Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Dollar WorldBank GlobalizationPovertyAndInequalitySince1980 2005 PDF

Enviado por

Anonymous ft3QxaxiTuTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Dollar WorldBank GlobalizationPovertyAndInequalitySince1980 2005 PDF

Enviado por

Anonymous ft3QxaxiTuDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

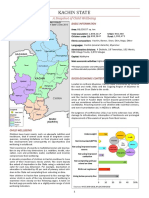

Globalization, Poverty, and Inequality since 1980

Author(s): David Dollar

Source: The World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Fall 2005), pp. 145-175

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41261414 .

Accessed: 11/05/2013 04:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The World

Bank Research Observer.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Globalization,Poverty,and Inequality

since 1980

DavidDollar

One ofthemostcontentiousissues ofglobalizationis theeffect ofglobal economicintegra-

tionon inequalityand poverty. This articledocuments five trendsin themodernera ofglo-

balization,startingaround 1 980. Thefirsttrendis thatgrowthrates in poor economies

have acceleratedand are higherthan growthrates in richcountriesfor thefirsttimein

modernhistory.Developingcountries9 per capita incomesgrew more than 3.5 percenta

year in the 1 990s. Second,the number ofextremelypoorpeoplein theworldhas declined

significantly by 375 millionpeople since 1981 - for the timein history.The share of

-

peoplein developing economieslivingon less than$la day has beencutin halfsince 1981,

thoughthe declinein the share livingon less than $2 per day was much less dramatic.

Third,global inequalityhas declinedmodestly,reversinga 200-year trendtowardhigher

inequality.Fourth,within-country inequalityin generalis notgrowing,thoughit has risen

in severalpopulous countries(China, India, the UnitedStates). Fifth,wage inequalityis

risingworldwide.This may seem to contradictthefourthtrend,but it does not because

thereis no simplelinkbetweenwage inequalityand householdincomeinequality.Further-

more,the trendstowardfastergrowthand povertyreductionare strongestin developing

economiesthathave integratedwiththeglobaleconomymostrapidly,whichsupportsthe

viewthatintegration has beena positiveforceforimprovingthelivesofpeoplein developing

areas.

Globalization

has dramatically betweenand within

increasedinequality

nations.

-Jay Mazur(2000)

issoaringthrough

Inequality theglobalization within

period, and

countries

Andthat'sexpected

acrosscountries. tocontinue.

- NoamChomsky

Presson behalfoftheInternational

The Author2005. PublishedbyOxfordUniversity and

BankforReconstruction

Development/theworldbank.Allrights

reserved. pleasee-mail:journals.permissions@oupjournals.org.

Forpermissions,

doi:10.1093/wbro/lki008 20:145-175

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Allthemainparties

support nonstop

expansioninworldtradeandservices

we

although allknow it... makes

rich richer

people andpoorpeoplepoorer.

- WalterSchwarz,TheGuardian

Weareconvinced thatglobalization

isgoodandit'sgoodwhenyoudoyour

homework... keepyour fundamentals in lineon theeconomy, buildup

highlevelsofeducation,

respectruleoflaw. . . whenyoudo yourpart,we

areconvincedthatyougetthebenefit.

- President Vicente

FoxofMexico

Thereis no wayyoucan sustaineconomicgrowthwithout

accessinga big

andsustainedmarket.

- President

YoweriMuseveni

ofUganda

Wetakethechallenge ofinternational

competitionina levelplayingfield

as

an incentive

todeepenthereform for

process the overall sustaineddevelop-

mentoftheeconomy, wtomembership workslikea wrecking ball,smashing

whateverisleftintheoldedifice

oftheformerplannedeconomy.

- JinLiqun,ViceMinister ofFinanceofChina

Thereisan odddisconnect between debatesaboutglobalization indeveloped econo-

miesand developing economies. Amongintellectuals in developed

areasoneoften

hearstheclaimthatglobaleconomicintegration is leadingtorisingglobalinequal-

- thatis,thatintegration

ity benefitsrichpeopleproportionally morethanpoorpeo-

ple. In the extremeclaimspoorpeopleare actuallymade out to be worseoff

absolutely (as in theepigraphfromSchwarz).In developing economies, though,

intellectualsandpolicymakers oftenviewglobalization as providing

goodopportuni-

tiesfortheircountries andpeople.To be sure,theyarenothappywiththecurrent

stateofglobalization. Theepigraph fromPresident YoweriMuseveni, forexample,

comesfrom a speechthatblastsrichcountries fortheirprotectionism againstpoor

countries andlobbiesforbetter market access.Butthepointofthesecritiques isthat

-

integrationthrough trade,foreign

foreign investment, -

andimmigrationis basi-

a for

cally goodthing poor countries and thatrich countries coulddo a lotmoreto

facilitate -

integrationthatis,makeitfreer. Theclaimsfrom antiglobalization intel-

lectualsinrichcountries, however, leadinescapably totheconclusion thatintegra-

tionis bad forpoorcountries and thattherefore tradeand otherflowsshouldbe

morerestricted.

Thefirst goalofthisarticleis todocument whatis knownabouttrends in global

inequality andpoverty overthelongtermandduringtherecentwaveofglobaliza-

tionthatbeganaround1980. Globalinequality is usedtomeandifferent thingsin

146 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 (Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

different - distribution

discussions amongall thecitizens oftheworld,distribution

within distribution

countries, amongcountries,distributionamongwageearners -

all ofwhichare usedin thisarticle.A secondgoal ofthearticleis to relatethese

trendstoglobalization.

Thefirst discusses

sectionbriefly thegrowing integrationofdeveloping economies

withindustrialized andwitheachother,

countries startingaround 1980. The opening

oflargedeveloping suchas ChinaandIndia,isarguably

countries, themostdistinctive

featureofthiswaveofglobalization.

Thesecondsection, theheartofthearticle, pre-

sentsevidenceinsupport in

offivetrends inequality

andpoverty since1980:

Growth ratesin poorcountries have acceleratedand are higherthangrowth

ratesinrichcountries timeinmodern

forthefirst history.

Thenumber ofextremely poorpeople(thoselivingonlessthan$1 a day)inthe

worldhas declinedsignificantly- by 375 millionpeople- forthefirst

timein

history,though thenumber livingon lessthan a

$2 day has increased.

Globalinequality has declinedmodestly, a 200-yeartrendtoward

reversing

higher inequality.

Within-country inequalityisgenerallynotgrowing.

Wageinequality is risingworldwide. Thismayseemto contradict thefourth

trend,butitdoesnotbecausethereis no simplelinkbetweenwageinequality

andhousehold incomeinequality.

Thethirdsectionthentriestodrawa linkbetweentheincreased integrationand

acceleratedgrowthandpoverty reduction.

Individual cases,cross-country statisti-

cal analysis,and micro-evidence fromfirmsall suggestthatopeningto tradeand

directinvestment has beena goodstrategy forsuchcountries as theChina,India,

Mexico,Uganda,andVietnam. Theconclusions forpolicyin thefourth sectionare

very much in the of

spirit the comments fromPresidents Fox and Museveni. Devel-

opingeconomies havea lottodo todevelopin generalandtomakeeffective use of

as

integrationpart oftheirdevelopment strategy.Richcountries coulddo a lotmore

withforeign aidtohelpwiththatwork.AsMuseveni accesstomarkets

indicates, in

richcountries isimportant.A lotofprotections

remaininOrganisation forEconomic

Co-operationandDevelopment (oecd)markets

from thegoodsandpeopleofdeveloping

economies,andglobalization wouldworkmuchbetter forpoorpeopleifdeveloping

areashadmoreaccesstothosemarkets.

GrowingIntegrationbetween Developed and Developing

Economies

Globaleconomic hasbeengoingonfora longtime.In thatsense,global-

integration

izationis nothing

new.Whatis newinthismostrecentwaveofglobalization is the

DavidDollar 147

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

way developingcountriesare integrating

withrichcountries.As in previouswaves

thischange is drivenpartlyby technologicaladvances in transport

ofintegration,

and communications and partlybydeliberatepolicychoices.

