Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

ALTFELD - The Decision To Ally. A Theory and Test

Enviado por

dragan_andrei_1Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

ALTFELD - The Decision To Ally. A Theory and Test

Enviado por

dragan_andrei_1Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

University of Utah

Western Political Science Association

The Decision to Ally: A Theory and Test

Author(s): Michael F. Altfeld

Reviewed work(s):

Source: The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Dec., 1984), pp. 523-544

Published by: University of Utah on behalf of the Western Political Science Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/448471 .

Accessed: 19/12/2012 10:59

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Utah and Western Political Science Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to The Western Political Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE DECISION TO ALLY: A THEORY AND TEST

MICHAEL F. ALTFELD

MichiganStateUniversity

A GREAT dealofworkininternational relationshasbeendevotedto

thestudyof alliance formation.Mostof theearlyworkin thisarea

centered on theorizingor speculatingabout the formationof

particularalliances (Liska 1968; Russett1968; Rosen 1970). More recent

work,spurredbythediffusionof time-seriesanalysisintopoliticalscience

as well as the availabilityof data, has focused on alliance as a systemic

phenomenon(McGowan and Rood 1975; Job 1976; Siversonand Duncan

1976). Unfortunately,neitherof these approaches has been able to pro-

vide us witha theoryof alliance formation.

This stateof affairswould notbe so bad ifalliances were unimportant.

Yet, at least two studies have demonstratedthat alliances are of great

importanceforthe initiationand spread of internationalconflict(Altfeld

and Bueno de Mesquita 1979; Bueno de Mesquita 1981).

In this paper I will employ some notions of micro-economicsfirst

introducedbyBruce Berkowitz(1983) to the studyof alliance cohesion in

order to develop a simple theoryof the process by which national gov-

ernmentschoose to formmilitaryalliances. I will then proceed to testa

necessarybut notsufficient conditionforalliance formationderivedfrom

the theoryon the set of major power alliances in the 19th century.

THE THEORY

I. Major TheoreticalAssumptions

Four major assumptionslie at the heart of thiswork. First,I assume

that the decision-makerswho make up each nation's governmentare

rationalin the sense thattheyare expected utilitymaximizers.Second, I

assume that,eitherbecause there is a dictatorin foreignpolicy matters

(Bueno de Mesquita 1981) or because the preferencesof the decision-

makersobey value restriction(Sen 1970; Allisonand Halperin 1972), the

preferencesof each set of decision-makersmakingup a governmentare

collectivelytransitive.Third, I assume thatno possiblealliance partneris,

a priori,irrelevantto any government.That is, the decision not to allyis

made in exactlythe same way as the decision to ally,by calculatingcosts

and benefits.Finally,I assume that the decision-makerswho make up

governments,when theymake such decisionsas joining or initiatingwars

or formingalliances, do so according to a simple Cournot type rule

(Fellner 1949). That is, when theyare faced witha choice, theyassume

NOTE: I would like to thank Mr. ChristopherBrown and Ms. Harriet Dhanak of the MSU

PolitimetricsLaboratory,withoutwhose help I would never have been able to testthe

theorypresentedin thispaper. I would also liketo thankJohnAldrich,Bruce Bu1 noode

Mesquita, Gary Miller and Jim Morrow for theirmany helpful comments.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

524 PoliticalQuarterly

Western

thateverythingwill be the same aftertheirchoice as it was before their

choice except for theirchoice.1

II. Arguments oftheGovernment's UtilityFunction2

I assumed above that the set of decision-makerswho make up each

governmenthave collectivelytransitivepreferences.The resultof thisis

thatI can establishat leastan ordinal utilityfunctionforeach government

as a whole. Call thisfunctionU = U(X .. ,X) where X . . X may be

variousentitiesincludinggoods, services,voters,payrolls,patronage,etc.

For the purposes of thispaper I willassume thateach government'sutility

functionis definedover threecommodities:nationalsecurity(S), civilian

wealth(W), and freedomof action or "autonomy"(A), so thatU = U (S,

W, A). I will treatthese entitiesas being essentiallytheoreticalin nature

and willtherefore,forthe timebeing,leave themundefinedexcept to say

thatI assume thatwealth,securityand autonomyare differentgoods in

the sense thatone does not, for example, take one's amount of security

and/orautonomyintoaccount when computingone's wealth,thatwealth

is related to the totalamount of governmentalresources devoted to the

civilianeconomyand thatautonomyis related to the government'scapa-

cityto adopt whateverpositionsit wishesto withregard to international

issues salient to it and to change those positionsat will.3

Given that U = U (S, W, A), aU/dS is called the marginal utilityof

securityand representsthe change in U for a small change in security

holding wealth and autonomy constant. Further,aU/aW is called the

marginal utilityof wealth and representsthe change in U for a small

change in wealthholdingsecurityand autonomyconstant.Finally,aU/aA

is called the marginalutilityof autonomyand representsthe change in U

for a small change in autonomy holding securityand wealth constant.

Further,I assume that aU/aS, aU/RW,and aU/aA are always positive.

III. The NatureofSecurity

and itsRelationship and Wealth

toAutonomy

So far in the analysisI have treatedsecurityas a standard economic

good. This is not quite correct,however. The reason for this is that

securityis notpurchased bythegovernmentbut ratherproduced byitout

of inputs. The governmentis thus both the producer and consumer of

security.4

'This assumptionmay not sit well withsome, especiallythose who prefera more dynamic,

game theoreticapproach to alliance formation.The assumptionof simpleCournot type

rationalityhas, however, proven quite powerful in other contexts (see, especially,

McGuire 1974, 1982) and seems quite appropriate as a firstcut.

2The analysis in this section and sections III, IV and V is adapted in large part from

Henderson and Quandt (1980).

3Thus, by"domesticwealth"I mean all moniesspentbythegovernmentwhichare notspent

on procurementof armaments.Further,although at least one study(Hollenhorstand

Ault 1971) has shown that defense spending may have positiveimpacts on the non-

defense economy I will,for analyticalpurposes, ignore these effects.

4For a detailed analysisof such situationssee Becker (1971: chs. 10 and 10*).

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 525

Securityis, of course, the resultof manydifferent"factorsof produc-

tion" such as industrialcapacity,natural resourcesand a skilledpopula-

tion,whichare largelyunmanipulablebythegovernmentat leastover the

shortrun. I thereforeassume thatgovernmentstake as "given"whatever

securityis provided by such non-manipulablefactorsand then,if neces-

sary,produce additional securityfromfactorswhich are manipulable.5

I assume thatthereare two such manipulables foreach government;

procurementof armaments,designated R, and militaryalliances, desig-

nated L. (The assumptionthatincreasedsecurityis theexclusiveor at least

primarybenefitof alliances maybe found in much theorizingin interna-

tionalrelations.Examples would include Morgenthau 1973; Liska 1968;

Claude 1962.) I can thus establisha productionfunctionfor securityin

addition to that given by non-manipulable factors.Call this function

S = S(R,L)." Then aS/aR is the marginal product of armaments and

representsthe change in securityfora smallchange in armamentshold-

ing alliances constant.Further,dS/IL is the marginalproductof alliances

and represents the change in securityfor a small change in alliance

support holding armamentsconstant.I willassume that aS/aR is always

positive.That is, securitycan always be increased by increasing arma-

ments (holding other nations' armamentslevels constant)although the

rate of this increase may decline as higher levels of armaments are

reached (thatis, a2 S/aR2maybe negativeover some range of values of R.)

This is not the case, however, for alliances. While it is true that some

alliances can increasea nation'ssecurity,itis also true thatsome alliances

willadd nothingat all to a nation'ssecurityor even reduce itssecurityby

placingitin a morevulnerablepositionthanitwas in beforeitchose tojoin

the alliance. Thus, aS/dL will be positivefor some alliances but zero or

even negative for others.

Having previouslydefined the marginalproductsof armamentsand

alliance support,I can now definethe "rate of technicalsubstitution"or

RTS. The ratio

aS/aR

aS/aL

is called theRTS ofalliancesforarmamentsand givestherateat whichthe

governmentwould be willingto substitutealliances for armamentsper

unit of alliance in order to maintaina given level of security.

"Theoretically,thisrequires thatU be a separablefunctionof S, W and A. If thisis the case,

then I am merelymovingthe base-pointfromwhichutilityis calculated to the rightby

takingas "given" the security/utilityproduced by non-manipulables.

