Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Anderson Levy 09

Enviado por

Elena GatoslocosDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Anderson Levy 09

Enviado por

Elena GatoslocosDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CU R RE N T D I R E CT I O NS IN P SYC H OL OGI C AL SC I EN C E

Suppressing Unwanted Memories

Michael C. Anderson1 and Benjamin J. Levy2

1

University of St. Andrews and 2University of Oregon

ABSTRACTWhen reminded of something we would prefer In this article we review recent research on the cognitive and

not to think about, we often try to exclude the unwanted neurobiological mechanisms supporting the suppression of un-

memory from awareness. Recent research indicates that wanted memories, focusing on three points. First, stopping re-

people control unwanted memories by stopping memory trieval engages inhibitory control processes that make it harder

retrieval, using mechanisms similar to those used to stop to recall the avoided memory later on. Second, stopping retrieval

reflexive motor responses. Controlling unwanted memories is accomplished by brain areas similar to those that stop motor

is implemented by the lateral prefrontal cortex, which acts responses, which achieve control by reducing activity in brain

to reduce activity in the hippocampus, thereby impairing structures fundamental to memory. Third, people who engage

retention of those memories. Individual differences in the these brain systems effectively are also more successful at

efficacy of these systems may underlie variation in how well suppressing memories, suggesting that difficulties in managing

people control intrusive memories and adapt in the after- intrusive remindings originate from difficulties in executive

math of trauma. This research supports the existence of an control. Collectively, these findings specify a model of motivated

active forgetting process and establishes a neurocognitive forgetting that is of practical importance in understanding and

model for inquiry into motivated forgetting. aiding those suffering from intrusive memories.

KEYWORDSexecutive control; inhibition; forgetting;

trauma; memory THE NEED FOR RESPONSE OVERRIDE

To most people, forgetting is a human frailty to be overcome. Intrusive memories seem to leap to mind in response to re-

More than we realize, however, forgetting is what we want and minders, despite attempts to avoid those memories. Indeed,

need to do. Sometimes we confront reminders of experiences that retrieval often occurs involuntarily in response to reminders. A

sadden usas when, after a death or a broken relationship, key premise of our research is that controlling unwanted mem-

objects and places evoke memories of the lost person. Other ories builds on mechanisms necessary to stop automatic motor

times, reminders trigger memories that make us angry, anxious, responses. Consider an example of motor stopping. One evening,

ashamed, or afraid. A face may remind us of an argument we the first author accidentally knocked a potted plant off his

regret; an envelope may bring to mind an unpleasant task we are window sill. As his hand darted to catch the falling object, he

avoiding; or an image of the World Trade Center in a movie may realized that the plant was a cactus. Mere centimeters from it, he

elicit upsetting memories of September 11. When confronting stopped himself from catching the cactus. The plant fell and was

these reminders, a familiar reaction often occurs: a flash of ex- ruined, but he was relieved to not be pierced with little needles.

perience and feeling followed rapidly by an attempt to exclude This example illustrates the need to override a strong habitual

the unpleasant memory from awareness. At such times, memory response to a stimulus, which is a basic function of executive

is too effective and must be overcome. Suppressing retrieval control (Fig. 1). Without the capacity to override prepotent re-

shuts out the intrusive memories, restoring control over the di- sponses, we could not adapt behavior to changes in our goals or

rection of thought and our emotional well-being. For veterans of circumstances. We would be slaves to habit and reflex.

Iraq and Afghanistan, victims of Hurricane Katrina, witnesses of How do we keep from being controlled by habitual actions?

terrorism, and countless people experiencing personal traumas, One possibility is that we inhibit undesired actions. By this view,

the day-to-day reality of the need to control intrusive memories when we encounter a stimulus, activation spreads from that cue

is unfortunately all too clear. Forgetting is their goal, and re- to possible responses. Activation can be thought of as the amount

membering, the human frailty. of energy a response has, influencing its accessibility; a re-

sponse will be emitted once it is sufficiently activated. If one

wishes to override the response, one may engage inhibitory

Address correspondence to Michael C. Anderson, MRC Cognition and

Brain Sciences Unit, 15 Chaucer Road, Cambridge, CB2 7EF Eng- control, a subtractive mechanism that reduces the responses

land; e-mail: michael.anderson@mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk. activation. Perhaps we control memories in a similar way. Like

