Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

PIRO Score For Community-Acquired Pneumonia - Articulo Cohorte

Enviado por

ChangTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

PIRO Score For Community-Acquired Pneumonia - Articulo Cohorte

Enviado por

ChangDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/23712126

PIRO score for community-acquired

pneumonia: A new prediction rule for

assessment of severity in intensive care unit

patients with community-acquired

pneumonia

ARTICLE in CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE JANUARY 2010

Impact Factor: 6.15 DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318194b021 Source: PubMed

CITATIONS DOWNLOADS VIEWS

62 980 202

6 AUTHORS, INCLUDING:

Jordi Rello Thiago Lisboa

VHIR Vall dHebron Research Institute Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul

275 PUBLICATIONS 8,061 CITATIONS 96 PUBLICATIONS 1,478 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Manel Lujn Richard G Wunderink

Corporaci Sanitria Parc Taul Northwestern University

46 PUBLICATIONS 640 CITATIONS 245 PUBLICATIONS 9,299 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Available from: Manel Lujn

Retrieved on: 17 June 2015

PIRO score for community-acquired pneumonia: A new prediction

rule for assessment of severity in intensive care unit patients with

community-acquired pneumonia*

Jordi Rello, MD, PhD; Alejandro Rodriguez, MD, PhD; Thiago Lisboa, MD; Miguel Gallego, MD;

Manel Lujan, MD; Richard Wunderink, MD, PhD

Objective: To develop a severity assessment tool to predict vivors than in survivors (4.6 1.2 vs. 2.3 1.4). Considering the

mortality in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) patients in observed mortality for each PIRO score, the patients were strat-

intensive care unit (ICU), comparing its performance with Acute ified in four levels of risk: a) Low, 0 2 points; b) Mild, 3 points; c)

Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score and high, 4 points; and d) Very high, 5 8 points. Mild-risk (hazard

American Thoracic Society/Infectious Disease Society of America ratio HR 1.8; 95% confidence interval CI 1.12.9; p < 0.05),

(ATS/IDSA) criteria as a prognostic index in CAP patients requiring high-risk (HR 3.1; 95% CI 2.0 4.7; p < 0.001), and very high

ICU admission. risk levels (HR 6.3; 95% CI 4.29.4; p < 0.001) were signifi-

Design: Secondary analysis of prospective observational co- cantly associated with higher risk of death in Cox proportional

hort study. hazards regression analysis. Furthermore, analysis of variance

Setting: Thirty-three ICUs. showed that higher levels of PIRO score were significantly asso-

Patients: Five hundred and twenty-nine adult patients with ciated with higher mortality (p < 0.001), prolonged length of stay

CAP requiring ICU admission. in the ICU (p < 0.001), and days of mechanical ventilation (p <

Measurements and Main Results: A severity assessment score 0.001). Receiver operating characteristic curves showed that PIRO

was developed based on the PIRO (predisposition, insult, re- score (area under the curve [AUC] 0.88) performed better than

sponse, and organ dysfunction) concept including the presence of APACHE II (AUC 0.75, p < 0.001) and ATS/IDSA criteria (AUC

the following variables: Comorbidities (chronic obstructive pul- 0.80, p < 0.001) to predict 28-day mortality.

monary disease, immunocompromise); age >70 years; multilobar Conclusions: The PIRO score performed well as 28-day mor-

opacities in chest radiograph; shock, severe hypoxemia; acute tality prediction tool in CAP patients requiring ICU admission with

renal failure; bacteremia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. a better performance than APACHE II and ATS/IDSA criteria in this

PIRO score was obtained at ICU within 24 hours from admission, subset of patients. Furthermore, PIRO score also is associated

and one point was given for each present feature (range, 0 8 with increased healthcare resource utilization in CAP patients

points). The mean PIRO score was significantly higher in nonsur- admitted in the ICU. (Crit Care Med 2009; 37:456 462)

T he pneumonia severity index department. Patients in class V (130 ence sponsored by Society of Critical Care

(PSI) was designed to classify points) have the highest severity, with an Medicine, European Society of Intensive

patients with community-ac- estimated mortality of 27%. This is a het- Care Medicine, American College of

quired pneumonia (CAP) to erogeneous group of patients with a wide Chest Physicians, ATS, and Surgical In-

guide home discharge at the emergency range of severity, and 2 of 3 remain out of fection Society and provided the basis for

the intensive care unit (ICU) (1). The Amer- introducing PIRO as a hypothesis-gener-

ican Thoracic Society (ATS)-revised criteria ating model for future research (6). It was

*See also p. 744. (2) and the CURB-65 (confusion, urea, re- inspired in the TNM system (7), which

From the Critical Care Department (JR, AR, TL), spiratory rate, blood pressure, and age 65 classifies malignant tumor grade, and

Joan XXIII University Hospital, University Rovira and

Virgili, Institut Pere Virgili, CIBER Enfermedades Res- years) score (3) are better to assist decisions was developed to denote the extent of

piratorias, Tarragona, Spain; Pneumology Department regarding site of care. Unfortunately none pathologic involvement, stratify thera-

(MG, ML), Corporacio Sanitaria Parc Taul, Sabadell, of the scores stratify patients with high peutic approaches, and predict outcome.

Spain; and Pulmonary and Critical Care Division (RW), severity. A score identifying different levels The elements of the PIRO concept (6) are

Northwestern University Hospital, Chicago, IL.

Supported, in part, by 06/06/36 from Fondo de

of risk would be useful to improve decision predisposition (chronic illness, age, and

Investigaciones Sanitarias (CIBERes Enfermedades making in terms of the most appropriate comorbidities); insult (injury, bactere-

Respiratorias) and by 2005/SGR/920 from AGAUR. treatment site, comparison in clinical tri- mia, endotoxin); response (neutropenia,

The authors has not disclosed any potential con- als, and better define criteria to indicate hypoxemia, hypotension); and organ dys-

flicts of interest.