"An alternativeassumptionwhichmightbe made here is thatalliances and armamentsare

notsubstitutesbutcomplements.Murdoch and Sandler (1982), forexample, argue that

two of the goods produced by NATO (nuclear and conventionalforces)are comple-

ments. For an alliance itselfto be a complement to militaryexpenditures,however,

would seem to require a case in whicha powerfulnationmakes an alliance witha weak

but strategicallylocated small nation. Thus, in order to take advantage of its new

alliance,the large nationwould have to spend more on itsmilitary.For thelarge nation,

then,the alliance would be a complement.For the small nation,however,it would be a

substitute.Since, in thispaper, I focus only on alliancesamongmajor powers,it would

seem unlikelythatthe case of an alliance as a complementarygood would arise.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

526 Western

PoliticalQuarterly

Conversely,

aS/aL

aS/aR

is the RTS of armamentsfor alliances and gives the rate at which the

governmentwould be willingto substitutearmamentsfor alliances per

unit of armaments.

IV. The Problemof Tradeoffs

In deciding on the specificmix of armamentsand alliances whichwill

be used to produce its desired level of security,each governmentmust

take into account the "price" of each factor of production. As James

Buchanan (1969: 42-43) has pointed out, "Cost is that which the

decision-takersacrificesor gives up when he makes a choice." Thus, the

"price" of each factorreallyoccurs in termsof somethingelse whichthe

governmentcannotconsume because ithas decided to produce increased

security.In particular,assuming finiteresources at any given time,any

marginalpurchase of armamentsmustreduce the totalresourcesavaila-

ble to the civilian economy thus reducing domestic wealth as I have

definedit.Thus, ceterusparibus,the"cost"of increasingsecuritythrough

arms purchases is computed in termsof lost wealth(a similartradeoffis

postulated by McGuire 1965: ch. 3.

While the price of armaments seems fairlyclear, the price of an

alliance is somewhat less straightforwardto assess. Some alliances, of

course (e.g., NATO), involvea considerableexpenditureof resourcesby

all parties on militarycommissions,joint planning,etc. Many alliances,

however, perhaps most, do not. What all alliances have in common,

though,is a promise by each side to take specificactions in the event of

specificcontingencies.Such promisesare usuallyconsidered to be legally

bindingand have, in the past, usually been kept. Altfeldand Bueno de

Mesquita (1979), forexample, findthatnationshavingdefense pactswith

other nations almost invariablycome to the aid of their partnerswhen

thosepartnersare attacked.Thus, alliancescan be seen as deprivingeach

partyof some of its freedomof action. In addition, alliances tend to tie

nationsmore broadlyto each others'positionson relevantissues so thatit

becomes difficult foreitherpartyto adopt policystandstoo different from

thoseof itsally (some examples of those who have adopted thisor similar

assumptionsinclude Organski 1968; Singer and Small 1968; Berkowitz

1983; Bueno de Mesquita 1975, 1981; Altfeldand Bueno de Mesquita

1979). I assume, then, that the cost of an alliance to a governmentis

computed in termsof the autonomywhichmustbe given up in order to

form the alliance. Furthermore,I will assume that some autonomy is

alwayslost in forminga new alliance and thatsome wealthis alwayslost

when armamentsare increased.

Given thatthe costsof armamentsreallytake place in termsof wealth

and autonomyrespectively,I can establishtwofunctions,W = Gi(R) and

A = G2(L), whichrelatewealthto armamentsand autonomyto alliances.

Further,I assume thatthe derivativesof Gi and G2 are alwaysnegativeso

that the amount of civilian wealth available declines as the amount of

armamentsproduced increases,whiletheamountof autonomywhichthe

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 527

governmentpossesses on internationalissues declines as the amount of

alliance support which it possesses increases.

V. Governmental Equilibriumand ConditionsfortheFormation and Dissolution

ofAlliances

Given the above discussionI can now postulatethe conditionsunder

which the governmentwill be in equilibrium with respect to security,

wealthand autonomyand the conditionsunder whichalliance formation

and dissolution will be rational. Recall that I originallyassumed the

government'sutilityfunctionto be defined over security,wealth and

autonomy so that U = U (S, W, A). I then assumed that S was itselfa

functionof alliances and armamentsso thatI now have U = U (S (R, L),

W, A).7 I furtherassumed thatthereexisttradeoffsbetweenarmaments

and wealthon the one hand and alliances and autonomyon the other so

thatW = Gi(R) whileA = G2(L). Thus, each governmentcan be expected

to maximizeU subjectto the constraintsof Gi and G2. This is a lagrange

multiplierproblemthefullsolutionto whichcan be found in Appendix 1.

Equilibriumwill occur when the followingtwo conditionsare met:

AU , as

aS aL _ _ dA

dU/aA dL

And

(2) (2) U

au , as

aS dL = _ dW

aU/aw dR

That is, when the ratioof the marginalutilityof alliance to the marginal

utilityof autonomy is equal to the absolute value of the derivativeof

autonomy with respect to alliance and when the ratio of the marginal

utilityof armaments to the marginal utilityof wealth is equal to the

absolute value of the derivativeof welfarewithrespect to armaments.

These conditions,unfortunately, are a bitcomplex forpresentational

purposes but can be simplifiedwithout affectingany major results by

assuming that the rates of transformationbetween alliances and au-

tonomyon the one hand and armamentsand wealth on the other,are

linear.8In thiscase the above conditionsbecome

au as _ u u as _ au

d

aS aL dA aS aR aw

7Clearly, W is itselfalso theresultof a numberof inputs.However,since I am not interested

in the productionof welfareI treatit as a unitarygood.

8The assumption of a linear transformationrate between alliances and autonomy and

betweenarmamentsand welfareis identicalto the assumptionwhichmosteconomists

make of a linear budget constraint.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

528 Western

PoliticalQuarterly

From these conditions,and assuming only substitutioneffects,it can

be seen that it will be rational to forma new alliance in any one of five

circumstances:!'First,if thereis an increase in the marginalproductivity

of alliances. In thiscase the governmentcan be expected to "purchase"

more alliance support thus giving up some autonomy but gaining, in

return,morewealthbyloweringarmamentspurchases.Further,thisshift

fromarmamentsto alliances can be expected to take place at a rate equal

to the RTS of alliances forarmamentsforthatgovernment.This willalso

be thecase ifthegovernment'sutilityforcivilianwealthincreasesor ifthe

marginalproductivity of armamentsdeclines or if the marginalutilityof

autonomy declines. Finally,if the government'sutilityfor securityin-

creases we can expect the governmentto "purchase" both more alliance

supportand more armamentsat the expense of both civilianwealthand

autonomy.

As to the dissolutionof alliances,thiscan also be expected to occur in

any of fivecircumstances:an increase in the marginalproduct of arma-

ments;an increase in the marginal utilityof autonomy; a decline in the

marginalutilityof civilianwealth;a decline in themarginalproductivity of

alliances; or a decrease in the marginalutilityof security.In the firstfour

instancestheincreasedpurchase ofarmamentswillbe accompanied byan

increase in the amount of autonomypossessed by the governmentand a

decrease in civilianwealth.Further,theshiftfromalliances to armaments

willtakeplace at a rateequal to the RTS of armamentsforalliances. In the

fifthcase both armamentsand alliances would be reduced while wealth

and autonomywere increased.

RESEARCH DESIGN

I. The NatureoftheTest

In order fullyto testthetheoryof alliance formationpresentedabove,

I would need to develop measures forthe marginalutilityof security,the

marginalutilityof domesticwealth,the marginalutilityof autonomy,the

marginal product of alliance, and the marginal product of armament.

!' It is,of course, possible,forany of the goods in thisanalysisto be treatedas inferiorto the

point of showing"Giffen"typeeffectsby some governmentsat some times.However,

unlike potatoesor other"market"examples of such goods, it is not at all clear whichof

the goods included in thisanalysiswillbe treatedin thisway by whichgovernmentsat

what times. This will depend on the specificcharacter of each government'sutility

functionwhich,of course, would be difficult to specifyto thisextent.In addition,with

specificregard to alliances (the focusof thisstudy)such instances,to the extentto which

theyoccur at all, are likelyto be veryrare, especiallyamong the major powers. The

reason forthisis thatalliances are two partytrades.The kind of trade resultingfroma

Giffentype effectfor alliances would require one partyto give up autonomy to gain

securitywhiletheothergivesup securityto gain autonomy.This impliestheexistenceof

a veryasymmetrictypeof relationshipsuch as thatbetweena major and minorpower

ratherthanone betweentwomajor powers. For bothof thesereasons I choose to ignore

such possibleeffectsin thisanalysis.I should pointout,however,thatshould such effects

exist forany given trade, thattrade should show up as a mis-predictedcase. Further-

more, if such effectsare common, the theorypresented here will simplynot predict

alliances that formverywell.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 529

Unfortunately, I cannot currentlymeasure mostof theseentities.I have,

however,made some plausible assumptionsabout them. As a result of

these assumptions,I can conduct a limitedtestof the theory.

