Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Small Stroke Causing Severe Vertigo PDF

Enviado por

DeTe Gun Rap'er ConkK'exsTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Small Stroke Causing Severe Vertigo PDF

Enviado por

DeTe Gun Rap'er ConkK'exsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Small strokes causing severe vertigo

Frequency of false-negative MRIs and nonlacunar mechanisms

Ali S. Saber Tehrani, MD ABSTRACT

Jorge C. Kattah, MD, Objective: Describe characteristics of small strokes causing acute vestibular syndrome (AVS).

FAAN

Methods: Ambispective cross-sectional study of patients with AVS (acute vertigo or dizziness,

Georgios Mantokoudis,

nystagmus, nausea/vomiting, head-motion intolerance, unsteady gait) with at least one stroke risk

MD

factor from 1999 to 2011 at a single stroke referral center. Patients underwent nonquantitative

John H. Pula, MD

HINTS plus examination (head impulse, nystagmus, test-of-skew plus hearing), neuroimaging to

Deepak Nair, MD

confirm diagnoses (97% by MRI), and repeat MRI in those with initially normal imaging but clinical

Ari Blitz, MD

signs of a central lesion. We identified patients with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) strokes

Sarah Ying, MD

#10 mm in axial diameter.

Daniel F. Hanley, MD

David S. Zee, MD Results: Of 190 high-risk AVS presentations (105 strokes), we found small strokes in 15 patients

David E. Newman-Toker, (median age 64 years, range 4185). The most common vestibular structure infarcted was the

MD, PhD inferior cerebellar peduncle (73%); the most common stroke location was the lateral medulla

(60%). Focal neurologic signs were present in only 27%. The HINTS plus battery identified

small strokes with greater sensitivity than early MRI-DWI (100% vs 47%, p , 0.001). False-

Correspondence to negative initial MRIs (648 hours) were more common with small strokes than large strokes (53%

Dr. Newman-Toker: [n 5 8/15] vs 7.8% [n 5 7/90], p , 0.001). Nonlacunar stroke mechanisms were responsible in

toker@jhu.edu

47%, including 6 vertebral artery occlusions or dissections.

Conclusions: Small strokes affecting central vestibular projections can present with isolated AVS.

The HINTS plus hearing battery identifies these patients with greater accuracy than early

MRI-DWI, which is falsely negative in half, up to 48 hours after onset. We found nonlacunar

mechanisms in half, suggesting greater risk than might otherwise be assumed for patients with

such small infarctions. Neurology 2014;83:169173

GLOSSARY

AVS 5 acute vestibular syndrome; DWI 5 diffusion-weighted imaging; ED 5 emergency department; HINTS 5 head impulse,

nystagmus, test-of-skew.

Acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) is a well-defined clinical syndrome1 of continuous vertigo or

dizziness with nausea or vomiting, head-motion intolerance, gait unsteadiness, and nystagmus

lasting days to weeks. AVS constitutes approximately 10% to 20% of emergency department

(ED) dizziness,2 so is responsible for approximately 400,000 to 800,000 US ED visits annu-

ally.2,3 AVS can be caused by peripheral or central lesions. It is estimated that perhaps 25% of

cases are due to stroke.2 Most ischemic stroke patients who present with dizziness or vertigo

present with AVS, but only approximately 20% have focal neurologic signs, while the remainder

have isolated AVS.1,2

Despite extensive ED workups,3,4 diagnostic accuracy in cerebrovascular dizziness is low

(approximately 35% of strokes missed).5 We and others have observed1,6 that very small strokes

sometimes cause AVS; these are often isolated AVS presentations, potentially increasing the chance

of misdiagnosis. We also noted that these patients seemed to have a higher likelihood of false-

negative MRIs, further increasing that risk. There has been no systematic study of whether these

smaller strokes causing AVS differ demographically, mechanistically, or in terms of prognosis.

Supplemental data

at Neurology.org

From the Department of Neurology (A.S.S.T., J.C.K., J.H.P., D.N.), University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria; and Departments of

Neurology (G.M., D.F.H., D.S.Z., D.E.N.-T.) and Radiology (A.B., S.Y.), Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures. Funding information and disclosures deemed relevant by the authors, if any, are provided at the end of the article.