For information regarding this article, E-mail:

adjuvant therapies. The use of biologi- function.

jordi.rello@urv.cat or jrello.hj23.ics@gencat.net cal (4) or physiologic (5) markers re- In this article, we hypothesize that

Copyright 2009 by the Society of Critical Care mains premature. improvements in the management of

Medicine and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins In 2003, an international panel of ex- ICU patients with severe CAP (SCAP)

DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318194b021 perts participated in a consensus confer- may follow the development of a stag-

456 Crit Care Med 2009 Vol. 37, No. 2

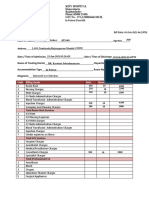

Table 1. Variables included in PIRO score for community-acquired pneumonia evidence of pneumonia as primary diagnosis,

confirmed by chest radiograph and clinical

Score Variables Point findings. The study focused on patients in the

ICU and excluded patients with respiratory

Predisposition Comorbidities (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or 1

infection other than pneumonia (e.g., exacer-

immunocompromise)

70 yrs 1 bation of chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-

Insult Bacteremia 1 ease). A wide range of demographic, clinical,

Multilobar opacities in chest radiograph 1 and laboratory measures were recorded in

Response Shock 1.1 each patient, as described elsewhere (10).

Severe hypoxemia Patients were observed until death or ICU

Organ dysfunction Acute renal failure acute respiratory distress syndrome 1.1

Score range 08 discharges. Following Food and Drug Admin-

istration recommendations for clinical trials,

PIRO, predisposition, insult, response, and organ dysfunction. 28-day survival was chosen as primary end-

point. Patients discharged from the ICU before

90 28 days were considered as survivors.

The CAPUCI database was used to develop

80 76.6

the severity assessment model based on the

PIRO concept (6). The variables used in the

70

new score (chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-

60 56.1 ease, immunocompromise, multilobar opaci-

Mortality rate (%)

ties in chest radiograph, shock, severe hypox-

50 emia, and acute renal failure) were selected

from the current literature as the more signif-

40 34.4 icant in CAP prognosis (10 12) or because

30 25 they were considered with clinical importance

(bacteremia and acute respiratory distress syn-

20 17.1

12.6

drome). A clinical predictor rule (PIRO score

7.8 for CAP) was subsequently calculated at ICU

10

within 24 hours from admission, and one

0 point was given for each feature that was

0 to 5 6 to 10 11 to 15 16 to 20 21 to 25 26 to 30 more 31 present (range, 0 8 points) (Table 1). In ad-

dition, the severity of illness was assessed by

APACHE II Score (points) APACHE II (8) and by 2007 ATS/IDSA criteria

Figure 1. Twenty-eight-day mortality rate according Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (9) for each patient at ICU admission.

(APACHE) II score in 529 patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Definitions. CAP was defined as an acute

lower respiratory tract infection characterized

by a) an acute pulmonary infiltrate evident on

Table 2. Incidence and associated mortality with Our objectives were to develop an as- chest radiographs and consistent with pneu-

PIRO score variables sessment tool to enable the stratification monia; b) confirmatory findings on clinical

of critically ill patients with CAP into examination; and c) acquisition of the infec-

Incidence Mortality

Variables n (%) OR Univariate mortality risk groups to compare the per- tion outside a hospital, long-term care facility,

formance of the PIRO score with the or nursing home (10).

Comorbidities 258 (48.8) 1.9 (1.32.8) Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Immunocompromise was defined as pri-

70 yrs 163 (30.8) 1.9 (1.32.9) mary immunodeficiency or immunodeficiency

Bacteremia 89 (16.8) 1.8 (1.12.8) Evaluation (APACHE) II score (8) and

secondary to radiation treatment, use of cyto-

Multilobar 250 (47.3) 4.2 (2.76.3) 2007 ATS/IDSA criteria (9) as a prognos-

opacities in toxic drugs or steroids (daily doses 20 mg of

tic index in ICU patients admitted with prednisolone or the equivalent for 2 weeks,

chest radiograph

Shock 270 (51.0) 12.4 (7.321.2) CAP and to evaluate prediction of PIRO or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or

Severe hypoxemia 349 (66.0) 19.9 (8.646.1) score for healthcare resources utilization. malignancy (10). Multilobar compromise in

Acute renal failure 178 (33.6) 12.6 (8.119.8)

Acute respiratory 23 (4.3) 70.1 (9.91408.9)

chest radiograph was considered when more

distress METHODS than single lobe opacities were observed in

syndrome chest radiograph. Shock was defined as the

This is a historical cohort study including need for vasopressors for 4 hours after ade-

PIRO, predisposition, insult, response, and or- all patients with CAP requiring ICU admission quate fluid replacement (10, 12); Severe hy-

gan dysfunction. prospectively recorded in the CAPUCI Data- poxemia was defined as the PaO2/FIO2 ratio

base (10). Details of this study have been pre- 300 requiring mechanical ventilation (either

sented elsewhere (10 12). Briefly, 529 consec- invasive or noninvasive). Acute renal failure

ing system inspired in the PIRO con- utive patients with SCAP admitted in the ICU was defined as an urine output of 20 mL/hr

cept, which can better characterize the in 33 hospitals in Spain were enrolled. Insti- or a total urine output of 80 mL in 4 hours.

syndrome on the basis of predisposing tutional review board approval was obtained in Details of other definitions have been reported

factors and premorbid conditions, the accordance with local requirements, and in- elsewhere (5, 10 12).