Recall thatthe conditionsforgovernmentalequilibriuminvolvedfive

terms:dU/&S,aU/BW,aU/aA, aS/IL, and aS/aR. In addition,recall thatI

have assumed thatall of the marginalutilitytermsare alwayspositiveas is

the marginal product of armaments.I also assumed, however,that the

marginalproduct of alliance could be positiveor negative.That is, that

some alliancescould improvea nation'ssecuritywhileotherscould reduce

it. Further,because some autonomy is always lost when any alliance is

made (byassumption)and because the marginalproductof armamentsis

always positive,it can never be rational for a governmentto form an

alliance whichdoes not increase itssecuritysince some increase is always

necessaryto offsetthe loss in autonomywhich is assumed to occur.

As a resultof the above discussion,I can postulatea necessarybut not

sufficient conditionforalliance formationwhichmustbe metpriorto the

meeting any of the fiveconditionsfor formationnoted above. This is

of

the conditionthatthe marginalproduct of the alliance mustbe positive

foreach potentialpartyto the alliance. If thisconditionis not met,then

the alliance cannot form. If it is met, then the alliance may or may not

form,depending on the specificvalues of marginalutilitiesand marginal

productsforeach potentialparticipant.This is the conditionwhichI will

testin the succeeding sectionsof this paper.

I chose, as the spatio-temporaldomain forthistest,alliance formation

among annual European great power dyads during the period 1824-

1900. This domain was chosen forseveralreasons. First,thegreatpowers

werechosen in order to limitthetotalnumberof dyads thatwould have to

be analyzed to a tractablebut interestingset. Also, by limitingthe testto

the great powers the problem of nations being coerced into alliances as

well as that of possible "Giffen"effectswas minimized (see note 8).

Further,by limitingthe test to the European powers I minimized the

effectof any power decay over distance on governmentalcalculations.

Second, the 19th centurywas chosen because I feltthat its Europe-

centered internationalsystemcombined with the fact that the over-

whelmingpreponderanceofcapabilitiesin thatsystemwas in thehands of

the greatpowers would tend to mitigateany distortionscreated by focus-

ing only on alliances among this group of nations.

The startingyear of 1824 was chosen in order to eliminatefromthe

analysisthe dyadic alliances resultingfromFrance's entryintothe Quad-

ruple Alliance in 1818. The reason forthisis thatthe treatyto whichthe

French governmentwas invitedto adhere at Aix-La-Chapelle was not an

ordinarydefense pact but rathera collectivesecurityarrangementcom-

plete with provisions for the pacific settlementof disputes among its

members.One historianhas called thisagreement". . . an experimentin

internationalgovernment. .." (Phillips 1920: 11) whichhe compared to

the League of Nations. Another historianreferred to this alliance as

". .. somethingakin to theUnited Nationsofour own day .. ." (Schmeller

1968: Vol. 1, 11). As a result,therefore,of the unusual nature of this

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

530 Western

PoliticalQuarterly

alliance going, as it did, so far beyond an ordinarydefense pact in its

provisions, I did not feel that the measure I could employ could

adequately capture the calculationsinvolved here.

Finally,the dyad was chosen as the unit of analysisfor purposes of

simplicity.Behind its choice lies the assumption that a governmentwill

consider taking its nation into a multi-lateralalliance only if all other

membersof thatalliance individuallymeetthenecessarycondition.Thus,

I would treat,say,theTriple AlliancebetweenGermany,Austriaand Italy

as three separate alliances between Germanyand Austria,Austria and

Italy,and Germanyand Italy. This assumptionis admittedlysomewhat

simplistic.However, the alternativeassumption,thatgovernmentscalcu-

late whetherthe conditionis met for the alliance as a whole, would have

requiredtheanalysisofall possiblesubsetsofgreatpowerswhichI feltwas

overlyburdensome fora firstcut. In any event,ifthesimplerassumption

provespowerful,theremaybe no need to employthemorecomplexone.

The European great powers and dates of theirstatusas great powers

in the 19thcenturyare given by Singer and Small (1972) as follows:

Country Dates

Austria-Hungary 1816-1900

Prussia/Germany 1816-1900

Russia 1816-1900

France 1816-1900

Italy 1860-1900

United Kingdom 1816-1900

The dependent variableforthisstudyis the formationof new formal

militaryalliances betweendyads of nations.This definitionincludes de-

fense pacts,whichrequire directaid should one partybe attacked; neu-

tralitypacts,whichrequire neutralityshould one partybe attacked; and

ententes,whichrequire onlyconsultationshould one partybe attacked.

This definitionexcludes the upgrading of already existingalliances

due to the larege amount of extra informationwhichsuch partnersare

likelyto have regardingone anothers'capabilities,intentionsand so on. I

feltthatsuch informationwould likelyproduce calculationstoo fineto be

captured by paper indicators.Thus, any dyad whichhas a statushigher

than "no-alliance" is dropped fromconsiderationas long as that status

lasts. For the same reason, I omit considerationof years during which

alliances are maintainedbut not upgraded as instanacesof "alliance."

To illustrateof how these coding rules work, we can examine the

Ententemade betweenAustria-Hungary,Prussia/Germany and Russia in

1833. In principle,thisalliance produces three dyadic alliances: (AUH,

GMY), (AUH,RUS) and (GMY,RUS). However, GMY and AUH already

have a defensepact,stemmingfromtheiralliance in 1815. As a result,this

entente cannot produce a new alliance between them. The only new

alliancesare thosebetweenAUH and RUS and GMY and RUS. Of course,

all of the aformentionedalliances are severed duringthe "yearof revolu-

tion"in 1848. When theyare reconstitutedin 1850, theyare all takento be

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 531

new alliances since the statusof each of the nationsinvolvedvis-a-visone

another was "no alliance" during the preceeding year (1849).

These coding rules produce a data-set of 705 annual dyads for the

period 1824-1900. Of these 705, 9 formdefense pacts,2 formneutrality

pactsand 15 formententeswhile679 formno alliance at all (see Appendix

2 fordyads thatformedand theiryearsof formation).Data on alliances

were obtained fromSmall and Singer (1969) updated by referenceto a

recent (1979) data tape obtained fromthe Correlates of War Project.10

II. MeasuringtheMarginalProductofan Alliance

In order to test the necessarycondition for alliance formationdis-

cussed above I mustprovidean indicatorof the marginalimpactof a new

alliance on a nation's security.This implies, however, that I must first

provide an indicatorof a nation'slevel of securityat any given time. To

accomplishtheserequirements,I draw on theworkof Bueno de Mesquita

(1981). In The War Trap he develops, using a set of assumptions very

similarto those which I have employed here, a theoryof the process by

whichgovernmentschoose to initiatewars.On the basis of thistheory,he

is able to compute a government'sexpected utilityfora war against any

othernation. Furthermore,alliances play a keyrole in thatcomputation.

In particular,Bueno de Mesquita employsa measure based on alliance

commitmentsto obtain indicatorsboth of the utilitywhich the potential

initiatorand opponent have forone another'spositionson relevantissues

as wellas the utilitywhicheach potentialthirdpartyto the war has forthe

issue positionsof the initiatorand opponent (Bueno de Mesquita 1981;

109-18). The theorydeveloped by Bueno de Mesquita proves to be quite

powerfulregardingthe predictionnot only of war initiatonbut also of

dispute escalation,the costsof warsand whichside willachieve victoryin

war.

Using Bueno de Mesquita's theoryof warinitiation,I can compute the

utilitywhicheach governmentof each major power possesses for a war

witheach other major power. I also assume thatthe securityfeltby any

governmentwithregard to any other nation correspondswithits utility

for a war withthat nation. The greatera government'sutilityfor a war

withsome other nation,the more secure thatgovernmentwill feel with

regard to that other nation. I thereforecompute each major power's

overallsecuritylevelto be itsaverage utilityfora warwithanyothermajor

power.

