Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Art Activism in Latin America - Reina Sofia

Enviado por

Renato David Bermúdez DiniDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Art Activism in Latin America - Reina Sofia

Enviado por

Renato David Bermúdez DiniDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Art Activism in Latin America

In the face of a longing for revolution, the string of military coup dtats throughout the 1960s and 1970s would

chart a new political and artistic map in Latin America. In 1973, the year of the coup dtat in Chile, led by

Augusto Pinochet, Juan Carlos Romero (1931) presented the installation Violencia (19731977), made up

of texts, images, newspaper headlines and posters. Romero would record the heat of a conflict that poured

through the streets, revealing the narrow gap between a word (violence) and its form in reality. Through his

designs of prisons for artists, Horacio Zabala (1943), in contrast, represented a form of silent, buried violence

that foretold the fate of thousands of people that went missing during the dictatorship.

The human body was also the subject of works with a political focus. El perchero (The Clothes Rack, 1975) by Carlos Leppe (19522015) featured three photographs, hung on a wooden coat rack, of

the artist dressed in womens clothing. Leppe crossed references

to the military order imposed on bodies by the dictatorship in Chile

(from torture to amputation, and even physical disappearance) with

impositions of gender associated with totalitarianism. In a line of

work akin to Leppes, the Chilean writer and visual artist Diamela

Eltit (1949) upheld the concrete substance of pain associated

with identity and materialised in a sacrificial, wounded, and above

all, marginal body. The artist read the content of her novel Lumprica (1983) inside a brothel, before kneeling down to clean the street

where it was located. These artists applied strategies that travel

across the intimate space of the lacerated body to public intervention in the city.

In these decades Brazil also experienced one of its toughest periods of military dictatorship, which lasted 21 years (19641985).

Artists such as Letcia Parente (1930), Anna Bella Geiger (1933)

and Cildo Meireles (1948) used their artistic practice as a guerrilla

instrument against the processes of internal political oppression, as

well as the cultural and economic colonialism of foreign action.

If in 1968 art was called upon to intervene in a radical chapter in history, during the 1970s, when dictatorship violence cancelled revolutionary demands, art took risks through other strategies of resistance in a gesture of reappropriation in the occupied and militarised

public sphere.

F.E. Solanas y O. Getino

La hora de los hornos, 1968

The radical questioning of art and its practices that took hold in the 1960s and 1970s was not limited to the

plastic arts, it was also happening in film. In the world of documentary, revolts and sociopolitical movements

gave rise to an ideological cinema the like of which had never previously existed. La hora de los hornos (The Hour

of the Furnaces, 1968) by Fernando Solanas (1936) and Octavio Getino (1935) made a very clear, fundamental contribution to the redefining of political cinema, and became a model for post-May 68 militant internatio-

Using a similar method to the Latin American artists shown in the previous room, and against the same background of major social upheaval and political crackdowns, Solanas and

Getino managed to produce, distribute and show their film using a variety of strategies to

get round General Juan Carlos Onganas dictatorial political repression in Argentina. They

built up a nationwide network of groups responsible for the clandestine distribution of the

film: popular organizations and workers and students groups. Projection was controlled by

a narrator who would stop the film every time anybody wanted to debate a point or suggest

ideas for the revolutionary struggle. Internationally, it was shown at events including the

Pesaro International Film Festival of New Cinema and the Cannes Film Festival.

Bibliography

Paniagua, Paulo Antonio (ed.): Cine

documental en Amrica Latina.

Madrid: Ctedra, 2003.

Solanas, F. E. y Getino, O.: Cine,

cultura y descolonizacin. Mxico:

Siglo XXI, 1973.

Links

http://www.cinelatinoamericano.cult.cu/biblioteca/fondo.

aspx?cod=2408

http://www.pinosolanas.com/

la_hora_info.htm

NIPO 036-14-019-5

The film is divided into three parts: Neocolonialism and Violence, Act for Liberation and Violence and Liberation. The first is being shown in this room because it is the most innovative

and experimental in terms of its use of film language. With its 88 minute duration and organization into thirteen film essays analyzing Argentine and Latin American history from

outside the official perspective, the film is constructed like a collage with images taken

from the press and documentary films like Fernando Birris Tire di and Humberto Ros

Faena, quotes from Frantz Fanon, Juan D. Pern and Ernesto Che Guevara (to whom the

film is largely dedicated) and snatches of music that reinforce the idea of calling people to

violence, such as the insistent African drums. All this builds into an emotionally powerful

film with one very clear objective: to show and to change the reality of the people of Latin America. So the film becomes a theoretical-practical experience, and it was precisely

because of making the film that the authors decided to create the Cine Liberacin group,

which produced the manifesto-document Hacia un Tercer Cine (Towards a Third Cinema,