EarlierWavesof Globalization

From 1820 to 1870 the worldhad alreadyseen a fivefold increasein the ratioof

trade to gross domesticproduct(gdp)(table 1). Integrationincreasedfurtherin

18 70-1 914, spurredbythedevelopment ofsteamshippingand byan Anglo-French

tradeagreement.In thisperiodthe worldreached levels of economicintegration

comparablein manyways to thoseoftoday.The volumeoftraderelativeto world

incomenearlydoubledfrom10 percentin 1870 to 18 percenton theeve ofWorld

WarI. Therewerealso largecapitalflowsto rapidlydeveloping partsoftheAmericas,

and theownershipofforeignassets(mostlyEuropeansowningassetsin othercoun-

tries)morethan doubledin thisperiod,from7 percentofworldincometo 18 per-

cent. Probablythe most distinctivefeatureof this era of globalizationwas mass

migration.Nearly10 percentofthe world'spopulationpermanently relocatedin

this period (Williamson2004). Much of this migrationwas frompoor parts of

Table 1. MeasuresofGlobalIntegration

CapitalFlows TradeFlows andCommunications

Transport Costs(constant

US$)

Sea Freight TelephoneCall

(averageocean AirTransport (averagepricefora

Assets/

Foreign freight andport (averagerevenue 3-minutecallbetween

Year Worldgdp(%) Trade/

gdp(%) charges perton) perpassengermile) NewYorkandLondon

1820 - 2 - - -

1870 6.9 10 - - -

1890 - 12 - - -

1900 18.6 - - - -

1914 17.5 18 - - -

1920 - - 95 - -

1930 8.4 18 60 0.68 245

1940 - - 63 0.46 189

1945 4.9 - - - -

1950 - 14 34 0.30 53

1960 6.4 16 27 0.24 46

1970 - 22.4-20 27 0.16 32

1980 17.7 - 24 0.10 5

1990 - 26 29 0.11 3

1995 56.8 - - - -

Source:Crafts(2000) forcapitalflows;Maddison(1995) and Crafts(2000) fortradeflows;WorldBank (2002)

fortransport

and communications costs.

- notavailable.

148 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 (Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EuropetotheAmericas. Buttherewas alsoconsiderable migration from Chinaand

India(muchofitforced in

migration India). While globalindicators showed consid-

erableintegrationin 1870-1914,thiswas alsotheheydayofcolonialism, andmost

oftheworld'speopleweregreatly restrictedintheiropportunities tobenefit from the

expanding commerce.

Globalintegration tooka bigstepbackwardduringthetwoworldwarsand the

GreatDepression. Somediscussions ofglobalizationtodayassumeitwas inevitable,

butthisdarkperiodisa powerful reminder thatpoliciescanhaltandreverse integra-

tion.Bytheendofthisdarkerabothtradeand foreign assetownership wereback

closetotheirlevelsof1870- theprotectionist periodundid50 yearsofintegration.

The era offreemigration was also at an end,as virtually all countries imposed

onimmigration.

restrictions

FromtheendofWorldWarII to about1980, industrialized countries restored

muchoftheintegration thathad existedamongthem.Theynegotiated seriesofa

mutualtradeliberalizations undertheauspiceoftheGeneralAgreement on Tariffs

andTrade.Butliberalization ofcapitalflowsproceeded moreslowly,and notuntil

1980 didthelevelofownership offoreign assetsreturned toits1914 level.Overthis

period therewas also modest liberalization ofimmigration in manyindustrialized

countries,especiallytheUnitedStates.In thispostwar periodofglobalization, many

developing economies chose to sit on the sidelines.

Most developing areas in Asia,

Africa,andLatinAmericafollowed import-substitutingindustrializationstrategies,

keeping theirlevelsofimportprotection farhigher than inindustrialized countriesto

encourage domestic production of manufactures and usuallyrestricting foreign

investment bymultinational firms toencourage thegrowth ofdomestic firms. While

limitingdirect investment,several developing economies turned to the expanding

internationalbankborrowing sectorinthe1970s andtookon significant amounts

offoreigndebt.

RecentWaveofGlobalization

Themostrecentwaveofglobalization startedin 1978 withtheinitiationofChina's

economicreform and openingto theoutsideworld,whichroughly coincideswith

thesecondoil shock,whichcontributed to externaldebtcrisesthroughout Latin

Americaand in otherdeveloping economies.In a growing numberofcountries in

LatinAmerica,SouthAsia,andSub-Saharan Africa political leaders

andintellectual

begantofundamentally rethinkdevelopment strategies. partofthis

Thedistinctive

isthatthemajority

latestwaveofglobalization ofdevelopingeconomies(interms of

population)shiftedfroman inward-focused strategyto a moreoutward-oriented

one.

Thisalteredstrategy can be seenin thehugeincreasesin tradeintegration of

developingareasoverthepasttwodecades.China'sratiooftradetonationalincome

DavidDollar 149

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

has morethandoubled,andcountries suchas Mexico,Bangladesh, Thailand,and

Indiahaveseenlargeincreases as well(figure1). Butseveraldevelopingeconomies

tradelessoftheirincomethantwodecadesago,a factthatwillbe discussed later.

The changehas notbeenonlyin theamount,butalso in thenatureofwhatis

traded.Twentyyearsago, nearly80 percentofdeveloping country merchandise

exportswere primary the of

products: stereotype poor countries exportingtinor

bananashada largeelement oftruth. Thebigincreaseinmerchandise exportsinthe

pasttwo decades, however,has been ofmanufactured products,so that80 percent

oftoday'smerchandise from

exports developingcountriesaremanufactures (figure 2).

Garments from CD

Bangladesh, players from China, from

refrigerators Mexico, and

computer from

peripherals Thailand- thesearethemodern faceofdevelopingeconomy

exports.Serviceexports fromdeveloping areashave also increasedenormously -

bothtraditional suchas tourism,

services, andmodern ones,suchas software from

Bangalore,India.

Manufactured exportsfromdeveloping economies areoften partofmultinational

production networks. Nikecontracts withfirmsin Vietnamto makeshoes;the

"worldcar" is a reality,

withpartsproducedin different locations.So partofthe

answertowhyintegration has takenoffmustliewithtechnological advancesthat

Figure 1. ChangeinTradeas a Shareofgdp,SelectedCountries,

1977-97 (%)

Source:WorldBank(2002).

150 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 (Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Figure2. Developing

Country bySector,1965-99 (% oftotal)

Exports

Manufactures

^f

^i*^

20- ^^^^ ^^Minerals

Agriculture V '

^ "i I I I I I l

1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995

Source: World Bank (2002).

makeintegrated production feasible(seetable1 forevidence ofthedramatic declines

in thecostofair transport and international communications). But partofthe

answeralso liesin policychoicesofdeveloping economies.Chinaand Indiahad

almosttotallyclosedeconomies, so theirincreased integrationwouldnothavebeen

without

possible stepstogradually liberalize

tradeanddirect foreign investment.

Somemeasureofthispolicytrendcan be seenin averageimport tariff

ratesfor

developingeconomies. Since1980 averagetariffs have declinedsharplyin South

Asia,LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean, andEastAsiaandPacific, whereasinAfrica

andtheMiddleEasttherehasbeenmuchlesstariff-cutting (figure3). Thesereported

averagetariffs,

however, captureonlya smallamountofwhatis happening with

tradepolicy.Often themostpernicious impediments are nontariffbarriers: quotas,

schemes,

licensing restrictions

onpurchasing exchangeforimports,

foreign andthe

like.Chinastarted to reducethesenontariff impediments in 1979, whichledto a

dramaticsurgeintrade(figure 4). In 1978 external tradewasmonopolized bya sin-

glegovernment ministry.1Specific measuresadoptedin Chinaincludedallowinga

growing number offirms,including privateones,totradedirectly andopeninga for-

eignexchangemarket tofacilitate

thistrade.

Anothermajorimpediment to trade inmanydeveloping areasis inefficient

ports

andcustomsadministration. Forexample, itis muchmoreexpensive toshipa con-

taineroftextiles

from a Mombasa,Kenya,porttotheEastCoastoftheUnitedStates

DavidDollar 151

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Tariff

Figure3. AverageUnweighted Rates,byRegion,1980-98 (%)

^^

|=31986"90

1980-85

EU 1991-95

South Latin

AmericaEastAsia Sub- Middle

EastandEuropeand Industrialize

Asia andthe andthe Saharan North

Africa Central economies

Caribbean Pacific Africa Asia

Source:WorldBank (2002).

andVolumesinChina,1978-2000

Figure4. TradeReforms

Trade/GDP

(log) tariff

Average

201 V '5

^ rate

tariff

Average

1.6- . ^ / "-4

^- **'^'/

1.2- Trade/GDP^ ^/ ! ' . 0.3

j

0.8 - I | 'i988 8,000trading

companies' 0.2

j

! ! ! 1986 Foreignexchangeswapmarket

j

' i '1984 800trading

companies

0.4- ! ! i -1

! !1979 Openspecialeconomiczones toFDI,foreign

exchangeretention

M i i i

i1978 Trade monopolized fForeignEconomicRelationsand Trade

byMinistry

0-4- i- , , i 1 ' , , , . . r-L0

1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000

Source:Dollarand Kraay(2003).

152 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 {Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

thanfrom Asianportssuchas Mumbai,Shanghai,Bangkok, orKaohsiung, Taiwan

(China),even though Mombasa is closer (Clarkand others2004). The extra cost,

equivalentto an 8 percent exporttax,is duetoinefficiencies andcorruption in the

port.Long customs delays often

act as and

import export taxes. Developing econo-

miesthathavebecomemoreintegrated withtheworldeconomyhavereasonably

well-functioningportsandcustoms, andtheirimprovement has oftenbeena delib-

eratepolicytarget.Severalcountries, includingKenya,tradelessoftheirincome

today than 20 yearsago; this

surely is the

partly tradepolicies,

resultofrestrictive

definedbroadly toinclude inefficient

ports and customs.