GiventhatI can computeeach major power'soverallsecuritylevel for

each year,I can also computethe marginaleffecton thatsecuritylevelof a

potentialnew alliance foreach potentialparticipantin thealliance. This is

accomplishedby determiningthe effectof the new alliance on the utility

termsof the war initiationchoice calculus of each potentialalliance par-

0As some readers are no doubt aware, there are certaindifferencesbetween the alliance

data as given in Small and Singer (1969) and as given in the up-dated 1979 data-tape

available fromthe Correlatesof War Project.Where these differenceswere relevant,I

used the alliances as given in the 1979 version of thisdata-set.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

532 Western

PoliticalQuarterly

ticipantvis-a-viseach other major power including the other potential

participant.A new securitylevel is then computed for each potential

alliance participantunder the assumption that the alliance is, in fact,

consummated.This new securitylevel foreach participantmay then be

compared to theirsecuritylevelsassumingthatno new alliance is formed

and the potentialchange in securitydue to the new alliance, whichI will

call AS, can be computed foreach potentialparticipant.In order forthe

necessaryconditiondiscussedearlierto be met,the minimumvalue of AS

for each potentialparticipantin a new dyadic alliance must be greater

than zero. That is, there must be some increase in securityto offsetthe

hypothesizedloss of autonomy due to the alliance. A more elaborate

discussionof how securitylevels and potentialchanges in securitylevels

due to potentialnew alliancesare computed maybe foundin Appendix 3.

III. SomePossibleObjections to theMeasure

Before proceedingon to a testof thetheory,itis necessaryto deal with

twoobjectionswhichmightbe raised againstthemeasurementprocedure

described above. First,this measure assumes implicitlythat each major

power perceivesitselfto be equally likelyto go to war againsteach other

major power. It could be argued thatthisis a false characterizationand

that the change in securitydue to an alliance for a given major power

should be computed on the basis of a weighted average withthe weights

corresponding to the with

probabilities which the major powerin question

assigns to wars witheach other power.

The problem here, of course, is how to determinethe weights.What

makes some dyads at some times more war prone than other dyads?

Bueno de Mesquita (1981) offersa partialanswer. In The WarTrap he

pointsout thatthe membersof some dyads ".. . withrespectto general

foreignpolicy ... are not particularlyattentiveto one another" (p. 95).

That is, the securityinterestsof such pairs of nations are just not very

likelyto clash. Further,of those nations whose securityinterestsmay

clash, Bueno de Mesquita showsthatwhethera disputebetweena pair of

nations escalates into a war or not depends heavily on those nations'

respectiveutilitiesforwar withone another (1981: 167-70). In addition,

he also shows thatthisis the case both forallies and enemies. Indeed, he

shows that allies in fact fightdisproportionatelymore often than one

would expect themto by chance (1981: 159-64). Thus, if we assume that

the 19thcenturymajor powersare attentiveto one another,and ifwe also

assume that,under most circumstances,it is verydifficultfor a govern-

mentto predictwell in advance whichothernationsit willand willnot be

engaging in disputes with(and alliances do tend to be long-termaffairs,

see Bueno de Mesquita and Singer 1973), then its only reasonable

strategy,when formingan alliance,is to choose the one whichmaximizes

itssecurityvis-a-visall otherrelevantnationswhethertheyare ostensibly

friendor foe. This is so because, prior to a considerationof utilities,the

nation cannot predictin advance whetherany given dispute whichdoes

arise will be ended favorablyand withoutwar, or not. (Certainlythis is

what Bueno de Mesquita's findingsdiscussed above would imply.)As a

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 533

result,the increase or decrease in a nation'saverage utilityforwar would

appear to be most appropriate here.

A second objection which mightbe raised against the measurement

procedure outlined above is thatalliances provide collectivegoods. As a

result,one partyto thealliance mightreduce itsmilitaryexpenditureand

personnel(2 variablesimportantto the marginalcontributionto security)

once the alliance is made and become a "free-rider"at the other ally's

expense (Olson and Zeckhauser 1966). Thus, this objection goes, the

increasein securitydue to an alliance maywellrest,in part,on therelative

size of the allies and theirtastes.

The problem withthis objection is that the securityprovided by an

alliance only becomes a public good afterthe alliance is formed. Before

thisevent,thepotentialsecurityprovidedbyeach partnerbytheotherare

reallyprivategoods since each partnercan exclude the other fromcon-

sumptionbya simplyrefusingto ally.Once the alliance is concluded, the

public good character of at least some alliance benefitsmightbecome

apparent and individual productiondecisions mightchange as a result.

However, under the assumptionof Cournot typeindividualism,neither

partyshould calculate that anythingwill be differentafterthe alliance

thanitwas beforetheallianceexceptthealliance. Since myanalysisis not

concerned with what happens after the alliance is formed I need not

include such elementsas "size" or "taste"in my measure. I mightpoint

out, though, that should one partner'sarmamentsdrop so low that its

worthas an alliance partnerdrops below itscost in lost autonomyto the

other partner, it would be rational for that other partner simply to

abrogate the alliance therebyonce again excluding the delinquent part-

ner fromconsumptionof the alliance good. This line of reasoningwould

seem to implythat,even afterformation,alliance goods are not wholly

public in character.Indeed, some evidence existsforthisviewin NATO.

In his examinationof Olson and Zeckhauser'sempiricalfindings,Francis

Beer (1972: 23) notes that

... the evidencefromNATO does not firmly supportOlson and Zec-

khauser'shypothesis of thegreatbythesmall..."

of "theexploitation

Nordo thedatanecessarily implythatthe"largera nationisthehigherits

valuationof theoutputof an alliance."

TESTING THE THEORY

I. TestingtheNecessaryCondition

Having now developed an indicatorof the marginal product of an

alliance, I can proceed directlyto a test of the necessarycondition for

alliance formationdiscussed above. To testthisconditionI separated the

These notions are, of course, perfectlyconsistentwith each party to a new alliance

expectingto be able to loweritsownarmslevelonce thealliance is made. Whatis barred is

eitherpartythinkingthatthe otherone expects to reduce itsarms level. These notions

are admittedlyverysimple-minded.However, as I have noted previously,theyhave

proven powerfulin similarcontexts.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

534 Western

PoliticalQuarterly

705 dyads in my data-setinto two groups. In one group the minimum

value of AS forboth membersof the dyad was greaterthan zero. In the

other group, the minimumvalue of AS was less than or equal to zero. I

then examined the two groups to determine how many dyads in each

group formeda new alliance. Before presentingthe resultsof thattest,

however,some discussion of the nature of necessarybut not sufficient

conditionsis in order.

To state that X is a necessary but not sufficientcondition for the

occurenceof Y is to statethat,if X occurs,thenY can but need not occur.

However, if X does not occur, then Y cannot occur. This is the same as

statingthatY is a sufficientconditionforX. In the contextof the current

analysis, this means that, if each party to an alliance experiences an

increase in securitydue to the alliance (the "X" condition),then the two

partiescan but need not ally(the "Y" condition).On the otherhand, ifat

leastone of thepartiesto thepotentialalliance achievesno gain in security

(or suffersa loss), then an alliance cannot take place.

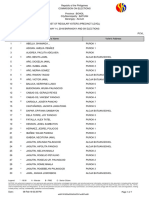

Figure 1 showsthenatureof thisconditionin a moregraphicmanner.

FIGURE 1

Minimum Minimum

AS>O AS<O

Form A

Alliance

Do Not C D

Form

Alliance

The columns of the contingencytable representthe values of the inde-

pendentvariable,whetheror notthe minimumvalue of ^S is greaterthan

zero. That is, whetheror not the necessaryconditionforalliance forma-

tion is met. The rows representthe values of the dependent variable,

whether or not an alliance was formed. The statementmade by the

necessarycondition derived earlier is simplythis; that the shaded cell

should be empty.Nothingat all is said regardingthe distributionof cases

in the other three cells. In particular, nothing is said regarding the

distributionof cases as between cells C and D. Of course, if cell D were

emptyand all of the cases whichfailed to formalliances resided in cell C

then,even iftherewere no cases at all in cell B, thisfindingwould not be

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 535

veryinterestingsince it would not help us rule out any dyads at all as

possibleallies. On theotherhand, giventhe natureof theconditionbeing

tested,it would also probablybe too much to expect thatcell C would be

empty.Finally,given the grossness of the measures involved, it would

probablyalso be too much to expect cell B to be totallyempty,though it

should be "almost" empty.

This discussion raises a number of questions regarding how the re-

lationshippostulatedhere can be adequately tested.The onlycases which

are trulymis-predictedbythisconditionare thosewhichshowup in cell B.

On the other hand, we would also like to be able to say something

regardingtheusefulnessof thecondition.Usefulness,in turn,restson the

abilityof the conditioneffectively to rule out some "reasonable" fraction

of thecases as potentialalliance partners.One wayto testthisrelationship

would be throughthe use of predictionanalysis(Hildebrand, Laing and

Rosenthal 1976). However, this technique has not been widelyused in

politicalscience and may be unfamiliarto manyreaders. Instead, I have

chosen to employtwowidelyused meaures of"goodness-of-fit." The first

of theseis Yule's Q. This is a measure of associationespeciallywell suited

for use witha necessarybut not sufficient condition. It is computed as

(A*D)- (B*C)

(A*D) + (B*C)

As the reader will note, this statisticcan achieve unityif only one cell is

empty rather than the usual two which would be required for other

statisticssuch as Tau-b.

