Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

African Elephants Show

Enviado por

Alfonso FajardoDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

African Elephants Show

Enviado por

Alfonso FajardoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.

org/ on September 1, 2015

on encountering the bodies of dead con-specifics,

becoming highly agitated and investigating them with

the trunk and feet, but also to pay considerable

attention to the skulls, ivory and associated bones of

elephants that are long dead (Douglas-Hamilton &

Douglas-Hamilton 1975; Moss 1988; Spinage 1994).

It has also been suggested that elephants specifically

visit the bones of dead relatives (Douglas-Hamilton &

Douglas-Hamilton 1975; Moss 1988; Spinage 1994).

Despite being widely reported, there have been no

attempts to elicit and investigate these unusual behaviours experimentally. Apparent interest in skulls and

ivory may simply reflect a strong response to novel

objects or a fidelity to certain routes, and the nature

and specificity of elephant responses to the remains of

other elephants can only be unambiguously determined using controlled experiments. Here, we use

experimental presentations of object arrays to test

whether elephants are indeed specifically attracted to

the skulls and ivory of other elephants, and whether

they show particular interest in these remains when

they originate from their relatives.

Biol. Lett. (2006) 2, 2628

doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0400

Published online 25 October 2005

African elephants show

high levels of interest in

the skulls and ivory of their

own species

Karen McComb1,*, Lucy Baker1

and Cynthia Moss2

1

School of Life Sciences, University of Sussex, Brighton BN1 9QG, UK

Amboseli Trust for Elephants, PO Box 15135, Langata 00509,

Nairobi, Kenya

*Author for correspondence (karenm@biols.susx.ac.uk).

2

An important area of biology involves investigating the origins in animals of traits that are

thought of as uniquely human. One way that

humans appear unique is in the importance they

attach to the dead bodies of other humans,

particularly those of their close kin, and the

rituals that they have developed for burying

them. In contrast, most animals appear to show

only limited interest in the carcasses or associated remains of dead individuals of their own

species. African elephants (Loxodonta africana)

are unusual in that they not only give dramatic

reactions to the dead bodies of other elephants,

but are also reported to systematically investigate elephant bones and tusks that they encounter, and it has sometimes been suggested that

they visit the bones of relatives. Here, we use

systematic presentations of object arrays to

demonstrate that African elephants show higher

levels of interest in elephant skulls and ivory

than in natural objects or the skulls of other

large terrestrial mammals. However, they do

not appear to specifically select the skulls of

their own relatives for investigation so that visits

to dead relatives probably result from a more

general attraction to elephant remains.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

(a) Study population

The research was conducted in Amboseli National Park, Kenya,

where long-term data on life histories have been obtained for more

than 2200 individual elephants (see McComb et al. 2001). The

primary social unit in African elephants is the female family unit,

composed of adult females that are usually matrilineal relatives and

their immature offspring (Moss & Poole 1983).

(b) Procedure for presentations

Between July 1998 and January, 2000, free-ranging African

elephants in the study population were presented with animal

skulls, ivory and natural objects to investigate: (i) whether they are

attracted to elephant skulls and ivory over other objects; (ii)

whether they show more interest in elephant skulls than in skulls of

other large terrestrial mammals; and (iii) whether they particularly

select the skulls of relatives for investigation. Controlled choice

tests were achieved by presenting family units with arrays of three

objects in which the location of each item in line (left, centre, right

with respect to the approaching elephants) was systematically varied

between trials to randomize the effects of preferences for particular

positions (see figure 1a and see electronic supplementary material).

For each presentation a suitable family unit (or section of a

family unit) was identified and a set of three objects (details of

different choice sets below) was decanted from the research vehicle

and placed at a distance of 2530 m from the nearest individual in

the family group. The three objects were placed in a line on the

ground with 1 m separating the central object from each of its

neighbours. The vehicle was then driven to a position where the

trial could be observed and video-recorded.

