Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Knowledge and Disclosure of Hiv Status Among Adolescents Accra Ghana

Enviado por

Obadele KambonDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Knowledge and Disclosure of Hiv Status Among Adolescents Accra Ghana

Enviado por

Obadele KambonDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Kenu et al.

BMC Research Notes 2014, 7:844

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/7/844

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Open Access

Knowledge and disclosure of HIV status among

adolescents and young adults attending an

adolescent HIV clinic in Accra, Ghana

Ernest Kenu1,3*, Adjoa Obo-Akwa1,2, Gladys B Nuamah1, Anita Brefo1, Miriam Sam1 and Margaret Lartey1,2

Abstract

Background: In Ghana it is estimated that 1.2% of HIV infections occur in young people aged 15-24 but the

representation in our clinics is small. Adherence to treatment, appointment keeping and knowledge of HIV status

remains a challenge. Disclosure has been shown to result in better adherence to therapy, good clinical outcomes,

psychological adjustment and reduction in the risk of HIV transmission when the young person becomes sexually

active. A baseline study was conducted to ascertain if adolescents and young adults knew their HIV status and their

knowledge on HIV. Informed consent and assent were obtained from willing participants. Self-administered

questionnaires on general knowledge of HIV, HIV treatment and disclosure were collected and analyzed.

Results: Thirty-four young persons participated in the study. The mean age was 16.9 SD 2.5 and 62% (21/32)

were female. All of them were still in school. Eighty-five percent were aware that young people their age could fall

sick, 91% had heard of HIV, 70% knew someone with HIV and 45% thought that adolescents were not at risk of HIV.

On modes of HIV transmission, 66.7% knew HIV was transmitted through sex and 63.6% knew about mother to

child transmission. Fifty three percent (18/34) knew their HIV status, 50% (17/34) were on antiretroviral and 35%

(6/17) of them admitted to missing ARV doses. One person who said he was HIV negative and another who did

not know his status were both on ARVs.

Conclusion: Disclosure of HIV status to adolescents and young people is dependent on a complex mix of factors

and most practitioners recommend an age and developmentally appropriate disclosure. Thus it is highly individualized.

The knowledge and awareness of HIV was 91% compared to 97% of adults in the most recent Ghana Demographic

and Health Survey however only about two thirds had acceptable in depth knowledge on HIV. Only half knew their

HIV status which was not the best considering their ages. There is the need to strengthen education to young persons

with HIV, support adhere to ARVs for better outcomes and assist care givers to disclose HIV status to them.

Keywords: Knowledge, Disclosure adolescents/young adults, HIV

Background

Children under 15 years of age account for approximately

3.3 million of the people living with human immune virus

(HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)

worldwide, and almost 90% of all HIV infected children

live in sub-Saharan Africa including Ghana [1]. In Ghana

the prevalence of HIV in young people from 15-24 years is

* Correspondence: Ernest_kenu@yahoo.com

1

Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana

3

Department of Epidemiology and Disease Control, School of Public Health,

College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, P.O. Box LG 13, Legon,

Ghana

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

1.2% [2]. Currently, children infected with HIV through

mother-to-child transmission once diagnosed and in care,

live longer and reach adolescence because of greater access

to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the past decade in West

Africa [3,4]. Thus, with the start of national programme

for providing care and free highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) to children, there has been a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality of HIV infected

children and more of them are surviving through childhood into adolescence with improved quality of life [3].

Along with the increased survival of children infected

with HIV, disclosure of HIV status to children remains a

complex and a critical clinical issue in the care of HIV

2014 Kenu et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain

Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,

unless otherwise stated.

Kenu et al. BMC Research Notes 2014, 7:844

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/7/844

infected children [4]. World Health organization (WHO)

and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) strongly encourage disclosing HIV infection status to school aged

children and younger children. They should be informed

incrementally to accommodate their cognitive skills and

emotional maturity [5,6]. Telling children and adolescents about their HIV infection is a challenging dilemma

because children are often asymptomatic in the early

stages of HIV infection, yet require daily medications

and close monitoring [7].