The second measure of goodness-of-fit I willemployis a simpleT-test

forthe significanceof the differenceof twoproportions.This testwillbe

used to determinewhetherthe proportionof dyads whichformalliances

among those failing to meet the necessary condition (ideally zero) is

significantlysmaller than the proportionof dyads which formalliances

among those meetingthe necessarycondition(a numberabout whichthe

conditionitselfsays nothing).

The resultsof the data analysisare displayedin Figure 2. theseresults

generallyconfirmmyexpectationsforthenecessaryconditionforalliance

formationderived from the theory.Of the 566 dyads which meet the

conditionof positivegain in securityforbothpotentialpartners,24 or 4.2

percentformallianceswhile,of the 139 dyads whichfailto meetthismost

basic condition, only 2 or 1.4 percent form new alliances. Thus, the

formationrate among dyads whichmeet the conditionis threetimesthe

rateamong dyads whichfailto meetit.The testforthe significanceof the

differenceof proportionsindicatesthatthisresultcould occur bychance

fewerthansix out of one hundred times.In addition,Yule's Q computed

on this table yieldsa value of .504, indicatinga fairlystrongdegree of

association. As to the substantivevalue of the condition,it successfully

rulesout,as possiblecandidatesforalliance formation,over 20 percentof

those dyads whichactuallyfail to formwhile incorrectlyrulingout only

about 8 percent of those which do form.This is a far more successful

resultthan any obtained by those who have studied alliance as a systemic

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

536 Western

PoliticalQuarterly

FIGURE 2

Minimum Minimum

AS>O AS<0

Form 24 2 26

Alliance

Do Not 542 137 679

Form

Alliance

566 139

Yule's Q = .504

Z = 1.57 Sig. at < .06

phenomenon. Finally,the twocases of dyads formingalliances in spiteof

theirmeasured violationof theconditionwereratherunusual. Both arose

fromItalyjoining the Triple Alliance. In each case, Italy gains dramat-

icallyfromthealliance,increasingitssecurityby88 percentwithGermany

and by 77 percentwithAustria. The Dual Allies, however,were by my

measure losers, withGerman securityreduced by 17 percentand Aust-

riansecurityreduced by 18 percent.Why,then,was Italybroughtintothe

alliance? The answerseems to be thatBismarkcalculated that,whileItaly

would be worthlessto the Dual Alliance if not an outrightburden, the

Italians could constitutea major threatto the Germanic coalition were

theyto fallintoan alliance withthe French.As Langer (1950; 244) put it:

... Bismark... wrotetoViennastressing

. .. that,inan alliancewithItaly

theformof theagreement wasofverylittleimportance. The mainthing

was to secure Italian neutrality. . . Germany and Austria did not need

Italianhelpand did notexpectit.Alltheywantedwastheassurancethat

Italywouldnotbe antagonisticand in thatwaytieup valuableAustrian

forceson theAustro-Italian

Frontier.

Indeed, by my measure, were Italy to have allied with France in 1882

instead of Germany and Austria, France's securitywould have been

increased by 15 percent while Italy's would have been increased by 47

percent.Thus, bymymeasure,Bismarkwas correctin thatItalydoes add

to Frenchsecurity.However,he mayhave been incorrectin assessingthe

magnitudeof thataddition. Thus, whatwe may have here is a mispredic-

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 537

tionas theresultofa game-theoreticassessmentof thevalue ofdenyingan

alliance to an enemy.

Another way to view these cases, however, is that they represent

instancesof Giffen-type effects.Bismark,under thisinterpretation,was

prepared to giveup some securityin order to gain some controlover what

the Italiansmightdo ifwar did breakout and thusincreasehis freedomof

actionvis-a-visotherpowers,especiallyFrance. This interpretationgains

some credibility fromthe factthatItalywas theweakestof thepowersand

did give up some of itsambitionsto secure the alliance (Langer 1950; ch.

7). Unfortunately,which of these interpretationsis the more correct

cannot be determined withouta thorough reading of documents and

diaries,whichwould be beyond the scope of thispaper. Whatcan be said,

however,is thatthese twocases appear to be the onlyones of theirtypein

the data.

II. SomeSpeculationon Sufficient Conditions

The theory,insofar as it as been tested here, appears to be well

supported by the available data. The next step, of course, is to begin to

develop measures which would allow for the testingof sufficient condi-

tionsforalliance formation.The utilityterms,of course, willprobablybe

verydifficult to assess. However,itmightbypossibleto assessthemarginal

productof armamentsas wellas, and especially,thecostof givenalliances

in termsof lost autonomy.To show how thiscould improve prediction,

note that,of the 542 cases in cell C, about 5 percent(or 27 dyads) involved

France and Germanyduring the period 1870-1899 inclusive.In each of

thosepotentialalliancesFrance would have been thegreatestgainer.Such

an alliance, however,would no doubt at least have required the French

governmentto accept the German regime in Alsace-Lorraine,a loss of

autonomywhich that governmentsimplycould not accept.

III. Extensions of theTheory

The reader will note that the theorypresented here does not just

purport to explain alliance formation.It is really a theoryabout the

trade-offs whichexistfora governmentbetweenarmamentsand alliances

as sources of security.As a result, the theoryshould not only tell us

somethingabout thedecision to ally,itshould also tellus somethingabout

the decision to procure armaments,as well,and, in addition, something

about the trade-offswhichexist between the two methods of increasing

securitydiscussed here and the othercommodities(domesticwealthand

autonomy)whichgovernmentsmayalso wantto consume. A futurepaper

willattemptto measure these trade-offs, as theyoccur, forspecificcoun-

triesover timesince,using thatapproach, marginalutilitiesas wellas the

"costs" of alliances in termsof lost autonomy may be measureable.

Even as it stands,however,the theorycan tell us a few thingsabout

thesetrade-offs.First,it would seem thatmajor powers,because theyare

so powerful,should have available to themonlya verylimitednumberof

alliance partnerswho can increasetheirsecurity.Once these partnersare

exhausted,such nations,iftheywishto furtherincreasetheirsecurity,will

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

538 PoliticalQuarterly

Western

findthemselvesforcedto depend on armaments,thusgivingup domestic

wealth.Major powerswhose governmentshave highutilityforautonomy

will find themselvesin this position even sooner. Thus, if two major

powers each findsthe other to be its main securityconcern,and if both

have exhausted their securityenhancing alliances, we would have the

beginningsof an arms race. On the other hand, should such alliances be

unused at the time concern over securitydevelops, and if both powers

have low utilityfor autonomy,we mightsee an "alliance race" develop

until such time as the exhaustion of allies takes place or sufficientau-

tonomyis lost so as to make the loss of domestic wealth attendant to

increased armamentspreferableto furtherlosses in autonomy.

Even minor powers may findthemselvesdepending a great deal on

armamentsif theyhave high utilityfor autonomy.This is because their

major power friends,if theyhave any (nations like the Ayatollah'sIran

may value autonomyso highlythat no alliance looks attractive),may be

unwillingto aid them in circumstancesnot of interestto those friends.

One example of thisis the attitudeof the United States toward French

interestsin Africa.Historically,the United Statesdeclared itswillingness

to aid France up to and includingthe use of nuclear weapons on itsbehalf

in the event of an attackon France by the Soviet Union. On the other

hand, the US was quite unwillingto aid (and sometimesopposed) France

in Africa,especially when what the French governmentwas tryingto

accomplishtherewas different fromtheoutcome preferredbythe United

States.

CONCLUSION

This paper has presented a theoryof the process by which national

governmentschoose to formmilitaryalliances and has testeda necessary

but not sufficient conditionderived fromthattheory.Further,the results

of thattesthave been about as supportiveof thetheoryas theycould have

been given the nature of the condition being tested.

Clearly,much more workneeds to be done in thisarea. However, the

analysis presented here does offerreasonable support for the simple

micro-economicapproach adopted in this paper.

Finally,as I notedearlier,mostrecentstudiesof alliance behaviorhave

been carried out at the systemiclevel. Further,such studies have found

thedistributionof alliancesto be essentiallyrandom over time.This study,

however,indicatesthatwhen alliances are viewed cross-sectionally at the

nation-statelevel theydo not appear to be random but instead followa

definite pattern; i.e., potential alliances which fail to increase both

partners'securitylevels almost never form.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 539

APPENDIX 1

Solution of the Constrained

MaximizationProblem

To summarize,I have stated the followingrelationships:

Maximize: U = U(S, W, A) subject to

1: S = S(L, R)

2: W= G1(R)

3: A = G2(L)

For convenience,I will temporarilyignore the interveningvariable S and write

U = U(L, A, R, W) then the Lagrangian becomes...