Volume 18Number 4 Copyright r 2009 Association for Psychological Science 189

Suppressing Unwanted Memories

Stimulus 100

95 Think

Baseline

Percent Recalled

No-Think

90

85

80

Prepotent Weaker, Contextually

Response Appropriate Response 75

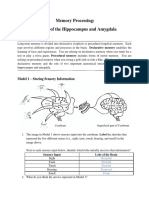

Fig. 1. A typical response-override situation. In such a situation, a stim-

ulus is associated with two responses, one of which is stronger (prepotent) 70

and the other of which is weaker (indicated by the dotted line). Response Same Probe Independent Probe

override occurs whenever one needs either to select the weaker but

more contextually appropriate response or to simply stop the prepotent Type of Final Test

response from occurring. Inhibitory control is thought to achieve response

override by suppressing activation of the prepotent response. This basic Fig. 2. Final recall performance in the think/no-think (TNT) procedure,

situation describes many paradigms in research on executive control, in- aggregating over 687 subjects in many different studies. The graph shows

cluding the go/no-go task. the percentage of items recalled as a function of the whether people thought

of the item (think), suppressed the item (no-think), or had no reminders to

the item during the think/no-think phase (baseline). The left side of the

actions, memories can be triggered by activation spreading from graph shows recall when tested with the originally trained reminder (i.e,

reminders that we encounter. Might inhibition be recruited to the same probe). Interestingly, forgetting for no-think items generalizes

to when their recall is tested with a novel reminder that was not originally

stop retrieval, allowing us to avoid catching our mental cacti? studied (i.e., the independent probe, right side of the graph), such as a

category name for the suppressed response, indicating that the negative

control effect reflects inhibition of the response.

STOPPING RETRIEVAL CAUSES FORGETTING

To study how people stop retrieval, Anderson and Green (2001) ness. Instead, the think/no-think procedure measures the af-

developed a procedure modeled after the go/no-go task, a par- tereffects of stopping retrieval, based on the idea that inhibition

adigm designed to investigate motor stopping. In a typical go/ of the unwanted memory might linger, making these memories

no-go task, participants press a button as quickly as possible harder to recall. To assess this behavioral footprint of suppres-

whenever they see a letter appear on a screen except when the sion, a final test is given in which participants again see each

letter is an X, for which they are to withhold their response. Their reminder and are asked to recall every response they learned

ability to withhold the response measures inhibitory control over earlier. On this test, think items are recalled more often than

action (e.g., how well a person avoids catching the cactus). To see no-think items (Fig. 2). This large difference, known as the

whether stopping retrieval also engages inhibitory control, An- total control effect, demonstrates how the intention to control

derson and Green (2001) adapted this procedure to create the retrieval modulates later memory. Importantly, a third set of pairs

think/no-think paradigm. are studied initially but do not appear during the think/no-think

The think/no-think paradigm mimics situations in which we phase, providing a baseline for measuring both a positive control

stumble upon a reminder to a memory we prefer not to think effect and a negative control effect that contribute to the total

about and try to keep it out of mind. Participants study cue control effect. The positive control effect reflects enhanced

target pairs (e.g., ordealroach), and are trained to recall the memory for think items above baseline recall due to inten-

second word (roach) whenever they encounter the first word tional retrieval, confirming that reminders enhance memory

(ordeal) as a reminder. Participants are then asked to exert when people are inclined to remember. The negative control

control over retrieval during the think/no-think phase. Most effect reflects impaired memory for no-think items below

trials require them to recall the response whenever they see the baseline due to peoples efforts to stop retrieval. When people try

reminder; but for certain reminders, participants are admon- to avoid being reminded, reminders not only fail to enhance

ished to avoid retrieving the response. It is emphasized that it is memory, they trigger inhibitory processes that actually impair

insufficient to avoid saying the responsethey must prevent the memory. The negative control effect is striking and counterin-

memory from entering awareness. Thus, participants have to tuitive, since repeatedly encountering reminders could remind

stop the cognitive act of retrieval. Can people recruit inhibition us of the memory, making it more accessible, not less. The

to prevent the memory from intruding into consciousness? negative control effect occurs even when people are paid for

Since awareness cannot be observed, it is difficult to know each item they remember, making it unlikely that people are

whether a person prevents a memory from entering conscious- simply withholding responses. In contrast, asking people to

190 Volume 18Number 4

Michael C. Anderson and Benjamin J. Levy

merely avoid saying the response, instead of avoiding thinking

about it, eliminates the negative control effect, isolating the

effort to control consciousness as the critical factor causing

Prefrontal Cortex

forgetting.

(Control Area)

Can these processes be engaged to control more complex,

emotional memories? Recent studies indicate that suppressing

retrieval of negative memories causes as great or greater in-

hibition relative to suppressing either neutral stimuli (Depue,

Banich, & Curran, 2006; Depue, Curran, & Banich, 2007) or

positive memories (Joorman, Hertel, Brozovich, & Gotlib,

2005). Moreover, the negative control effect generalizes to

complex scenes (e.g., a car accident; Depue et al., 2007). Thus,

inhibitory control appears effective at suppressing retrieval

of more naturalistic memories, strengthening it as a model

for how people regulate awareness of unpleasant memories in

daily life.

