Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Bronkiektasis

Enviado por

Halida Batik AlunaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Bronkiektasis

Enviado por

Halida Batik AlunaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Residents Section Pat tern of the Month

Cantin et al.

Bronchiectasis

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Residents Section

Pattern of the Month

Residents

inRadiology

Luce Cantin1

Alexander A. Bankier

Ronald L. Eisenberg

Cantin L, Bankier AA, Eisenberg RL

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is a relatively frequent condition in the United States, with an estimated

prevalence of 4.2 per 100,000 persons 1834 years old and 272 per 100,000 persons 75 years

or older. It is defined as an irreversible localized or diffuse dilatation, usually resulting from

chronic infection, proximal airway obstruction, or congenital bronchial abnormality. On

chest radiographs, bronchiectasis manifests as tram tracks, parallel line opacities, ring opacities, and tubular structures. However, chest radiographs lack sensitivity for detecting mild or

even moderate disease. CT is substantially more sensitive than chest radiography for showing

bronchiectasis, which is characterized by lack of bronchial tapering, bronchi visible in the

peripheral 1 cm of the lungs, and an increased bronchoarterial ratio producing the so-called

signet-ring sign. According to appearance and severity, bronchiectasis can be classified as

cylindric, varicose, or cystic (Fig. 1). The wide differential diagnosis of bronchiectasis can be

substantially narrowed by considering both the anatomic location and the distribution of this

pathology (Fig 2).

Keywords: airway obstruction, bronchiectasis

DOI:10.2214/AJR.09.3053

Received May 15, 2009; accepted after revision

May 26, 2009.

1

All authors: Department of Radiology, Beth Israel

Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, 330

Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215. Address correspondence to R. L. Eisenberg (rleisenb@bidmc.harvard.edu).

WEB

This is a Web exclusive article.

AJR 2009; 193:W158W171

Fig. 1Categories of bronchiectasis.

AD, Normal bronchus (arrow) (A), cylindric bronchiectasis with lack of bronchial tapering (arrow) (B), varicose

bronchiectasis with string-of-pearls appearance (arrow) (C), and cystic bronchiectasis (arrow) (D).

(Fig. 1 continues on next page)

0361803X/09/1933W158

American Roentgen Ray Society

W158

AJR:193, September 2009

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Bronchiectasis

Fig. 1 (continued)Categories of bronchiectasis.

AD, Normal bronchus (arrow) (A), cylindric bronchiectasis with lack of bronchial tapering (arrow) (B), varicose

bronchiectasis with string-of-pearls appearance (arrow) (C), and cystic bronchiectasis (arrow) (D).

Detection of bronchiectasis

Focal bronchiectasis

Congenital bronchial atresia

Extrinsic compression

Endobronchial malignancy

Foreign body

Broncholithiasis

Airway stenosis

Upper lung

predominance

Cystic fibrosis

Sarcoidosis

Postradiation fibrosis

Diffuse bronchiectasis

Peripheral

predominance

Lower lung

predominance

Idiopathic

Postinfectious

Repeated aspiration

Fibrotic lung disease

Posttransplant rejection

Hypogammaglobulinemia

Central

predominance

Right middle lobe and

lingula predominance

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

Mounier-Kuhns syndrome

Williams-Campbell syndrome

Atypical mycobacterial infection (MAI)

Immotile cilia syndrome

Fig. 2Flowchart shows algorithm for evaluation of bronchiectasis. MAI = Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare.

Focal Bronchiectasis

Any cause of airway obstruction can lead to focal bronchiectasis (Fig. 3). In contrast to

diffuse bronchiectasis, focal bronchiectasis requires diagnostic bronchoscopy in almost all

patients.

Bronchial Atresia

The most common cause of congenital focal bronchiectasis is bronchial atresia, characterized by obliteration of a bronchus with distal bronchiectasis, mucoid impaction, and air trapping that is most commonly seen in the left upper lobe (Fig. 4). In this rare lesion, the bronchial tree peripheral to the point of obliteration is patent and the lung parenchyma is overinflated because of collateral air drift.

AJR:193, September 2009

W159

Cantin et al.

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Fig. 3Focal

bronchiectasis

(idiopathic) in left lower

lobe (arrow).

Fig. 4Bronchial atresia.

A, Transverse image of focal bronchiectasis (arrow) distal to bronchial atresia associated with hyperlucency

and hyperexpansion of left lung.

B, Coronal image shows proximal mucoid impaction (arrow), distal bronchiectasis (arrowhead), and widespread

air trapping of left lung.