Thus,one keydevelopment in thiscurrent wave ofglobalizationis a dramatic

change inthewaymanydeveloping countries relate

tothe globaleconomy. Developing

economies as a wholearea majorexporter ofmanufactures - manyof

and services

whichcompete withproducts

directly madeinindustrialized Thenatureof

countries.

tradeandcompetition between richandpoorcountries hasfundamentally changed.

AcceleratedGrowth Reduction

and Poverty

in DevelopingEconomies

Someofthedebateaboutglobalization concernsitseffectson poorcountries and

poorpeople.The introductionquotes severalsweeping statementsthat assertthat

globaleconomicintegrationis increasing

poverty and inequalityin theworld.But

-

isfarmorecomplex andtosomeextent

thereality runsexactlycounter towhatis

beingclaimed Thus,

byantiglobalists. thissectionfocuseson the trends in global

poverty and thefollowing

and inequality, sectionlinksthemto globalintegration.

Thetrendsofthelast20 yearshighlightedhereare:

Growth ratesofdeveloping economieshave accelerated and are higherthan

thoseofindustrializedcountries.

Thenumberofextremely poorpeople(thoselivingon lessthan$1 a day)has

declinedforthetimeinhistory, thoughthenumber ofpeoplelivingon lessthan

$2 a dayhasincreased.

Measuresofglobalinequality havedeclined

(suchas theglobalGinicoefficient)

modestly, a

reversinglong trend

historical toward greaterinequality.

Within-country ingeneralisnotgrowing,

inequality thoughithasriseninsev-

eralpopulouscountries (China,India,theUnitedStates).

Wageinequality in generalhas beenrising(meaninglargerwageincreases for

skilled

workers thanforunskilled workers).

Thefifthtrendmayseemtoruncountertothefourth trend;whyitdoesnotwillbe

explainedhere.

The fifth

trend is for

important explaining about

someoftheanxiety

in

globalization industrialized

countries.

DavidDollar 153

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ratesin Developing

Growth HaveAccelerated

Economies

Reasonablygooddataoneconomic growth since1960 forabout100 countries that

accountforthevast majority ofworldpopulationare summarized in thePenn

WorldTables(CenterforInternational Comparisons 2004). Aggregating data on

growth rates

for industrialized

countriesand developingeconomies forwhich there

aredatasince1960 showsthatingeneralgrowth rateshavedeclinedinrichcoun-

trieswhileaccelerating in developingcountries(figure5). In particular,in the

1960s growth ofOECD countrieswas abouttwiceas fastas thatofdeveloping areas.

Percapitagrowth ratesinrichcountrieshavegradually declinedfrom about4 per-

centin the1960s to 1.7 percentin the 1990s- closeto thelong-term historical

trendrateoftheoecdcountries. Therapidgrowthin the 1960s was stillto some

extenta reboundfromthedestruction ofWorldWarII as wellas a payoff to eco-

nomicintegration amongrichcountries.

In the1960s andearly1970s,thegrowth rateofdevelopingeconomies waswell

belowthatofrichcountries, a paradoxwhoseoriginhas beenlongdebated.The

slowergrowthofless developedeconomieswas a paradoxbecauseneoclassical

growth theorysuggested thatotherthingsbeingequalpoorcountries shouldgrow

Figure 5. GDP

perCapitaGrowth Type,1960s-1990s (%)

Rate,byCountry

Industrialized

countries

4 - ^^H

lh

^^^B Developing

1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s

Source:CenterforInternational

Comparisons(2004).

154 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 (Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

faster.

Thispattern finallyemerged inthe1990s,withpercapitagrowth indevelop-

ingcountriesofabout 3.5 percent- morethan twice therateofrichcountries.

Thishighaggregate growth dependsheavilyon severallargecountries thatwere

the

among poorest in the world in 1980 but thathave grown wellsince then.Ignor-

ingdifferencesin population and averaginggrowthratesin poorcountries over

1980-2000 resultin an averagegrowthofaboutzeroforpoorcountries. China,

India,and severalsmallcountries, in Africa,

particularly are amongthepoorest

quintileofcountriesin 1980. Ignoring population, theaveragegrowth ofChadand

Chinais aboutzero,and the averagegrowthofIndia and Togo is aboutzero.

Accounting fordifferences inpopulation,though, theaveragegrowth ofpoorcoun-

trieshasbeenverygoodinthepast20 years.Chinaobviously carriesa largeweight

inanycalculation ofthegrowth ofpoorcountries in 1980,butitisnottheonlypoor

country thatdid well: Bangladesh, India,and Vietnam also grewfasterthanrich

countriesinthesameperiod.SeveralAfrican economies, notablyUganda,alsohad

acceleratedgrowth.

TheNumber PoorPeopleHas Declinedby375 MillionGlobally

ofExtremely

Themostimportant pointinthissection isthatpoverty reduction inlow-income coun-

tries

isveryclosely related tothegdpgrowth rate.Theaccelerated growth oflow-income

countries has ledto unprecedented poverty reduction.Bypoverty I meansubsisting

belowsomeabsolute threshold. Mostpoverty analysesare carried out withcountries'

ownpoverty whicharesetincountry

lines, contextandnaturally differ.

China,forexample,uses a poverty linedefined in constantChineseyuan.The

poverty lineis deemedtheminimum amountnecessary tosubsist.In practice, esti-

matesofthenumber ofpoorin a country suchas Chinacomefrom household sur-

veys carried out by a statisticalbureau. These surveys aim to measure what

households actuallyconsume.Mostextremely poorpeoplein theworldare peas-

ants,and theysubsistto a largeextenton theirown agricultural output.To look

onlyat theirmoneyincomewouldnotbeveryrelevant, becausetheextremely poor

haveonlylimited involvement in themoneyeconomy. Thusmeasuresaskhouse-

holdswhattheyactuallyconsumeandattacha valuetotheirconsumption basedon

thepricesofdifferent commodities. So a poverty lineis meantto capturea certain

reallevelofconsumption. Estimating the extent ofpoverty is obviously subjectto

error,butinmanycountries themeasuresaregoodenoughtopickup largetrends.

In discussing it is

poverty important to be clearon thepoverty linebeingused.In

globaldiscussions international poverty linesofeither$1 day $2 a day,calcu-

a or

latedatpurchasing powerparity, areused.Fordiscussions ofglobalpoverty a common

lineshouldbeappliedtoallcountries.

ChenandRavallion(2004) usedhouseholdsurveydatatoestimate thenumber

ofpoorpeopleworldwide basedon the$1 a dayand $2 a daypoverty linesbackto

DavidDollar 155

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1981. Theyfoundthattheincidence ofextreme poverty (consuming lessthan$1 a

day) was basicallycut in halfin 20 years, from 40.4 percent of thepopulation in

developing economiesin 1981 to 21.1 percent in 2001. It is interestingthatthe

declinein $2 a daypoverty incidence was notas great,from66.7 percent to 52.9

percent,overthesameperiod.

Povertyincidence has beengradually declining throughout modern history, but

in generalpopulation growth has outstripped thedeclinein incidence so thatthe

totalnumber ofpoorpeoplehasactually risen.Evenin 1960-80,a reasonably pros-

perousperiodfordeveloping economies, thenumberofextremely poorpeoplecon-

tinuedto rise(figure6).2Moststriking in thepast20 yearsis thatthenumberof

extremelypoorpeople declined by 3 75 whileatthesametimeworldpopula-

million,

tionroseby1.6 billion.Butthedeclinewas notsteady:in 1987-93 thenumber of

extremelypoorpeople rose, as growth slowed in China and India underwent an eco-

nomiccrisis.

After 1993 growth andpoverty reductionaccelerated inbothcountries.

The1981-2001 declineinthenumber ofextremely poorpeopleisunprecedented

inhumanhistory. Atthesametimemanyofthosewhoroseabovetheverylow$1 a

daythreshold arestilllivingon lessthan$2 a day.Thenumberofpeoplelivingon

lessthan$2 a dayincreased between1981 and2001 bynearly300 million. About

halftheworlspopulation stillliveson lessthan$2 a day,anditwilltakeseveral

moredecadesofsustained growth tobringthisfigure downsignificantly.

Figure6. Extreme intheWorld,1820-2001 (millions

Poverty ofpeoplelivingon lessthan$1

a day)

1,500-j

andMorrisson I

,|4QQ_ Bourguignon

1,300- / ^/ I

1,200- / Y'

1,100- s^ i^

yS ChenandRavallion

1,000- /

900- r

1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000

Source: andMorrisson

Bourguignon (2002);ChenandRavallion

(2004).