2014 American Academy of Neurology 169

Lesions causing central AVS may be located nonparametric Mann-Whitney test to compare nonnormal distri-

butions of time to MRI. No statistical methods were used to

in the root entry zone of the eighth nerve, ves-

impute missing data, control for confounding, account for sam-

tibular nucleus, nodulus, or flocculus.7 We pling strategy, or conduct sensitivity analyses. The p values

hypothesized that small posterior fossa strokes ,0.05 were considered statistically significant.

causing AVS would mostly involve these struc- Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient

tures and might have a higher initial false- consents. The study was approved by the institutional review

negative MRI rate than larger strokes. We board. Written informed consent was obtained from all partici-

pants. All patients reported here were included in one or more

assessed the frequency, anatomical distribu- prior reports of aggregated study data.1,8,9

tion, clinical manifestations, neuroimaging,

and pathomechanisms of these small strokes. RESULTS Of 190 high-risk AVS presentations, 105

were caused by stroke, all of which were reviewed for

METHODS Patients with AVS who had acute vertigo or dizzi- lesion size. Of these, 14% had lesions #10 mm

ness, nystagmus, nausea or vomiting, head-motion intolerance, (mean age 65.4 years, median 64, range 4185,

and unsteady gait with one or more stroke risk factor were

33% female, 80% Caucasian, 20% African

enrolled in a prospective cross-sectional study from 1999 to

2011 at a single stroke referral center. Study methods have American). Time from onset of symptoms to MRI

been described in detail elsewhere.1,8,9 Briefly, patients were was similar for lesions #10 mm (median 12 hours,

recruited through a combination of passive (investigators interquartile range 648 hours) and .10 mm

notified by emergency care providers) and active (review of (median 12 hours, interquartile range 524 hours)

admitted neurology patients) surveillance. Subjects underwent (Mann Whitney p 5 0.245). Clinicoradiographic

structured bedside examination, including the HINTS battery

case descriptions with lesion loci are shown in table 1.

(head impulse, nystagmus, test-of-skew [table e-1 on the

Neurology Web site at Neurology.org])1 plus bedside hearing

A montage of representative brain MRI sections is

by finger rub (together referred to as HINTS plus).9 Links to presented in figure 1. The most frequently involved

videos demonstrating clinical findings may be found in the vestibular structure was the inferior cerebellar

supplemental data. Examinations generally occurred before peduncle (73%). The most frequently affected

neuroimaging, or examiners were masked to stroke status, location was the lateral medulla (60%); notably,

to minimize observer bias in the determination of clinical

however, two-thirds of these initially presented

examination findings. All underwent neuroimaging to confirm

final diagnoses. For neuroimaging, 97% of patients underwent

with isolated AVS and none presented the

MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (MRI-DWI), while 3% complete Wallenberg syndrome. An isolated

had large infarcts with mass effect evident by CT and were not cerebellar infarction was found in only one case.

clinically stable enough for MRI. Repeat MRI-DWI was obtained Nonoculomotor general neurologic signs were

in patients with normal initial imaging but clinical signs present in only 27% at initial presentation (table 1).

suggestive of a central lesion. Stroke was defined by a DWI-

The HINTS plus battery identified small strokes in

bright lesion in a compatible location without evidence of an

AVS with greater sensitivity than early MRI with

alternative etiology by neuroimaging, as determined by a

neuroradiologist. Stroke was excluded in peripheral patients by DWI (100% vs 47% [n 5 7/15], p , 0.001), even

absence of focal neurologic signs (isolated AVS), negative more so in those with isolated AVS (100% vs 36%

neuroimaging, and clinical follow-up. [n 5 4/11], p , 0.001). False-negative MRIs with

The sample size for this retrospective analysis was based on small strokes occurred 6 to 48 hours after the onset of

availability of relevant patients in our research database. We vestibular symptoms. Anatomical neuroimaging sen-

include here patients with DWI strokes #10 mm in axial diam-

sitivity varied by stroke size (47% small vs 92% large),

eter. The choice of a 10-mm cutoff was intended to focus the

analysis on unequivocally small strokes for 2 reasons: (1) to have despite similar duration of symptoms before MRI,

greater anatomical certainty about the specific vestibular struc- while physiology-based clinical examinations did

tures involved; and (2) to identify lesions that might evoke the not (100% small vs 99% large) (table 2). Head

clinical notion of being somehow unimportant (e.g., presumed to impulse testing was abnormal (erroneously suggesting

have a lacunar mechanism based solely on small size, reducing the a benign peripheral lesion) in 2 pontine cases

likelihood of further mechanistic workup or more aggressive

(patients 11 and 12), but the presence of other signs

stroke therapies). The axial diameter of strokes with a lacunar

pathomechanism is highly variable, because the shape of lacunar

(direction-changing nystagmus and skew in patient

strokes is often irregular,10 so the choice of 10 mm as opposed to 11, and hearing loss and facial palsy in patient 12)

some other specific diameter was somewhat arbitrary. correctly localized the lesion. Nonlacunar stroke

Anatomical stroke loci were confirmed by 2 experts in posterior mechanisms were responsible for 47% of strokes

fossa neuroimaging (A.B., S.Y.) and 2 otoneurologists (D.N.-T., (table 1).