nature of the underlying affection, the formed consent was waived because of the The 2007 ATS/IDSA criteria (9) were de-

characteristics of the host response, observational nature of the study. fined based on the presence of major criteria.

and the extend of the resultant organ The patients enrolled were consecutive pa- Major criteria are defined as requirement of

dysfunction. tients with age 18 years, with conclusive mechanical ventilation and presence of septic

Crit Care Med 2009 Vol. 37, No. 2 457

Table 3. Distribution of PIRO, Acute Physiology, and Chronic Health Evaluation II score and calculated in all patients. By convention, ac-

ATS/IDSA criteria in different subset of patients cording to the mortality rate observed, pa-

tients were classified into four levels of sever-

Acute Physiology ity: low, mild, high, and very high risk.

and Chronic Health The patients were stratified by PIRO score,

PIRO Score Evaluation II Score ATS/IDSA Major Criteria and ATS/IDSA major criteria presence and

survival curves were compared using Cox Pro-

Variable (n) Mean SD Mean SD 0 1 2 portional Hazards regression.

The operative indices (sensitivity, specific-

Survivors ity, positive, and negative predictive values) of

Yes 381 2.3 1.4 17.6 6.5 144 (97.3) 129 (87.8) 108 (46.2)

PIRO score were determined for different cut-

No 148 4.6 1.2a 23.6 6.6a 4 (2.7) 18 (12.2) 126 (53.8)a

Bacteremia off point, and the positive Likelihood ratio was

Yes 90 4.3 1.5 21.8 6.5 20 (13.5) 17 (11.6) 52 (22.2) calculated.

No 439 2.7 1.6a 18.7 7.0a 128 (86.5) 130 (88.4) 182 (78.8)a The discriminative power of APACHE II

Chronic obstructive score, ATS/IDSA criteria, and PIRO score for

pulmonary Disease CAP were assessed through measuring and

Yes 196 3.6 1.6 21.0 7.0 48 (32.4) 53 (36.1) 95 (40.6) pairwise comparing the area under the re-

No 333 2.6 1.6a 18.3 6.8a 100 (67.6) 94 (63.9) 139 (59.4) ceiver operating characteristic (ROC). The

Immunocompromise ROC curve was plotted for each score using

Yes 70 3.7 1.5 20.4 6.3 14 (9.5) 20 (13.6) 36 (15.4) sensitivity and specificity values for true pre-

No 459 2.8 1.7a 19.8 7.1 134 (90.5) 127 (86.4) 198 (84.6)

diction of ICU mortality across the whole

Age mt 70 yrs

Yes 163 3.9 1.6 22.2 6.1 39 (26.3) 45 (30.6) 79 (33.8) range of possible cut-off of predictive mortal-

No 366 2.5 1.6a 17.9 7.0a 109 (73.7) 102 (69.4) 155 (66.2) ity. The area under ROC (AUROC) curve was

Multilobar compromise considered a composite index of discrimina-

Yes 250 3.8 1.5 20.2 7.1 39 (26.3) 52 (35.3) 159 (67.9) tion (13). As AUROC approaches 1.0, the

No 279 2.1 1.4a 18.4 6.9a 109 (73.7) 95 (64.7) 75 (32.1)a model becomes more perfect; as the perfor-

Shock mance of the model become more random, the

Yes 270 4.1 1.3 21.6 7.1 0 (0) 38 (25.8) 234 (100) AUROC trends toward 0.5. All results were

No 259 1.7 1.1a 16.7 6.0a 148 (100) 109 (74.2) 0 (0)a tested against APACHE II score and ATS/IDSA

Severe hypoxemia

criteria. The results are expressed as odds ra-

Yes 349 3.7 1.4 20.7 7.1 5 (3.4) 111 (75.5) 234 (100)

No 180 1.4 1.1a 16.3 5.9a 143 (96.6) 36 (24.5) 0 (0)a tios and p values with 95% confidence inter-

Acute renal failure vals (CIs) and using ROC to plot sensitivity

Yes 178 4.5 1.2 23.0 6.5 12 (8.1) 29 (19.7) 137 (58.5) against specificity. The area under the curve,

No 351 2.1 1.3a 17.3 6.5a 136 (91.9) 118 (80.3) 97 (41.5)a standard error, and 95% CI are given and

Acute respiratory values were compared using the Students t

distress syndrome test. The chi-square test was used to compare

Yes 23 4.5 1.5 22.6 6.1 3 (2.0) 5 (3.4) 15 (6.4) proportions. The significance level of all anal-

No 506 2.9 1.7 19.1 7.0a 145 (98.0) 142 (96.6) 219 (93.6) ysis was defined as p 0.05.

ATS/IDSA, American Thoracic Society/Infectious Disease Society of America; PIRO, predisposition,

insult, response, and organ dysfunction. RESULTS

a

p 0.01.

The baseline characteristics of pa-

100 tients who did and did not survive to ICU

5 13 Alive have been reported elsewhere (10 12).

90 3 Dead The mean of APACHE II score at ICU

80

40

admission for all patients was 18.8 7.4,

Number of patients

70 being higher (p 0.01) in nonsurvivors

60 than survivors (22.9 7.6 vs. 17.4 6.8,

50 53 respectively). When the patients were dis-

91 87

86

40 0

tributed according to the APACHE II

30 scoring, the mortality rate increased sig-

53

20 37

nificantly (p 0.001) (Fig. 1).