Extrinsic Compression

Extrinsic compression is an acquired cause of focal bronchiectasis, most commonly caused

by lymphadenopathy, usually from previous granulomatous exposure. Less frequent causes

include sarcoidosis, hilar mass, and metastatic lymphadenopathy.

Endoluminal Obstruction by Tumor

Most carcinoid tumors are primarily endobronchial lesions, occurring in the central, main,

or segmental bronchi (Fig. 5). Some small tumors are located entirely within the lumen. How-

W160

AJR:193, September 2009

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Bronchiectasis

Fig. 5Carcinoid. This predominantly endobronchial tumor, arising before bifurcation of left upper and lower

lobe bronchi, causes distal bronchiectasis.

A and B, Transverse images of tumor (arrow, A) and distal bronchiectasis (arrows, B).

C and D, Coronal oblique image (C) and volume-rendering reformation (D) in similar orientation as A and B show

central carcinoid tumor (arrows) and distal bronchiectasis (arrowheads, C).

ever, some display a dominant extraluminal component with only a small part of the tumor

lying within the airway (iceberg lesion). A variety of other benign and malignant neoplasms

can also result in obstruction leading to focal bronchiectasis.

Foreign Body

Aspirated foreign material can result in focal bronchiectasis. Persistence of a noncalcified

foreign body, such as a vegetable fiber, within a bronchus for a prolonged period of time can

serve as a nidus for calcium deposition.

Broncholithiasis

Calcified or ossified material within the bronchial lumen can cause focal bronchiectasis.

By far the most common cause of broncholithiasis is erosion by and extrusion of a calcified

AJR:193, September 2009

W161

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Cantin et al.

Fig. 6Broncholithiasis.

AC, Calcified left upper lobe endobronchial

broncholithiasis (arrow) from previous tuberculosis

exposure is seen on transverse image (A), minimumintensity-projection reformation in coronal oblique

plane (B), and volume-rendering reformation (C)

in similar orientation. In C, arrow points to distal

bronchiectasis.

C

adjacent lymph node, usually associated with a long-standing focus of necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenitis, especially after tuberculosis (Fig. 6). Nevertheless, the frequency of

broncholithiasis complicating granulomatous infection is quite low. The most common sites

are the proximal right middle lobe bronchus and the origin of the anterior segmental bronchus

of the upper lobes because of airway anatomy and lymph node distribution.

Airway Stenosis

Airway stenosis causing focal bronchiectasis (Fig. 7) can result from a broad spectrum of

entities including infection, intubation stricture, healing of a tracheostomy stoma, tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica, amyloidosis, relapsing polychondritis, sarcoidosis, and

fibrosing mediastinitis.

Diffuse Bronchiectasis: Upper Predominance

Cystic Fibrosis

The most common cause of congenital upper-lung-predominant bronchiectasis is cystic

fibrosis, commonly associated with enlarged lung volumes and interstitial alterations (Fig. 8).

An autosomal recessive genetic disorder causing ineffective clearance of secretions, cystic

fibrosis presents with recurrent pneumonias, sinusitis, pancreatic insufficiency, and infertility.

Milder forms of cystic fibrosis, however, can remain unrecognized until adulthood (Fig. 9).

W162

AJR:193, September 2009

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Bronchiectasis

C

Fig. 7Congenital stenosis of left mainstem bronchus.

A and B, Transverse images show stenosis (arrow, A), distal bronchiectasis, and mucoid impaction (arrows, B).

C, Coronal reformation image shows bronchial stenosis (arrow).

Sarcoidosis

Parenchymal involvement by sarcoidosis can lead to upper and mid lung fibrosis and traction bronchiectasis, typically associated with multiple nodules in a perilymphatic distribution

(Fig. 10). Mediastinal and bilateral symmetric lymphadenopathy is common, although it can

regress as the interstitial disease worsens.

Postradiation Fibrosis

Another important cause of upper-lung-predominant bronchiectasis is postradiation fibrosis, in which traction bronchiectasis is usually limited to the radiation port (Fig. 11). A straight

interface between the irradiated field and normal lung is often seen. This does not respect

anatomic borders, such as fissures and lobes. Postradiation fibrosis may also be bilateral after

mediastinal radiation for lymphoma.

AJR:193, September 2009

W163

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Cantin et al.

A

Fig. 8Cystic fibrosis.

A and B, Transverse (A) and coronal (B) images show

upper lobe predominance of cystic bronchiectasis

(arrows) and volume loss, enlarged lung volumes, and

diffuse heterogeneous attenuation.

Fig. 9Adult cystic fibrosis. In this milder case, there is upper lobe predominance of cylindric bronchiectasis

(white arrows) and bronchiolitis (black arrows).