Caregivers and healthcare workers are presented with

group of challenges around disclosure, including deciding on what is in the childs best interest and when, why

and how information about his/her HIV positive status

should be shared with him/her. Caregivers are reluctant

to disclose the HIV positive status to their children for

fear of social rejection and isolation, parental sense of

guilt, and fear that the child would not keep diagnosis to

themselves [8,9]. Disclosure of HIV status helps HIV infected adolescents to understand their status and the need

for treatment, thereby promoting their participation and

responsibility for their care [10]. The rate of disclosure remains low especially in resource limited countries despite

the growing evidence of the benefits of disclosure [11].

The inability of most caregivers to handle disclosure has

defined the three main patterns of disclosure: complete,

partial, and non-disclosure. Complete disclosure of HIV

status has been associated with improved adherence to

ART [12]. Whereas partial and non-disclosure can strain

the relationship between the caregiver and the child. In

such situations, force and persuasion are often used to get

the child to adhere to treatment; these may results in purposeful rebellion and non-adherence by the child [12].

There is a lot of controversy about what and when to

tell children living with HIV about their diagnosis. Many

families do not think their children can handle the information and they do not want to upset them because

they have already been through so much [8]. Several

studies have documented the benefits of disclosure of

HIV positive status to HIV infected children and adolescents, including psychological benefits as well as positive

effects on the clinical course of the disease [6-9]. The

American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children and adolescents with HIV should be told their diagnosis [6]. However, published rates of disclosure in

children from resource rich countries vary widely, from

18 to 77% [6-9,12], partly due to the lack of conclusive

guidelines on when and how to disclose the diagnosis of

HIV to children.

Though limited, studies available on rates and effects

of HIV disclosure on children are mainly from resource

rich countries. There is paucity of data on disclosure from

resource limited settings, where the majority of HIV

infected children live. Moreover, studies from resource

Page 2 of 6

limited settings have mainly been qualitative in design

with small samples sizes making it difficult to generalize

the findings. This study found out the knowledge and disclosure of HIV status among adolescents and young adults

attending adolescent HIV clinic.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out in July 2013

among HIV infected adolescent and young adults attending an adolescent club meeting in Accra. The Adolescent

HIV Care programme at Fevers unit of Korle-Bu Teaching

Hospital was established in June 2012 and provides comprehensive HIV/AIDS care and management of opportunistic infections. The Unit serves as the national referral

centre for HIV-infected patients. Ever since the first case

of HIV was diagnosed in Ghana in 1986, the Unit has provided care and support to persons living with HIV/AIDS.

Provision of comprehensive HIV/AIDS care and treatment started at the Unit in December 2003 in line with

the scale-up of access to treatment by the National AIDS

Control Programme (NACP) and her partners.

Patients are referred from the paediatric HIV clinic to

the adult clinic at age twelve. Thus the adult clinic serves

both adolescents and adults. An adolescent clinic was

started as best practice when it was recognized that their

needs and expectations were not being met at the adult

clinic. The clinic was supported by adult physicians since

it proved difficult to get the paediatricians to come on

board.

The adolescents and young adults referred to the clinic

present with the following modes of diagnosis: have

mothers known to be HIV seropositive during pregnancy

through the programme for the prevention of mother-tochild transmission (PMTCT), others are discovered to be

infected with HIV after presenting with an AIDS-defining

illness, or are diagnosed after either a symptomatic sibling

or parent was found to be HIV positive. Majority of them

were infected perinatally. At the time of the study, the

adolescent clinic was 13 months old and had about 70

HIV infected adolescents and young adults.

Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital gave the approval for the

formation of the adolescent group as well as the study.