SHUTTING DOWN MEMORY LANE IN THE BRAIN

The preceding sections suggested that people control intrusive Hippocampus

(Memory Area)

memories by engaging systems that suppress overt action. More

direct evidence for this relationship is provided by neuroimaging

studies that assess whether similar brain systems are involved in Fig. 3. A schematic representation of the functional magnetic resonance

stopping retrieval and stopping action. Anderson et al. (2004) imaging (fMRI) results of Anderson et al. (2004). During retrieval sup-

pression (i.e., no-think trials), response-override mechanisms in the

used fMRI to contrast brain activity during no-think and think lateral prefrontal cortex (green area) are engaged to reduce activation in

trials and found that suppressing retrieval recruited a network of the hippocampus (red area, in the cutaway), a structure fundamental

regions including the lateral prefrontal cortex and anterior to memory for events, thereby impairing memory for suppressed items.

Although only the left prefrontal cortex and right hippocampus are illus-

cingulate cortex. This network overlaps strongly with the one trated, these effects occur on both sides of the brain.

involved in motor inhibition tasks (such as go/no-go), even

though no motor responses were required. The lateral prefrontal

cortex, in particular, plays a critical role in stopping reflexive Can emotionally negative memories also be controlled in this

motor responses (e.g., Aron, Fletcher, Bullmore, Sahakian, way? Recently, Depue et al. (2007) replicated the activation of

& Robbins, 2003). In fact, stimulation of this region during a the motor stopping network and the down-regulation of the

go motor response induces monkeys to stop their movement hippocampus during no-think trials when people suppressed

(Sasaki, Gemba, & Tsujimoto, 1989). This overlap suggests that retrieval of aversive scenes. They also found that suppression

stopping unwanted actions and unwanted memories engages a reduced activation in the amygdala, a structure implicated

common neural system. It would be profitable for future studies in emotion processing. This suggests that suppressing recol-

to directly compare memory and motor inhibition areas in the lection of unpleasant memories may also limit negative emo-

same people to confirm colocalization of these functions. tional responses, consistent with the involvement of memory

But how might brain regions involved in suppressing motor suppression in emotion regulation. Importantly, during no-

responses control a memory? The answer lies in the brain region think trials, both the hippocampus and amygdala were not

targeted by control: the hippocampus. The hippocampus is simply less engaged than they were during think trials, they

essential for forming episodic memories (Squire, 1992), and were also less active than they were when people simply stared

increased hippocampal activation has been linked to con- passively at an empty screen, suggesting that overriding re-

sciously recollecting an event. Suppressing an unwanted mem- trieval involves actively disengaging these brain regions.

ory requires that people stop retrieval to prevent conscious It appears that when people want to avoid catching their

recollection. Indeed, hippocampal activity is reduced when mental cacti and prevent an unwelcome reminding, they engage

participants suppress retrieval compared to when they retrieve a systems similar to those necessary for motor stopping. The

memory, suggesting that people can intentionally regulate hip- difference between motor and memory control may be the cor-

pocampal activation to disengage recollection (Anderson et al., tical site influenced by control; with motor inhibition, the motor

2004; Fig. 3). Thus, depending on whether or not people wish to cortex is modulated, but with memory inhibition, people instead

be reminded by a stimulus, they are able to control hippocampal close down memory lane by down-regulating activation in the

activation, influencing retention of that memory. hippocampus (Anderson & Weaver, 2008).

Volume 18Number 4 191

Suppressing Unwanted Memories

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN MEMORY unwanted memories from intruding. Such natural variation in

SUPPRESSION executive control presumably contributes to why some people

are less able than others to control intrusive memories.

The preceding findings suggest that people suppress unwanted What about populations who have difficulties engaging ex-

memories by recruiting the lateral prefrontal cortex to stop re- ecutive control? Theories of cognitive development and aging

trieval, and that doing so makes these memories harder to recall. often focus on how executive-control abilities change across the

Are all people equally effective at this? Perhaps factors known to life span due to the late development and early decline of the

impair executive control, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity prefrontal cortex. Clinically, executive deficits are thought to

disorder (ADHD), damage to the prefrontal cortex, and depres- contribute to psychopathologies including obsessive-compulsive

sion, might render a person vulnerable to intrusive memories. disorder, depression, schizophrenia, ADHD, addiction, and

Such deficits may contribute to persisting flashbacks associated PTSD. Do these populations have impaired memory-control

with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or ruminative ten- abilities? Reduced negative control effects have now been found

dencies evident during depression. Do executive control deficits when older adults are compared to younger adults (Anderson,

cause deficiencies in memory suppression? Reinholz, Kuhl, & Mayr, 2009), when 8- to 9-year-olds are