J.C.K.). We show selected images representative of each anatomical

region involved. We compared the rate of false-negative MRIs with

DISCUSSION Small strokes causing AVS were found

the rate of false-negative bedside testing, and compared these same

tests with results in those with larger strokes presenting AVS. We throughout the brainstem, although disproportionately

report similar measures for those with isolated AVS. We used Fisher in the lateral medulla and affecting the inferior cerebel-

exact test to compare proportions across groups and the lar peduncle; isolated cerebellar lesions were uncommon

170 Neurology 83 July 8, 2014

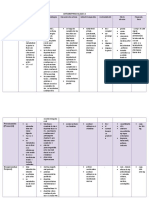

Table 1 Clinicoradiographic case descriptions, listed from caudal to rostral, based on anatomical lesion location

HINTS

Age, Direction-changing 1st

Patient y Sex Cranial/tract signs HIT horizontal nystagmus Skew MRI Location (vestibular structure) Etiologya

1 61 F Decreased pin R face, L 2 2 1 Normal R intermediolateral medulla (ICP) Lacunar

body

2 85 M None 2 No nystagmus 1 Stroke R intermediolateral medulla (ICP) Lacunar

3 67 M None 2 2 2 Normal L intermediolateral medulla (ICP) Lacunar

4 41 M None (evolved later) 2 1 1 Normal R intermediolateral medulla (ICP) VA dissection

5 75 M R face numbness 2 No nystagmus 1 Stroke L posterolateral medulla (ICP) VA occlusion

6 51 F Dysphagia 2 2 2 Stroke R posterolateral medulla (ICP) VA occlusion

7 83 M None 2 No nystagmus 2 Normal R posterolateral medulla (ICP) Atrial fibrillation

8 61 F None 2 No nystagmus 2 Stroke L posterolateral medulla (ICP, MVN) Lacunar

9 71 M Upbeat nystagmus 2 NA (vertical) 2 Normal R intermedio-/posterolateral medulla (ICP, MVN) VA occlusion

10 64 M None 2 2 1 Normal L pontomedullary, lateral periventricular (ICP) Lacunar

11 80 M Ocular tilt reaction 1 1 1 Normal R pontomedullary, medial periventricular (MVN) VA dissection

12 58 F L facial palsy; L hearing 1 2 2 Stroke L lateral pons (root entry zone 8th nerve Lacunar

loss complex)

13 62 M Upbeat nystagmus 2 NA (vertical) 1 Normal L periventricular (ICP) Lacunar

14 50 F Torsional/downbeat 2 NA (vertical) 2 Stroke R periventricular (nodulus) Bilateral VA

nystagmus occlusion

15 70 M Ocular tilt reaction 2 No nystagmus 1 Stroke R midbrain tegmentum (possibly INC or nearby Lacunar

connections)

Abbreviations: HINTS 5 head impulse, nystagmus, test-of-skew; HIT 5 head impulse test; ICP 5 inferior cerebellar peduncle; INC 5 interstitial nucleus of

Cajal; MVN 5 medial vestibular nucleus; NA 5 not applicable; VA 5 vertebral artery.

Symbols: 1 5 present/abnormal; 2 5 absent/normal.

a

Etiologies were assigned based on clinicoradiographic criteria after a thorough, standardized stroke workup test battery. None had pathologic

confirmation.

in our series. Approximately three-fourths of patients The one patient in this series missed by HINTS would

had an isolated AVS presentation, and clinical have been captured by the recently described HINTS

examination was far superior at detecting central plus approach that identifies hearing loss as a sign of

lesions than early MRI neuroimaging. Approximately anterior inferior cerebellar artery infarction in patients

half were due to nonlacunar mechanisms, including 6 with AVS.9 In the hands of subspecialists, HINTS

cases of vertebral artery dissection or occlusion. These plus has an estimated sensitivity of 99% and speci-

results add to the growing body of knowledge about ficity of 97% for identifying central causes of AVS,

isolated vestibular presentations of stroke and have whether isolated or not.9 Similar results, however,

important implications for clinical practice. can probably be achieved by general neurologists after

Historically, isolated vertigo was not considered a modest amounts of training.15

stroke symptom,11 and, by design, this clinical presenta- Relying on immediate MRI to exclude patients

tion has been systematically excluded from most formal with stroke AVS is probably not sufficient. In our

stroke studies.12,13 Recent research, however, makes clear clinical practice, we do not accept a negative MRI

that isolated vertigo, whether transient13 or persistent,1,2,8 ,72 hours after symptom onset as definitive if ocu-

is a common presentation of posterior circulation TIA lomotor signs suggest otherwise, and routinely repeat

and stroke. In fact, when cerebrovascular patients present imaging in such patients. To reduce the need for

vestibular symptoms, they are isolated much more often duplicative MRIs, it may sometimes be appropriate

than nonisolated at initial presentation,1,13 and isolated to wait until 48 to 72 hours after symptom onset

vertigo or dizziness is the most common initial manifes- before obtaining the first MRI (e.g., if the stroke etio-

tation of vertebrobasilar ischemia.13 logy is known and the patient is clinically stable).