V = U(L, A, R, W) + Xi*(W - G, (R)) + X2*(A - G2(L))

AND

4: aV/0L = aU/aL + (X2- - dA/dL)

5: aV/aA = aU/aA + X2

6: 'V/aR = aU/aR + (Xi - dW/dR)

7: aV/aW= au/aW+ Xi

Settingthese four equations equal to zero and performingsome algebra I get

8: aU/aL = X2 * dA/dL

9: aU/aA = -A2

10: aU/aR = XA? dW/dR

11: aU/lW= --l

Dividing 8 by 9 and 10 by 11 I get the equilibriumconditions

12: aU/aL _ -dA

aU/aA dL

13: R

aU//R -dW

aU/ia dR

But recall that, by the chain rule,

au a

a_U

_ 0

as and au U aS

aL aS aL aR aS aR

so that 12 and 13 become

14: au aS

aS aL -dA and

aU/aA dL

15: au aS

as aR -dW

aU/aR dR

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

540 PoliticalQuarterly

Western

APPENDIX 2

New Dyadic Alliances Among European

Major Powers, 1824-1900

Year Dyad Alliance

1827 UK, FRN Entente

1827 UK, USR Entente

1827 FRN, USR Entente

1833 GMY, USR Entente

1833 AUH, USR Entente

1834 UK, FRN Defense Pact

1840 UK, GMY Defense Pact

1840 UK, AUH Defense Pact

1840 UK, USR Defense Pact

1844 UK, USR Entente

1850 GMY, AUH Defense Pact

1850 GMY, USR Entente

1850 AUH, USR Entente

1861 UK, FRN Entente

1863 GMY, USR Defense Pact

1873 GMY, AUH Entente

1873 AUH, USR Defense Pact

1881 GMY, USR NeutralityPact

1881 AUH, USR NeutralityPact

1882 GMY, ITA Defense Pact

1882 AUH, ITA Defense Pact

1887 UK, AUH Entente

1887 UK, ITA Entente

1891 FRN, USR Entente

1897 AUH, USR Entente

1900 FRN, ITA Entente

APPENDIX 3

Bueno de Mesquita (1981) computes nationi's utilityfora waragainstnationj

as:

E(Ui) = E(Ui)b + 2E(Ui)ki

where E(Ui)b representsi's utilityfor a bi-lateralwar withj and EE(Ui)ki

k

representsthe totalamount of aid or opposition whichi expects to receive from

potentialthird-parties,k, to the war.

Furthermore:

E(Ui)b = Pi(Uii - Uij) + (1-Pi)(Uij - Uii)

where:

Pi is i's perceptionof the probabilitythat i wins the bilateralwar withj.

(I-Pi) is i's perceptionof the probabilitythat i loses the bilateralwar withj.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The DecisiontoAlly:A Theoryand Test 541

Uii is i's utilityfor its own policypositions.

and,

Uij is i's utilityforj's policypositions.12

Further,

Pi is measured as the ratioof i's capabilitiesto the sum of i's andj's capabilities

as measuredbytheCorrelatesof War project'scompositecapabilityscoreindex. 3

Uii is assumed to be 1.

Uij is measured as the rank order correlation (Tau-b) between i's and j's

alliance statuseswithone anotherand all othernationsin theregion.As discussed

in Bueno de Mesquita (1981: 94-97, 109-18), thisis computed by firstranking

alliancesfromthe mostrestrictive of a nation'sautonomy(a defense pact),to least

restrictive(a status that might be called "no alliance"). This ranking is then

employed to create a 4x4 table forthe pair of nations,i and j, and thencorrelate

theirstatuseswithone anotherand all third-parties in the region.'4 Of course, ifi

changesanyof itsalliance statuses,themeasured value of Uij willalso change. As a

result,the measured value of E(Ui)b will also change, either increasingor de-

creasing i's utilityfor the bi-lateralwar withj.

Having completed the explanation of how E(Ui)b is computed, we can move

on to a discussionof how SE(Ui)ki is computed.

k

Bueno de Mesquita (1981; 58) computesEE(Ui)ki at anygiventimeas follows:

[(Pik + Pjk - 1) * (Uiki - Uikj)]

where:

Pik is i's perceptionof the probabilitythati wins the war withj, given that k

joins i.

Pjk is i's perceptionof the probabilitytllati loses the war withj, given thatk

joins j.

Uiki is i's perception of k's utility for its policy positions.

Uikj is i's perception of k's utility for j's policy positions.

12 Inhis discussionof E(Ui) Bueno de Mesquita includes termsfori's perceptionof antici-

pated changes in the value of Uij as wellas changes in the values of Uiki and Uikj, to be

discussed below. Although these terms are importanttheoretically,they cannot, at

present,be measured in any systematicfashion.As a result,I disregard them here.

3In his measurementof the probabilitytermsused in the calculationof utility,Bueno ide

Mesquita employsa correctionfor distance when measuringcapabilities(and, there-

is notemployedherebecausethemajorpowersin

Thiscorrection

fore,probabilities).

the European regionare close enough to one anotherso thatthiscorrectionneed notbe

employed. I thereforedisregarddiscussionof thiscorrectionhere. Indeed, one of the

in

reasons for choosing the European major powers was to avoid the extra difficulty

fordistancewouldhaveadded to an alreadycomplex

whichcorrecting

computation

procedure. Also, it should be noted that,whiledyads are measured annuallyalthough

data on capabilitieswas available onlyquinquennially,I employeda linearextrapolation

toobtainapproximations

ofannualcapabilities.

Forexample,theUK'sscoreisgivenas

28.2 in 1820 and 27 in 1825. Thus, itsannual scoresfor 1821 to 1824 wereassumed to be

27.96, 27.72, 27.48 and 27.24 respectively.

4

"TheEuropean regionis definedhere as in Bueno de Mesquita (1981: 94-97) except thatI

assume China to be a memberof thatregionas of 1895 so thatitsalliance withRussia can

be takenintoaccountin computing

theutility

measures.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

542 WesternPolitical Quarterly

Anid,

Pikis measured as theratioof thesum of i's and k'scapabilitiesto thesum of i's,

k's and j's capabilities.

Pjk is measured as the ratioof the sum of k's and j's capabilitiesto the sum of

k's,j's and i's capabilities.

Uiki is measured as the rank order correlationbetween i's and k's alliance

statuseswithall nations in the region includingeach other.

Uikj is measured as the rank order correlationbetweenj's and k's alliance

statuseswithall nations in the region includingeach other.

Thus, again, any change in i's alliance statuseswillbe reflectedin a change in

the measured value of Uiki and will thus result in a change in the measured

amountofaid or oppositionwhichi can expectto receivefromeach kin a warwith

j; thatis, it will resultin a change in the measured value of .E(Ui)ki.

k

Having now explained how a nation'sutilityforwar withsome othernationis

computed, I can state the definitionof securityemployed in this paper.1'

The overall securitypositionof each major power is simplyitsaverage utility

for a war against all other major powers in the European region. This average,

designated S, is computed as:

n-I

E E(Ui)j/(N- 1)

j= 1

Where N is the numberof major powersin theEuropean region'; and eachj is

a major power which i mighthave to fight.

In order to compute AS, the change in a nation'ssecuritydue to a proposed

newalliance,I assume the newalliance to have been made and determinehow that

change in foreignpolicyaffectsS throughitsaffectson Uij, Uiki and Uikj.17The

I' In computingE (Ui) Bueno de Mesquitaincludescorrections foruncertainty and risk-

takingbehavior.MajorPowersare assumedto behaveas iftheywererisk-acceptant

Underconditions

underbothriskand uncertainty. of risk.all thirdparties'potential

tothewarareincludedinthecomputation

contributions oftE(Ui)ki.Underconditions

of uncertainty,only those third parties for whom Uiki>O and Uikj<O or for whom

Uiki<0 and Uikj>0 are includedin thiscomputation.These correctionsareemployedin

thisstudy.Discussionof themhas been omittedfromthetext,however,so as notto make

an already complex discussioneven more so. The reader who is interestedenough to

havecomethisfarshouldsee Buenode Mesquita( 1981:59-64)fora discussion

ofthis

rule.