In the first experiment an elephant skull, a piece of ivory and a

piece of wood were presented to 19 different family groups

(figure 1a), while in the second, 17 family groups were presented

with an elephant skull, a buffalo skull and a rhinoceros skull (see

electronic supplementary material). In the third experiment, each

of three families that had lost their matriarch in the recent past (last

15 years) were presented with the choice between the skull of their

own matriarch and those of the matriarchs of the other two

families. All three families chose between the same three skulls,

with the skull that represented the matriarch for any one family

representing a non-matriarch for the other two, and each family

received the choice three times, with their own matriarchs skull in

each of the three possible positions in the array (see electronic

supplementary material). The matriarch is the oldest female in the

family unit, and plays an important role in coordinating the groups

activities (McComb et al. 2001).

In the first two experiments, two different exemplars of each

of the objects were used in the course of the presentations, while

in experiment 3, the three objects were skulls from previous

matriarchs of the JA/YA family (Jezebel), the TA family (Tuskless)

and the AA family (Wartear), who had all died between 1 and

5 years before their skulls were used in choice tests. At least one

week was left between different presentations to the same family.

All the skulls used in the experiments were completely rotted down,

Keywords: elephants; skulls; ivory; bones; death

1. INTRODUCTION

In contrast to humans, who attach great importance to

the dead bodies of other humans (Tattersall 1998),

most mammals show only passing interest in the dead

remains of their own or other species. Lions are typical

in this respect, briefly sniffing or licking the dead body

of a con-specific which, in the case of recently killed

individuals, may subsequently be eaten (Schaller

1972; Packer, C. R., personal communication). In

chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), interactions with dead

social partners are more prolonged and complex than

reported in other species, but here companions tend to

leave the carcass when it starts to decompose significantly, and do not appear to interact with the bones

once the carcass has rotted (Boesch & BoeschAchermann 2000). In comparison, African elephants

are reported not only to exhibit unusual behaviours

The electronic supplementary material is available at http://dx.doi.

org/10.1098/rsbl.2005.0400 or via http://www.journals.royalsoc.

ac.uk.

Received 13 June 2005

Accepted 21 September 2005

26

q 2005 The Royal Society

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on September 1, 2015

Elephant interest in skulls and ivory

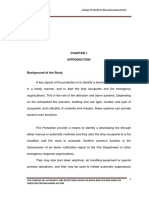

(a)

K. McComb and others 27

(b) 400

ivory

elephant skull

wood

high interest activity (s)

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

Experiment 1

(c) 60

elephant

buffalo

rhino

40

30

20

10

matriarch

non-matriarch

120

high interest activity (s)

high interest activity (s)

50

(d) 140

100

80

60

40

20

0

0

Experiment 2

Experiment 3

Figure 1. (a) Choice test on array of wood, elephant skull and ivory (left to right) in experiment 1. In this photo, one family

member initiates approach to the object array (to be followed by others from right of frame). (b) Distribution of high interest

activity in experiment 1, bars show standard errors. (c) Distribution of high interest activity in experiment 2, bars show

standard errors. (d ) Distribution

of high interest activity in experiment

3, bars show pooled standard errors from the three

p

families, where s:e: pooledZ s:e: fam:21 C s:e: fam:22 C s:e: fam:23 =3:

so that there was no remaining flesh and the bone was bleached

white by the sun. All items were washed with a solution of Teepol

(which has a low number of contaminant volatiles), given two

thorough rinses and air dried before and after experiments. This

both controlled for any extraneous differences in scent between the

objects prior to the experiments, and prevented accumulation of

scent (from handling or elephant interest in particular objects)

during the experiments.

(c) Behavioural responses

The elephants typically approached the objects and began

investigating them by smelling and touching individual objects

with their trunks and, more rarely, placing their feet lightly

against particular objects and manipulating them (similar behaviours are observed during natural encounters with elephant

remains, e.g. Spinage 1994). The responses of subjects to each

presentation were recorded using a Sony CCD TR550E video

recorder. Trials were terminated when all the individuals had

finished investigating the objects and moved on, or if an

individual carried an object four or more elephant lengths away

from the other items. From video-recordings of their responses,

we calculated the cumulative amount of time that adult group

members (11 years or older) spent smelling towards an object

with the trunk tip less than 1 m from it, or touching the object

with the trunk (high interest activity). In addition, in the case of

trials involving ivory, where placing of the foot on top of objects

occurred fairly regularly, the cumulative time spent by any adult

touching an item with its foot was also calculated (Foot on

object). Elephants have mechanoreceptors in their feet, and foot

Biol. Lett. (2006)

placement on objects may enable them to gather tactile information (OConnell-Rodwell et al. 2000)