1969) setting out the ideological and aesthetic bases of their acts. The group saw the projector as a weapon firing twenty-four frames a second, a weapon whose target was the

passive spectator - a coward and traitor in Fanons words to goad him onto joining the

revolutionary activity.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Michael Baxandall Painting and Experience in Fifteenthcentury Italy A Primer in The Social History of Pictorial Style 1Documento97 páginasMichael Baxandall Painting and Experience in Fifteenthcentury Italy A Primer in The Social History of Pictorial Style 1Ja Vi0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Marker Motion Sineflex 97 ScoreDocumento5 páginasMarker Motion Sineflex 97 ScoreJUSTIN THOMASAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Public Art - IMMADocumento15 páginasWhat Is Public Art - IMMARenato David Bermúdez Dini100% (1)

- The ZX Spectrum Book - 1982 To 199xDocumento260 páginasThe ZX Spectrum Book - 1982 To 199xMattyLCFC100% (1)

- The Returned Playable Race and Backgrounds For TherosDocumento6 páginasThe Returned Playable Race and Backgrounds For TherosBillthe SomethingAinda não há avaliações

- Creativity Neuroscience Digital Installation Art - Allison ProcacciDocumento4 páginasCreativity Neuroscience Digital Installation Art - Allison ProcacciToni SimóAinda não há avaliações

- The Social Brain Hypothesis - Robin DunbarDocumento13 páginasThe Social Brain Hypothesis - Robin DunbarSuman Ganguli0% (1)

- The Art of Ancient EgyptDocumento10 páginasThe Art of Ancient EgyptRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Copyright & Plagiarism Guide for StudentsDocumento7 páginasCopyright & Plagiarism Guide for StudentsRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Sejten - Revisiting Duchamp FountainDocumento9 páginasSejten - Revisiting Duchamp FountainRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Public DomainDocumento30 páginasPublic DomainRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Visual Art and Political Thought in a Global AgeDocumento21 páginasVisual Art and Political Thought in a Global AgeBrígida CampbellAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding VisualityDocumento20 páginasUnderstanding VisualityRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- ARTMAKING IN AN AGE OF VISUAL CULTURE VISION AND VISUALITY Sydney Walker The Ohio State UniversityDocumento21 páginasARTMAKING IN AN AGE OF VISUAL CULTURE VISION AND VISUALITY Sydney Walker The Ohio State Universityksammy83Ainda não há avaliações

- Arte Util - Tucumán ArdeDocumento1 páginaArte Util - Tucumán ArdeRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Curating in Depth ToolkitDocumento66 páginasCurating in Depth ToolkitRenato David Bermúdez Dini100% (1)

- Egea - El Desencanto La Mirada Del PadreDocumento14 páginasEgea - El Desencanto La Mirada Del PadreRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

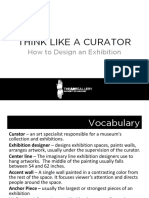

- Think Like A CuratorDocumento16 páginasThink Like A CuratorRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Enwezor Okwui 1999 Where What Who When A Few Notes On African Conceptualism PDFDocumento10 páginasEnwezor Okwui 1999 Where What Who When A Few Notes On African Conceptualism PDFRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Dunbar - The Social Brain Hypothesis and Its Implications For SocialDocumento12 páginasDunbar - The Social Brain Hypothesis and Its Implications For SocialRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Turner, Bryan S. - The End(s) of HumanityDocumento26 páginasTurner, Bryan S. - The End(s) of HumanityracorderovAinda não há avaliações

- What Is InstallationbookletDocumento15 páginasWhat Is InstallationbookletYocondo RiveraAinda não há avaliações

- Negotiating The Visual Turn PDFDocumento23 páginasNegotiating The Visual Turn PDFraúl rodríguez freireAinda não há avaliações

- Body ArtDocumento25 páginasBody ArtRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Richard Dawkins - Extended PhenotypeDocumento20 páginasRichard Dawkins - Extended Phenotypeanon-62127850% (2)

- Installation-About This Term - MoMADocumento5 páginasInstallation-About This Term - MoMARenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- The Interventionists PDFDocumento13 páginasThe Interventionists PDFRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Candice Brietz - White - Cube - CatalogueDocumento21 páginasCandice Brietz - White - Cube - CatalogueRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- What Is InstallationbookletDocumento15 páginasWhat Is InstallationbookletYocondo RiveraAinda não há avaliações

