Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Business Process Analysis

Enviado por

Eric BrittenDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Business Process Analysis

Enviado por

Eric BrittenDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Business Process Analysis

Using Detail Process Maps and the Questioning Method1

By Ben B Graham

Copyright 2007, The Ben Graham Corporation. All rights reserved.

Permission is granted to post, print and distribute this document in its original PDF format.

Reengineering, ISO Certification, Business Process Improvement, Six Sigma,

Sarbanes-Oxley all specify an organizational focus on business processes,

however, none provides a specific method for understanding the processes. This

leaves many people attempting to figure it out as they go. Without a solid

methodology to support process understanding and improvement, many efforts

fail, drag on, or (at best) require more effort than was initially anticipated. Detail

process charts provide a level of understanding that is essential for effective

analysis. They have been used by world-class organizations to achieve excellent

results for over half a century.

Real bottom line value is derived from process maps when they are used to

improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the processes. Often the motivation

that leads to conducting an improvement project is to correct a problem such as:

the process has generated costly errors, the process takes too long, the process

has failed an audit, the process is not in compliance with new legislation, the

process has broken down, etc.

Unfortunately, the urgency that generates improvement projects encourages

shortsighted decisions. Believing that detailed charting will take too long, no

map is prepared or if a map is prepared it is at such a high level that it shows

only what most people already know. (Actually the time required to prepare

detailed process charts is generally misunderstood, usually overestimated. Most

processes can be easily mapped in detail in a day or two.) Without the thorough

and comprehensive view provided by a detailed process chart, the improvement

effort results in changes that correct or lessen the initial problem while often

causing undesirable side effects. The more complex the process, the more likely

the fix will cause new problems. Where managers are alert to the risk of negative

side effects they sometimes opt to leave the current process in place untouched

and add a totally separate process to address the current problem, further

complicating the processes.

Fortunately, the ease with which well‐drawn process maps enable people to see

what is causing problems and how to correct them makes it is faster to do it right

than to cut corners. Assemble a team of people who are involved in the process.

Prepare a map of the process as is it now, an “As‐is” map. Walk through the

Business Process Analysis worksimp.com processchart.com

map with the team. If the project exists to resolve an urgent problem, state the

problem in terms of objectives and post the objectives in large print in front of

the team as a constant reminder while they work (i.e. to eliminate errors, to

reduce cycle time, to fix specific flaws noted in an audit, to comply with new

legislation, etc.) Then have the team challenge the process step by step.

Sometimes people who are trying to improve get so excited about the first few

ideas that surface, they commit to them and close their minds to further

opportunities. The following questions provide a pattern that can help a team

think through a process thoroughly, spotting far more opportunities and arriving

at top quality solutions.

The Questioning Method

“I have six honest serving men (they taught me all I knew); their names are What and

Why and When and How and Where and Who.” Rudyard Kipling

In defining a process, our objective is to capture reality; to paint a realistic picture

of what the process does. We ask what is happening at every step along the way.

We also capture where the work is done, who does the work and when the work is

done. We don’t ask why, because it doesn’t matter…yet.

With a good process story in front of a team of people who represent the process

(and really understand their piece of it), it is time to ask why. Now we ask the

same questions that we asked to define the process…but, this time we ask why to

every answer.

During analysis, every question becomes two questions. At each step, we ask

first “What is happening? And to the answer of that question we ask, “Why?”

Why are we doing this? Is it necessary? Can it be eliminated? If there isn’t a

good reason for doing that step, recommend that it be eliminated. This is the

question that produces the most cost effective changes and should always be

asked first. There is no sense in asking more detailed questions about a work

step that should not be done at all. When steps of work are eliminated there is

little or no implementation cost and the benefit equals the full cost of the

performing that step. Many work steps that once served a valuable purpose

(possibly years ago) can be eliminated when that purpose no longer exists.

If there is a good reason for performing the step then ask; “Where is it done and

why is it done there?” ‐ “When is it done and why is it done at that time?” –

“Who does it and why does that person do it?” These questions lead to changes

in location, timing, and the person doing the work without changing the task

itself and therefore they are also highly cost effective. Equipment is relocated

Business Process Analysis worksimp.com processchart.com

closer to the people who use it. Schedules are revised to fit with previous and

following portions of the process to produce smoother flow. Tasks are shifted to

people better able to perform them. Tasks are combined, eliminating the

transports and delays between them that occurred as the work flowed between

locations and/or people.

Only after these questions have been asked and answered should the final

question be addressed; “How is it done and why is it done that way?” While this

question can lead to excellent benefits, it also incurs the greatest costs because

changing how a task is done generally requires introducing new technology with

new equipment, programming and significant amounts of training. Of course,

new technology is important. It is very important, and it should be pursued.

But, if the organization wants to maximize profits, it will hold off on changing

how the steps are performed until after the previous questions have been

properly dealt with. (Unfortunately, new technology is so enticing that

organizations often leap into it before asking the earlier questions. They miss

easy to install, high payoff opportunities and sometimes wind up having spent a

lot of money to automate activities that shouldn’t be done at all.)

Using these questions with a process map provides team members with fresh

eyes to see their work from a new vantage point. They are used to doing the

work. They are not used to seeing it as symbols and lines, and as a part of a

process. From this new perspective, opportunities for improvement become

apparent, and since the people doing the study are thoroughly familiar with the

work, their improvements are almost always realistic, practical and doable.