156 TheWorld

BankResearch vol.20,no.2 (Fall2005)

Observer,

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Although theoveralldeclinein extreme poverty is positivenews,performance

has variedbyregion.SouthAsiaandEastAsia and Pacificgrewwelland reduced

poverty,butSub-Saharan Africahadnegative growth between1981 and2001 and

a riseinpoverty:

thenumber ofextremely poorpeople there from164 mil-

increased

lion(41.6 percent

ofthepopulation) to316 million(46.9 percent ofthepopulation).

Two-thirds ofextremely

poorpeople still

liveinAsia,but ifstronggrowththerecon-

tinues, willbeincreasingly

globalpoverty concentrated inAfrica.

GlobalInequalityHas DeclinedModestly

Globalinequality is casuallyusedtomeanseveralthings, butthemostsensibledefi-

nitionis thesame as fora country: lineup all thepeoplein theworldfromthe

poorest to the richest and calculatea measureofinequality amongtheirincomes.

Thereareseveralmeasures, ofwhichtheGinicoefficient is thebestknown.Bhalla

(2002) estimates that the globalGini coefficientdeclined from0.67 in 1980 to

0.64 in 2000 afterrisingfrom0.64 in 1960. Sala-i-Martin (2002) likewisefinds

thatall thestandardmeasuresofinequalityshowa declinein globalinequality

since1980. BothBhalla and Sala-i-Martin combinenationalaccountsdata on

incomeor consumption withsurvey-based data on distribution. Deaton(2004)

discussestheproblems ofusingnationalaccountsdata forstudying poverty and

inequality, notingamongotherthingsthatthegrowth ratesin nationalaccounts

data forChinaand India are arguablyoverestimated. Thisbias wouldtendto

exaggerate thedeclineinglobalinequality overthepast25 years.Hence,thereis a

fairdegreeofuncertainty aboutthemagnitude oftheestimated declinein global

inequality.3

Forhistoricalperspective, Bourguignon and Morrisson(2002) calculatethe

global Gini coefficient back to 1820. Althoughconfidence in theseearlyesti-

matesis nothigh,theyillustrate an important point:globalinequalityhas been

on therisethroughout moderneconomichistory. Bourguignon and Morrisson

estimatethattheglobalGinicoefficient rosefrom0.50 in 1820 to about0.65

around1980 (figure7). Sala-i-Martin (2002) estimates thatithas sincedeclined

to0.61.

Othermeasures ofinequality suchas meanlogdeviation showa similar trend,ris-

ing untilabout 1980 and then declining after

modestly (figure 8). Roughlyspeak-

ing,themeanlogdeviation isthepercent differencebetweenaverageincomeinthe

worldandtheincomeofa randomly chosenindividual whorepresents a typical

per-

son.Averagepercapitaincomeintheworldtodayis around$5,000,butthetypical

personliveson 20 percent ofthat,or$1,000. Theadvantageofthemeanlogdevia-

tionis thatitcan be decomposed intoinequality betweencountries in

(differences

percapitaincomeacrosscountries) andinequality withincountries. Thisdecompo-

sitionshowsthatmostinequality intheworldcanbe attributed toinequalityamong

DavidDollar 157

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Figure7. GlobalGiniCoefficient,

1820-1997

0.70-

0.65- -~- -*-* *"

0.60- /"

/ Bourguignon-Morrisson Sala-i-Martin

0.55- y/

0.50- S

0.45-

0.40-1] , , , , , , , , ,

1820 1850 1880 1910 1940 1970 1976 1982 1988 1994

Source:Bourguignonand Morrisson(2002); Sala-i-Martin

(2002).

countries.Globalinequality rosefrom1820 to 1980, primarily becausealready

richcountries

relatively (thoseinEuropeandNorthAmerica)grewfaster thanpoor

ones.As notedin the discussionofthe firsttrend,thatpatternof growthwas

reversedstarting around1980, and thefastergrowthin suchpoorcountries as

Bangladesh, China,India, and Vietnam accounts for the modest declinein global

inequalitysincethen.4(Slowgrowth in Africatendedtoincreaseinequality, faster

growth in low-income Asia tended to reduce it, and Asia's growth modestly out-

weighed Africa's.)

Thinking aboutthedifferent experiences ofAfrica andAsia,as inthelastsection,

helpsgive a clearerpicture ofwhat is likely happeninthefuture.

to Rapidgrowth in

Asiahasbeena force forgreater globalequality becausethatiswherethemajority of

theworld'sextremely poorpeople lived in 1980 - and they benefitedfrom growth.

Butifthesamegrowth trends persist, theywillnotcontinue tobe a forceforequal-

ity.Sala-i-Martin (2002) projectsfutureglobalinequality ifthe growthratesof

1980-98 persist: globalinequality will continue to decline untilabout2015, after

whichglobalinequality willrisesharply (seefigure 8). A largeshareoftheworld's

poorpeople still

lives in India and other Asian countries, so thatcontinued rapid

growth therewillbe equalizing foranotherdecadeorso. Butincreasingly poverty

willbeconcentrated inAfrica, so thatifslowgrowth persists there,globalinequality

willeventually riseagain.

158 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 {Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Figure8. GlobalHouseholdInequality,

1820-2050 (meanlogdeviation)

1.2-1

1.0- /

0.8- Sala-i-Martin y^

^^^X^^^

0.6-

/

>^ Bourguignon-Morrisson

0.4-

0.2-

0.0[- ,,,,,, , , , , , , , , , , ,

1820 1986 1994 2001 2010 2018 2026 2034 2042 2050

1978

185O87189O91%2995197O

Source: Bourguignon and Morrisson (2002); Sala-i-Martin (2002).

InequalityIs in GeneralNot Growing

Within-Country

Theprevious analysisshowsthatinequality withincountries small

has a relatively

rolein measuresofglobalincomeinequality. Butpeoplecareabouttrendsin ine-

qualityintheirownsocieties(arguably morethantheycareaboutglobalinequality

and poverty). question whatis happeningto incomeinequality

So a different is

withincountries.Onecommonclaimaboutglobalization is thatitleadsto greater

inequalitywithincountries

and thus fosters

social

and polarization.

political

To assessthisclaimDollarandKraay(2002) collected incomedistribution data

frommorethan100 countries, in somecasesgoingbackdecades.Theyfoundno

generaltrendtowardhigherorlowerinequality withincountries. Focusingon the

shareofincomegoingtothebottom anothercommonmeasureofinequal-

quintile,

ity,theyfound in

increases inequality forsome countries(forexample,Chinaand

theUnitedStates)inthe1980s and 1990s anddecreasesforothers. Theyalsotried

to use measuresof integration to explainthe changesin inequalitythathave

occurred,butnoneofthechangeswererelatedtoanyofthemeasures. Forexample,

countriesin whichtradeintegration increasedshowedrisesin inequality in some

DavidDollar 159

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

cases and declinesin others(figure9). Theyfoundthe same resultsforother

measures, suchas tariff ratesandcapitalcontrols. Particularly inlow-income coun-

muchoftheimport

tries, protection benefited rich

relatively and powerful groups,so

thatintegration withtheglobalmarket wenthandinhandwithdeclines inincome

inequality.It is widelyrecognized thatincomedistribution datahavea lotofmea-

surement error,whichmakesit difficult to identifysystematic relationships,but

giventheavailabledata,thereis no robustevidencethatintegration is systemati-

callyrelatedto higher inequality within countries.

Therearetwoimportant caveatstothisconclusion. First,inequality has risenin

severalverypopulouscountries, notably China, India,and the United States.This

meansthata majority ofcitizensoftheworldliveincountries inwhichinequality is

rising.Second, thepicture of inequality is not so favorablefor richcountriesin the

past decade. The Luxembourg IncomeStudy,using comparable, high-quality

incomedistribution dataformostrichcountries, findsno obvioustrends ininequal-

itythrough the mid-to late 1980s. Over the pastdecade,through, inequality has

increasedinmostrichcountries. Becauselow-skilled workers inthesecountries now

compete more with workers in developing economies, global economic integration

can createpressure forhigherinequality in richcountries whilehavingeffects in

poor countries thatoften go the other way. The good news from the Luxembourg

IncomeStudyisthat"domestic policiesandinstitutions stillhavelargeeffects onthe

levelandtrendofinequality withinrichandmiddle-income nations, evenin a glo-

balizingworld Globalization doesnotforceanysingleoutcomeon anycountry"

Figure9. Correlation

betweenChangeinGiniCoefficient

andChangeinTradeas a Shareofgdp

15-

*

*

-.;.

5U;a %%**

s

*.'' * *

i

* *

%

-10-

-15-

Chanae in trade to GDP

Source:Dollarand Kraay(2002).