Imaging and behavioral evidence support this hypothesis. For compared to either 10- to 12-year-olds or adults (Paz-Alonso,

example, brain activity in the lateral prefrontal cortex during Ghetti, Matlen, Anderson, & Bunge, 2009), and when people

no-think trials predicts how much memory suppression each suffering depression are compared to nondepressed controls

person displays (see Fig. 4; Anderson et al., 2004; Depue et al., (Hertel & Gerstle, 2003; but see Joorman et al., 2005). Taken

2007). Electrophysiological measures of brain activity yield together, these findings indicate that the ability to control in-

similar conclusions. Bergstrom, de Fockert, and Richardson- trusive memories develops during childhood and may be vul-

Klavehn (in press) found that individual differences in memory nerable to the effects of normal aging and clinical syndromes

suppression were predicted by the size of an early negative ERP that affect executive function. Thus, elucidating the neurocog-

effect that resembles one associated with performing a no-go nitive mechanisms underlying memory control has the potential

trial and that may originate in the lateral prefrontal cortex. Sim- to impact problems of clinical importance.

ilarly, behavioral measures of executive control, such as complex

working-memory span, predict memory suppression (Bell & CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Anderson, 2005). Indeed, individuals with the poorest working-

memory span showed facilitation of the to-be-suppressed mem- As individuals and as societies, we alter our worlds to prevent

ories, indicating that these participants were unable to prevent ourselves from being reminded of experiences we would prefer

A B

L R 100%

Suppression

Percentage Recalled

6

5 95% Baseline

4

3

2 90%

1

0 85%

+28 +52

80%

75%

1st 2st 3st 4st

DLPFC Activation Quartile

(Suppress>Respond)

Fig. 4. Negative control effect (impaired recall of no-think items relative to baseline items) as predicted by

recruitment of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). Regions plotted in warm colors in (A) are those

that correlated with the magnitude of the negative control effect observed on the final memory tests (the

white arrows indicate the lateral prefrontal cortex). The graph (B) shows the negative control effects for

four subject groups, differing in lateral prefrontal cortex activation. Each quartile in the graph refers to a

group of subjects defined by the degree to which they engaged prefrontal cortex more for no-think trials

compared to think trials. Subjects who showed the largest difference in lateral prefrontal activity (i.e.,

the 4th quartile) showed reduced recall of no-think items compared to subjects who displayed smaller

differences in brain activity. (The groups did not differ in their recall of baseline items.)

192 Volume 18Number 4

Michael C. Anderson and Benjamin J. Levy

not to have had; we throw away photographs and objects given to Recommended Reading

us; we change apartments or towns; we even tear down buildings Anderson, M.C. (2003). Rethinking interference theory: Executive

(e.g., the library associated with the Columbine shooting) to control and the mechanisms of forgetting. Journal of Memory and

Language, 49, 415445. A comprehensive overview of empirical

control what we remember. But reminders are not always es-

findings and theoretical issues related to inhibitory processes in

capable. When forced to live with reminders, our only choice is memory.

to modify our mental landscapeto adapt how our memories Anderson, M.C., & Green, C. (2001). (See References). The original

respond to reminders. In this article, we reviewed work exam- empirical article demonstrating that conscious attempts to prevent

ining how this internal adjustment occurs. People control un- an unwanted memory from entering awareness cause later memory

wanted memories in much the same way they control physical impairment.

actions; they engage neural systems that evolved to inhibit ha- Anderson, M.C., Ochsner, K., Kuhl, B., Cooper, J., Robertson, E.,

Gabrieli, S.W., et al. (2004). (See References). The first neuro-

bitual action, but instead target structures involved in memory. imaging study to show that stopping retrieval is associated with

This inhibition persists, causing these avoided memories to be increased activity in regions involved in motor stopping and de-

harder to remember later. creases in regions associated with successful memory retrieval.

Although the current framework represents a good beginning, Bjork, E.L., & Bjork, R.A. (2003). Intentional forgetting can increase,

significant questions remain (Anderson & Levy, 2006). What is but not decrease, the residual influences of to-be-forgotten infor-

the fate of memories that are suppressed? Are they permanently mation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, &

Cognition, 29, 524531. An illustration of related research with

damaged? Or do they remain in storage, dormant and ready to be the directed forgetting procedure, demonstrating that material

recalled by future reminders? Regardless of the fate of the inhibited in memory may still exert influences outside of aware-

suppressed memory, other remnants of an experience may in- ness.

fluence behavior. Research on multiple memory systems indi- Levy, B.J., & Anderson, M.C. (2008). (See References). A review fo-

cates that emotional conditioning, perceptual priming, and cusing on causes of individual differences in the ability to suppress

procedural skills rely on the amygdala, perceptual neocortex, unwanted memories.

and basal ganglia, respectively (see Squire, 1992, for a review).

