence of probable cause, the prosecutor

may be ordered to present additional

evidence within five (5) days from notice.

The provision reads in full:

The rules do not require cases to be set for

hearing to determine probable cause for the

issuance of a warrant of arrest of the accused

before any warrant may be issued.25

Petitioner thus cannot, as a matter of right,

insist on a hearing for judicial determination

of probable cause. Certainly, petitioner

cannot determine beforehand how cursory or

exhaustive the judge's examination of the

records should be since the extent of the

judges examination depends on the exercise

of his sound discretion as the circumstances

of the case require. 26 In one case, the Court

emphatically stated:

SEC. 6. When warrant of arrest may

issue. (a) By the Regional Trial Court.

Within ten (10) days from the filing of

the complaint or information, the judge

shall personally evaluate the resolution

of the prosecutor and its supporting

evidence. He may immediately dismiss

the case if the evidence on record

clearly fails to establish probable cause.

If he finds probable cause, he shall

issue a warrant of arrest, or a

commitment order if the accused has

already been arrested pursuant to a

warrant issued by the judge who

conducted the preliminary investigation

or when the complaint or information

was filed pursuant to section 7 of this

Rule. In case of doubt on the existence

of probable cause, the judge may order

the prosecutor to present additional

evidence within five (5) days from

notice and the issue must be resolved

by the court within thirty (30) days

from the filing of the complaint of

information.29

The periods provided in the Revised Rules

of Criminal Procedure are mandatory, and as

such, the judge must determine the presence

or absence of probable cause within such

periods. The Sandiganbayans determination

of probable cause is made ex parte and is

summary in nature, not adversarial. The

Judge should not be stymied and

distracted from his determination of

probable cause by needless motions for

determination of probable cause filed by

the accused.27 (emphasis and italics

supplied)

Do the rules require that a hearing be set

for the judicial determination of probable

cause?

28

24

25

26

27

Borlongan, Jr. v. Pea, G.R. No. 143591, 23 November

2007 (538 SCRA 235).

Leviste, citing Ramiscal, Jr. v. Sandiganbayan, G.R.

Nos. 169727-28, August 18, 2006, 499 SCRA 375,

398.

Vice Mayor Abdula v. Hon. Guiani, 382 Phil. 757, 776

(2000).

Id., at 399.

29

Brig. Gen. (Ret.) Jose S. Ramiscal, Jr., v.

Sandiganbayan (4th Division) and People of the

Philippines, G.R. Nos. 169727-28, 18 August 2006.

In Administrative Matter No. 05-8-26-SC dated 26

August 2005, which took effect 03 October 2005, the

rule reads:

SEC. 5. When warrant of arrest may issue.

(a) By the Regional Trial Court. Within ten

(10) days from the filing of the complaint or

information, the judge shall personally

The periods provided in the Revised Rules

of Criminal Procedure are mandatory, and as

such, the judge must determine the presence

or absence of probable cause within such

periods. The Sandiganbayans determination

of probable cause is made ex parte and is

summary in nature, not adversarial. The

Judge should not be stymied and distracted

from his determination of probable cause by

needless motions for determination of

probable cause filed by the accused.

evaluate the resolution of the prosecutor

and its supporting evidence. He may

immediately dismiss the case if the

evidence on record clearly fails to establish

probable cause. If he finds probable cause,

he shall issue a warrant of arrest, or a

commitment order when the complaint or

information was filed pursuant to section 6

of this Rule. In case of doubt on the

existence of probable cause, the judge may

order the prosecutor to present additional

evidence within five (5) days from notice

and the issue must be resolved by the court

within thirty (30) days from the filing of the

complaint or information.

Rule 1, Section 2, of the Revised Internal Rules of the

Sandiganbayan provides:

The Rules of Court, resolutions, circulars,

and other issuances promulgated by the

Supreme Court relating to or affecting the

Regional Trial Courts and the Court of

Appeals, insofar as applicable, shall govern

all actions and proceedings filed with the

Sandiganbayan.