160 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 (Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

(Smeeding 2002, p. 179). In otherwords,somerichcountrieshave maintained

stableincomedistributionsinthiseraofglobalization

through socialandeco-

their

nomicpolicies(ontaxes,education, andthelike).

welfare,

WageInequalityIs RisingWorldwide

Much of the concernabout globalization in richcountriesrelatesto workers,

wages,and otherlabor The

issues. most comprehensive examination ofglobaliza-

tionand wages used International Labour Organization data from the pasttwo

decades(Freemanand others2001). Thesedata lookacrosscountries at whatis

to for

happening wages veryspecific occupations (forexample, bricklayer,primary

schoolteacher,nurse,autoworker). The studyfoundthatwages have generally

been risingfastestin moreglobalizeddevelopingeconomies,followedby rich

andthenlessglobalized

countries, developingeconomies(figure 10). Moreglobal-

izeddeveloping economiesare thetopthirdofdeveloping economiesin termsof

increasedtradeintegration overthepast20 years(Dollarand Kraay2004). Less

globalizeddeveloping economiesare the remaining developing economies.The

fastestwage growthis occurringin developingeconomiesthat are actively

increasingtheirintegrationwiththeglobaleconomy.

Although general in wagesis goodnews,thedetailed

the rise findingsfrom Free-

manandothers(2001) aremorecomplex andindicate thatcertain typesofworkers

morethanothers.

benefit First,increasedtradeis relatedto a declinein thegender

Figure 10. WageGrowth Type,1980s-1990s (%)

byCountry

30- . .

20-

^^^^^^

10- ^^^^^^H

oJ I 1 ^^^^^^H I

Less globalized Richcountries Moreglobalized

developingcountries countries

developing

Source:Freemanand others(2001).

DavidDollar 161

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

wage gap. Moretradeappearsto lead to a morecompetitive labormarketin which

groupsthathave been traditionally discriminatedagainst women,forexample-

-

fareespeciallywell(Oostendorp 2002). Second,thegainsfromincreasedtradeappear

to be largerforskilledworkers.Thisfinding is consistentwithotherworkshowinga

-

worldwidetrendtowardgreaterwage inequality thatis, a largergap betweenpay

foreducatedworkersand pay forlesseducatedand unskilledworkers.Galbraithand

Liu (2001), forexample,finda worldwidetrendtowardgreaterwage inequality

among industries.Wages in skill-intensive such as aircraftproduction,

industries,

havebeengoingup faster thanwagesin low-skill suchas garments.

industries,

Ifwage inequalityis goingup worldwide, how can incomeinequalitynotbe rising

in mostcountries?Thereare severalreasons.First,in the typicaldevelopingecon-

omywage earnersmake up a small share ofthe population.Even unskilledwage

workersare a relatively elitegroup.Take Vietnam,forexample,a low-incomecoun-

trywitha surveyofthesamerepresentative sampleofhouseholdsearlyin liberaliza-

tion(1993) and fiveyearslater.The majorityofhouseholdsin thecountry(and thus

in the sample) are peasants.The householddata show thatthe priceofthe main

agriculturaloutput(rice) went up dramaticallywhile the priceof the main pur-

chasedinput(fertilizer) actuallywentdown.Bothmovementsare relateddirectly to

globalizationbecause overthe surveyperiodVietnambecame a majorexporterof

rice(raisingitsprice)and a majorimporter offertilizer

fromcheaperproducers(low-

eringitsprice).Poor familiesfaceda muchbiggerwedgebetweenrice'sinputprice

and outputprice,and theirrealincomewentup dramatically (Benjaminand Brandt

2002). So, one ofthe mostimportantforcesactingon incomedistribution in this

low-incomecountryhad nothingto do withwages.

Severalruralhouseholdsalso senta familymemberto a nearbycityto workin a

factory forthefirsttime.In 1989 thetypicalwage in Vietnamesecurrencywas the

equivalentof $9 a month.Today,factoryworkersmakingcontractshoes forU.S.

brandsoftenmake $50 a monthor more. So the wage fora relativelyunskilled

workerhas gone up nearlyfivefold. But wages forsome skilledoccupations,for

example,computerprogrammers and Englishinterpreters,may have gone up 10

timesormore(Glewweand others2004). Thus,a carefulstudyofwage inequalityis

likelyto showrisinginequality.Buthow wage inequalitytranslatesintohousehold

inequalityis verycomplex.For a surplusworkerfroma largeruralhouseholdwho

obtainsa newlycreatedjob in a shoe factory, earningsincreasefrom$0 to $50 a

month.Ifmany new wage jobs are created,and iftheytypicallypay much more

than peopleearn in the ruralor informalsectors,a countrycan have risingwage

inequalitybut stableor even decliningincomeinequality.(The Ginicoefficient for

household income inequalityin Vietnam actually declinedbetween 1993 and

1998, accordingto Glewwe2004b.)

In rich countriesmost household income comes fromwages, but household

incomeinequalityand wage inequalitydo nothave to movein thesame direction. If

162 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 {Fall2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

thereare changesin theway thatpeoplepartnerand combineintohouseholds,

household inequalitycanriseevenifwageinequality staysthesame.Another point

aboutwageinequality andhousehold incomeinequality relevant torichcountries is

thatmeasures ofwageinequality areoften madebefore taxesaretakenoutofearn-

ings.Ifthecountry has a strongly progressive incometax,inequality measuresfrom

household data(whichareoftenmadeafter taxesaretakenoutofearnings) do not

havetofollow pretaxwageinequality. Taxpolicycan offset someofthetrends inthe

labormarket.

Finally, households can respondtoincreased wageinequality byinvesting more

in theirchildren's education.A highereconomicreturnto educationis nota bad

as

thing, long as there is equal accessto educationforall. Vietnamsaw a tremen-

dousincreaseinthesecondary schoolenrollment ratein the1990s- from32 per-

centin 1990-91 to 56 percent in 1997-98 (Glewwe2004a). Thisincreasepartly

reflectssociety'sand the government's investment in schools(supported by aid

and

donors) partly reflects households' decisions. Iflittleor no return to education is

perceived (thatis,nojobsattheendoftheroad),itismuchhardertoconvince fami-

liesin poorcountries tosendtheirchildren to school.Wherechildren havedecent

accesstoeducation, a higherskillpremium stimulates a shiftofthelaborforcefrom

low-skilltohigher-skill occupations.

Itshouldalsobenotedthattherehasbeena largedeclineinchildlaborinVietnam

sincethecountry startedintegrating withtheglobalmarket. Thereis ampleevi-

dencethatchildlaboris drivenprimarily bypoverty and educational opportunities.

Childlaboris moreprevalent in poorhouseholds, butbetween1993 and 1998 it

declinedforall incomegroups(figure 11). The changeresulted fromthefactthat

everyone was richerthan they were fiveyears earlier and from theexpansionof

schooling opportunities.

Fromthisdiscussion ofwagetrends, itiseasytoseewhysomelaborunionsinrich

countries areconcerned aboutintegration withdeveloping economies. Itisdifficultto

that is

prove integrationincreasing wageinequality, but itseems that

likely integration

isonefactor. Concerning theimmigration sideofintegration, Borjasandothers (1997)

estimate thatflowsofunskilled laborintotheUnitedStateshavereducedwagesfor

unskilled laborby5 percent from wheretheyotherwise wouldbe.Immigrants whofind

newjobsearnmuchmorethantheydidbefore (10 timesas much,according toWorld

Bank 2002), but theircompetition reducesthe wages of U.S. workersalready

doingsuchjobs.Similarly, imports ofgarments andfootwear from countries suchas

Bangladesh and Vietnam create jobs forworkers that pay far more than other opportu-

nitiesinthosecountries butputpressure onunskilled wagesinrichcountries.

Thusoveralltheeraofglobalization hasseenunprecedented reduction ofextreme

poverty and a modest decline in globalinequality. But ithas put realpressure onless

skilledworkers -

inrichcountriesa keyreasonwhythegrowing integration iscon-

troversial inindustrialized countries.

DavidDollar 163

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LevelsinVietnam,1993 and 1998

Figure11. ChildLaborandHouseholdConsumption

40%-

^^

ono/ '' N. /WW

30%-

^^^"Sv ^^4^

20%- ' 1998

6.54 6.64 6.74 6.84 6.94 7.04 7.14 7.24 7.34 7.44 7.54

Percapitahousehold 1993(logscale)

consumption

Source:Edmonds(2001).

Is Therea LinkbetweenIntegration Reduction?

and Poverty

To keeptrackofthewiderangeofexplanations thatareoffered

forpersist-

entpoverty in developing nations,it helpsto keeptwoextreme viewsin

mind.Thefirstisbasedonan objectgap:Nationsarepoorbecausetheylack

roads,and rawmaterials.

valuableobjectslikefactories, Thesecondview

invokesan idea gap:Nationsare poorbecausetheircitizens do nothave

accesstotheideasthatareusedinindustrial nationstogenerateeconomic

value. . .

Eachgapimparts a distinctive

thrust totheanalysisofdevelopment policy.

