Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Writing Precis Article Pre Write

Enviado por

api-3231455170 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

28 visualizações6 páginasTítulo original

writing precis article pre write

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

28 visualizações6 páginasWriting Precis Article Pre Write

Enviado por

api-323145517Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 6

Linda E. Martin and Shirley Thacker

Teaching the Writing Process

in Primary Grades

One Teacher’s Approach

“Lreally lke writing ... tis one of my favorite hobbies.”

“lly brain gots more fl of ideas, now that think about it. And

then, all ofa sudden, poof Ihave a gigantic story I can write.”

Statements like these about writing are frequently heard in,

Shirley Thacker’s fst grade classroom, Primary grade teachers

‘who develop a balanced literacy program, rich in literacy and lan-

‘uage experiences that include many writing opportunities, guide

children in @iscoveringshow language works (Clay 2001; McGee &

Richgels 2004; Ray 2004), Programs that include the writing pro-

__cess help children understand thesiigtions and construction of)

mi Cains 1994; Graves 1994; Harwayne 2001; Ray

& Cleaveland 2004), Through the four Stages or tHE Writing prO=) Th

ess rafmgs“editing, and publishing—children begin

to understand the power of becoming an author (Calkins 1994)..

Although much is known about how young children learn to

write (Clay 1980; Temple etal. 1988), many primary grade teachers

have concerns about developing a writing program, Some believe

that learning to write follows learning to read (Elbow 2004). Others

struggle to organize and implement a program that aligns with

their established classroom practices. Thus, itis important for

primary grade teachers who have successfully developed writing

programs to share their knowledge.

is article deseibes how one such teacher, Shirley Thacker

developed and implemented a suecessiul writing program in her

frst grade classroom, whichis known as Thackerville

nolo we

(PeRans Wea are

Linda E Martin, EdD, sa assoc professor nthe Departing ot

Elementary Education at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana. Her UC,

ovearch interests incude primary grado cider’ tracy dovlp-

~y “nent and teachers profesional development eevee.

] shiiey Thacker, NBCT, teaches at WerDel Elementary in Gaston,

Indane teaser for more tna 24 years mn etementry education,

she rocstod er Naonl Bord Certeaton as an Atty Chidrood

15) Generaat n 208 anc er Teach Constant Gaticaon tom the

Indana Witng Projet at Bal Sate Urversy 2007

—/ Seeeatn tiestioned

} rooney Be ‘nol young

FP INAAIEN — Cord dl omotitersiyate

in ne writing oricedou

Thackervil

Entering Thackervile, one hears soft music in the back-

ground. Theres a rug area wil(Glenty of book) Siction and

nonfiction, and a rocking chair forgharing stories}Print

is everywhere, in the fonm of words leamed during vat

us acthities—a Gord wall ons that Piya words that

children’s tories aré postedputside the door.

Shirley works with smal groups ata tale that ean be

seen from ll corners ofthe room. Ina metal cabinet, each

child has a persona le called a story drawer in which

to keep works in progress, Shirley also conducts min

lessons on topics related to writing in various places in the

classroom, using a portable easel that holds chart paper

and a whiteboard. AGariety of resources including ciffer-

ent types of paper as well a tabletop computers and

desketype word processors, are avallable tothe children.

‘The children ofteng nga groups

corGlond}in diferent raserGom, while Shirley

‘works with individuals. The enviconment i€usy But Aue)

for a classroom of 21 first-graders.

If four children wanted to write about

the same topic, they worked together

to create a list of words they could

post in their personal word banks.

Young Children July 2008

Below, and in the pages that follow, Shirley herself

describes how she motivated a classroom of frst-graders to

use the writing process in a workshop format and how this

approach affected the children’s perceptions of writing. She

Includes children’s comments (using pseudonyms).

Analyzing and implementing a

first grade writing program

Children’s writing has always been important to me, but

teaching the writing process was something new. I did not

‘think that first-graders could use the writing process or

reflect independently on their writing. [remembered the

frustration of children in earlier classes when they could not

spell words correctly or understand how to complete their

‘sentences. I viewed this challenge—organizing and imple-

menting a writing program—as an

‘opportunity to learn more about

how children develop writing skill

Creating an environment

for authoring

My frst goal was to create a

classroom environment that invited

shildren to write. made avallablea

Goes

Saez PERE. Pens, colored pencils,

computers with word processing pro

sramenthat the children could choose

from to write and publish thei work.