While isolated transient vertigo still presents sub- Optimal, evidence-based neuroimaging protocols in

stantial diagnostic challenges, ample evidence now in- AVS await further study, although we recently pro-

dicates that bedside oculomotor examinations reliably posed one possible strategy (figure e-1).9

distinguish central from peripheral causes in those with The prognosis and impact of early treatment for

persistent, continuous symptoms (i.e., AVS).1,2,8,9,14 these specific patients remain largely unknown, but

Neurology 83 July 8, 2014 171

Figure 1 Montage of causal lesions in 9 of 15 patients with small strokes causing acute vestibular syndrome

Montage of causal lesions in 9 of 15 patients with small strokes causing acute vestibular syndrome (axial MRI/diffusion-

weighted imaging through the brainstem, arranged from caudal to rostral). Only selected images representative of each ana-

tomical region involved are shown.

accurate diagnosis of these patients would seem quite it is our clinical practice that isolated AVS patients

important. The odds of stroke recurrence or death is with suspicious HINTS findings or new hearing loss

greater with nonlacunar than lacunar mechanisms.16 be treated with the same urgency as other nondis-

Vertebrobasilar occlusions or dissections are found in abling strokes (e.g., admission and stroke risk factor

more than half of patients with AVS,1 and were seen workup). Accurately diagnosing these strokes by bed-

in 40% of the present series of small infarctions. Dis- side HINTS could potentially save lives and decrease

section is more frequent in young adults relative to disability through prompt intervention. At the very

unselected stroke populations,17 and youth is a risk least, early detection could lead to the study of new

factor for missed stroke.18 Misdiagnosed posterior cir- posterior circulation stroke therapies that might be

culation stroke patients appear to fare worse than applied to this understudied group of posterior fossa

those diagnosed and treated promptly.2 Dissections infarctions.

are often not suspected and may be difficult to detect, Limitations include a small sample size, imperfect

but the clinical outcomes of missed vertebral artery case capture (some small strokes may have been

dissection in young patients can be disastrous.19 Opti- missed even by second MRI or in isolated AVS pa-

mal treatment for vertebrobasilar stenosis and dissec- tients diagnosed as peripheral by clinical follow-up

tion remains controversial, and clinical trials are rather than repeat imaging), and unknown conse-

ongoing to determine whether early thrombolysis in quences of misdiagnosis (since we report only those

those with nondisabling posterior circulation strokes correctly identified). If small strokes were misclassi-

is beneficial. Absent clinical trials evidence, however, fied as peripheral (i.e., not included here), results

Table 2 Neuroimaging and oculomotor assessment in small vs large strokes presenting AVS

Small strokes (10 mm), Large strokes (>10 mm),

% (n of 15) % (n of 90) p Value

a

False-negative initial MRI 53.3 (8) 7.8 (7) ,0.001

False-negative HINTS examination 6.7 (1) 3.3 (3) 0.46

9

False-negative HINTS plus hearing examination 0 (0) 1.1 (1) 1

Abbreviations: AVS 5 acute vestibular syndrome; HINTS 5 head impulse, nystagmus, test of skew.

a

All strokes were confirmed by MRI/diffusion-weighted imaging neuroimaging. For false-negative initial MRIs, confirmatory

scans were obtained several days after the initial false-negative scan.

172 Neurology 83 July 8, 2014

could have overstated HINTS sensitivity; however, A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular

MRI sensitivity would then also be overstated, so it syndrome. CMAJ 2011;183:E571E592.

3. Saber Tehrani AS, Coughlan D, Hsieh YH, et al. Rising

is not plausible that this limitation could have abol-

annual costs of dizziness presentations to US emergency

ished the large sensitivity advantage of HINTS over departments. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:689696.

MRI. Some anatomical loci known to cause AVS 4. Kim AS, Sidney S, Klingman JG, Johnston SC. Practice

were not included here (e.g., no cases with hemi- variation in neuroimaging to evaluate dizziness in the ED.

spheric insular cortex7 lesions or dorsolateral pontine Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:665672.

tegmental lesions with associated masseter paresis20). 5. Kerber KA, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Smith MA,

Morgenstern LB. Stroke among patients with dizziness,

Theoretically, our results might not generalize to

vertigo, and imbalance in the emergency department:

strokes occurring in these other sites.

a population-based study. Stroke 2006;37:24842487.