26

10 22 Distribution and association with

5 8 mortality for each variable considered in

0 0

PIRO score are detailed in Table 2. Details

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 on distribution of the variables consid-

PIRO Score (points) ered for the PIRO score according to

Figure 2. Distribution of 529 patients according predisposition, insult, response, and organ dysfunc- APACHE II and ATS/IDSA major criteria

tion (PIRO) score and intensive care unit outcome. are shown in Table 3. When using ATS/

IDSA criteria, mortality decreased from

shock. Patients were classified as having 0, 1, The association between the PIRO score for 53% for patients with two major criteria,

or 2 major ATS/IDSA criteria. CAP and mortality was first assessed by strat- 12% with only one major criteria, and

Statistical Analysis. Data were analyzed ifying patients according to different levels of only 2.7% for patients admitted to the

using SPSS version 11.0 for windows (Chi- PIRO score and later into distinct risk groups. ICU with absence of major criteria. Dis-

cago, IL). Risk classes according to the PIRO score was tribution of 529 patients (survivors and

458 Crit Care Med 2009 Vol. 37, No. 2

100

100.0 shown). Presence of ATS/IDSA criteria

was also tested with Cox proportional re-

90 83.9

gression analysis, and the presence of 1

80

70.7 or 2 criteria was associated with higher

70 mortality (p 0.05) (Fig. 5). Finally,

Mortality rate (%)

60 discrimination of PIRO score for CAP was

p<0.001

50 43.0 assessed using ROC curves. The area un-

40 der ROC curve (Fig. 6) showed consistent

30 mortality discrimination by PIRO score

20

(0.88, 95% CI 0.83 0.9), with a better

13.0

performance than APACHE II score (0.75,

10 3.4 5.2

0.0 95% CI 0.70 0.80) and with a significant

0

difference between areas (p 0.001).

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ATS/IDSA major criteria presence (area

under the curve 0.80, 95% CI 0.77

PIRO Score (points)

0.84) also shows significant difference be-

Figure 3. Twenty-eight-day mortality rate according predisposition, insult, response, and organ tween the areas (p 0.001).

dysfunction (PIRO) score for community-acquired pneumonia.

In survivors, medical resources utili-

zation (Table 7), evaluated using length

of stay in the ICU and mechanical venti-

nonsurvivors) according with PIRO score jor criteria are shown in Table 4. Table 5 lation days, increased significantly ac-

for CAP are shown in Figure 2. The mean shows predictive values for different cut- cording to level of risk defined by the

PIRO score for all patients was 2.9 1.7, off points of PIRO score. A PIRO score PIRO score (Fig. 7).

being significantly higher (p 0.001) in cut-off 4 points was associated with the

nonsurvivors than survivors (4.6 1.2 best performance to predict death with a DISCUSSION

vs. 2.3 1.4, respectively). When the sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 76%.

patients were distributed according PIRO Considering the observed mortality for This is the first study designed to assess

scoring, the mortality rate increased sig- each PIRO score (Fig. 3), the patients were the usefulness of a score inspired in the

nificantly (p 0.001) (Fig. 3). There was stratified in four levels of risk: a) Low, 0 2 PIRO concept to stratify critically ill pa-

no difference in PIRO score between early points; b) Mild, 3 points; c) high, 4 points; tients with CAP. Our findings support that

or late ICU mortality in SCAP patients. and d) Very high, 5 8 points. In the uni- this score, based on the PIRO concept (6,

Distribution and mortality of patients ac- variate analysis (Table 6) the mild, high, 14 17), is feasible for stratification of se-

cording to the presence of ATS/IDSA ma- and very high risk levels were associated verity and improved prediction of 28-days

with significantly higher risk of death. mortality when compared with the

The effect of each PIRO risk levels was APACHE II score (8) and the 2007 ATS/

Table 4. Mortality according to presence of ATS/ tested with the Cox proportional hazards IDSA criteria (9) for CAP severity. Further-

IDSA major criteria more, it was useful to predict healthcare

regression analysis, and it showed that

mild (hazard ratio 1.8; 95% CI 1.12.9; utilization (length of stay in the ICU and

Risk According

ATS/IDSA Criteria n (%) Death (%) p 0.05), high (hazard ratio 3.1; 95% CI requirement of mechanical ventilation).

2.0 4.7; p 0.001), and very high risk The PIRO concept (6, 14 17) has

Absence of major 148 (28.0) 4 (2.7) level (hazard ratio 6.3; 95% CI 4.29.4; arisen as a classification scheme for sep-

criteria p 0.001) were significantly associated sis that considers the predisposing con-

One major criteria 147 (27.8) 18 (12.2)

with higher risk of death (Fig. 4). This ditions, the nature and extent of insult,

Two major criteria 234 (44.2) 126 (53.8) the nature and magnitude of the host

association remained significant when

the model was adjusted by the severity of response, and the degree of concomitant

ATS/IDSA, American Thoracic Society/Infec-

organ dysfunction. Our score was build

tious Disease Society of America. illness (APACHE II score) (data no

based in this concept and has included

variables significantly associated with

Table 5. Test characteristics of PIRO score for mortality in 529 patients hospitalized with severe mortality in univariate analysis in our

community-acquired pneumonia database of SCAP patients admitted to

ICU. These parameters selected were

Positive Negative Positive based on prior evidence supporting its

PIRO Score Sensitivity Specificity Predictive Predictive Likelihood association with poor prognosis and fit

(n 529) (%) (%) Value (%) Value (%) Ratio

with the PIRO definitions.

mt 1 100 10 30 100 1.1 A potential strength of our study is the

2 98 32 36 98 1.4 simplicity of the PIRO score. It is based

3 95 56 46 96 2.1 on easily available variables, all with

4 86 79 61 93 4.0 known impact in the CAP mortality. It

5 59 93 76 85 8.3

allows an easy risk stratification of pa-

6 23 99 87 77 17.5

7 5 100 100 73 NA tients in different levels of severity with

progressive rates of mortality. Further-

PIRO, predisposition, insult, response, and organ dysfunction. more, it is also associated with progres-

Crit Care Med 2009 Vol. 37, No. 2 459

Table 6. Univariate analysis for mortality of different PIRO score level of risk sive increment in medical resources uti-

lization in ICU. Optimize therapy based

Univariate Analysis

on this classification is a strategy that

Risk According PIRO Score n (%) Death (%) OR (95%CI) should be evaluated, as patients at higher

risk might benefit from more aggressive

Low risk (02 points) 222 (42.0) 8 (3.6) 1 strategies or adjuvant therapy (e.g., cor-

Mild risk (3 points) 100 (18.9) 13 (13.0) 4.0 (1.610.0) ticosteroids).