Tntoduced the children to diferent

authors by reading aloud and diseuss-

ing qualty children’s erature, tion

and nonfiction, o they could understand

how author’ use thelr ideas to share sto-

es and knowledge though wel

he envionment needed to GED

‘Therefore, we collected words and

categorized them ih meaning ways that would help the

children when they wrote: We created a word wall for word

families words ending —ame, —ime, and ake for

narple) to aid in spelling, We sorted words according to

themes to give eiliren new dens for writing topes. The

themes evolved om avarlty of sources—oplcs discussed

intteratue (the ction and nonfiction books we read), on

field trips, ina school assembly, by a guest speaker.

1 collections of words,

related to their writing Topics. Children can gather the

‘words during any type of classroom experience and use

them later in their writing. Children collect words individu-

ally, in small groups, or as a class. For example, if four

children wanted to write about the same topic, they worked

together to create a list of words they could post in their

Methods - est. ery ronment

DUA AINES,

personal word banks. Most of

the words were posted so the aia

children could touch them.

They could trace thelettersin amity Time

the words, which helpedthem Schr generated

remember. This was important

as the children studied words

to add to their waiting.

‘Throughout the year, the

children made connections

between the words they were

earning and how those words

helped them to write. Daryl

explained, “You can just look

around and see a word that you

like, and that gives you an idea

to write about.” In referring to

her personal word bank, Sam

stated, “If forget a word, [know

where Ihave them all" Tony

explained how he used a book he had read (Marc Brown's

Arthur Writes a Story) to help him write a story about

“Arthur: “Imade up the entire story, but [read the book to

‘make me think about how to spell Artur.”

“Guest authors" rom among

‘own work or their favorite iter

Writing Time

Teacher generated

Teacher presents a miniless

Teacher/stucent generated

Children choose to continue:

Establishing routines for young authors

Most of the children in my classroom were just discover-

ing writing, and I wanted to make sure that I had adequate

time for all of them. Therefore, I established basic routines

in the morning for the writing workshop, which lasted

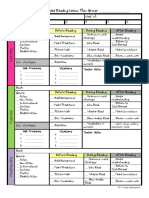

approximately 60 minutes (see the diagram, “Writing

‘Workshop Routines” on p. 34).

Family time. We always began the day with family time,

which the children lead. During that period, “guest authors’

(Children who had published their work) shared their sto-

res with the class. First grade children publish a story by

developing it throygh the writing process, then putting it in

book form to share with others,

Publishing and sharing their work as guest authors was

very important to the children from the beginning. They

wanted to share their published writing with anyone who

‘would listen. They liked publishing their work their own

‘way. Some children preferred to handwrite their story on

special paper, and some liked to publish on the computer.

Some children preferred to handwrite

their story on special paper, and some

ked to publish on the computer.

32

TW nee aertiacy

Teacher models wring a story, and so forth (5 min.)

‘Children write on a aiven topic (5 min.)

‘0r go back to-a work in progress (20 min.)

Family time also included

‘a guest reader—a child who

shared a favorite piece of lit-

erature or her own published

‘work. Having guest writers and

readers share written works

‘with the class helped the chi

dren understand how closely

‘writing and reading relate to

one another.

‘he children share te

ature (20 min.)

0 (10 min) Writing time. Following fam-

lly time, the writing part of the

‘workshop began. I presented

‘a minilesson focusing on an

Important writing behavior,

and then I read aloud a book.

The book might align with a

study topic, ike penguins, or

show how authors develop

stories, Next, the children wrote for five minutes, usually on

atopic of my choice, often related to the book. Afterward,

they could either continue writing on that topic or go back

and write on a work in progress from their story drawer.

In ither task, they followed the basic writing process.

format—plan, write a sloppy copy, edit (by oneself, in peer

conferences, and in a teacher conference), ereate the final

copy, and publish. The process was not linear; children

could revisit a previous stage before moving forward,

writing on the given topic

As the children learned the routines in the writing

‘workshop, I gave them more control—perhaps choosing

their partners themselves or having more time to write.