Você também pode gostar

- Probable CauseDocumento11 páginasProbable Causerodan parrochaAinda não há avaliações

- Petition For ReviewDocumento5 páginasPetition For ReviewNadine AbenojaAinda não há avaliações

- Final Notes Criminal ProcedureDocumento10 páginasFinal Notes Criminal ProcedureEds NatividadAinda não há avaliações

- Miranda Rights and Obstruction of JusticeDocumento3 páginasMiranda Rights and Obstruction of JusticeOllie EvangelistaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence - Notice of DishoorDocumento4 páginasJurisprudence - Notice of DishoorMarky CieloAinda não há avaliações

- InformationDocumento5 páginasInformationMaanAinda não há avaliações

- Rule 110Documento20 páginasRule 110Jayemc689Ainda não há avaliações

- Sec. 6. When Accused Lawfully Arrested Without Warrant. - When A Person IsDocumento3 páginasSec. 6. When Accused Lawfully Arrested Without Warrant. - When A Person IsChery ValenzuelaAinda não há avaliações

- Pleadings Motion To Quash Search WarrantDocumento3 páginasPleadings Motion To Quash Search WarrantEdcel AndesAinda não há avaliações

- Art 17 Motion To QuashDocumento54 páginasArt 17 Motion To QuashVivi Ko100% (2)

- FG MOTION For Recon SB Quash FINALDocumento12 páginasFG MOTION For Recon SB Quash FINALRG Cruz100% (1)

- No Notice of Dishonor BP 22Documento2 páginasNo Notice of Dishonor BP 22Anonymous 4IOzjRIB1Ainda não há avaliações

- Branch 74 People of The Philippines) ) ) - Versus-) ) For: Viol. of Section 5) RA 9165) ) PPPPP) ) X - XDocumento2 páginasBranch 74 People of The Philippines) ) ) - Versus-) ) For: Viol. of Section 5) RA 9165) ) PPPPP) ) X - XMc GoAinda não há avaliações

- Habeas CorpusDocumento67 páginasHabeas CorpusButch AmbataliAinda não há avaliações

- Juris Motion To Quash Search WarrantDocumento95 páginasJuris Motion To Quash Search WarrantPatoki100% (1)

- Defense of Payment: The Case of People vs. Pilarta For B.P. Blg. 22Documento11 páginasDefense of Payment: The Case of People vs. Pilarta For B.P. Blg. 22Judge Eliza B. Yu100% (3)

- Coa M2014-009 PDFDocumento34 páginasCoa M2014-009 PDFAlvin ComilaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence On Issuance of Letters of AdministrationDocumento3 páginasJurisprudence On Issuance of Letters of AdministrationGlaiza May Mejorada Padlan100% (1)

- Joint Position Paper (For Respondents) : Regional Internal Affairs Service 11Documento2 páginasJoint Position Paper (For Respondents) : Regional Internal Affairs Service 11Be BhingAinda não há avaliações

- Affidavit of BantayanDocumento3 páginasAffidavit of BantayanChris.Ainda não há avaliações

- Writ of Amparo: Questions and Answers: 18shareDocumento6 páginasWrit of Amparo: Questions and Answers: 18shareaaron_cris891Ainda não há avaliações

- Awaiting TrialDocumento6 páginasAwaiting TrialLejla NizamicAinda não há avaliações

- Table of Election RemediesDocumento4 páginasTable of Election RemediesDee WhyAinda não há avaliações

- Verification NLRCDocumento2 páginasVerification NLRCAndre CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Annotation BailDocumento48 páginasAnnotation BailPia Christine BungubungAinda não há avaliações

- Memorandum For Plaintiff: Was An Unfaithful Wife, That She Got Pregnant From Another Man andDocumento6 páginasMemorandum For Plaintiff: Was An Unfaithful Wife, That She Got Pregnant From Another Man andAllisonAinda não há avaliações

- Motion For Recon - Soriano Et - Al.Documento12 páginasMotion For Recon - Soriano Et - Al.Maryknoll MaltoAinda não há avaliações

- COMPLAINT (To PB Pascual-Buenavista)Documento5 páginasCOMPLAINT (To PB Pascual-Buenavista)Richard Gomez100% (1)

- Demurrer To EvidenceDocumento4 páginasDemurrer To EvidenceYanilyAnnVldzAinda não há avaliações

- The Sole Objective of A SuspensionDocumento8 páginasThe Sole Objective of A Suspensionharold ramosAinda não há avaliações

- Motion To Quash Search Warrant: People of The PhilippinesDocumento7 páginasMotion To Quash Search Warrant: People of The PhilippinesSarah Jane-Shae O. SemblanteAinda não há avaliações