W164

AJR:193, September 2009

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Bronchiectasis

B

Fig. 10Sarcoidosis.

A and B, Transverse images show fibrosis and traction bronchiectasis (arrows, B) that predominantly involve

upper lobes.

Diffuse Bronchiectasis: Lower Predominance

Lower-lung-predominant bronchiectasis, which is the most frequent pattern, is most commonly idiopathic (Fig. 12). However, some cases have known causes.

Recurrent Childhood Infections

Postinfectious bronchiectasis is a frequent cause of lower-lung-predominant bronchiectasis. It is less seen today because of better control of tuberculosis, earlier treatment of pneumonia, and immunization. However, recurrent infections still remain a frequent cause of bronchiectasis in immune-suppressed patients.

Aspiration

Any predisposition for repeated aspiration is associated with an increased risk of developing bibasilar bronchiectasis. Common causes include a large hiatal hernia with gastroesophageal reflux, scleroderma (Fig. 13) and other causes of a patulous esophagus, and esophageal

motility disorders.

AJR:193, September 2009

W165

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Cantin et al.

Fig. 11Postradiation fibrosis.

A and B, Right paramediastinal fibrotic changes, which developed after treatment of lung cancer, are

associated with traction bronchiectasis (arrows).

Fig. 12Lower lobe predominance of bronchiectasis.

A, Subtle idiopathic bibasilar cylindric bronchiectasis

shows signet-ring sign (arrows).

B, In another patient, there is marked idiopathic left

lower bronchiectasis with volume loss, bronchial wall

thickening, and diffuse opacity.

Fibrotic Lung Disease

Bronchiectasis predominantly involving lung bases is a common finding in fibrotic lung

disease. In usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), coarse reticulation, honeycombing, parenchymal distortion, and traction bronchiectasis are typically predominant in a subpleural and

W166

AJR:193, September 2009

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Bronchiectasis

Fig. 13Scleroderma. There is patulous esophagus (white arrow), recurrent aspiration with subsequent

bibasilar bronchiectasis, and chronic ground-glass opacities. Black arrow points to bronchus visible in

peripheral 1 cm of lung.

Fig. 14Usual interstitial pneumonia. Bibasilar and subpleural reticulation and traction bronchiectasis are

seen in areas of fibrosis (arrows).

bibasilar distribution with geographic heterogeneity (Fig. 14). Although often idiopathic, UIP

occurs in asbestosis, drug toxicity, and collagenvascular disease. Nonspecific interstitial

pneumonia has almost the same differential diagnosis but typically occurs in younger patients

and carries a better prognosis. Ground-glass opacity is more frequent than in UIP and honeycombing usually remains minimal.

Rare Causes

Bronchiolitis obliterans from posttransplantation rejection is a rare cause of bronchiectasis

associated with patchy mosaic perfusion, air trapping, and bronchiolar obstruction (Fig. 15).

Hypogammaglobulinemia can also be a cause of lower-lung-predominant bronchiectasis,

most often caused by recurrent infections.

AJR:193, September 2009

W167

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Cantin et al.

Fig. 15Bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplantation.

A and B, Transverse images of right lung in deep inspiration (A) and end expiration (B) show subtle basilar

cylindric bronchiectasis (arrows, A) and widespread air trapping (arrows, B).

Fig. 16Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection. Bronchiectasis (arrows) predominantly involves right

middle lobe and lingula.

Diffuse Bronchiectasis: Middle Lobe and Lingula Predominance

Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infection

The most common acquired cause of bronchiectasis predominantly involving the right

middle lobe and lingula is nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, such as Mycobacterium

avium-intracellulare (MAI). This infection, typically seen in women over 60 years old, presents with chronic infection, bronchiectasis, mucoid impaction, and bronchiolitis (Fig. 16).

The disease often has an indolent but progressive course requiring long-term antibiotics.

Immobile Cilia Syndrome

This rare congenital cause of bronchiectasis, which primarily involves the middle lung, is

characterized by ineffective clearing of secretions, causing bronchiectasis, recurrent pneumonias, sinusitis, and infertility. In 50% of cases, total situs inversus is present, a condition

known as Kartageners syndrome (Fig. 17).

W168

AJR:193, September 2009

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Bronchiectasis

Fig. 17Kartageners syndrome.

A, Chest radiograph shows cardiomegaly, dextrocardia, left middle lobe bronchiectasis, and volume loss.

Arrow points to wrong-sided left marker.

B, Transverse CT image confirms dextrocardia (asterisk is in left ventricle) and bronchiectasis (arrows) that

predominantly affects midportion of lungs.