- SMITH, Terry-Contemporary Art World Currents... - 2012 PDFDocumento18 páginasSMITH, Terry-Contemporary Art World Currents... - 2012 PDFRenato David Bermúdez Dini100% (1)

- About First Papers of SurrealismDocumento10 páginasAbout First Papers of SurrealismRenato David Bermúdez DiniAinda não há avaliações

- Illusion and Art - E. H. GombrichDocumento25 páginasIllusion and Art - E. H. GombrichRenato David Bermúdez Dini0% (1)

- Compare and CotrastDocumento1 páginaCompare and CotrastJoanna ManaloAinda não há avaliações

- Ableton Live 8 Keyboard Shortcuts MacDocumento2 páginasAbleton Live 8 Keyboard Shortcuts MacPhil B ArbonAinda não há avaliações

- Each) : Grammar 1 Write The Question For Each Following Answer. Example: She Played Basketball YesterdayDocumento17 páginasEach) : Grammar 1 Write The Question For Each Following Answer. Example: She Played Basketball YesterdayProduction PeachyAinda não há avaliações

- A Pinhole Camera Has No Lens.Documento1 páginaA Pinhole Camera Has No Lens.M. Amaan AamirAinda não há avaliações

- Pierson's 8-Week Strength and Hypertrophy ProgramDocumento11 páginasPierson's 8-Week Strength and Hypertrophy ProgramHariprasaadAinda não há avaliações

- PortugalDocumento11 páginasPortugalLeila Vidallon Cuarteros100% (2)

- Sycamore Valley Ranch BrochureDocumento14 páginasSycamore Valley Ranch BrochureMiki ParkAinda não há avaliações

- LatestlogDocumento92 páginasLatestlogmasd17185Ainda não há avaliações

- Falkenbach - Ultima ThuleDocumento3 páginasFalkenbach - Ultima ThuleKronos TattooAinda não há avaliações

- OLYMPIC LIFTING EXERCISESDocumento23 páginasOLYMPIC LIFTING EXERCISESmrgrizzAinda não há avaliações

- Aef4 File 2 WordlistDocumento8 páginasAef4 File 2 WordlistYahya Al-AmeriAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan - AdjectiveDocumento8 páginasLesson Plan - AdjectiveBenediktus R. RattuAinda não há avaliações

- Billy Idol - Eyes Without A Face (Official Music Video) - Cambridge UniversityDocumento3 páginasBilly Idol - Eyes Without A Face (Official Music Video) - Cambridge UniversityAndres Camilo AcuñaAinda não há avaliações

- North AmericanDocumento16 páginasNorth AmericanKeneth CandidoAinda não há avaliações

- RetroArch Overlay GuideDocumento3 páginasRetroArch Overlay Guidebigwig001Ainda não há avaliações

- 30 Ratatouille - Passive VoiceDocumento1 página30 Ratatouille - Passive Voicecarlota mas de xaxasAinda não há avaliações

- Necromunda - Chart of ChartsDocumento5 páginasNecromunda - Chart of ChartscockybestgirlAinda não há avaliações

- Mechanical Puller Catalog - EU PDFDocumento20 páginasMechanical Puller Catalog - EU PDFAlvaroAinda não há avaliações

- Configuring NMX Server RedundancyDocumento22 páginasConfiguring NMX Server RedundancyRobertAinda não há avaliações

- Appnote VoceraDocumento4 páginasAppnote Vocerajcy1978Ainda não há avaliações

- Morales, Alisha Jana R. Tma 2 - Devc 206Documento7 páginasMorales, Alisha Jana R. Tma 2 - Devc 206Sam ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- EB - Lecture 2 - ECommerce Revenue Models - HDocumento8 páginasEB - Lecture 2 - ECommerce Revenue Models - HXolani MpilaAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher's Resource CD-ROM. Editable Test End of Year. Challenge LevelDocumento6 páginasTeacher's Resource CD-ROM. Editable Test End of Year. Challenge LevelCoordinacion Académica100% (1)

- Bom Unit-3Documento89 páginasBom Unit-3Mr. animeweedAinda não há avaliações

- Classroom Routines SY 23-24Documento30 páginasClassroom Routines SY 23-24Ervin Aeron Cruz SantosAinda não há avaliações

- Martial Arts in Runequest - House RuleDocumento4 páginasMartial Arts in Runequest - House RuleEric Wirsing100% (1)

- Module Two Wellness Plan ResultsDocumento13 páginasModule Two Wellness Plan ResultsJames Verdugo CalleAinda não há avaliações