If suppressing unwanted memories modulates hippocampal

activity, impairing episodic memories, perhaps conditioning and AcknowledgmentsPreparation of this article was supported

perceptual fluency associated with the experience remain; we by National Science Foundation Grant 0643321.

may fear an object or feel familiarity for a stimulus without

consciously remembering why. At present, little research has

addressed these questions, even though such influences would

REFERENCES

have significant clinical implications. Moreover, other work on

thought suppression has found ironic increases in the accessi- Anderson, M.C., & Green, C. (2001). Suppressing unwanted memories

bility of unwanted thoughts under some conditions (Wenzlaff & by executive control. Nature, 410, 366369.

Wegner, 2000). A complete understanding of how we control Anderson, M.C., & Levy, B.J. (2006). Encouraging the nascent cognitive

unwanted memories requires an account of when control leads to neuroscience of repression. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29,

impaired or enhanced access (see Levy & Anderson, 2008). 511513.

Anderson, M.C., Ochsner, K., Kuhl, B., Cooper, J., Robertson, E.,

For research on memory control to have its greatest impact,

Gabrieli, S.W., et al. (2004). Neural systems underlying the sup-

translational research examining its implications for clinical pression of unwanted memories. Science, 303, 232235.

practice is essential. Do the networks identified here vary in Anderson, M.C., Reinholz, J., Kuhl, B.A., & Mayr, U. (2009). Inten-

efficiency in clinical populations deficient in memory control, tional suppression of unwanted memories grows more difficult as we

such as those suffering from PTSD and ADHD? Can we predict age. Manuscript submitted for publication.

who will experience intrusive memories in the aftermath of Anderson, M.C., & Weaver, C. (2009). Inhibitory control over action and

trauma based on response-override abilities? Can we develop memory. In L. Squire (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Neuroscience,

Volume 5 (pp. 153163). Oxford: Academic Press.

interventions that improve control over unwanted recollections?

Aron, A.R., Fletcher, P.C., Bullmore, E.T., Sahakian, B.J., & Robbins,

Although it may be unwise to ask those suffering from trauma to T.W. (2003). Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right

simply suppress unpleasant memories without coming to grips inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nature Neuroscience, 6, 115116.

with their implications, it would be similarly unwise to ignore the Bell, T.A., & Anderson, M.C. (2005). Keeping things in and out of mind:

need to regulate intrusive memories. Under the best of circum- Individual differences in working memory capacity predict memory

stances, voluntary suppression will not result in a spotless suppression. Manuscript in preparation.

mind, and certainly would not work like a memory-deletion Bergstrom, Z.M., de Fockert, J., & Richardson-Klavehn, A. (in press).

ERP and behavioural evidence for direct suppression of unwanted

device. However, this slower, gradual solution to forgetting may

memories. NeuroImage.

be a graceful compromise between the desire to expel what is Depue, B.E., Banich, M.T., & Curran, T. (2006). Suppression of emo-

unpleasant from our lives and the need to retain experience to tional and non-emotional content in memory: Effects of repetition

grow as individuals. on cognitive control. Psychological Science, 17, 441447.

Volume 18Number 4 193

Suppressing Unwanted Memories

Depue, B.E., Curran, T., & Banich, M.T. (2007). Prefrontal regions or- Paz-Alonso, P.M., Ghetti, S., Matlen, B.J., Anderson, M.C., &

chestrate suppression of emotional memories via a two-phase Bunge, S.A. (2009). Suppressing Unwanted Memories: A Develop-

process. Science, 37, 215219. mental Study. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Hertel, P.T., & Gerstle, M. (2003). Depressive deficits in forgetting. Sasaki, K., Gemba, H., & Tsujimoto, T. (1989). Suppression of visually

Psychological Science, 14, 573578. initiated hand movement by stimulation of the prefrontal cortex in

Joorman, J., Hertel, P.T., Brozovich, F., & Gotlib, I.H. (2005). the monkey. Brain Research, 495, 100107.

Remembering the good, forgetting the bad: Intentional forgetting Squire, L.R. (1992). Memory and the hippocampus: A synthesis from

of emotional material in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psy- findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychological Review,

chology, 114, 640648. 99, 195231.

Levy, B.J., & Anderson, M.C. (2008). Individual differences in sup- Wenzlaff, R.M., & Wegner, D.M. (2000). Thought suppression. Annual

pressing unwanted memories: The executive deficit hypothesis. Review of Psychology, 51, 5991.

Acta Psychologica, 127, 623635.