Fig. 18Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

A, Chest radiograph shows central bronchiectasis

and mucoid impaction, so-called finger-in-glove

appearance (arrows).

B, Transverse CT image shows central

bronchiectasis, mucoid impaction (large arrow), and

distal bronchiolitis (small arrow).

B

AJR:193, September 2009

W169

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Cantin et al.

B

Fig. 19Mounier-Kuhns syndrome.

A, Enlarged trachea (arrow).

B, Enlarged mainstem bronchi (black arrows) and distal bronchiectasis (white arrows).

Fig. 20Williams-Campbell syndrome. There is mostly varicose and cystic central bronchiectasis (arrows).

W170

AJR:193, September 2009

Bronchiectasis

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 36.81.19.190 on 11/22/14 from IP address 36.81.19.190. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Diffuse Bronchiectasis: Central Predominance

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is an immune reaction to Aspergillus species that

damages the bronchial wall, causing central bronchiectasis and mucous plugs that contain

fungus and inflammatory cells. On chest radiography, this produces a characteristic finger-inglove appearance. On CT, central bronchiectasis and mucoid impactions are often associated

with areas of peripheral bronchiolitis, manifesting as bronchiolar nodules or tree-in-bud

opacities (Fig. 18).

Cartilage-Deficiency Disorders

Several rare disorders characterized by cartilage deficiency can cause bronchiectasis that

primarily involves the central regions of the lung. One is tracheobronchomegaly, also known as

Mounier-Kuhns syndrome, which manifests as diffuse enlargement of the trachea and mainstem bronchi with more distal bronchiectasis (Fig. 19).

An even rarer cartilage deficiency disorder is the Williams-Campbell syndrome, in which

central bronchiectasis, mimicking the appearance of parenchymal cysts, is associated with

widespread air trapping (Fig. 20).

Suggested Reading

1. Barker AF. Bronchiectasis. New Engl J Med 2002; 346:13831393

2. Baydarian M, Walter RN. Bronchiectasis: introduction, etiology, and clinical features. Dis Mon 2008;

54:516526

3. Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon TC, McLoud TC, Mller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary

of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008; 246:697722

4. Javidan-Nejad C, Bhalla S. Bronchiectasis. Radiol Clin North Am 2009; 47:289306

5. Kim JS, Mller NL, Park CS, Grenier P, Herold CJ. Cylindrical bronchiectasis: diagnostic findings on thinsection CT. AJR 1997; 168:751754

6. ODonnell AE. Bronchiectasis. Chest 2008; 134:815823

7. Quast TM, Self AR, Browning radiofrequency: diagnostic evaluation of bronchiectasis. Dis Mon 2008;

54:527539

8. Reid LM. Reduction in bronchial subdivision in bronchiectasis. Thorax 1950; 5:233247

AJR:193, September 2009

W171

Você também pode gostar

- Art:10.1007/s00247 005 1559 7 PDFDocumento12 páginasArt:10.1007/s00247 005 1559 7 PDFHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- Critical ThinkingDocumento2 páginasCritical ThinkingMwagaVumbiAinda não há avaliações

- Bronkiektasis PDFDocumento14 páginasBronkiektasis PDFHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- Neuro BlastomaDocumento7 páginasNeuro BlastomaHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- A Rare Cause of Reversible Unilateral Breast Swelling: A Case ReportDocumento3 páginasA Rare Cause of Reversible Unilateral Breast Swelling: A Case ReportHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- A Rare Cause of Reversible Unilateral Breast Swelling: A Case ReportDocumento3 páginasA Rare Cause of Reversible Unilateral Breast Swelling: A Case ReportHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- Review Article: Differentiating Between Hemorrhagic Infarct and Parenchymal Intracerebral HemorrhageDocumento12 páginasReview Article: Differentiating Between Hemorrhagic Infarct and Parenchymal Intracerebral HemorrhageHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- Journal Cystic Abdominal Masses PDFDocumento16 páginasJournal Cystic Abdominal Masses PDFHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- Review Article: Differentiating Between Hemorrhagic Infarct and Parenchymal Intracerebral HemorrhageDocumento12 páginasReview Article: Differentiating Between Hemorrhagic Infarct and Parenchymal Intracerebral HemorrhageFika Tri NandaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal PneumoniaDocumento12 páginasJurnal PneumoniaHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- Journal Cystic Abdominal MassesDocumento16 páginasJournal Cystic Abdominal MassesHalida Batik AlunaAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Strategies For StartupDocumento16 páginasStrategies For StartupRoshankumar BalasubramanianAinda não há avaliações