Eventually, | realized that the writing workshop routines

‘could be nested within any subject throughout the day. As

result, the children learned that as authors, they could

write for a variety of reasons, rfot just to compose a story.

Developing focused mini-lessons

Minilessons (approximately 10 minutes)—short, focused

lessons that held the children's attention—were an impor-

tant part ofthe writing workshop. I selected topics accord

Ing to children's specific needs in developing thelr writing

stalls. usually identified the topics during individual or

soup conferences, from my informal observations while

the children were writing, or by examining their writing

‘samples. For example, I might offer a think-aloud mink

lesson to show children how to stay on topic when writing

‘or how to move forward when they were stuck ona new

word (see “A MinéLesson about Spelling’)

‘When modeling any aspect of writing Livanted the chil

dren to understand that authons'do mae mistakes. This

point became an important component of most ofthe mini

lessons, and the children seemed to absorb the message.

Young Children July 2008

ie

‘Sam stated early in the year, “You just try the hard-

est that you can and do your best. But everybody

makes mistakes.” Daryl explained, “If you don’t know

word, just circle it; put a line under it, and then

ook in the dictionary when you are done.” Susan

reflected on a sentence in one of her stories:

“Mmm .... “Me and my friend go to school...” You

have to put fiend first and you on the end, because

that Is polite. Like, “My friend and me go to school

But we should change me to I”

Children’s writing skills

(and my understanding) grow

Inmany ways,

(Beinstractive for meas itwas for the children.

Young Sa

Thad a difficult time understanding that first

‘grade children can develop their own topics. [knew that

many of the children would struggle to write one word, so

in the beginning I kept the format simple to allow them to

get down their thoughts. For example, | used patterned

stories, such as “I like and the children

filled in a word. Ina few weeks, after various minvlessons

modeling how to develop a topic, they were able to write

‘a sentence or more. By October, those same children were

‘writing on the front and back of the paper. Daryl wrote

about how he gets scared when his mom turns out his light

‘and papers flutter in the wind. When this work was being

published, Daryl reminded me to include the writing on the

back of the sheet,

Pai

eeeeu uss Ii)

Firstgrader think that every word hasto be spt

comedy, and many woud no ry o write new words

unless they had the wor ght in roto them. Often,

frustration about spelling interrupted their flow of ideas

wie wring | wanted he cient think about he

souinds in words and to wrte down atleast the besinning

and ending sous. To help them, t modeled how to write

2 story and thnk outloud about al the sounds in words.

{As lurote my story on the chalkboard, sounded out

the words and prints the coresponding letters. 1 crcled

‘word that didnot look right, so | eau go bak to them

when I rished ving the story. This minitesson showed

‘the young writers that instead of interrupting their train of

oe? thought to come up with an accurate speling, they could

«9 back and corect mistakes lator

WWeDAS- pei

Young Children July 2008

Wiel Saal

Twondered, at first, when | modeled

how to get a story down on paper, whether the children

might copy my story rather than developing thelr own,

However, | ound that the children preferred their own top-

les to mine, Shelly explained, "Sometimes [Mrs. Thacker]

picks topics that not all of us know about, and then that

‘makes the story shorter and not as interesting." Having)

{HOICES|For writing also helped children like John, who

‘struggled with reading and writing. He wrote three pages

about his dad, which he sald was his best work,

Young authorsGevelop plans

‘To help the children understand why planning before writ

ing is important, Ineeded to help them become aware that

‘stories are made up of Orgaiiaeé ne day, picked

upa book that I thought they would enjoy, read one sen-

tence, and then closed the book. When they responded with,

“Hey, that’s not all!" I pointed out that they were writing only

cone or two sentences and calling their work a story. This

lead to a discussion about what a story looks like, and they

‘began to understand that a story includes many elements,

like characters, setting, problem, events, and ending.