All the young people recruited into the study received

medical care for their HIV infection through the clinic

and were all invited to voluntarily participate in a general survey on HIV infection at one of the club meetings

(Self-selection). Following the self-selection, written informed consent was obtained from those aged 16 years

and above and assent and permission from care givers

for those less than 16 years after briefing on the purpose,

use, and significance of the study. Those who did not

consent were excluded from the survey but continued to

participate in the fun games, music and dance.

Kenu et al. BMC Research Notes 2014, 7:844

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/7/844

A structured questionnaire was then used to collect

data. The questionnaire was anonymous and solicited information on respondents background as well as their

general knowledge on the causes, mode of transmission of

HIV, HIV treatment and disclosure. The questionnaire

had three parts. The first part was closed ended and contained questions on the background of the respondents.

The second part contained questions on general knowledge and awareness of HIV/AIDS found in HIV/AIDS

awareness leaflets used by the Ghana AIDS Commission

for information, education and communication. The final

part of the questionnaire sought respondents views on

HIV status, disclosure and treatment. Here, information

was collected on disclosure status, age at disclosure, treatment compliance, and socio-demographic data, family

type (biologic parents, adoptive/foster, extended), and

care- givers HIV status. Service providers and care givers

were independently interviewed in a focused group discussion on HIV disclosure. The data collected was entered

and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social

Sciences (SPSS; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA)

version 16 with the key issues being presented in summary

frequency tables as descriptive statistics.

Results

Demography of respondents

A total of thirty-four (34) young persons living with HIV

from age 13 to 22 were self-recruited to participate in the

study out of 36 at the adolescent meeting. Thirty four adolescents and young adults did not attend the adolescent

meeting. The mean age of respondents was 16.91 2.5, of

which 61.8% (21/34) were females. All participants were

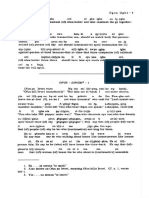

still in school and the distribution is showed in Figure 1.

In relation to religion, 94% (32/34) were Christians and

6% (2/34) were Muslims. The demographic characteristics

of the absentees from the meeting were similar to those

who attended. Of the 8 care givers in the FGD 7 were females and 1 male whereas 75% (6/8) of the service providers in the FGD were females.

Figure 1 Educational level of respondents.

Page 3 of 6

HIV knowledge

Eighty-five percent (29/34) of respondents were aware that

young people of their age could fall sick whilst 5.8% (2/34)

thought otherwise and 8.8% (3/34) did not give any response. Over 91% (31/34) of adolescents had heard of

HIV as compared to 8.8% (3/34) who had no clue. Moreover, 70.6% (24/34) knew someone with HIV whilst the

remaining 29.4% (10/34) did not. Forty-five percent

thought that adolescents were not at risk of getting HIV.

Fifteen percent (5/34) were not sure whether infected patients could continue with their education. Sub-analysis

did not show any statistical difference in HIV knowledge

in terms age, sex and educational status.

Modes of transmission

Majority of the respondents 90.4% (multiple responses)

were able to correctly identify one or more mode of HIV

of transmission with the remaining 9.6% were not able to

provide any correct answers. Out of those who correctly

identified the modes of transmission, 66.7% knew that

HIV could be transmitted through unprotected sexual

intercourse with infected persons and 63.6% knew about

mother to child transmission. Twenty three percent (19/

83 multiple responses) said HIV can be transmitted by

sharing sharp needles/syringes with infected persons.

Overall, 29% (10/34) participants think HIV can be transmitted through physical contact.

The prevalence of HIV disclosure and antiretroviral

therapy

HIV disclosure status rate was 52.9% (18/34), 20.6% (7/

34) said they did not have HIV, 20.6% (7/34) did not

know whether they had it or not and 5.9% (2/34) did not

give any specific answer. Ninety three percent (13/14) of

those who did not know their HIV status were between

13 to 15 years. Fifty percent (17/34) of the respondents

were on antiretroviral whilst 5.9% (2/34) were not, however 26.5% (9/34) did not know whether they were on

ARVs or not. One person who said he was HIV negative

Kenu et al. BMC Research Notes 2014, 7:844

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/7/844

but was on ARVs and 17.6% (6/34) did not give any response. In general, 35% (6/17) of the respondents who

knew they were on ARVs admitted missing some of their

doses Figure 2.