Small strokes involving vestibular projections 6. Kim HJ, Lee SH, Park JH, Choi JY, Kim JS. Isolated

within the brainstem or cerebellum can produce vestibular nuclear infarction: report of two cases and

AVS. These patients most often have lateral medullary review of the literature. J Neurol 2014;261:121129.

infarctions lacking classic signs. The HINTS plus 7. Kim HA, Lee H. Recent advances in central acute vestibular

battery of oculomotor tests identifies these patients syndrome of a vascular cause. J Neurol Sci 2012;321:1722.

8. Newman-Toker DE, Kattah JC, Alvernia JE, Wang DZ.

with greater accuracy than early MRI-DWI, which is

Normal head impulse test differentiates acute cerebellar strokes

falsely negative in more than half. We found nonlacu- from vestibular neuritis. Neurology 2008;70:23782385.

nar mechanisms in approximately half of our patients, 9. Newman-Toker D, Kerber K, Hsieh Y, et al. HINTS

suggesting greater risk than might otherwise be outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous

assumed for patients with such small infarctions. vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:986996.

Future studies should seek to determine whether early 10. Herve D, Mangin JF, Molko N, Bousser MG, Chabriat H.

Shape and volume of lacunar infarcts: a 3D MRI study in

diagnosis in these patients improves clinical outcomes.

cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical in-

farcts and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke 2005;36:23842388.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

11. Fisher CM. Vertigo in cerebrovascular disease. Arch

Ali S. Saber Tehrani: drafted the manuscript, reviewed and critically edi-

ted the manuscript, and approved the final version. Jorge C. Kattah: as-

Otolaryngol 1967;85:529534.

sisted in data collection, reviewed and critically edited the manuscript, 12. A classification and outline of cerebrovascular diseases: II.

and approved the final version. Georgios Mantokoudis: reviewed and crit- Stroke 1975;6:564616.

ically edited the manuscript, and approved the final version. John H. Pula 13. Paul NL, Simoni M, Rothwell PM. Transient isolated

and Deepak Nair: assisted in data collection, reviewed and critically edi- brainstem symptoms preceding posterior circulation stroke:

ted the manuscript, and approved the final version. Ari Blitz and Sarah a population-based study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:6571.

Ying: assisted in data coding, reviewed and critically edited the manu- 14. Huh YE, Koo JW, Lee H, Kim JS. Head-shaking aids in

script, and approved the final version. Daniel F. Hanley and David S. the diagnosis of acute audiovestibular loss due to anterior

Zee: assisted in study design/conception, reviewed and critically edited

inferior cerebellar artery infarction. Audiol Neurootol

the manuscript, and approved the final version. David E. Newman-

2013;18:114124.

Toker: designed the study and analytic plan, reviewed and critically edi-

ted the manuscript, and approved the final version.

15. Chen L, Lee W, Chambers BR, Dewey HM. Diagnostic

accuracy of acute vestibular syndrome at the bedside in a

stroke unit. J Neurol 2011;258:855861.

STUDY FUNDING

16. Jackson C, Sudlow C. Comparing risks of death and recur-

No targeted funding reported.

rent vascular events between lacunar and non-lacunar

infarction. Brain 2005;128:25072517.

DISCLOSURE 17. Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, et al. Clinical

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: a

Neurology.org for full disclosures. systematic review. Neurologist 2012;18:245254.

18. Newman-Toker DE, Moy E, Valente E, Coffey R,

Received December 11, 2013. Accepted in final form March 26, 2014. Hines A. Missed diagnosis of stroke in the emergency

department: a cross-sectional analysis of a large population-

REFERENCES based sample. Diagnosis 2014. Available at: http://www.

1. Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman- degruyter.com/view/j/dx.2014.1.issue-2/dx-2013-0038/dx-

Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestib- 2013-0038.xml. Accessed May 23, 2014.

ular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination 19. Savitz SI, Caplan LR, Edlow JA. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of

more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. cerebellar infarction. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:6368.

Stroke 2009;40:35043510. 20. Hopf HC. Vertigo and masseter paresis: a new local brain-

2. Tarnutzer AA, Berkowitz AL, Robinson KA, Hsieh YH, stem syndrome probably of vascular origin. J Neurol 1987;

Newman-Toker DE. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? 235:4245.