- Motion For Summary JudgmentDocumento3 páginasMotion For Summary JudgmentReycy Ruth TrivinoAinda não há avaliações

- Aff of Undertaking - Firearm - Not Involved in Crime - Ebon - Mar 20 2023Documento1 páginaAff of Undertaking - Firearm - Not Involved in Crime - Ebon - Mar 20 2023Geramer Vere DuratoAinda não há avaliações

- Rights of The AccusedDocumento168 páginasRights of The AccusedMrs. WanderLawstAinda não há avaliações

- Motion To Quash Warrant of ArrestDocumento7 páginasMotion To Quash Warrant of ArrestJaseTanAinda não há avaliações

- Admisnitrative Complaint - LegitimasDocumento3 páginasAdmisnitrative Complaint - LegitimasAleks OpsAinda não há avaliações

- Authentication and Proof of DocumentsDocumento29 páginasAuthentication and Proof of DocumentsMa. Danice Angela Balde-BarcomaAinda não há avaliações

- Elements of The Crime of PerjuryDocumento3 páginasElements of The Crime of PerjuryYanyan De LeonAinda não há avaliações

- Katarungan Pambarangay Law Sec 410Documento1 páginaKatarungan Pambarangay Law Sec 410Dan CruzAinda não há avaliações

- States: Court " of For AllDocumento2 páginasStates: Court " of For AllMau Z MacDayAinda não há avaliações

- BP 22Documento3 páginasBP 22Cayen Cervancia CabiguenAinda não há avaliações

- A Lecture On WRITSDocumento87 páginasA Lecture On WRITSmarioAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence On Prima Facie and Probable CauseDocumento2 páginasJurisprudence On Prima Facie and Probable Causeangelosilva1981100% (5)

- Urgent Manifestation - Marisco Vs AmorosoDocumento2 páginasUrgent Manifestation - Marisco Vs AmorosoJoann LedesmaAinda não há avaliações

- Manzanares Et Al - Motion To Quash v.1Documento10 páginasManzanares Et Al - Motion To Quash v.1Alkaios RonquilloAinda não há avaliações

- Labor Law CasesDocumento31 páginasLabor Law CasesFerdinand VillanuevaAinda não há avaliações

- DENR Administrative OrderDocumento5 páginasDENR Administrative OrderEsper LM Quiapos-SolanoAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisprudence On PrescriptionDocumento13 páginasJurisprudence On PrescriptionCeline-Maria JanoloAinda não há avaliações

- Arraignment and PleaDocumento3 páginasArraignment and PleaMeAnn TumbagaAinda não há avaliações

- Ra 9523Documento5 páginasRa 9523diheydsAinda não há avaliações

- Bar 2015 SyllabusDocumento61 páginasBar 2015 SyllabusDeeby PortacionAinda não há avaliações

- MR Omb SampleDocumento5 páginasMR Omb SampleVinz G. VizAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Motion To Quash Search WarrantDocumento8 páginasSample Motion To Quash Search WarrantRamacho, Tinagan, Lu-Bollos & AssociatesAinda não há avaliações

- Sualog Answer To Petition For ReliefDocumento5 páginasSualog Answer To Petition For ReliefjustineAinda não há avaliações

- Alibi Weakest DefenseDocumento3 páginasAlibi Weakest DefenseBernardo L. SantiagoAinda não há avaliações

- Rule 117 Motion To QuashDocumento19 páginasRule 117 Motion To QuashCoreine Imee ValledorAinda não há avaliações

- Court Can Order Automatic Remittance of Child Support: 1 BY ON NOVEMBER 15, 2015Documento4 páginasCourt Can Order Automatic Remittance of Child Support: 1 BY ON NOVEMBER 15, 2015Ren2Ainda não há avaliações

- Admin Law SyllabusDocumento3 páginasAdmin Law SyllabusKriska Herrero TumamakAinda não há avaliações

- Ho Vs PeopleDocumento3 páginasHo Vs Peoplemaricar bernardinoAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Concerned Citizens v. Judge ElmaDocumento3 páginas3 Concerned Citizens v. Judge ElmaryanmeinAinda não há avaliações

- Notes On Gender and DevelopmentDocumento4 páginasNotes On Gender and DevelopmentDei Gonzaga100% (3)