The notionof an objectgap highlights savingand accumulation. The

notionofan idea gap directsattention to thepatterns and

ofinteraction

communication between a developing country andtherestoftheworld.

-Paul Romer(1993)

Developingeconomieshavebecomemoreintegrated withtheglobaleconomy in

thepasttwodecades,andgrowth andpoverty

reduction A natural

haveaccelerated.

questioniswhether

thereis a linkbetween

thetwo.In otherwords,couldcountries

164 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 (Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

suchas Bangladesh, China,India,and Vietnamhavegrownas rapidly iftheyhad

remained to

as closed foreign trade and investment as theywere in 1980?Thiscan-

notbe answered withscientificcertainty,butseveraldifferent typesofevidencecan

bebrought tobearonit.

Itisusefultobeginwithwhattoexpectfrom economictheory. As thequotefrom

Romersuggests, traditional growth theory focuses on accumulation andthe"object

gap"between poorcountries andrichones.Ifincreasing thenumber offactories

and

workplaces is the onlyimportant action, it does not matterwhether theenviron-

mentisclosedordominated bythestate.Thismodelwas followed intheextreme by

Chinaand theSovietUnion,and to a lesserextentbymostdeveloping economies,

whichfollowedimport-substituting industrialization strategiesthroughout the

1960s and 1970s.Thedisappointing results from thisapproachledtonewthinking

in

bypolicymakersdeveloping areas and economists studyinggrowth. Romerwas

one ofthepioneersofthenew growththeorythatemphasized how innovation

occursand is spreadand theroleoftechnological advancein improving thestan-

dardofliving.Different -

aspectsofintegrationsendingstudents abroadto study,

connecting to the Internet,allowing foreign firms toopenplants, purchasingthelat-

estequipment and components - can helpovercome the"ideagap"thatseparates

poorcountries from richcountries.

Whatis theevidenceon integration spurring growth? Someofthemostcompel-

lingevidencecomesfrom case studiesthatshowhowthisprocesscan workinpar-

ticularcountries. Amongthecountries thatwereverypoorin 1980, China,India,

Uganda,andVietnam providean interesting rangeofexamples:

China

China'sinitialreforms in thelate 1970s focusedon the agricultural sectorand

emphasized strengthening propertyrights,

liberalizing and

prices, creating internal

markets.Liberalizingforeign tradeand investment werealso partof the initial

reform and an

program played increasingly important rolein growth as the1980s

proceeded(seefigure4). Theroleofinternational

linksisdescribedina casestudyby

Eckaus(1997, pp.415-37):

China'sforeigntradebegantoexpandrapidly as theturmoil createdbythe

CulturalRevolution and newleaderscametopower.Thoughit

dissipated

wasnotdonewithout theargument

controversy, thatopeningoftheecon-

to

omy foreign tradewas necessaryto obtainnew capitalequipment and

new technology was made officialpolicy Mostobviously, enterprises

createdbyforeigninvestors

havebeenexemptfrom theforeigntradeplan-

ningand controlmechanisms. In addition,

substantialamountsofother

typesoftrade,particularly

thetradeofthetownship andvillageenterprises

DavidDollar 165

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

andprivate havebeenrelatively

firms, free.Theexpansion

ofChina'spar-

in

ticipation international

tradesincethebeginningofthereform

move-

mentin 1978, has been one of the mostremarkable featuresof its

remarkabletransformation.

India

ItiswellknownthatIndiapursuedan inward-oriented intothe1980swith

strategy

disappointingresultsin growthand povertyreduction.

Bhagwati(1992, p. 48)

states

crisply the main and

problems failures

of thestrategy:

I woulddividethemintothreemajorgroups:extensive con-

bureaucratic

trolsoverproduction,

investment tradeandfor-

andtrade;inward-looking

eigninvestment and

policies; a substantial goingwellbeyond

sector,

public

theconventionalconfines and

ofpublicutilities infrastructure.

UnderthispolicyregimeIndia'sgrowthin the1960s (1.4 percenta year)and

was disappointing.

1970s (-0.3 percent) Duringthe1980s India'seconomic perfor-

manceimproved, butthissurgewas fueledbydeficit and

spending borrowing from

abroadthatwasunsustainable.Infact,

thespendingspreeledtoa fiscal

andbalanceof

payments crisis

that a

broughtnew, reform to

governmentpower in 1991. Srinivasan

(1996,p. 245) describes

thekeyreform measures

andtheirresults:

In July1991, thegovernment announceda seriesoffarreaching reforms.

Theseincludedan initialdevaluation oftherupeeandsubsequent market

determination ofitsexchangerate,abolition ofimport licensing withthe

important exceptions thatthe restrictions

on imports of manufactured con-

sumergoodsandonforeign tradeinagricultureremained inplace,convert-

(with

ibility some notableexceptions) oftherupee on the current account;

reduction in thenumberoftariff linesas wellas tariffrates;reduction in

excisedutieson a numberofcommodities; somelimited reforms ofdirect

taxes;abolition ofindustriallicensingexceptforinvestment in a few indus-

triesforlocational reasonsorforenvironmental considerations, relaxation

ofrestrictionsonlargeindustrial housesundertheMonopolies andRestric-

tiveTradePractices(mrtp) Act;easingofentryrequirements (including

equityparticipation) fordirectforeign investment; and allowingprivate

investment insomeindustries hithertoreservedforpublicsectorinvestment.

In general,

Indiahas seengoodresultsfrom itsreform withpercapita

program,

incomegrowth a yearinthe1990s.Growth

above4 percent andpoverty reduction

havebeenparticularly in

strong states

thathave made themost liberalizing

progress

theregulatoryframework andprovidinga goodenvironmentfordeliveryofinfra-

structure

services(Goswamiandothers2002).

166 vol.20, no.2 (Fall 2005)

TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Uganda

Ugandahas beenone ofthemostsuccessful in Africaduringthisrecent

reformers

waveofglobalization,

anditsexperiencehasinteresting

parallelswithVietnam's.It,

too,was a countrythatwas quiteisolatedeconomically in theearly

andpolitically

1980s.Theroleoftradereform initslargerreformcontext inCollier

isdescribed and

Reinikka(2001, pp.30-39):

has been centralto Uganda's structuralreform

Trade liberalization

program In 1986 theNRMgovernment inheriteda traderegimethat

includedextensivenontariff biased

barriers, government purchasing, and

highexporttaxes,coupledwithconsiderable smuggling. Thenontariff bar-

riershavegraduallybeenremoved sincetheintroduction in 1991 ofauto-

maticlicensingunderan importcertification scheme.Similarly, central

government purchasingwas reformed andis now to

subject opentendering

withouta preferencefordomestic firmsoverimports The averagereal

GDPgrowth ratewas 6.3 percent peryearduringtheentirerecovery period

(1986-99) and 6.9 percent in the 1990s. The liberalization

oftrade has

had a markedeffecton exportperformance. In the1990s exportvolumes

grew(at constantprices)at an annualized rate of15 percent, and import

volumesgrewat 13 percent. Thevalueofnoncoffee exports increasedfive-

foldbetween1992 and 1999.

Vietnam

Thesamecollection thatcontainsEckaus's(1997) studyofChinaalso has a case

of

study Vietnam, analyzinghowthecountry wentfrombeingone ofthepoorest

countriesin the1980s tobeingoneofthefastestgrowing economiesin the1990s

and

(Dollar Ljunggren 1997,pp.452-55):

ThatVietnamwas ableto growthroughout itsadjustment periodcan be

attributed to thefactthattheeconomywas beingincreasingly openedto

theinternational market. As partofitsoveralleffort

to stabilize

theecon-

omy,thegovernment unifieditsvariouscontrolled

exchangeratesin 1989

anddevaluedtheunified ratetothelevelprevailingintheparallelmarket.

Thiswas tantamount to a 73 percentrealdevaluation;combinedwith

relaxedadministrative procedures forimportsand exports,thissharply

increased theprofitability

ofexporting.

This. . . policyproduced strongincentivesforexportthroughout mostof

the1989-94 period.Duringtheseyearsrealexportgrowth averagedmore

than2 5 percent perannum,andexports werea leadingsectorspurringthe

expansion oftheeconomy. Riceexportswerea majorpartofthissuccessin

DavidDollar 167

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1989; and in 1993-94 therewas a widerangeofexportson therise,

including processed

primary products(e.g.,rubber,cashews,and coffee),

labor-intensive

manufactures,andtouristservices In responsetostabili-

zation,strengthenedproperty and

rights, greater to

openness foreign trade,

domestic savingsincreased

bytwenty percentage pointsofgdp,fromnega-

tivelevelsinthemid-1980sto16 percent ofgdpin 1992.

Are TheseIndividualCountry

FindingsGeneralizable?