3. RESULTS

Subjects directed significantly different amounts of

high interest activity towards the three objects in the

first experiment, exhibiting a strong preference for

ivory over each of the other two objects and for the

elephant skull over wood (figure 1b; Friedman test

NZ19, c2Z22.81, d.f.Z2, pZ!0.001; Wilcoxon

Signed Ranks Test for ivory versus elephant skull:

ZZ3.58; p!0.001, for ivory versus wood: ZZ3.70;

p!0.001, and for elephant skull versus wood ZZ3.29;

p!0.005.). In the second experiment, interest in the

three types of animal skull also differed, subjects

exhibiting more interest in the elephant skull than in

the buffalo or rhino skulls, but not in the buffalo skull

compared with the rhino skull (figure 1c; Friedman

Test NZ17, c2Z7.12, d.f.Z2, pZ!0.05; Wilcoxon

Signed Ranks Test for elephant versus buffalo skull:

ZZ2.27; p!0.05, for elephant versus rhino skull:

ZZ2.56; pZ0.01, and for buffalo skull versus rhino

skull ZZ0.25; n.s.). In the final experiment, subjects

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on September 1, 2015

28

K. McComb and others Elephant interest in skulls and ivory

did not direct significantly more high interest activity

towards the skull of their own matriarch than towards

the skulls of the two other matriarchs (figure 1d;

Binomial test on number of trials where skull that

received the most attention was own matriarchs skull:

NZ9, kZ4, pZ0.35). Due to constraints on the

sample size, this experiment would be effective in

demonstrating a strong preference for the correct

matriarchs skull (for probabilities of success under the

alternative hypothesis of 0.7, 0.8 and 0.9, power of

tests would be 0.730, 0.914 and 0.992, respectively),

but not a weak one (for probabilities of success under

the alternative hypothesis of 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, power of

tests would be 0.099, 0.254 and 0.483, respectively).

Where touching of objects with the foot was

measured (experiment 1see 2) subjects spent

significantly more time with the foot placed on ivory

than on the elephant skull or wood, but not on

the elephant skull than on wood (Foot on object:

Friedman Test NZ19, c2Z9.864, d.f.Z2, pZ!0.01;

Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test for ivory versus elephant

skull: ZZ2.511; p!0.05, for ivory versus wood:

ZZ2.761; p!0.01 and for elephant skull versus wood

ZZ0.943; n.s.).

4. DISCUSSION

Our experiments cast light on why elephants are often

observed interacting with the skulls and ivory of dead

social companionsthey appear to choose these

items for investigation in preference to skulls from

other animals or natural objects. Their preference for

ivory was very marked, with ivory not only receiving

excessive attention in comparison with wood but also

being selected significantly more than the elephant

skull. Subjects also placed their feet on or against the

ivory significantly more often than on other objects.

Interest in ivory may be enhanced because of its

connection with living elephants, individuals sometimes touching the ivory of others with their trunks

during social behaviour. In experiments where no

ivory was present, other items in the array appeared

to receive less high interest activity overall. Despite

this, the elephant skull was clearly selected for

attention over the buffalo and rhinoceros skulls and

over the wood. It is important to note that our

findings cannot be explained by the elephants simply

choosing the largest, most complex objects (the object

that received the most attention overall was the ivory,

which is smallest in size and simplest in shape) or the

most novel ones (the rarest object was the rhinoceros

skull but this did not receive most attention).

Although there are suggestions in the literature that

elephants selectively visit the bones of their relatives

(Douglas-Hamilton & Douglas-Hamilton 1975; Moss

1988; Spinage 1994), our matriarch skulls presentations did not reveal a strong preference in experimental

subjects for investigating the skull of their matriarch

over skulls of unrelated females. While the sample size

for this experiment was unavoidably limited to nine

(three families presented with their matriarchs skull in

each of the three positions in the array), reducing the

power of the test, there was no evidence of the marked

Biol. Lett. (2006)

difference in interest in the three objects that was so

clear in the first two experiments.