High risk (4 points) 93 (17.6) 40 (43.0) 20.2 (8.945.7) The use of scores to evaluate CAP se-

Very high risk (58 points) 114 (21.5) 87 (76.3) 86.2 (37.7197.0)

verity is a useful strategy to identify sub-

sets of patients likely to need more com-

plex local healthcare setting. The

majority of studies assessing severity in

1,0 CAP patients are done in emergency set-

LOW ting. The PSI was described by Fine et al

(18) and aimed to identify patients who

MILD could be discharged home with safety. It

0,8

overestimates age and can underestimate

severity, particularly in patients without

Cumulative survival

HIGH

comorbidities. There is no validation

0,6 study evaluating the impact of the need of

ICU based on PSI index. Recently, Valen-

cia et al (1) showed that only 20% of PSI

VERY HIGH

class V patients are admitted to the ICU,

0,4 which shows that many patients classified

as severe based in this score may be not

so severe. The CURB-65 score based on

0,2

confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood

pressure, and age and its variations are

easier to use and predict mortality well

(3, 20 22). However, this score per-

0,0 formed poorly when needed for ICU ad-

mission was the endpoint (23).

0 4 8 12 16 20 24 28 Our results also show that presence of

Days major ATS/IDSA criteria (9) was associ-

ated with higher mortality. Several stud-

Figure 4. Survival graph (Cox analysis) for 529 patients stratified by predisposition, insult, response,

and organ dysfunction score (censored at 28 days).

ies have already evaluated these criteria

but never in a subset of ICU patients.

However, a more detailed evaluation tool

such as PIRO-based score may add useful

1,0 0 major criteria

information and allow a more accurate

1 major criteria

prediction in this group of patients. The

APACHE II (8) is not a specific score to

0,8 evaluate severity in CAP patients. How-

ever, Kollef et al (24) evaluated APACHE

II accuracy to predict mortality in pa-

Cumulative Survival

0,6 tients with methicilin-resistant Staphylo-

2 major criteria

coccus aureus pneumonia and found that

APACHE II score has better accuracy

0,4

when compared with CURB-65 and CRB-

65. This difference was present in com-

munity-acquired methicilin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia and

0,2

health care-associated methicilin-resis-

tant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia,

demonstrating the utility of this tool to

0,0 predict mortality in this subset of pa-

tients. Furthermore, APACHE II is the

0 4 8 12 16 20 24 28

most widely employed score to evaluate

Days risk of death in intensive care and has

Figure 5. Survival graph (Cox analysis) for 529 patients stratified by presence of American Thoracic been validated in different subsets of pa-

Society/Infectious Disease Society of America major criteria (censored at 28 days). tients (2527).

460 Crit Care Med 2009 Vol. 37, No. 2

1,0 patients. Identifying the subset of critically

ill patients with SCAP likely to have adverse

PIRO Score APACHE II Score

outcomes seems to be a key step in reduc-

0,8 ing morbidity and mortality.

Our study has several limitations. Al-

though all selected variables were signif-

icantly associated with mortality, they

Sensitivity

0,6

were selected arbitrarily. Furthermore,

the same weight (presence/absence) was

adjudicated for each variable, although

0,4

ATS/IDSA odds ratios in univariate analysis were

Criteria

different, to enhance simplicity. Under

these conditions, PIRO score performed

0,2 very well and predicted 28-day mortality

in ICU patients, which is better than

other available tools, such as APACHE II

0,0 (8) and ATS/IDSA criteria (9). Indeed, a

0,0 0,2 0,4 0,6 0,8 1,0 clinically useful set of criteria for evalu-

1- Specificity ating infected patients will necessarily be

Figure 6. Receiver operating characteristic curves comparing predisposition, insult, response, and organ somewhat arbitrary. It must be judged

dysfunction (PIRO) score, American Thoracic Society/Infections Disease Society of America (ATS/IDSA) successful if clinicians regard them as an

criteria, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II to predict 28-day mortality. aid for decision making at the bedside (6).

Further studies should validate PIRO

Table 7. Healthcare resource utilization in survivors, according to risk levels, defined by PIRO score score in populations with different de-

grees of severity and for hospital mortal-

Intensive Care Unit Length of Stay Mechanical Ventilation Days ity and 90-day mortality rates. Whether

our findings may be extrapolated to pa-

Level of Risk Median Median

PIRO Score Mean (SD) (Interquartile Range) Mean (SD) (Interquartile Range)

tients out of the ICU (e.g., emergency

department) is unknown. Unfortunately,

Low 10.3 (9.0) 7 (413) 4.0 (7.0) 1.0 (05) we were not able to establish compari-

Mild 19.4 (15.4)a 15 (827) 12.4 (13.5)a 8 (217) sons with PSI (18) or CURB (19) or

High 22.1 (21.0)a 14 (629) 16.5 (20.4)a 10 (423) APACHE IV scores (28) as we do not have

Very high 26.0 (23.8)a 22 (929) 17.8 (19.0)a 10 (522)

these data collected. However, an original

PIRO, predisposition, insult, response, and organ dysfunction. aspect of our study was to evaluate SCAP

a

p 0.05 (analysis of variance). patients admitted to ICU, although PSI

Interquartile range 2575. (18) and CURB score (19) have not been

adequately validated in this population.