194 Volume 18Number 4

Você também pode gostar

- Reply Speeches What Are They?Documento2 páginasReply Speeches What Are They?Yan Hao Nam89% (9)

- Neuro-Habits: Rewire Your Brain to Stop Self-Defeating Behaviors and Make the Right Choice Every TimeNo EverandNeuro-Habits: Rewire Your Brain to Stop Self-Defeating Behaviors and Make the Right Choice Every TimeNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)

- Amygdala and HippocampusDocumento8 páginasAmygdala and Hippocampusapi-400575655100% (1)

- Journal of Environmental Psychology - KaplanDocumento14 páginasJournal of Environmental Psychology - KaplanMaría Espinosa100% (1)

- Las Math 2 Q3 Week 1Documento6 páginasLas Math 2 Q3 Week 1Honeyjo Nette100% (7)

- Masgutova MethodDocumento7 páginasMasgutova MethodDisha SolankiAinda não há avaliações

- 555LDocumento8 páginas555LVictor Mamani VargasAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study: Direct Selling ConceptDocumento20 páginasCase Study: Direct Selling Conceptbansi2kk0% (1)

- The Great Psychotherapy Debate PDFDocumento223 páginasThe Great Psychotherapy Debate PDFCasey Lewis100% (9)

- Phelps 2004Documento5 páginasPhelps 2004Alexandra AnghelAinda não há avaliações

- Neuroscience Leadership Management Business Biases PsychologyDocumento13 páginasNeuroscience Leadership Management Business Biases Psychologyjames teboulAinda não há avaliações

- Learning and MemoryDocumento7 páginasLearning and MemoryJacob RosasAinda não há avaliações

- The Intellectual Attributes of Personality: Presented By: Licup, Onalyn S. Miclat, Jennica C. Tinio, Danicadel DDocumento19 páginasThe Intellectual Attributes of Personality: Presented By: Licup, Onalyn S. Miclat, Jennica C. Tinio, Danicadel Dralph macahilig100% (1)

- Inhibitory Control Over Action and MemoryDocumento11 páginasInhibitory Control Over Action and MemoryMaryam TaqaviAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 6 - 7 Study GuideDocumento6 páginasUnit 6 - 7 Study Guideerik19ariasAinda não há avaliações

- Freud's Mental Path To Profits PDFDocumento4 páginasFreud's Mental Path To Profits PDFcepolAinda não há avaliações

- Adaptive Top Activity and The Purging of Intrusive Memories From ConsciousnessDocumento19 páginasAdaptive Top Activity and The Purging of Intrusive Memories From ConsciousnessEszter SzerencsiAinda não há avaliações

- CN Lecture 5 23june21Documento30 páginasCN Lecture 5 23june21SAUMYA MUNDRAAinda não há avaliações

- Memory and ForgettingDocumento5 páginasMemory and ForgettingAreeba asgharAinda não há avaliações

- How The Mind Works Iss10Documento25 páginasHow The Mind Works Iss10elliotAinda não há avaliações

- Psychology Chapter 7: Human MemoryDocumento12 páginasPsychology Chapter 7: Human MemoryNoora Al Shehhi67% (3)

- Tashfiq Ahmed 1811828630 PSY101.13 Mid Term: Short QuestionsDocumento3 páginasTashfiq Ahmed 1811828630 PSY101.13 Mid Term: Short QuestionsTashfiq ShababAinda não há avaliações

- PSYC333 ReadingnotesfromcoursepackDocumento31 páginasPSYC333 ReadingnotesfromcoursepackDavid ChakAinda não há avaliações

- Erasing and Implanting Human MemoryDocumento16 páginasErasing and Implanting Human MemoryMomo PlayerAinda não há avaliações

- The Whiplash SyndromeDocumento17 páginasThe Whiplash SyndromeAbidin ZeinAinda não há avaliações

- Subconscious Mind: Visualization and the Seven Keys to Better ThinkingNo EverandSubconscious Mind: Visualization and the Seven Keys to Better ThinkingNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- DESIMONE, Robert. Neural Mechanisms For Visual Memory and Their Role in AttentionDocumento7 páginasDESIMONE, Robert. Neural Mechanisms For Visual Memory and Their Role in AttentionIncognitum MarisAinda não há avaliações

- Wk2 Paper InfoDocumento5 páginasWk2 Paper InfokellyAinda não há avaliações

- PSYC2650 Exam ReviewDocumento67 páginasPSYC2650 Exam ReviewSaraAinda não há avaliações

- Lec Note PsyDocumento41 páginasLec Note PsyCindy HanAinda não há avaliações

- Cogniiii Chap 6Documento5 páginasCogniiii Chap 6Khayla AcramanAinda não há avaliações

- Mindfulness and Psychology-Mark WilliamsDocumento7 páginasMindfulness and Psychology-Mark WilliamsssanagavAinda não há avaliações

- ABC Elements of SurpriseDocumento5 páginasABC Elements of Surprisemagic77710728406709Ainda não há avaliações

- Negative Priming (Primado Negativo)Documento8 páginasNegative Priming (Primado Negativo)IreneAinda não há avaliações