From the FGDs, most of the disclosures happened after

ART initiation and were planned. The persons involved in

this process varied across individual families. It was sometimes disclosed by family members, particularly care givers

or parents after an interview between the latter and a

psychologist. None of the respondents did find out their

status by chance or through unplanned events.

Limitation

The study was carried out in a single adolescent clinic

with a small sample size which may affect generalizability

of our findings.

Discussion

Knowledge of HIV

The study revealed that 90.4% were able to correctly

identify one or more mode of HIV transmission with the

remaining 9.6% not able to provide any correct answer.

The fact that 10% of respondents were ignorant on

mode of HIV transmission even when they were HIV

positive poses serious threats to HIV/AIDS prevention

and control in this age group. It was however not clear

whether this was just ignorance or denial. This study is

in line with findings from other studies done in developing countries such as South Africa and Ethiopia as only

about half knew much about their HIV including their

status even when on anti-retroviral therapy which was

quiet poor [13].

The key to HIV awareness hinges on knowledge of what

HIV and AIDS is, and what exposures and risky behaviors

can potentially lead to contracting the virus. Knowledge of

Figure 2 ART patients knowledge on the type of medication

they are taking.

Page 4 of 6

HIV among infected adolescents and young adults is

therefore crucial not only in preventing the spread of the

virus, but also in addressing the threats posed by HIV/

AIDS. There is the need to strengthen education to young

persons on HIV as well as support care givers to disclose

HIV status and to support young people to adhere to

ARVs for better outcomes.

Status of disclosure

The prevalence of disclosure among our study population was 52.9% (18/34). This is however within the middle bounds of the range (1877%) reported in studies

from resource rich countries. Our finding is consistent

but slightly higher than the reported prevalence of disclosure from Thailand, Zambia, and Uganda of 30.1%,

31.8%, and 29%, respectively [6,7,12,14]. Of the children

who did not know their HIV positive status, more than

two third reportedly were being told of other related

diagnosis like TB, malaria, cholera and the rest did not

have any clue at all about their illness. Reasons cited by

the caregivers for not disclosing HIV status to their

wards were consistent with that of studies in resourcelimited countries; namely stigmatization and isolation,

parental sense of guilt and fear that the child would not

keep diagnosis to themselves [10,15]. As part of standard

of care, disclosure is made to adolescents before transfer

to the adult clinic. We are unable to tell if these were

missed, disclosure was made but not accepted or that

adolescents and care givers were still in denial. Interestingly, some caregivers for fear of stigma reverse what

healthcare providers say as soon as they leave the presence of healthcare providers. However, several studies

from both resource rich and resource limited countries

suggest that the disclosure of HIV status to HIV infected

adolescents and young adults has immense psychological

benefits and positive effects on the clinical course of the

disease [5,12,16,17].

Our findings and that of other studies in the subregion of low rate of disclosure underscore the need for

a systematic review of the hurdles to disclosure and implementation of locally and culturally sensitive interventions programs to promote disclosure.

Nearly a third of the caregivers expected the healthcare providers alone to disclose the HIV status of their

children. This is contrary to European study where majority of caregivers believed that as parents it was their

responsibility to disclose the diagnosis to the child [14].

This may be partly due to the cultural differences in relation to communication between parents and children

on issues and the lack of disclosure skills. The healthcare

providers agreed that disclosure is the prerogative of the

caregivers and children should be told their HIV status.