Days MV LOS ICU Another potential limitation is the ab-

28 26 sence of protocolized criteria for ICU ad-

mission between different institutions.

22.1

This is because of the absence of gold

21 19.4

17.8 standard or definitive criteria to define

p<0.001 16.5

ICU admission (1). These decisions are

Days

14 12.8 12.4 mainly based on clinical judgment, and

8.9 its variability may limit the potential gen-

7.3

7 5.9 eralization of our findings. Further stud-

3.3 ies should clarify this issue.

1.3

In conclusion, we developed a severity

0

assessment score for CAP patients based on

0 1 2 3 4 >5 the PIRO concept (6, 14 17), which ade-

PIRO score quately predicted 28-day mortality in CAP

Figure 7. Length of stay (LOS) in intensive care unit (ICU) and mechanical ventilation (MV) days on patients admitted to ICU. Furthermore, be-

survivors according to predisposition, insult, response, and organ dysfunction (PIRO) score. ing associated with increment in medical

resources utilization in ICU, it performed

better than the APACHE II score (8) and

A very conflicting issue in CAP is def- vere community-acquired pneumonia pa- ATS/IDSA criteria (9) to identify patients

inition of SCAP. None of the scores till tients in the emergency department. How- with higher risk of death. Its simplicity may

date has focused on SCAP patients admitted ever, in this study, only 4% of patients were help to stratify patients with PSI above 130

to ICU. The available CAP severity assess- admitted to ICU, and in-hospital mortality (class V) in different categories of severity,

ment scores do not include ICU patients was less than 10%. All our patients were being useful for pharmacoeconomic or out-

significantly. Espana et al (20) describe a admitted in the ICU, and overall mortality come comparisons, and to select candidates

clinical prediction rule for identifying se- was 28%, a much more severe subset of for adjunctive therapy in clinical trials.

Crit Care Med 2009 Vol. 37, No. 2 461

REFERENCES 10. Bodi M, Rodrguez A, Sole-Violan J, et al: Development and validation of a clinical pre-

Antibiotic prescription for community- diction rule for severe community-acquired

1. Valencia M, Badia JR, Cavalcanti M, et al: acquired pneumonia in the intensive care pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;

Pneumonia severity index class V patients unit: Impact of adherence to Infectious Dis- 174:1249 1256

with community-acquired pneumonia: Char- ease Society of America guidelines on sur- 21. Angus DC, Marrie TJ, Obrosky DS, et al:

acteristics, outcomes and value of severity vival. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1709 1716 Severe community-acquired pneumonia: Use

scores. Chest 2007; 132:515522 11. Rello J, Rodrguez A, Torres A, et al: Impli- of intensive care services and evaluation of

2. Ewig S, Ruiz M, Mensa J, et al: Severe com- cations of COPD in patients admitted to the American and British Thoracic Society diag-

munity-acquired pneumonia: Assessment of intensive care unit by community-acquired nostic criteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

severity criteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006; 27: 2002; 166:717723

1998; 158:11021108 1210 1216 22. Bauer TT, Ewig S, Marrie R, et al; the CAP-

3. Lim WS, van del Eerden MM, Laing R, et al: 12. Rodrguez A, Mendia A, Sirvent J-M, et al: NETZ Study Group: CRB-65 predicts death

Defining community acquired pneumonia Combination antibiotic therapy improves from community-acquired pneumonia. J Int

severity on presentation to hospital: An in- survival in patients with community-ac- Med 2006; 260:93101

ternational derivation and validation study. quired pneumonia and shock. Crit Care Med 23. Feldman C: Prognostic scoring system:

Thorax 2003; 58:377378 2007; 35:14931498 Which one is best? Curr Opin Infect Dis

4. Rello J, Rodrguez A: Severity of illness as- 13. Hanley J, McNeil B: The meaning and the use 2007; 20:165169

sessment for managing community-acquired of the area under a receiver operating char- 24. Kollef KE, Reichley RM, Micek ST, et al: The

pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2007; 33: acteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982; 143: modified APACHE II score outperforms

20432044 29 36 CURB65 pneumonia severity score as a pre-

5. Blot S, Rodrguez A, Sole-Violan J, et al: 14. Angus DC, Burgner D, Wunderink R, et al: dictor of thirty-day mortality on methicillin-

Effects of delayed oxygenation assessment on The PIRO concept: P is for predisposition. resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia.

time to antibiotic delivery and mortality in Crit Care 2003; 7:248 251 Chest 2007; In Press

patients with severe community-acquired 15. Vincent JL, Opal S, Torres A, et al: The PIRO 25. Kaya E, Dervisoglu A, Polat C: Evaluation of

pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: concept: I is for infection. Crit Care 2003; diagnostic findings and scoring systems in

2509 2514 7:252255 outcome prediction in acute pancreatitis.

6. Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al: 2001 16. Gerlach H, Dhainaut JF, Harbarth S, et al: World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13:3090 3094

SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International The PIRO concept: R is for response. Crit 26. Niskanen M, Kari A, Nikki P, et al: Acute

sepsis definitions conference. Crit Care Med Care 2003; 7:256 259 physiology and chronic health evaluation

2003; 31:1250 1256 17. Vincent JL, Wendon J, Groeneveld J, et al: APACHE II Score and Glasgow coma score as

7. Denoix PX: Enquete permanent dans les cen- The PIRO concept: O is for organ dysfunc- predictors outcome from intensive care after

tres anticancereaux. Bull Inst Natl Hyg 1946; tion. Crit Care 2003; 7:260 264 cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med 1991; 19:

1:70 75 18. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al: A predic- 14651473

8. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al: tion rule to identify low-risk patients with 27. Grmec S, Gasparovic V: Comparison of

APACHE II: A severity of disease classifica- community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl APACHE II, MEES and Glasgow Coma

tion system. Crit Care med 1985; 13: J Med 1997; 336:243250 Scale in patients with nontraumatic coma

818 829 19. British Thoracic Society and the Public for prediction of mortality Crit Care 2001;

9. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzuetto A, et Health Laboratory Service: Community- 5:19 23

al: Infectious Disease Society of America/ acquired pneumonia in adults in British hos- 28. Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, et

American Thoracic Society consensus guide- pitals in 19821983: A survey of aetiology, al: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health

lines on the management of community- mortality, prognostic factors and outcome. Q Evaluation (APACHE) IV: Hospital mortality

acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect J Med 19876; 239:195220 assessment for todays critically ill patients.

Dis 2007; 44(Suppl 2):S27S72 20. Espana PP, Capelastegui A, Gorordo I, et al: Crit Care Med 2006; 34:12971310

462 Crit Care Med 2009 Vol. 37, No. 2

Você também pode gostar

- Hydatidiform Mole - Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocumento22 páginasHydatidiform Mole - Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis - UpToDateChangAinda não há avaliações

- Practice Bulletin: Medical Management of Ectopic PregnancyDocumento7 páginasPractice Bulletin: Medical Management of Ectopic PregnancyChangAinda não há avaliações

- JCPDocumento11 páginasJCPChangAinda não há avaliações

- RCOG Guidelines - Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseDocumento12 páginasRCOG Guidelines - Gestational Trophoblastic Diseasemob3100% (1)

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease - Pathology - UpToDateDocumento18 páginasGestational Trophoblastic Disease - Pathology - UpToDateChangAinda não há avaliações

- RHEUMATOLOGY GUIDE FOR DISEASES AND TREATMENTSDocumento15 páginasRHEUMATOLOGY GUIDE FOR DISEASES AND TREATMENTSkeyurbAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of Couples With Recurrent Pregnancy Loss - UpToDateDocumento8 páginasEvaluation of Couples With Recurrent Pregnancy Loss - UpToDateChangAinda não há avaliações

- Hydatidiform Mole - Management - UpToDateDocumento15 páginasHydatidiform Mole - Management - UpToDateChangAinda não há avaliações

- Spontaneous Abortion - Risk Factors, Eti..., and Diagnostic Evaluation - UpToDateDocumento24 páginasSpontaneous Abortion - Risk Factors, Eti..., and Diagnostic Evaluation - UpToDateChangAinda não há avaliações

- Ectopic Pregnancy - Incidence, Risk Factors, and Pathology - UpToDateDocumento15 páginasEctopic Pregnancy - Incidence, Risk Factors, and Pathology - UpToDateChangAinda não há avaliações

- Practice Bulletin: Medical Management of Ectopic PregnancyDocumento7 páginasPractice Bulletin: Medical Management of Ectopic PregnancyChangAinda não há avaliações

- Preterm Birth - Risk Factors and Interventions For Risk Reduction - UpToDateDocumento35 páginasPreterm Birth - Risk Factors and Interventions For Risk Reduction - UpToDateChangAinda não há avaliações

- Tiki Taka CK EndocrinologyDocumento17 páginasTiki Taka CK EndocrinologykeyurbAinda não há avaliações

- TiKi TaKa CK Preventive MedicineDocumento3 páginasTiKi TaKa CK Preventive MedicinenonsAinda não há avaliações

- Hepatology Tiki TakaDocumento19 páginasHepatology Tiki TakaChangAinda não há avaliações

- TikiTaka StatisticsDocumento37 páginasTikiTaka StatisticsChangAinda não há avaliações

- Practice Bulletin No 171 Management of Preterm.61 PDFDocumento10 páginasPractice Bulletin No 171 Management of Preterm.61 PDFLoreGGuerreroAinda não há avaliações

- Tiki Taka Notes Final PDFDocumento104 páginasTiki Taka Notes Final PDFAditiSahak62Ainda não há avaliações

- Rafa Gastrica 1 PDFDocumento37 páginasRafa Gastrica 1 PDFChangAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing The Learning Environment of A Faculty - Articulo ValidacionDocumento14 páginasAssessing The Learning Environment of A Faculty - Articulo ValidacionChangAinda não há avaliações

- Corticosteroids For Managing Tuberculous Meningitis (Review)Documento4 páginasCorticosteroids For Managing Tuberculous Meningitis (Review)ChangAinda não há avaliações

- Sensitivity and Specificity of The Semiquantitative Latex Agglutination - Articulo Prueba DXDocumento5 páginasSensitivity and Specificity of The Semiquantitative Latex Agglutination - Articulo Prueba DXChangAinda não há avaliações

- Article PDFDocumento25 páginasArticle PDFChangAinda não há avaliações

- Efficacy and Safety of Paracetamol For Spinal Pain and Osteoarthritis Meta-Analysis - Articulo Revisión Sistemática PDFDocumento13 páginasEfficacy and Safety of Paracetamol For Spinal Pain and Osteoarthritis Meta-Analysis - Articulo Revisión Sistemática PDFChangAinda não há avaliações

- Criterios Diagnosticos y Grado de Severidad ColecistitisDocumento12 páginasCriterios Diagnosticos y Grado de Severidad ColecistitisYoub Luis Caro RojasAinda não há avaliações