I'iIn assessingeach greatpower'ssecurity,I calculate itssecurityonlyagainsttheothergreat

powers. Further,when computingeach greatpower's utilityforwar againsteach other

great power, I only consider the aid which each side may receive fromother great

powers.I do thisbecause(a) I assumethatminorpowerssimplycannotdo muchto

affectthe outcome of a major power war and, (b) I assume thatalliances made among

the great powers are directed primarilyagainst the other great powers.

7In computing due toa newalliance,I adoptthefollowing

thechangeinsecurity conven-

tions:

is alwaysa defensepact.Thisis

(a) I assumethatthenewalliancebeingcontemplated

because thedefensepactresultsin thegreatestincreasein themeasured utilitywhichthe

twopartieshave foreach other'spolicypositions.It should, therefore,offerthe greatest

marginal increase in securityto the parties.

(b) In computinga nation'ssecurityafterthe assumed formationof a new alliance, I

take intoaccount the nation'sutilityforwar againstall othergreat powers includingits

potentialally. I do thisbecause, as I have already noted, allies tend to fightfar more

often than one would expect by chance.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Decision to Ally: A Theoryand Test 543

necessarybut not sufficientconditionforthe formationof such a new alliance is

that AS be positivefor both potentialallies.

REFERENCES

Altfeld,Michael F. 1979. "The Reactions of Third States Toward Wars." Ph.D.

Dissertation,Universityof Rochester.

, and Bruce Bueno de Mesquita. 1979. "Choosing Sides in Wars."Interna-

tionalStudiesQuarterly23: 87-112.

Allison, Graham, and Morton H. Halperin. 1972. "Bureaucratic Politics: A

Paradigmand Some PolicyImplications."In RaymondTanter and RichardH.

Relations.Princeton:Princeton

and Policyin International

Ullman, eds., Theory

UniversityPress.

Beer, FrancisA. 1972. ThePoliticalEconomyofAlliances:Benefits,

Costsand Distribu-

tionsin NATO. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Becker, Gary S. 1971. EconomicTheory.New York: Knopf.

Berkowitz,Bruce. 1983. "Realignmentin InternationalTreaty Organizations."

InternationalStudiesQuarterly27: 77-96.

Buchanan, James M. 1969, Costand Choice.Chicago: Markham.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce. 1975. "Measuring SystemicPolarity."Journal ofCon-

flictResolution19: 187-216.

1981. The War Trap. New Haven: Yale University Press.

,andJ. David Singer. 1973. "Alliances,Capabilitiesand War: A Reviewand

Synthesis."In Cornelius P. Cotter,ed., PoliticalScienceAnnual. New York:

Bobbs-Merrill.

Fellner, William. 1949. Competition AmongtheFew. New York: Knopf.

Henderson, James M., and Richard E. Quandt. 1980. Microeconomic Theory.New

York: McGraw-Hill.

Hildebrand, David K.,JamesD. Laing, and Howard Rosenthal. 1976. "Prediction

Analysis in Political Research." AmericanPoliticalScienceReview 70, No. 2:

509-35.

Job, Brian L. 1976. "Membershipin Inter-NationAlliances, 1815-1965: An Ex-

plorationUtilizingMathematicalProbabilityModels." In Dina A. Zinnes and

John V. Gillespie, eds., Mathematical Modelsin International

Revelations.New

York: Praeger.

Langer, William. 1950. EuropeanAlliancesand Alignments. New York: Knopf.

Liska, George. 1968. Nationsin Alliance.Baltimore:Johns Hopkins Press.

McGowan,PatrickJ.,and RobertM. Rood. 1975. "AllianceBehavior in Balance of

Power Systems:Applyinga Poisson Model to NineteenthCenturyEurope."

AmericanPoliticalScienceReview69: 859-70.

McGuire,Martin.1965. Secrecy and theArmsRace. Cambridge: Harvard University

Press.

.1974. "Group Size, Group Homogeneityand theAggregateProvisionof a

Pure Public Good Under Cournot Behavior." PublicChoice 18: 107-26.

. 1982. "U.S. Assistance and Israeli Allocation." Journal of ConflictReso-

lutions26: 199-235.

Murdoch,James,and Tood Sandler. 1982. "A Theoreticaland EmpiricalAnalysis

of NATO."Journal of Conflict

Resolution26: 237-63.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

544 WesternPolitical Quarterly

Olson, Mancur, and Richard Zeckhauser. 1966. "An Economic Theory of Al-

liance." ReviewofEconomicsand Statistics 48: 266-79.

Organski, A. F. K. 1962. World Politics,2nd ed., New York: Knopf.

Phillips,Walter Alison. 1920. The Confederation ofEurope. London: Longmann.

Rosen, Steven. 1970. "A Model of War and Alliance." In Julian R. Friedman,

ChristopherBladen, and Steven Rosen, eds., Alliancesin InternationalPolitics.

Boston: Allynand Bacon.

Russett,Bruce M. 1968. "Componentsof an Operational Theory of International

Alliance Formation."Journalof Conflict Resolution12: 285-301.

Schmeller, Kurt R. 1968. Hall and Davis' The CourseofEuropeSinceWaterloo.New

York: MeredithCorporation.

Sen, Amartya K. 1970. CollectiveChoice and Social Welfare.San Francisco:

Holden-Day.

Singer,J. David, and MelvinSmall. 1968. "Alliance Aggregationand the Onset of

War, 1815-1945." In J. David Singer, ed., ()uantitativeInternationalPolitics.

New York: The Free Press.

, Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey. 1972. "Capability Distribution, Uncer-

tainty,and Major Power War, 1820-1965." In Bruce M. Russett,ed., Peace,

War,and Numbers.BeverlyHills: Sage.

, and Melvin Small. 1972. The Wages of War 1816-1965: A StatisticalHand-

book.New York: Wiley.

Siverson, Randolph M., and George T. Duncan. 1976. "Stochastic Models of

InternationalAlliance Initiation: 1885-1965." In Dina A. Zinnes and John V.

Gillespie, eds., MathematicalModels in InternationalRelations. New York:

Praeger.

Small, Melvin, and J. David Singer. 1969. "Formal Alliances, 1816-1965: An

Extension of the Basic Data." JournalofPeace Research6: 257-82.

This content downloaded on Wed, 19 Dec 2012 10:59:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Você também pode gostar

- Finding Images in Visual SearchDocumento11 páginasFinding Images in Visual SearchEvans LoveAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison of CEP Estimators for Elliptical Normal ErrorsDocumento20 páginasComparison of CEP Estimators for Elliptical Normal ErrorsjamesybleeAinda não há avaliações

- Disruptive Military Technologies - An Overview - Part IIIDocumento6 páginasDisruptive Military Technologies - An Overview - Part IIILt Gen (Dr) R S PanwarAinda não há avaliações

- Argument Mapping ExerciseDocumento2 páginasArgument Mapping ExerciseMalik DemetreAinda não há avaliações

- Joint Pub 3-08 Interorganizational Coordination During Joint Operations, 2011, Uploaded by Richard J. CampbellDocumento412 páginasJoint Pub 3-08 Interorganizational Coordination During Joint Operations, 2011, Uploaded by Richard J. CampbellRichard J. Campbell https://twitter.com/Ainda não há avaliações

- UT 4 Lectura Recomendada 20061001 Structured Analysis of Competing Hypotheses - Wheaton ChidoDocumento4 páginasUT 4 Lectura Recomendada 20061001 Structured Analysis of Competing Hypotheses - Wheaton ChidoRodrigo Spaudo CarrascoAinda não há avaliações

- An PVS-14Documento2 páginasAn PVS-14ArmySGT100% (1)

- OODA Applied To C2Documento22 páginasOODA Applied To C2Lou MauroAinda não há avaliações

- How Col. John Boyd Beat The GeneralsDocumento3 páginasHow Col. John Boyd Beat The GeneralsMartin Edwin AndersenAinda não há avaliações

- Future Warfare Hybrid WarriorsDocumento2 páginasFuture Warfare Hybrid WarriorsCarl OsgoodAinda não há avaliações

- NATO IO Reference PDFDocumento118 páginasNATO IO Reference PDFCosti MarisAinda não há avaliações

- FDR's First Inaugural Address: A Rhetorical Analysis of His Use of Ethos, Pathos and LogosDocumento10 páginasFDR's First Inaugural Address: A Rhetorical Analysis of His Use of Ethos, Pathos and LogosLauraAinda não há avaliações

- Sidwell Robert WilliamDocumento145 páginasSidwell Robert Williamcarolina maddalenaAinda não há avaliações

- Yarger Chapter 3Documento10 páginasYarger Chapter 3BenAinda não há avaliações

- 96.1 (January-February 2016) : p23.: Military ReviewDocumento7 páginas96.1 (January-February 2016) : p23.: Military ReviewMihalcea ViorelAinda não há avaliações