These contrasting views are consistent with that of studies from resource rich countries [14]. The expectation of

Kenu et al. BMC Research Notes 2014, 7:844

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/7/844

some caregivers that healthcare providers should disclose

the HIV status to the HIV infected adolescents may lead

to unnecessary delays in disclosure. As reiterated by the

healthcare providers, training in disclosure counseling and

a disclosure program adopted by the clinic would allow

healthcare providers to better advice caregivers on how to

disclose. With caregivers who lack disclosure skills, a

counselor assisted or supported disclosure session may

suffice [10].

Transmission of HIV/AIDS

Ninety percent of respondents were able to clearly point

out that HIV/AIDS may be transmitted through having

unprotected sex with an infected partner, being born to

a mother who is infected with HIV, or through the infected mothers breast milk. Which is similar to the 2008

Ghana Demographic and Health survey (GDHS) report

of 97% adult knowledge on HIV transmission [18]. Almost

all the adolescents and young adults were also aware that

using unsterilized instruments or sharing personal items

like toothbrushes could lead to acquiring the virus. Their

awareness has a positive impact on prevention of HIV/

AIDS considering that sharing items like blades, toothbrushes, pins and needles, cooking and pocket knives, hair

and nail clippers, and other sharp objects is a major cause

of transmission in less developed countries [16].

The small proportion (10/34) of participants believed

that physical contact with infected persons or sharing public space with infected persons could be a source of transmission of HIV/AIDS. This might explain the relatively

high stigmatization and discrimination against PLWHA by

their colleagues within some communities in Sub Saharan

Africa [4]. This is in sharp contrast to the content of educational materials and information provided by the Ghana

AIDS Commission, National HIV/AIDS Control Program,

and the mass media on HIV/AIDS transmission. These

materials clearly explain that it is a scientifically proven fact

that physical contact, without the exchange of bodily fluids

with an infected person, cannot transmit the virus. In fact,

a lot of HIV/AIDS awareness messages in Ghana focus on

this point because of the realization that poor awareness of

this fact leads to high stigmatization, seclusion, and discrimination of PLWHA. Such perceptions also explain the

case made by World Bank that PLWHA in rural areas and

less developed countries are sometimes denied access to

public transport, swimming in public pools, fetching water

from public standpipes, engaging in contact sports, and

other activities that involve physical proximity [19].

Believing that physical contact and sharing public space

can lead to HIV infection may result in the adolescent and

young person self-isolation and self-stigmatization. He or

she may not want to socialize and interact for fear of

transmitting the virus or becoming infected. These leads

to poor social skills, lack of support and subsequently

Page 5 of 6

affect adherence and also school work. If such perceptions

are still being held by some people, then prevention and

even management of new and existing cases of HIV/AIDS

may be seriously hindered.

Conclusions

In conclusion, 47% of HIV infected adolescents in the study

were not aware of their HIV status, though strong beneficial

effect of HIV disclosure on retention in care after ART initiation beyond the age of ten is known. Disclosure of HIV

status to adolescents and young people is dependent on a

complex mix of factors and most practitioners recommend

an age and developmentally appropriate disclosure thus it

is highly individualized. The knowledge and awareness of

HIV was 91% compared to 97% of adults in the most recent

Ghana demographic and health Survey. There is the need

to support care givers to disclose HIV status and to support

young people to adhere to ARVs for better outcomes.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients

guardian/parent/next of kin for the publication of this

report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors contributions

Conceived and designed the study: EK, ML, GBN, AOA, MS and AB Performed

the experiments: EK, ML, GBN, AOA, AB and MS. Analyzed the data: ML, EK,

GBN and AOA. Wrote the paper: GBN, EK and ML. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank study participants and the staff of Adolescents/young

adult clinic for their participation in this study.

Author details

1

Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana. 2Department of Medicine and

Therapeutics, University of Ghana Medical School, Accra, Ghana. 3Department

of Epidemiology and Disease Control, School of Public Health, College of

Health Sciences, University of Ghana, P.O. Box LG 13, Legon, Ghana.