- 8 Rules for the Messy Mind: How to Understand the Psychological Loop and Get the Most from the Thing Inside Your HeadNo Everand8 Rules for the Messy Mind: How to Understand the Psychological Loop and Get the Most from the Thing Inside Your HeadAinda não há avaliações

- Higher Functions of The Nervous SystemDocumento8 páginasHigher Functions of The Nervous SystemPatterson MachariaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 11 Motor Cognition, Mental StimulationpdfDocumento31 páginasChapter 11 Motor Cognition, Mental StimulationpdfDrew Wilson100% (1)

- Church of Light CC Zain Award 6Documento10 páginasChurch of Light CC Zain Award 6Bolverk DarkeyeAinda não há avaliações

- Reducing RuminationDocumento4 páginasReducing RuminationPhabloDiasAinda não há avaliações

- Edelman, Gerald - Neural DarwinismDocumento8 páginasEdelman, Gerald - Neural DarwinismcdmemfgambAinda não há avaliações

- Psychology PresentationDocumento13 páginasPsychology PresentationUshoshiAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Memory: Memories Like The Corners of My Mind Misty Watercolor Memories of The Way We WereDocumento7 páginasUnderstanding Memory: Memories Like The Corners of My Mind Misty Watercolor Memories of The Way We WereGeorgeta TufisAinda não há avaliações

- MPC 001 G4ewx2 j6qtklDocumento14 páginasMPC 001 G4ewx2 j6qtklParveen Kumar100% (1)

- Human Memory 2024Documento33 páginasHuman Memory 2024ezaat.shalbyAinda não há avaliações

- How To Focus A Wandering MindDocumento5 páginasHow To Focus A Wandering MindSrinivasagopalanAinda não há avaliações

- Mapc 001Documento11 páginasMapc 001Swarnali MitraAinda não há avaliações

- Psychology Module 7.editedDocumento5 páginasPsychology Module 7.editedGeorge Herbert ModyAinda não há avaliações

- W2 BrainDocumento2 páginasW2 BrainEdison KendrickAinda não há avaliações

- Personal DevelopmentDocumento6 páginasPersonal DevelopmentRaizza GomezAinda não há avaliações

- Mindfulness For A Calmer Mind - 993242Documento28 páginasMindfulness For A Calmer Mind - 993242Kat MurrayAinda não há avaliações

- The 12 Pillars of WisdomDocumento6 páginasThe 12 Pillars of WisdomSantiago Montaña LuqueAinda não há avaliações

- Learning and Memomy in Biological PerspectiveDocumento13 páginasLearning and Memomy in Biological PerspectiveTim AroscoAinda não há avaliações

- Solms Scientific Standing of Psychoanalysis 2017Documento5 páginasSolms Scientific Standing of Psychoanalysis 2017Manuel PernetasAinda não há avaliações

- PK Problem Solving ProgramDocumento26 páginasPK Problem Solving ProgramE SfiridakiAinda não há avaliações

- Brain Scanning and The Single MindDocumento4 páginasBrain Scanning and The Single MindJoseph WhiteAinda não há avaliações

- Brain-Centered HazardsDocumento5 páginasBrain-Centered HazardsAhmed Hamdy KhattabAinda não há avaliações

- Neuro-Learning: Principles from the Science of Learning on Information Synthesis, Comprehension, Retention, and Breaking Down Complex SubjectsNo EverandNeuro-Learning: Principles from the Science of Learning on Information Synthesis, Comprehension, Retention, and Breaking Down Complex SubjectsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (2)

- Creativity Sphere - 84Documento5 páginasCreativity Sphere - 84prudhvitapmiAinda não há avaliações

- Imple ON Ssociative EarningDocumento14 páginasImple ON Ssociative EarningWajahat_Mehdi_6547100% (1)

- Memory Game Problem:: Temporal LobeDocumento4 páginasMemory Game Problem:: Temporal LobeDherick RaleighAinda não há avaliações

- Brain DesignDocumento13 páginasBrain DesignNamashree ShahAinda não há avaliações

- Chap#3 Summary Applied EqDocumento4 páginasChap#3 Summary Applied EqHina HussainAinda não há avaliações

- Module 10.11Documento7 páginasModule 10.11Michaella PagaduraAinda não há avaliações

- J Child Neurol 2001 Fennell 58 63Documento6 páginasJ Child Neurol 2001 Fennell 58 63Elena GatoslocosAinda não há avaliações

- Heyes and Catmur Neonatos y Mirror Neurons 2021Documento37 páginasHeyes and Catmur Neonatos y Mirror Neurons 2021Elena GatoslocosAinda não há avaliações

- Bekkali Et Al 2020 Mirror Neuron and Empathy MetaAnalysisDocumento107 páginasBekkali Et Al 2020 Mirror Neuron and Empathy MetaAnalysisElena GatoslocosAinda não há avaliações