As team members work their way through the “As‐is” map they come up with

numerous changes that are easily displayed in a revised map. When they have

done this two or three times, they arrive at a map that represents the process as

they would like it to be ‐ a “To‐be” map. Now they have two maps, the “As‐is”

and the “To‐be”, both drawn step‐by‐step using precisely the same mapping

terminology, which paves the way for methodical handling of approval and

implementation activities.

Ben B Graham is President of The Ben Graham Corporation and author of the book ‘Detail Process

Charting: Speaking the Language of Process’ published by John Wiley Publishers. His company pioneered

the field of business process improvement, and has provided process improvement consulting, coaching

and education services to organizations across North America since 1953. Ben has worked with many

organizations to build libraries of business process maps and develop effective, process-focused,

continuous improvement programs. His organization publishes Graham Process Mapping Software, which

is designed solely for preparing detail process maps. More information about the software is available at

http://www.processchart.com

1 Excerpted from Ben B Graham, Detail Process Charting: Speaking the Language of Process (John Wiley & Sons, 2004)

Business Process Analysis worksimp.com processchart.com

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Sample Exam TGLS Grammar and VocabularyDocumento5 páginasSample Exam TGLS Grammar and VocabularycooladillaAinda não há avaliações

- One-week-Lesson-Plan The Present Simple Tense by Pei Ching ChenDocumento8 páginasOne-week-Lesson-Plan The Present Simple Tense by Pei Ching Chenpeic100% (2)

- 21day Studyplan For LLQP ExamDocumento9 páginas21day Studyplan For LLQP ExamMatthew ChambersAinda não há avaliações

- Transformation of SentencesDocumento30 páginasTransformation of SentencesSasa Milosevic100% (9)

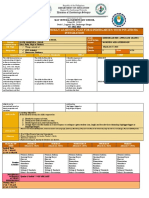

- Lesson Plan Grade GRADE 11Documento3 páginasLesson Plan Grade GRADE 11Catherine Panerio100% (2)

- How To - A Guide To Using Qualtrics Research SuiteDocumento16 páginasHow To - A Guide To Using Qualtrics Research SuiteRodrigo BassoAinda não há avaliações

- Tle JanuaryDocumento10 páginasTle JanuaryRonnel Andres Hernandez67% (3)

- CLO Assignment PDFDocumento4 páginasCLO Assignment PDFm azfar tariqAinda não há avaliações

- Coursework 1 - Brief and Guidance 2018-19 FinalDocumento12 páginasCoursework 1 - Brief and Guidance 2018-19 FinalHans HoAinda não há avaliações

- Advanced Psychology SyllabusDocumento8 páginasAdvanced Psychology SyllabuscontroversialblackneAinda não há avaliações

- INTERVIEW Sample Question and AnswerDocumento17 páginasINTERVIEW Sample Question and AnswerRazell Dela PeñaAinda não há avaliações

- Pass College Senior High School Department Oral Communication Quiz 1Documento2 páginasPass College Senior High School Department Oral Communication Quiz 1Hazel Abella100% (1)

- NIFT, MFM Mock TestDocumento8 páginasNIFT, MFM Mock TestBlacksheepResources100% (1)

- Unfamiliar Words: Lesson 13Documento17 páginasUnfamiliar Words: Lesson 13RobertAinda não há avaliações

- 1st Grading Lesson Plan English ViDocumento83 páginas1st Grading Lesson Plan English ViMike Oliver Gallardo86% (7)

- Week5-Q3 - Wlp-Dll-With PSS and HG IntegrationDocumento10 páginasWeek5-Q3 - Wlp-Dll-With PSS and HG IntegrationMary Jane YangaAinda não há avaliações

- Implied Detail Questions 6Documento8 páginasImplied Detail Questions 6MarcellaAinda não há avaliações

- Speaking - FrenchDocumento32 páginasSpeaking - FrenchphanikrishnaakellaAinda não há avaliações

- Listening and Speaking NotesDocumento34 páginasListening and Speaking NotesMadam MAinda não há avaliações

- Communications Kils in English 6801Documento13 páginasCommunications Kils in English 6801Gopalkrishna GopalAinda não há avaliações

- Celta Handbook Ih New (July 2014)Documento111 páginasCelta Handbook Ih New (July 2014)hasteslideAinda não há avaliações

- 4 As Lesson PlanDocumento8 páginas4 As Lesson PlanjoeAinda não há avaliações

- ANT 302 Ethnographic Assignment 2019Documento1 páginaANT 302 Ethnographic Assignment 2019WeaselmonkeyAinda não há avaliações

- Personal Statements vs. Statements of Purpose PPT PDFDocumento11 páginasPersonal Statements vs. Statements of Purpose PPT PDFshambelAinda não há avaliações

- IELTS Essay StructuresDocumento6 páginasIELTS Essay StructuresGhs MuraliwalaAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of LAUGHTER-CAUSING UTTERANCES IN STAND-UP COMEDY - Abu Yazid BusthamiDocumento128 páginasAnalysis of LAUGHTER-CAUSING UTTERANCES IN STAND-UP COMEDY - Abu Yazid Busthamisanggar at-ta'dibAinda não há avaliações

- Energize 1 TGDocumento24 páginasEnergize 1 TGRuxyAinda não há avaliações

- English 2nd Language MQP-3 2015 (Modified)Documento8 páginasEnglish 2nd Language MQP-3 2015 (Modified)ultimatorZAinda não há avaliações

- MosDocumento22 páginasMosJAy RastaAinda não há avaliações

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: 9093/22 English LanguageDocumento4 páginasCambridge International AS & A Level: 9093/22 English LanguagereemAinda não há avaliações