- Right To Speedy Disposition of CasesDocumento7 páginasRight To Speedy Disposition of CasesDei Gonzaga100% (2)

- Comparative Table of R.A. 10951 and RPC ProvisionsDocumento51 páginasComparative Table of R.A. 10951 and RPC ProvisionsDei Gonzaga98% (88)

- A.M. No. 01-7-01-SC Rules On Electronic EvidenceDocumento9 páginasA.M. No. 01-7-01-SC Rules On Electronic EvidenceDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Administrative Circular No. 04-2002 Special Treatment of Minor Detainees and Jail DecongestionDocumento2 páginasAdministrative Circular No. 04-2002 Special Treatment of Minor Detainees and Jail DecongestionDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- A.M. No. 12-8-8-SC Judicial Affidavit RuleDocumento6 páginasA.M. No. 12-8-8-SC Judicial Affidavit RuleDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 201834 Dizon vs. Naess Shipping Philippines, Inc.Documento14 páginasG.R. No. 201834 Dizon vs. Naess Shipping Philippines, Inc.Dei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- OCA-Circular-No.110-2014 Bar Matter No. 2604 Re Clarification Relative To Sections 2 and 13 Rule III of The 2004 Rules On Notarial PracticeDocumento2 páginasOCA-Circular-No.110-2014 Bar Matter No. 2604 Re Clarification Relative To Sections 2 and 13 Rule III of The 2004 Rules On Notarial PracticeDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Administrative Circular No. 13 Guidelines On The Issuance of Search WarrantDocumento3 páginasAdministrative Circular No. 13 Guidelines On The Issuance of Search WarrantDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- RA 10883 - The New Anti-Carnapping Act of 2016Documento2 páginasRA 10883 - The New Anti-Carnapping Act of 2016Anonymous KgPX1oCfrAinda não há avaliações

- Intellectual Property ApplicationsDocumento6 páginasIntellectual Property ApplicationsmisskangAinda não há avaliações

- R.A. No. 9262 Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004Documento16 páginasR.A. No. 9262 Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004Dei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- A.M. No. 99-10-09-SC Resolution Clarifying Guidelines On The Application For and Enforceability of Search WarrantDocumento2 páginasA.M. No. 99-10-09-SC Resolution Clarifying Guidelines On The Application For and Enforceability of Search WarrantDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- P.D. 968 Probation Law As Amended by PD 1990Documento8 páginasP.D. 968 Probation Law As Amended by PD 1990Dei Gonzaga100% (2)

- Tax-Related Provisions of The IRR On The Tourism Act of 2009Documento4 páginasTax-Related Provisions of The IRR On The Tourism Act of 2009Dei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- R. A. No. 10592 An Act Amending Articles 29 92 97 98 and 99 of The RPCDocumento3 páginasR. A. No. 10592 An Act Amending Articles 29 92 97 98 and 99 of The RPCDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- A.M. No. 12-11-2-SC Guidelines For Decongesting Holding JailsDocumento6 páginasA.M. No. 12-11-2-SC Guidelines For Decongesting Holding JailsDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Revised Rules On Summary ProcedureDocumento5 páginasRevised Rules On Summary ProcedureFaye AmoradoAinda não há avaliações

- Come To The TableDocumento2 páginasCome To The TableDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- R.A. No. 10389 Recognizance Act of 2012Documento5 páginasR.A. No. 10389 Recognizance Act of 2012Dei Gonzaga100% (1)

- Let Heaven RejoiceDocumento1 páginaLet Heaven RejoiceDei Gonzaga100% (1)

- Come To The TableDocumento1 páginaCome To The TableDei Gonzaga100% (2)

- Seek Ye FirstDocumento1 páginaSeek Ye FirstDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Mother of ChristDocumento1 páginaMother of ChristDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- What Individual Employers Need To Know About The Kasamabahay LawDocumento3 páginasWhat Individual Employers Need To Know About The Kasamabahay LawDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- O Come Divine MessiahDocumento1 páginaO Come Divine MessiahDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Simeon's CanticleDocumento1 páginaSimeon's CanticleDei GonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs AlfonsoDocumento1 páginaPeople Vs AlfonsoJohnson YaplinAinda não há avaliações

- People v. Legaspi, G.R. No. 136164, April 20, 2001Documento8 páginasPeople v. Legaspi, G.R. No. 136164, April 20, 2001JAinda não há avaliações