Received: 16 July 2014 Accepted: 18 November 2014

Published: 26 November 2014

References

1. Global summary of the AIDS epidemic. http://www.unaids.org/sites/

default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/

2013/gr2013/201309_epi_core_en.pdf.

2. National AIDS/STI Control Programme, Ghana Health Service: HIV Sentinel

Survey Report. 2013.

3. Foster C, Fidler S: Optimizing antiretroviral therapy in adolescents with

perinatally acquired HIV-1 infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2010,

8:14031416. doi:10.1586/eri.10.129. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google

Scholar.

4. Eng E, Maman S, Tshikandu T, Behets F, Vaz LM: Telling children they have

HIV: lessons learned from findings of a qualitative study in sub-Saharan

Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010, 24:247256.

5. World Health Organization: Guideline on HIV disclosure counselling for

children up to 12 years of age. 2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/

publications/2011/9789241502863_eng.pdf.

Kenu et al. BMC Research Notes 2014, 7:844

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/7/844

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

Page 6 of 6

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatrics AIDS: Disclosure

of illness status to children and adolescents with HIV infection.

Pediatrics 2010, 103:164166.

Menon A, Glazebrook C, Campain N, Ngoma M: Mental health and

disclosure of HIV status in Zambian adolescents with HIV infection:

implications for peer-support programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007,

46:349354.

Lee CL, Johann-Liang R: Disclosure of the diagnosis of HIV/ AIDS to

children born of HIV-infected mothers. AIDS Patient Care STDS 1999,

13:4145.

Vaz L, Corneli A, Dulyx J, Rennie S, Omba S, Kitetele F, Behets F, AD

Research Group: The process of HIV status disclosure to HIV-positive

youth in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. AIDS Care 2008,

20:842852.

Bachanas PJ, Kullgren KA, Schwartz KS, Lanier B, McDaniel JS, Smith J,

Nesheim S: Predictors of psychological adjustment in school-age children

infected with HIV. J Pediatr Psychol 2001, 26:343352.

Mahloko JM, Madiba S: Disclosing HIV diagnosis to children in Odi district,

South Africa: reasons for disclosure and non-disclosure. Afr J Prm Health

Care Fam Med 2012, 4:17.

Bikaako-Kajura W, Luyirika E, Purcell DW, Downing J, Kaharuza F, Mermin J,

Malamba S, Bunnell R: Disclosure of HIV status and adherence to daily

drug regimens among HIV- infected children in Uganda. AIDS Behav

2006, 10:S85S93.

Demmer C: Experiences of families caring for an HIV-infected child in

KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: an exploratory study. AIDS Care 2011,

23:873879.

Thorne C, Newell ML, Peckham CS: Disclosure of diagnosis and planning

for the future in HIV-affected families in Europe. Child Care Health Dev

2000, 26:2940.

Moore AR, Williamson D: Disclosure of childrens positive serostatus to

family and nonfamily members: informal caregivers in Togo, West Africa.

AIDS Res Treat 2011, 2011:595301.

Ferris M, Burau K, Schweitzer AM, Mihale S, Murray N, Preda A, Ross M, Kline

M: The influence of dis-closure of HIV diagnosis on time to disease

progression in a cohort of Romanian children and teens. AIDS Care 2007,

19:10881094.

Siu GE, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Kennedy CE, Dhabangi A, Kambugu A: HIV serostatus

disclosure and lived experiences of adolescents at the Transition Clinic of

the Infectious Diseases Clinic in Kampala, Uganda: a qualitative study.

AIDS Care 2012, 24:606611.

Ghana Demographic Health Survey Report. 2008.