Initially, the children dret their plans. Drawing pictures

gave them time to think about the detalls they wanted to

include. | encouraged them tolhare (rehearse) WEI plan,

Capac ask questions that would help them

ough the children learned other ways

To organize thelr ideas (such as webbing), many of them

‘continued to draw pictures, because they felt that draw-

ing presented more details for writing. While developing a

plan about penguins, Kenzi stated, “Right now, that is all

have on my organization, but I might think of more details

wud

sete ‘rng § en

— PLAN, woe Owdli sh

to put in my plan, and then my story will be longer.” Daryl

explained how he used both a picture and mapping to plan,

“because when you get the picture done, ithelps you to

think about what to put on your plan [map]. That helps me

write my story so it makes sense.”

twas common for the children to have more than one

‘work in progress in their file drawer. In some instances, a

child would develop a plan and then move on to another

topic, knowing that she could always return to the plan and

continue to develop it.

Periodically, the children reflected on all

their works in progress. Early on, I doubted

whether many of the children would reflect

‘on their writing and then complete important

pieces, but Iwas wrong. While reflecting on his,

plan for a new story about Peach and Blue, a

book about a talking peach and a blue toad, by

Sarah Kilbome, Daryl said, “Here is the Peach

‘and Blue picture. | started a good one. There

Is the pond over there. Yes, this is a keeper. 1

will write a story from this.” Shelly also began

a story about Peach and Blue: “Yeah, I began a

7 Children Make aneie

story about Peach and Blue. But !haven't written it yet.

have other stories to write, but I will finish it.I think it will,

ea good story.”

‘Young authorg edit their writing

In January Lintroduced the editing process. To begin, I

‘wanted the children to know that authors also have to edit.

‘This was easy to show with the book Difiendoofer, by Dr.

‘Seuss. In the back of the book is the original manuscript,

‘and Dr. Seuss explains how the story evolved throughout

the editing process. I taught the children to first self-edit

and then to select a peer to read the story. The children

used different colored pencils to code each editing stage—

blue for self-ecditing and red for peer editing. To guide the

childzen’s thinking during editing, I developed a checklist of

the writing conventions we had covered thoroughly, such

as using capitals and ending a sentence with a punctua-

tion mark. As the children learned more about writing, the

checklist grew longer.

Making decisions about their writing empowered the

children. Kenzi shared her thoughts on editing: “When you

publish, I think people that are reading [your words] should

know what they are. So, we like to partner edit. The red ink

is with my partner.” Then Kenzi gave an example of how

she helped her partner edit: “Well, [the author] thought the

word snow was okay: So, lasked some questions. Lasked

ithis story had a beginning, an ending, and a middle, and

if there was a big leter at the first of the sentence.” Tony

showed how to stretch words out so his partner could

hear the sounds: "I somebody does not know how to spell

California, then | will help them: Cal--for-ni-a.”

Revising a

previous age

othe wing

oOwK)

Peat uy 2008,

decisions aloud tne irik WO)

Young mana a conference

Holding regular UonTerences both with individuals and

ups of children was very important. I wanted to

‘moving from

helping them, and seeing what they v

ing wershop slowed hehlantomesenospendnti§

3s very used

dee cone fr te wont cheer Crary

‘working through the writing process at their own pace. The

‘ riéeded to bein charge of tier learning. |

"We held small group conferences based on individual

children’s needs, so the groups

of participants changes. For

instance, Lwould hold a confer-

ence with children who needed

help developing complete sen-

tences. When a child was stuck

the writing process, Iheld an

individual conference to help him

In some instances, a

child would develop

a plan and then move

on to another topic,

Dayal aire nua W ici

Mirren ess

Be patient! Learning takes time. Take lime to guide

children through the many different activitios associated

the writing process in the workshop.

iA, such as self-ediing,,

‘such as peer editing, Teachers

‘also need time—to think about how to meet children’s

individual needs as their writing skils develop.

eee eee

children can move from one writing routine to

the next. This may result in a classroom that

looks busy, with students working on thelr indi-

vidual writing samples. Some children may be

(on the floor editing with a peer, working in small

getstarted again.As thechlldren knowing that she groups to develop a topic, examining their writ-

[become mare lndependent; they. ing fle to finish work in progress, sitting on

would at times request aconfer- ould always return

lence with me to work on a spe-

cifie writing problem. To monitor

how often | met with children

and why, [kept a log of the meet-

ings and the topics discussed.