Reports of elephant graveyards, specific places

where old elephants go to die, have been exposed as

mythswhere large concentrations of elephant bones

have been found their occurrence can be adequately

explained by hunting practices or mass die-offs during

periods of drought (Moss 1988; Spinage 1994). Our

results suggest that elephants may not specifically

select the skulls of their own relatives for investigation,

but their strong interest in the ivory and skulls of their

own species means that they would be highly likely to

visit the bones of relatives who die within their own

home range. This is the most likely explanation for

why elephants have sometimes been observed interacting with the bones of particular family members,

although it remains possible that where ivory is present

alongside skulls, elephants may, through tactile or

olfactory cues, recognize tusks from individuals that

they have been familiar with in life.

The evolutionary basis for exhibiting such intense

interest in the decomposed remains of con-specifics

in a non-human mammal remains unclear. While the

behaviours described here obviously differ fundamentally from the attention and ritual that surround death

in humans, they are unusual and noteworthy. Comparative research is now required to test systematically

whether any other species show similar responses and

what relationship, if any, they have to particular

cognitive abilities or aspects of social behaviour.

We are grateful to the Kenyan Office of the President and

Kenya Wildlife Services for permission to conduct the work

in Amboseli National Park, to Soila Sayialel, Katito Sayialel

and Norah Njiriana for assistance with fieldwork, to Barbie

Allen for logistic support, to Zoltan Dienes, David Reby and

Stuart Semple for comments, and Ray Hilborn and Sarah

Durant for statistical advice on the matriarchs experiment.

Boesch, C. & Boesch-Achermann, H. 2000 The chimpanzees

of the Tai forest: behavioural ecology and evolution, 1st edn.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Douglas-Hamilton, I. & Douglas-Hamilton, O. 1975 Among

the elephants. London: Collins & Harvill.

McComb, K., Moss, C., Durant, S., Baker, L. & Sayialel, S.

2001 Matriarchs act as repositories of social knowledge in

African elephants. Science 292, 491494.

Moss, C. 1988 Elephant memories: thirteen years in the life of

an elephant family, 1st edn. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins.

Moss, C. J. & Poole, J. H. 1983 Relationships and social

structure of African elephants. In Primate social relationships: an integrated approach (ed. R. A. Hinde),

pp. 315325. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific.

OConnell-Rodwell, C. E., Arnason, B. & Hart, L. A. 2000

Seismic properties of elephant vocalisations and locomotion. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 108, 30663072. (doi:10.

1121/1.1323460)

Schaller, G. B. 1972 The Serengeti lion: a study of predatorprey relations, 1st edn. Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

Spinage, C. A. 1994 Elephants. London: T & A D Poyser.

Tattersall, I. 1998 Becoming human: evolution and human

uniqueness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Tang2021 Article NonhumanPrimateMeso-circuitryDDocumento11 páginasTang2021 Article NonhumanPrimateMeso-circuitryDAlfonso FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- Resting State Networks in Temporal Lobe EpilepsyDocumento12 páginasResting State Networks in Temporal Lobe EpilepsyAlfonso FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- Rplot ExampleDocumento1 páginaRplot ExampleAlfonso FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- UnixDocumento249 páginasUnixAlfonso Fajardo100% (3)

- From Regions To Connections and Networks New Bridges Between Brain and BehaviorDocumento7 páginasFrom Regions To Connections and Networks New Bridges Between Brain and BehaviorAlfonso FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- Buxton, The Phisycs of Functional Resonance ImagingDocumento31 páginasBuxton, The Phisycs of Functional Resonance ImagingAlfonso FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- Impulsive Choice Induced in Rats by Lesions of The Nucleus Accumbens CoreDocumento4 páginasImpulsive Choice Induced in Rats by Lesions of The Nucleus Accumbens CoreAlfonso FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- Accesare - Resursa 1Documento17 páginasAccesare - Resursa 1Flory FloricaAinda não há avaliações

- Monday Neuroscience ProgramDocumento183 páginasMonday Neuroscience ProgramAlfonso Fajardo0% (1)

- A Negative Relationship Between Ventral Striatal Loss Anticipation Response and Impulsivity in Borderline Personality DisorderDocumento36 páginasA Negative Relationship Between Ventral Striatal Loss Anticipation Response and Impulsivity in Borderline Personality DisorderAlfonso FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter05 Resward and PunishmentDocumento28 páginasChapter05 Resward and PunishmentAlfonso FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- PA 102 Human Behavior in OrganizationDocumento13 páginasPA 102 Human Behavior in OrganizationZheya SalvadorAinda não há avaliações