Neurology 83 July 8, 2014 173

Você também pode gostar

- Vestibular Neuritis Affects Both Superior and Inferior Vestibular NervesDocumento10 páginasVestibular Neuritis Affects Both Superior and Inferior Vestibular NervesSabina BădilăAinda não há avaliações

- Algoritmo en UrgenciasDocumento9 páginasAlgoritmo en UrgenciasJulioAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Continuous VertigoDocumento6 páginasAcute Continuous VertigorobertoAinda não há avaliações

- Mayoclinproc 85-5-004Documento6 páginasMayoclinproc 85-5-004Alain SánchezAinda não há avaliações

- 5 THDocumento17 páginas5 THMohamed MohammedAinda não há avaliações

- 2017 - Morris Et Al-AnnotatedDocumento7 páginas2017 - Morris Et Al-AnnotatedCemal GürselAinda não há avaliações

- In-Hospital Stroke Recurrence and Stroke After Transient Ischemic AttackDocumento15 páginasIn-Hospital Stroke Recurrence and Stroke After Transient Ischemic AttackferrevAinda não há avaliações

- Parinaud Syndrome: Any Clinicoradiological Correlation?: L. Pollak - T. Zehavi-Dorin - A. Eyal - R. Milo - R. Huna-BaronDocumento6 páginasParinaud Syndrome: Any Clinicoradiological Correlation?: L. Pollak - T. Zehavi-Dorin - A. Eyal - R. Milo - R. Huna-BaronJessica HerreraAinda não há avaliações

- Use of HINTS in The Acute Vestibular Syndrome. An Overview: Jorge C KattahDocumento7 páginasUse of HINTS in The Acute Vestibular Syndrome. An Overview: Jorge C KattahboriuiAinda não há avaliações

- Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging of Retinal Hemorrhages in Abusive Head TraumaDocumento7 páginasSusceptibility-Weighted Imaging of Retinal Hemorrhages in Abusive Head TraumaHercya IsabelAinda não há avaliações

- Acute DizzinessDocumento14 páginasAcute DizzinesstsyrahmaniAinda não há avaliações

- Portable, Bedside, Low-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging For Evaluation of Intracerebral HemorrhageDocumento11 páginasPortable, Bedside, Low-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging For Evaluation of Intracerebral HemorrhageRenan de LimaAinda não há avaliações

- Noc110069 346 351Documento6 páginasNoc110069 346 351Carlos AlvaradoAinda não há avaliações

- Initial Evaluation VertigoDocumento8 páginasInitial Evaluation VertigoTanri Hadinata WiranegaraAinda não há avaliações

- Jamaneurology Topcuoglu 2017 Oi 170047Documento8 páginasJamaneurology Topcuoglu 2017 Oi 170047LadycherryAinda não há avaliações

- AEDR 2015 v3.2 Prehospital EMS For Seizure Patients 22 27Documento6 páginasAEDR 2015 v3.2 Prehospital EMS For Seizure Patients 22 27Chetan DhobleAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Relevance of Acute Cerebral Microinfarcts in Vascular Cognitive ImpairmentDocumento10 páginasClinical Relevance of Acute Cerebral Microinfarcts in Vascular Cognitive Impairmentzefri suhendarAinda não há avaliações

- Kamiya Matsuoka2017Documento5 páginasKamiya Matsuoka2017Jasper CubiasAinda não há avaliações

- Ferro 2008Documento8 páginasFerro 2008Carlos RiquelmeAinda não há avaliações

- NEURCLINPRACT2021070298Documento7 páginasNEURCLINPRACT2021070298Marysol UlloaAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Features of Intracranial Vestibular SchwannomasDocumento6 páginasClinical Features of Intracranial Vestibular SchwannomasIndra PrimaAinda não há avaliações

- Nejme 2400102Documento3 páginasNejme 2400102linjingwang912Ainda não há avaliações

- Seizure After StrokeDocumento6 páginasSeizure After StrokenellieauthorAinda não há avaliações

- Hongliang Mao Short and Long Term Response of VagusDocumento16 páginasHongliang Mao Short and Long Term Response of VagusArbey Aponte PuertoAinda não há avaliações

- Xia 2014Documento5 páginasXia 2014Akmal Niam FirdausiAinda não há avaliações

- Necessity of EEG and CT Scan For Accurate Diagnosis of Idiopathic (Partial / Generalised) Seizures in ChildrenDocumento4 páginasNecessity of EEG and CT Scan For Accurate Diagnosis of Idiopathic (Partial / Generalised) Seizures in ChildrenInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- The Spectrum of Vestibular MigraineDocumento14 páginasThe Spectrum of Vestibular MigraineRudolfGerAinda não há avaliações

- Acute and Episodic Vestibular Syndromes Caused by Ischemic Stroke: Predilection Sites and Risk FactorsDocumento12 páginasAcute and Episodic Vestibular Syndromes Caused by Ischemic Stroke: Predilection Sites and Risk FactorsKarl Martin PinedaAinda não há avaliações

- Dropped Shoulder Syndrome: A Cause of Lower Cervical RadiculopathyDocumento5 páginasDropped Shoulder Syndrome: A Cause of Lower Cervical RadiculopathyMudassar SattarAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal r5Documento8 páginasJurnal r5Rezkina Azizah PutriAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation Other Than Major Rupture - GreenbergDocumento13 páginasPresentation Other Than Major Rupture - GreenbergAlexandra CAinda não há avaliações