- Operational Art Requirements in The Korean War: A Monograph by Major Thomas G. Ziegler United States Marine CorpsDocumento56 páginasOperational Art Requirements in The Korean War: A Monograph by Major Thomas G. Ziegler United States Marine CorpsЕфим КазаковAinda não há avaliações

- Dangers of Over-Reliance on TechnologyDocumento76 páginasDangers of Over-Reliance on TechnologyHường NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Raytheon Annual Report 2017Documento162 páginasRaytheon Annual Report 2017juanpejoloteAinda não há avaliações

- RR1737-Structured Simulation-Based Training ProgramDocumento259 páginasRR1737-Structured Simulation-Based Training ProgrambsuseridAinda não há avaliações

- (1 - Assessing and Strengthening The Manufacturing and Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain Resiliency PDFDocumento146 páginas(1 - Assessing and Strengthening The Manufacturing and Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain Resiliency PDFLurzizareAinda não há avaliações

- Oplaw HDBKDocumento665 páginasOplaw HDBK...tho the name has changed..the pix remains the same.....Ainda não há avaliações

- Neither Star Wars Nor Sanctuary Constraining The Military Uses of Space 2004Documento191 páginasNeither Star Wars Nor Sanctuary Constraining The Military Uses of Space 2004Lexa22Ainda não há avaliações

- 21st Century NS ChallengesDocumento420 páginas21st Century NS ChallengesfreejapanAinda não há avaliações

- Boyds Big Ideas 1Documento399 páginasBoyds Big Ideas 1ad9292Ainda não há avaliações

- Measure PowerDocumento34 páginasMeasure PowerMohamad Noh100% (1)

- Disruptive technologies and nuclear weapons in an era of political instabilityDocumento6 páginasDisruptive technologies and nuclear weapons in an era of political instabilityLuca Capri100% (1)

- China-ASEAN Relations Strained by South China Sea DisputeDocumento19 páginasChina-ASEAN Relations Strained by South China Sea DisputeNur AlimiAinda não há avaliações

- JCS and National Policy in the Early 1960sDocumento396 páginasJCS and National Policy in the Early 1960sFede Alvarez LarrazabalAinda não há avaliações

- NASA Responses To Trump Transition ARTDocumento94 páginasNASA Responses To Trump Transition ARTJason Koebler100% (1)

- NGB-LL Analysis - Fy12 NdaaDocumento14 páginasNGB-LL Analysis - Fy12 NdaaJacob BernierAinda não há avaliações

- China's Space AmbitionsDocumento27 páginasChina's Space AmbitionsIFRIAinda não há avaliações

- Manpads Attacks On Civilian AircraftDocumento160 páginasManpads Attacks On Civilian AircraftSMJCAJRAinda não há avaliações

- Communication Power and Counter Power in The Network Society PDFDocumento2 páginasCommunication Power and Counter Power in The Network Society PDFLazarAinda não há avaliações

- Bitdefender In-Depth Analysis of APT28-the Political Cyber-EspionageDocumento26 páginasBitdefender In-Depth Analysis of APT28-the Political Cyber-Espionagekpopesco100% (1)

- Lost in Space: A Realist and Marxist Analysis of US Space MilitarizationDocumento26 páginasLost in Space: A Realist and Marxist Analysis of US Space MilitarizationBrent CooperAinda não há avaliações

- Coccp 2016-28Documento77 páginasCoccp 2016-28En MahaksapatalikaAinda não há avaliações

- The Light Infantry Division Regionally Focused For Low Intensity ConflictDocumento317 páginasThe Light Infantry Division Regionally Focused For Low Intensity Conflictmihaisoric1617Ainda não há avaliações

- HEL AdvancesDocumento8 páginasHEL Advancesbring it onAinda não há avaliações

- Power LasersDocumento9 páginasPower LaserszufarmulAinda não há avaliações

- Doctrine Uk Air Space Power JDP 0 30Documento138 páginasDoctrine Uk Air Space Power JDP 0 30pangolin_79Ainda não há avaliações

- Linear Thinking Vs Lateral ThinkingDocumento15 páginasLinear Thinking Vs Lateral ThinkingAyush JainAinda não há avaliações

- AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE PUBLICATION INFORMATION OPERATIONS PLANNING MANNUAL - DraftDocumento86 páginasAUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE PUBLICATION INFORMATION OPERATIONS PLANNING MANNUAL - DraftMatt100% (2)

- Russian National GuardDocumento15 páginasRussian National GuardThe American Security ProjectAinda não há avaliações

- Strategic Culture A.I. JohnstonDocumento34 páginasStrategic Culture A.I. JohnstonIulia PopoviciAinda não há avaliações

- Chemical Warfare Agents ResearchDocumento55 páginasChemical Warfare Agents ResearchMohd Zulhairi Mohd NoorAinda não há avaliações

- Dictionary of Military TermsDocumento503 páginasDictionary of Military TermsAccuWordsTransAinda não há avaliações

- Commander's Handbook Strategic Communication Communication StrategyDocumento232 páginasCommander's Handbook Strategic Communication Communication StrategyChioma MuonanuAinda não há avaliações

- Revolution in Military Affairs - 1990 Up To The PresentDocumento61 páginasRevolution in Military Affairs - 1990 Up To The PresentBen SteigmannAinda não há avaliações

- The Soviet Response to the Downing of KAL Flight 007Documento116 páginasThe Soviet Response to the Downing of KAL Flight 007Greg JacksonAinda não há avaliações

- Social Mood and Elliott Waves Predict Historical PatternsDocumento16 páginasSocial Mood and Elliott Waves Predict Historical Patternsfreemind3682Ainda não há avaliações

- Asymmetrical Warfare and International Humanitarian Law.Documento41 páginasAsymmetrical Warfare and International Humanitarian Law.Zulfiqar AliAinda não há avaliações

- CHEM 137.1 Full Report TemplateDocumento2 páginasCHEM 137.1 Full Report TemplateOnoShiroAinda não há avaliações

- DoD Directive 3000.07 IWDocumento14 páginasDoD Directive 3000.07 IWDave DileggeAinda não há avaliações

- Military Radars: Raghu Guttennavar 2KL06TE024Documento23 páginasMilitary Radars: Raghu Guttennavar 2KL06TE024Shreedhar Todkar100% (1)

- Coalition Management and Escalation Control in a Multinuclear WorldNo EverandCoalition Management and Escalation Control in a Multinuclear WorldAinda não há avaliações

- Gangs in the Caribbean: Responses of State and SocietyNo EverandGangs in the Caribbean: Responses of State and SocietyAnthony HarriottAinda não há avaliações

- Space Electronic Reconnaissance: Localization Theories and MethodsNo EverandSpace Electronic Reconnaissance: Localization Theories and MethodsAinda não há avaliações

- On Target: Bible-Based Leadership for Military ProfessionalsNo EverandOn Target: Bible-Based Leadership for Military ProfessionalsAinda não há avaliações

- Balkan Nationalism WWIDocumento2 páginasBalkan Nationalism WWIdragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Cultural Views on Normal and AbnormalDocumento2 páginasCultural Views on Normal and Abnormaldragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Balkan Nationalism WWIDocumento2 páginasBalkan Nationalism WWIdragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Balkan Nationalism WWIDocumento2 páginasBalkan Nationalism WWIdragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Rezumat Pedestrians DriversDocumento3 páginasRezumat Pedestrians Driversdragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- McFARLANE - Regional Organizations and Regional SecurityDocumento33 páginasMcFARLANE - Regional Organizations and Regional Securitydragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Rezumat Pedestrians DriversDocumento3 páginasRezumat Pedestrians Driversdragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Engleza 1Documento2 páginasEngleza 1dragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Nationalism As An Important Element of International RelationsDocumento33 páginasNationalism As An Important Element of International Relationsdragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- CHIPMAN - The Future of Strategic StudiesDocumento24 páginasCHIPMAN - The Future of Strategic Studiesdragan_andrei_1100% (1)

- AMITAV - The Emerging Regional Architecture of World Politics (Review Regions and Powers)Documento25 páginasAMITAV - The Emerging Regional Architecture of World Politics (Review Regions and Powers)dragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- AMITAV - The Emerging Regional Architecture of World Politics (Review Regions and Powers)Documento25 páginasAMITAV - The Emerging Regional Architecture of World Politics (Review Regions and Powers)dragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Links MicuDocumento1 páginaLinks Micudragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações

- DESCH - A Final Solution To A Recurrent TragedyDocumento17 páginasDESCH - A Final Solution To A Recurrent Tragedydragan_andrei_1Ainda não há avaliações