- Iran Zinc Mines Development Company: Industry Overview and R&D Center Research ActivitiesDocumento5 páginasIran Zinc Mines Development Company: Industry Overview and R&D Center Research ActivitiesminingnovaAinda não há avaliações

- Doisha Wulbareg Rainfal Frequency AnalysisDocumento64 páginasDoisha Wulbareg Rainfal Frequency AnalysisAbiued EjigueAinda não há avaliações

- The Social Dilemma of Autonomous VehiclesDocumento6 páginasThe Social Dilemma of Autonomous Vehiclesywan99Ainda não há avaliações

- Forging The Elements of A World-Class UniversityDocumento32 páginasForging The Elements of A World-Class UniversityUPLB Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and ExtensionAinda não há avaliações

- 8 1 Book Review 4Documento3 páginas8 1 Book Review 4TinoroAinda não há avaliações

- ER Diagram Case StudyDocumento4 páginasER Diagram Case StudyRishikesh MahajanAinda não há avaliações

- Module 7 ANOVAsDocumento44 páginasModule 7 ANOVAsJudyangaangan03Ainda não há avaliações

- StatisicsDocumento2 páginasStatisicsMary Joy Heraga PagadorAinda não há avaliações

- Pmi Salarysurvey 7th EditionDocumento295 páginasPmi Salarysurvey 7th EditionFernando MarinAinda não há avaliações

- Project Three: Simple Linear Regression and Multiple RegressionDocumento10 páginasProject Three: Simple Linear Regression and Multiple RegressionnellyAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review Strengths and LimitationsDocumento7 páginasLiterature Review Strengths and Limitationsafdtvdcwf100% (1)

- RIFTY VALLEY University Gada Campus Departement of AccountingDocumento9 páginasRIFTY VALLEY University Gada Campus Departement of Accountingdereje solomonAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation Topics On Sales ManagementDocumento5 páginasDissertation Topics On Sales ManagementProfessionalCollegePaperWritersMcAllen100% (1)

- WIPO Indicators 2012Documento198 páginasWIPO Indicators 2012Hemant GoyatAinda não há avaliações

- PNTC Colleges Q.C. College of Maritime Education DepartmentDocumento5 páginasPNTC Colleges Q.C. College of Maritime Education DepartmentMichelle RaquepoAinda não há avaliações

- Job StatisfactionDocumento425 páginasJob StatisfactionGuru MoorthyAinda não há avaliações

- The Learner Produces A Detailed Abstract of Information Gathered From The Various Academic Texts ReadDocumento6 páginasThe Learner Produces A Detailed Abstract of Information Gathered From The Various Academic Texts ReadRomy Sales Grande Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Reflection 1Documento6 páginasReflection 1api-177768681Ainda não há avaliações

- Prevalensi MalocclusionDocumento5 páginasPrevalensi MalocclusionIdelia GunawanAinda não há avaliações

- IJDIWC - Volume 4, Issue 3Documento144 páginasIJDIWC - Volume 4, Issue 3IJDIWCAinda não há avaliações

- Calabrese1999 PDFDocumento9 páginasCalabrese1999 PDFROSNANIAinda não há avaliações

- Essay Critical ThinkingDocumento8 páginasEssay Critical Thinkingafiboeolrhismk100% (2)

- Lesson 05 - Discrete Probability DistributionsDocumento61 páginasLesson 05 - Discrete Probability Distributionspuvitta sudeshilaAinda não há avaliações

- Report Geomatic (Levelling)Documento12 páginasReport Geomatic (Levelling)Lili Azizul100% (2)

- Applications of GIS in Water ResourcesDocumento19 páginasApplications of GIS in Water ResourcesBhargav YandrapalliAinda não há avaliações

- Astm E1268Documento28 páginasAstm E1268annayya.chandrashekar Civil EngineerAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 12 ReseachDocumento54 páginasGrade 12 Reseachjaiscey valenciaAinda não há avaliações

- Pmbok5 Project Management Process GroupsDocumento1 páginaPmbok5 Project Management Process GroupsGeethaAinda não há avaliações

- Mixed MethodsDocumento69 páginasMixed MethodsSajan KsAinda não há avaliações