(Gioual and multifaceted in my classroomSpme assessment

‘was child initiated, At the end of every term, the children

reflected on their progress as they examined their work. In

the process, they selected the pieces they wanted to show-

‘case for their parents and other interested parties. The chik

dren, in most cases, wanted to show not only the finished

product but also the drafts that demonstrated the process.

ee

ene SS renee ae

Soe a es

See

ceemee ean

pACIUSID'

Shirley Thacker and her frst-graders demonstrate the im-

portance of.chldren having a vested interest in what and how

‘they learn. Hheyeanirelieet én their progress and can learn

how tomake corrections. Further, they show thal priiary

| rade ehitaren can work collaboratively within their Tearing)

\[environment. In the process, Shirley learned that her chile

‘dren are much more capable than she previously thought.

She said it best: *My instruction has forever changed.”

Cone!

3

Young Chiléren July 2009,

to the plan and con-

tinue to develop it.

‘the carpet reading a story similar to one they

are writing, or writing using a computer. Chik

dren's different locations and groupings show

that they can work independently and are fully

‘engaged in all aspects of the writing process.

Coma aE RATERS ag ad dacssng

Se ere ees

ae ae ee oie eae

Cu orernier tone age reo

eae oa ae ane rca

Surana ne esas eee a eeor

fn lec wing program seuR suppor cos

ge ee eae

See ee

References

Calling, LM. 1994. The ar of teaching writing 2nd ed, Portsmouth, NE:

Heinemann,

‘lay, MIM. 1980, What i Frit? Beginning wring behavior. 3h 6

Portsmouth NE: Heinemann

‘lay, MAM 2001. Change overtime in children’ Iteracy development

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Graves, DH. 1994-4 fesh lol at uring Portsmouth: Ni Heinemann.

Elbow? 2004. Writing rt! Edvcatonal Leadership 62 (2): 8-13.

Harsrayne, 2001, Writing though childhood: Rethinking process and

produc Portsmouth, Ni: Heinemann.

MeGee, LM. &D.JRichgels. 2004 Leracy’s begining: Supporting

‘Young readers and uvters. ith ed. New York Pearson Education.

[Ry KW. with LB. Cleaveland, 2004. About the euthors: Writing work-

‘shop with our youngest unter. Portsmouth, NH: Henemana.

‘Temple. R-Nathan,N. Burrs, F Temple. 1888. Te beginnings of

tuning. 2d, Newton, MA: Alyn & Bacon.

Copy © 2008 by te Nana Assoiaton rhe Eaaton of Youn Citien. See

Perissns and Ress nin t wu naeye ogaboutpermisions 29,

35

Você também pode gostar

- Strategy Resource File FormatDocumento29 páginasStrategy Resource File Formatapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Using Story Impressions To Improve ComprehensionDocumento14 páginasUsing Story Impressions To Improve Comprehensionapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Activity 2 MathDocumento10 páginasActivity 2 Mathapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Guided Reading Lesson Plan: Group - Teacher: Week ofDocumento2 páginasGuided Reading Lesson Plan: Group - Teacher: Week ofapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Spring2spring Funds of KnowledgeDocumento2 páginasSpring2spring Funds of Knowledgeapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Teaching The Writing Process ArticleDocumento7 páginasTeaching The Writing Process Articleapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Writing Samples HighDocumento3 páginasWriting Samples Highapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Final PrecisDocumento1 páginaFinal Precisapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- KwlchartDocumento1 páginaKwlchartapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Rebecca Poem Peer EditDocumento1 páginaRebecca Poem Peer Editapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Final PrecisDocumento1 páginaFinal Precisapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- I Used To But Now I Poem Module 3Documento1 páginaI Used To But Now I Poem Module 3api-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Writing Samples PrimaryDocumento4 páginasWriting Samples Primaryapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Writing Samples MiddleDocumento3 páginasWriting Samples Middleapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Double Entry Journal XDocumento1 páginaDouble Entry Journal Xapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Poem Prewrite and Rough DraftsDocumento5 páginasPoem Prewrite and Rough Draftsapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Teaching The Writing Process ArticleDocumento7 páginasTeaching The Writing Process Articleapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- BiographypostertemplateDocumento5 páginasBiographypostertemplateapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Bio Poem ExampleDocumento1 páginaBio Poem Exampleapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- Addition AcrosticDocumento1 páginaAddition Acrosticapi-323145517Ainda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)