Thesecasesprovide persuasive evidencethatopennesstoforeign tradeandinvest-

ment - coupledwithcomplementary reforms- canleadtofaster growth indevelop-

ingeconomies. Butindividual casesalwaysbegthequestion, howgeneralarethese

results?Does the typicaldeveloping economy that liberalizes foreign tradeand

investment getgoodresults? Cross-country statisticalanalysisisusefulforlooking at

thegeneralpatterns in thedata.Cross-country studiesgenerally finda correlation

between tradeandgrowth. To relatethistothediscussion inthefirst section,some

developing economies have had large increases in trade integration (measuredas

theratiooftradetonationalincome),andothershavehad smallincreases oreven

declines.In general, thecountries thathadlargeincreases alsohadaccelerations in

The of

growth. group developing economy globalizers identified by Dollar andKraay

(2004) hadpopulation-weighted percapitagrowth of5 percent inthe1990s,com-

paredwith2 percent inrichcountries and-1 percent forotherdeveloping countries

(figure12). Thisrelationship between tradeandgrowth persists aftercontrollingfor

reversecausalityfromgrowthto tradeand forchangesin otherinstitutions and

policies(DollarandKraay2003).

A third typeofevidence aboutintegration andgrowth comesfrom firm-levelstud-

iesandrelatestotheepigraph from Romer.Developing economies often havelarge

productivity dispersion acrossfirms makingsimilarthings:high-productivity and

low-productivity firms coexist,and in small markets there is ofteninsufficientcom-

petitiontospurinnovation. A consistent findingoffirm-level studiesisthatopenness

leadstolowerproductivity dispersion (Haddad 1993; Haddad and Harrison1993;

Harrison1994). High-cost producers exitthe market as pricesfall;ifthesefirms

werelessproductive orwereexperiencing falling productivity, theirexitsrepresent

productivity for the

improvements industry. Although the destruction andcreation

ofnewfirms is a normalpartofa well-functioning economy, attention is simplytoo

oftenpaidtothedestruction offirms - whichmisseshalfthepicture. Theincreasein

exitsis onlypartoftheadjustment - granted, itis thefirst andmostpainful part-

butiftherearenosignificant barriers toentry,therearealsonewentrants. Theexits

areoften front loaded,butthenetgainsovertimecanbesubstantial.

Wacziarg(1998) uses11 episodesoftradeliberalization inthe1980s toexamine

competition andentry. Usingdataon thenumberofestablishments ineachsector,

168 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 {Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Figure 12. PerCapitagdpGrowth Type,1990s (%,basedongdpinpurchasing

Rates,byCountry

powerparityterms)

6"

4"

2 r^- - 1

*-,'*.''

....

0 1 - 1

^ Richcountries

^^^^^^^H Developing

^^^^^^^^ country

Otherdeveloping globalizers

r*riintrife

Source:Dollarand Kraay(2004).

he calculatesthatentryrateswere20 percenthigherin countries thatliberalized

thanincountries thatdidnot.Thisestimate mayreflect otherpoliciesthataccompa-

niedtradeliberalization,

suchas privatization

andderegulation, so thisislikelytobe

an upperboundoftheimpactoftradeliberalization. However, itis a sizableeffect

and indicatesthatthereis plentyofpotential fornewfirms to respondto thenew

incentives.

Theevidencealsoindicates thatexitratesmaybe significant, butentry

ratesareusuallyofa comparable magnitude. Plant-leveldatafrom Chile,Colombia,

and Moroccospanningseveralyearsin the 1980s whenthesecountries initiated

tradereforms indicatethatexitratesrangefrom6 percent to 11 percent a yearand

entryratesfrom 6 percentto 13 percent. Overtimethe cumulative turnover isquite

witha quartertoa thirdoffirms

impressive, havingturnedoverinfouryears(Rob-

ertsandTybout1996).

The higherturnover offirms is an importantsourceofthedynamicbenefit of

openness.In general,dyingfirms havefallingproductivityand newfirms tendto

increasetheirproductivityovertime(Awand others2000; Liu andTybout1996;

Robertsand Tybout1996). Aw and others(2000) findthatin Taiwan(China)

withina five-year periodthe replacement of low-productivity firmswithnew,

higher-productivity entrantsaccountedfor half or more of the technological

advanceinmanyTaiwaneseindustries.

Although thesestudiesshedsomelightonwhyopeneconomies aremoreinnova-

tiveand dynamic, theyalso showwhyintegration is controversial.Therewillbe

moredislocationinan open,dynamic economy- withsome firms closingandothers

DavidDollar 169

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

startingup.Ifworkershavegoodsocialprotection andopportunities todevelopnew

skills,

everyone canbenefit.Butwithout thesepoliciestherecanbesomebiglosers.

Surveysoftheliterature

on and

openness growth generally findthetotalityofthe

evidencepersuasive.Winters for

(2004, p. F4), example, concludes: "While there

areseriousmethodologicalchallenges anddisagreements aboutthestrength ofthe

evidence,the most plausibleconclusion is thatliberalisationgenerally induces a

temporary (butpossibly increaseingrowth.

long-lived) A majorcomponent ofthisis

an increaseinproductivity." economic

Similarly, historians Lindertand Williamson

(2001, pp. 29-30) sumup thedifferent piecesofevidencelinkingintegration to

growth: "The doubtsthat one can retain about each individualstudy threatento

blockourviewoftheoverallforestofevidence. Eventhoughno onestudycanestab-

lishthatopennessto tradehas unambiguously helpedtherepresentative Third

Worldeconomy, thepreponderance ofevidencesupports thisconclusion."Theygo

ontonotethe"empty set"of"countries thatchosetobelessopentotradeandfactor

flowsinthe1990sthaninthe1960s androseinthegloballiving-standard ranksat

thesametime.As faras we can tell,thereareno anti-global victoriestoreportfor

thepostwar ThirdWorld.Weinfer thatthisisbecausefreer tradestimulatesgrowth

inThirdWorldeconomies today,regardless ofitseffectsbefore1940."

MakingGlobalizationWorkBetterforPoor People

So far,themostrecentwaveofglobalization startingaround1980 hasbeenassoci-

atedwithmorerapidgrowthand poverty reduction in developingeconomiesand

witha modestdeclinein globalinequality. Theseempirical findings froma wide

range of studies

helpexplainwhat otherwise

might appear paradoxical:opinionsur-

veys reveal that is

globalization more in

popular poor countriesthan in richones.In

particular,thePew ResearchCenterforthePeopleand thePress(2003) surveyed

38,000peoplein44 countries inalldevelopingregions.In general,

therewasa pos-

itiveviewofgrowing economic worldwide.

integration Butwhatwas striking inthe

survey was thatviewsof were more

globalization distinctly positive in low-income

countries thaninrichones.

Although mostpeopleexpressed theviewthatgrowing globaltradeandbusiness

tiesare goodfortheircountry, only percent peoplein theUnitedStatesand

28 of

Western Europethought thatsuchintegration was "verygood."Bycontrast, the

sharewhothought was

integration verygood was 64 in

percent Uganda and 56

percent in Vietnam.These countriesstoodoutas particularly but

proglobalization,

respondents fromdeveloping economiesin Asia (37 percent)and Sub-Saharan

Africa(56 percent) werealso farmorelikelyto findintegration "verygood"than

respondents fromrichcountries. a significant

Conversely, minority in

(2 7 percent)

richcountriesthoughtthat "globalization has a bad effect" on theircountry,

170 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 (Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

comparedwitha negligiblenumberofhouseholdsin developingeconomiesin Asia

(9 percent)or Sub-SaharanAfrica(10 percent).

Developingeconomiesalso had a morepositiveviewoftheinstitutions ofglobaliza-

tion.Some 75 percentofhouseholdsin Sub-SaharanAfricathoughtthatmultinational

corporations had a positive

influence on theircountry, comparedwithonly54 percent in

richcountries. Viewsoftheeffect oftheInternational Monetary Fund, theWorld Bank,

and theWorldTradeOrganization (wto)werenearlyas positivein Africa(72 percentof

householdssaidtheyhad a positive effecton theircountry). Bycontrast, only28 percent

ofhouseholdsin Africathoughtthatantiglobalization protestors had a positiveeffect

on

theircountry.Views of the protestors were more positivein the UnitedStatesand

Western 5

Europe(3 percent saidtheprotestors had a positiveeffect

on theircountry).

Althoughglobaleconomicintegration has thepotentialto spurfurther growthand

poverty reduction, whether thispotential is realizeddepends on thepoliciesofdevelop-

ing economiesand the policiesofindustrialized countries.True integration requires

notjusttradeliberalization butalso wide-ranging reforms ofinstitutions and policies,

as thecases ofChinaand Indiaillustrate so clearly.Manyofthecountriesthatare not

participating verymuch in globalizationhave seriousproblemswith the overall

investment climate,forexample,Kenya,Myanmar,Nigeria,and Pakistan.Some of

thesecountriesalso have restrictive policiestowardtrade.But even iftheyliberalize

trade,notmuchis likelytohappenwithoutothermeasures.Itis noteasytopredictthe

reformpaths of thesecountries.(Considerthe relativesuccessescitedhere: China,

India,Uganda,Vietnam.In each case theirreform was a startlingsurprise.)As longas

thereare locationswithweakinstitutions and policies,peoplelivingthereare goingto

fallfurtherbehindtherestoftheworldin termsoflivingstandards.