- People vs. Bisda DigestDocumento7 páginasPeople vs. Bisda DigestCharmila SiplonAinda não há avaliações

- Case BriefDocumento3 páginasCase BriefShashank JainAinda não há avaliações

- Rule 110 Prosecution of OffensesDocumento3 páginasRule 110 Prosecution of OffensesPatrick SilveniaAinda não há avaliações

- Melo v. PeopleDocumento1 páginaMelo v. PeopleJoycee ArmilloAinda não há avaliações

- 1988 Bar ExaminationDocumento10 páginas1988 Bar ExaminationRodel Cadorniga Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- People v. MayingqueDocumento2 páginasPeople v. MayingqueTootsie GuzmaAinda não há avaliações

- The Beat - Oct-Dec 2011Documento15 páginasThe Beat - Oct-Dec 2011LAPDSouthBureauAinda não há avaliações

- Challenges To VictimDocumento20 páginasChallenges To VictimRicardo LopesAinda não há avaliações

- Russ Hauge's Memo On Officer-Involved ShootingDocumento6 páginasRuss Hauge's Memo On Officer-Involved Shootingkrubenstein591Ainda não há avaliações

- Katarungang Pambarangay - PAO CBRDocumento52 páginasKatarungang Pambarangay - PAO CBRJay-ArhAinda não há avaliações

- PP vs. Hon. Maceda and Javellana - G.R. No. 89591-96 - January 24, 2000Documento3 páginasPP vs. Hon. Maceda and Javellana - G.R. No. 89591-96 - January 24, 2000Nikki BinsinAinda não há avaliações

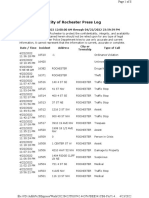

- RPD Daily Incident Report 4/22/22Documento8 páginasRPD Daily Incident Report 4/22/22inforumdocsAinda não há avaliações

- Fernan VS PeopleDocumento1 páginaFernan VS PeopleRene GomezAinda não há avaliações

- UK Home Office: Norfolk Mappa 2007 ReportDocumento7 páginasUK Home Office: Norfolk Mappa 2007 ReportUK_HomeOfficeAinda não há avaliações

- Title 3 - RPC 2 Reyes-Pub OrdDocumento104 páginasTitle 3 - RPC 2 Reyes-Pub OrdEuler De guzmanAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Law Book1 UP Sigma RhoDocumento183 páginasCriminal Law Book1 UP Sigma RhoCrizza CozAinda não há avaliações

- Section 511 of Indian Penal CodeDocumento7 páginasSection 511 of Indian Penal CodeMOUSOM ROYAinda não há avaliações

- Ra 6235Documento1 páginaRa 6235Camille Dawang DomingoAinda não há avaliações

- Paul Andrew Mitchell IndictedDocumento15 páginasPaul Andrew Mitchell IndictedJuan VicheAinda não há avaliações

- Works Cited For Police BrutalityDocumento6 páginasWorks Cited For Police Brutalityapi-383326107Ainda não há avaliações

- 15 People V Jugueta JIMENEZDocumento1 página15 People V Jugueta JIMENEZquasideliksAinda não há avaliações

- Developing and Implementing Parole Systems in IndonesiaDocumento26 páginasDeveloping and Implementing Parole Systems in Indonesiadina julianiAinda não há avaliações

- K.T. Thomas and A.P. Misra, JJDocumento2 páginasK.T. Thomas and A.P. Misra, JJAadhitya NarayananAinda não há avaliações

- People vs. Narvaez, G.R. No. L-33466-67, 20 April 1983Documento1 páginaPeople vs. Narvaez, G.R. No. L-33466-67, 20 April 1983LASAinda não há avaliações

- Sas #7 Cri 170Documento9 páginasSas #7 Cri 170Stephanie SorianoAinda não há avaliações

- West Valley City Police Respond To Mark GeragosDocumento2 páginasWest Valley City Police Respond To Mark GeragosThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Digests (Age of Criminal Liability)Documento5 páginasDigests (Age of Criminal Liability)Juds JDAinda não há avaliações

- Dynamic Business Law 4th Edition Kubasek Test Bank 1Documento83 páginasDynamic Business Law 4th Edition Kubasek Test Bank 1brian100% (39)