- Working Memory Alan Baddeley PDFDocumento4 páginasWorking Memory Alan Baddeley PDFElena GatoslocosAinda não há avaliações

- The MIT Press The Parallel Brain The Cognitive Neuroscience of The Corpus Callosum (Zaidel and Iacoboni, 2003) PDFDocumento568 páginasThe MIT Press The Parallel Brain The Cognitive Neuroscience of The Corpus Callosum (Zaidel and Iacoboni, 2003) PDFElena Gatoslocos100% (1)

- IHE ITI Suppl XDS Metadata UpdateDocumento76 páginasIHE ITI Suppl XDS Metadata UpdateamAinda não há avaliações

- RJSC - Form VII PDFDocumento4 páginasRJSC - Form VII PDFKamruzzaman SheikhAinda não há avaliações

- SLS Ginopol L24 151-21-3-MSDS US-GHSDocumento8 páginasSLS Ginopol L24 151-21-3-MSDS US-GHSRG TAinda não há avaliações

- The Manuals Com Cost Accounting by Matz and Usry 9th Edition Manual Ht4Documento2 páginasThe Manuals Com Cost Accounting by Matz and Usry 9th Edition Manual Ht4shoaib shakilAinda não há avaliações

- Report Web AuditDocumento17 páginasReport Web Auditanupprakash36Ainda não há avaliações

- Automatic Water Level Indicator and Controller by Using ARDUINODocumento10 páginasAutomatic Water Level Indicator and Controller by Using ARDUINOSounds of PeaceAinda não há avaliações

- QinQ Configuration PDFDocumento76 páginasQinQ Configuration PDF_kochalo_100% (1)

- Bernard New PersDocumento12 páginasBernard New PersChandra SekarAinda não há avaliações

- RSC SCST Programme Briefing For Factories enDocumento4 páginasRSC SCST Programme Briefing For Factories enmanikAinda não há avaliações

- Joget Mini Case Studies TelecommunicationDocumento3 páginasJoget Mini Case Studies TelecommunicationavifirmanAinda não há avaliações

- Al-Arafah Islami Bank Limited: Prepared For: Prepared By: MavericksDocumento18 páginasAl-Arafah Islami Bank Limited: Prepared For: Prepared By: MavericksToabur RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- MacDonald, J.& MacDonald, L. (1974)Documento17 páginasMacDonald, J.& MacDonald, L. (1974)Mariuca PopescuAinda não há avaliações

- сестр главы9 PDFDocumento333 páginasсестр главы9 PDFYamikAinda não há avaliações

- Education Under The Philippine RepublicDocumento25 páginasEducation Under The Philippine RepublicShanice Del RosarioAinda não há avaliações

- CLASSIFICATION OF COSTS: Manufacturing: Subhash Sahu (Cs Executive Student of Jaipur Chapter)Documento85 páginasCLASSIFICATION OF COSTS: Manufacturing: Subhash Sahu (Cs Executive Student of Jaipur Chapter)shubhamAinda não há avaliações

- Ring Spinning Machine LR 6/S Specification and Question AnswerDocumento15 páginasRing Spinning Machine LR 6/S Specification and Question AnswerPramod Sonbarse100% (3)

- Raro V ECC & GSISDocumento52 páginasRaro V ECC & GSISTricia SibalAinda não há avaliações

- City Marketing: Pengelolaan Kota Dan WilayahDocumento21 páginasCity Marketing: Pengelolaan Kota Dan WilayahDwi RahmawatiAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1Documento25 páginasChapter 1Aditya PardasaneyAinda não há avaliações

- CAPEX Acquisition ProcessDocumento5 páginasCAPEX Acquisition ProcessRajaIshfaqHussainAinda não há avaliações

- Nonfiction Reading Test The Coliseum: Directions: Read The Following Passage and Answer The Questions That Follow. ReferDocumento3 páginasNonfiction Reading Test The Coliseum: Directions: Read The Following Passage and Answer The Questions That Follow. ReferYamile CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Catalogue 2015-16Documento72 páginasCatalogue 2015-16PopokasAinda não há avaliações

- College Physics Global 10th Edition Young Solutions ManualDocumento25 páginasCollege Physics Global 10th Edition Young Solutions ManualSaraSmithdgyj100% (57)

- Baccolini, Raffaela - CH 8 Finding Utopia in Dystopia Feminism, Memory, Nostalgia and HopeDocumento16 páginasBaccolini, Raffaela - CH 8 Finding Utopia in Dystopia Feminism, Memory, Nostalgia and HopeMelissa de SáAinda não há avaliações

- Problem+Set+ 3+ Spring+2014,+0930Documento8 páginasProblem+Set+ 3+ Spring+2014,+0930jessica_1292Ainda não há avaliações