Buildinga coalitionforreformin theselocationsis not easy,and what outsiders

can do to helpis limited.Butone thingthatindustrialized countriescan do is makeit

easy fordeveloping areas that do choose to open up to join the club of trading

nations.Unfortunately, in recentyearsrichcountrieshave made it harderforpoor

countriesto do so. The GeneralAgreementon Tariffs and Tradewas originallybuilt

aroundagreementsconcerningtradepractices.Now, however,a certaindegreeof

institutionalharmonizationis requiredto join the wto, forexample,on policies

towardintellectualpropertyrights.The proposalto regulatelabor standardsand

environmental standardsthroughwto sanctionswould take thisrequirementfor

institutionalharmonization muchfarther. Developingeconomiessee theproposalto

regulatetheirlabor and environmental standardsthroughwto sanctionsas a new

protectionist toolthatrichcountriescan wieldagainstthem.

Globalizationwillproceedmoresmoothly ifindustrializedcountriesmakeiteasyfor

developing economiesto have access to theirmarkets.Reciprocaltradeliberalizations

haveworkedwellthroughout thepostwarperiod.Therestillaresignificant protectionsin

OECD countriesagainstagricultural and labor-intensive productsthatare important to

developing economies.It wouldhelpsubstantially to reducetheseprotections. At the

DavidDollar 111

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sametime,developing economieswouldbenefit from openingtheirownmarkets further.

Theyhavea lottogainfrommoretradein services. Also,70 percentofthetariff barriers

thatdeveloping areasfacearefrom otherdeveloping economies.So thereismuchpoten-

tialto expandtradeamongdeveloping areas,iftraderestrictions are furthereased.But

thetrendtousetradeagreements toimposean institutional modelfrom oecdcountrieson

developing economies makes itmore difficult

toreach trade agreements thatbenefitpoor

countries.Thecurrent Doha roundofwtonegotiations istakingup theseissuesofmarket

access,butitremainstobe seenwhether richcountries arewillingtosignificantly

reduce

theirtradebarriersinagriculture andlabor-intensive manufactures.

Anotherreasonto be pessimistic aboutfurther integration ofpooreconomiesand

richones is geography.Thereis no inherentreason why coastal China shouldbe

poor- or southernIndia,orVietnam,or northern Mexico.Theselocationswerehis-

toricallyheldback bymisguidedpolicies, and with policyreform theycan growvery

rapidlyand taketheirnaturalplace in theworldincomedistribution. However,the

same reforms are not goingto have the same effect in Chad and Mali. Some coun-

trieshave poor geographyin the sense that theyare farfrommarketsand have

inherently hightransport costs.Otherlocationsfacechallenginghealthand agricul-

turalproblems.So, itwouldbe naive to thinkthattradeand investment can allevi-

ate povertyin all locations.Much morecould be done withforeignaid targetedto

developingmedicinesformalaria,hiv/aids, and otherhealthproblemsin poorareas

and to buildinginfrastructure and institutions in theselocations.The promisesof

greater aid from Europe and the United States at the MonterreyConferencewere

encouraging,butitremainsto be seen ifthesepromiseswillbe fulfilled.

So integrationofpooreconomieswithrichones has providedmanyopportunities

forpoorpeopleto improvetheirlives.Examplesofthebeneficiaries ofglobalization

can be foundamongChinesefactory workers,Mexicanmigrants, Ugandanfarmers,

and Vietnamesepeasants.Lots ofnonpoorpeoplein developingand industrialized

economiesalikealso benefit, ofcourse.Butmuchofthecurrentdebateaboutglobal-

izationseemsto ignorethefactthatithas providedmanypoorpeoplein developing

economiesunprecedented opportunities. Afterall therhetoricabout globalizationis

strippedaway, many ofthe practicalpolicyquestionscome down to whetherrich

countriesare goingto make it easy or difficult forpoor communitiesthatwant to

integratewiththe worldeconomyto do so. The world'spoor peoplehave a large

stakein how richcountriesanswerthesequestions.

Notes

DavidDollaris countrydirectorforChinaand Mongoliaat theWorldBank;hisemailaddressis ddollar@

worldbank.org. This articlebenefited

fromthe commentsoftwo anonymousrefereesand ofseminar

at universities

participants and thinktanksin Australia,China,India,Europe,and NorthAmerica.

172 TheWorldBankResearchObserver,

vol.20, no.2 {Fall 2005)

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1. The phrasefreetraderefersto a situationin whichtradeis notmonopolizedbythegovernment,

butratheris permitted to privatefirmsand citizensas well- so China began to shiftto a policyoffree

tradein 1979.

toobtainsurvey-based

2. It is difficult estimatesofpovertybefore1980. Bourguignonand Morrisson

(2002) combinewhatsurveydata are availablewithnationalaccountsdata to provideroughestimates

ofpovertysince 1820. The broadtrendis clear:thenumberofpoorpeoplein theworldkeptrisinguntil

about 1980.

3. Bhalla (2002) and Sala-i-Martin(2002) also estimateverylarge reductionsin global poverty

based on the nationalaccountsdata, but Deaton (2004) makes a convincingcase that the survey-

based estimatesfromChen and Ravallion (2004) are a morereliableindicatorofchanges in global

poverty.

4. Milanovic(2002) estimatesan increasein theglobalGinicoefficient fortheshortperiodbetween

1988 and 1993. How can thisbe reconciledwiththeBhalla (2002) and Sala-i-Martin (2002) findings?

Globalinequalityhas declinedoverthepast two decades primarily because poorpeoplein China and

India have seen increasesin theirincomesrelativeto incomesofrichpeople(thatis,oecdpopulations).

As noted,1988-93 was theone periodin thepast20 yearsthatwas notgood forpoorpeoplein China

and India. India had a seriouscrisisand recession,and ruralincomegrowthin Chinawas temporarily

slowed.

References

Aw,B. Y., S. Chung,and M. J.Roberts.2000. "Productivity

and theDecisionto Export:MicroEvidence

fromTaiwan and SouthKorea." WorldBankEconomic Review14(l):65-90.

in Rural Vietnamunder

Benjamin,D., and L. Brandt.2002. "Agricultureand Income Distribution

Economic Reforms:A Tale of Two Regions." Policy Research WorkingPaper. World Bank,

Washington,D.C.

Bhagwati,J.1992. India9 s Economy: TheShackled Giant.Oxford,:

ClarendonPress.

Bhalla,Surjit.2002. ImagineThereIs No Country: Poverty, andGrowth

Inequality, intheEraofGlobalization.

Washington,D.C: Institute ofInternational Economics.

Borjas,G. J.,R. B. Freeman,and L. F. Katz. 1997. "How Much Do Immigrationand TradeAffect

Labor

MarketOutcomes?"Brookings PapersonEconomic 1:1-90.

Activity

Bourguignon,F., and . Morrisson.2002. "Inequalityamong WorldCitizens:1820-1992." American

Economic Review92(4):727-44.

Center for International Comparisons. 2004. Penn World Tables. Philadelphia: Universityof

Pennsylvannia.

Chen,S., and M. Ravallion.2004. "How Have theWorld'sPoorestFaredsincetheEarly1980s?" Policy

ResearchWorkingPaper 3341. WorldBank,Washington,D.C.

Clark,Ximena,David Dollar,and AlejandroMicco. 2004. "PortEfficiency,

MaritimeTransportCosts,

and BilateralTrade."Journal Economics75(2):41 7-50.

ofDevelopment

Collier,P., and R. Reinikka.2001. "Reconstruction

and Liberalization:An Overview."In Uganda's

Recovery: TheRoleofFarmsFirms,andGovernment.Regionaland SectoralStudies.Washington,D.C:

WorldBank.

N. 2000. "Globalizationand Growthin theTwentiethCentury."WorkingPaper 00/44. Inter-

Crafts,

nationalMonetaryFund,Washington,D.C.

Deaton, Angus. 2004. "MeasuringPovertyin a GrowingWorld (or MeasuringGrowthin a Poor

World." PrincetonUniversity,Woodrow Wilson School of Public and InternationalAffairs,

Princeton,N.J.

DavidDollar 173

This content downloaded from 194.214.27.178 on Sat, 11 May 2013 04:46:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Dollar,David, and Aart Kraay. 2002. "GrowthIs Good forthe Poor." JournalofEconomicGrowth

7(3):195-225.

. 2003. "Institutions,

Trade,and Growth."Journal

ofMonetary Economics5O(l):133-62.

. 2004. "Trade,Growth,and Poverty."Economic Journal114(493):F22-F49.