World Bank: HIV/AIDS prevention and Care Strategies for HIV; 2010. Retrieved

from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EDUCATION/Resources/2782001099079877269/547664-1099080042112/Edu_HIVAIDS_window_hope.pdf.

doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-844

Cite this article as: Kenu et al.: Knowledge and disclosure of HIV status

among adolescents and young adults attending an adolescent HIV

clinic in Accra, Ghana. BMC Research Notes 2014 7:844.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and take full advantage of:

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

No space constraints or color gure charges

Immediate publication on acceptance

Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Você também pode gostar

- Evolving EarthDocumento38 páginasEvolving EarthObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Wadi Al-JarfDocumento22 páginasWadi Al-JarfObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Wadi Al-JarfDocumento22 páginasWadi Al-JarfObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Sandro Capo Chichi: (Texte)Documento34 páginasSandro Capo Chichi: (Texte)Obadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- 1st African Regional Martial Arts CongressDocumento8 páginas1st African Regional Martial Arts CongressObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Remarks On A Few "Polyplural" Classes in Bantu: Africa & Asia, No 3, 2003, PP 161-184Documento24 páginasRemarks On A Few "Polyplural" Classes in Bantu: Africa & Asia, No 3, 2003, PP 161-184Obadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Egyptian, Hieroglyphs, In, Five, Weeks, A, Crash, Course, In, The, Script, And, Language, Of, The, Ancient, Egyptians, IDocumento2 páginasEgyptian, Hieroglyphs, In, Five, Weeks, A, Crash, Course, In, The, Script, And, Language, Of, The, Ancient, Egyptians, IObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- ACTFLProficiencyGuidelines2012 FINALDocumento53 páginasACTFLProficiencyGuidelines2012 FINALObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Inherent Complement Verbs - Sampson KorsahDocumento26 páginasInherent Complement Verbs - Sampson KorsahObadele Kambon100% (1)

- Ghana Beads HandoutDocumento2 páginasGhana Beads HandoutObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Ifa Divination PDFDocumento2 páginasIfa Divination PDFObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Radical Caribbean Social Thought: Race, Class Identity and The Postcolonial NationDocumento19 páginasRadical Caribbean Social Thought: Race, Class Identity and The Postcolonial NationObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Anubis - The God's Manifestation in The Iconographical and Literary Sources of The Pharaonic PeriodDocumento140 páginasAnubis - The God's Manifestation in The Iconographical and Literary Sources of The Pharaonic PeriodObadele Kambon100% (1)

- Wiley Ethics - Guidelines - 7.06.17 PDFDocumento29 páginasWiley Ethics - Guidelines - 7.06.17 PDFObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Ife 6 Year ProjectDocumento193 páginasIfe 6 Year ProjectObadele Kambon100% (2)

- Cifar: Connecting The Best Minds For A Better WorldDocumento1 páginaCifar: Connecting The Best Minds For A Better WorldObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- AASR Bulletin 45 - 2 PDFDocumento101 páginasAASR Bulletin 45 - 2 PDFObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Bantoid Languages in KoelleDocumento1 páginaBantoid Languages in KoelleObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- 2010 Ptolemaic HieroglyphsDocumento11 páginas2010 Ptolemaic HieroglyphsShihab EldeinAinda não há avaliações

- Pankhurst Richard Italian Fascist War CrimesDocumento59 páginasPankhurst Richard Italian Fascist War CrimesObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- Ifa Divination PDFDocumento2 páginasIfa Divination PDFObadele KambonAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- 2021-2022 Business French BCAD 108-Detailed Course OutlineDocumento5 páginas2021-2022 Business French BCAD 108-Detailed Course OutlineTracy AddoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 8Documento5 páginasChapter 8Bernadette PononAinda não há avaliações

- Cumberland Youth Football Registration 2021Documento3 páginasCumberland Youth Football Registration 2021api-293704297Ainda não há avaliações

- Field Experience Assignment #1: Become Familiar With The SchoolDocumento6 páginasField Experience Assignment #1: Become Familiar With The Schoolapi-511543756Ainda não há avaliações