- Hipertensão IntracranianaDocumento6 páginasHipertensão IntracranianaFelipe Stoquetti de AbreuAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Neurology and NeurosurgeryDocumento6 páginasClinical Neurology and NeurosurgeryNurul Azmi Rosmala PutriAinda não há avaliações

- Neuroasia 2021 261 035Documento5 páginasNeuroasia 2021 261 035raj.insigneAinda não há avaliações

- Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: Aditya Iyer, MD, MS, Tej D. Azad, Ba, and Suzanne Tharin, MD, PHDDocumento7 páginasCervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: Aditya Iyer, MD, MS, Tej D. Azad, Ba, and Suzanne Tharin, MD, PHDMây Trên TrờiAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Stroke-2006-Singer-2726-32Documento8 páginas3 Stroke-2006-Singer-2726-32lady1605Ainda não há avaliações

- Ultrasound in Emergency Medicine: Use of Ocular Ultrasound For The Evaluation of Retinal DetachmentDocumento5 páginasUltrasound in Emergency Medicine: Use of Ocular Ultrasound For The Evaluation of Retinal DetachmentZarella Ramírez BorreroAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S0006497119716358 MainDocumento3 páginas1 s2.0 S0006497119716358 MainHijaz HijaAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Outcomes of Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy Evaluated With Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance ImagingDocumento6 páginasClinical Outcomes of Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy Evaluated With Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance ImagingDrsandy SandyAinda não há avaliações

- HSA Controversias 2016Documento9 páginasHSA Controversias 2016Ellys Macías PeraltaAinda não há avaliações

- Facial UltrassomDocumento7 páginasFacial UltrassomcarlosAinda não há avaliações

- Seizure: Nick Kane, Lesley Grocott, Ros Kandler, Sarah Lawrence, Catherine PangDocumento6 páginasSeizure: Nick Kane, Lesley Grocott, Ros Kandler, Sarah Lawrence, Catherine PangRenard ChristianAinda não há avaliações

- InvestigationsDocumento28 páginasInvestigationsAndrei BulgariuAinda não há avaliações

- Jama 268 6 030Documento6 páginasJama 268 6 030Thiago Scharth MontenegroAinda não há avaliações

- Clinics 5Documento19 páginasClinics 5Renju KuriakoseAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of First Seizure and Newly Diagnosed.4Documento31 páginasEvaluation of First Seizure and Newly Diagnosed.4veerraju tvAinda não há avaliações

- Malak 2021Documento19 páginasMalak 2021Firmansyah FirmansyahAinda não há avaliações

- Infarcts in MigraineDocumento10 páginasInfarcts in MigraineAbdul AzeezAinda não há avaliações

- Art 3Documento11 páginasArt 3Daniel TorresAinda não há avaliações

- Superiority of Continuous Over Intermittent Intraoperative Nerve Monitoring in Preventing Vocal Cord PalsyDocumento9 páginasSuperiority of Continuous Over Intermittent Intraoperative Nerve Monitoring in Preventing Vocal Cord PalsyazharbattooAinda não há avaliações

- Approach To HeadacheDocumento61 páginasApproach To Headachesabahat.husainAinda não há avaliações

- Vidence Ased IagnosticsDocumento41 páginasVidence Ased IagnosticsAnisa ArmadaniAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal 2Documento11 páginasJurnal 2ararapiaAinda não há avaliações

- Accuracy of Imaging Technologies in The DiagnosisDocumento7 páginasAccuracy of Imaging Technologies in The DiagnosisAGGREY DUDUAinda não há avaliações

- Burden of Dizziness and Vertigo in The CommunityDocumento8 páginasBurden of Dizziness and Vertigo in The CommunityEcaterina ChiriacAinda não há avaliações

- Z Score SISCOMDocumento9 páginasZ Score SISCOMAiswarya HariAinda não há avaliações

- ARUBA Medical Management For NeurologyDocumento8 páginasARUBA Medical Management For NeurologyFajar Rudy QimindraAinda não há avaliações

- Lee 2007Documento6 páginasLee 2007mmartinezs2507Ainda não há avaliações

- Postpartum Endometritis: - Infection of The Decidua (Ie, - Endomyometritis - ParametritisDocumento18 páginasPostpartum Endometritis: - Infection of The Decidua (Ie, - Endomyometritis - ParametritisDeTe Gun Rap'er ConkK'exsAinda não há avaliações

- Self Management Program Participation by Older Adults With DiabetesDocumento13 páginasSelf Management Program Participation by Older Adults With DiabetesDeTe Gun Rap'er ConkK'exsAinda não há avaliações

- Community Empowerment For Primary Prevention of Type 2 DiabetesDocumento25 páginasCommunity Empowerment For Primary Prevention of Type 2 DiabetesDeTe Gun Rap'er ConkK'exsAinda não há avaliações