- Production in Progress PDFDocumento1 páginaProduction in Progress PDFChangAinda não há avaliações

- Laboratory Diagnosis of Bacterial Gastroenteritis: Romney M. Humphries, Andrea J. LinscottDocumento29 páginasLaboratory Diagnosis of Bacterial Gastroenteritis: Romney M. Humphries, Andrea J. LinscottChangAinda não há avaliações

- Guarino 2014Documento21 páginasGuarino 2014ChangAinda não há avaliações

- TG13 Updated Tokyo Guidelines For The Management of AcuteDocumento7 páginasTG13 Updated Tokyo Guidelines For The Management of AcutechizonaAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Infection Control in ICU'sDocumento58 páginasInfection Control in ICU'stummalapalli venkateswara rao100% (1)

- Hospital Bill FormatDocumento2 páginasHospital Bill Formatsandee1910100% (1)

- Part One: Expressions (Items 1-15) Choose The Best Answer. Make-Up Class (1-3)Documento18 páginasPart One: Expressions (Items 1-15) Choose The Best Answer. Make-Up Class (1-3)หมิงฮวาAinda não há avaliações

- Hospital Case Study Max S.SDocumento8 páginasHospital Case Study Max S.SIqRa JaVedAinda não há avaliações

- ICU/CCU Only Competencies and Johns Hopkins MHA ICU ProjectDocumento107 páginasICU/CCU Only Competencies and Johns Hopkins MHA ICU Projecthery100% (2)

- Aplanando La CurvaDocumento6 páginasAplanando La CurvaJorge Alonso Pachas ParedesAinda não há avaliações

- Ballad Health Wise County Update Info SheetDocumento4 páginasBallad Health Wise County Update Info SheetAnonymous iBvi6lqXeUAinda não há avaliações

- Gordana Pavliša, Marina Labor, Hrvoje Puretić, Ana Hećimović, Marko Jakopović, Miroslav SamaržijaDocumento12 páginasGordana Pavliša, Marina Labor, Hrvoje Puretić, Ana Hećimović, Marko Jakopović, Miroslav SamaržijaAngelo GarinoAinda não há avaliações

- J Ijnurstu 2017 12 012Documento8 páginasJ Ijnurstu 2017 12 012Osborn KhasabuliAinda não há avaliações

- Use of Communication Tools For Mechanically Ventilated Patients in The Intensive Care UnitDocumento8 páginasUse of Communication Tools For Mechanically Ventilated Patients in The Intensive Care UnitCatalina CarreñoAinda não há avaliações

- Nurses' Knowledge and Practice Regarding Oral Care in Intubated Patients at Selected Teaching Hospitals, ChitwanDocumento8 páginasNurses' Knowledge and Practice Regarding Oral Care in Intubated Patients at Selected Teaching Hospitals, ChitwanAnonymous izrFWiQAinda não há avaliações

- McKenzie Aasfe 1st Place Division2Documento23 páginasMcKenzie Aasfe 1st Place Division2Margaret McKenzieAinda não há avaliações

- Peran Perawat Keperawatan KritisDocumento21 páginasPeran Perawat Keperawatan KritisRudi HariyonoAinda não há avaliações

- Anesthesia Analgesia September 2009Documento291 páginasAnesthesia Analgesia September 2009Alexandra PavloviciAinda não há avaliações

- Early Enteral NütritionDocumento9 páginasEarly Enteral NütritionSema NurAinda não há avaliações

- A P I C P C: A V U: Ospital Cquired Ressure Njuries in Ritical and Rogressive ARE Voidable Ersus NavoidableDocumento21 páginasA P I C P C: A V U: Ospital Cquired Ressure Njuries in Ritical and Rogressive ARE Voidable Ersus NavoidableDwi CahyoAinda não há avaliações

- 2020 Article 712Documento8 páginas2020 Article 712Agrinto TaloimAinda não há avaliações

- The Debate On The EThics of AI in Health Care Pre Print PDFDocumento35 páginasThe Debate On The EThics of AI in Health Care Pre Print PDFutkarsh kandpalAinda não há avaliações

- Nasal Cannula Vs Venturi MaskDocumento8 páginasNasal Cannula Vs Venturi MaskRoslitha HaryaniAinda não há avaliações

- SLEDDDocumento38 páginasSLEDDrini purwantiAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Care PDFDocumento509 páginasAcute Care PDFamatory1702Ainda não há avaliações

- Namachivayam 2012Documento9 páginasNamachivayam 2012dian rosmala lestariAinda não há avaliações

- NYCM Quill + Scope - Vol 3Documento102 páginasNYCM Quill + Scope - Vol 3burxardAinda não há avaliações

- Manpower Planning at Different LevelsDocumento13 páginasManpower Planning at Different Levelsdr_shilpa11Ainda não há avaliações

- Sedation and Analgesia in Critically Ill Neurologic PatientsDocumento24 páginasSedation and Analgesia in Critically Ill Neurologic PatientsrazaksoedAinda não há avaliações

- Ccs InfoDocumento13 páginasCcs Info786ss100% (1)

- Immediate Post Anesthetic RecoveryDocumento12 páginasImmediate Post Anesthetic Recoverysubvig100% (2)

- SMT ProfileDocumento12 páginasSMT ProfileTOHEEDAinda não há avaliações

- Guía Manejo Del Shock 2023Documento67 páginasGuía Manejo Del Shock 2023Alvaro ArriagadaAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation On Assessment of Patient in CCU: Presented byDocumento75 páginasPresentation On Assessment of Patient in CCU: Presented bySandhya HarbolaAinda não há avaliações