- The V ttaRatnaKara and The ChandoMañjarī. Patgiri Ritamani, 2014Documento154 páginasThe V ttaRatnaKara and The ChandoMañjarī. Patgiri Ritamani, 2014Srinivas VamsiAinda não há avaliações

- Daily Time Record Daily Time Record: Saturday SundayDocumento13 páginasDaily Time Record Daily Time Record: Saturday Sundaysingle ladyAinda não há avaliações

- Roya Abdoly ReferenceDocumento1 páginaRoya Abdoly Referenceapi-412016589Ainda não há avaliações

- Course Outline Pre-Calc Math 12Documento2 páginasCourse Outline Pre-Calc Math 12api-709173349Ainda não há avaliações

- Modified Double Glove TechniqueDocumento1 páginaModified Double Glove TechniqueSohaib NawazAinda não há avaliações

- EappDocumento19 páginasEappdadiosmelanie110721Ainda não há avaliações

- Translation Services in Hong KongDocumento12 páginasTranslation Services in Hong KongAnjali ukeyAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Thinking QuestionsDocumento2 páginasCritical Thinking QuestionsJulie Ann EscartinAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 5 Mock Paper1Documento78 páginasUnit 5 Mock Paper1SahanNivanthaAinda não há avaliações

- Rubric Shom Art Exploration Shoe DrawingDocumento1 páginaRubric Shom Art Exploration Shoe Drawingapi-201056542100% (1)

- Project Proposal I. Project Title II. Theme Iii. Ifp Goal IV. Implementation Date V. VenueDocumento7 páginasProject Proposal I. Project Title II. Theme Iii. Ifp Goal IV. Implementation Date V. VenueJay Frankel PazAinda não há avaliações

- Dolphin Readers Level 1 Number MagicDocumento19 páginasDolphin Readers Level 1 Number MagicCharles50% (2)

- Anurag Goel: Principal, Business Consulting and Advisory at SAP (Among Top 0.2% Global SAP Employees)Documento5 páginasAnurag Goel: Principal, Business Consulting and Advisory at SAP (Among Top 0.2% Global SAP Employees)tribendu7275Ainda não há avaliações

- Handout Sa Personal Development G 11Documento2 páginasHandout Sa Personal Development G 11Alecks Luis JacobeAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 3 - A Person You AdmireDocumento6 páginasLesson 3 - A Person You AdmireBen English TVAinda não há avaliações

- Why Women Wash DishesDocumento9 páginasWhy Women Wash Dishesmoodswingss100% (1)

- Assignment 1Documento3 páginasAssignment 1SourabhBharatPanditAinda não há avaliações

- The Reaction Paper, Review, and CritiqueDocumento16 páginasThe Reaction Paper, Review, and CritiqueChristian PapaAinda não há avaliações

- On Your Date of Joining, You Are Compulsorily Required ToDocumento3 páginasOn Your Date of Joining, You Are Compulsorily Required Tokanna1808Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 Research PaperDocumento5 páginasChapter 1 Research PaperMae DeloriaAinda não há avaliações

- Trainee'S Record Book: Muñoz National High SchoolDocumento8 páginasTrainee'S Record Book: Muñoz National High SchoolGarwin Rarama OcampoAinda não há avaliações

- Proverbs 1: Prov, Christ's Death in TheDocumento24 páginasProverbs 1: Prov, Christ's Death in TheO Canal da Graça de Deus - Zé & SandraAinda não há avaliações

- TestAS-Economic-2017 (Second Edition)Documento16 páginasTestAS-Economic-2017 (Second Edition)Thanh VuAinda não há avaliações

- Les FHW 10Documento17 páginasLes FHW 10Parvez TuhenAinda não há avaliações

- Steps in Successful Team Building.: Checklist 088Documento7 páginasSteps in Successful Team Building.: Checklist 088Sofiya BayraktarovaAinda não há avaliações