- Small Stroke Causing Severe VertigoDocumento5 páginasSmall Stroke Causing Severe VertigoDeTe Gun Rap'er ConkK'exsAinda não há avaliações

- Trombosis ArteriDocumento4 páginasTrombosis ArteriDeTe Gun Rap'er ConkK'exsAinda não há avaliações

- VarisesDocumento7 páginasVarisesDeTe Gun Rap'er ConkK'exsAinda não há avaliações

- Pituitary AdenomasDocumento48 páginasPituitary AdenomasRegina Lestari0% (1)

- Pediatric LeukemiasDocumento42 páginasPediatric LeukemiasslyfoxkittyAinda não há avaliações

- 8 - Sullivan - Interpersonal TheoryDocumento4 páginas8 - Sullivan - Interpersonal TheorystephanieAinda não há avaliações

- Painkiller: Seeking Marijuana Addiction Treatment: The Signs of An AddictDocumento6 páginasPainkiller: Seeking Marijuana Addiction Treatment: The Signs of An AddictMihaelaSiVictoriaAinda não há avaliações

- Psicoterapia Interpersonal en El Tratamiento de La Depresión MayorDocumento11 páginasPsicoterapia Interpersonal en El Tratamiento de La Depresión MayorAndrea MiñoAinda não há avaliações

- Cardiac Catheterization and MonitoringDocumento40 páginasCardiac Catheterization and MonitoringMarissa Asim100% (1)

- SDJ 2020-06 Research-2Documento9 páginasSDJ 2020-06 Research-2Yeraldin EspañaAinda não há avaliações

- Autologous Rib Microtia Construction: Nagata TechniqueDocumento15 páginasAutologous Rib Microtia Construction: Nagata Techniqueandi ilmansyahAinda não há avaliações

- Situation 2Documento8 páginasSituation 2Rodessa Mandac TarolAinda não há avaliações

- Classical and Modern Theories of AcupunctureDocumento11 páginasClassical and Modern Theories of AcupunctureAbhishek Dubey100% (1)

- Nikolas Rose - Disorders Witouht BordersDocumento21 páginasNikolas Rose - Disorders Witouht BordersPelículasVeladasAinda não há avaliações

- BET Newsletter May2010 PDFDocumento5 páginasBET Newsletter May2010 PDFSatish BholeAinda não há avaliações

- Stable Bleaching PowderDocumento1 páginaStable Bleaching PowderAbhishek SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Xeo TreatmentsDocumento13 páginasXeo TreatmentsSimone WallisAinda não há avaliações

- Respiratory Physiology: Control of The Upper Airway: Richard L. Horner University of TorontoDocumento8 páginasRespiratory Physiology: Control of The Upper Airway: Richard L. Horner University of TorontoDopamina PsicoactivaAinda não há avaliações

- ASCCP Management Guidelines - August 2014 PDFDocumento24 páginasASCCP Management Guidelines - August 2014 PDFAnita BlazevskaAinda não há avaliações

- The Effectiveness of Treatment For Adult Sexual OffendersDocumento6 páginasThe Effectiveness of Treatment For Adult Sexual OffendersStephen LoiaconiAinda não há avaliações

- NRSG - Documentation and Quality Management in IvtDocumento12 páginasNRSG - Documentation and Quality Management in IvtRamon Carlo AlmiranezAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture - 1 Components of Sewage Collection SystemDocumento19 páginasLecture - 1 Components of Sewage Collection SystemDanial Abid100% (1)

- Cause and Effect EssayDocumento6 páginasCause and Effect Essaywanderland90Ainda não há avaliações

- Myocardial InfarctionDocumento2 páginasMyocardial InfarctionnkosisiphileAinda não há avaliações

- CystoceleDocumento7 páginasCystocelesandeepv08Ainda não há avaliações

- Herniated Nucleus Pulposus (HNP)Documento21 páginasHerniated Nucleus Pulposus (HNP)Kaye100% (1)

- Typhon Cases 2Documento7 páginasTyphon Cases 2api-483865455Ainda não há avaliações

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocumento14 páginasNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentMohamed RashadAinda não há avaliações

- Post-Partum HemorrhageDocumento15 páginasPost-Partum Hemorrhageapi-257029163Ainda não há avaliações

- Motor Control TheoriesDocumento19 páginasMotor Control Theoriessridhar_physio50% (2)

- Antiaritmice Clasa I A MedicamentDocumento3 páginasAntiaritmice Clasa I A MedicamentAndreea ElenaAinda não há avaliações

- AHA ACLS Megacode ScenariosDocumento6 páginasAHA ACLS Megacode ScenariosVitor Hugo G Correia86% (7)

- SchezophreniaDocumento22 páginasSchezophreniaxion_mew2Ainda não há avaliações