- Shopping Mall: Computer Application - IiiDocumento15 páginasShopping Mall: Computer Application - IiiShadowdare VirkAinda não há avaliações

- Paper 4 (A) (I) IGCSE Biology (Time - 30 Mins)Documento12 páginasPaper 4 (A) (I) IGCSE Biology (Time - 30 Mins)Hisham AlEnaiziAinda não há avaliações

- Oxgen Sensor Cat WEBDocumento184 páginasOxgen Sensor Cat WEBBuddy Davis100% (2)

- WWW - Commonsensemedia - OrgDocumento3 páginasWWW - Commonsensemedia - Orgkbeik001Ainda não há avaliações

- Copula and Multivariate Dependencies: Eric MarsdenDocumento48 páginasCopula and Multivariate Dependencies: Eric MarsdenJeampierr Jiménez CheroAinda não há avaliações

- Cableado de TermocuplasDocumento3 páginasCableado de TermocuplasRUBEN DARIO BUCHELLYAinda não há avaliações

- Fast Aldol-Tishchenko ReactionDocumento5 páginasFast Aldol-Tishchenko ReactionRSLAinda não há avaliações

- The Smith Generator BlueprintsDocumento36 páginasThe Smith Generator BlueprintsZoran AleksicAinda não há avaliações

- United-nations-Organization-uno Solved MCQs (Set-4)Documento8 páginasUnited-nations-Organization-uno Solved MCQs (Set-4)SãñÂt SûRÿá MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Essential Rendering BookDocumento314 páginasEssential Rendering BookHelton OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- 202112fuji ViDocumento2 páginas202112fuji ViAnh CaoAinda não há avaliações

- Joining Instruction 4 Years 22 23Documento11 páginasJoining Instruction 4 Years 22 23Salmini ShamteAinda não há avaliações

- Arta Kelmendi's resume highlighting education and work experienceDocumento2 páginasArta Kelmendi's resume highlighting education and work experienceArta KelmendiAinda não há avaliações

- Analyze and Design Sewer and Stormwater Systems with SewerGEMSDocumento18 páginasAnalyze and Design Sewer and Stormwater Systems with SewerGEMSBoni ClydeAinda não há avaliações

- Process Financial Transactions and Extract Interim Reports - 025735Documento37 páginasProcess Financial Transactions and Extract Interim Reports - 025735l2557206Ainda não há avaliações

- Why Choose Medicine As A CareerDocumento25 páginasWhy Choose Medicine As A CareerVinod KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Allan S. Cu v. Small Business Guarantee and FinanceDocumento2 páginasAllan S. Cu v. Small Business Guarantee and FinanceFrancis Coronel Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Form 709 United States Gift Tax ReturnDocumento5 páginasForm 709 United States Gift Tax ReturnBogdan PraščevićAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial 1 Discussion Document - Batch 03Documento4 páginasTutorial 1 Discussion Document - Batch 03Anindya CostaAinda não há avaliações

- SEC QPP Coop TrainingDocumento62 páginasSEC QPP Coop TrainingAbdalelah BagajateAinda não há avaliações

- (123doc) - Chapter-24Documento6 páginas(123doc) - Chapter-24Pháp NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Typical T Intersection On Rural Local Road With Left Turn LanesDocumento1 páginaTypical T Intersection On Rural Local Road With Left Turn Lanesahmed.almakawyAinda não há avaliações

- Reading Comprehension Exercise, May 3rdDocumento3 páginasReading Comprehension Exercise, May 3rdPalupi Salwa BerliantiAinda não há avaliações

- Srimanta Sankaradeva Universityof Health SciencesDocumento3 páginasSrimanta Sankaradeva Universityof Health SciencesTemple RunAinda não há avaliações

- Link Ratio MethodDocumento18 páginasLink Ratio MethodLuis ChioAinda não há avaliações

- Dance Appreciation and CompositionDocumento1 páginaDance Appreciation and CompositionFretz Ael100% (1)

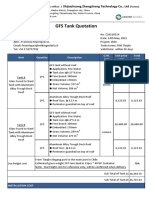

- GFS Tank Quotation C20210514Documento4 páginasGFS Tank Quotation C20210514Francisco ManriquezAinda não há avaliações

- Key Fact Sheet (HBL FreedomAccount) - July 2019 PDFDocumento1 páginaKey Fact Sheet (HBL FreedomAccount) - July 2019 PDFBaD cHaUhDrYAinda não há avaliações

- Build A Program Remote Control IR Transmitter Using HT6221Documento2 páginasBuild A Program Remote Control IR Transmitter Using HT6221rudraAinda não há avaliações